1. Introduction

The global economy is in the process of transforming itself into a digital economy. Digitalization started as an idea with good potential and has now turned into a powerful force that is in the process of disrupting virtually all industries worldwide. Many markets today are characterized by an increased rate of new products and an increased service launch rate combined with decreased product life spans. Emerging business ecosystem structures offer new venues for value creation and capture as well as increased efficiency in both production and delivery which allows businesses to target completely new customer segments (Kraus et al. 2020; Payne et al. 2020). Artificial intelligence (AI) is a constellation of many different technologies designed to work together to enable machines to perform tasks with human-like levels of intelligence. AI technologies are reshaping the key elements of strategy such as customers, competition, data, innovation, and value creation (Rogers 2016). The synergy of these elements aptly represents the new landscape many businesses face today. AI technologies have become a key business factor (some would even say actor) that is enabling the kind of autonomous work processes and self-organizing systems that can increase a firm’s market reach (Schallmo, Williams, and Boardman 2017) and reduce barriers to its international expansion (Nambisan et al. 2019; Schallmo and Tidd 2021).

AI technologies should therefore be seen as an intrinsic component in the development of any firm’s digital strategy and one of the pillars of its business model (Niemand et al. 2021; Soluk et al. 2021). The use of AI transforms key parts of a firm’s business model and impacts their interplay both internally and externally (Copeland 2019; Kraus et al. 2021). A firm’s deft adoption of AI technologies increases the quality of its cross-border interactions with key business stakeholders no matter their geographic location or institutional distance (Nambisan, Zahra and Luo 2019; Verhoef et al. 2021). As such, the adoption of AI (both in terms of resources and capabilities) is a key element in the digitalization of business models and, theoretically speaking, should therefore be approached from an ecosystem business perspective (Nambisan, Zahra and Luo 2019; Kraus et al. 2021).

In this article, we examine how AI can enhance the value propositions (VPs) of new companies based on results from a study we led in 2021. Taking an AI perspective on digital transformation aligns with recent research studies that suggest that AI technologies, including machine learning (ML) and data analytics (DA), are better positioned than other enabling technologies (such as blockchain and cloud computing) to impact how businesses operate and create and capture value (Majhi, Mukherjee and Anand 2021; Sjödin, Parida, Palmié and Wincent 2021).

A VP is the best expression of a company’s business strategy and innovative capacity, that is, its ability to coordinate a combination of resources from multiple stakeholders to develop new products and services and shape valuable market offers to address the needs of specific customer target groups (Baldassarre et al. 2017; Payne et al. 2017). Our study considered a VP as an integrative construct and positions VP development as a bridge between corporate strategy and business model development. The focus of this approach is in keeping with recent VP research which shows how a VP is “a strategic tool that is used by a company to communicate how it aims to provide value to customers” (Payne et al. 2017, p. 467). The unique strategic role of VPs to engage customers and other relevant business stakeholders has been widely acknowledged in the literature (e.g., Amit and Zott 2021; Onetti et al. 2012; Winter 2003).

Our study stems from a belief that new company research is a fruitful arena where digitalization and VP research streams could merge to help develop valuable insights for both scholars and practitioners (Bailetti, Tanev and Keen, 2020). Indeed, Berglund et al. (2018) highlighted the need for a distinct body of pragmatically oriented knowledge that could bridge the gap between entrepreneurship theory and entrepreneurial practice. Seeing as the need of new companies to acquire AI and VP development resources and capabilities is distinct (i.e., different from established companies with small or moderate growth objectives) and seeing as many of these very resources belong to external partners (thereby compelling a multi-stakeholder perspective on AI and VP development), this new research arena presents a unique potential to help advance research about not only VPs, but also business ecosystems, scaling, AI value, and digitalization.

This article therefore aims to explore how AI can enhance VP development-associated activities led by new companies. To do so, we sought to develop a VP development framework that could offer an explicit business activity structure that could then enable an analysis of the potentially beneficial impacts of AI resources and capabilities on specific VP development activities. To develop such a framework, we examined extant literature to generate a corpus of actionable insights about VP development. We then performed topic modelling (Blei 2012; Alghamdi and Alfalqi 2015; Hannigan et al. 2019; Lu and Chesbrough 2022; Thakral, Sharma and Ghosh 2024) to identify an emerging set of activities that could constitute the core elements of a VP development framework. We then examined each activity in terms of its potential to be enhanced by AI resources and capabilities and identified the ones that could. Our analysis then sought conclusions that could be used as future research propositions for scholars or as actionable insights for practitioners as advised by Makadok et al. (2018).

The study we led contributes to literature in two different ways. The first is methodological since this is the first time that topic modelling has been applied to a corpus of management research assertions to develop an activity-based VP development framework. Topic modelling is the process of identifying latent topics in a large set of text documents. It is an example of the Natural Language Processing (NLP) method which examines collections of unstructured text data to identify topics otherwise impossible to find through human efforts alone. The various applications of topic modelling in management research have recently been summarized by Hannigan et al. (2019). Its application in the study discussed here is an example of how an NLP technique could benefit VP research in the entrepreneurial context of new companies. The study’s second contribution lies in developing insights on how the adoption of AI resources and capabilities, or AI-driven digitalization, can enhance the business activities identified as core elements of the proposed VP development framework. As such, our results ultimately seek to make explicit any links between new companies’ AI resources and capabilities and the development of their VPs.

This article first summarizes the results of a comprehensive review of literature streams focused on the relationship between digital transformation, AI business value, VP development, and business ecosystems. After outlining the methodology used for our study, we summarize the results of our topic modelling text analytics approach on the list of actionable insights from our literature review. We then group these insights into subsets of activities that we might then consider elements of a VP development framework. Once associated with the VP development framework elements, we then reexamine the actionable insights to identify specific activities that could be enabled and empowered by AI-driven digitalization. We then use our findings to shape conclusions that could feed research proposition development for future studies or offer insights for practitioners working with new companies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. AI Perspective on Digital Transformation

AI-driven digitalization is among the most important initiatives firms can engage in or simply undergo in light of competitive pressure emerging from their rivals’ digitalization practices (Garbuio and Lin 2019; Wolf 2020; Wagner 2020). AI is changing how businesses acquire, use, and organize their resources and interact with one another, potentially creating a competitive gap between businesses successfully making the transition and those that are still contemplating it (Ransbotham, Kiron, Gerbert and Reeves 2017).

The pervasive presence of AI technologies (Dwivedi et al. 2021; Obschonka and Audretsch 2020) and emerging digital technologies, such as blockchain, internet-of-things, and robotics, are expected to have far-reaching effects on business (Akter, Michael, Uddin, McCarthy and Rahman 2020). Even though the impact of these technologies will not be universally equal, the wide introduction of new digital technologies clearly signals the need for firms to undergo digital transformation. AI manifests a great potential to contribute to digital transformation because AI capabilities are fundamentally rooted in data. Whereas the data that emerges from a digital transformation has limited value on its own, AI technologies can help transform this data into valuable business insights.

Although AI has improved the market reach of firms (Reim, Åström and Eriksson 2020) and offered ventures new possibilities successfully competing against established firms in international markets immediately upon their inception (Buccieri Javalgi and Cavusgil 2020), new growth-oriented companies undergoing a digital transformation empowered by AI do not operate in a vacuum. Fundamentally, an AI journey is ultimately about building a predictably growing and sustainable customer base and has to be strengthened and supported by properly designed digitized business models, operational processes, value chains, and by forward-looking leadership and organizational culture. New companies inevitably need to acquire AI resources and capabilities and adopt VP development processes that are different from those that established companies with small or moderate growth objectives would require.

2.2. The Business Value of AI Resources and Capabilities

Recent research on the business value of AI suggests that AI resources and capabilities could offer firms a significant value-driving impact and help them achieve an operational and competitive advantage, even if there is a significant lack of understanding about how to appropriate value from AI (Mishra and Pani 2020). An increasing number of studies focus on examining the specific dimensions of value that could be enabled through AI resources and capabilities. For example, Wagner (2020, p. 3) defines a firm as artificially intelligent if it “deploys classic economic factors of production human labor, capital and land in combination with machine labor in the form of AI agents.” He adopts the economic theory of the firm to systematically explore five ways AI might impact it, that is: AI intensifies the effects of economic rationality on the firm; AI introduces a new type of information asymmetry; AI can perforate the boundaries of the firm; AI can create triangular agency relationships; and, AI has the potential to remove the traditional limitations of integration.

