1. Introduction

The hospitality industry plays a pivotal role in shaping the perceptions and experiences of customers, reflecting the cultural and social dynamics of a given region. In post-apartheid South Africa, where historical racial tensions persist, examining the interactions between African customers and staff members in white-owned restaurants and hotels becomes a critical lens through which to understand societal changes and challenges.

South Africa, with its diverse landscapes and rich cultural heritage, has emerged as a prominent destination in the global tourism landscape. The hospitality industry, encompassing a spectrum from upscale hotels to quaint bed-and-breakfast outlets, has witnessed significant growth, attracting a broad range of customers. However, this sector’s evolution has not been immune to the historical complexities that have characterized the nation’s past, particularly the apartheid era.

The apartheid system, which officially ended in 1994, institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination, leaving a lasting impact on social structures. In the aftermath of apartheid, the hospitality industry underwent transformative changes, adapting to the new democratic order and, ostensibly, striving to be inclusive. However, the echoes of historical racial disparities continue to reverberate within the industry, influencing the dynamics between customers and staff members, particularly in establishments owned by individuals of European descent.

Despite the apparent strides towards a more equitable society, anecdotal evidence suggests that African customers may encounter distinctive challenges and varying levels of service quality in establishments owned by white individuals. These challenges are often rooted in historical power imbalances, societal perceptions, and the lingering effects of a deeply divided past.

The post-apartheid era in South Africa has witnessed a surge in discussions surrounding racial reconciliation and social cohesion. However, the hospitality industry’s role in fostering inclusive and unbiased environments has not been comprehensively explored, especially from the perspective of African customers. As such, it becomes imperative to delve into the lived experiences of this specific demographic within white-owned establishments.

The problem at hand lies in understanding the nuanced interactions between African customers and staff members, unravelling the layers of perception and service quality. Do these interactions reflect a genuine commitment to post-apartheid ideals, or do they underscore persistent challenges in dismantling racial hierarchies within the hospitality sector? What narratives emerge when considering the experiences of African customers in the diverse array of establishments, ranging from luxurious hotels to intimate guest houses?

This paper embarks on a qualitative systematic review to address these questions, seeking to amplify the voices of African customers and shed light on the dynamics at play in the post-apartheid South African hospitality industry. By doing so, it aims to contribute valuable insights for both academics and industry practitioners, fostering a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities that exist in building a more inclusive and equitable hospitality landscape.

2. Research Problem

The research aims to investigate the experiences of African customers in white-owned restaurants and hotels in post-apartheid South Africa, with a focus on understanding the dynamics of service interactions and their implications on racial relations within the hospitality industry. The identified problem indicators highlight specific challenges and nuances in this context, as discussed below:

2.1. Problem Indicator 1: Historical Power Imbalances

The legacy of apartheid has left deep-rooted historical power imbalances that continue to influence social dynamics. In the hospitality industry, the interactions between African customers and staff members may be shaped by historical prejudices and hierarchies, leading to disparate treatment. Historical power imbalances manifest in subtle ways, from differential service quality to more overt forms of discrimination, raising questions about the industry’s commitment to dismantling the vestiges of apartheid.

2.2. Problem Indicator 2: Societal Perceptions and Stereotypes

Societal perceptions and stereotypes play a pivotal role in shaping the experiences of African customers in white-owned establishments. Preconceived notions about service expectations, behavior, and cultural understanding may contribute to biased interactions. Stereotypes can manifest in the form of microaggressions, reinforcing racial divides within the hospitality industry. Understanding how these perceptions influence service provision is crucial in dissecting the broader issues of cultural sensitivity and inclusivity.

2.3. Problem Indicator 3: Lingering Effects of Apartheid

Despite the formal end of apartheid, its effects linger in the social fabric of South Africa. The hospitality industry, as a microcosm of society, may grapple with the remnants of systemic discrimination. African customers may encounter challenges rooted in economic disparities, access to opportunities, and a general hesitancy to fully integrate. Exploring how these lingering effects manifest in day-to-day interactions within white-owned establishments unveils the ongoing complexities in achieving genuine post-apartheid transformation.

2.4. Problem Indicator 4: Inclusive Practices and Post-Apartheid Ideals

The extent to which white-owned restaurants and hotels genuinely embody post-apartheid ideals of inclusivity and equality is a central concern. While there may be efforts to project an image of progress, the lived experiences of African customers reveal whether these establishments actively engage in practices that foster a sense of belonging. Evaluating the alignment between proclaimed ideals and the ground-level experiences of customers offers insights into the industry’s commitment to social cohesion and the extent to which it contributes to broader societal change.

2.5. Problem Indicator 5: Varied Experiences Across Hospitality Establishments

The diversity within the hospitality sector, ranging from upscale hotels to intimate bed-and-breakfast outlets, introduces a nuanced layer to the research problem. African customers’ experiences may differ significantly depending on the type of establishment, raising questions about the universality of challenges and the impact of socio-economic factors. Investigating these variations provides a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of racial dynamics within the hospitality industry.

In view of the above, the research problem revolves around the need to dissect the intricate interplay of historical, societal, and economic factors shaping the experiences of African customers in white-owned restaurants and hotels in post-apartheid South Africa. By addressing these problem indicators, the study seeks to unravel the complexities inherent in achieving a truly inclusive and equitable hospitality landscape in the aftermath of apartheid.

3. Research Question

In view of the fact that this study is a qualitative systematic review that seeks to describe experiences as opposed to providing an intervention, the authors opted to use the SPIDER Framework (Cooke, et al., 2012) to craft a research question. Thus, the research question for this study is, “How do African customers in white-owned restaurants and hotels in post-apartheid South Africa perceive and experience service interactions, and what are the underlying factors influencing these perceptions, considering historical power imbalances, societal perceptions, lingering effects of apartheid, inclusive practices, and the varied experiences across different hospitality establishments?

4. Research Objecives

Examine the Dynamics of Service Interactions

Identify Influencing Factors on Perceptions and Experiences

Evaluate Alignment with Inclusive Practices and Post-Apartheid Ideals

Describing experiences of African Perceptions regarding service in Post-Apartheid South Africa

5. Theoretical Framework

A theoretical framework is a critical aspect explicitly stated by educational researchers. It shapes the research questions, informs the method of data collection and analysis, and guides the discussion of study results. It also unveils the researcher’s subjectivities, including values, social experiences, and viewpoints (Allen, 2017). Recognizing and articulating the theoretical framework is crucial for novice researchers, as it reveals the implicit or explicit assumptions underlying their exploration of a phenomenon of interest (Schwandt, 2000). Thus, the theoretical framework not only elucidates the lens through which the phenomenon is examined but also influences the entire research process, from formulating questions to interpreting findings. In this study, the Consumer Brand Theory (CBT) was used to define customer experiences (Popp & Woratschek, 2017).

In the context of exploring African customers’ experiences in the hospitality industry in post-apartheid South Africa, while the Consumer Brand Theory (CBT) as mentioned provides a valuable lens for defining customer experiences by focusing on the relationship between consumers and brands, it is not the only applicable theory. CBT is instrumental in understanding how brand perceptions influence consumer behavior and experiences, particularly in the hospitality sector where brand image and customer perception can significantly impact customer satisfaction and loyalty.

However, other theories could also enrich the research by offering different perspectives and insights into customer experiences:

Service-Dominant Logic (S-D Logic): Proposed by Vargo and Lusch (2004), S-D Logic shifts the focus from transactions to value co-creation between providers and consumers. In the hospitality industry, this perspective can help understand how customers co-create their experiences through interactions with the service environment and personnel, influencing their overall perception of the service.

Experience Economy Theory: Pine and Gilmore (1998) introduced the concept of the experience economy, where businesses are seen as staging experiences to engage customers in a personal and memorable way. This theory could be particularly relevant for the hospitality industry in South Africa, as it emphasizes the importance of creating unique and engaging customer experiences.

