Submitted:

10 March 2024

Posted:

11 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

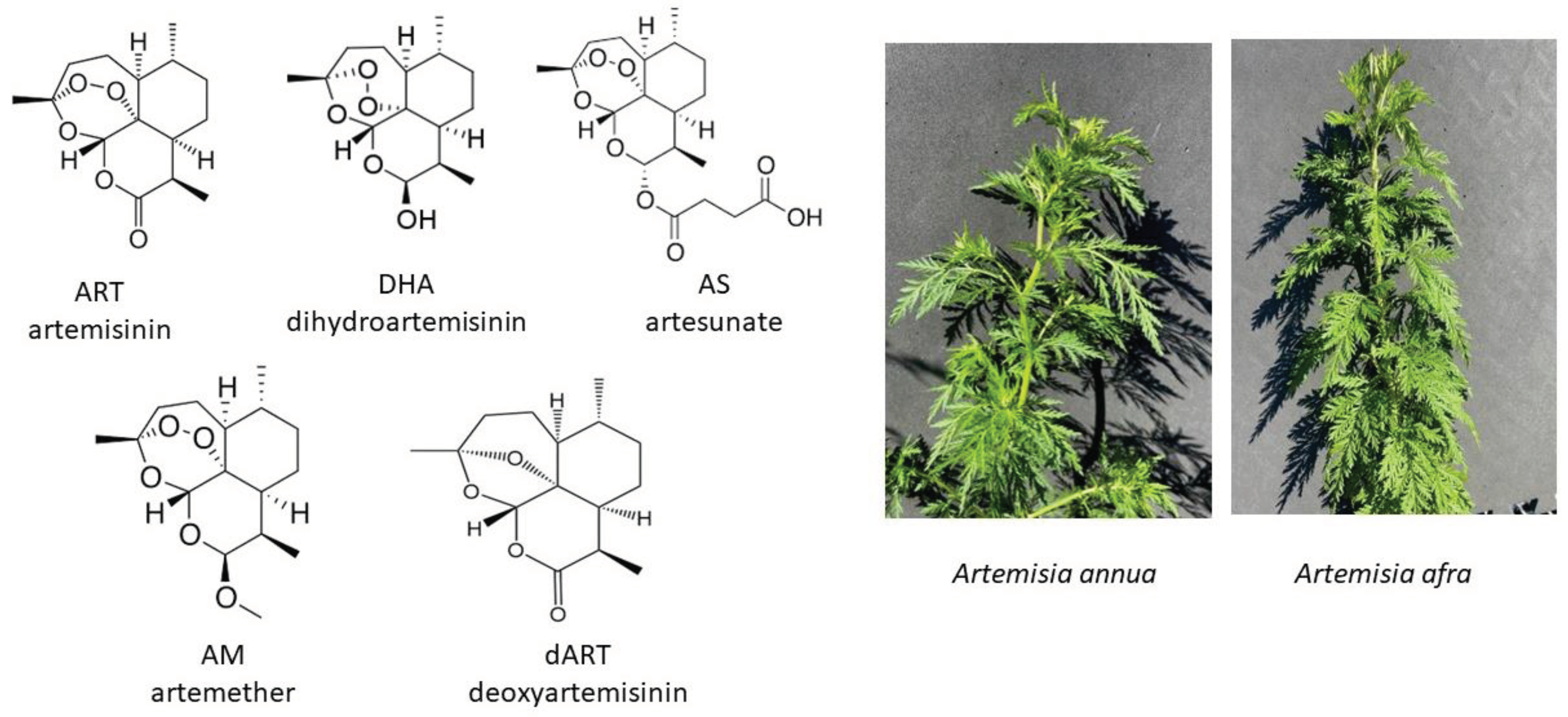

1. Introduction