Davenport and Ronanki (2018) emphasize how businesses should examine the potential value of AI through the lens of business rather than technological capabilities. They point out that AI can support the automation of business processes, gaining competitive insight through data analysis, and engaging with customers and employees. Majhi et al. (2021) consider AI and ML as subfields of cognitive computing and cognitive technologies. By drawing on both academic and practitioner literature, they developed a conceptual model that shows how cognitive analytics (CA) technologies can add value to organizations by enabling and enhancing three dynamic organizational capabilities: sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring. The importance of sensing is rooted in the constantly changing nature of consumer needs, technological advancements, and competitor activities in modern, fast-paced business environments. CA technologies enhance a firm’s sensing capabilities by helping them to collect and analyze real-time data, anticipate and explore new trends, and gather information from multiple sources to capture emerging user behaviour across different markets and contexts. In addition, CA helps firms seize opportunities by facilitating agile development and allowing production and resource utilization process adjustments. It facilitates the shaping of new strategies and innovative offerings by substantially increasing the speed and efficiency of decision-making. Last, but not least, CA enhances the capacity of firms to reconfigure. Teece (2006) explains how reconfiguring involves “enhancing, combining, protecting and, when necessary, reconfiguring the business enterprise’s intangible and tangible assets” to avoid inertia and path dependencies (p. 1319). CA technologies empower a firm’s dynamic reconfiguring capabilities and enable them to reshape markets (Nenonen, Storbacka and Windahl 2019) and expand the frontiers of analytics-based decision-making by shaping new valuable partnerships, mergers, and acquisitions (Berman and Dalzell-Payne 2018).

Huang and Rust (2021) developed a strategic AI-usage framework to help firms engage with customers and offer them different service-based benefits. This framework sees AI expanding across three fronts: mechanical, thinking, and feeling. Mechanical AI could help in terms of cost leadership and standardization, primarily at the service delivery stage and when service is routine and transactional. Thinking AI could help in terms of quality leadership and personalization, primarily at the service creation stage and when service is data-rich and utilitarian. Feeling AI could help in terms of relationship leadership, primarily at the service interaction stage and when service is relational and high contact (Huang and Rust 2021, p. 36).

Paschen, Wilson and Ferreira (2020) offer a comprehensive discussion of the role of AI in enhancing sales processes. They identified the value of AI systems at each stage of the sales funnel, as well as clarified the role of human intelligence and decision-making at each stage of this AI-enabled sales funnel. They posit that there is a complementarity between humans and AI and that AI’s enormous information processing capacity can augment human intelligence or even replace well-defined and repeatable human tasks in a B2B sales context. For example, it could help build rich customer prospect profiles, update lead generation and lead qualification models via machine learning, personalize and customize communication messages and channels, establish contacts via digital agents (e.g., chatbots), enable fast prototyping, curate competitive intelligence, enable dynamic pricing, automate workflows and post-order services, and uncover new customer needs, just to name a few.

Güngör (2020) explains that organizations can explore two major AI value-creation opportunity pathways: one lying in the value chain, and one emerging from the adoption of a multi-stakeholder benefit analysis perspective. For example, AI could be fully integrated into business value chains and, more specifically, use replenishment models to manage inbound logistics, robots in operations and order fulfillment, dispatch algorithms for delivery cost optimization, and recommendation engines to optimize service levels. Güngör also argues that AI could also provide “support functions in human resources to predict the best candidates to hire, in finance to prevent frauds, in procurement to optimize number of suppliers, etc.” The second opportunity pathway relates to multi-stakeholder benefit analysis of revenue growth, cost savings, risk mitigation or customer experience, and more. Such analyses should help evaluate how value is shared or distributed and if there exists any potential conflict of interest between stakeholders (be they customers, employees, suppliers, co-innovation partners, or society at large).

AI researchers and practitioners have worked together to instrumentalize the integration of AI resources and capabilities into business development processes. One example of these joint efforts is the development of canvas approaches in the implementation of AI business value (Zawadzki 2020; Kerzel 2021). The adoption of AI canvas approaches would indicate that the AI field is moving toward a higher stage of maturity which should inspire even more researchers to invest themselves in this domain.

2.3. Value Propositions in the Context of New Growth-Oriented Companies

The importance of the VP construct and the multiple issues associated with the development of VPs have been discussed in the literature (Anderson et al. 2006; Frow and Payne 2011; Payne et al. 2020). Despite this, the VP construct has often been used casually and applied haphazardly rather than strategically and rigorously (Lanning 2000). A VP should be company’s single most important organizing principle (Webster 2002) and thus one of a company’s most valuable resources (Bailetti et al. 2020). VPs should therefore have a strong influence on key aspects of any business venture such as the acquisition of complementary resources needed for the value creation process, operations management, inter-organizational structures, and interactions with all relevant stakeholders. The development of VPs should therefore be done using a multi-stakeholder perspective to reciprocally align all VPs for all relevant actors in the business ecosystem (Ballantyne et al. 2011; Eggert et al. 2018; Bailetti et al. 2020). Instead of focusing on trying to predict trends in an uncertain environment, new venture management teams could focus on achieving achievable ends through known means (Sarasvathy 2001) by designing, developing, and implementing VPs that could help them achieve their strategic scale-up objectives.

According to Bailetti et al. (2020) and Nambisan et al. (2019), the extant literature appears to overlook the important link between a company’s VP portfolio and its business strategy. Onetti et al. (2012) make a clear distinction between a firm’s business model and its strategic concepts and claim that business model frameworks should exclude the VP construct which, according to them, should be part of the higher order of a firm’s strategic elements (Onetti et al. refer to Kothandaraman and Wilson 2001, and Winter 2003). Amit and Zott (2021) also point out that early definitions of the VP construct emphasize links to a firm’s strategy and performance by observing that a winning strategy is always rooted in a superior VP (Amit and Zott refer to Lanning and Michaels1988). Amit and Zott (2021), Bailetti et al. (2020) and Nambisan et al. (2019) agree that VPs should be examined from a strategic point of view since every focal firm needs to offer some form of VP not only to customers but also to all other stakeholders involved in its business model.

Several studies have highlighted the importance given by marketing scholars to customer VPs (Payne et al. 2020; Wouters et al. 2018). Payne et al. (2017) define a customer VP as “a strategic tool facilitating communication of an organization’s ability to share resources and offer a superior value package to targeted customers” (p. 472). The marketing literature has emphasized the need for firms to articulate benefits and costs relevant to targeted customers as well as functional and experiential features of the differentiation aspects of their offerings and of customer experience in particular (Holttinen 2014; Payne et al. 2017). The customer is indeed a key stakeholder, but not the only stakeholder, and, for many ventures, not always the most important one. Entrepreneurship and innovation literature shows that ventures tend to focus on the development of new products and services when targeted markets are not clearly defined (Bocken and Snihur 2020; Schepis 2020). Recent literature has also emphasized the importance of proper resource configuration and practices in enabling the delivery of key benefits, the sharing of resources, and the integration of the value chain’s key actors in a value co-creation process (Grönroos 2011). Skålén et al. (2015) define VPs as “promises of value creation that build upon configuration of resources and practices” (p. 144). They emphasize the importance of value co-creation with customers as well as the integration of resources provided by other relevant stakeholders.

Most of the research on the interaction between firms and their stakeholders addresses the needs of large established firms and is dominated by a narrow focus on the firm–customer–supplier triad. Yet it has been shown that the realities of established firms are significantly different than those of new ventures (Ballantyne et al. 2011; Corvellec and Hultman 2014). Considering how different actors working together by sharing resources to initiate an offer is key to the development and alignment of a company’s VP portfolio that corresponds to its most relevant business objectives (Ballantyne et al. 2011; Truong et al. 2012; Bailetti et al. 2020), Eggert et al. (2018) argue that a VP not only communicates value but also implies a reciprocal engagement involving all relevant actors, though they do not elaborate on how this reciprocal engagement takes place or precisely how it is relevant for a given venture. Wouters et al. (2018) shed some light on this by suggesting that new ventures interested in growth should shape and align at least two VPs with their business customers: a typical VP based on an innovative offer and a leveraging-assistance VP conveying what the business customer gains from providing support and resources at the early stage of the new venture’s business life cycle. The focus here remains on the venture–customer dyad at a stage where most ventures are struggling to identify their real customers. This limited focus signals an opportunity to extend research by studying the development of explicit VPs for all relevant stakeholders, from investors and employees to external resource owners and others.

Little is published about the factors that enable new companies to scale rapidly and the ways they can align their VP portfolio with their scaling objectives. Such an alignment implies the need to incorporate any scale-up objectives into a company’s business model through its configuration of the resources and activities that not only create value for customers but also allow it to capture part of that value and distribute it back to key resource owners (Zott et al. 2011). Scalability is defined as the extent to which a VP and its corresponding business model can help achieve the desired value creation and value capture targets by increasing the customer base without having to proportionately add additional resources (Zhang et al. 2015). As suggested by Shepherd et al. (2020), the organizing phase of a venture has a profound impact on its performing phase that in turn will (or will not) lead to any potential scale-up.

Recent studies have identified an explicit link between the growth orientation of new technology companies and the novelty and attractiveness of their VPs. Rydehell et al. (2018) point out that finding new and innovative ways to offer value to customers is important for any company to achieve high sales growth, as well as rapid geographic expansion to new markets. Malnight et al. (2019) suggest that companies pursue high growth by creating new markets, serving broader stakeholder needs, changing the rules of the game, redefining the playing field, and reshaping their VPs. Bailetti et al. (2020) point out that such companies should develop capabilities to access, combine, and deploy the resources required to create value and scale by offering their external resource owners returns they could not otherwise obtain on their own (Bussgang and Stern 2015; Girotra and Netessine 2014). According to Bailetti et al. (2020), the VPs of NCCSREs have two distinctive features: they enable themselves and any number of external stakeholders to directly transact without an intermediary and they increase investments that help create and improve business transactions over time.

