1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Certain geomaterials (or geologically derived materials) including clay minerals have long been known to possess the ability to improve human health. As the African population continues to suffer various forms of health problems such as environmentally induced diseases resulting from the release of harmful substances into the environment, research has continued to show the strong potential of certain geomaterials in providing remedies and management of these conditions. The present study aims at synthesysing current knowledge of the application of geomaterials, including clay minerals, in the improvement of human health in Africa, charts the developmental pathways of such applications during the past 10 years, and proffer directions along which future research on this important subject should be predicated.

1.2. Methodology

Employing an iterative approach, a comprehensive internet search using Google Search Engine, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink was conducted. Initial searches used broad terms such as ‘geological materials’, ‘clay minerals’ and ‘health benefit’. The articles returned from these indexed databases, and used for this review, were those recognised as credible indexing protocols in terms of appositeness of citations and of assuring that the articles turned out were from trusted sources. The authors further set other inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen for relevant articles, each of which was independently reviewed to determine eligibility for extraction of the requisite review information. An important inclusion criterion was the recency of the articles considered, with respect to the theme of the Conference Session: “Recent Advances in Medical Geology Research in Africa: A decadal view”. Preference was given to articles published during the last 10 years (2015 - 2024), with the inclusion of older articles, only if they are “foundational papers”, “classic papers” or “seminal works” that define the subject of “Medical Geology”.

1.3. Contributions Made

A summary of the relevance of geological materials in providing a range of healing and soothing effects to human diseases and ailments in Africa is presented. An up-to-date synthesis (citations mostly post-dating the year 2015) of research on the oral and topical applications of geomaterials including clay minerals in correcting a variety of maladies in Africans is provided. Furthermore, reasons are proffered as to why the use of certain clay minerals in correcting diseases such as inflammations and their potential in biomedical research is fast becoming a centre of focus among researchers in the field. Applications of geomaterials in treatment of disease by bathing in the thermal mineral waters (balneotherapy) are also critically reviewed.

2.0. Medicinal Clays and Cosmetic Products

Clay minerals are a group of hydrous silicates of aluminium, having a layer (sheetlike) structure, very small particle size and sometimes containing variable amounts of iron, magnesium, alkali metals, alkaline earths, and other cations. Due to their natural abundance and several unique biophysicochemical properties including low toxicity, chemical inertness, favourable rheological characteristics, large specific surface area, swelling behaviour and relatively low cost, clay minerals such as bentonite and kaolinite, are used in a wide range of applications, such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, ceramics, construction materials and environmental remediation.

In Africa, the medicinal uses (as active ingredients or excipients in therapeutical and pharmacological formulations) and cosmetic uses (beauty therapy) of various clays are particularly notable and have been reported in several countries across the Continent. According to Matike et al. (2010), the age-old use of clays in Africa for cosmetic purposes are for: protecting the skin against ultraviolet radiation, skin lightening, cleansing the skin, hiding of skin imperfections and accentuating the beauty of specific parts of the body.

Recent appraisals of the medicinal and cosmetic uses of African clays include the works of Masango et al., 2017; Gomes, 2018; Williams, 2019; Incledion et al., 2021; Morekhure-Mphahlele et al., 2017 and Buthelezi-Dube et al., 2022 and Kgabi and Ambushe, 2023.

Further research is needed to distinguish between ‘healing clays’ and those identified as antibacterial clays, for, as Williams and Haydel noted in 2010: “… the highly adsorptive properties of many clays may contribute to healing a variety of ailments, although they are not antibacterial.” See also: Moosavi, 2017; Nomicisio et al., 2023. According to Cao (2022): “Functionalization of fibrous clays and their organic modified derivatives for high value-added dermopharmaceutical and cosmetic applications is currently an active area of research.”

