Submitted:

06 March 2024

Posted:

07 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

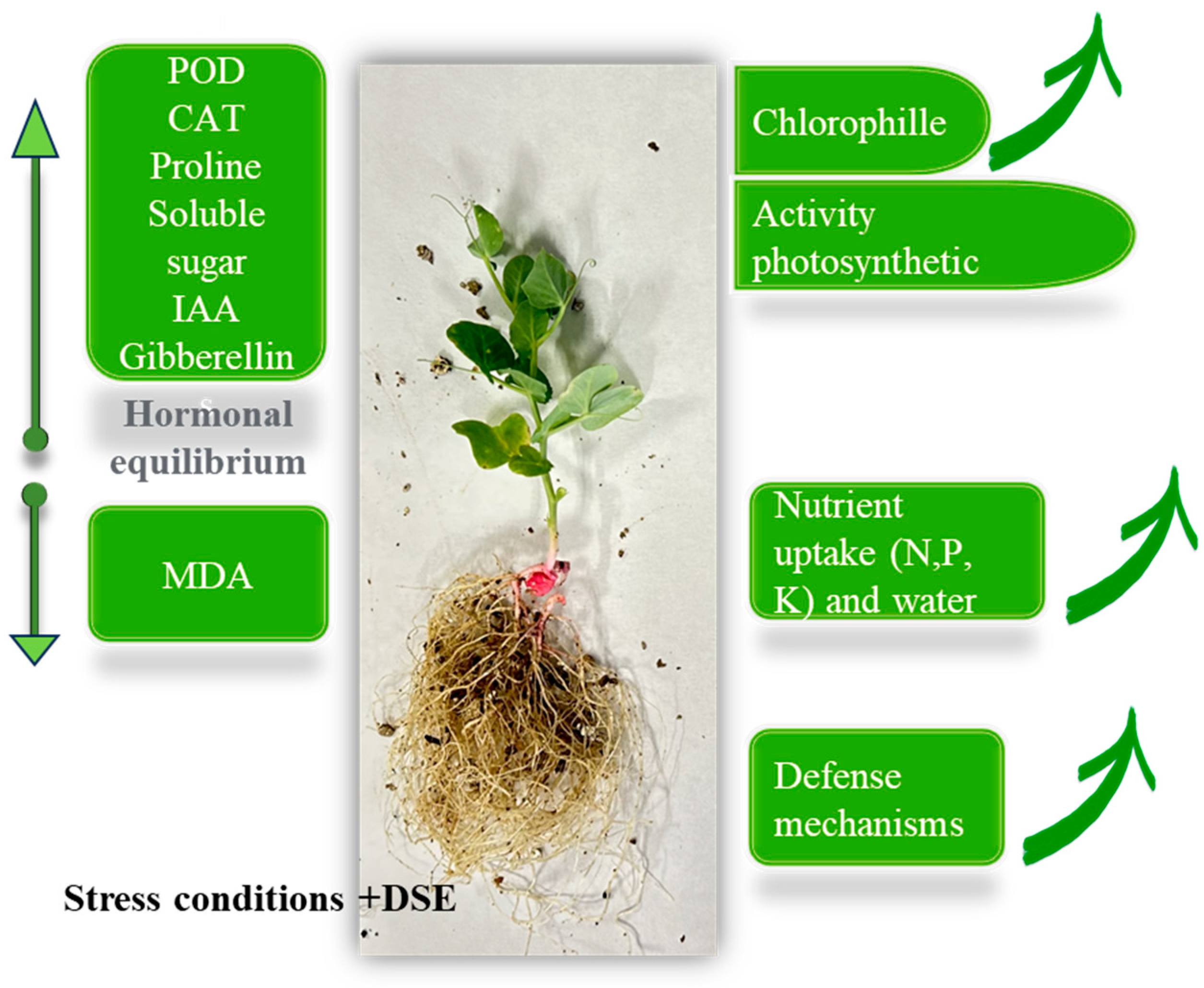

2. DSEs and Their Connection to Drought and Salinity Mitigation

3. Implication of DSEs in Fertilisation Reduction

4. Compatibility of DSEs with Other Microorganisms

5. Compatibility of DSEs with Active Chemical Substances

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mukherjee, S.; Mishra, A.; Trenberth, K.E. Climate change and drought: A perspective on drought indices. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2018, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, C.; Sevanto, S.; Patterson, A.; Ulrich, D. E. M.; Kuske, C.R. Ectomycorrhizal and dark septate fungal associations of pinyon pine are differentially affected by experimental drought and warming. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 582574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ramos, I.; Álvarez-Méndez, A.; Wald, K.; Matías, L.; Hidalgo-Galvez, M. D.; Fernández, C.M. Direct and indirect effects of global change on mycorrhizal associations of savanna plant communities. Oikos 2021, 130, 1370–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

