1. Introduction

Breast milk is a nutrient with unique immunological and anti-inflammatory properties that protect against many diseases [

1]. The World Health Organization-WHO recommends starting breastfeeding immediately after birth and exclusively breastfeeding for the first 6 months. In addition, WHO stated in its latest report that breastfeeding can continue after the age of 2 [

2].

The World Health Organization announced that in 2020, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months worldwide was 44% [

2]. In Turkey, according to the Turkey Population Health Survey (TDHS) 2018 report, 41% of babies under six months were exclusively breastfed and this rate decreases with age [

3]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-CDC wants the breastfeeding rate to be 60.5% in the first six months [

4]. As can be seen, the rate in the world and in our country is far from the CDC’s target. Therefore, there is a need to start breastfeeding at an early stage and plan and implement various interventions to help maintain breastfeeding.

It is known that breastfeeding difficulties are often seen in the first weeks of the postpartum period and that various factors (age, education level, economic status, employment status, marital harmony, acceptance of the baby, etc.) are effective in the mother’s early cessation of breastfeeding [

5]. Mothers’ self-efficacy and perception of insufficient milk are also affected. are among the factors [

6]. It is estimated that in many countries mothers are unable to initiate or successfully continue breastfeeding because they do not believe they are producing enough milk [

7]. Breastfeeding self-efficacy perception is the competence the mother feels regarding breastfeeding. It is known that mothers with high breastfeeding self-efficacy have fewer problems initiating and maintaining breastfeeding. It has been determined that mothers with low breastfeeding self-efficacy cannot continue breastfeeding successfully and breastfeeding is stopped at an early stage [

8,

9]. In addition, low breastfeeding self-efficacy of the mother may cause milk to be perceived as inadequate 6. Studies on the subject show that mothers’ perception of milk and breastfeeding self-efficacy are interconnected [

6,

7].

Lack of milk production after birth or its late onset may be effective in the development of the perception of insufficient milk [

10]. In this case, milk production is supported by using non-pharmacological methods [

11]. Hot water application is often preferred to increase milk production [

12]. When the relevant literature was scanned, it was seen that there was no study using Thera Pearl, where heat application to the breast was generally done through a warm towel or hot water bottle.

Although there are studies on breastfeeding self-efficacy and milk perception, there is no study examining the effect of hot application applied to the breast with the help of Thera Pearl on mothers’ milk perception and postpartum breastfeeding self-efficacy.

This study aimed to examine the effect of hot application applied to the breast with the help of Thera Pearl in the postpartum period on milk perception and postpartum breastfeeding self-efficacy.

Research Hypotheses;

H1: Thera Pearl application positively affects mothers’ perception of milk.

H2: Thera Pearl application positively affects mothers’ breastfeeding self-efficacy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