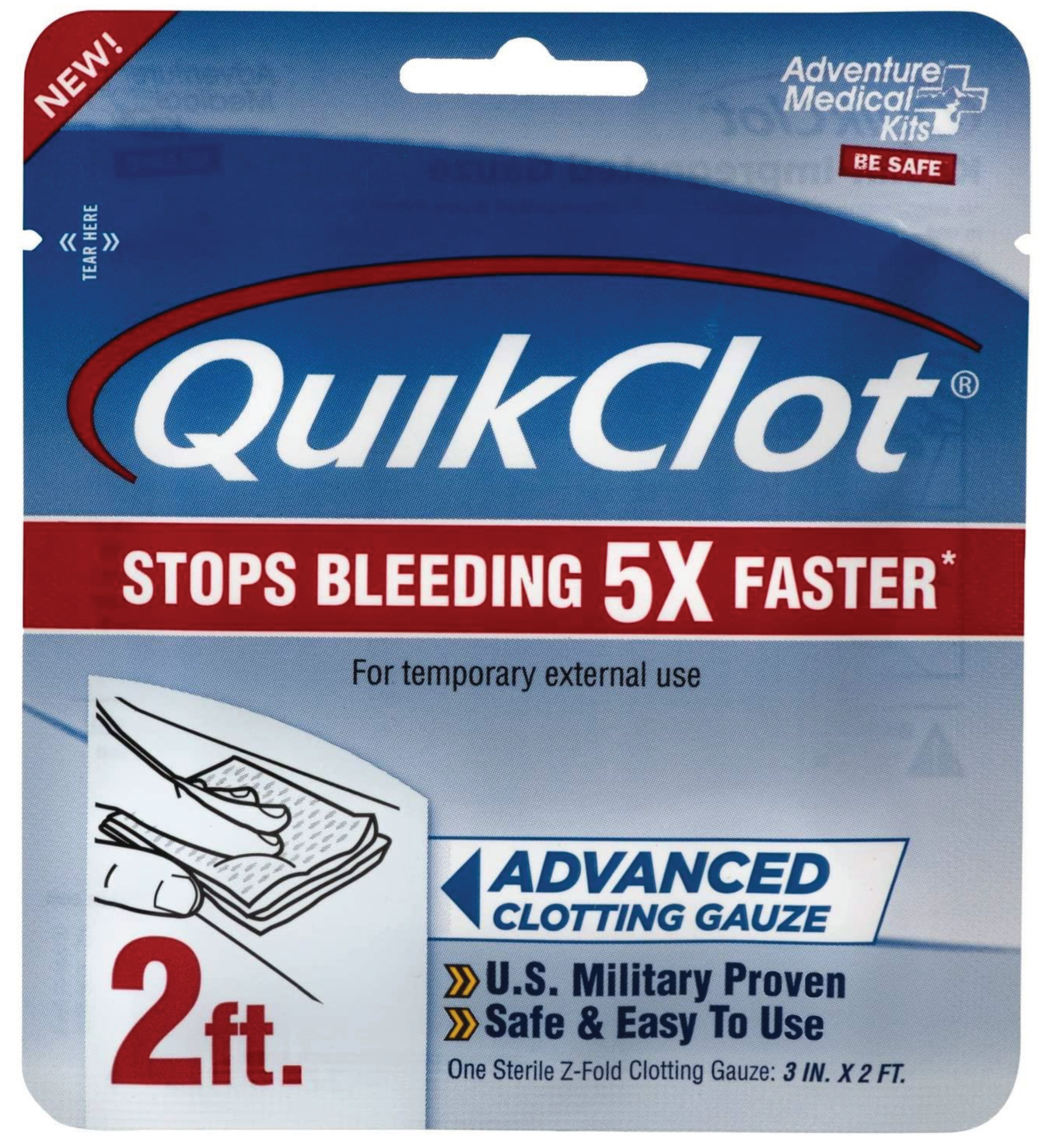

2.1. Zeolite and the Development of QuikClot Formulation

Zeolites are a group of microporous, hydrated, crystalline aluminosilicate minerals that contain alkali and alkaline-earth metals. They have properties similar to those of clays; and, like clays, they have a range of applications in health and medicine. The porous structure of zeolites allows for positive water absorption, increasing the concentration of local platelets and clotting factors

QuikClot is a haemostatic agent which is made from an engineered form of the mineral zeolite. It can rapidly stop bleeding from exposed wounds by absorbing water and concentrating coagulation factors. The engineered zeolite material contains cations that serve as cofactors that activate the clotting of proteins. The first-generation product with an original formulation that contained the active ingredient zeolite, promoted blood clotting. Zeolites not only tend to enter capillaries (resulting in thrombosis) but also tend to absorb water and release excessive heat (See: Guo et al., 2023).

In order to obviate these unwanted side effects (thrombosis and induction of secondary degree burns) when applied

in vivo some modification was made to the original formulation; impregnating it with the mineral kaolinite, to form the second-generation product known as

QuikClot ACS (Advanced Clotting Sponge), which serves to accelerate the body’s natural clotting ability without producing any exothermic reaction (

Figure 1; See Gan et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2021). The QuikClot ACS is reported to be more effective than QuikClot, especially when applied to irregular injury sites without being freely distributed into the wound. This modified product is also easier to remove.

Kaolinite can also be used to stop bleeding and for a condition that involves swelling and sores inside the mouth (oral mucositis) (See, e.g., Alterio et al, 2007); but these applications need confirmation from scientific investigations. Reports also exist on the use of kaolinite to treat diarrhoea and many other conditions (Awad et al., 2017), but there is a dearth of good scientific evidence to support most of these uses. In 2018, Pérez-Gaxiola et al. (2018) noted that smectite was still widely applied for the treatment of acute infectious diarrhoea in children due to its apparent safety and efficacy; and Derakhshankhah et al. (2020) appraised gastro-beneficial effects of oral application of zeolites on patients suffering from illnesses such as diarrhoea.

Mumtaz et al. (2023) looked at safety and efficacy of a kaolin-impregnated haemostatic gauze in cardiac surgery. Du et al. (2023) provide an overview of the currently used haemostatic strategies and materials, including the nanomaterials, zeolite and kaolinite.

Radiation scientists are already using zeolites in low-level nuclear radiation clean-ups. Zeolites are now also being tried on humans to neutralise the effects of nuclear radiation exposure (Finkelman, 2006) and cancer (Pavelić et al., 2001). The CORDIS Project of the European Union Community Horizon 2020 Initiative (Nanoporous and Nanostructured Materials for Medical Applications) is currently researching on application of a prototype material (enterosorbent such as zeolite), that is capable of removing the radioisotopes, toxins and radical species found in the human body after exposure to radiation [CORDIS, EU (2023)]. Du et al. (2023) provide an overview of the currently used haemostatic strategies and materials including the nanomaterials, zeolite and kaolinite.

Pavelić et al. (2018) reviewed safety considerations in in vitro application of the naturally occurring zeolite material, clinoptilolite, and its positive medical effects related to detoxification, immune response, and the general health status of humans.

Data on application of haemostatic agents in Africa is scanty, despite the frequency of armed conflicts in the Region. In 2019, Hafeji wrote in her M.Sc. thesis submitted to the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa that “ … Current available haemostatic gauzes and bandages in South Africa have to be imported and are thus expensive. The purpose of this study was to prepare and evaluate a haemostatic gauze impregnated with chitosan and tannic acid as two effective and cheap haemostatic agents.”

2.2. Use of Titanium Dioxide and Zinc Oxide in Sun Protection Products

Titanium dioxide (rutile; TiO2) and zinc oxide (zincite; ZnO) are minerals that are frequently employed in sunscreens as inorganic physical sun blockers. Sunscreens are used to provide protection against adverse effects of ultraviolet UVB (290 - 320 nm) and UVA (320 - 400 nm) radiation. As TiO2 is more effective in UVB and ZnO in the UVA range, the combination of these particles assures a broad-band UV protection. However, results from some studies indicate significant penetration of the skin barrier by these materials, leading to toxic side effects in skin cells (Smijs and Pavel, 2011). To solve the cosmetic drawback of these opaque sunscreens, manufacturers often use TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) (<100 nm) to replace microsized TiO2 and ZnO (Wang, 2023). The nano-sized versions are also held to reduce white cast and increase sun protection factor (SPF). Although they are reported to be less toxic, more research is needed to fully understand the extent to which nanoparticles may harm cells and organs if they are introduced into our bodies (See: Liang et al., 2022; Xuan et al., 2023).

In addition to its use in sunsreens, topical ZnO preparations occur as calamine or zinc pyrithione, which has been in use as photo-protecting, soothing agents or as an active ingredient in antidandruff shampoos (Gupta et al., 2014). Its use has also expanded considerably over the years for the treatment of several other dermatological conditions including infections (warts, leishmaniasis), inflammatory dermatoses (acne vulgaris, rosacea), pigmentary disorders (melasma), neoplasias (basal cell carcinoma) and others (Gupta et al., 2014).

3.0. Balneotherapy

The term balneotherapy is used to describe a decades-old physical therapy that involves bathing in hot mineral water (hot springs, thermal waters), peloids or gases for health promotion and prevention or treatment of certain diseases. Medicinal mineral resources with considerable potential for development in Africa are: spas, muds and peat deposits.