2. Results

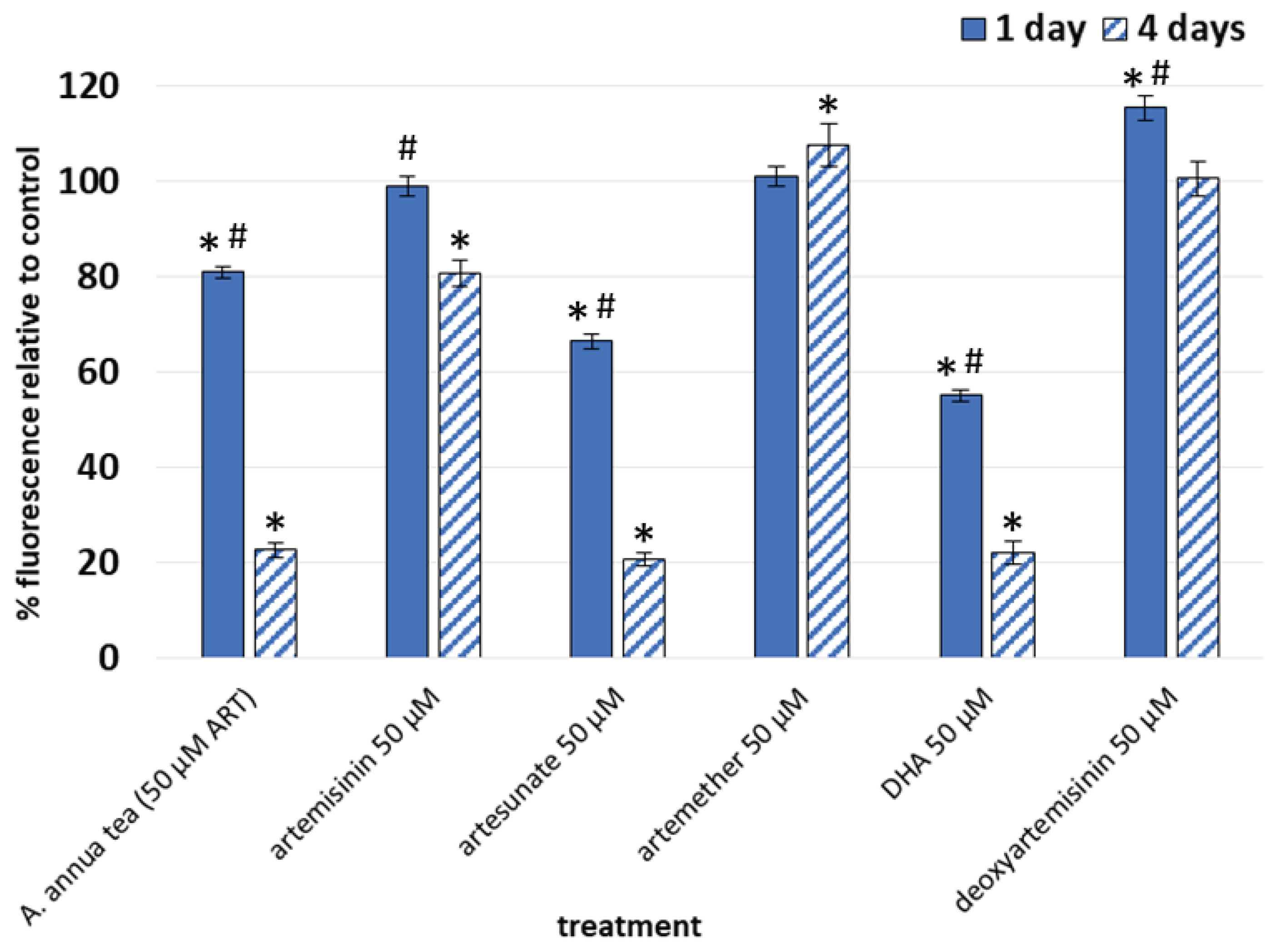

2.1. Differential Effects of Artemisia Teas vs. ART Drugs on Human Dermal Fibroblast Viability