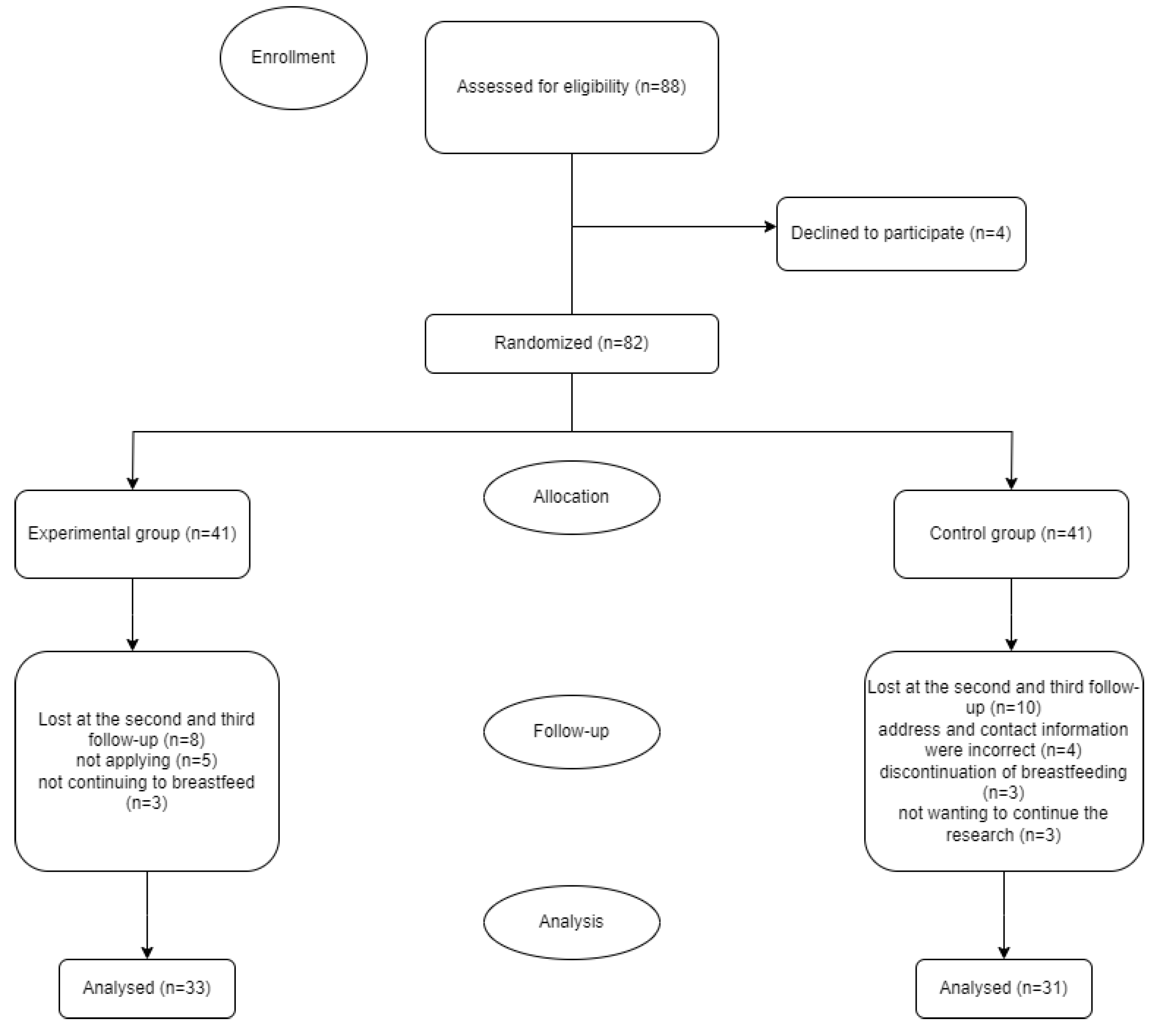

This study was conducted as a randomized controlled trial. This research was conducted in the gynecology service of a university hospital in Turkey between October 2022 and May 2023. The population of the research consisted of women who gave birth for the first time in the gynecology service of this hospital between these dates. The research was conducted with 2 different groups (experimental and control). The sample was calculated by power analysis at the 95% confidence interval and 0.05 significance level at the beginning of the study, and it was determined that there should be a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 35 pregnant women for each group. Considering that there might be data loss from the groups, the sample size was increased by 25% and 88 people were included in the study. However, 8 people in the experimental group were excluded from the study for various reasons (5 puerperal women did not use Thera Pearl effectively and 3 puerperal women did not continue breastfeeding). In the control group, 10 puerperal mothers were excluded because their address and contact information were biased (4), breastfeeding did not continue (3), and they did not want to continue the study (3). Therefore, the study was completed with a total of 64 puerperal mothers, 31 of whom were control and 33 were experimental. When the power of the study was calculated after the end of the study, the G-power of the study was found to be 0.95.

The study included postpartum mothers who were primary school graduates, between the ages of 18-45, primiparous, and who agreed to participate in the research. Postpartum women who did not meet these criteria were excluded from the study.

2.2. Data Collection

Personal Information Form, Breastfeeding Observation Form, Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale and Insufficient Milk Perception Scale were used to collect data.

Personal Information Form: This form consists of 13 questions created by the researcher by scanning the literature and includes the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

Breastfeeding Observation Form: This form was created by the researchers by scanning the literature. The breastfeeding observation form contains various questions regarding breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale: It is a scale developed by Dennis and Faux to evaluate the breastfeeding self-efficacy levels of mothers, the first form of which has 33 items. Later, a 14-item short form of the scale was developed in 2003 [

13].

Insufficient Milk Perception Scale: The scale developed by McCarter-Spaulding in 2001 to determine the perception of insufficient breast milk is a form consisting of 6 questions14. A minimum of 0 and a maximum of 50 points can be obtained from the scale. A high total score indicates that the perception of milk adequacy increases [

14].