Bailetti et al. (2020) also identified three factors that make the VP portfolio one of the most valuable company resources: it strengthens the company’s scale-up capabilities, it increases the demand for its products and services, and it fosters investments in the conceptualization, development, maintenance, and refinement of its VPs (Bailetti et al. 2020). As such, a properly aligned VP portfolio becomes a valuable resource that enables the alignment of other resources, improves interactions with complementary ecosystem actors, and transforms these actors into preferred stakeholders who in turn can contribute to the scale-up process.

2.4. Ecosystem Perspective on VP Development

Any new venture requires people with entrepreneurial imaginativeness (Shepherd et al. 2020). The act of conceptualizing a new venture is “a cognitive skill that combines the ability of imagination with the knowledge needed to stimulate various task-related scenarios in entrepreneurship” (Kier and McMullen 2018, p. 2266). This cognitive skill is essential to take an idea and move toward identifying an opportunity and then creating a venture to exploit it (Shepherd et al. 2020; Vogel 2017). It implies the shaping of a novel offering (Eisenmann 2013) through the exploitation of resources beyond the ones controlled by the nascent company (Casali et al. 2018; Kollmann et al. 2017). Such exploitation is the result of a multi-actor process in which different business ecosystem stakeholders are actively engaged (Adner 2017; Stam and van de Ven 2019).

In a globalized world with increasingly complex and interrelated technologies, entrepreneurial innovation ecosystems are vital for ventures looking to implement complex VPs (e.g., Adner 2017; Dattée et al. 2018). Every venture committed to scale operates in an environment where different ecosystem actors are actively engaged in complementing the value creation process. Any such venture needs to join a business ecosystem that provides it “the alignment structure of the multilateral set of partners that need to interact in order for a focal value proposition to materialize” (Adner 2017, p. 42). The preferred ecosystem partners will be the ones more committed and more efficient than others in enhancing the logic and the alignment of company’s VP portfolio (Adner 2017). Securing the commitment (or pre-commitment) of valuable stakeholders can be crucial to a venture’s scaling performance (Akemu et al. 2016; Shepherd et al. 2020). Even though the actors of an ecosystem have a certain autonomy in terms of how they design, price, and operate their respective business modules, there is still a need for coordination. An ecosystem defines and provides processes and rules that help resolve any emerging coordination issues and also encourages alignment between ecosystem actors through rules of engagement, standards, and codified interfaces (Jacobides et al. 2018). The modularity of resources and contributions is a necessary but in and of itself an insufficient condition for the existence of an ecosystem (Baldwin 2008; Langlois 2003). For an ecosystem to emerge and be useful, there must be a significant need for coordination that cannot be met by the hierarchy imposed by a focal firm (Dattée et al. 2018). What makes ecosystems unique is that actors “can choose among the components (or elements of offering) that are supplied by each participant, and can also, in some cases, choose how they are combined” (Jacobides et al. 2018 p. 2260).

Jacobides et al. (2018) identified two types of complementarities that can unambiguously characterize the coordination of activities and resource sharing between ecosystem actors. The first is unique complementarity, either where an activity or component offered by one actor requires the activity or component of another, but not vice versa, or where two activities, A and B, of two different actors both require each other. The second, supermodular complementarity, could be described as “more of A makes B more valuable, where A and B are two different products, assets, or activities” (p. 2262). The distinctive feature of ecosystems is that they provide an alignment structure where different actors can engage with each other in value creation through these unique and supermodular complementarities, in production and/or consumption, which can both be coordinated without the need for vertical integration. Defining business ecosystems in this way offers an opportunity to advance VP research and practice.

3. Research Methodology

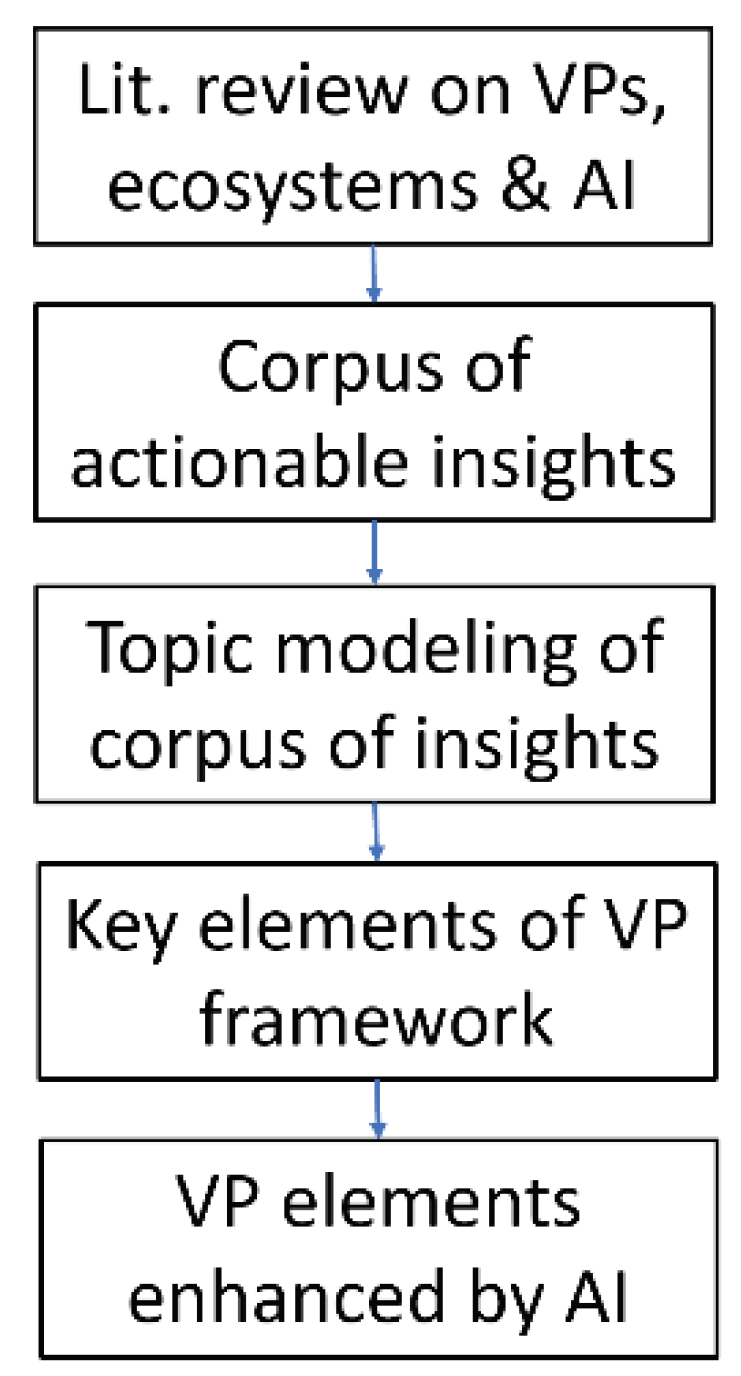

The objectives of the research study presented in this article were to (i) perform a systematic management research literature review; (ii) generate a corpus of assertions on how new companies can shape and strengthen their VPs; (iii) apply topic modelling to examine this corpus; and (iv) identify the key elements of a VP development framework emerging from the topic modelling analysis; and (v) elucidate explicit links between a new company’s AI resources and capabilities and the core elements of its VP framework.

Figure 1.

Symbolic representation of the study’s objectives.

Figure 1.

Symbolic representation of the study’s objectives.

In two earlier articles, we developed a preliminary set of assertions associated with VP development in the context of new companies (Bailetti and Tanev 2020; Bailetti et al. 2020). In the present article, we summarize the results of a systematic literature review that was used to expand our initial set of assertions. We searched the Web of Science database for journal research articles containing the string “value proposition” in titles, abstracts, and author-provided keywords. Our search resulted in 84 articles that were further examined by all co-authors to gauge their relevance to our study. A subset of 14 articles was identified as a core source of assertions based on more comprehensive review sections, descriptions of VP development frameworks, and actionable insights that could be turned into practical advice for real-world companies (Bailetti et al. 2020; Ballantyne et al. 2011; Eggert et al. 2018; Frow et al. 2014; Kristensen and Remmen 2019; Malnight et al. 2019; Mishra et al. 2019; Nenonen et al. 2019; Payne et al. 2020; Payne et al. 2017; Rydehell et al. 2018; Skålén et al. 2015; Truong et al. 2012; Wouters et al. 2018). These articles were then examined independently by all co-authors and used as a source for the formulation of distinguishable actionable insights. The VP insights were complemented by insights extracted from selected recent research articles focused on business ecosystems (Jacobides et al. 2018; Dattée et al. 2018) and AI-based business value (Mishra and Pani 2020; Paschen et al. 2020). The process of developing these actionable insights included multiple interactive sessions including entrepreneurs, business mentors, representatives of organizations supporting small and medium company innovation, and other researchers. This feedback helped the final formulation of the assertions and ensured the use of language that is familiar to executive managers of new firms and new companies in particular. The process resulted in a corpus of 182 assertions referring to the development and alignment of VP portfolios of such companies.