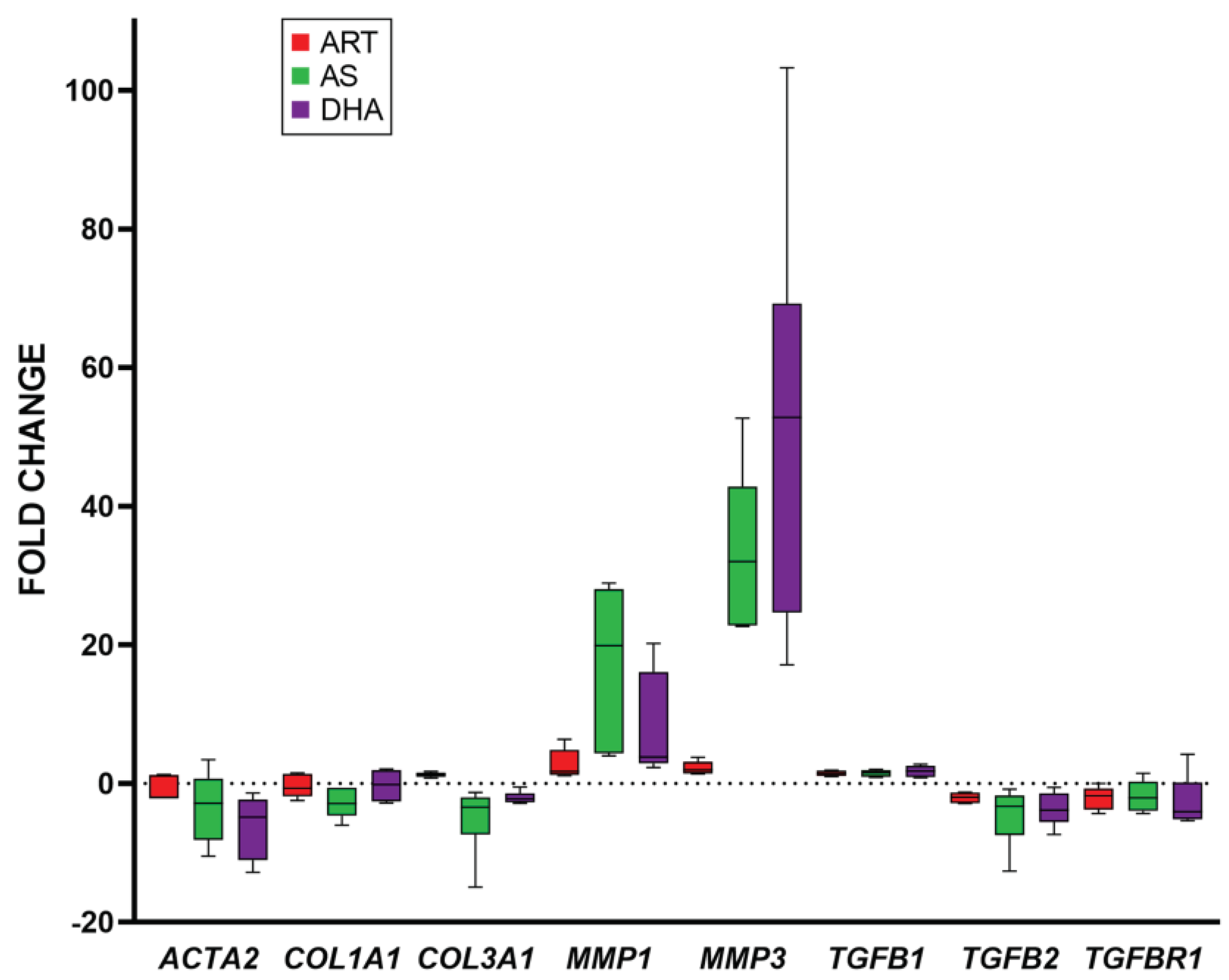

2.2. Differential Expression of Fibrotic Genes in ART Drug Treated Fibroblasts

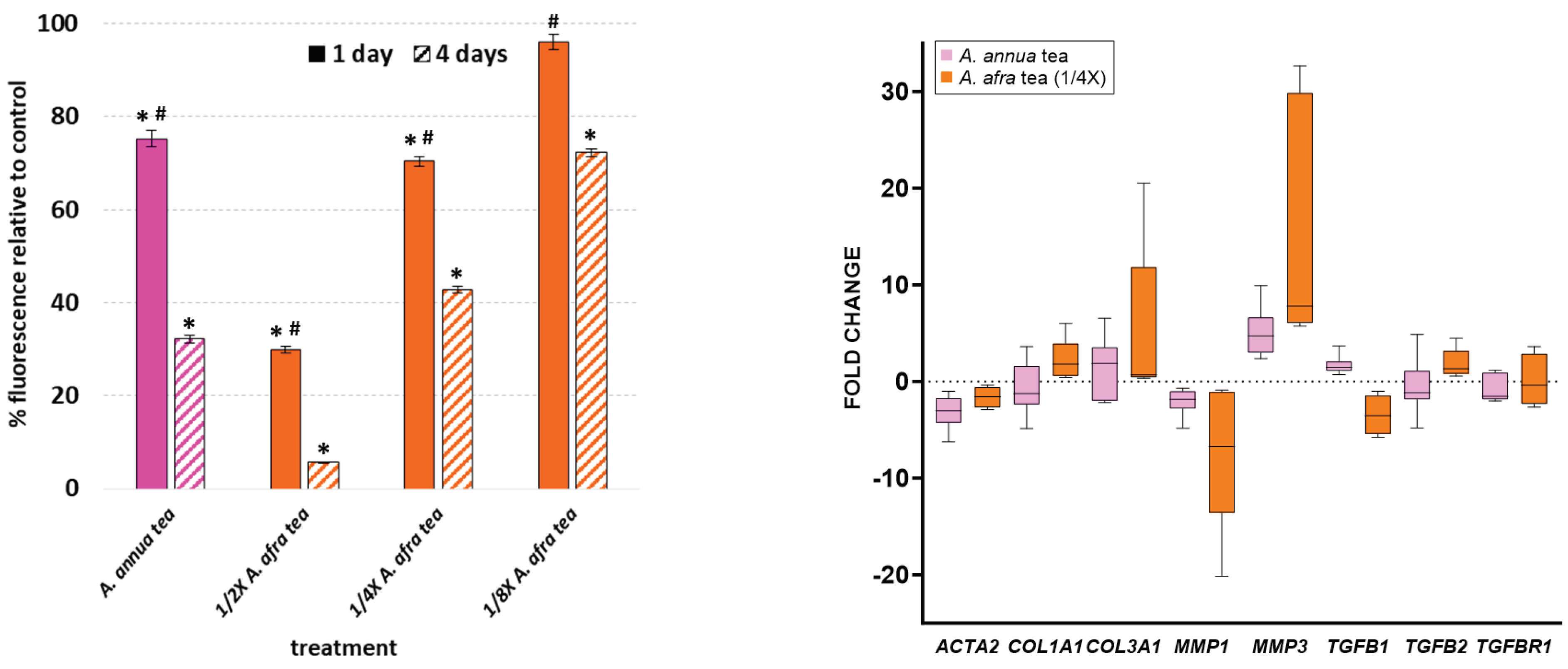

2.3. A. afra vs. A. annua.

2.4. Differential Expression of α-SMA Protein after 1 and 4 days of ART, ART Drugs and Artemisia Treatments in Fibroblasts

