Submitted:

06 March 2024

Posted:

07 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

1. An overview of Atropa belladonna’s

1.1. Genus Atropa belladonna (Table 1)

1.2. Atropa belladonna Morphology:

1.3. Medicinal Uses of Atropa belladonna:

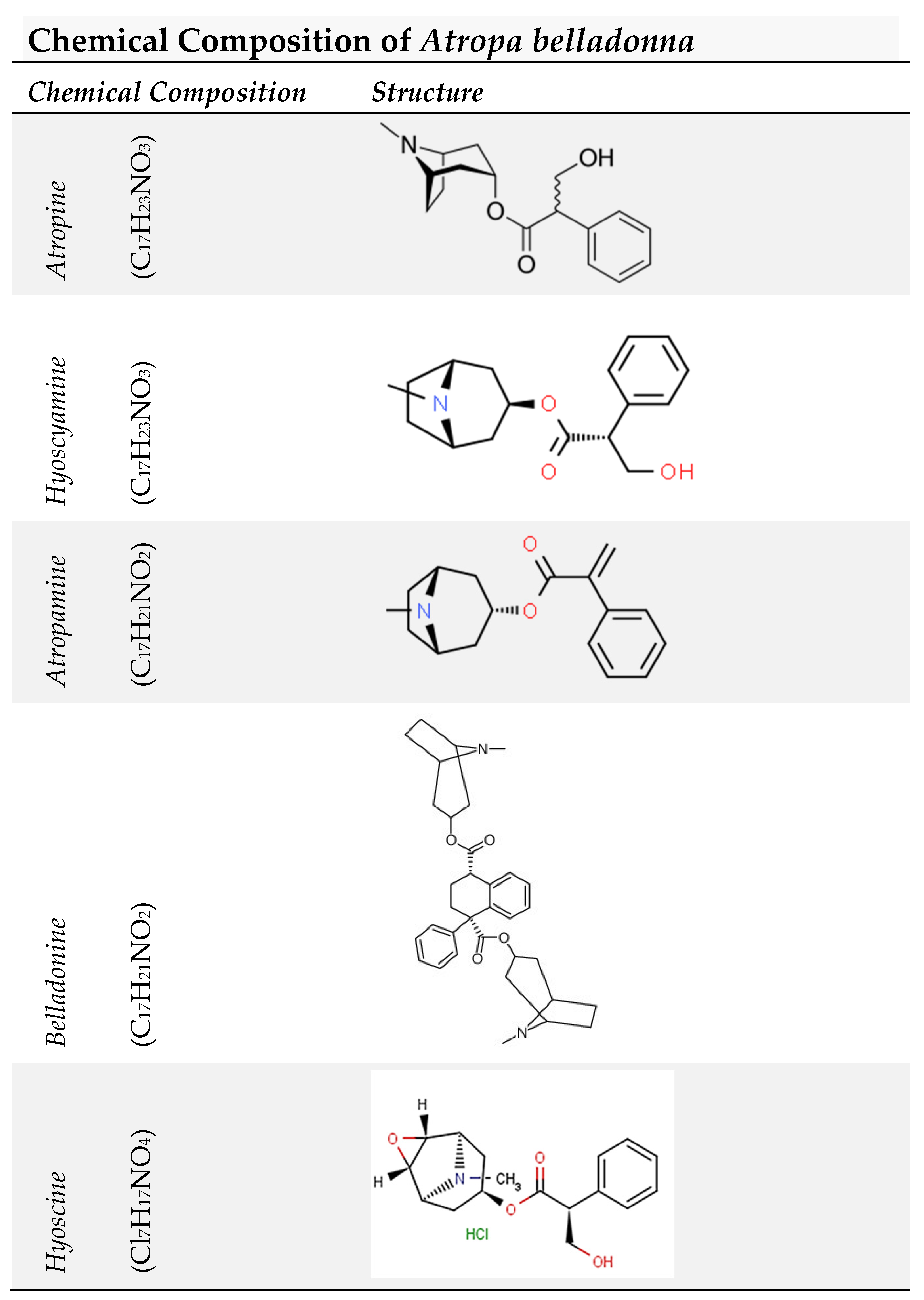

1.5. Composition and Properties of Atropa belladonna Species

Chemical Composition

Species Related to Atropa belladonna and Adulterants

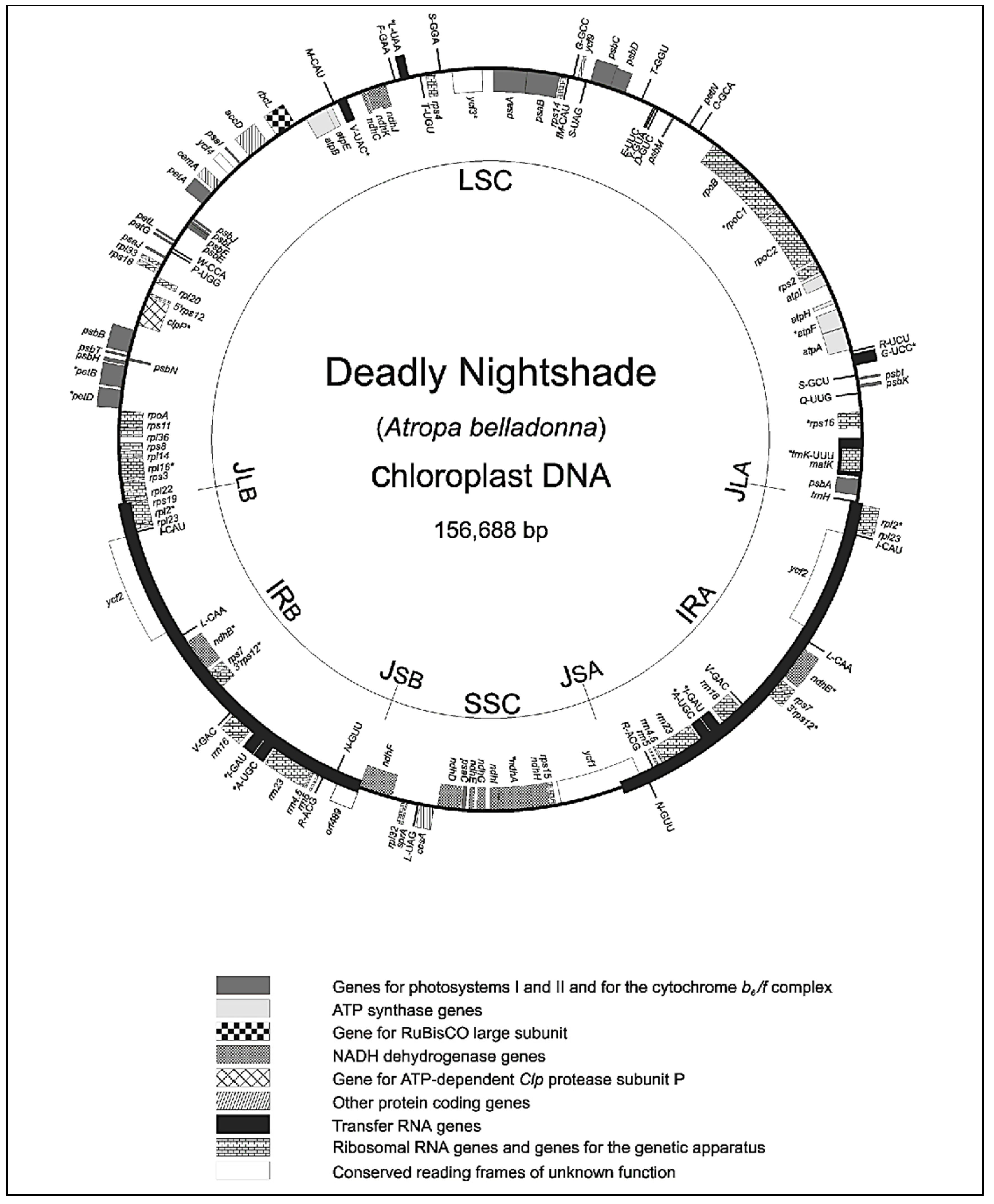

2. Detection of Medicinal Plant DNA Barcoding