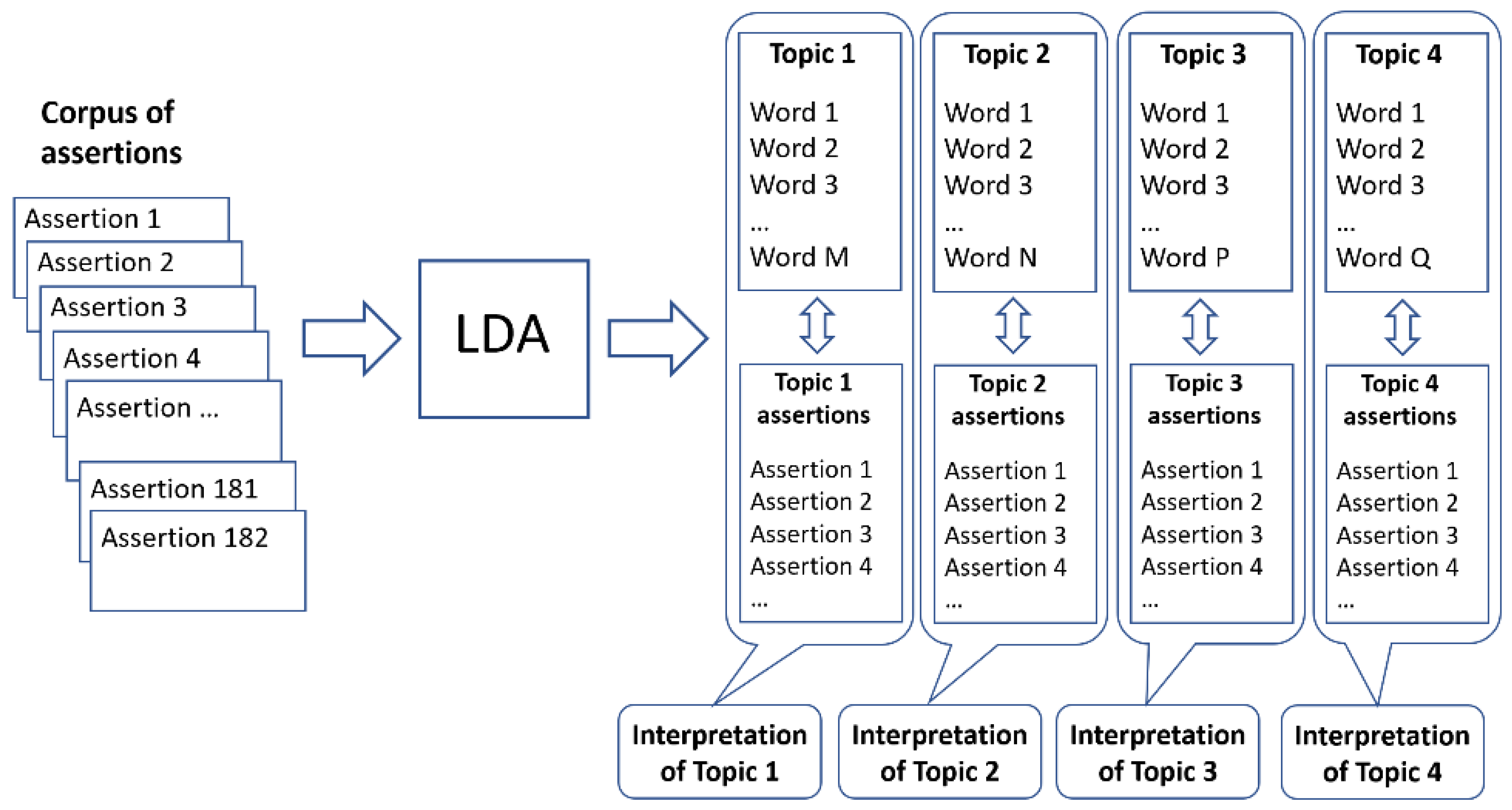

The next step of our study involved topic modelling analysis (Blei 2012; Alghamdi and Alfalqi 2015; Hannigan et al. 2019; Lu and Chesbrough 2022; Thakral, Sharma and Ghosh 2024) as a text mining approach to the identification of emerging latent themes referring to the groups of activities defined by the texts included in the corpus of 182 assertions. We used a text analytics tool1 based on the most popular topic modelling algorithm, known as Latent Dirichlet Allocation, or LDA (Blei 2012). The LDA method has gained popularity due to its ability to process large corpora of text documents resulting in the identification of emerging latent topics across all the documents (Blei, 2012). It posits that each document is a mixture of a small number of topics and that each word in a document could be associated with one or more of the document’s topics. In more technical terms, the LDA approach inputs a document-term matrix, for which the rows are the specific word counts and the columns are the specific texts corresponding to the documents in the corpus.

LDA identifies distinct topics across the corpus by observing words that tend to co-occur frequently within each of the texts. It outputs a document-topic matrix, for which each document is assigned to a probabilistic mixture of topics. The combinations of words per topic help identify specific themes that are latently present in the corpus. LDA also organizes the corpus by clustering the assertions corresponding to each topic (as shown in

Figure 2). The assertions clustered in a given topic are ranked in terms of the degree of their association with it. А closer examination of the topical organization of the assertions enables the interpretation of the overall theme and the labelling of the topics (Boyd-Graber et al. 2017). The number of topics to be used in the analysis is specified by the researchers.

Figure 2 provides a symbolic representation of the topic modelling process. A more detailed description of the original algorithm can be found in Blei (2012).

Our next step was to examine the consistency of the topics as a whole and the possibility of considering the groups of VP development activities associated with each of them as key elements of a VP development or evaluation framework for new companies. The last step, and the ultimate goal of our study, was to examine the extent to which the activities suggested by the assertions and associated with a given topic could be enabled or enhanced by means of AI resources and capabilities. Following this examination, we reflected on the ability of AI and AI-driven digitalization to enhance the VPs of new companies.

4. Topic Modelling Results

4.1. Topic Model of the Corpus of Actionable Value Proposition Insights

Our topic modelling analysis identified seven topics, each defined by a set of words and a set of topic-specific assertions. The words and the assertions associated with each of the seven topics are listed in the

Appendix A. A close examination of these sets of assertions allowed us to label each set as follows:

Value created,

Stakeholder value propositions,

Foreign market entry,

Customer base,

Continuous improvement,

Cross-border operations, and

Company image. The purpose of these labels was to emphasize the thematic distinctiveness of each topic and shed light on the overall content of their corresponding assertions. The labels should be therefore seen as thematic pointers emerging from the topics and not as comprehensive content signifiers. The specific assertions are the real content of each topic.

Topic 1 (Value created) refers to a given venture’s access to, and combination of, complementary internal and external resources relevant to value creation for all its relevant stakeholders. Topic 2 (Stakeholder value propositions) focuses on various aspects and the alignment of the VPs to key stakeholders such as investors, customers, suppliers, etc. Topic 3 (Foreign market entry) includes assertions related to successfully turning local offers into global ones. Topic 4 (Customer base) focuses on activities that result in engaging and attracting more customers, activities associated with the end goal of a scaling strategy, that is, increasing the customer base profitably. Topic 5 (Continuous improvement) includes assertions about improving the value creation process and refining the alignment of company’s VP portfolio. Interestingly, we find here specific assertions about improving the firm’s cybersecurity which speaks to online business interactions and global reach. Topic 6 (Cross-border operations) focuses on knowledge sharing and cross-border coordination activities and on the need for stronger positioning in cross-border networks. Topic 7 (Company image) refers to the brand identity of the company and how it differentiates itself from its competitors.