Cultural Theory: Considering the socio-cultural context of post-apartheid South Africa, incorporating theories that address cultural dynamics and consumer behavior can provide deeper insights. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory, for example, could help in understanding how cultural values influence customer expectations and experiences in the hospitality sector.

Expectation-Confirmation Theory (ECT): ECT, as proposed by Oliver (1980), is a cognitive theory that explains post-purchase or post-use satisfaction as a function of initial expectations, perceived performance, and confirmation of those expectations. This theory could be particularly useful in understanding customer satisfaction in the hospitality industry.

Relationship Marketing Theory: This theory focuses on long-term customer engagement and the development of ongoing relationships between businesses and their customers. In the context of the hospitality industry, this theory could provide insights into how customer loyalty and repeat business can be fostered through personalized service and customer recognition.

Each of these theories offers a different lens through which to examine customer experiences in the hospitality industry, and their inclusion could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence customer perceptions and behaviors in post-apartheid South Africa. Incorporating multiple theoretical perspectives can also enrich the research design and analysis, providing a more nuanced and multidimensional view of customer experiences.

6. Literature Review

The following literature review is based on the application and operationalization of the research objectives as identified in the previous section (

Section 4). The transition from apartheid to a democratic society in South Africa marked a significant shift in the socio-political landscape, heralding a new era of hope and expectations for equality and improved quality of life for all its citizens. However, the legacy of apartheid, characterized by profound racial, spatial, and economic divisions, continues to influence the country’s development trajectory, particularly in terms of service delivery. This literature review aims to explore the intricate dynamics of service delivery in post-apartheid South Africa, focusing on the disparities that exist across different sectors and communities, the impact of these disparities on social cohesion and identity, and the role of white-owned entities in providing services to the African population.

Service delivery in South Africa is a multifaceted issue that encompasses the provision of basic amenities such as water and electricity, healthcare, education, financial services, and access to hospitality and retail services. Despite the government’s efforts to improve service delivery and address the inequalities inherited from the apartheid regime, significant challenges remain. These challenges are not merely logistical or infrastructural but are deeply entwined with the broader issues of economic inequality, social cohesion, and the quest for a unified national identity.

The review will delve into the economic disparities that underpin the challenges in service delivery, highlighting how the apartheid-era economic structure continues to affect access to quality services. It will examine the state of healthcare, education, and basic utilities, illustrating how inadequacies in these areas contribute to a sense of neglect and marginalization among the African population. Furthermore, the review will consider the role of white-owned businesses in sectors such as banking, hospitality, and healthcare, exploring how their practices may influence service accessibility and quality for African consumers.

In addressing these themes, the review will draw on a range of academic sources, including studies on healthcare and education disparities, analyses of economic inequality, and research on social cohesion and identity in post-apartheid South Africa. Through this comprehensive exploration, the review aims to shed light on the complex interplay between historical legacies, current socio-economic challenges, and the ongoing efforts to build a more equitable and united South African society.

6.1. RO:1: Examination of Service Dynamics Interactions

6.1.1. Investigating Nuanced Experiences of African Customers in White-Owned Establishments

In the landscape of consumer experiences, a compelling exploration unfolds as we delve into the nuanced interactions of African customers within white-owned establishments. This inquiry seeks to unravel the complex layers of identity, culture, and consumption dynamics, offering a deep understanding of the intersectionality at play.

Rooted in the theoretical framework of consumer brand identification (Starkey, 2017), our investigation aims to shed light on the convergence of brand identity and consumer identity. As Addie, Ball, and Adams (2019) point out, consumer brand identification becomes salient when the brand aligns with the social identity of the consumer. This lens proves crucial in understanding the intricate relationships between African customers and white-owned establishments, where cultural dynamics and societal norms come into play.

For African customers, entering white-owned establishments is more than a transactional experience. It involves a negotiation of cultural dynamics, where their individual cultural identities intersect with the dominant culture represented by these establishments (Anaza et al., 2021). This negotiation shapes perceptions, expectations, and the overall consumer experience within these spaces.

In today’s globalized world, brands play a pivotal role in cultural representation (Anaza et al., 2021). For African customers, navigating white-owned establishments involves not only a transaction but also a negotiation of cultural representation. This process is significant in shaping their engagement with brands and their overall consumer experiences.

As highlighted by Starkey (2017), understanding consumer brand identification is crucial for marketers. African customers, like any other consumer group, perceive brands beyond their functional attributes. Brands become an extension of their identity, influencing their choices and preferences. This understanding is vital for businesses and marketers aiming to create inclusive and culturally sensitive environments within white-owned establishments.

In exploring nuanced experiences, our research adopts a qualitative approach, utilizing in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with African customers frequenting white-owned establishments. This method aligns with Creswell’s (2013) recommendation of employing narrative inquiry, allowing participants to share their stories, perspectives, and emotions, providing a rich and contextual understanding of their experiences.

This inquiry into the nuanced experiences of African customers within white-owned establishments serves as a pivotal contribution to the discourse on consumer behavior. By employing the lens of consumer brand identification, we aim to uncover the intricate relationships, challenges, and opportunities at play in these dynamic interactions.

6.1.2. Analyzing Positive and Negative Service Interactions: Impact on Customer Perceptions

In the intricate tapestry of customer relations, the examination of positive and negative service interactions holds paramount importance, influencing customer perceptions in profound ways. This narrative delves into the dynamics of service encounters, exploring their impact on how customers perceive a brand, drawing insights from relevant literature.

The exploration begins with an acknowledgment of the foundational role that service interactions play in shaping customer perceptions. As emphasized by Zeithaml et al. (2009), service encounters serve as critical touchpoints where customers interact directly with a brand, influencing their overall perception of the service quality and the brand itself. Positive service interactions contribute to favorable customer perceptions, fostering loyalty and positive word-of-mouth (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2002).

Conversely, negative service interactions carry the potential to leave lasting impressions that can tarnish customer perceptions. Research by Tax et al. (1998) highlights that dissatisfying service encounters can lead to customer dissatisfaction, negatively impacting brand loyalty and potentially resulting in customers sharing their negative experiences with others. In a world where customer reviews and feedback hold significant sway, negative service interactions can reverberate widely, influencing potential customers and affecting the brand’s reputation.

Understanding the nuances of positive and negative service interactions requires an examination of the factors contributing to customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Service quality, as conceptualized by Parasuraman et al. (1985), plays a pivotal role. Positive service interactions align with customers’ expectations or, ideally, exceed them, leading to increased satisfaction. Negative service interactions, on the other hand, signify a dissonance between customer expectations and the actual service received, causing dissatisfaction.

The impact of service interactions extends beyond individual transactions. Pine and Gilmore (1998) introduced the concept of the “experience economy,” emphasizing that customers seek memorable and positive experiences. Positive service interactions contribute to creating such experiences, enhancing customer perceptions not only of the specific service encounter but also of the brand as a whole. This aligns with the broader notion that service quality is a critical driver of brand equity (Berry, 2000).

Moreover, the emotional dimension of service interactions adds another layer to customer perceptions. Positive service interactions evoke positive emotions, contributing to customer satisfaction (Hocutt et al., 2009). In contrast, negative service interactions can evoke negative emotions, leading to heightened dissatisfaction and potential disengagement with the brand (Oliver, 1993).

Recognizing the significance of service interactions, businesses are increasingly investing in training their frontline staff to enhance customer service skills. Employees’ interpersonal skills, as noted by Bitner et al. (1990), can significantly impact service interactions. Positive and effective communication during service encounters can mitigate potential issues and contribute to positive customer perceptions.

The dynamics of positive and negative service interactions wield considerable influence on customer perceptions. Positive interactions contribute to satisfaction, loyalty, and positive brand associations, while negative interactions can lead to dissatisfaction and potential reputational damage. Understanding the intricacies of these interactions is crucial for businesses aiming to cultivate positive customer perceptions, build brand loyalty, and thrive in the competitive landscape of customer-centric industries.