2.1. Definition and Goals behind DNA Barcoding

2.2. Unique Plant DNA Barcoding Requirement

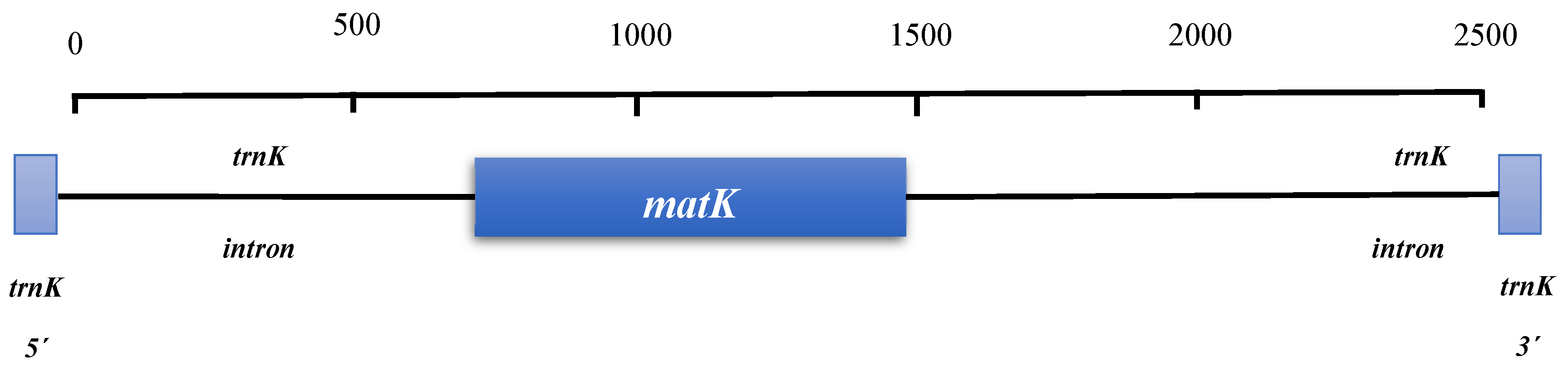

2.3. matK Locus

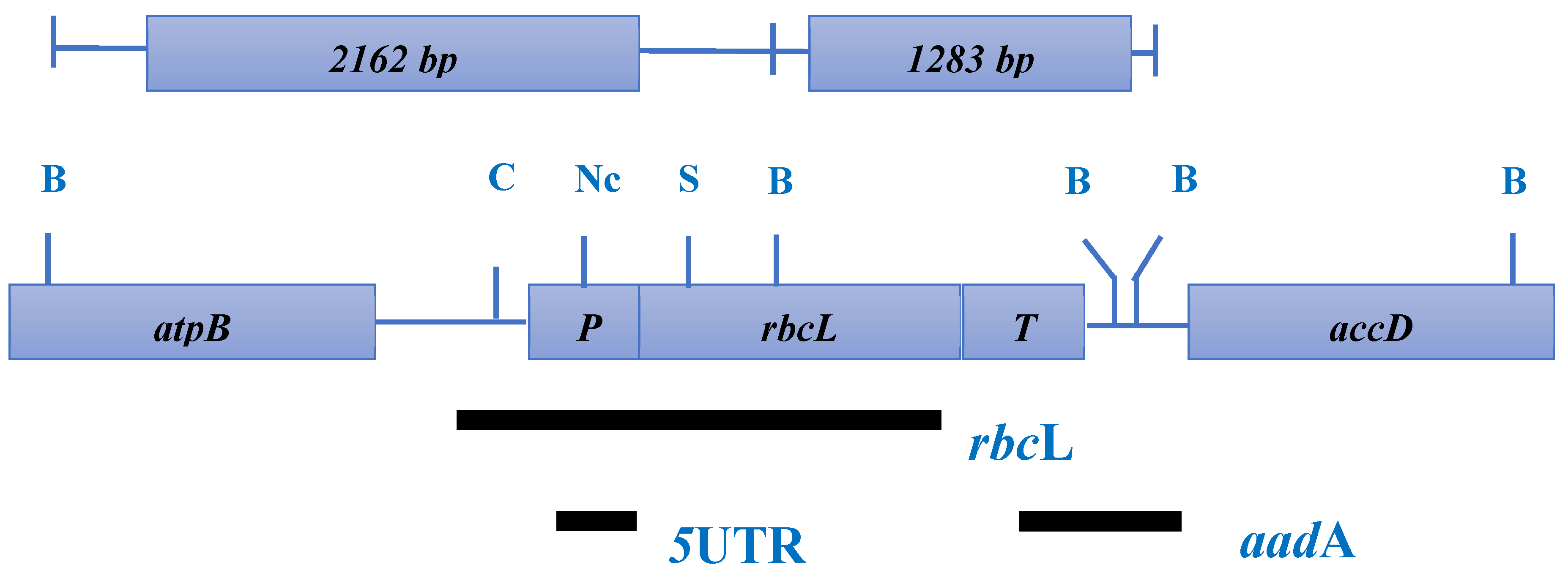

2.4. rbcL Locus

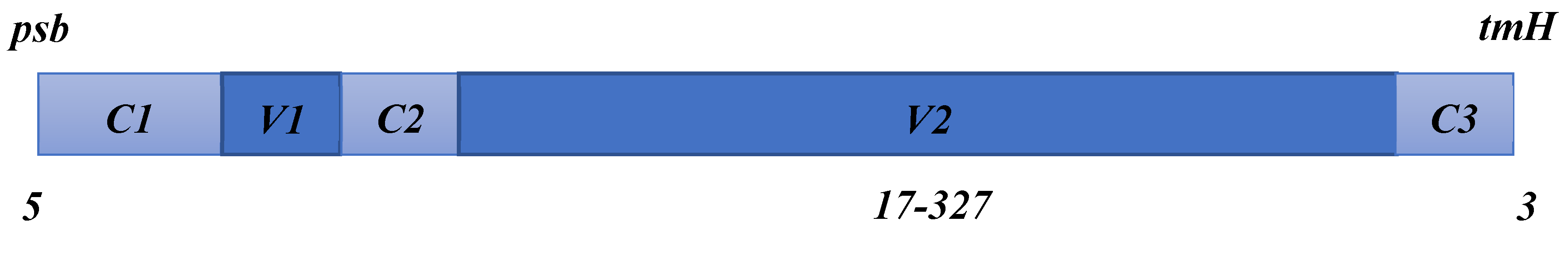

2.5. The trnH-psbA Locus