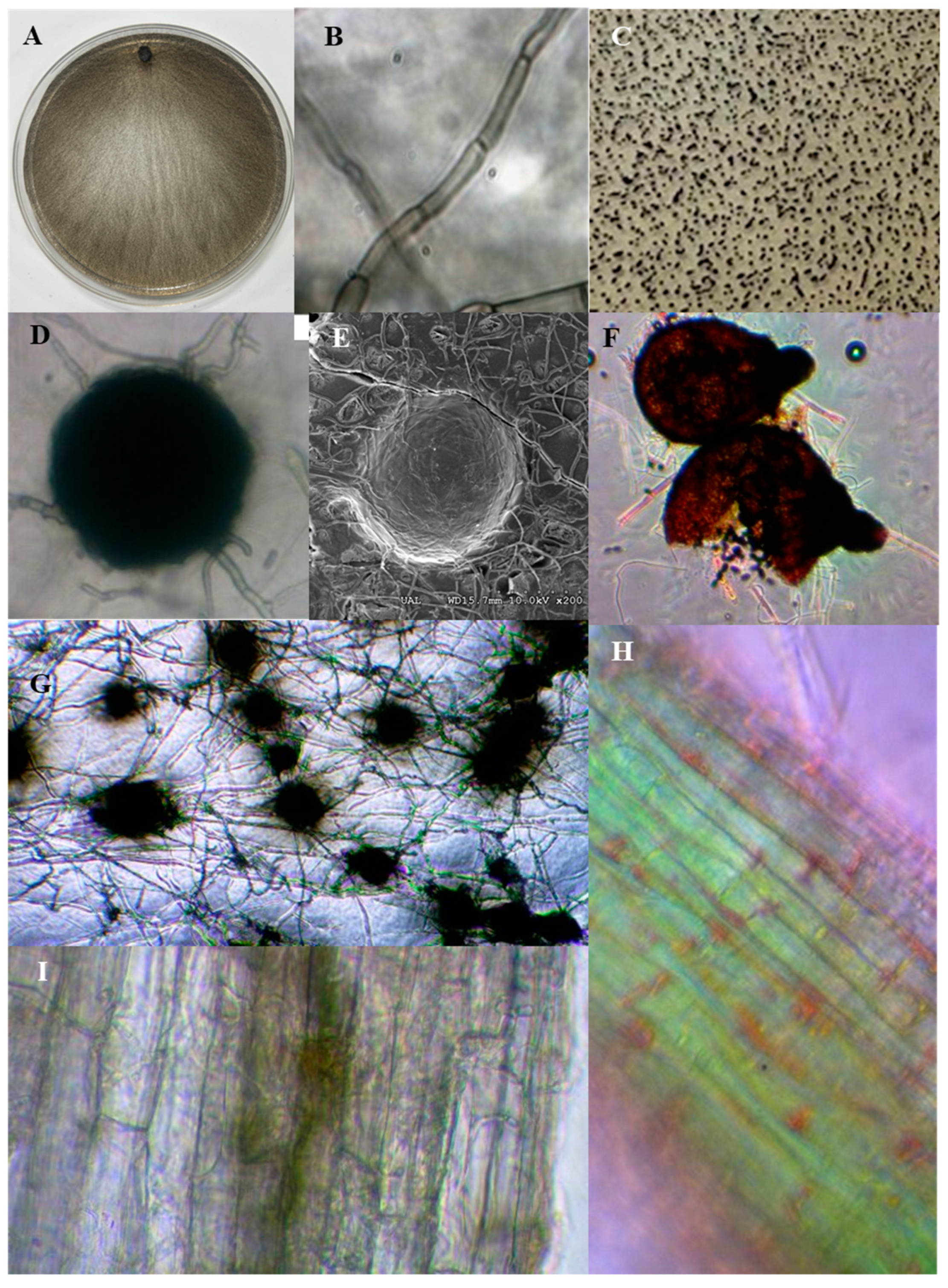

- Santos, M.; Cesanelli, I.; Diánez, F.; Sánchez-Montesinos, B.; Moreno-Gavira, A. Advances in the role of dark septate endophytes in the plant resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, X.L.; Zhou, Y.; Hou, Y.T.; Zuo, Y.L. Effects of dark septate endophytes on the performance of Hedysarum scoparium under water deficit stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolt, M.; Stroheker, S.; Queloz, V.; Gall, A.; Sieber, T.N. Does water availability influence the abundance of species of the Phialocephala fortinii s.l.-Acephala applanata complex (PAC) in roots of pubescent oak (Quercus pubescens) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris)? Fungal Ecol. 2020, 44, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gong, M.; Yuan, J.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Hou, X. Dark septate endophyte improves drought tolerance in sorghum. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2017, 19, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Li, X.; He, X. Effect of dark septate endophytes on plant performance of Artemisia ordosica and associated soil microbial functional group abundance under salt stress. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 165, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, D.R.; Pena, R.; Zotz, G.M.; Albach, D.C. Effects of fungal inoculation on the growth of Salicornia (Amaranthaceae) under different salinity conditions. Symbiosis 2021, 84, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portman, T.A.; Granath, A.; Mann, M.A.; El Hayek, E.; Herzer, K.; Cerrato, J. M.; Rudgers, J. A. Characterization of root-associated fungi and reduced plant growth in soils from a New Mexico uranium mine. Mycologia 2023, 115, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, G.; He, Y.; Zhan, F. Dark septate endophyte Exophiala pisciphila promotes maize growth and alleviates cadmium toxicity. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 4, 1165131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, Y.; Tan, J.; Xiong, Y.; (...), Ding, Y.; Xu, Z. The responses and detoxification mechanisms of dark septate endophytes (DSE), Exophiala salmonis, to CuO nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2023, 30, 13773–13787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Tang, M. Effect of dark septate endophytic fungus Gaeumannomyces cylindrosporus on plant growth, photosynthesis and Pb tolerance of maize (Zea mays L.). Pedosphere 2017, 27, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Cornejo, L.; Pacheco, L.; Camargo-Ricalde, S.L.; González-Chávez, M.D.C. Endorhizal fungal symbiosis in lycophytes and metal(loid)-accumulating ferns growing naturally in mine wastes in Mexico. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2023, 25, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.S.; Yu, Z.N.; Gui, Y.; Liu, Z.Y. A novel technique for isolating orchid mycorrhizal fungi. Fungal Div. 2008, 33, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, D.G.; Kovács, G.M.; Zajta, E.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Dark septate endophytic pleosporalean genera from semiarid areas. Persoonia 2015, 35, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruotsalainen, A.L.; Kauppinen, M.; Wäli, P.R.; Saikkonen, K.; Helander, M.; Tuomi, J. Dark septate endophytes: Mutualism from by-products? Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, A.; Jain, R.; Pandey, A. Contribution of root-associated microbial communities on soil quality of Oak and Pine forests in the Himalayan ecosystem. Trop. Ecol. 2019, 60, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Dai, D.; Tang, M. Inoculation with ectomycorrhizal fungi and dark septate endophytes contributes to the resistance of Pinus spp. in to pine wilt disease. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 687304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H; Wang, C; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Tang, M. The dark septate endophytes and ectomycorrhizal fungi effect on Pinus tabulaeformis Carr. seedling growth and their potential effects to pine wilt disease resistance. Forests, 2019, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukešová, T.; Kohout, P.; Větrovský, T.; Vohník, M. The potential of dark septate endophytes to form root symbioses with ectomycorrhizal and ericoid mycorrhizal middle european forest plants. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diene, O.; Wang, W.; Narisawa, K. Pseudosigmoidea ibarakiensis sp. nov., a dark septate endophytic fungus from a cedar forest in Ibaraki, Japan. Microbes Environ. 2013, 28, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade-Linares, D.R.; Grosch, R.; Restrepo, S.; Krumbein, A.; Franken, P. Effects of dark septate endophytes on tomato plant performance. Mycorrhiza 2011, 21, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhro, A.; Andrade-Linares, D.R.; von Bargen, S.; Bandte, M.; Buttner, C.; Grosch, R.; Schwarz, D.; Franken, P. Impact of Piriformospora indica on tomato growth and on interaction with fungal and viral pathogens. Mycorrhiza 2010, 20, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuna-Avila, P.; Barrow, J. In vitro system to determine the role of Aspergillus ustus on Daucus carota Roots. Terra Latinoamericana 2009, 27, 363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.; Diánez, F. Strain of Rutstroemia calopus, compositions and uses. 2017. Patent ES2907599. 7599.