6.1.3. Assessing Hospitality Staff’s Impact on Service Dynamics and Overall Customer Experience

In the dynamic landscape of the hospitality industry, the influence of staff on service dynamics and the overall customer experience stands as a pivotal factor shaping the success of establishments. This narrative explores the multifaceted dimensions of how hospitality staff significantly impact service quality, drawing insights from recent literature.

Recent research by Choi and Chu (2011) emphasizes the central role of frontline staff in delivering positive customer experiences within the hospitality sector. As the industry is inherently service-oriented, the interactions between staff and customers become critical touchpoints that influence the overall perception of the establishment. Competence and friendliness of staff emerge as key factors influencing customer satisfaction, as highlighted in studies by Kandampully and Suhartanto (2000). Competent and amiable staff contribute to a positive service encounter, ultimately enhancing the overall experience for guests.

The emotional labor undertaken by hospitality staff adds a nuanced layer to service dynamics. Hochschild’s (1983) concept of emotional labor, particularly relevant in the context of the hospitality industry, refers to the effort employees invest in managing their emotions to meet organizational expectations. Recent studies (Brotheridge & Lee, 2003) indicate that emotional labor is a significant aspect of service delivery, impacting customer perceptions and satisfaction. Genuine care and empathy expressed by staff contribute to creating a positive emotional connection with customers, fostering a memorable and satisfying experience.

In the contemporary hospitality landscape, employee engagement has gained prominence as a critical factor influencing service quality. Recent work by Kim and Lee (2016) emphasizes the link between organizational leadership, employee engagement, and customer satisfaction. Engaged employees, who feel connected and committed to their work, are more likely to deliver superior service, enhancing the overall ambiance of the establishment.

Importantly, the impact of hospitality staff extends beyond face-to-face interactions, particularly in the digital era. Harrington and Ottenbacher (2011) highlight the role of online interactions and the digital presence of staff in influencing the overall customer experience. Positive online engagement, responsiveness, and genuine communication with customers through digital channels contribute significantly to shaping the perception of the hospitality brand.

Finally, recent literature underscores the critical role of hospitality staff in influencing service dynamics and overall customer experiences. Competence, friendliness, emotional labor, and employee engagement emerge as key factors that contribute to customer satisfaction, loyalty, and the success of hospitality establishments in a competitive and evolving industry.

6.2. RO 2: Identifying the Influencing Factors on Customer Perceptions and Experiences

This objective is focussed on identification and explication of key factors that influence customer perceptions.

6.2.1. Historical Power Imbalances in Service Provision and Customer Perceptions

In the intricate tapestry of service provision, the historical power imbalances rooted in the legacy of apartheid have left an enduring imprint on customer perceptions, shaping the dynamics between service providers and recipients. This narrative delves into the historical roots of power imbalances in service provision within the context of apartheid and its far-reaching influence on customer experiences, drawing insights from recent literature.

The apartheid era in South Africa, characterized by institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination, significantly shaped power dynamics in various aspects of society, including service provision. The work of Nkomo (2011) highlights that apartheid entrenched deeply rooted social hierarchies, where racial identity determined access to resources, opportunities, and services. This historical backdrop laid the foundation for enduring power imbalances that continue to influence customer perceptions.

Recent studies by Essid (2018) emphasize that the legacies of apartheid persist in contemporary South Africa, impacting customer experiences and interactions. The historical disenfranchisement of certain racial groups has created a backdrop where power imbalances, particularly in service encounters, are perceived through the lens of a painful and unjust history. Customers who have experienced the inequalities of apartheid may approach service interactions with heightened sensitivity to issues of power and fairness.

The influence of apartheid-era power imbalances is evident not only in face-to-face service encounters but also in the broader socio-economic disparities that persist. Research by Harris and Reynolds (2013) points out that economic disparities resulting from apartheid policies continue to shape access to quality services, education, and opportunities. Customers from historically disadvantaged backgrounds may carry these socio-economic disparities into their service interactions, affecting their perceptions of fairness and equality.

Furthermore, the digital age has brought new dimensions to historical power imbalances. Research by Mutsvairo (2016) suggests that digital platforms can either amplify or mitigate existing power imbalances. In the context of apartheid’s historical legacies, the ability to access and utilize digital tools may vary, further influencing the power dynamic within the service exchange. Digital disparities can perpetuate historical inequalities, impacting the overall customer experience.

The historical power imbalances rooted in the era of apartheid have a profound and lasting impact on customer perceptions within the South African context. Recent literature underscores the pervasive nature of these imbalances, extending from traditional service models to contemporary digital interactions. Recognizing and addressing these historical roots are crucial for service providers aiming to foster equitable and positive customer experiences in post-apartheid South Africa.

6.2.2. Societal Perceptions and Stereotypes in African Customer-Hospitality Staff Dynamics

In the intricate interplay between African customers and hospitality staff, societal perceptions and stereotypes weave a complex tapestry that influences the dynamics of service encounters. This narrative explores the multifaceted dimensions of how societal attitudes and preconceived notions impact the interactions between African customers and hospitality staff, drawing insights from recent literature.

The relationship between societal perceptions and hospitality staff dynamics is deeply rooted in cultural and social constructs. Recent research by Anaza et al. (2018) emphasizes that cultural stereotypes can shape the expectations and behaviors of both African customers and hospitality staff. Stereotypes related to hospitality roles or cultural backgrounds can influence how staff approach their interactions and how customers perceive the service they receive.

The impact of societal perceptions is particularly pronounced in the context of racial and ethnic stereotypes. In the hospitality sector, racial biases can shape how staff members perceive and interact with African customers, as highlighted by Okumus et al. (2017). Similarly, African customers may enter service interactions with awareness of prevalent stereotypes, influencing their expectations and responses.

Moreover, the work of Mbaiwa (2017) underscores how societal perceptions extend beyond individual interactions to shape broader service experiences. Hospitality staff, consciously or unconsciously influenced by societal stereotypes, may inadvertently contribute to a sense of exclusion or discomfort for African customers. On the other hand, customers may navigate service encounters with a heightened awareness of how they are perceived based on societal norms and expectations.

The power dynamics inherent in societal perceptions also play a role in service exchanges. Studies by Nkomo (2018) indicate that power imbalances rooted in societal structures can impact the communication and negotiation process between African customers and hospitality staff. These power dynamics may contribute to a sense of vulnerability or marginalization for customers, influencing their overall perception of the service encounter.

The digital era introduces new dimensions to societal perceptions, with online platforms becoming spaces where stereotypes can be perpetuated or challenged. Research by Mutsvairo (2017) suggests that online reviews and social media discussions can reflect and reinforce societal attitudes, affecting the reputation of hospitality establishments and shaping customers’ decisions.

The intricate dynamics between African customers and hospitality staff are significantly influenced by societal perceptions and stereotypes. Recent literature highlights the profound impact of cultural, racial, and power-related stereotypes on service interactions. Acknowledging and addressing these societal dynamics are essential for creating inclusive and positive experiences within the hospitality sector.

6.2.3. Apartheid’s Lingering Effects on African Customer Service Experiences

In the complex tapestry of South Africa’s history, the legacy of apartheid continues to cast a long shadow over contemporary African customer service experiences. This narrative delves into the enduring effects of apartheid on the dynamics between African customers and service providers, drawing insights from recent literature.

The apartheid era, marked by institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination, has left an indelible mark on the social fabric of South Africa. Recent research by Adams (2017) emphasizes that the historical injustices of apartheid persist in the collective memory of the nation, influencing societal attitudes, expectations, and interpersonal dynamics.