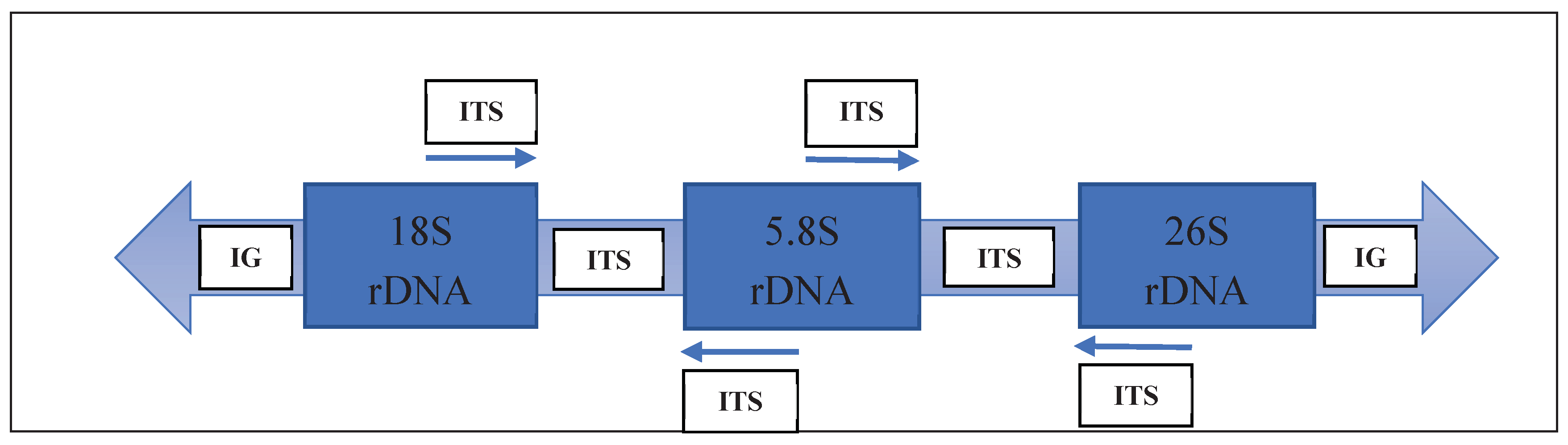

2.6. The ITS Locus

2.6. Combination of Barcodes for Plant Identification.

IV. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kennedy, D. O. (2014). Plants and the human brain. Oxford University Press.