4.2. Shaping a Value Proposition Development Framework

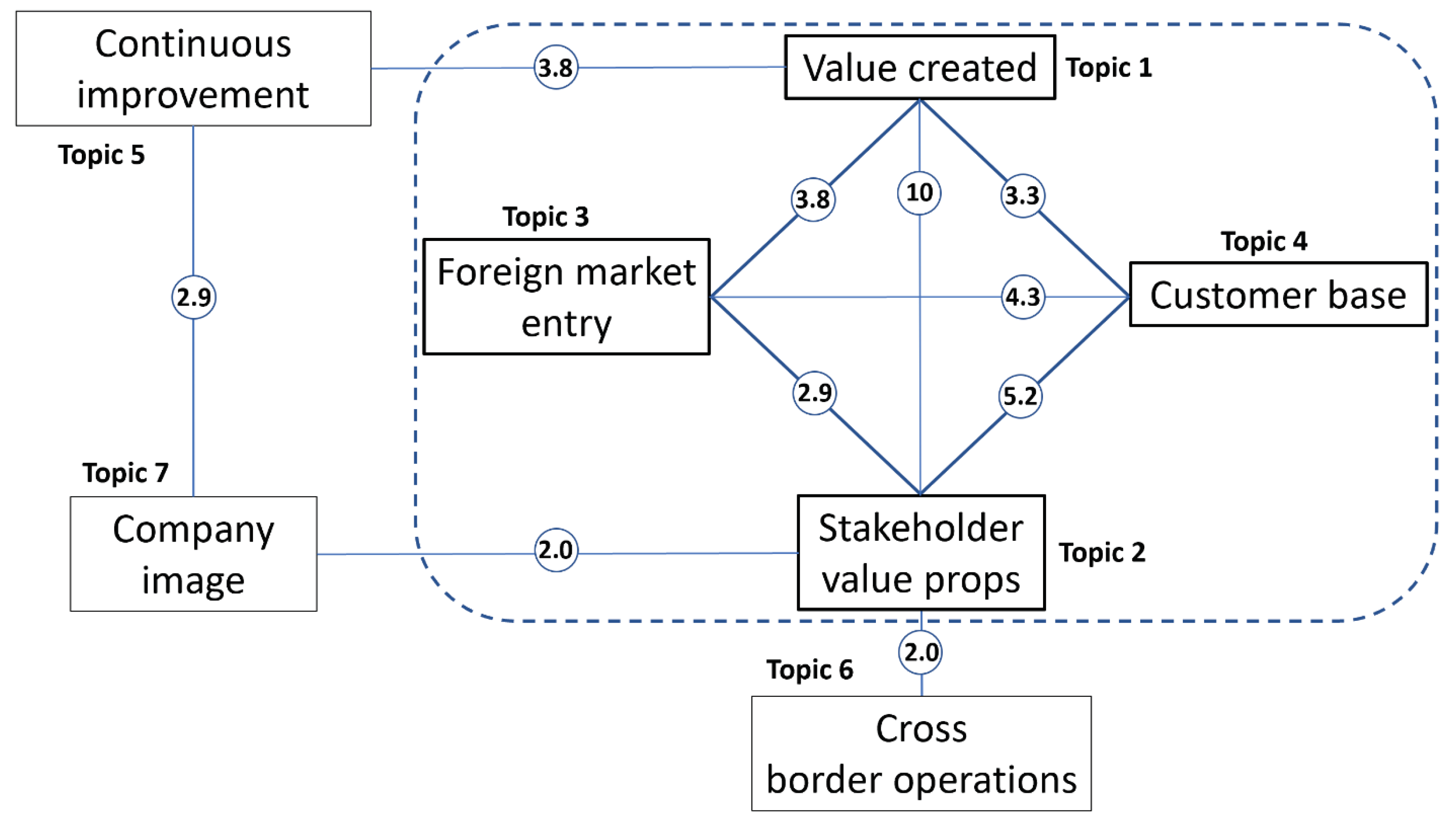

The seven topics outlined above already suggest a conceptual framework substantiated by the specificity of the assertions (each associated with actionable insights) associated with each topic. After further examination of the potential logical relationships between them, the associated insights were conglomerated into seven documents, one per topic, and the cosine similarity values between the seven documents were calculated. Cosine similarity is a measure used to evaluate the semantic proximity of documents or provide a ranking of documents with respect to a given set of search words, a phrase, or a paragraph (Anandarajan et al. 2019).

The resulting VP framework is shown in

Figure 3. The numbers along the links between topics indicate the normalized cosine similarity between the seven documents created by the process. The cosine similarity values were normalized by the maximum value found between Topic 1 (

value created) and Topic 2 (

stakeholder value propositions). The cosine similarity values shown here are presented on a 1 to 10 scale, including only the values/links that are equal or greater than 2.

It is important to note that the relationships between different topics should not be considered in absolute terms. Rather, they should be seen as a way of using the semantic proximity of the topic-specific assertions to form the basis for shaping the VP development framework. The seven elements of this VP development framework and the resulting semantic links between them allowed us to two formulate two key insights, which we outline next.

5. Analysis of the Results

5.1. Three VP Elements Related to Customer Base Growth

A straightforward interpretation of the VP development framework shown in

Figure 3 suggests that there is a close interrelation between four core VP elements:

Stakeholder value propositions,

Foreign market entry,

Value created and

Customer base. Our claim about a closer interrelationship between these four core elements is based on the fact each of these elements relates to the other three.

Customer base appears as a natural dependent variable associated with the context of new growth-oriented companies. Our framework suggests that a company’s customer base is related to the efficiency of company’s value creation processes (i.e., its ability to access, combine and align resources provided by the key actors engaged in their business ecosystem; see assertions associated with

Value created [Topic 1] in

Appendix A), its foreign market entry strategy (i.e., its strategic plan to penetrate global market locations by transforming its local offers into global ones; see assertions associated with

Foreign market entry [Topic 3] in

Appendix A); and the attractiveness and alignment of its VPs in relation to key members of their business ecosystem (i.e., its ability to shape a VP portfolio in alignment with its scaling objectives; see assertions associated with

stakeholder value propositions [Topic 2] in

Appendix A). These findings are in line with some of the insights described in our literature review. The value of our suggested framework (

Figure 3) is in the way it structures the assertions/actionable insights around specific topics and its explicit identification of the interrelation between four core VP development elements in the context of new companies.

5.2. VP Development Is a Continuously Improved Process

Our VP framework suggests that a company’s C

ustomer base growth is continuously enhanced through a positive loop enabled by activities focused on the

Continuous improvement of the

Value created, the alignment of

Stakeholder value propositions, and

Foreign market entry processes (see assertions associated with

Continuous improvement [Topic 5] in

Appendix A) and on the

Company image (see assertions associated this topic [Topic 7] in

Appendix A). This finding helps emphasize the dynamic nature of VP development activities among new companies. Our VP model also identifies an alignment between

Stakeholder value propositions and the knowledge-management learning emerging from

Cross-border operations (see assertions associated with this topic [Topic 6] in

Appendix A). This puts the

Stakeholder value propositions element in a central position and underlines its importance in terms of VP portfolio development and alignment in cross-border contexts. Interestingly, our topic modelling separates

Foreign market entry activities from

Cross-border operations activities, the latter focusing on managing knowledge flow and learning rather than foreign market development. The emergence of this distinction is an interesting finding that merits future study.

5.3. How AI-Driven Digitalization Can Enhance the VPs of New Companies Interested to Scale

Given our findings, we can now broach our central question: how can the VP development activities of new growth-oriented companies be enhanced or empowered by the adoption of AI resources and capabilities, i.e., by AI-driven digitalization? Our choice of criteria for the selection of specific assertions was based on the insights of Mishra and Pani (2020), Güngör (2020), Majhi et al. (2021), and Rogers (2016) about the capability of the activities described by these assertions to be enhanced by AI-driven digitalization, more specifically sensing and seizing opportunities and reconfiguring key business aspects related to customers, competition, data utilization, innovation, and value creation. These included:

automating business processes;

gaining decision-making insights through data analysis;

enhancing engagement or relationships with customers, employees, investors, partners and other relevant stakeholders;

identifying opportunities in the value chain from the adoption of a multi-stakeholder benefit analysis perspective;

building rich customer prospect profiles, enabling dynamic pricing, and automating workflows and post-order services;

uncovering new customer needs, business opportunities, and corresponding innovative offers.

The actionable insights selected for our analysis are shown in

Table 1 alongside specific potential benefits of enabling or enhancing them using AI. Their analysis is performed in keeping with our VP development framework model (

Figure 3). A preliminary observation arising from the assertions in

Table 1 might propose that AI-driven digitalization could indeed enhance VP development activities across all parts of the VP framework bringing us to attempt a quantitative comparison between degrees to which different VP elements could be enhanced. We do not, however, believe that our results allow for such straightforward comparison. Still, we posit being able to achieve valuable insights about overarching topics with the highest or lowest potential to be enhanced by AI-driven digitalization.

Based on

Table 1, we could claim that there is a clear potential for AI to enhance the four core elements of our VP model:

value created, stakeholder value propositions,

foreign market entry and

customer base (topics 1 to 4 respectively). More importantly, we find the greatest number of assertions related to activities that could be enhanced by AI under Topic 4 (

customer base), which is the one associated with scaling potential. We therefore see AI-driven digitalization as potentially most influential in shaping strategic activities focusing on growing a company’s customer base (a finding supported in Rogers, 2016).

The contents of

Table 1 also suggest that

Continuous improvement may be another VP element that could be enhanced by AI. Interestingly, this is the VP development element under which is folded the assertion that is strictly related to AI, i.e., using data and artificial intelligence to personalize offers to consumers. Our VP model shows that

Continuous improvement links

Stakeholder value propositions and

Value created via

Company image. Two of the most relevant assertions under

value created refer to the ability of firms to choose to combine their internal resources with those of other resource owners to create value they could not otherwise create on their own in the context of complying with all relevant cultural, legal, and regulatory norms. This speaks directly to the power of AI resources and capabilities to enable a company’s reconfiguring capacity (Majhi et al. 2021). The potential of AI in enabling a dynamic

Continuous improvement link between

Value created (reconfiguring capacity),

Stakeholder value propositions (business ecosystem alignment structure),

Foreign market entry (ability to address new global markets by using insights from successful local products and services) and companies’ scaling potential (

Customer base) is an important finding that should become the subject of future studies.