Balneotherapy is practised in several African countries, particularly those countries with ancient volcanic history, e.g., South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Egypt. This treatment regime has shown significant effects for some diseases such as cardiovascular conditions and skin lesions (Gebretsadik et al., 2021; Gebretsadik, 2023). Recent pertinent references on the role of balneotherapy in the treatment regimen of a host of non-communicable diseases in Africa include those of: Pedrazzini et al., 2016; Sekome and Maddocks, 2019; Williams, 2019; Mangwane and Ntanjana, 2020; Ncube et al., 2020; Oluwaseun et al., 2020; Fikri-Benbrahim et al., 2021; Gebretsadik et al., 2021; Haji et al., 2021; Kgabi and Ambushe, 2023; Wang et al., 2023a).

3.1. Hot Springs and Mineral Waters

The curative properties of geothermal (hot) waters are highly valued in several African countries, especially those countries located around the African Rift Valley, such as Kenya and Ethiopia. This is so, because in Africa, as in many other parts of the world, there is a widely held belief that geothermal waters offer a highly effective treatment for a range of diseases. Despite the abundance of natural hot springs in Africa, however, their acclaimed therapeutic value has still not been thoroughly studied (See, e.g., Gebretsadik, 2023).

Mineral water comes from natural groundwater reservoirs and mineral springs, giving it a much higher ‘mineral’ content than tap water - minerals such as salts of magnesium, calcium, bicarbonate, sodium, sulphate, chloride and fluoride, as well as other naturally occurring chemical constituents are present in varying amounts (Ferreira-Pêgo et al., 2016; Quattrini et al., 2017). The types and amounts of minerals and other chemical constituents in ‘highly mineralised waters’, so also their health benefits, vary greatly and depend on the location from which the water comes.

Back in 2011, Olivier et al. looked at thermal and chemical features of 8 thermal springs located in the northern part of the Limpopo Province, South Africa; and found marked degree of nonconformity with domestic water quality guidelines, with unacceptably high levels for a number of fugitive constituents such as bromide ions, fluoride, mercury, selenium and arsenic. In 2021, Fikri-Benbrahim studied the distribution of thermal springs in Morocco, the classification of their waters, and their health effects, with the aim of valorising and enhancing their effect. Olowoyo et al. (2022) measured the concentrations of trace metals and the physicochemical properties of bottled water purchased in Pretoria, South Africa; and found levels of the hydrogen ions as well as the toxic trace metals: lead, nickel and chromium well above the WHO recommended safe level for human consumption. Angnunavuri et al., (2022) measured the levels of various biophysicochemical properties in plastic packaged water in Ghana, and found the presence of phthalates and pathogenic bacteria in the samples, at-risk levels that require mitigation.

Some have expressed health concerns regarding the use of bottled mineral waters (due to plasticizers and endocrine disruptors); but much of the research in this area has been devoted to their properties and their role in amelioration of different physiological and pathological conditions (e.g., Quattrini et al., 2017; Sunardi et al., 2022; Dobosy et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2023; Pop et al., 2023). There is room for more research in this area.

Kekes et al. (2023) appraise some of the most commonly applied drinking water treatment methods and introduce some novel treatment methods.

3.2. Peloids

Peloids are natural substances (mud or clays) that are admixtures of inorganic and organic substances in different proportions; and used therapeutically as part of balneotherapy, or therapeutic bathing. The most popular peloids are peat pulps, various medicinal clays, mined in various locations in Africa and around the world, and a variety of plant substances. Clinical evidence based on epidemiological studies emphasises the benefits of pelotherapy on degenerative and inflammatory rheumatism taking advantage of the peloid’s analgesic, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and anti-microbial properties (e.g., Cheleschi et al., 2022; Gálvez et al., 2023). There is also evidence of positive effects of peloids on dermatological infections, especially psoriasis; and on skin care functions (cleansing, degreasing, exfoliation, hydrating, tonifying, and reaffirming).

3.3. Spas and Mud Baths

The word spa is used as a Latin abbreviation for S = salud, P = per, A = aqua, or “Health through the water”. A spa is an indoor location where mineral-rich spring water (and sometimes well water or seawater) is used to give medicinal baths. The water, with certain mineral constituents and often warm, gives the spa meaning from a religious, mythical, symbolic and/or from many other perspectives (See: Lund, 2001).

Mud baths (

Figure 2) have been in use since ancient times and can be found in many upmarket spas around the world. The unique and complex chemical composition of mud enables it to improve the activity of glutathione enzyme and superoxide dismutase in skin, which helps the skin anti-aging (Tiang et al., 2022).

Mud baths are used by the application of warm (typically foul-smelling) sulphur containing mud as a cure for various skin ailments (Fraioli et al., 2018). Mud is also reported to have a role in the treatment osteoarthritis, especially knee osteoarthritis and can also increase the chemotaxis of macrophages (See: Tiang et al., 2022).

3.4. Peat Preparations

The definition of peat is variable, although most authors agree that it is a brown (organic rich) material consisting primarily of decayed and partially decayed plant remains that have accumulated on acidic, boggy ground over a long period of time (See, e.g., Laurenco et al., 2022).

Peat and various peat preparations have been successfully used in balneology, with the most common applications being peat mud, suspension baths and poultices. As a natural source of humic substances, peat preparations are of great potential interest in dermatology and cosmetology (See, e.g., Wollina, 2009); and many peat preparations are now available and applied in humans as well as in veterinary medicine. According to Wollina (2009), peat applied outside of the body may induce systemic effects by absorbing humic substances. Water-soluble compounds of fulvic and ulmic acids stimulate a response on the contractile activity of smooth muscle by dopaminergic D2 and α2-adrenergic stimulation.

The literature is awash with accounts of the traditional uses of medicinal plants of Africa (e.g., Popoola et al., 2022; Gang et al., 2023; Ndhlovu et al., 2023); but despite the abundance of peatlands on the Continent (See: Box 1) there is a paucity of reports on the application of peat therapy.

Box 1.

Africa’s peatlands.

Box 1.

Africa’s peatlands.

Peatlands cover nearly 40 million hectares across Africa, including some of the world’s most important peatlands, home to unique and rare flora and fauna. The largest African peatland area lies in the Congo Basin and stores around 30 billion tonnes of carbon, while the peatland area in the Nile Basin stores another 10 billion tonnes. The Cuvette Centrale peatland complex lies in the heart of the Congo Basin Forest, and is the second largest tropical forest after the Amazon. It covers an area of 16.7 million hectares, and is one of the largest contiguous peatland complexes in the world. The Cuvette Centrale accounts for more than a third of the world’s tropical peatlands and a major carbon store, accounting for more than a quarter of the carbon stored in such areas. This makes it very essential for mitigating climate crisis.