- Blumenthal, M. , Goldberg, A., & Brinckmann, J. (Eds.). (2000). Herbal medicine: Expanded Commission E monographs. Integrative Medicine Communications.

- Frohne, D. , & Pfänder, H. J. (2005). A colour atlas of poisonous plants: A handbook for pharmacists, doctors, toxicologists, and biologists. Manson Publishing.

- Schep, L. J., Slaughter, R. J., & Vale, J. A. (2009). Pharmacological and toxicological properties of Atropa belladonna L. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research, 39(2), 145-147. [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, S. , & Lavoie, M. (2015). Plant toxins in poisonings and intoxications. In J. H. Duffield, G. P. Bailey, & T. S. Hovda (Eds.), Veterinary toxicology: Basic and clinical principles (3rd ed., pp. 457-476). Academic Press.

- Jones, J. R. (2005). Deadly nightshade. In Poisonous plants of Pennsylvania and their toxins (2nd ed., pp. 44-45). Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture.

- Peterson, L. (2020). Solanum nigrum L. In M. L. Gargiullo & B. Magnuson (Eds.), Flora of North America North of Mexico (Vol. 7, pp. 326-331). Oxford University Press.

- Martin, R. F. (2004). Atropa belladonna L. In G. W. Argus (Ed.), Flora of North America North of Mexico (Vol. 7, pp. 75-78). Oxford University Press.

- Nithaniyal, S., Vassou, S. L., Poovitha, S., & Jayabalan, M. (2017). DNA barcoding as a reliable method for the authentication of medicinal plants used in the preparation of herbal products. Journal of Herbal Medicine, 9, 45-51. [CrossRef]

- CBOL Plant Working Group. (2009). A DNA barcode for land plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(31), 12794-12797. [CrossRef]

- Svensson, B. M. , & Tyler, T. (2013). Flora of Skne: The vascular plants of Skne, Sweden (2nd ed.). Sknes Flora Frlag.

- USDA, NRCS. (2021). Plants Profile for Atropa belladonna L. Retrieved from https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?

- Lee, T. (2007). Flora of China: Solanaceae. In Z. Y. Wu, P. H. Raven, & D. Y. Hong (Eds.), Flora of China (Vol. 17, pp. 287-292). Science Press/Missouri Botanical Garden Press.

- Zárate, R. , el Jaber-Vazdekis, N., Medina, M., & Ravelo, Á. G. (2006). Tropane alkaloid profile of Atropa belladonna L. at different growth stages. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 54(6), 2048-2052. [CrossRef]

- Riddle, J. M. (2016). Atropa belladonna. In J. Riddle (Ed.), Dioscorides on pharmacy and medicine (pp. 201-203). University of Texas Press.

- Hahn, R. A. (2002). The nocebo phenomenon: Concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Preventive Medicine, 34(6), 639-648. [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E. , & Pittler, M. H. (2000). Efficacy of homeopathic arnica: A systematic review of placebo-controlled clinical trials. Archives of Surgery, 135(11), 1321-1326. [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E. , & Pittler, M. H. (2000). Efficacy of ginger for nausea and vomiting: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 84(3), 367-371. [CrossRef]

- Adams, R. P. (2007). Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (4th ed.). Allured Publishing Corporation.

- Perry, L. M. , & Metzger, J. (1980). Medicinal plants of East and Southeast Asia: Attributed properties and uses. MIT Press.

- Bisset, N. G. (1994). Herbal drugs and phytopharmaceuticals (1st ed.). CRC Press.

- Rätsch, C. (2005). The encyclopedia of psychoactive plants: Ethnopharmacology and its applications (3rd ed.). Park Street Press.