One of the lingering effects of apartheid on customer service experiences is evident in the socio-economic disparities that persist. Studies by Seekings and Nattrass (2015) highlight that historical inequalities in access to education, employment, and resources have created enduring socio-economic imbalances. African customers, often hailing from historically disadvantaged backgrounds, may carry the weight of these disparities into service interactions, shaping their expectations and perceptions.

The psychological impact of apartheid is explored by Bhana and Hofmeyr (2016), who argue that the legacy of racial trauma continues to affect individuals and communities. African customers may approach service encounters with heightened sensitivity, influenced by the historical context of systemic discrimination. This psychological baggage can manifest in interactions with service providers, influencing trust, communication, and overall satisfaction.

Moreover, the spatial legacy of apartheid has tangible effects on service accessibility. Research by Turok and Borel-Saladin (2019) highlights the persistent spatial inequalities, where historically disadvantaged communities often have limited access to quality services. This spatial segregation can contribute to disparities in the availability and quality of services for African customers, shaping their service experiences based on geographical factors.

The workplace dynamics within service-oriented industries also reflect the enduring effects of apartheid. Research by Nkomo (2011) emphasizes that power imbalances rooted in historical structures can manifest in the workplace, influencing the treatment of African staff and, consequently, the service experiences of African customers. The echoes of hierarchical structures from the apartheid era may subtly permeate service interactions, affecting the dynamics between staff and customers.

In the digital age, online platforms become spaces where the legacy of apartheid is both reflected and contested. Research by Mutsvairo (2017) suggests that social media discussions and online reviews can amplify or challenge societal attitudes, influencing the reputation of businesses and shaping customer decisions. The digital space serves as a mirror reflecting the ongoing societal dialogue about the consequences of apartheid on service experiences.

Finally, the persistent effects of apartheid continue to reverberate in African customer service experiences. Recent literature underscores that the historical injustices, socio-economic disparities, psychological trauma, spatial inequalities, and workplace dynamics rooted in apartheid collectively contribute to shaping the contours of service interactions. Acknowledging these enduring effects is essential for businesses and policymakers seeking to foster inclusive and equitable customer service experiences in post-apartheid South Africa.

6.3. RO 3: Evaluation of Alignment with Inclusive Practices and Post-Apartheid Ideals

6.3.1. Integrating Post-Apartheid Ideals with African Customer Perceptions

In the wake of the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa, the quest for societal healing and integration of post-apartheid ideals has become intertwined with the dynamics of African customer perceptions. This narrative explores the ongoing journey of integrating post-apartheid ideals with how African customers perceive and engage with various services, drawing insights from recent literature.

The post-apartheid era has ushered in an era of transformative change, characterized by efforts to establish a more inclusive and equitable society. Research by Magadla (2016) emphasizes the importance of acknowledging the historical context of apartheid while striving to build a nation rooted in principles of equality, justice, and reconciliation. The ideals of post-apartheid South Africa inherently shape the societal backdrop against which African customers navigate their service experiences.

One of the key aspects of post-apartheid integration is the emphasis on cultural diversity and inclusivity. The work of Mokubung and Masocha (2017) highlights the importance of recognizing and celebrating diverse cultural identities within the nation. In the realm of customer service, this emphasis on cultural inclusivity is reflected in efforts to understand and respect the cultural nuances of African customers, fostering a more inclusive service environment.

Moreover, the pursuit of economic empowerment and redress for historical inequalities has implications for African customer perceptions. Research by Rwigema and McAllister (2017) discusses the challenges and opportunities associated with economic transformation in post-apartheid South Africa. African customers, particularly those from historically disadvantaged backgrounds, may view economic empowerment initiatives positively if they perceive tangible improvements in access to opportunities and services.

The discourse on reconciliation and nation-building is also integral to the post-apartheid narrative. The work of South African Human Rights Commission (2018) emphasizes the importance of fostering a sense of belonging and shared identity. In the realm of customer service, efforts to create an inclusive and welcoming atmosphere contribute to shaping how African customers perceive their interactions with service providers.

The education sector plays a pivotal role in promoting post-apartheid ideals and fostering awareness. Research by Modiba and Shumba (2018) highlights the role of education in promoting social cohesion and understanding. This has implications for customer service interactions, as a more informed and socially aware customer base may engage with service providers in a way that aligns with the values of post-apartheid South Africa.

The digital landscape provides a platform for the expression of post-apartheid ideals and their integration into customer experiences. Research by Boonzaaier and de Lange (2019) discusses how digital platforms can be harnessed for storytelling and narrative-building that promotes inclusivity and understanding. Social media, in particular, becomes a space where customers and businesses can engage in conversations that reflect and contribute to post-apartheid ideals.

The integration of post-apartheid ideals with African customer perceptions is an ongoing and dynamic process. Recent literature underscores the importance of cultural inclusivity, economic empowerment, reconciliation efforts, education, and the digital space in shaping how African customers engage with various services. This narrative showcases the intricate interplay between historical ideals and contemporary customer experiences in the evolving landscape of post-apartheid South Africa.

6.3.2. Inclusive Policies and Training in the Hospitality Industry

The hospitality industry, with its diverse clientele and multicultural workforce, has been increasingly recognizing the importance of inclusive policies and training to foster a welcoming and equitable environment. Recent literature sheds light on the implementation and impact of such initiatives within the industry.

Inclusive policies in the hospitality sector are designed to create an environment where diversity is not only acknowledged but celebrated. Studies by Gursoy et al. (2017) emphasize that inclusive policies encompass a range of practices, from non-discrimination and equal opportunity policies to initiatives that actively promote diversity in hiring and service provision. These policies extend beyond compliance with legal requirements to foster a culture of inclusivity that resonates with both customers and employees.

Training programs play a pivotal role in translating inclusive policies into actionable practices within the hospitality industry. Research by Tews et al. (2013) underscores the importance of training in shaping employee attitudes and behaviors. Inclusive training goes beyond traditional diversity training by addressing biases, fostering cultural competence, and equipping staff with the skills to navigate diverse interactions effectively. This approach is crucial in an industry where customer satisfaction is deeply intertwined with the quality of service provided.

Furthermore, the work of Saenz et al. (2018) emphasizes that inclusive policies and training are not only responsive to legal and societal expectations but are integral to the strategic success of hospitality businesses. In an era where customers increasingly value socially responsible and ethical practices, businesses that embrace inclusivity can gain a competitive edge. This underscores the broader impact of inclusive policies, extending beyond the internal work culture to influence customer perceptions and loyalty.

The notion of inclusivity in the hospitality industry extends to considerations of accessibility for individuals with disabilities. Recent research by Kim and Lee (2019) highlights the importance of creating physically accessible spaces and training staff to cater to the needs of guests with diverse abilities. Inclusive policies that address physical accessibility, coupled with training initiatives, contribute to creating a hospitable environment for all guests, regardless of their physical abilities.

Importantly, the digital era has opened new avenues for inclusivity in the hospitality sector. Studies by Gretzel et al. (2015) discuss the role of technology in enhancing the inclusivity of services, particularly for diverse customer segments. Mobile apps, online platforms, and virtual concierge services can be designed to accommodate different preferences, languages, and cultural sensitivities, contributing to a more inclusive and personalized guest experience.

Recent literature underscores the significance of inclusive policies and training in shaping the hospitality industry. These initiatives not only address legal and societal expectations but also contribute to the strategic success of businesses by enhancing employee performance, customer satisfaction, and overall competitiveness. As the industry continues to evolve, the integration of inclusive practices remains essential for creating welcoming and accessible spaces for both employees and guests.

6.3.3. Variations in Inclusivity Across Establishments

In the landscape of the hospitality industry, variations in inclusivity across establishments reflect the complex interplay of organizational culture, leadership, and the industry’s response to societal expectations. Recent literature provides insights into the factors contributing to divergent levels of inclusivity and the impact on customer experiences.