Paraphrased from: HBF, 2023.

|

3.5. Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a worldwide chronic, debilitating skin disorder in which the immune system becomes overactive, causing skin cells to multiply very rapidly (NIAMS, 2023). The skin cells build up and form inflamed, red raised areas that often develop into silvery scales and itchy, dry patches most often on the scalp, elbows, or knees. This condition is probably widespread in Africa as it is in the rest of the world; but it is thought to be widely under-reported (See, e.g., El-Komy et al., 2020). Scientists do not yet fully understand what causes psoriasis, but they know that it involves a mix of genetics and environmental factors (Branisteanu et al., 2022). Many of the studies that have been done to unravel the cause(s) have considered that deficiency of the nutrient element, magnesium, and a possible climatic factor (e.g., cold weather) may be related cofactors.

Climatotherapy is a well-described treatment regime for psoriasis (See

Section 3.5.2, this article).

3.5.1. Psoriasis Management

Bathing in spas containing mineral salts such as magnesium chloride (MgCl2) has been considered an important treatment modality. Repeated bathing in the Dead Sea (a hypertonic salt solution) for a certain length of time has a therapeutic effect on psoriasis and other skin diseases (Emmanuel et al., 2020; Jacobs and Kgokolo, 2020; Dai et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023b).

In Africa, there is a wide variety of available treatment options, ranging from: topical treatment, e.g., application of steroid creams or ointments such as topical corticosteroids, commonly used to treat mild to moderate psoriasis in most areas of the body (Haigh and Smith, 2002; Abdulghani et al., 2011). Phototherapy, i.e., treatment exclusively using light, is applied for moderate disease, whereas systemic therapy or biological agents are applied for more advanced form of the disease (WCD, 2023). However, there still remains an unmet need for clinical guidelines on managing patients with plaque psoriasis in Africa (Steinhoff et al., 2020).

3.5.2. Dead Sea Benefits for Psoriasis

The unique chemical composition of the Dead Sea (27% of various salts as compared to 3% in normal seawater), as well as its other outstanding characteristics, has made it an important centre for health research; in particular, investigations concerning the aetiology and treatment of psoriasis (

Figure 3).

As indicated in

Section 3.5.1, bathing in spas containing mineral salts such as MgCl

2 has been considered an important treatment modality. Many studies have concluded that repeated bathing in the Dead Sea (a hypertonic salt solution) for a certain length of time is found to have a therapeutic effect on psoriasis,

inter alia (e.g., Emmanuel et al., 2020; Jacobs and Kgokolo, 2020; Wang et al., 2023b). The high content of mineral salts has been shown to have a distinctly positive effect on the body, boosting cell metabolism, enhancing the body’s capacity for absorbing nourishment, and getting rid of toxins (See e.g., earlier work by Proksch et al., 2005). Additionally, the high salt content benefits the skin by promoting elasticity and smoothing the appearance of lines and wrinkles (Dai et al., 2023). The mud from the bottom of the Dead Sea is also very rich in ‘minerals’, including magnesium, calcium, sodium, zinc, potassium, and sulphur. People smear it over their bodies before they enter the water (Dai et al., 2023). Thus, many dermatologists have carefully looked at the salt content,

re.: MgCl

2 in the waters of Dead Sea spas and the effect it has on psoriasis in a bid to identify suitable management regimens for psoriasis.

Climatotherapy, or climate therapy, is one of the oldest forms of medical tourism (Bugyi, 1963; Vovk et al., 2020; Rogerson and Rogerson, 2021; Droli et al., 2022) and involves travel to what is believed to be a more beneficial climate. The Dead Sea has a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh), with year-round sunny skies and dry air - just what the doctors treating psoriasis would order. Dead Sea climatotherapy (DSC) in Israel consists of intensive sun and Dead Sea bathing and has been found to be very effective in improving clinical and patient-reported outcomes (Emmanuel et al., 2022).

3.53. The Future of Balneotherapy

Although balneotherapy (BT) is now a well-established non-pharmacologic complementary therapy for different rheumatic diseases (probably due to combination of mechanical, thermal, and chemical effects), the exact mechanism of its action is not yet fully understood (Cheleschi et al. (2022). Well designed, controlled, clinical trials are required for various arthritic and rheumatic diseases, as well as other conditions which are treated in spas (Bender et al., 2005). However, circumventing the difficulties in conducting such studies, especially making them double-blind and obtaining appropriate placebo controls, still remains a problem. The long-term effects of balneotherapy look good and seem justified on a cost-benefit basis. The physiological effects of the various therapeutic modalities used in spas require further study. However, financial support for such studies and the necessary therapeutic trials remains a problem.

4. Amulets and Talismans

In cultural studies, the terms amulets and talismans have been defined in various ways; but, perceived as earth materials, the usage of Probert and Sijpesteijn in their 2022 book is perhaps the most customised, viz.: “…amulets and talismans comprise material objects that have been manufactured and used within the Muslim world for protection, healing and to procure good fortune.” Thus, the use of amulets and talismans is generally viewed as embedded in religious, medical and mystical practices, integrated into a behavioural continuum.

Amulets are an important part of the life of some African communities, from birth to death. Their use in the West, however, is completely dissociated from the cultural context and the sacred meaning which is given to these objects in Africa. In the West, there is, instead, a clear distinction between fashionable objects which are used for aesthetic reasons, and amulets, which in African culture continue to be considered sacred objects.

Amulets can be of various compositions. Typical amulets are crystals that are usually worn or carried for defence and protection. Only minerals with distinctive crystallographic characteristics are effective for amulets. Those worn externally by the Tuareg (a traditionally feudal society inhabiting the Sahara) can be in the form of necklaces, finger rings, fastened on a man’s turban (Tagelmusut) or used as decoration in the pigtail braids in the headdress of girls and women. These pieces may be silver crosses, semiprecious stones, silver or bone rings with numbers or letters inscribed on them.

According to Sotkiewicz (2014), talismans play a vital role in the protection against supernatural powers and have preventive functions against diseases; and as Hureiki (2014) points out: “Amulets and talismans are the most popular and most frequented defensive instrument among the Tuareg.”

A talisman is an object, often a crystal or gem stone, that has a specific ability to aid a person in focusing and amplifying his or her power. All through history, curative, protective, and divination powers have been attributed to crystal talismans such as rubies, sapphires, emeralds, and virtually every other precious stone.

5. Metallic Implants and Prostheses

Medical implants are devices or tissues that are placed inside or on the surface of the body. Many implants are prosthetics, intended to replace missing body parts. Metallic implant materials have gained immense clinical importance in the medical field for a long time.

The reason metals and alloys such as aluminium (Al), titanium (Ti), stainless steel and cobalt-chromium (Co-Cr) alloy have been found to be so suitable for the construction of implants and prostheses is because of their biocompatibility and high mechanical strength (Kulkarni et al., 2022; Meng et al., 2023; Saha and Roy).