- Langford, N. J., & Boobis, A. R. (2002). Belladonna poisoning. Toxicological Reviews, 21(2), 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Bismuth, C. , & Hall, A. H. (2009). Anticholinergic syndrome. In A. H. Hall, L. J. Rumack, & R. L. Clark (Eds.), Antidote for poisoning by organophosphorus pesticides (pp. 57-59). CRC Press.

- Gardner, J. R. (1965). The use of alkaloids of Belladonna to counteract the toxic effects of parathion and other organophosphorus insecticides. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 250(2), 173-178. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, V. E. , Brady, L. R., & Robbers, J. E. (1988). Pharmacognosy (9th ed.). Lea & Febiger.

- Kruis, W., Fric, P., Pokrotnieks, J., Lukás, M., Fixa, B., Kascák, M., ... & Schreiber, I. (2004). Maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis with the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is as effective as with standard mesalazine. Gut, 53(11), 1617-1623. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, G. R. , Hanauer, S. B., Sandborn, W. J., & Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. (2009). Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 104(2), 465-483. [CrossRef]

- Maxton, D.G.; Whorwell, P.J. The treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with lorazepam, hyoscine butylbromide, and ispaghula husk. Br. J. Clin. Pract. 1979, 33, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, E. M. M. (2016). Gastrointestinal motility disorders in the elderly. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, 45(3), 405-418. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, G.A.; Schaefers, M.; Nilaver, G. A comparison of the effect of Bellergal, an extract of Belladonna, Hedera helix and Rhododendron ponticum, on menopausal symptoms. Minerva Ginecol. 1983, 35, 443–446. [Google Scholar]

- Stearns, V. , Beebe, K. L., Iyengar, M., Dube, E., Paroxetine Study Group, & Gomez, H. L. (2003). Paroxetine controlled release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 289(21), 2827-2834. [CrossRef]

- Wiffen, P. J. , McQuay, H. J., & Moore, R. A. (2017). Obstructed labour: Medical interventions for associated short-term complications in women undergoing caesarean section. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(7), CD004749. [CrossRef]

- Min, S. , & Gallardo-Casero, J. M. (2013). The effects of Chinese herbs on bronchial asthma: A review of literature. Chinese Medicine, 4(3), 99-107. [CrossRef]

- Tabarki, B. , Al-Shafi, A., & Abu Laban, A. (2008). The impact of belladonna tincture as a pre-anesthetic medication on the pediatric patient with difficult airways. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 20(7), 522-526. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, D. E. , Aaron, S., Bourbeau, J., Hernandez, P., Marciniuk, D. D., & Balter, M. (2017). Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Canadian Respiratory Journal, 14(Suppl B), 5B-32B. [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.G.; Knoedler, C.H. The treatment of vascular headache: Clinical experiences with belladonna alkaloids-phenobarbital-ergotamine combinations. J. Kans. Med. Soc. 1957, 58, 243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Muñoz, G. , Placencio-Hickok, V. R., Hernández-Muñoz, J. M., Contreras-Ochoa, C. O., & Del Valle-Martinez, L. M. (1990). The treatment of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) with a standardized mixture of Ginkgo biloba and Belladonna extracts. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation, 30(2), 113-117. [CrossRef]

- Lorton, D. , & Bellinger, D. L. (2016). Molecular mechanisms underlying β-adrenergic receptor-mediated cross-talk between sympathetic neurons and immune cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(5), 638. [CrossRef]

- Hatton, F., & Apte, S. (2018). The pharmacological management of morning sickness in pregnancy. Australian Prescriber, 41(4), 112-117. [CrossRef]

- Demiris, G. , Tsatalou, E. G., & Schulpis, K. H. (1993). Anxiety in patients with digestive problems: Its prevalence and the effectiveness of a psychotropic treatment. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 37(3), 301-306. [CrossRef]

- Zeman, J., Kvetina, J., & Pintova, J. (1970). Atropine and Librium in urological radiography. Journal of Urology, 103(5), 616-621. [CrossRef]

- Tschirch, A. , & Rohde, A. (1922). The constituents of the belladonna root. In A. Tschirch & A. Rohde (Eds.), The chemistry of plant products (Vol. 2, pp. 370-377). Macmillan Publishers.