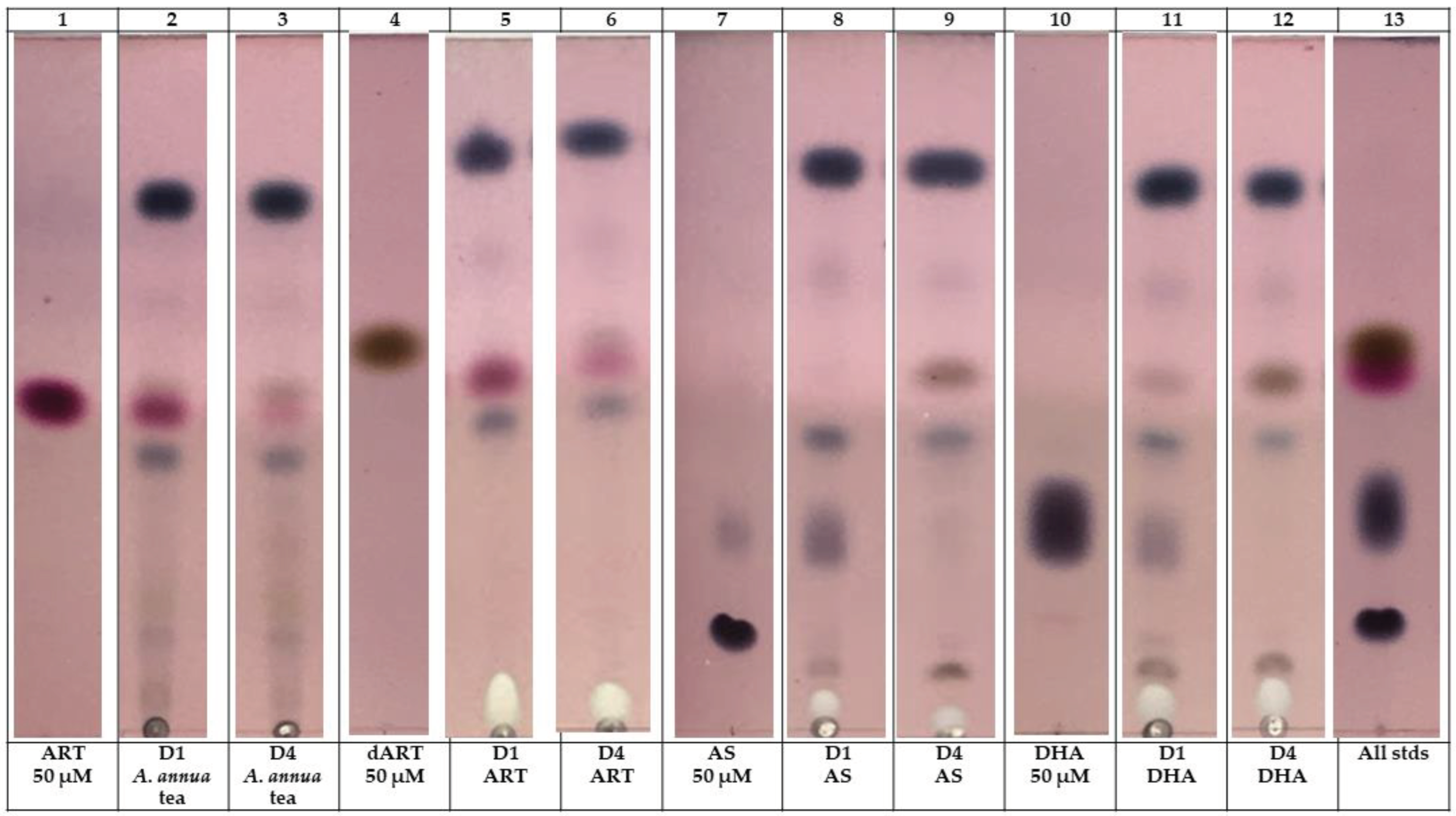

2.5. A. annua, ART, and ART Drugs Show Bioconversion in Culture Medium after 4 d Incubation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biological Materials