The use of surgical implants and prosthetic devices to replace the original function of different components of the human biological system is now a well-established tradition in the history of medicine. However, these new technologies need to be further researched to gauge the full extent to which they can enable human beings not just to survive, but to thrive in the face of any conceivable physical difficulty.

6.0. Conclusion

The occurrence and mining of geological materials continue to contribute significantly to Africa’s economic growth and development of its infrastructure. However, mining of geological materials has also been a major cause of, at times, life-threatening diseases such as cancer, lung diseases and severe dermatological infections, among others.

Nonetheless, there is an important aspect to the impact of deployment of geological materials on human health and well-being. Africa is endowed with several therapeutic geological materials that could help as medical resources for the treatment of many diseases some of which are life-threatening. Various illnesses and maladies have been treated with Earth materials such as malachite and clays for infections, clays and pearls for gastrointestinal problems, and amber for alcoholism and for strengthening of the immune system.

The use of zinc oxide for dermatological conditions, zeolite and kaolin to promote clotting, natural zeolite, clinoptilolite as a new adjuvant in anticancer therapy, among others, underscores the positive impact that geological materials and clay minerals have on humans.

Haemostatic agents can play a key role in the emergency control of haemorrhage following various types of trauma, and will decrease the associated mortality and morbidity. However, there is still the need for the continued refinement of the composition and formation of such dressings. In addition, current haemostats are mostly only available for use in developed countries. More effort should be made to ensure that these life-saving materials in both combat situations and events occurring in everyday life, be made available to-, or produced in, developing parts of the world.

The use of nanoparticles in cosmetics has great potential, but it poses a regulatory challenge, because their properties may vary widely, depending on their size, shape, surface area and coatings. Improved haemostatic materials show great potential for clinical use, but few have been translated from laboratory studies to clinical applications. In-depth research into clinical trials using these resources has the potential of opening up innovative ways for the cure of several diseases some of which could result in high human mortality rates.

Thermal mineral waters, mud baths and peat baths have been used for various therapeutic purposes including beautification, nourishing the body, relief of stress, joint pain, rheumatoid arthritis and certain skin ailments. The therapeutic value of bathing in hot waters with mineral salts has been recognised since the 1800s for a variety of conditions, especially skin conditions like psoriasis. Numerous studies have attempted to define the risk factors for developing psoriasis, a disease with a hitherto unknown aetiology. To obviate bias and ensure that a temporal relationship is established, population-based case-control studies of patients with incident (newly developed) psoriasis needs to be designed to be able to identify potential risk factors for developing this disease.

Bottled water is often considered to be generally safe and sterile; but, the risk for health should not be minimised, given that toxins, bacteria, fungus and other microbiological pollutants may survive in bottled water and can result in different diseases in humans, most frequently gastroenteritis. Doctors should advise patients to check the mineral content of their drinking water, whether tap or bottled, and choose water that is most appropriate for their needs.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval is not applicable. All authors consented to participate in writing the manuscript.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish the manuscript.

Availability of data and material

The datasets analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Hyperlinks to documents from which secondary data were obtained are provided in the ‘Reference List’.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competition of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Authors’ contributions

OOO, OOF and TCD wrote the first draft of the manuscript while GDA, RMC, KKN made editorial contributions and were contributors in the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgment

Any copyrighted materials on these pages are used under “fair use” for the purpose of study and review. All illustrations and citations are credited to their appropriate and respective sources. The authors are particularly grateful to the institutions and colleagues who have permitted their images and photographs to be used in this document; all copyright is retained by them and their institutions. Any required acknowledgement omitted is unintentional.

References

- Abdulghani et al., 2011. Management of Psoriasis in Africa and the Middle East: a Review of Current Opinion, Practice and Opportunities for Improvement. The Journal of International Medical Research 39, 1573 - 1588 1573. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/147323001103900501 (accessed 02.01.2024). [CrossRef]

- Alterio, D., Jereczek-Fossa, B. A., Fiore, M. R., Piperno, G., Ansarin, M. and Orecchia, R., 2007. Cancer treatment-induced oral mucositis. Anticancer Research 27 (2), 1105 - 1125. https://air.unimi.it/retrieve/handle/2434/38027/1546183/1105.full.pdf (accessed 26.12.2023).

- Angnunavuri, P.N., Attiogbe, F., Dansie, A. and Mensah, B., 2022. Evaluation of plastic packaged water quality using health risk indices: A case study of sachet and bottled water in Accra, Ghana. The Science of the Total Environment 832, 155073. (accessed 31.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.E., López-Galindo, A., Setti, M., El-Rahmany, M. M. and Iborra, C.V., 2017. Kaolinite in pharmaceutics and biomedicine. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 533 (1), 34 - 48. (accessed 26.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Bender, T., Karagülle, Z., Bálint, G. P., Gutenbrunner, C., Bálint, P. V. and Sukenik, S., 2005. Hydrotherapy, balneotherapy, and spa treatment in pain management. Rheumatology International 25 (3), 220 - 224. (accessed 06.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Branisteanu, D.E., Cojocaru, C., Diaconu, R., Porumb, E.A., Alexa, A.I., Nicolescu, A.C., Brihan, I., Bogdanici, C.M., Branisteanu, G., Dimitriu, A., Zemba, M., Anton, N., Toader, M. P., Grechin, A. and Branisteanu, D.C., 2022. Update on the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis (Review). Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 23 (3), 201. (accessed 31.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Bugyi, B. 1963: Data on medical tourism and climate therapy in the High Tatra mountains. Orvosi Hetilap 104: 1426-1428. In Hungarian.

- Buthelezi-Dube, N.N., Muchaonyerwa, P., Hughes, J., Modi, A. and Caister, K., 2022. Properties and indigenous knowledge of soil materials used for consumption, healing and cosmetics in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Soil Science Annual 73 (4), 157408. (accessed 14.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Cao, L., Xie, W., Cui, H., Xiong, Z., Tang, Y., Zhang, X. and Feng, Y., 2022. Fibrous clays in dermopharmaceutical and Cosmetic applications: Traditional and Emerging Perspectives.

- International Journal of Pharmaceutics 625, 122097. (accessed 14.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Cheleschi, S., Tenti, S., Seccafico, I., Gálvez, I., Fioravanti, A. and Ortega, E., 2022. Balneotherapy year in review 2021: Focus on the mechanisms of action of balneotherapy in rheumatic diseases. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 29 (6), 8054 - 8073. (accessed 06.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- CORDIS (European Union), 2023. Treating the long-term effects of acute radiation syndrome. Horizon 20 Project on: Nanoporous and Nanostructured Materials for Medical Applications. https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/443001-treating-the-long-term-effects-of-acute-radiation-syndrome (accessed 26.12.2023).