Another interesting finding is the seemingly central role of

Stakeholder value propositions (development and alignment) in both our VP framework and the set of activities that could be enhanced by AI-driven digitalization (

Table 1). Activities related to

Stakeholder value propositions appear to be uniquely related to

Cross-border operations in addition to their inherent relation with three of the four core VP elements,

Foreign market entry,

Value created, and

Customer base. These interrelationships are also part of the positive loop enabled by the

Continuous improvement VP element. Our analysis tells us that AI-driven digitalization can enable these interrelations.

Lastly, the fundamental value of our study results is that they provide specific, actionable insights for each VP development element which could prove valuable to practitioners working with new companies (see

Appendix A). Our results also offer an overview of activities that could be potentially enhanced by the adoption of AI-driven digitalization practices (

Table 1).

6. Conclusions

Based on the literature pertaining to AI-driven digitalization, AI-based business value, new company VP development, and business ecosystems, we generated a corpus of actionable insights and applied topic modelling to it to propose a VP development framework. The analysis of the results of the adopted topic modelling approach provides insights into how AI-driven digitalization could be used to enhance the VPs of new growth-oriented companies. Thus, the study makes a methodological contribution by demonstrating a way of applying topic modelling to turn research assertions into actionable insights for entrepreneurs and executive managers of new ventures.

We focused on new companies for two reasons. Firstly, the majority of new firms are faced with the challenges of scaling up. Though this challenge is not specific to unique countries or geographical regions, it is particularly relevant for Canadian firms in light of a recent report by the Toronto Board of Trade that states that “Canada is a terrific start-up nation but a dismal failure as a scale-up nation” (Crane 2019). Secondly, new companies fundamentally require a multi-stakeholder perspective on VP development. These companies must design and align a VP portfolio to all their relevant stakeholders including investors, suppliers, distributors, and partners rather than trying to address the needs of customers alone (Bailetti et al. 2020). Their unavoidable need to adopt a multi-stakeholder perspective offers practitioners an opportunity to contribute to VP research by enhancing the similar insights that were already made by scholars (Frow et al. 2014; Adner 2012; Jacobides et al. 2018).

The study of new companies is highly relevant for the majority of economic sectors worldwide and needs more attention by researchers. Our study establishes an explicit link between AI-driven digitalization and VP development as it pertains to new companies. The adoption of a multi-stakeholder perspective on the relationship between AI-driven digitalization and VP development speaks to the growing research interest in digital business transformation. The contribution of this perspective is primarily methodological. Our study appears to be the first to adopt a topic modelling approach to bring actionable insights to the fore for both scholars and practitioners interested in the potential of AI-driven digitalization in the development of competitive VPs.

This article sought to articulate actionable insights for the benefit of new companies. It is meant to contribute to an emerging stream in entrepreneurship research calling for a stronger focus on the development of actionable principles for practitioners. For example, Berglund et al. (2018) highlighted the need for a distinct body of knowledge around pragmatically oriented, actionable principles that could bridge the gap between the causal mechanisms of entrepreneurship theory and the complex realities of entrepreneurial practice. Our focus on actionable insights is ultimately an expression of our commitment to the cause of applied research articulated by Berglund et al. (2018) and Shepherd and Gruber (2021).

Appendix A. Topic Modelling Results (Including Most Frequent Words and Assertions)

- (1)

-

Topic 1 – VC — Value created (product, service, sale, investor, norm, scaling master plan, benefit, resource)

Identify and access resources that allow to scale at lower costs by creating benefits for the resource owners that they cannot create alone.

Allow resource owners to make money using your products and services.

Align value created from the combination and deployment of external resources with scaling master plan.

Combine company resources with those of other resource owners to create value that cannot be created by your company alone.

Make decisions on how to best deploy value-adding combinations of external and internal resources, while complying with all relevant cultural, legal, and regulatory norms.

Establish partnerships that increase the demand for and complement your products.

Enable your freelance workers to become world-class service providers.

Increase order fulfillment and delivery capacity through partnering with third-party service providers and acquiring drop-shipping facilities.

Provide investors with evidence that your business model and target market can generate enough sales for the company to be investable in.

Provide returns that leave the most important resource owners better off than what they would have if they had not engaged with you.

Simplify the complementarity of your company products and services.

Combine two or more resources to create value that exceeds the sum of the value created from each resource separately.

Provide vendors and suppliers with real-time analytics on sales required to boost their own operations efficiency, sales and profits.

Use company’s technical and knowledge expertise to develop prototypes that demonstrate the value of your products and services.

Demonstrate how your technology, knowledge and experience contribute to company’s scaling master plan.

Contribute to university research projects and enhance the academic and technical reputation of your team to ensure that your company’s proposed technological concept is valid.

Develop a compelling image of your future company and use it to convince investors to provide funding and resource owners to provide resources needed to scale.

- (2)

-

Topic 2 – SVP — Stakeholder value propositions (value proposition, vision, future, salesperson, path)

Instill a sense of purpose by articulating and pursuing a compelling vision for the company in the future.

Provide investors a compelling short-term financial VP and a vision of favourable medium- and long-term VPs.

Develop VPs that enhance employee satisfaction, psychological attachment, and behavioural commitment to your company.

Continuously improve VPs based on results and feedback.

Learn from VPs of companies that have scaled early, rapidly, and securely, and use them to differentiate your company on the market.

Track changes in stakeholders’ VPs and use the information to realign your VPs to them.

Develop VPs for key members of the value chain that align with key members’ VPs and improve the competence of the value chain.

Develop VPs that enhance your customers’ and suppliers’ outcomes, marketing strategies, and competitive advantages.

Develop investor VPs describing the path to return on investment in return for investors’ funds and confidence.

- (3)

-

Topic 3 – FME — Foreign market entry (local, prototype, alliance, patent, regulation)

Develop a replicable formula to repeat what worked in one location in other locations.

Promote company’s achievements to date, e.g., awards, high-profile endorsements from established companies, sales, successful alliances and interactions with potential customers, strength of company’s scaling mater plan and the company’s potential to create local jobs, contributions to social causes, and advancement of knowledge.

Enable locals in other locations to succeed because of your company.

Enter a different geographical market by partnering with or purchasing local companies.

Improve links, interactions, and shared purpose with locals in each region the company operates in.

To globalize a local product, develop core product that can be readily disseminated worldwide.

Integrate local innovation into global themes, products, and services.

Include local actors into your global communication system and learn from multiple local experiences.

- (4)

-

Topic 4 – CB — Customer base (customer, stakeholder, user, supplier, loyalty, referral)

Apply big data analytics to produce insightful information about users, suppliers and customers to enhance shopping pattern analysis, improve customer experience, predict market trends, provide more secure online payment solutions, increase personalization, optimize and automate pricing, and provide dynamic customer service.

Attract traffic and new customers by targeting and retargeting users from search engines, referrals, adds and social media.

Engage customers to produce testimonials, reviews and ratings that help new customers to make purchasing decisions with knowledge of other customers experiences.

Provide rewards that satisfy customer needs for recognition of their loyalty.

Continuously improve user interfaces and applications that directly influence the entirety of customer experience including personalized content, quality messaging, and the delivery and returns process.

Implement a stakeholder-centric approach to satisfy stakeholder expectations in all markets.

Automatically extract the information a user, customer, investor, or stakeholder wants from the vast amount of the available information.

Build internet-based capabilities to acquire and retain customers during the initial stages of company’s life cycle.

Define the ideal target customer profiles and engage them relentlessly.

Use an end-to-end solution that links procurement directly with end customers to eliminate or reduce inventory and the number of intermediaries between the company and customers.

Enable employees, customers, users, investors, and other relevant parties to automatically extract information from company data for the purpose of decreasing costs and adding value to other stakeholders.

Establish trust and positive rapport with your customers that lead to long-term, mutually beneficial business relationships.

Adjust to your customers’ moods and work to find common ground to build familiarity.

Listen to your customers, take their feedback seriously, and adjust operations as needed.

Digitize as much of your company as you can to create value for customers, reduce costs, and increase security.

Deliver better performance on the metrics that customers care about.

- (5)

-

Topic 5 – CI — Continuous improvement (offer, channel, artificial intelligence, threshold, value chain, data)

Continuously improve individuals, operations, and infrastructures to advance and deliver a portfolio of innovative offers.

Apply processes that make offers easier to understand, produce and deliver.

Invest to improve cybersecurity of the value chain.

Expand information about the company, its offers, its achievements, and its affiliations.

Apply processes that continuously improve the cybersecurity of the company as well as its offers, channels, and resources.

Adapt offers to each market.

Provide a variety of complementary offers to each market.