4.2. Drug Treatments

4.3. Resazurin Assay

4.4. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.5. Immunocytochemistry

4.6. Analysis of Artemisinic Metabolites in Media

4.7. Sample Sizes and Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Wynn, T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland 2008, 214, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, J.; Duffy, H.S. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts: what are we talking about? Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology 2011, 57, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, B. Myofibroblasts. Experimental eye research 2016, 142, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolivo, D.M.; Larson, S.A.; Dominko, T. Crosstalk between mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors and transforming growth factor-β signaling results in variable activation of human dermal fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 43, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynn, T.A. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.K.; Sheppard, D.; Chapman, H.A. TGF-β1 signaling and tissue fibrosis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2018, 10, a022293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.E. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-β signaling. Cell Res. 2009, 19, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolivo, D.M.; Larson, S.A.; Dominko, T. FGF2-mediated attenuation of myofibroblast activation is modulated by distinct MAPK signaling pathways in human dermal fibroblasts. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 88, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, N.C.; Rieder, F.; Wynn, T.A. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature 2020, 587, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efferth, T. Artemisinin: a versatile weapon from traditional Chinese medicine. In Herbal drugs: ethnomedicine to modern medicine; Springer: 2009; pp. 173–194.

- Naß, J.; Efferth, T. The activity of Artemisia spp. and their constituents against Trypanosomiasis. Phytomedicine 2018, 47, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, B.H.; Alonso, M.N.; Weathers, P.J.; Shell, S.S. Artemisia afra and Artemisia annua Extracts Have Bactericidal Activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Physiologically Relevant Carbon Sources and Hypoxia. Pathogens 2023, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, M.C.; Zhang, T.; Williams, J.T.; Abramovitch, R.B.; Weathers, P.J.; Shell, S.S. Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra extracts exhibit strong bactericidal activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 262, 113191–113191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Williams, J.T.; Aleiwi, B.; Ellsworth, E.; Abramovitch, R.B. Inhibiting Mycobacterium tuberculosis DosRST Signaling by Targeting Response Regulator DNA Binding and Sensor Kinase Heme. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efferth, T. Beyond malaria: The inhibition of viruses by artemisinin-type compounds. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, M.R.; Efferth, T.; Serrano, M.A.; Castaño, B.; Macias, R.I.; Briz, O.; Marin, J.J. Effect of artemisinin/artesunate as inhibitors of hepatitis B virus production in an “in vitro” replicative system. Antivir. Res. 2005, 68, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, M.; Huang, Y.; Fidock, D.; Polyak, S.; Wagoner, J.; Towler, M.; Weathers, P. Artemisia annua L. extracts inhibit the in vitro replication of SARS-CoV-2 and two of its variants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 274, 114016–114016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Gilmore, K.; Ramirez, S.; Settels, E.; Gammeltoft, K.A.; Pham, L.V.; Fahnøe, U.; Feng, S.; Offersgaard, A.; Trimpert, J.; et al. In vitro efficacy of artemisinin-based treatments against SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abba, M.L.; Patil, N.; Leupold, J.H.; Saeed, M.E.; Efferth, T.; Allgayer, H. Prevention of carcinogenesis and metastasis by Artemisinin-type drugs. Cancer Lett. 2018, 429, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolivo, D.; Weathers, P.; Dominko, T. Artemisinin and artemisinin derivatives as anti-fibrotic therapeutics. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 11, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, S.A.; Dolivo, D.M.; Dominko, T. Artesunate inhibits myofibroblast formation via induction of apoptosis and antagonism of pro-fibrotic gene expression in human dermal fibroblasts. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; You, F.; Xue, J. Novel use for old drugs: The emerging role of artemisinin and its derivatives in fibrosis. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 157, 104829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruessner, B.M.; Cornet-Vernet, L.; Desrosiers, M.R.; Lutgen, P.; Towler, M.J.; Weathers, P.J. It is not just artemisinin: Artemisia sp. for treating diseases including malaria and schistosomiasis. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 1509–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, P.J. Artemisinin as a therapeutic vs. its more complex Artemisia source material. Natural Product Reports 2023.