- Dai, D., Ma, X., Yan, X. and Bao, X., 2023. The biological role of Dead Sea Water in skin health: A review. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 21. (accessed 01.12.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Derakhshankhah, H., Jafari, S., Sarvari, S., Barzegari, E., Moakedi, F., Ghorbani, M., Varnamkhasti, B.S., Jaymand, M., Izadi, Z. and Tayebi, L., 2020. Biomedical applications of zeolitic nanoparticles, with an emphasis on medical interventions. International Journal of Nanomedicine. (accessed 26.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Dobosy, P., Illés, Á., Endrédi, A. and Záray, G., 2023. Lithium concentration in tap water, bottled mineral water, and Danube River water in Hungary. Scientific Reports 13, 12543. (accessed 31.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Droli, M., Bašan, L. and Vassallo, F.G., 2022. Positioning climate therapy stays as a health tourism product: An evidence-based approach. Emerging Science Journal 6 (2), 256. (ISSN: 2610-9182). [CrossRef]

- Du., J., Wang, J., Xu, T., Yao, H., Yu, L. and Huang, D., 2023. Hemostasis strategies and recent advances in nanomaterials for hemostasis. Molecules. 2023 28 (13), 5264. [CrossRef]

- El-Komy, M.H.M., Mashaly, H., Sayed, K.S., Hafez, V., El-Mesidy, M.S., Said, E.R., Amer, M.A., AlOrbani, A.M., Saadi, D.G., El-Kalioby, M., Eid, R.O., Azzazi, Y., El Sayed, H., Samir, N., Salem, M.R., El Desouky, E.D., Zaher, H.A.E. and Rasheed, H., 2020. Clinical and epidemiologic features of psoriasis patients in an Egyptian Medical Center. JAAD International 1 (2), 81- 90. (accessed 02.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, T., Lybæk, D., Johansen, C. and Iversen, L., 2020. Effect of Dead Sea climatotherapy on psoriasis: A prospective cohort study. Frontiers in Medicine 7, 83. (accessed 05.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, T., Petersen, A., Houborg, H. I., Rønsholdt, A. B., Lybaek, D., Steiniche, T., Bregnhøj, A., Iversen, L. and Johansen, C., 2022. Climatotherapy at the Dead Sea for psoriasis is a highly effective anti-inflammatory treatment in the short term: An immunohistochemical study. Experimental Dermatology 31 (8), 1136 - 1144. (accessed 05.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Pêgo, C., Babio, N., Eyzaguirre, F.M., Miñana, I.V., Salas-Salvadó, J., 2016. Water mineralization and its importance for health. Alimentacion, Nutricion y Salud 23, 4 - 18.

- https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Cintia-Ferreira-Pego/publication/304771767_Water_mineralization_and_its_importance_for_health/links/577a1b9008aeb9427e2cabb7/Water-mineralization-and-its-importance-for-health.pdf (accessed 31.12.2023).

- Fikri-Benbrahim, K., Houti, A.; El Ouali Lahami, A., Flouchi, R., El Hachlafi, N., Houti, M. and Rachiq, S., 2021. Main therapeutic uses of some Moroccan hot springs’ waters. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2021, Article ID 5599269, 11 pp. (accessed 31.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Finkelman R.B., 2006. Health benefits of geologic materials and geologic processes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 3 (4), 338 - 342. (accessed 05.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Fraioli, A., Mennuni, G., Fontana, M., Nocchi, S., Ceccarelli, F., Perricone, C., Serio, A., 2018. Efficacy of spa therapy, mud-pack therapy, balneotherapy, and mud-bath therapy in the management of knee osteoarthritis. A systematic review. BioMed Research International 2018, 1 - 9. (accessed 30.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, I., Hinchado, M.D., Otero, E., Navarro, M.C., Ortega-Collazos, E., Martín-Cordero, L., Torres-Piles, S.T. and Ortega, E., 2023. Circulating serotonin and dopamine concentrations in osteoarthritis patients: A pilot study on the effect of pelotherapy. International Journal of Biometeorology, 2023. (accessed 27.12.2023). [CrossRef]

- Gan, C., Hu, H., Meng, Z., Zhu, X., Gu, R., Wu, Z., Wang, H., Wang, D., Gan, H., Wang, J., Dou, G., 2019. Characterization and Hemostatic Potential of Two Kaolins from Southern.

- China. Molecules 24, 3160. (accessed 26.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Gang, R., Matsabisa, M., Okello, D. and Kang, Y., 2023. Ethnomedicine and ethnopharmacology of medicinal plants used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus in Uganda. Applied Biological Chemistry 66, 39 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gebretsadik, A., Taddesse, F., Melaku, N. and Haji, Y., 2021. Balneotherapy for musculoskeletal pain management of hot spring water in southern Ethiopia: Perceived improvements. Inquiry: A Journal of Medical Care Organization, Provision and Financing, 58, 469580211049063. (accessed 08.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Gebretsadik, A., 2023. Effect of balneotherapy on skin lesion at hot springs in southern Ethiopia: A single-arm prospective cohort study. Clinical Cosmetic Investigations in Dermatology 2023 (16) 1259 - 1268. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C. de Sousa F., 2018. Healing and edible clays: a review of basic concepts, benefits and risks. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 40, 1739 - 1765. (accessed 14.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Wang, M., Liu, Q., Liu, G., Wang, S. and Li, J., 2023. Recent advances in the medical applications of hemostatic materials. Theranostics 13 (1), 161 - 196. (accessed 28.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M., Mahajan, V.K., Mehta, K.S., Chauhan, P.S., 2014. Zinc Therapy in Dermatology: A Review. Dermatology Research and Practice 2014. (accessed 26.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Hafeji, A., 2019. Formulation of a topical haemostatic drug delivery system for minor wounds and abrasions. Masters of Science Thesis in Medicine (Pharmacotherapy),.

- Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/45c0edd4-d873-4605-8c6e-45ef34e172a7/content (accessed 27.12.2023).

- Haigh, J.M. and Smith, E.W., 2002. The registration of generic topical corticosteroid formulations in South Africa: A Report. http://hdl.handle.net/10962/d1006068 (accessed 02.01.2024).

- Haji, Y., Taddesse, F., Serka, S. and Gebretsadik, A., 2021. Effect of balneotherapy on chronic low back pain at hot springs in southern Ethiopia: Perceived improvements from pain. Journal of Pain Research 14, 2491 - 2500. [CrossRef]

- HBF (Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and Three Other Institutions), 2023. Peatland Atlas 2023: Facts and Figures About Wet Climate Guardians. Global Peatlands Initiative. https://eu.boell.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/peatlandatlas2023_web_20230914.pdf (accessed 30.12.2023).