Organizational culture plays a central role in shaping inclusivity within hospitality establishments. Research by Kang et al. (2019) underscores that a culture that values diversity and inclusion at its core creates an environment where employees feel supported and engaged. Variations in inclusivity can be attributed to differences in how organizational cultures prioritize and operationalize inclusivity, influencing the attitudes and behaviors of both staff and management.

Leadership within hospitality establishments emerges as a critical factor in determining the level of inclusivity. The work of Aycan et al. (2018) emphasizes that leaders who champion inclusivity set the tone for the entire organization. Establishments with leaders committed to fostering an inclusive culture are more likely to implement policies and practices that prioritize diversity, creating a ripple effect throughout the organizational hierarchy.

The industry’s response to societal expectations and trends significantly influences variations in inclusivity across establishments. Studies by Gursoy et al. (2017) highlight that hospitality businesses operating in diverse and dynamic markets may be more inclined to prioritize inclusivity as a strategic imperative. Conversely, establishments in more homogenous environments may not face the same external pressures to diversify their workforce or tailor their services to meet the needs of a diverse clientele.

Moreover, the level of inclusivity can vary based on the size and resources of the hospitality establishment. Research by Shin et al. (2019) suggests that larger establishments may have the capacity to invest in comprehensive training programs, specialized services, and resources dedicated to fostering inclusivity. Smaller establishments, on the other hand, may face limitations in terms of budget and manpower, impacting the extent to which they can implement inclusive policies and practices.

The local and cultural context within which hospitality establishments operate also contributes to variations in inclusivity. The study by Kim and Lee (2019) highlights that establishments situated in culturally diverse regions may naturally adopt more inclusive practices to cater to a heterogeneous customer base. Conversely, establishments in more homogeneous cultural settings may not perceive the same urgency to prioritize inclusivity in their operations.

Digital advancements in the hospitality industry introduce additional dimensions to variations in inclusivity. Research by Sigala (2017) discusses how technology can be leveraged to enhance accessibility and inclusivity for diverse customer segments. Establishments that strategically incorporate digital tools to accommodate different needs, preferences, and abilities may exhibit higher levels of inclusivity compared to those slow to adapt to technological advancements.

6.4. RO 4: Describing Experiences of African Perceptions Regarding Service in Post-Apartheid South Africa

Service delivery in post-apartheid South Africa has been contentious, with significant disparities in service quality and accessibility across different regions and communities. The African population, especially in rural and underprivileged urban areas, often faces inadequate service delivery, including challenges such as insufficient infrastructure and lack of access to basic services like water and electricity. These service delivery shortcomings contribute to perceptions of neglect and marginalization, reflecting a continuity of apartheid-era spatial and social divisions. The frustration and dissatisfaction arising from these challenges have led to numerous protests and public expressions of discontent, highlighting the critical need for improvement and equality in service provision (von Holdt, 2010). In the context of this study, exploring African perceptions of service in post-apartheid South Africa requires an understanding of the socio-economic dynamics that shape these experiences, divided into three critical areas: Economic Inequality, Service Delivery, and Social Cohesion and Identity.

6.4.1. Economic Inequality

Economic inequality in post-apartheid South Africa is a pervasive issue that profoundly influences the perceptions and experiences of service delivery among the African population. The entrenched economic disparities, a residue of the apartheid era, have led to a pronounced division between different racial and socio-economic groups, resulting in unequal access to essential services such as healthcare, education, and housing.

The apartheid system, which was officially dismantled in 1994, institutionalized racial segregation and economic discrimination, creating deep-rooted inequalities that persist in the post-apartheid era. Despite the end of formal apartheid, the socio-economic landscape of South Africa remains starkly divided, with a significant portion of the African population continuing to live in poverty and experiencing limited access to quality services (Statistics South Africa, 2020).

This economic divide has significant implications for service delivery in South Africa. The quality and accessibility of services such as healthcare, education, and housing are often contingent upon one’s economic status, with wealthier individuals and communities enjoying higher standards of service. This disparity is particularly evident in the healthcare sector, where private healthcare facilities, predominantly accessible to the affluent, provide a stark contrast in quality and efficiency compared to the under-resourced public healthcare system relied upon by the majority of the African population (Coovadia et al., 2009).

Education in South Africa also exemplifies the impact of economic inequality on service delivery. While the post-apartheid government has made significant strides in improving access to education, disparities in the quality of education between affluent and disadvantaged communities remain profound. Schools in economically deprived areas often suffer from inadequate infrastructure, overcrowded classrooms, and a scarcity of teaching resources, which significantly hampers the quality of education provided (Spaull, 2013).

The housing sector further reflects the economic divide’s impact on service delivery. Many South Africans, particularly in the African population, reside in informal settlements with limited access to basic services such as clean water, sanitation, and electricity. The government’s efforts to provide housing have been hampered by challenges such as resource constraints, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and corruption, exacerbating the housing crisis and contributing to widespread dissatisfaction and protests over service delivery (Turok, 2014).

Moreover, the economic inequality in South Africa is not merely a matter of material deprivation but also contributes to a sense of social injustice and marginalization among the African population. The persistent economic disparities serve as a reminder of the apartheid past and undermine the social cohesion and inclusive citizenship envisioned in the post-apartheid era. This sense of injustice is further exacerbated by perceptions of corruption and inefficiency within the government, leading to mistrust in the state’s ability and willingness to address the needs of its most disadvantaged citizens (von Holdt, 2010).

Service delivery in post-apartheid South Africa encapsulates a complex array of issues, significantly shaped by historical injustices and contemporary socio-economic disparities. The challenges faced by the African population in accessing quality services are multifaceted, spanning various sectors including healthcare, education, and basic utilities. This situation is further complicated when considering services provided by white-owned entities, such as restaurants, banks, and medical centers, where the dynamics of race, economic status, and historical privilege intersect, potentially influencing the quality and accessibility of services offered to African customers.

6.4.2. Disparities in Service Provision

In the context of South Africa, where the legacy of apartheid has left indelible marks on the socio-economic landscape, disparities in service delivery often mirror the racial and economic divides. White-owned businesses and service providers, operating within this historical and socio-economic framework, may inadvertently perpetuate these divides. For example, the location of businesses, pricing strategies, and even the level of service can reflect and reinforce existing inequalities. In areas where infrastructure is lacking, predominantly affecting African communities, the presence and quality of services from white-owned entities can be noticeably different (McDonald & Pape, 2002).

Healthcare Services

In the healthcare sector, disparities are evident in the distribution and quality of services between urban and rural areas, and between private and public healthcare facilities. Private healthcare facilities, which are often better resourced and provide higher quality care, are disproportionately owned and used by the white and affluent segments of the population. This leaves the majority of the African population reliant on underfunded and overstretched public healthcare services, exacerbating health inequalities (Coovadia et al., 2009).

Financial Services

The banking and financial services sector also reflects disparities in service provision. Historically, white-owned banks have been concentrated in urban and economically developed areas, making access to financial services more challenging for individuals in rural or impoverished areas, who are predominantly African. This lack of access to financial services hinders economic opportunities and perpetuates cycles of poverty and inequality (James & Verrest, 2015).

Hospitality and Retail Services

In the hospitality and retail sectors, experiences of discrimination and unequal treatment in white-owned establishments, such as restaurants and shops, have been reported. These experiences range from overt racial discrimination to more subtle forms of exclusion, such as assumptions about purchasing power based on race. Such incidents not only reflect individual prejudices but also point to systemic issues within the service industry that can alienate African customers and reinforce feelings of marginalization (Crush & Ramachandran, 2014).

Addressing Service Delivery Challenges

Addressing the challenges of service delivery in post-apartheid South Africa, especially in the context of white-owned entities, requires a multifaceted approach. Policies aimed at redressing historical inequities, promoting equal access to services, and ensuring non-discriminatory practices within the private sector are essential. Moreover, initiatives to improve infrastructure, particularly in underserved areas, and to enhance the capacity and quality of public services, can help bridge the gap in service delivery. Encouraging corporate social responsibility and community engagement among white-owned businesses can also play a role in fostering more inclusive service provision (Pillay, 2016).