- Pesci, A. About atropamine. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1882, 12, 317–319. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. (n.d.). Scopolia japonica Maximowicz. In H. G. A. Engler & K. Prantl (Eds.), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien nebst ihren Gattungen und wichtigeren Arten, insbesondere den Nutzpflanzen (Vol. 4, 2, pp. 277-278).

- Duckworth, D. (n.d.). On the mydriatic effects of scopoline, duboisine, and hyoscine, with special reference to the differential action of these drugs. British Medical Journal, 1(1439), 437-440. [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P. D. N., Cywinska, A., Ball, S. L., & deWaard, J. R. (2003). Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proceedings. Biological Sciences, 270(1512), 313-321. [CrossRef]

- Jaakola, L., Pirttilä, A. M., Halonen, M., & Hohtola, A. (2007). Isolation of high quality DNA for genetic studies of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) and other Vaccinium species. Molecular Ecology Notes, 7(6), 1261-1264. [CrossRef]

- ian, H., Wang, J., Yu, J., & Chen, X. (2012). Identification of roasted tea varieties using DNA barcoding. Food Research International, 48(1), 491-496. [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, S. , Stefanaki, A., Tezcan, M., Bozdogan, B., & Goudet, J. (2014). Systematic biology in Europe: The EMBO-sponsored European conference on the barcoding of arthropods. Ecological Research, 29(6), 1159-1162. [CrossRef]

- Bruni, I., De Mattia, F., Galimberti, A., Galasso, G., & Banfi, E. (2010). Identification of poisonous plants by DNA barcoding approach. International Journal of Legal Medicine, 124(6), 595-603. [CrossRef]

- De Mattia, F., Bruni, I., Galimberti, A., Cattaneo, F., Casiraghi, M., Labra, M., & Savadori, P. (2011). A comparative study of different DNA barcoding markers for the identification of some members of Lamiaceae. Food Research International, 44(3), 693-702. [CrossRef]

- Cornara, L., La Rocca, A., Marsili, S., & Mariotti, M. G. (2013). Traditional uses of plants in the Eastern Riviera (Liguria, Italy). Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 146(2), 659-668. [CrossRef]

- Kool, A., de Boer, H. J., Krüger, Å., Rydberg, A., Abbad, A., Björk, L., Martin, G., et al. (2013). Molecular identification of commercialized medicinal plants in southern Morocco. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e60677. [CrossRef]

- Newmaster, S. G. , Grguric, M., Shanmughanandhan, D., Ramalingam, S., & Ragupathy, S. (2013). DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products. BMC Medicine, 11, 222. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L. J., Boilard, S. M., & Eagle, S. H. C. (2012). DNA barcodes for routine identification of medicinal plants in the Canadian marketplace. Genome, 55(3), 192-200. 5. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. J. (2016). Barcoding of Plant (RbcL, MatK) and Animal (CO1, 16S) Genes for the Authentication of Traditional Korean Medicine. Genomics & Informatics, 14(4), 196-200. [CrossRef]

- Kress, W. J., Erickson, D. L., Jones, F. A., Swenson, N. G., Perez, R., Sanjur, O., & Bermingham, E. (2009). Plant DNA barcodes and a community phylogeny of a tropical forest dynamics plot in Panama. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(44), 18621-18626. [CrossRef]

- Erickson, D. L. , & Kress, W. J. (2008). Assessing phylogenetic relationships of the Orchidaceae with DNA-barcoding. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 44(2), 1032-1040. [CrossRef]

- Jian, H. , et al. (2014). Can DNA Barcoding of Plant Material in Holistic Approach Make a Routine Contribution for Adulteration Control of Chinese Medicines? BioMed Research International, 2014, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- CBOL Plant Working Group. (2009). A DNA barcode for land plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(31), 12794-12797. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Yao, H., Han, J., Liu, C., Song, J., Shi, L., & Zhu, Y. (2010). Validation of the ITS2 Region as a Novel DNA Barcode for Identifying Medicinal Plant Species. PLoS ONE, 5(1), e8613. [CrossRef]

- Kress, W. J. , Erickson, D. L., & Jones, F. A. (2009). DNA barcodes: Genes, genomics, and bioinformatics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(Supplement 2), 19675-19676. [CrossRef]