2.3. Study Procedure

Postpartum women included in the study were randomized using single-blind randomization. Red (experimental) and white (control) colored balls were placed in a closed box. There were a total of 88 balls in the box, 44 red and 44 white. All postpartum women were asked to randomly choose a ball from the box one by one, and the selected ball was placed back in the box. If the selected ball was red type, it was assigned to the postpartum experiment group, and if the white type was assigned to the control group. This cycle continued until the desired number was reached for the experimental and control groups.

2.3.1. Experimental Group

The first interview with women who gave birth was held in the postpartum service of the relevant hospital. During this meeting, the Personal Information Form, Breastfeeding Observation Form, Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale and Insufficient Milk Perception Scale were filled out. At the same time, during this meeting, the telephone and address information of the participants were obtained and postpartum days 2-7. and 10-15. He was informed that a home visit would be made on the following days. The Thera Pearl application was explained to the woman in detail and the first application was performed together in the hospital.

Then the participant is 2-7 postpartum. days and 10-15. He was visited at his home once a day. Their status of applying Thera Pearl was questioned. The Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale and the Insufficient Milk Perception Scale were completed again.

Intervention material:

Information about the application:

Thera°Pearl (as

Figure 1) thermogel packs for hot therapy can be heated in the microwave for a maximum of 15 seconds inside their fabric covers, or in hot water by removing their fabric covers. The packages, whose cover has been removed, should be kept in boiled water for 1-2 minutes and then applied by placing them in the case.

This application should be done 4 times a day, in the morning, at noon, in the evening and at night before going to bed. Each application should be applied to both breasts and last at least 20 minutes.

2.3.2. Control Group

No intervention was applied to the control group. The first interview with women who gave birth was held in the postpartum service of the relevant hospital. During this meeting, the Personal Information Form, Breastfeeding Observation Form, Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale and Insufficient Milk Perception Scale were filled out. At the same time, telephone and address information of the participants were obtained during this meeting, and postpartum days 2-7. and 10-15. He was informed that a home visit would be made on the following days.

Then the participant is 2-7 postpartum. and 10-15. She was visited at home once a day, and the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale and the Insufficient Milk Perception Scale were filled out again.

The flow chart of the research is shown in

Figure 2.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by a university’s Clinical Research Ethics Board (IRB- B.30.2.ATA.0.01.00/410). The women were informed about the study, and their verbal and written consent was obtained. All women were explained that all collected data would be kept confidential.

The research is a study protocol registration system originating from the United States and has been registered on the “ClinicalTrials.gov” website, which is an important database especially for the registration of pharmaceutical and interventional studies, with ID: NCT05806892.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the comparison of demographic characteristics by groups. In this study, no statistically significant difference was obtained between the experimental and control groups and the distributions of socio-demographic characteristics (p>0.050). While 41.9% of the control group was between the ages of 26-30, 42.4% of the experimental group was between the ages of 20-25. In addition, it was determined that the majority of the participants in both groups lived in the province, were primary and secondary school graduates, did not work, had a nuclear family structure and their income was equal to their expenses.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the answers given by postpartum mothers to breastfeeding observation definition questions. In the study, no statistically significant difference was obtained between the experimental and control groups and the distributions of the parameters (p>0.050). When breast fullness was evaluated at the beginning of the breastfeeding process, no statistically significant difference was seen between the experimental and control groups (p = 0.796). Another important finding in

Table 2 is that while breastfeeding was successful in the first half hour in both the experimental and control groups, more than half of the babies in both groups were given formula.

For the control group, no statistically significant difference was obtained in the BSES median score during follow-ups at different times (p = 459). However, a statistically significant difference was obtained between the BSES median scores of the experimental group (p<0.001). In the experimental group, the 1st follow-up BSES median score was 42, the 2nd follow-up median value was 46, and the 3rd follow-up median score was 62. According to the groups, while there was no statistically significant difference between the BSES median score of the 1st and 2nd follow-up (p>0.050), a statistically significant difference was obtained between the PES median score of the 3rd follow-up (p=0.013). While the median BSES score at the 3rd follow-up was 47 in the control group, this value was 62 in the experimental group (

Table 3).

When

Table 4 is examined, it is seen that there is no statistically significant difference between the IMPS median score of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd follow-up according to the experimental and control groups (p>0.050). However, there was a statistically significant difference between the IMPS median score of the experimental group according to time (p<0.001). It was determined that the IMPS median score increased from the first follow-up to the third follow-up in the experimental group. There was no statistically significant difference between the IMPS median score of the control group according to time (p = 0.516).