6.4.3. Social Cohesion and Identity

The post-apartheid era in South Africa has been characterized by efforts to foster social cohesion and rebuild a national identity that transcends racial and economic divides. The apartheid regime’s policies of racial segregation and economic discrimination left a legacy of division and mistrust among the country’s diverse communities. In this context, the provision and perception of public services are not merely practical concerns but are imbued with symbolic significance in the broader project of nation-building and social reconciliation.

The struggle against apartheid was not only a fight for political freedom but also a quest for dignity, equality, and recognition for the majority of South Africans who had been marginalized and dehumanized under the apartheid system. In the post-apartheid context, access to quality services is emblematic of the broader aspirations for a just and equitable society. For many in the African population, the ability to access quality healthcare, education, and housing is seen as a reaffirmation of their rights and citizenship in the new South Africa. These services are perceived as tangible manifestations of the promises of freedom and equality that were at the heart of the anti-apartheid struggle (Gibson, 2004).

Equitable service delivery is crucial for fostering social cohesion and building a shared national identity. The disparities in service provision that mirror the socio-economic inequalities inherited from the apartheid era serve to perpetuate feelings of exclusion and alienation among disadvantaged communities. The perception that the state is failing to provide adequately for the needs of all its citizens can undermine trust in public institutions and erode the social fabric necessary for a cohesive society (Mattes, 2002).

Efforts to improve service delivery in underprivileged areas, therefore, have significance beyond the immediate benefits of the services themselves. They are part of a broader endeavor to heal the divisions of the past and weave a new social tapestry that includes all South Africans. When public services are delivered equitably and efficiently, they can act as powerful symbols of inclusion and respect, reinforcing the idea that every citizen, regardless of race or economic status, is valued and has a place in the national community (Lefko-Everett, 2012).

However, the path to social cohesion through equitable service delivery is fraught with challenges. The legacy of apartheid’s spatial planning continues to impact the distribution of services, with historically disadvantaged areas often facing significant infrastructure deficits. Moreover, issues of corruption and inefficiency within public service delivery mechanisms can further exacerbate feelings of disillusionment and mistrust among citizens, particularly those who are most in need of support (von Holdt, 2010).

Addressing these challenges requires a committed and multifaceted approach. It involves not only significant investment in physical infrastructure and human resources but also a concerted effort to foster transparency, accountability, and community participation in the design and delivery of public services. Engaging communities in the process of service delivery can help to rebuild trust in public institutions and reinforce the sense of agency and inclusion among citizens (Booysen, 2007).

In post-apartheid South Africa, the perceptions and experiences of service delivery are deeply intertwined with broader issues of social cohesion and national identity. Equitable and efficient public services are central to the project of building a united and inclusive society. By addressing the legacies of apartheid in the provision of services, South Africa can continue to move towards a future where all citizens feel valued, recognized, and included in the national narrative.

6.5. Summary

The experiences and perceptions of service among the African population in post-apartheid South Africa are shaped by a complex interplay of economic inequality, service delivery challenges, and the ongoing process of social cohesion and identity formation. Addressing these issues requires a concerted effort to bridge service provision gaps, dismantle economic disparities, and foster a sense of belonging and inclusivity among all South Africans.

Economic inequality in post-apartheid South Africa has a profound impact on the perceptions and experiences of service delivery among the African population. The legacy of apartheid’s economic disparities continues to shape the socio-economic landscape, resulting in unequal access to essential services and contributing to a sense of injustice and marginalization. Addressing these disparities requires a multifaceted approach that includes targeted interventions to improve the quality and accessibility of services in disadvantaged communities, along with broader economic reforms to reduce inequality and foster a more inclusive society.

6. Methods

6.1. Introduction

In the realm of evidence synthesis, methodological frameworks play a crucial role in structuring the inquiry process and ensuring rigor in the analysis of existing literature. The SPIDER framework (Cooke, et al., 2012) and the SALSA analytical framework (Samnani, et al., 2017), as employed by Maria J. Grant and Andrew Booth in their seminal work “A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies” (2009), provide valuable tools for researchers engaged in qualitative evidence synthesis (Grant & Booth, 2009).

The SPIDER framework, an acronym for Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type, offers a systematic approach to formulating specific and refined research questions in qualitative evidence synthesis. By delineating key elements such as the target sample, phenomenon of interest, research design, evaluation, and type, SPIDER ensures a structured and comprehensive framing of the research question. This methodological clarity contributes to the precision and relevance of the qualitative evidence synthesis process (Cooke, et al., 2012).

The SALSA framework, encompassing Search, AppraisaL, Synthesis, and Analysis, serves as a simple yet effective analytical tool tailored for examining various review types. It offers a structured approach to each phase of the evidence synthesis process (Samnani, et al., 2017). The Search phase involves systematically retrieving relevant literature, the Appraisal phase focuses on critically evaluating the quality of the identified studies, the Synthesis phase entails integrating findings across studies, and the Analysis phase involves interpreting and drawing conclusions from the synthesized evidence. SALSA’s simplicity and comprehensiveness make it a valuable guide for researchers navigating the complexities of qualitative evidence synthesis (Grant & Booth, 2009).

Grant and Booth’s work in developing a typology of reviews further enriches the landscape of evidence synthesis methodologies. Their analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies provides researchers with a comprehensive overview of diverse approaches to reviewing evidence, ranging from systematic reviews and meta-analyses to scoping reviews and realist reviews. This typology not only serves as a reference guide for researchers selecting an appropriate review type but also contributes to the ongoing discourse on methodological diversity within evidence synthesis (Grant & Booth, 2009)