- Zhang, M.; Yang, M.; Shi, Z.; Gao, J.; Wang, X. Biodiversity and variations of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with roots along elevations in Mt. Taibai of China. Diversity 2022, 14, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malicka, M.; Magurno, F.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Plant association with dark septate endophytes: When the going gets tough (and stressful), the tough fungi get going. Chemosphere 2022, 302, 134830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madouh, T.A.; Quoreshi, A.M. The Function of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Associated with Drought Stress Resistance in Native Plants of Arid Desert Ecosystems: A Review. Diversity 2023, 15, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, D.; Sunkar, R. Drought and salt tolerance in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2005, 24, 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, P.; Schnug, E. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidant responses and implications from a microbial modulation perspective. Biology 2022, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muley, A.B.; Shingote, P.R.; Patil, A.P.; Dalvi, S.G.; Suprasanna, P. Gamma radiation degradation of chitosan for application in growth promotion and induction of stress tolerance in potato (Solanum tuberosum L). Carbohydr Polym 2019, 210, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, H.K.; Banerjee, D. Drought alleviation efficacy of a galactose rich polysaccharide isolated from endophytic Mucor sp. HELF2: A case study on rice plant. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, K.; Upadhyay, N.; Kumar, N. Abscisic acid signaling and abiotic stress tolerance in plants: A review on current knowledge and future prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Cui, K.; Wang, R. Multi-omics joint analysis reveals how Streptomyces albidoflavus OsiLf-2 assists Camellia oleifera to resist drought stress and improve fruit quality. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, G.C.; Nunes, K.G.; Soares, M.A. Dark septate endophytic fungi mitigate the effects of salt stress on cowpea plants. Brazilian. Brazilian. J. Microbiol. 2020, 51, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.L.; Hamayun, M.; Kim, Y.H.; Kang, S.M.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, I.J. Gibberellins producing endophytic Aspergillus fumigatus sp. LH02 influenced endogenous phytohormonal levels, isoflavonoids production and plant growth in salinity stress. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamayun, M.; Hussain, A.; Khan, S.A. Gibberellins producing endophytic fungus Porostereum spadiceum AGH786 rescues growth of salt affected soybean. Front Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Hamayun, M.; Kang, S.M. Endophytic fungal association via gibberellins and indole acetic acid can improve plant growth under abiotic stress: An example of Paecilomyces formosus LHL10. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.R. Atypical morphology of dark septate fungal root endophytes of Bouteloua in arid southwestern USA rangelands. Mycorrhiza 2003, 13, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadok, W.; Schoppach, R. Potential involvement of root auxins in drought tolerance by modulating nocturnal and daytime water use in wheat. Ann. Bot. 2019, 124, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ren, Y.; He, C.; Yao, J.; Wei, M.; He., X. Complementary effects of dark septate endophytes and Trichoderma strains on growth and active ingredient accumulation of Astragalus mongholicus under drought stress. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, P.; Yu, D. Microbial diversity of upland rice roots and their influence on rice growth and drought tolerance. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, F.; Samsampour, D.; Askari Seyahooei, M.; Bagheri, A.; Soltani, J. Fungal endophytes alleviate drought-induced oxidative stress in mandarin (Citrus reticulata L.): Toward regulating the ascorbate–glutathione cycle. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261, 108991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Han, T.; Tan, L.; Li, X. Effects of dark septate endophytes on the performance and soil microbia of Lycium ruthenicum under drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 898378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Hou, L.; Liu, J. Growth-promoting effects of dark septate endophytes on the non-mycorrhizal plant Isatis indigotica under different water conditions. Symbiosis 2021, 85, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari Saravi, H.; Gholami, A.; Pirdashti, H.; Baradaran Firouzabadi, M.; Asghari, H.; Yaghoubian, Y. Improvement of salt tolerance in Stevia rebaudiana by co-application of endophytic fungi and exogenous spermidine. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 177, 114–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.L.; Li, Y.; Tian, W. A novel dark septate fungal endophyte positively affected blueberry growth and changed the expression of plant genes involved in phytohormone and flavonoid biosynthesis. Tree Physiol. 2021, 40, 1080–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likar, M.; Regvar, M. Isolates of dark septate endophytes reduce metal uptake and improve physiology of Salix caprea L. Plant Soil 2013, 370, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, X. Dark septate endophyte improves the drought-stress resistance of Ormosia hosiei seedlings by altering leaf morphology and photosynthetic characteristics. Plant Ecol. 2021, 222, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, X. Dark septate endophyte improves drought tolerance of Ormosia hosiei Hemsley & E.H. Wilson by modulating root morphology, ultrastructure, and the ratio of root hormones. Forests 2019, 10, 830. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, F.; He, Y.; Zu, Y.; Li, T.; Zhao, Z. Characterization of melanin isolated from a dark septate endophyte (DSE), Exophiala pisciphila. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 2483–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, H.; Chen, J.M.; Zhang, Y. The applicability of empirical vegetation indices for determining leaf chlorophyll content over different leaf and canopy structures. Ecol. Complex. 2014, 17, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogburn, R.M.; Edwards, E.J. Quantifying succulence: A rapid, physiologically meaningful metric of plant water storage. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1533–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Hou, J.; Li, X. Dual inoculation of dark septate endophytes and Trichoderma viride drives plant performance and rhizosphere microbiome adaptations of Astragalus mongholicus to drought. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukumar, T.; Vediyappan, S. Comparison of arbuscular mycorrhizal and dark septate endophyte fungal associations in soils irrigated with pulp and paper mill effluent and well-water. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2010, 46, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Santos, S.G.; Silva, P.R.A.; Garcia, A.C.; Zilli, J.É.; Berbara, R.L.L. Dark septate endophyte decreases stress on rice plants. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwari, D.K.; Dheeman, S. Endophytes in mineral nutrient management: Introduction in endophytes: Mineral nutrient management: Introduction. In Endophytes in mineral nutrient management: Introduction in endophytes: Mineral nutrient management. Maheshwari, D. K., Dheeman, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing 2021, 3, 3-9.