4. Discussion

Initiating breastfeeding within the first 24 hours after birth is the gold standard in infant nutrition [

15]. Therefore, breastfeeding should be initiated and supported in the first 24 hours postpartum. In particular, identifying and correcting mothers’ faulty behaviors regarding breastfeeding has an important place in the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding [

16]. In this study, we saw that the majority of the experimental and control groups started breastfeeding within the first half hour and used formula despite milk secretion. Participants stated that their milk was not enough, so they used formula. However, when we examined the fullness of the breasts, milk secretion and the baby’s latching status in both groups in the first 24 hours, we found that it was unnecessary to start formula (

Table 2). This made us think that the mothers who participated in our study had a perception of insufficient milk, so they started formula feeding earlier. In another study similar to our study, it was found that although only 5% of women actually had insufficient milk physiologically, 50% of them had the perception of insufficient milk [

17]. These results are thought to be an important determinant of breastfeeding self-efficacy. If the mother’s breastfeeding self-efficacy level is low, this will cause the mother to perceive her milk supply as insufficient, to supplement the insufficient breast milk with formula, to decrease in the actual amount of milk, and eventually to stop breastfeeding [

14].

Hot application to the breast during breastfeeding is preferred only to increase lactation and eliminate breast problems (engorgement, clogged milk ducts, mastitis, breast abscess, infection, nipple sensitivity/pain, cracked nipple, etc.) [

18,

19]. However, in addition to physiologically increasing lactation and eliminating breast problems, these practices also have some psychological effects. It is thought that it will accelerate the readiness of women in particular. The amount of milk produced by a mother who is psychologically ready for the breastfeeding process and whose self-efficacy increases will also increase [

20]. Unfortunately, no study has been found in the literature showing the long-term psychological effects of hot application. In this study, we found that breastfeeding self-efficacy increased from the first to the third follow-up in the experimental group in which Thera pearl application was applied. However, this was not the case for the control group. In addition, at the last follow-up of the study, the breastfeeding self-efficacy of the experimental group was found to be significantly higher than the control group. Since hot application to the breast increases milk production, the self-efficacy of women in the experimental group may have increased. In addition, mothers’ comfort levels may have been increased with warm application, thus improving their self-efficacy perceptions. As a matter of fact, it has been accepted that there is a connection between mothers’ comfort levels and their perception of self-efficacy. It has been reported that mothers with high comfort levels have higher breastfeeding success [

21]. Hot application to the breast especially falls within the socio-cultural comfort dimension. Socio-cultural comfort is based on providing care and counseling in accordance with the person’s traditions and providing home care [

22,

23]. In our country, applying heat to the breast during breastfeeding has become a tradition. In addition, monitoring mothers and providing home care during the first 15 days, which is one of the most important postpartum periods, may have affected the results of the study.

In this randomized controlled study, we saw that the perception of insufficient milk did not change depending on the intervention between the groups, but the perception of milk improved from the first to the third follow-up in the experimental group where Thera pearl was applied. This result may be due to the fact that hot application increases breast milk. On the other hand, it is thought that the reason why there is no difference between the groups is due to women’s lack of knowledge about breast milk and breastfeeding. As a matter of fact, it is known that breastfeeding education has a positive effect on the perception of insufficient milk [

24].

5. Conclusions

As a result, self-efficacy and milk perception are important factors affecting breastfeeding. In this study, we found that Thera pearl application increased breastfeeding self-efficacy. Considering that mothers with high self-efficacy will be able to cope better with the difficulties they face and think positively and prefer breastfeeding, it can be said that our study reached its goal.

The perception of insufficient milk is a major obstacle for mothers to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months. It is said that the perception of insufficient milk plays an important role in stopping breastfeeding in many societies around the world. In the study, we found that milk perception did not change in the experimental group due to Thera pearl application. It is predicted that this result is due to the lack of information about breastfeeding. In this regard, we recommend conducting studies in larger sample groups in which Thera pearl application and breastfeeding education are given together.

Author Contributions

B.U.O, O.A. and H.Ö. were involved in the planning and design of the study. B.U.O, O.A. and H.Ö. were involved in the literature search, and H.Ö. analyzed the data. B.U.O, O.A. and H.Ö. developed the manuscript, and all authors agreed to its final submission. All authors guarantee the integrity of the content and the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by XXXX University Scientific Research Project Unit (ID 10274).