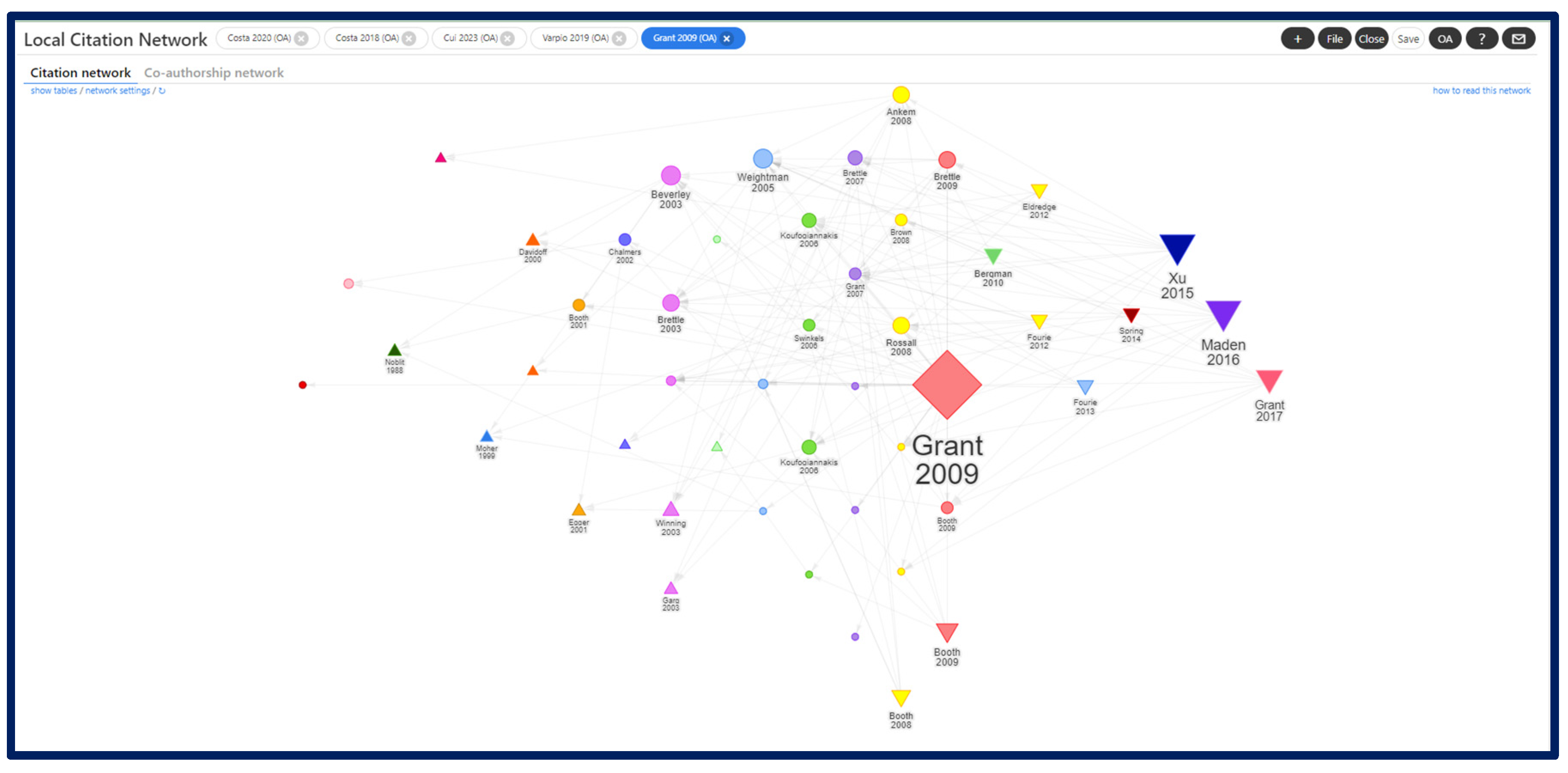

Figure 1. Thus, the framework for method used for research design, namely, QES, was hinged upon the seminal work of Grant and Booth (2009).

6.2. Research Design

A qualitative systematic review serves as a method for comparing and integrating findings from various qualitative studies, aiming to accumulate knowledge that may lead to the development of new theories, overarching narratives, wider generalizations, or interpretative translations (Grant, 2009; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007). This approach focuses on identifying themes or constructs within and across individual qualitative studies, with the goal of broadening the understanding of a specific phenomenon. Unlike meta-analysis, the objective is interpretative rather than aggregative, emphasizing the interpretation of findings rather than statistical combination (Chalmers, et al., 2002).

The term “qualitative systematic review” has caused confusion, primarily stemming from historical associations with systematic reviews where meta-analysis is not feasible. The Cochrane Collaboration’s Qualitative Research Methods Group advocates for the use of “qualitative evidence synthesis” to mitigate ambiguity in terminology. Alternative terms encountered include “qualitative meta-synthesis” and “meta-ethnography,” the latter being somewhat misleading as it refers to a method adaptable to interpreting various types of qualitative research, not limited to ethnographies (Toye, et al., 2014; Noblit & Hare, 1988).

Qualitative systematic reviews offer strengths in exploring barriers and facilitators to service delivery, understanding user views, investigating perceptions of new roles, and informing service prioritization when evidence on effectiveness is inconclusive. This type of review complements research evidence with user-reported and practitioner-observed considerations, potentially offering more powerful insights than isolated comments from local questionnaires or surveys.

However, methods for qualitative systematic reviews are still evolving, leading to considerable debate about when specific methods or approaches are appropriate. Debates include the necessity of comprehensive search strategies versus a more selective approach for a holistic interpretation of a phenomenon. The ongoing discussions revolve around whether the dominant model for qualitative evidence synthesis should align with classic systematic review methods or adapt concepts from primary qualitative research. Despite these debates, emerging guidance from sources such as the Cochrane Collaboration’s handbook and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination methodologies is gradually moving towards greater consensus.

6.3. Research Process

Based on the works of Costa (2024,2022,2020), the review process outlined will cover the following seven steps:

6.3.1. Defining the Review Question

Establishing a clear and focused question that the review aims to answer. This step is crucial for guiding the entire review process, including literature search, selection criteria, and synthesis approach.

6.3.2. Developing a Protocol

Before starting the review, a detailed plan or protocol is developed, outlining the methods that will be used throughout the review process. This includes search strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction methods, and plans for data synthesis and analysis. This document is a full representation of the review protocol to be used. This review will be registered with the Open Science Framework Registries.

6.3.3. Conducting a Systematic Search

A comprehensive search of relevant databases and sources will be conducted to identify studies that address the review question. This step involves using carefully chosen keywords and search terms to ensure that relevant literature is not missed. The search will be conducted on Harzing and Publish repository, an artificial intelligence-driven platform which is a compendium of databases such as Crossref, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, Open Alex, Semantic Scholar and PubMed(Harzing, 2022).

6.3.4. Screening and Selecting Studies

All identified records will be screened based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to select studies that are relevant to the review question. This usually involves a two-stage process of screening titles and abstracts followed by a full-text review(Xiao & Watson, 2017).

6.3.5. Appraising Study Quality

The methodological quality and relevance of the selected studies will be assessed to determine the trustworthiness of their findings. In systematic reviews, various appraisal tools can be used depending on the types of studies included in the review. However, in this qualitative evidence synthesis, PRISMA Workflow (Moher, et al., 2009), CASP (Long, et al., 2020) and ENTREQ (Tong, et al., 2012) will be used.

6.3.6. Extracting and Synthesizing Data

Relevant data are extracted from the included studies, and a synthesis is conducted to integrate the findings. In a qualitative evidence synthesis, this may involve thematic synthesis, meta-ethnography, or other methods suitable for handling qualitative data. In this particular study, thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, 2008) will be used to generate themes that are aligned to the research objectives of this inquiry. The COSTAQDA, a cloud-based qualitative data analysis software that is suitable for literature-based inquiry will be used (Ntsobi & Costa, 2022;Qwabe, 2021).

6.3.7. Reporting and Dissemination

The findings of the review will be compiled into a comprehensive report, which will then disseminated to relevant stakeholders within policy-making and academic circles. Furthermore, dissemination of findings will also be published in recognised journals. This report should include a detailed account of the review methods, findings, limitations, and implications for practice and research.

7. The Importance of the Study

This study holds significant importance in both academic and practical realms, offering critical insights into the ongoing challenges and opportunities within the hospitality industry in post-apartheid South Africa. By focusing on the experiences of African customers in white-owned restaurants and hotels, the research sheds light on the nuanced interplay between historical legacies, societal dynamics, and economic factors that continue to shape customer-service provider interactions in this context. The importance of this study can be articulated through several key dimensions:

7.1. Social Reconciliation and Transformation

The study contributes to the broader discourse on racial reconciliation and social transformation in South Africa, a country still grappling with the remnants of apartheid. Understanding the dynamics within the hospitality industry serves as a microcosm for examining the progress towards a more inclusive and equitable society, highlighting both strides and stumbling blocks in the journey towards social cohesion.

7.2. Industry Practices and Policy Implications

Insights derived from this research can inform industry practices and policy formulation, guiding stakeholders in developing strategies that promote inclusivity and sensitivity towards the diverse clientele they serve. This is particularly relevant for training programs, service protocols, and corporate social responsibility initiatives aimed at fostering environments that are welcoming to all customers, irrespective of racial or ethnic backgrounds.

7.3. Enhancing Customer Experience

At the heart of the hospitality industry is the commitment to delivering exceptional customer experiences. This study underscores the importance of understanding the specific expectations and challenges faced by African customers in white-owned establishments, thereby enabling service providers to tailor their offerings more effectively. Enhancing the customer experience for this demographic not only contributes to business success but also reflects a genuine commitment to embracing South Africa’s rich cultural diversity.