- Nie, C.; Trimpert, J.; Moon, S.; Haag, R.; Gilmore, K.; Kaufer, B.B.; Seeberger, P.H. In vitro efficacy of Artemisia extracts against SARS-CoV-2. Virol J 2021, 18, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrosiers, M.R.; Mittleman, A.; Weathers, P.J. Dried Leaf Artemisia Annua Improves Bioavailability of Artemisinin via Cytochrome P450 Inhibition and Enhances Artemisinin Efficacy Downstream. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.; Stebbings, S.; McNamara, D. An open-label six-month extension study to investigate the safety and efficacy of an extract of Artemisia annua for managing pain, stiffness and functional limitation associated with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. . 2016, 129, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stebbings, S.; Beattie, E.; McNamara, D.; Hunt, S. A pilot randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of an extract of Artemisia annua administered over 12 weeks, for managing pain, stiffness, and functional limitation associated with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015, 35, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Guo, M.-Y.; Luo, Y.; Yun, M.-D.; Yan, J.; Liu, T.; Xiao, C.-H. Effect of Artemisia annua extract on treating active rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2016, 23, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faveri Favero, F.; Grando, R.; Nonato, F.R.; Sousa, I.M.; Queiroz, N.C.; Longato, G.B.; Zafred, R.R.; Carvalho, J.E.; Spindola, H.M.; Foglio, M.A. Artemisia annua L. : evidence of sesquiterpene lactones’ fraction antinociceptive activity. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2014, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dehkordi, F.M.; Kaboutari, J.; Zendehdel, M.; Javdani, M. The antinociceptive effect of artemisinin on the inflammatory pain and role of GABAergic and opioidergic systems. Korean J. Pain 2019, 32, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Kim, S.-M.; Nam, G.E.; Kim, S.-H.; Park, S.-J.; Park, Y.-K.; Baik, H.W. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multi-Centered Clinical Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Artemisia annua L. Extract for Improvement of Liver Function. Clinical Nutrition Research 2020, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Yin, H.; Wang, J.; He, D.; Yan, Q.; Lu, L. Dihydroartemisinin alleviates skin fibrosis and endothelial dysfunction in bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis models. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 4269–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nong, X.; Rajbanshi, G.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, T.; Chen, S.; Wei, G.; Li, J. Effect of artesunate and relation with TGF-β1 and SMAD3 signaling on experimental hypertrophic scar model in rabbit ear. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2019, 311, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poswal, F.S.; Russell, G.; Mackonochie, M.; MacLennan, E.; Adukwu, E.C.; Rolfe, V. Herbal Teas and their Health Benefits: A Scoping Review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2019, 74, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efferth, T.; Benakis, A.; Romero, M.R.; Tomicic, M.; Rauh, R.; Steinbach, D.; Häfer, R.; Stamminger, T.; Oesch, F.; Kaina, B.; et al. Enhancement of cytotoxicity of artemisinins toward cancer cells by ferrous iron. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wong, Y.-K.; Shen, S.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, J. Advances in the research on the targets of anti-malaria actions of artemisinin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 216, 107697–107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunajeewa, H.A. Artemisinins: artemisinin, dihydroartemisinin, artemether and artesunate. Treatment and prevention of malaria: antimalarial drug chemistry, action and use 2012, 157-190.