- Khan, N.M.; Rastoskuev, V.V.; Sato, Y.; Shiozawa, S. Assessment of hydrosaline land degradation by using a simple approach of remote sensing indicators. Agric. Water Manag. 2005, 77, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Latorre, C.; Rodrigo, S.; Santamaría, O. Endophytes as plant nutrient uptake-promoter in plants. In Endophytes: Mineral Nutrient Management, Maheshwari, D. K., Dheeman, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing (Springer, Cham.) 2021, 3, 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Diksha; Sindhu, S.S.; Kumar, R. Biofertilizers: An ecofriendly technology for nutrient recycling and environmental sustainability. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Cook, J.; Nearing, J.T.; Zhang, J.; Raudonis, R.; Glick, B.R.; Langille, M.G.I; Cheng, Z. Harnessing the plant microbiome to promote the growth of agricultural crops. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 245, 126690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, N.; Sukla, L. Solubilization of inorganic phosphates by fungi isolated from agriculture soil. African J. Biotechnol. 2006, 5, 850–854. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N.; Sabat, J.; Parida, R.; Kerkatta, D. Solubilization of tricalcium phosphate and rock phosphate by microbes isolated from chromite, iron and manganese mines. Acta Bot. Croat. 2007, 66, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, B.A.; Jumpponen, A.; Trappe, J.M. Utilization of major detrital substrates by dark-septate, root endophytes. Mycologia 2000, 92, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Li, T.; Shen, M.; Yang, Z.L.; Zhao, Z.W. Evidence for a dark septate endophyte (Exophiala Pisciphila, H93) enhancing phosphorus absorption by maize seedlings. Plant Soil 2020, 452, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byregowda, R.; Prasad, S.R.; Oelmüller, R.; Nataraja, K.N.; Kumar, M.K. Is endophytic colonization of host plants a method of alleviating drought stress? Conceptualizing the hidden world of endophytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.H; Abd El-Megeed, F.H.; Hassanein, N.M.; Youseif, S.H.; Farag, P.F.; Saleh, S.A.; Abdel-Wahab, B.A.; Alsuhaibani, A.M.; Helmy, Y.A.; Abdel-Azeem, A.M. Native rhizospheric and endophytic fungi as sustainable sources of plant growth promoting traits to improve wheat growth under low nitrogen input. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Arredondo, D.L.; Leyva-González, M.A.; González-Morales, S.I.; López-Bucio, J; Herrera-Estrella, L. Phosphate nutrition : Improving low-phosphate tolerance in crops. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 95–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, J.; Sharpley, A.; Pierzynski, G.; Mcdowell, R. Chemistry, cycling, and potential movement of inorganic phosphorus in soils. agriculture and the environment sims, J.T; Sharpley, A.N., Ed.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, usa, 2005; pp. 53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Han, R.; Cao, Y.; Turner, B. Enhancing phytate availability in soils and phytate-p acquisition by plants: A review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9196–9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikheev, V.S.; Struchkova, I.V.; Ageyeva, M.N.; Brilkina, A.A.; Berezina, E.V. The role of Phialocephala fortinii in improving plants’ phosphorus nutrition: New puzzle pieces. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Boukhris, I.; Pragya; Kumar, V.; Yadav, A.N.; Farhat-Khemakhem, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, D.; Blibech, M.; Chouayekh, H.; Alghamdi, O. Contribution of microbial phytases to the improvement of plant growth and nutrition: A review. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surono, S.; Narisawa, K. The dark septate endophytic fungus Phialocephala fortinii is a potential decomposer of soil organic compounds and a promoter of Asparagus officinalis growth. Fungal Ecol. 2017, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakti, W.; Kovács, G.M.; Vági, P.; Franken, P. Impact of dark septate endophytes on tomato growth and nutrient uptake. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2018, 11, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoletti, F.N.; Tobar, N.E.; Fernández Di Pardo, A.; Chiocchio, V.M.; Lavado, R.S. Dark septate endophytes present different potential to solubilize calcium, iron and aluminum phosphates. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 111, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barresi, O.; Lavado, R.S.; Chiocchio, V.M. Can dark septate endophytic fungi (DSE) mobilize selectively inorganic soil phosphorus thereby promoting sorghum growth? A preliminary study. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2022, 54, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadharsini, P.; Muthukumar, T. The root endophytic fungus Curvularia geniculata from Parthenium hysterophorus roots improves plant growth through phosphate solubilization and phytohormone production. Fungal Ecol. 2017, 27, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, B.; Pragash, G.; Cletus, J.; Gurusamy, R.; Sakthivel, N. Simultaneous phosphate solubilization potential and antifungal activity of new fluorescent pseudomonad strains, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. plecoglossicida and P. mosselii. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 25, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Kuga, Y.; Saito, M.; Peterson, R. Vacuolar localization of phosphorus in hyphae of Phialocephala fortinii, a dark septate fungal root endophyte. Can. J. Microbiol. 2006, 5, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.; Saito, K. Role of cell wall polyphosphates in phosphorus transfer at the arbuscular interface in mycorrhizas. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 725939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtomo, R.; Saito, M. Polyphosphate dynamics in mycorrhizal roots during colonization of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. New Phytol. 2005, 167, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrol, N.; Azcón-Aguilar, C. , Pérez-Tienda, J. Arbuscular mycorrhizas as key players in sustainable plant phosphorus acquisition: An overview on the mechanisms involved. Plant Sci. 2019, 280, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno de Mesquita, C.; Sartwell, S.A.; Ordemann, E.V.; Porazinska, D.L.; Farrer, E.C.; King, A.J.; Spasojevic, M.J.; Smith, J.G.; Suding, K.N.; Schmidt, S.K. Patterns of root colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate endophytes across a mostly-unvegetated, high-elevation landscape. Fungal Ecol. 2018, 36, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumpponen, A.; Mattson, K.; Trappe, J. Mycorrhizal functioning of Phialocephala fortinii with Pinus contorta on glacier forefront soil: Interactions with soil nitrogen and organic matter. Mycorrhiza 1998, 7, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.M.; Fan, X.M.; Zhang, G.Q.; Li, B.; Li, M.R.; Zu, Y.Q.; Zhan, F.D. Influences of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate endophytes on the growth, nutrition, photosynthesis, and antioxidant physiology of maize. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2019, 22, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Della Monica, I.F.; Saparrat, M.C.N.; Godeas, A.M.; Scervino, J.M. The co-existence between DSE and AMF symbionts affects plant P pools through P mineralization and solubilization processes. Fungal Ecol. 2015, 17, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, C.; Campos Araujo, K.M.; Soares, L.A.; de Souza, S.R.; Azevedo, L.S.; Santa-Catarina, C.; da Silva, K; Duarte, G.M.; Ribeiro, G.X.; Zilli, J.E. Contribution of dark septate fungi to the nutrient uptake and growth of rice plants. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsham, K.K. A meta-analysis of plant responses to dark septate root endophytes. New Phytol 2011, 190, 3–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoletti, F.; Giacometti, R. Dark septate endophytic fungi (DSE) response to global change and soil contamination. In: Hasanuzzaman, M. (eds) Plant Ecophysiology and Adaptation under Climate Change: Mechanisms and Perspectives II. Springer, Singapore. Springer Singapore, 2020; 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, L.; Ren, Y.; Wang, S.; Su, F. Dark septate endophytes isolated from a xerophyte plant promote the growth of Ammopiptanthus mongolicus under drought condition. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, G.K.; Saxena, S. Plant growth promotion and abiotic stress mitigation in rice using endophytic fungi: Advances made in the last decade. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 209, 105312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, C.; Araujo, K.E.C.; Urquiaga, S.; Schultz, N.; de Carvalho, F.B.; Medeiros, P.S.; Santos, L.A.; Xavier, G.R.; Zilli, J.E. Dark Septate endophytic fungi help tomato to acquire nutrients from ground plant material. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuki, F.; Narisawa, K. A mutualistic symbiosis between a dark septate endophytic fungus, Heteroconium chaetospira, and a nonmycorrhizal plant, Chinese cabbage. Mycologia 2007, 99, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, C.; Araujo, K.E.C.; Urquiaga, S.; Santa-Catarina, C.; Schultz, N.; da Silva Araújo, E.; de Carvalho Balieiro, F.; Xavier, G.R.; Zilli, J.É. Dark septate endophytic fungi increase green manure-15N recovery efficiency, N contents, and micronutrients in rice grains. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, C.; Araujo, K.E.C.; Sperandio, M.V.L.; Santos, L.A.; Urquiaga, S.; Zilli, J.É. Dark septate endophytic fungi increase the activity of proton pumps, efficiency of 15N recovery from ammonium sulphate, N content, and micronutrient levels in rice plants. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsomme, P.; Boutry, M. The plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase: Structure, function and regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr 2000, 1465, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandyam, K.; Jumpponen, A. Seeking the elusive function of the root-colonising dark septate endophytic fungi. Stud. Mycol. 2005, 53, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; White, J.; Arnold, A.E. Redman, R. Fungal endophytes: Diversity and functional roles. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, Y. Colonization by dark septate endophytes improves the growth and rhizosphere soil microbiome of licorice plants under different water treatments. Appl Soil Ecol 2021, 166, 103–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.; Ding, J.; Lin, W.; Li, Q.; Xu, C.; Zheng, Q.; Li, Y. Alleviation of the detrimental effect of water deficit on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) growth by an indole acetic acid-producing endophytic fungus. Plant Soil 2019, 439, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholdy, B.A.; Berreck, M.; Haselwandter, K. Hydroxamate siderophore synthesis by Phialocephala fortinii, a typical dark septate fungal root endophyte. Biometals 2001, 14, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.; Holmstrom, S. Siderophores in environmental research: Roles and applications. Microb. Biotechnol. 2014, 7, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajula, M.; Tejesvi, M.V.; Kolehmainen, S.; Mäkinen, A.; Hokkanen, J.; Mattila, S.; Pirttilä, A.M. The siderophore ferricrocin produced by specific foliar endophytic fungi in vitro. Fungal Biol. 2010, 114, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, H.; Eisendle, M.; Turgeon, B.G. Siderophores in fungal physiology and virulence. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2008, 46, 149–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tienaho, J.; Karonen, M.; Muilu-Mäkelä, R.; Wähälä, K.; Leon Denegri, E.; Franzén, R.; Karp, M.; Santala, V.; Sarjala, T. Metabolic profiling of water-soluble compounds from the extracts of dark septate endophytic fungi (DSE) isolated from scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) seedlings using UPLC-Orbitrap-MS. Molecules 2019, 24, 12–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bi, Y.; Christie, P. Effects of extracellular metabolites from a dark septate endophyte at different growth stages on maize growth, root structure and root exudates. Rhizosphere 2023, 25, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bi, Y.; Quan, W.; Christie, P. Growth and metabolism of dark septate endophytes and their stimulatory effects on plant growth. Fungal Biol. 2022, 126, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Gong, S.; Yang, L.; Hao, J.; Xue, M.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, X.; Shi, W.; Wang, H.; Yu, D. Biocontrol potential of endophytic fungi in medicinal plants from Wuhan Botanical Garden. Biol. Cont. 2016, 94, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scervino, J.M.; Gottlieb, A.M.; Silvani, V.; Pérgola, M. Exudates of dark septate endophyte (DSE) modulate the development of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus (AMF) Gigaspora rosea. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1753–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, C.; He, X.; Su, F.; Hou, L.; Ren, Y.; Hou, Y. Dark septate endophytes improve the growth of host and non-host plants under drought stress through altered root development. Plant Soil 2019, 439, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.M.; Fan, X.M.; Zhang, G.Q.; Li, B. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate endophytes on maize performance and root traits under a high cadmium stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 134, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohník, M.; Albrechtová, J. The co-occurrence and morphological continuum between ericoid mycorrhiza and dark septate endophytes in roots of six European rhododendron species. Folia Geobot. 2011, 46, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiori, B.; Rubini, A.; Riccioni, C. Diversity of endophytic and pathogenic fungi of saffron (Crocus sativus) plants from cultivation sites in Italy. Diversity 2021, 13, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingfei, L.; Anna, Y.; Zhiwei, Z. Seasonality of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis and dark septate endophytes in a grassland site in Southwest China. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005, 54, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, M.S.; Rahman, S.U.; Ismaiel, M.S. Coexistence of arbuscular mycorrhizae and dark septate endophytic fungi in an undisturbed and a disturbed site of an arid ecosystem. Symbiosis 2009, 49, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.L.; French, K. Soil nutrients differentially influence root colonisation patterns of AMF and DSE in Australian plant species. Symbiosis 2021, 83, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Urbano, M.; Goicoechea, N.; Velasco, P.; Poveda, J. Development of agricultural bio-inoculants based on mycorrhizal fungi and filamentous fungi: Co-inoculants for improve plant-physiological responses in sustainable agriculture. Biol. Cont. 2023, 182, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, F.; Reinsch, S.; Goodall, T.; White, N.; Jones, D.L.; Griffiths, R.; Creer, S.; Smith, A.; Emmett, B.A.; Robinson, D.A. Long-term drought and warming alter soil bacterial and fungal communities in an upland heathland. Ecosystems 2022, 25, 1279–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas, L.H.; Becker, S.R.; Cruz, V.M.V.; Byrne, P.F.; Dierig, D.A. Root traits contributing to plant productivity under drought. Front. Plant Sci 2013, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Shang, X. J.; Luo, Q. X.; Yan, Q.; Hou, R. Effects of the dual inoculation of dark septate endophytes and Trichoderma koningiopsis on blueberry growth and rhizosphere soil microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2023, 99, fiad008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, C.L.; White, M.; Serpe, M.D. Co-inoculation with a dark septate endophyte alters arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization of two widespread plants of the sagebrush steppe. Symbiosis 2021, 85, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deram, A.; Languereau, F.; Haluwyn, C.V. Mycorrhizal and endophytic fungal colonization in Arrhenatherum elatius L. roots according to the soil contamination in heavy metals. Soil Sediment. Contam. 2011, 20, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soteras, F.; Renison, D.; Becerra, A.G. Growth response, phosphorus content and root colonization of Polylepis australis Bitt. seedlings inoculated with different soil types. New For. 2013, 44, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, C.; Blaudez, D.; Beguiristain, T. Co-inoculation of Lolium perenne with Funneliformis mosseae and the dark septate endophyte Cadophora sp. in a trace element-polluted soil. Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininger, V.; Sieber, T.N. Mycorrhiza reduces adverse effects of dark septate endophytes (DSE) on growth on conifers. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Matsuoka, Y.; Miura, T.; Nishizawa, T. Ohta, H. Complete genome sequence of Agrobacterium pusense VsBac-Y9, a bacterial symbiont of the dark septate endophytic fungus Veronaeopsis simplex Y34 with potential for improving fungal colonization in roots. J. Biotechnol, 2018, 284, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Luo, R.; Wang, S. Effect of inoculation on the mechanical properties of alfalfa root system and the shear strength of mycorrhizal composite soil. J. China Coal. Soc. 2022, 47, 2182–2192. [Google Scholar]