7.4. Academic Contribution

From an academic perspective, the study adds to the body of knowledge on post-apartheid societal dynamics, particularly within the context of the service industry. By employing a qualitative systematic review approach, the research enriches the literature with empirical evidence and lived experiences, offering a grounded understanding of the intricate factors influencing service interactions in racially and culturally diverse settings.

7.5. Promoting Economic Inclusion

The hospitality industry is a significant contributor to South Africa’s economy, offering numerous employment and entrepreneurial opportunities. This study highlights the importance of creating an industry that is not only economically vibrant but also socially inclusive. By addressing the challenges faced by African customers in white-owned establishments, the industry can contribute to breaking down economic barriers and promoting broader participation in the tourism and hospitality sector.

7.6. Global Relevance

While the study is centered on post-apartheid South Africa, its findings have broader implications for understanding racial dynamics in hospitality settings worldwide. In an increasingly globalized world, the lessons learned from this research can offer valuable insights for other regions confronting similar issues of historical discrimination and striving to create more inclusive service environments.

In sum, the importance of this study lies in its potential to influence a range of stakeholders, from policymakers and industry practitioners to academics and the wider society, driving forward the agenda for a hospitality industry that truly embodies the values of inclusivity, respect, and equality.

8. Conclusion

In anticipation of the forthcoming research, this study protocol sets the stage for a critical examination of the experiences of African customers in white-owned restaurants and hotels in post-apartheid South Africa. By delving into the nuanced interactions between service providers and African patrons, the study aims to uncover the underlying dynamics that continue to shape these encounters in the shadow of a historically divided society.

The importance of this research lies not only in its potential to highlight persistent challenges and inequities within the hospitality industry but also in its capacity to identify pathways towards more inclusive and equitable service practices. As South Africa continues to grapple with the legacies of apartheid, understanding the current state of racial dynamics within such a customer-facing industry offers invaluable insights into broader societal trends and challenges.

The findings of this study are expected to contribute to a body of knowledge that informs both academic discourse and practical interventions. For industry practitioners, the insights gained may serve as a foundation for developing training programs, policies, and practices that actively promote inclusivity and cultural sensitivity. For policymakers and social change advocates, the research could provide evidence to support initiatives aimed at fostering racial reconciliation and social cohesion in post-apartheid South Africa.

Ultimately, this study aims to not only document and analyze the current state of affairs but also to inspire action towards a more inclusive and understanding society, where the hospitality industry serves as a microcosm of progress and unity in diversity. As such, the conclusion of this study protocol underscores the importance of the upcoming research in contributing to the ongoing dialogue around racial equity, social justice, and the transformative potential of the hospitality industry in post-apartheid South Africa.

About Authors:

-

King Costa is the co-founder of the Global Centre for Academic Research and Costa Research Institute. He is the author of the cloud-based COSTAQDA software, which provides simple intuitive approach to qualitative data analysis and appraisal of literature review. He was the chairperson of the South African chapter of the 8th World Conference on Qualitative Research and is the founder of the Association of Research Methodologists. He has authored a number of papers, book chapters and teaching materials in Qualitative Evidence Synthesis and Mixed Methods Research. He is a member of the Editorial Board of New Trends in Qualitative Research – A Scielo and Scopus indexed international journal.

Contact: costak@researchglobal.net

-

Letlhogonolo Mfolo is a Research Assistant and Chief of Staff in Prof King Costa’s office. He is a current student of the Programme in Research Methods offered at Postgraduate Level in Association with South Valley University. He is also an accredited trainer of the COSTAQDA software. His passion is on Qualitative Systematic Reviews and Qualitative Data Analysis using CAQDAS. He has presented, published papers and attended academic conferences and seminars in South Africa, Portugal and the Philippines.

Contact: mfolol@researchglobal.net

References

- Adams, H., 2017. The Roots of African Hostility in South Africa. Foreign Affairs, 96(2), pp. 126-132.

- Addie, J. P., Ball, A. D. & Adams, A. E., 2019. Consumer identity and marketing: Current knowledge and future directions. Journal of Business Research, Volume 96, pp. 208-225.

- Anaza, N. A., Green, T. & Chapa, S., 2021. The impact of consumer identity on brand engagement. Journal of Business Research, Volume 130, pp. 731-740.

- Anaza, N. A., Hua, N. & Gao, L., 2018. Cultural influences on consumer brand identification and outcomes. Journal of Business Research, Volume 88, pp. 81-89.

- Aycan, Z. K. R. N. M. M. Y. K. D. J. S. G. & Varma, A., 2018. Culture and leadership across the world: The GLOBE book of in-depth studies of 25 societies. s.l.:Routledge.

- Berry, L. L., 2000. Cultivating service brand equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), pp. 128-137.

- Bhana, D. & Hofmeyr, J., 2016. Imagining the City: Memories and Cultures in Cape Town. Pretoria: HSRC Press.

- Boonzaaier, C. & de Lange, N., 2019. Mediating visual stories of nationhood on social media: Reflections on the state of post-apartheid South Africa. Communication Research Reports. Communication Research Reports, 36(2), pp. 155-165.

- Booysen, S., 2007. With the Ballot and the Brick: The Politics of Attaining Service Delivery. Progress in Development Studies, 7(1), pp. 21-32.

- Brotheridge, C. & Lee, R. T., 2003. Development and validation of the Emotional Labour Scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(3), pp. 365-379. [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, I., Hedges, L. V. & Cooper, H., 2002. A brief history of research synthesis. Evaluation and the Health Professions, Volume 25, p. 12–37. [CrossRef]

- Choi, T. Y. & Chu, R., 2011. Determinants of hotel guests’ satisfaction and repeat patronage in the Hong Kong hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(2), pp. 552-567. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A., Smith, D. & Booth, A., 2012. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), p. 1435–1443. [CrossRef]

- Coovadia, H. et al., 2009. The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. The Lancet, Volume 374, pp. 817-834. [CrossRef]

- Costa, K., 2020. The Cause of Panic at the Outbreak of COVID-19 in South Africa – A Comparative Analysis with Similar Outbreak in China and New York. SSRN.

- Costa, K. et al., 2024. Study Protocol of “Exploring the Interplay between Family Responsibilities, Personal Vulnerabilities, and Motivational Theories in the Publishing Endeavours of Women Scholars: A Qualitative Evidenc. Preprints 2024, pp. 1-11.

- Costa, K. & Ntsobi, M., 2022. The Role and Potential of Information Communication Technology (ICT) in Early Childhood Education in South Africa: A Theoretical Perspective. In: A. Costa, A. Moreira, M. Sánchez-Gómez & S. Wa-Mbaleka, eds. Computer Supported Qualitative Research. WCQR 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 466. Cham: Springer, pp. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, R. & Stefancic, J., 2017. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. s.l.:New York University Press.

- Essid, Y., 2018. Apartheid legacies and civic identities in post-apartheid South Africa: An analysis of ‘popular’ films. Critical Sociology, 44(6), 44(6), pp. 987-1005.

- Gibson, L., 2004. Overcoming Apartheid: Can Truth Reconcile a Divided Nation?. s.l.:Russell Sage Foundation.

- Grant, M. J. B. A., 2009. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), pp. 91-108. [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., Sigala, M., Xiang, Z. & Koo, C., 2015. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electronic Markets, 25(3), pp. 179-188. [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., Sigala, M., Xiang, Z. & Koo, C., 2015. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electronic Markets, 25(3), pp. 179-188.

- Gursoy, D., Chi, C. G. Q. & Lu, L., 2017. Antecedents and outcomes of hotel employees’ discrimination against guests. Tourism Management, Volume 58, pp. 148-157.

- Harrington, R. J. & Ottenbacher, M. C., 2011. The role of online brand communities in fostering customer engagement: A conceptual framework. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 20(1), pp. 31-40.

- Harris, A. & Reynolds, H., 2013. Apartheid and social capital in post-apartheid South Africa: The impacts of forced segregation on collective action in a former township. African Affairs, 112(449), pp. 48-69.