- Chase, M. W. , Salamin, N., Wilkinson, M., Dunwell, J. M., Kesanakurthi, R. P., Haider, N., & Savolainen, V. (2005). Land plants and DNA barcodes: Short-term and long-term goals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 360(1462), 1889-1895. [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, P. M., Graham, S. W., & Little, D. P. (2011). Choosing and using a plant DNA barcode. PLoS ONE, 6(5), e19254. [CrossRef]

- Lahaye, R., Van der Bank, M., Bogarin, D., Warner, J., Pupulin, F., Gigot, G., & Savolainen, V. (2008). DNA barcoding the floras of biodiversity hotspots. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(8), 2923-2928. [CrossRef]

- Kress, W. J. , & Erickson, D. L. (2007). A two-locus global DNA barcode for land plants: The coding rbcL gene complements the non-coding trnH-psbA spacer region. PLoS ONE, 2(6), e508. [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, A. J. , Kesanakurti, P. R., Burgess, K. S., Percy, D. M., Graham, S. W., Barrett, S. C. H., & Husband, B. C. (2008). Are plant species inherently harder to discriminate than animal species using DNA barcoding markers? Molecular Ecology Resources, 9(s1), 130-139. [CrossRef]

- Renner, S. S. (1999). Circumscription and phylogeny of the Laurales: Evidence from molecular and morphological data. American Journal of Botany, 86(9), 1301-1315. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J. , Lickey, E. B., Schilling, E. E., & Small, R. L. (2007). Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: The tortoise and the hare III. American Journal of Botany, 94(3), 275-288. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P. , Kumar, A., Nagireddy, A., Mani, D. N., Shukla, A. K., & Tiwari, R. (2015). Plant barcode loci as tools for species identification: A review. Biotechnology Advances, 33(5), 1892-1907. [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, P. M. , Forrest, L. L., Spouge, J. L., Hajibabaei, M., Ratnasingham, S., Van der Bank, M., Chase, M. W., & Cowan, R. S. (2009). A DNA barcode for land plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(31), 12794-12797. [CrossRef]

- Kress, W. J., Wurdack, K. J., Zimmer, E. A., Weigt, L. A., & Janzen, D. H. (2005). Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(23), 8369-8374. [CrossRef]

- CBOL Plant Working Group. (2009). A DNA barcode for land plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(31), 12794-12797. [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P. D. N. , Ratnasingham, S., & de Waard, J. R. (2003). Barcoding animal life: Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. Proceedings. Biological Sciences, 270(Supplement 1), S96-S99. [CrossRef]

- Newmaster, S. G., Fazekas, A. J., Steeves, R. A., & Janovec, J. (2008). Testing candidate plant barcode regions in the Myristicaceae. Molecular Ecology Resources, 8(3), 480-490. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Yao, H., Han, J., Liu, C., Song, J., Shi, L., Zhu, Y., Ma, X., Gao, T., Pang, X., Luo, K., Li, Y., Li, X., Jia, X., Lin, Y., Leon, C. (2010). Validation of the ITS2 region as a novel DNA barcode for identifying medicinal plant species. PLoS ONE, 5(1), e8613. [CrossRef]

- Raza, G.; Rahman, M.; Sajjad, Y.; He, S.; Yang, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, X. DNA barcoding: A molecular tool to identify economically important plant species. Plant Omics 2019, 12, 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kool, A., de Boer, H., Krüger, Å., Rydberg, A., Abbad, A., & Björk, L. (2012). Molecular identification of commercialized medicinal plants in southern Morocco. PLoS ONE, 7(6), e39459. [CrossRef]

| Kingdom | Plantae |

|---|---|

| Division | Magnoliophyts |

| Class | Mangoliopsida |

| Order | Solanales |

| Family | Solanaceae |

| Genus | Atropa |

| Species | A. belladonna |

| Belladonna sp. | Local name | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|

| Atropa belladonna | Atropa acuminate, Deadly Nightshade. | Belle-Dame, Bouton Noir, Grande Morelle, Herbe du Diable, Poison Black Cherries, Belle-Galante, Devil’s Herb, Morelle Furieuse, Baccifère, Divale, Herbe à la Mort, Cerise du Diable, Dwayberry, Naughty Man’s Cherries, Dwale, Guigne de la Côte, Devil’s Cherries. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).