Sell online using a variety of online and offline promotional channels.

Sell offers the target market perceives better than relevant alternatives.

Strengthen cybersecurity attributes of offers compared to competitors.

Use scientific and technological advances to develop innovative offers.

Broaden company offers to address more customer jobs to be done.

Unbundle the value chain and the jobs to be done within it to outsource lower value tasks to freelance workers and perform higher value tasks internally.

Use data and artificial intelligence to personalize offers to consumers.

- (6)

-

Topic 6 – CBO — Cross-border operations (community, founder, regulation, cross border)

Attain positions in cross-border networks which provide access to privileged information.

Build operational cross-border capabilities early.

Coordinate, evaluate and share knowledge between headquarters, cross-border units and among the units themselves.

Simultaneously develop global learning capabilities, cross-border flexibility, and global competitiveness.

Build a community where each member supports others rather than building many separate businesses.

Contribute to the creation of public goods such as open source code, standards, and test beds.

- (7)

-

Topic 7 – IMG — Company image (brand, identity, competitor, competition, ecommerce, price)

Create a unique brand identity to differentiate from the competition.

Expand brand coverage and eliminate intermediaries.

Brand the company and build a brand that has a strong market presence.

Select and retain a consistent identity for the multiple audiences with which you interact.

Deploy efficient ecommerce technologies and automation to reduce company costs and lower prices of offers.

Sell high quality offers at lower prices compared to competitors.

References

- Adner R (2017) Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy. Journal of Management 43(1), 39–58. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal A, Gans J and Goldfarb A (2018). Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence. Harvard Business Review Press. See also: Agrawal A, Gans J and Goldfarb A (2018) A simple tool to start making decisions with the help of AI. Harvard Business Review Online. https://hbr.org/2018/04/a-simple-tool-to-start-making-decisions-with-the-help-of-ai. Accessed 3 April 2021.

- Akemu O, Whiteman G and Kennedy S (2016) Social enterprise emergence from social movement activism: The Fairphone case. Journal of Management Studies 53(5):846–877. [CrossRef]

- Akter S, Michael K, Uddin M, McCarthy G and Rahman M (2020) Transforming business using digital innovations: the application of AI, blockchain, cloud and data analytics. Annals of Operations Research. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi R and Alfalqi K. (2015) A survey of topic modeling in text mining. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications (IJACSA), 6(1): 147-153. [CrossRef]

- Amit R and Zott C (2021) Business Model Innovation Strategy. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey.

- Anandarajan M, Hill C and Nolan T (2019) Semantic Space Representation and Latent Semantic Analysis. Ch. 6 in: Practical Text Analytics. Maximizing the Value of Text Data. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, pp 77-92.

- Anderson J, Narus J, Van Rossum W (2006) Customer VPs in business markets. Harvard Business Review 84(3):91–99.

- Bailetti T, Tanev S, and Keen C (2020) What Makes Value Propositions Distinct and Valuable to New Companies Committed to Scale Rapidly? Technology Innovation Management Review 10(6):14-27. [CrossRef]

- Bailetti T and Tanev S (2020) Examining the Relationship Between Value Propositions and Scaling Value for New Companies. Technology Innovation Management Review 10(2):5–13. [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre B, Calabretta G, Bocken N, and Jaskiewicz T (2017). Bridging sustainable business model innovation and user-driven innovation: A process for sustainable value proposition design. Journal of Cleaner Production 147:175–186. [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne D, Frow P, Varey R and Payne A (2011) VPs as communication practice: Taking a wider view. Industrial Marketing Management, 40:202–210. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, CY (2015) Bottlenecks, modules and dynamic architectural capabilities. Harvard Business School Finance Working Paper No. 15-028. [CrossRef]

- Berglund H, Dimov D and Wennberg K (2018) Beyond bridging rigor and relevance: The three-body problem in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 9:87–91. [CrossRef]

- Blei D (2012) Probabilistic Topic Models. Communications of the ACM 55(4):77–84. [CrossRef]

- Bocken N and Snihur Y (2020) Lean Startup and the business model: Experimenting for novelty and impact. Long Range Planning 53(4):101953. [CrossRef]

- Boyd-Graber J, Mimno D and Newman D (2014) Care and Feeding of Topic Models: Problems, Diagnostics, and Improvements. In: Airoldi EM, Blei D, Erosheva E and Fienberg S, (Eds) Handbook of Mixed Membership Models and Its Applications. Chapman and Hall/CRC, New York pp. 225–254.

- Brandenburger A and Stuart Jr H (1996) Value-based Business Strategy. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 5(1):5–24. [CrossRef]

- Buccieri D, Javalgi RG and Cavusgil E (2020) International new venture performance: Role of international entrepreneurial culture, ambidextrous innovation, and dynamic marketing capabilities. International Business Review 29(2): 101639. [CrossRef]

- Burström T, Parida V, Lahti T and Wincent J (2021) AI-enabled business-model innovation and transformation in industrial ecosystems: A framework, model and outline for further research. Journal of Business Research 127: 85–95. [CrossRef]

- Bussgang J and Stern O (2015) How Israeli startups can scale. Harvard Business Review, September Issue.

- Caputo A, Pizzi S, Pellegrini M and Dabić M (2021) Digitalization and business models: Where are we going? A science map of the field. Journal of Business Research 123:489–501. [CrossRef]

- Casali G, Perano M, Presenza A and Abbate T (2018) Does innovation propensity influence wineries’ distribution channel decisions? International Journal of Wine Business Research 30(4):446–462. [CrossRef]

- Copeland BJ (2019) Artificial intelligence. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved online: https://www.britannica.com/technology/artificial-intelligence. Accessed: 15 January 2022.

- Corvellec H and Hultman J (2014) Managing the politics of value propositions. Marketing Theory 14(4):355–375. [CrossRef]

- Crane D (2019) It’s time for Canada to focus on the scale-up challenge. IT World Canada https://www.itworldcanada.com/article/its-time-for-canada-to-focus-on-the-scale-up-challenge/420027 Accessed: 08 10 22.

- Dattée B, Alexy O and Autio E (2018) Maneuvering in Poor Visibility: How Firms Play the Ecosystem Game when Uncertainty is High. Academy of Management Journal 61(2):466–498. [CrossRef]

- Davenport T and Ronanki R (2018) Artificial Intelligence for the Real World. Harvard Business Review, January–February:2–10.

- Dong JQ and Yang C-H (2020) Business Value of Big Data Analytics: A Systems-Theoretic. Approach and Empirical Test. Information & Management 57(1):103-124. [CrossRef]

- Eisenmann TR (2013) Entrepreneurship: A working definition. Harvard Business Review 10.

- Eggert et al. (2018) Conceptualizing and communicating value in business markets: From value in exchange to value in use. Industrial Marketing Management, 69:80–90. [CrossRef]

- Frow P, McColl-Kennedy J, Hilton T, Davidson A, Payne A and Brozovic D (2014) Value propositions: A service ecosystems perspective. Marketing Theory 14(3):327–351. [CrossRef]

- Frow P and Payne A (2011) A stakeholder perspective of the value proposition concept. European Journal of Marketing, 45(1/2):223–240.

- Girotra K and Netessine S (2013) OM Forum—Business Model Innovation for Sustainability. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 15(4):537–544.

- Grönroos C (2011) A service perspective on business relationships: The value creation, interaction and marketing interface. Industrial Marketing Management 40(2):240–247. [CrossRef]

- Güngör H (2020) Creating Value with Artificial Intelligence: A Multi-stakeholder Perspective. Journal of Creating Value 6(1):72–85. [CrossRef]

- Hannigan T, Haans R, Vakili K, Tchalian H, Glaser V, Wang M, Kaplan S and Jennings P (2019) Topic Modeling in Management Research: Rendering New Theory from Textual Data. Academy of Management Annals 13(2):586–632. [CrossRef]

- Holttinen H (2014) Contextualizing value propositions: Examining how consumers experience value propositions in their practices. Australasian Marketing Journal 22:103–110. [CrossRef]

- Huang M-H and Rust R (2021) Engaged to a Robot? The Role of AI in Service. Journal of Service Research 24(1): 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Iansiti M and Lakhani K (2014) Digital ubiquity: How connections, sensors, and data are revolutionizing business. Harvard Business Review 92(11):90–99.

- Jacobides MG, Cennamo C and Gawer A (2018) Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strategic Management Journal 39(8):2255–2276. [CrossRef]

- Kerzel U (2021) Enterprise AI Canvas Integrating Artificial Intelligence into Business. Applied Artificial Intelligence 35(1):1–12. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2009.11190.pdf.