- Huang, Y., Tan, Y., Wang, L., Lan, L., Luo, J., Wang, J., Zeng, H. and Shu, W., 2023. Consumption of very low-mineral water may threaten cardiovascular health by increasing homocysteine in children. Frontiers in Nutrition 10, 1133488. (accessed 31.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Hureiki, J., 2004. Tuareg - Heilkunst und spirituelles Gleichgewicht. (In German); 1st Edition. 235 pages. Cargo Verlag (Schwülper / Hülperode). ISBN 978-3-9805836-5-7. https://www.amazon.de/Tuareg-spirituelles-Gleichgewicht-Jacques-Hureiki/dp/3980583651 (accessed 28.12.2023).

- Incledion, A., Boseley, M., Moses, R.L., Moseley, R., Hill, K.E., Thomas, D.W., Adams, R.A., Jones, T.P. and BéruBé, K.A., 2021. A new Look at the purported health benefits of commercial and natural clays. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 58. (accessed 14.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, T. and Kgokolo, M.C.M., 2020. Treatment of psoriasis. SA Pharmaceutical Journal 87 (6). http://hdl.handle.net/2263/82841 (accessed 06.01.2024).

- Kekes, T., Tzia, C. and Kolliopoulos, G., 2023. Drinking and natural mineral water: Treatment and quality-safety assurance. Water 2023, 15, 2325. (accessed 31.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Kgabi, D.P. and Ambushe, A.A., 2023. Characterization of South African bentonite and kaolin clays. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12679. (accessed 08.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.V., Nemade, A. and Sonawwanay, P.D., 2023. An Overview on Metallic and Ceramic Biomaterials. In: Dave, H.K., Dixit, U.S and Nedelcu, D. (Eds.), Recent Advances in Manufacturing Processes and Systems. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. Springer Nature. (accessed 05.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Laurenco, M., Fitchett, J.M. and Woodborne, S., 2022. Peat definitions: A critical review. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 47 (4). (accessed 30.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y. Simaiti, A. Xu, M. Lv, S., Jiang, H., He, X., Fan, Y., Zhu, S., Du, B., Yang, W. et al., 2022. Antagonistic skin toxicity of co-exposure to physical sunscreen ingredients zinc oxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2769. (accessed 26.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.W., 2001. Balneological use of thermal waters. Conference: International Geothermal Days ‘Germany 2001’, Bad Urach, Germany, September 17 - 22, 2001.

- https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/servlets/purl/892119 (accessed 30.12.2023).

- Mangwane, J. and Ntanjana, A., 2020. Wellness Tourism in South Africa: Development Opportunities. In: Rocha, Á., Abreu, A., de Carvalho, J., Liberato, D., González, E., Liberato, P. (Eds) Advances in Tourism, Technology and Smart Systems. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, vol 171. Springer, Singapore. (accessed 08.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Masango, C.A., Ekosse, G.I. and Netshandama, V., 2017. Indigenous knowledge use of clay within an African context: Possible documentation of entire clay properties? Southern African Journal for Folklore Studies 27 (1), 92 - 104. (accessed 14.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Meng, M., Wang, J., Huang, H., Liu, X., Zhang, J. and Li, Z., 2023. 3D printing metal implants in orthopedic surgery: Methods, applications and future prospects. Journal of Orthopaedic Translation 42, 94 - 112. (accessed 06.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Morekhure-Mphahlele, R., Focke, W.W. and Grote, W, 2017. Characterisation of vumba and ubumba clays used for cosmetic purposes. South African Journal of Science 113 (3 - 4), 1- 5. (accessed 14.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, M., 2017. Bentonite clay as a natural remedy: A brief review. Iranian Journal of Public Health 46 (9), 1176 - 1183. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5632318/ (accessed 14.09.2023).

- Mumtaz, M., Thompson, R. B., Moon, M. R., Sultan, I., Reece, T. B., Keeling, W. B. and DeLaRosa, J., 2023. Safety and efficacy of a kaolin-impregnated hemostatic gauze in cardiac surgery: A randomized trial. JTCVS Open (Elsevier) 14, 134 - 144. (accessed 28.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Ncube, S., Mlunguza, N,Y., Dube, S, Ramganesh, S., Ogola, H.J.O., Nindi, M.M., Chimuka, L., Madikizela, L.M., 2020. Physicochemical characterization of the pelotherapeutic and balneotherapeutic clayey soils and natural spring water at Isinuka traditional healing spa in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The Science of the total environment 717, 137284. (accessed 08.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Ndhlovu, P.T., Asong, J.A., Omotayo, A.O., Otang-Mbeng, W. and Aremu, A.O., 2023. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by indigenous knowledge holders to manage healthcare needs in children. PLoS ONE 18 (3): e0282113. (accessed 30.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- NIAMS (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases), 2023. Psoriasis. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/psoriasis (accessed 31.12.2023).

- Nomicisio, C., Ruggeri, M., Bianchi, E., Vigani, B., Valentino, C., Aguzzi, C., Viseras, C., Rossi, S. and Sandri, G., 2023. Natural and synthetic clay minerals in the pharmaceutical and biomedical fields. Pharmaceutics 15 (5), 1368. (accessed 14.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Olivier, J., Venter, J.S. and Jonker, C.Z., 2011. Thermal and chemical characteristics of hot water springs in the northern part of the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Water SA 37 (4), 427 - 436. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1816-79502011000400001&lng=en&tlng=en. (accessed 31.12.2023).

- Olowoyo, J. O., Chiliza, U., Selala, C. and Macheka, L., 2022. Health risk assessment of trace metals in bottled water purchased from various retail stores in Pretoria, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19 (22), 15131. (accessed 31.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Oluwaseun, O.T., Makama, A.Y., Ibrahim, S.Z., Rahman, S.A. and Oladimeji, O., 2020. Balneotherapy/spa therapy: Potential of Nigerian thermal hot spring waters for musculoskeletal disorders and chronic health conditions. International Journal of Advanced Research and Publications 4 (3), 95 - 100. ISSN: 2456-9992. http://www.ijarp.org/published-research-papers/mar2020/Balneotherapyspa-Therapy-Potential-Of-Nigerian-Thermal-Hot-Spring-Waters-For-Musculoskeletal-Disorders-And-Chronic-Health-Conditions.pdf (accessed 08.09.2023).