- Valli, P.S.; Muthukumar, T. Dark Septate Root Endophytic Fungus Nectria haematococca Improves Tomato Growth Under Water Limiting Conditions. Indian J. Microbiol. 2018, 58, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Songachan, L.S.; Kayang, H. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with Flemingia vestita Benth ex Bak. Mycology 2013, 4, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravesi, K.; Ruotsalainen, A.L.; Cahill, J.F. Contrasting impacts of defoliation on root colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal and dark septate endophytic fungi of Medicago sativa. Mycorrhiza 2015, 24, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, G.L.; Mendonça, J.J.; Teixeira, J.L. , Mangieri de Oliveira, Exotic arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and native dark septate endophytes on the initial growth of Paspalum millegrana grass. Rev. Caatinga 2019, 32, 607–615. [Google Scholar]

- Guo; X., Wan; Y., Hu; J., Wang; D. Dual inoculations of dark septate endophytic and ericoid mycorrhizal fungi improved the drought resistance of blueberry seedlings. SSRN 2022. [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.S.T; Cassiolatto, A.M.R.; Galindo, F.S.; Jalal, A.; Nogueira, T.A.R.; Oliveira; C.E.; Filho, M.C. M. T. Azospirillum brasilense and zinc rates effect on fungal root colonization and yield of wheat-maize in tropical savannah conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, L.; Gao, R.; Hou; X.; Yu, X.; Yang, X. Arbuscular mycorrhizal and dark septate endophyte colonization in Artemisia roots responds differently to environmental gradients in eastern and central China. Sci ToTENV 2021, 795, 148808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendirakumar, K.; Chongtham, I.; Pandey, R. R.; Muthukumar, T. Arbuscular mycorrhizal and dark septate endophytic fungal symbioses in Parkia timoriana (DC. in Merr. and Solanum betaceum Cav. plants growing in North East India. Vegetos 2021, 34, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, M.A.; Menoyo, E.; Allione, L.R.; Negritto, M.A.; Henning, J.A.; Anton, A.M. Arbuscular mycorrhizas and dark septate endophytes associated with grasses from the Argentine Puna. Mycologia 2018, 110, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruotsalainen, A.L.; Vatre, H.; Vestberg, M. Seasonality of root fungal colonization in low alpine herbs. Mycorrhiza 2002, 12, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.H. Colonization investigation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and dark septate endophytes (DSE) in roots of Polygonatum kingianum and their correlations with content of main functional components in rhizomes. Chinese Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2019, 24, 3930–3936. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, M.; Bai, N.; Wang, P.; Su, J.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, Q. Co-Inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate endophytes under drought stress: Synergistic or competitive effects on maize growth, photosynthesis, root hydraulic properties and aquaporins? Plants 2023, 12, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, A.A.; Currah, R. A comparative study of the effects of the root endophytes Leptodontidium orchidicola and Phialocephala fortinii (Fungi Imperfecti) on the growth of some subalpine plants in culture. Can. J. Bot. 1996, 74, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Li, M.; Liu, R. Combination effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate endophytes on promoting growth of cucumber plants and resistance to nematode disease. Mycosystema 2016, 35, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Reininger, V.; Sieber, T.N. Mitigation of antagonistic effects on plant growth due to root co-colonization by dark septate endophytes and ectomycorrhiza. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 5, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghoubian, Y.; Goltapeh, E.M.; Pirdashti, H. Effect of Glomus mosseae and Piriformospora indica on growth and antioxidant defense responses of wheat plants under drought stress. Agric. Res. 2014, 3, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anith, K.N.; Faseela, K.M.; Archana, P.A.; Prathapan, K.D. Compatibility of Piriformospora indica and Trichoderma harzianum as dual inoculants in black pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Symbiosis 2011, 55, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrus, D.A.; Dougherty, K.; Arendt, K.R.; Huntermann, M; Clum, A.; Pillay, M.; Palaniappan, K; Varghese, N.; Mikhailova, N.; Stamatis, D.; Reddy, T.B.K.; Ngan, C.Y.; Daum, C.; Shapiro, N.; Markowitz, V.; Ivanova, N.; Kyrpides, N.; Woyke, T.; Arnold, A.E. Absence of genome reduction in diverse, facultative endohyphal bacteria. Microb Genom. 2017, 3, e000101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Matsuoka, Y.; Nishizawa, T.; Ohta, H.; Narisawa, K. Effects of Rhizobium Species Living with the Dark Septate Endophytic Fungus Veronaeopsis simplex on Organic Substrate Utilization by the Host. Microbes Environ 2018, 33, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, T.; He, X. Mycorrhizal and dark septate endophytic fungi under the canopies of desert plants in Mu Us Sandy Land of China. Front Agric China 2009, 3, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Bi, Y.; Ma, S.; Shang, J.; Hu, Q; Christie, P. Combined inoculation with dark septate endophytes and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: Synergistic or competitive growth effects on maize? BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bending, G.D.; Rodriguez-Cruz, M.S.; Lincoln, S.D. Fungicide impacts on microbial communities in soils with contrasting management histories. Chemosph. 2007, 69, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernaghan, G; Griffin, A.; Gailey, J. Hussain, A. Tannin tolerance and resistance in dark septate endophytes. Rhizosphere 2022, 23, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno de Mesquita, C.P.; Solon, A.J.; Barfield, A.; Mastrangelo, C.F. Adverse impacts of Roundup on soil bacteria, soil chemistry and mycorrhizal fungi during restoration of a Colorado grassland. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 185, 104778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoletti, V.M.; Chiocchio, F.N. Tolerance of dark septate endophytic fungi (DSE) to agrochemicals in vitro. Rev. Argentina Microbiol. 2020, 52, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalu, J.N.; Soekarno, B.P.W.; Tondok, E.T.; Surono, S. Isolation and capability of dark septate endophyte against mancozeb fungic. Ilmu Pertan Indones 2020, 25, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, G.S.; Charudattan, R.; Rosskopf, E.N. Littell, R.C. Effects of selected pesticides and adjuvants on germination and vegetative growth of Phomopsis amaranthicola, a biocontrol agent for Amaranthus spp. Weed Res. 2002, 44, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyaningsih, S.; Triasih, U. Pesticides effect on growth of dark septate endophytes in vitro IOP Conf. 012037 IOP Int. Conf Sustain. Agric. 2023, 1172, 012037. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, F.; He, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Zhao, Z. Effects of tricyclazole on cadmium tolerance and accumulation characteristics of a Dark Septate Endophyte (DSE. in Exophiala pisciphila. Bull. Environ. Contami. Toxicol. 2016, 96, 235–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayesha, M. S.; Suryanarayanan, T. S.; Nataraja, K. N.; Rajendra, S.P.; Shaanker, R.U. Seed treatment with systemic fungicides. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 2, 654512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugtenberg, B.J.; Caradus, J.R.; Johnson, L.J. Fungal endophytes for sustainable crop production. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DSE species | Co-inoculum | Host plant | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Acrocalymma vagum Paraboeremia putaminum |