Informed Consent Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Atatürk University Faculty of Health Sciences Ethics Committee (2020/03/15-29.03.2020). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lawrence, R.A.; Lawrence, R.M. Breastfeeding: A guide for the medical professional; Elsevier Health Sciences, 2021; pp. 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World breastfeeding week 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/nutrition/campaigns/world-breastfeeding-week-2022.html.

- Turkish Population and Health Research Institute, 2019. 2018. Available online: http://www.hips.hacettepe.edu.tr/tnsa2018/rapor/TNSA2018_ana_Rapor.pdf.

- CDC. Breastfeeding report card. 2016. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2016breastfeedingreportcard.pdf.

- Huang, Y.Y.; Lee, J.T; Huang, C.M; Gau, M.L. Factors related to maternal perception of milk supply while in the hospital. J Nurs Res. 2009, 17, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, K.; Dennis, C.L.; Tatsuoka, H.; Jimba, M. The relationship between breastfeeding self-efficacy and perceived insufficient milk among japanese mothers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008, 37, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, L. Maternal perceptions of insufficient milk supply in breastfeeding. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2008, 40, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.H. Breastfeeding self-efficacy: The effects of a breastfeeding promotion nursing intervention. University of Rhode Island, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- O’campo, P.; Faden, R.R.; Gielen, A.C.; Wang, M.C. Prenatal factors associated with breastfeeding duration: Recommendations for prenatal interventions. Birth. 1992, 19, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugraheny, E.; Alfiah, E. Faktor penghambat dan penerapan asi eksklusif. J Akbiduk. 2015.

- Fazilla, T.; Tjipta, G.; Azlin, E.; Sianturi, P. Pengaruh domperidon terhadap produksi asi pada ibu yang melahirkan bayi premature. Maj Kedokt Nusant J Med Sch. 2013, 46, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraheni, D.; Heryati, K. Metode speos (stimulasi pijat endorphin, oksitosin dan sugestif) dapat meningkatkan produksi asi dan peningkatan berat badan bayi. J Kesehat. 2017, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluş Tokat, M.; Okumuş, H.; Dennis, C.L. Translation and psychometric assessment of the Breast-feeding Self-Efficacy Scale—Short Form among pregnant and postnatal women in Turkey. Midwifery. 2010, 26, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarter-Spaulding, D.E.; Kearney, M.H. Parenting self-efficacy and perception of insufficient breast milk. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing 2001, 30, 515–522. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinska, M.; Sobczak, A.; Hamulka, J. Breastfeeding knowledge and exclusive breastfeeding of infants in first six months of life. Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny 2017, 68, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Özsoy, S.; Dündar, T. Breastfeeding behaviors of mothers in the early postpartum period (breastfeeding in the early postpartum period). Children’s Journal 2022, 22, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hector, D.; King, L. Interventions to encourage and support breastfeeding. New South Wales Public Health Bulletin. 2005, 16, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Section on, Breastfeeding; Eidelman, A.I.; Schanler, R.J. Section on Breastfeeding; Eidelman, A.I.; Schanler, R.J. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012, 129, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, V.; Bharti, B.; Kumar, P.; Mukhopadhyay, K.; Dhaliwal, L. First hour initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks: Prevalence and predictors in a tertiary care setting. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2014, 81, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya Odabaş, R.; Sökmen, Y.; Taşpinar, A. Examination of postgraduate theses about non-pharmacological methods applied during breastfeeding in Turkey. Dokuz Eylül University Faculty of Nursing Electronic Journal 2022, 15, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Başer, M.; Mucuk, S.; Korkmaz, Z.; Seviğ, Ü. Determining the needs of mothers and fathers regarding newborn care in the postpartum period. Journal of Health Sciences. 2005, 14, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gölbaşı, Z. Breastfeeding behaviors of women in the first 6 months postpartum and the effect of breastfeeding attitudes in the prenatal period on breastfeeding behaviors. Hacettepe University Faculty of Nursing Journal. 2008, 15, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kolcaba, K. Comfort theory and practice: A vision for holistic health care and research. Springer Publishing Company. 2003.

- Işık, C.; Küğcümen, G. Examination of lactating mothers’ perception of insufficient milk in terms of different variables. Samsun Health Sciences Journal. 2021, 6, 491–506. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).