- Kier A and McMullen J (2018) Entrepreneurial imaginativeness in new venture ideation. Academy of Management Journal 61(6): 2265–2295. [CrossRef]

- Kollmann T, Stöckmann C and Kensbock JM (2017) Fear of failure as a mediator of the relationship between obstacles and nascent entrepreneurial activity—An experimental approach. Journal of Business Venturing 32(3):280–301. [CrossRef]

- Kothandaraman P and Wilson D (2001) The future of competition: Value-creating networks. Industrial Marketing Management 30(4):379–389. [CrossRef]

- Kraus S, Jones P, Kailer N, Weinmann A, Chaparro-Banegas N and Roig-Tierno N (2021) Digital Transformation: An Overview of the Current State of the Art of Research. SAGE Open, July-September: 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Kraus S, Clauss T, Breier M, Gast J, Zardini A and Tiberius V (2020) The economics of COVID-19: initial empirical evidence on how family firms in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 26(5):1067–1092. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen HS and Remmen A (2019) A framework for sustainable value propositions in product-service systems. Journal of cleaner production 223:25–35. [CrossRef]

- Kump B, Engelmann A, Kessler A and Schweiger C (2019) Toward a dynamic capabilities scale: measuring organizational sensing, seizing, and transforming capacities. Industrial and Corporate Change 28(5):1149–1172. [CrossRef]

- Langlois RN (2003) The vanishing hand: the changing dynamics of industrial capitalism. Industrial and corporate change, 12(2):351–385. [CrossRef]

- Lanning M (2000) Delivering profitable value: A revolutionary framework to accelerate growth, generate wealth, and rediscover the heart of business. Perseus Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Lanning M and Michaels E (1988) A business is a value delivery system. McKinsey Staff Paper 41(June):1–16.

- Latilla V, Urbinati A, Cavallo A, Franzò S and Ghezzi A (2020) Organizational re-design for business model innovation while exploiting digital technologies: a single case study of an energy company. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 2040002. [CrossRef]

- Lu Q & Chesbrough H (2022) Measuring open innovation practices through topic modelling: Revisiting their impact on firm financial performance. Technovation 114: 102434. [CrossRef]

- Majhi SG, Mukherjee A and Anand A (2021) Business value of cognitive analytics technology: a dynamic capabilities perspective. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems (ahead-of-print publication). [CrossRef]

- Makadok R, Burton R and Barney J (2018) A practical guide for making theory contributions in strategic management. Strategic Management Journal 39(6):1530–1545. [CrossRef]

- Malnight T, Buche I and Dhanaraj Ch (2019) Put Purpose at the CORE of Your Strategy. Harvard Business Review 97(5):70–78.

- Mishra A and Pani A (2020) Business value appropriation roadmap for artificial intelligence. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems 51(3):2059–5891. [CrossRef]

- Mishra S, Ewing MT and Pitt LF (2019) The effects of an articulated customer value proposition (CVP) on promotional expense, brand investment and firm performance in B2B markets: A text based analysis. Industrial Marketing Management 87:264–275. [CrossRef]

- Nambisan S, Zahra S and Luo Y (2019) Global platforms and ecosystems: Implications for international business theories. Journal of International Business Studies 50(9):1464–1486. [CrossRef]

- Nenonen S, Storbacka K, Sklyar A, Frow P and Payne A (2019) Value propositions as market-shaping devices: A qualitative comparative analysis. Industrial Marketing Management 87:276–290. [CrossRef]

- Nenonen S, Storbacka K and Windahl C (2019) Capabilities for market-shaping: triggering and facilitating increased value creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 47(4):617–639. [CrossRef]

- Ng I and Wakenshaw S (2017) The internet-of-things: Review and research directions. International Journal of Research in Marketing 34(1):3–21. [CrossRef]

- Niemand T, Coen Rigtering JP, Kallmünzer A, Kraus S and Maalaoui A (2021) Digitalization in the financial industry: A contingency approach of entrepreneurial orientation and strategic vision on digitalization. European Management Journal 39(3):317–326. [CrossRef]

- Onetti A, Zucchella A, Jones M and McDougall-Covin P (2012) Internationalization, innovation and entrepreneurship: business models for new technology-based firms. Journal of Management & Governance 16:337–368. [CrossRef]

- Paschen J, Wilson M and Ferreira J (2020) Collaborative intelligence: How human and artificial intelligence create value along the B2B sales funnel. Business Horizons 63:403–414. [CrossRef]

- Payne A, Frow P, Steinhoff L and Eggert A (2020) Toward a comprehensive framework of value proposition development: From strategy to implementation. Industrial Marketing Management 87:244–255. [CrossRef]

- Payne A, Frow P and Eggert A (2017) The customer value proposition: evolution, development, and application in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 45(4):467–489. [CrossRef]

- Rogers D (2016) The Digital Transformation Playbook - Rethink Your Business for the Digital Age. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Rydehell H, Löfsten H and Isaksson A (2018) Novelty-oriented value propositions for new technology-based companies: Impact of business networks and growth orientation. The Journal of High Technology Management Research 29(2):161–171. [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy S and Dew N (2005) New market creation through transformation. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 15(5):533–565. [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy SD (2001) Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review 26(2):243–263. [CrossRef]

- Schallmo D and Tidd J (2021) Digitalization: Approaches, Case Studies, and Tools for Strategy, Transformation and Implementation. Series on Management for Professionals, Springer, New York.

- Schepis D (2020) How innovation intermediaries support start-up internationalization: a relational proximity perspective. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 36(11): 2062-2073. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian I, Ross J, Beath C, Mocker M, Moloney K and Fonstad N (2017). How big old companies navigate digital transformation. MIS Quarterly Executive 16(3):197–213.

- Shane S and Venkataraman S (2000) The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review 25(1):217–226. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd D and Gruber M (2021) The Lean Startup Framework: Closing the Academic–Practitioner Divide. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 45(5):967–998. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd D, Souitaris V and Gruber M (2020) Creating New Ventures: A Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Management, 47(1):11–42. [CrossRef]

- Singh A and Hess T (2017) How chief digital officers promote the digital transformation of their companies. MIS Quarterly Executive 16(1):1–17.

- Sjödin D, Parida V, Palmié M and Wincent J (2021) How AI capabilities enable business model innovation: Scaling AI through co-evolutionary processes and feedback loops. Journal of Business Research, 134:574–587. [CrossRef]

- Skålén P, Gummerus J, von Koskull , and Magnusson P (2015) Exploring value propositions and service innovation: A service-dominant logic study. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43(2):137–158. [CrossRef]

- Soluk J, Miroshnychenko I, Kammerlander N and De Massis A (2021) Family Influence and Digital Business Model Innovation: The Enabling Role of Dynamic Capabilities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 45(4):867–905. [CrossRef]

- Stam E and van de Ven A (2019) Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Business Economics, #:1–24. [CrossRef]

- Tanev S, Bailetti T, Keen C and Hudson D (2022) The Potential of AI to Enhance the Value Propositions of New Companies Committed to Scale Early and Rapidly. Ch. 9 in: Tanev S and Blackbright H (Eds) Artificial Intelligence and Innovation Management (Series on Technology Management), World Scientific, pp. 185–213. [CrossRef]

- Teece D (2007) Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and micro foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal 28(13):1319–1350. [CrossRef]

- Thakral P, Sharma D and Ghosh K (2024) Evidence-based knowledge management: a topic modeling analysis of research on knowledge management and analytics. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, ahead-of-print. https://doi-org.proxy.library.carleton.ca/10.1108/VJIKMS-03-2023-0079.

- Tidd J (2019) Digital Disruptive Innovation. Series on Technology Management, 36, World Scientific.

- Truong Y, Simmons G, Palmer M (2012) Reciprocal value propositions in practice: Constraints in digital markets. Industrial Marketing Management 41(1):197–206. [CrossRef]

- Verhoef P, Broekhuizen T, Bart Y, Bhattacharya A, Qi Dong J, Fabian N and Haenlein M (2021) Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. Journal of Business Research 122:889–901. [CrossRef]

- Wagner DN (2020) The nature of the Artificially Intelligent Firm - An economic investigation into changes that AI brings to the firm. Telecommunications Policy 44(6):101954. [CrossRef]

- Webster F (2002) Market-driven management: How to define, develop and deliver customer value (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey.

- Wedel M and Kannan P (2016) Marketing analytics for data-rich environments. Journal of Marketing 80(6):97–121. [CrossRef]

- Weill P and Woerner S (2015) Thriving in an Increasingly Digital Ecosystem. MIT Sloan Management Review 56(4):27–34.

- Westerman G, Calméjane C, Bonnet D, Ferraris P and McAfee A (2011) Digital Transformation: A roadmap for billion-dollar organizations. MIT Center for Digital Business and Capgemini Consulting 1:1-68.

- Winter S (2003) Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal 24(10):991–995.

- Wouters M, Anderson J and Kirchberger M (2018) New-Technology Startups Seeking Pilot Customers: Crafting a Pair of VPs. California Management Review 60(4):101–124. [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki J (2020) Introducing the AI Project Canvas. Medium.

- https://towardsdatascience.com/introducing-the-ai-project-canvas-e88e29eb7024, Accessed: Feb 29, 2024.

- Zhang J, Lichtenstein Y and Gander J (2015) Designing scalable digital business model. Business models and modelling. Advances in Strategic Management 33: 241–277.

- Zott C, Amit R and Massa L (2011) The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of Management 37(4): 1019–1042. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).