- Wang, J.; Zhang, C.-J.; Ni Chia, W.; Loh, C.C.Y.; Li, Z.; Lee, Y.M.; He, Y.; Yuan, L.-X.; Lim, T.K.; Liu, M.; et al. Haem-activated promiscuous targeting of artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gashe, F.; Wynendaele, E.; De Spiegeleer, B.; Suleman, S. Degradation kinetics of artesunate for the development of an ex-tempore intravenous injection. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Morris, C.; Duparc, S.; Borghini-Fuhrer, I.; Jung, D.; Shin, C.-S.; Fleckenstein, L. Review of the clinical pharmacokinetics of artesunate and its active metabolite dihydroartemisinin following intravenous, intramuscular, oral or rectal administration. Malar. J. 2011, 10, 263–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuidenhout, J.W.; Aucamp, M.; Stieger, N.; Liebenberg, W.; Haynes, R.K. Assessment of Thermal and Hydrolytic Stabilities and Aqueous Solubility of Artesunate for Formulation Studies. Aaps Pharmscitech 2023, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbergen, R.; Oti, M.; ter Horst, R.; Tat, W.; Neufeldt, C.; Belovodskiy, A.; Chua, T.T.; Cho, W.J.; Joyce, M.; Dutilh, B.E.; et al. Establishing normal metabolism and differentiation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by culturing in adult human serum. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Transforming growth factor–β in tissue fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walraven, M.; Hinz, B. Therapeutic approaches to control tissue repair and fibrosis: Extracellular matrix as a game changer. Matrix Biol. 2018, 71-72, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrosiers, M.R.; Weathers, P.J. Effect of leaf digestion and artemisinin solubility for use in oral consumption of dried Artemisia annua leaves to treat malaria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 190, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrosiers, M.R.; Towler, M.J.; Weathers, P.J. Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra Essential Oils and Their Therapeutic Potential. In Essential Oil Research: Trends in Biosynthesis, Analytics, Industrial Applications and Biotechnological Production, Malik, S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers, M.R.; Weathers, P.J. Artemisinin permeability via Caco-2 cells increases after simulated digestion of Artemisia annua leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 210, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, N.F.; Kiani, B.H.; Desrosiers, M.R.; Towler, M.J.; Weathers, P.J. Artemisia extracts differ from artemisinin effects on human hepatic CYP450s 2B6 and 3A4 in vitro. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 298, 115587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, P.J.; Elfawal, M.A.; Towler, M.J.; Acquaah-Mensah, G.K.; Rich, S.M. Pharmacokinetics of artemisinin delivered by oral consumption of Artemisia annua dried leaves in healthy vs. Plasmodium chabaudi-infected mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, P.J.; Towler, M.; Hassanali, A.; Lutgen, P.; Engeu, P.O. Dried-leaf Artemisia annua: A practical malaria therapeutic for developing countries? World journal of pharmacology 2014, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Day 0 (µg/mL) | Day 4 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

|

A. annua tea ART dART |

141.2 14.5 |

12.0 5.1 |

| ART ART dART |

141.2 0 |

0.42 0.5 |

| AS AS dART |

192.2 0 |

ND 1.5 |

| DHA DHA dART |

142.2 0 |

ND 6.9 |

| Gene name | Protein encoded |

Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTA2 | α-SMA | ACTGCCTTGGTGTGTGACAA | |

| CACCATCACCCCCTGATGTC | |||

| COL1A1 | Collagen 1 (α1) | GTCAGGCTGGTGTGATGGG | |

| GCCTTGTTCACCTCTCTCGC | |||

| COL3A1 | Collagen III (α1) | GGACACAGAGGCTTCGATGG | |

| CTCGAGCACCGTCATTACCC | |||

| MMP1 | Matrix metalloproteinase 1 | GCATATCGATGCTGCTCTTTC | |

| GATAACCTGGATCCATAGATCGTT | |||

| MMP3 | Matrix metalloproteinase 3 | ACCTGACTCGGTTCCGCCTG | |

| GTCAGGGGGAGGTCCATAGAGGG | |||

| TGFB1 | TGF-β1 | CATTGGTGATGAAATCCTGGT | |

| TGACACTCACCACATTGTTTTTC | |||

| TGFB2 | TGF-β2 | GAGCGACGAAGAGTACTACG | |

| TTGTAACAACTGGGCAGACA | |||

| TGFBR1 | TGF-βR1 | GCAGACTTAGGACTGGCAGTAAG | |

| AGAACTTCAGGGGCCATGT | |||

| GAPDH | GAPDH | GAGTCCACTGGCGTCTTCAC | |

| TTCACACCCATGACGAACAT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).