- Pavelić, K.S., Simović Medica, J., Gumbarević, D., Filošević, A., Pržulj, N. and Pavelić, K., 2018. Critical review on zeolite clinoptilolite safety and medical applications in vivo. Frontiers in Pharmacology 9, 1350. (accessed 08.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Pavelić, K., Hadžija, M., Bedrica, L., Pavelić, J., Ðikić, I., Katić, M., Kralj, M., Bosnar, M.H., Kapitanović, S., Poljak-Blaži, M., Križanac, Š., Stojković, R., Jurin, M., Subotić, B., Čolić, M., 2001. Natural zeolite clinoptilolite: New adjuvant in anticancer therapy. Journal of Molecular Medicine 78, 708 - 720. (accessed 05.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Pedrazzini, A., Delsignore, R., Martelli, A., Tocco, S., Vaienti, E., Ceccarelli, F. and Pogliacomi, F., 2016. Thermal balneotherapy in Antsirabe-Madagascar: Water analysis and its applications in an African context. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis 87, Suppl. 1, 25 - 33.

- Pérez-Gaxiola G., Cuello-García, C.A., Florez, I.D. and Pérez-Pico, V.M., 2018. Smectite for acute infectious diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018; 4 (4):CD011526. [CrossRef]

- Pop, M.S., Cheregi, D.C., Onose, G., Munteanu, C., Popescu, C., Rotariu, M., Turnea, M.-A., Dogaru, G., Ionescu, E.V., Oprea, D.; et al., 2023. Exploring the potential benefits of natural calcium-rich mineral waters for health and wellness: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3126. (accessed 31.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Popoola, T.D., Segun, P.A., Ekuadzi, E. Dickson, R.A., Awotona, O.R., Nahar, L., Sarker, S.D. and Fatokun, A.A., 2022. West African medicinal plants and their constituent compounds as treatments for viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 30, 191–210 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Probert, M.A.G. and Sijpesteijn, P.M., 2022. Introduction. In: Amulets and Talismans of the Middle East and North Africa in Context. Transmission Efficacy and Collections. Volume 13 of Leiden studies in Islam and society, pages 1 - 12. ISSN 2210-8920. (accessed 28.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Proksch, E., Nissen, H.-P., Bremgartner, M., Urquhart, C., 2005. Bathing in a magnesium-rich Dead Sea salt solution improves skin barrier function, enhances skin hydration, and reduces inflammation in atopic dry skin. International Journal of Dermatology 44, 151 - 157. (accessed 28.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Quattrini, S., Pampaloni, B. and Brandi, M.L., 2017. Natural mineral waters: Chemical characteristics and health effects. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism 13 (3), 173 - 180. Epub 2017 Feb 10. [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C.M. and Rogersom, J.M., 2021. Climate therapy and the development of South Africa as a health resort, c.1850 - 1910. Bulletin of Geography Socio-Economic Series 52 (52), 111 - 121. https://apcz.umk.pl/BGSS/article/view/34307/29066 (accessed 06.01.2024).

- Saha, S. and Roy, S., 2023. Metallic dental implants wear mechanisms. Materials and Manufacturing Processes: A Literature Review. Materials 2023 16 (1), 161. (accessed 05.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Sekome, K. and Maddocks, S., 2019. The short-term effects of hydrotherapy on pain and self-perceived functional status in individuals living with osteoarthritis of the knee joint. South African Journal of Physiotherapy 75 (1), a476. (accessed 08.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Smijs, T.G. and Pavel, S., 2011. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness, Nanotechnology, Science and Applications, 4:, 95-112. [CrossRef]

- Sotkiewicz, H. 2014. Amulets and talismans of the central Sahara – Tuareg art in context of magical and mystical beliefs. Art of the Orient 3, 225-246. https://hasp.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/journals/ao/article/view/8801 (accessed 28.12.2023).

- Steinhoff, M., Ammoury, A.F., Ahmed, H.M., Mohamed Fathy Soliman Gamal, H.F.S. and El Sayed, M.H., 2020. The Unmet Need for Clinical Guidelines on the Management of Patients with Plaque Psoriasis in Africa and the Middle East, Psoriasis: Targets and Therapy 10, 23 - 28. [CrossRef]

- Sunardi, D., Chandra, D.N., Medise, B.E., Manikam, N.R.M., Friska, D., Lestari, W. and Insani, P. N.C., 2022. Health effects of alkaline, oxygenated, and demineralized water compared to mineral water among healthy population: a systematic review. Reviews on Environmental Health. (accessed 31.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Tian, X., Zhang, Y., Li, H., Jiao, Y., Wang, Q., Zhang, Y., Ma, N. and Wang, W., 2022. Property of mud and its application in cosmetic and medical fields: A review. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 12, 4235 - 4251. [CrossRef]

- Vovk, V., Beztelesna, L. and Pliashko, O., 2021. Identification of factors for the development of medical tourism in the World. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (21), 11205. (accessed 06.01.2024) . [CrossRef]

- Xuan, L., Ju, Z., Skonieczna, M., Zhou, P. K. and Huang, R., 2023. Nanoparticles-induced potential toxicity on human health: Applications, toxicity mechanisms, and evaluation models. MedComm 4 (4), e327. (accessed 26.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., 2023. The comparison of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide used in sunscreen based on their enhanced absorption. Applied and Computational Engineering 24, 237 - 245. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Li, S., Bai, J., Cai, X., Tang, S., Lin, P., Sun, Q., Qiao, J. and Fang, H., 2023a. Bimekizumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease 14, 20406223231163110. (accessed 08.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.C., Song, Q.C., Chen, C.Y. and Su, T.C., 2023b. Cardiovascular physiological effects of balneotherapy: focused on seasonal differences. Hypertension Research 46, 1650 - 1661 (2023). (accessed 08.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- WCD (World Congress on Dermatology), 2023. Focus on Psoriasis: A Report from the 25th World Congress of Dermatology, Singapore, 2023.

- https://psoriasiscouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2023-WCD-Congress-Report.pdf (accessed 02.01.2024).

- Williams, L.B. and Haydel, S.E., 2010. Evaluation of the medicinal use of clay minerals as antibacterial agents. International Geology Reviews (2010) 52 (7/8), 745 - 770. [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.B., 2019. Natural antibacterial clays: Historical uses and modern advances. Clays Clay Minerals 67, 7 - 24 (2019). (accessed 08.09.2023) . [CrossRef]

- Wollina.U., 2009. Peat: A natural source for dermatocosmetics and dermatotherapeutics. J Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery 2009, 2 (1):17 - 20. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y., Hu, H., Min, N., Wei, Y., Li, X. and Li, X., 2021. Application and outlook of topical hemostatic materials: A narrative review. Annals of Translational Medicine 9 (7), 577. (accessed 26.12.2023) . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).