Trichoderma viride | Astragalus mongholicus | [56] |

| Alternaria sp. | Diversispora epigaea | Zea mays | [134] |

| Amnesia nigricolor | Trichoderma koningiopsis | Vaccinium corymbosum | [122] |

| Cadophora sp. | Funneliformis mosseae | Lolium perenne | [126] |

| Cladosporium cladosporioides | Oidiodendron citrinum | Vaccinium corymbosum | [127] |

| Darksidea | Rhizophagus irregularis |

Artemisa tridentata Poa secunda |

[123] |

| DSE |

Azospirillum brasilense AMF |

Zea mays Triticum aestivum |

[135] |

| DSE | AMF | Medicago sativa | [129] |

| DSE | AM | Artemisia sp. | [136] |

| DSE | AM |

Parkia timoriana Solanum betaceum |

[137] |

| DSE | AM | Poaceae | [138] |

| DSE | AM |

Alchemilla glomerulans Carex vaginata Ranunculus acris ssp. pumilus Trollius europaeus |

[139] |

| DSE | AMF | Polygonatum kingianum | [140] |

| DSE |

Rhizoglomus clarum Claroideoglomus etunicatum Acaulospora morrowiae |

Paspallum millegrana | [133] |

| Exophiala pisciphila | Funneliformis mosseae | Zea mays | [87,113] |

| Exophiala pisciphila | Rhizophagus irregularis | Zea mays | [141] |

| Phialocephala fortinii | Glomus intraradices | Medicago sativa | [100] |

| Phialocephala fortinii | Leptodontidium orchidicola |

Potentilla fruticosa Dryas octopetala Salix glauca Picea glauca |

[142] |

| Phoma leveillei | Acaulospora laevis | Cucumis sativus | [143] |

|

Macrophomina pseudophaseolina Paraphoma radicina |

T. afroharzianum, T. longibrachiatum |

Astragalus mongholicus | [43] |

| Paraphoma chrysanthemicolaGaeumannomyces cylindrosporus |

Suillys bovinus Amanita vaginata |

Pinus tabulaeformis | [20] |

|

Phialocephala turiciensis Acephala applanata P. glacialis Phaeomollisia piceae |

Gigaspora rosea | Trifolium repens | [88] |

|

Phialocephala fortinii Phialocephala subalpina |

Laccaria bicolor | Pseudotsuga menziesii | [127] |

| Phialocephala fortiniis.l.–Acephala applanata species complex (PAC) | Hebeloma crustuliniforme | Picea abies | [144] |

| Piriformospora indica | Glomus mosseae | Triticum aestivum | [145] |

| Piriformospora indica | T. harzianum | Piper nigrum | [146] |

|

Cladosporium cladosporioides Exophiala salmonis Phialophora mustea Paraphoma chrysanthemicola Gaeumannomyces cylindrosporus |

Schizophyllum sp. Suillus laricinus Amanita vaginata Handkea utriformis Suillus tomentosus Suillus bovinus Suillus lactifluus |

Pinus tabulaeformis | [19] |

|

Acephala applanate Phialocephala europaea Phialocephala fortinii Phialocephala Helvetica Phialocephala letzii Phialocephala subalpina Phialocephala turiciensis Phialocephala uotolensis Acephala macrosclerotiorum Phialocephala glacialis |

Paxillus involutus Rhizoscyphus ericae |

Vaccinium corymbosum | [21] |

| Veronaeopsis simplex | Agrobacterium pusense | Solanum lycopersicum | [128] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).