1. Introduction

Wilson disease (WD), or progressive hepatolenticular degeneration, is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disorder in copper metabolism and consists of copper accumulation in multiple organs (liver, cornea, brain). Its genetic substrate is the mutation of gene ATP7B with predominantly hepatic expression. The expression of this gene represents an intracellular transporter, which, in a healthy patient, transports copper to apocerulo-plasmin, where ceruloplasmin is formed. ATP7B also facilitates the transport of copper in the bile. The genetic defect leads to dysfunction of this transporter, thus copper accumulating in the cell results in its destruction. In the absence of the proper treatment, free copper enters the bloodstream and accumulates in the organs. Systemic copper storage has a varied phenotype, from asymptomatic forms to liver and neuropsychiatric damage [

1].

Positive diagnosis is, in most cases, delayed or overlooked due to the variety of symptoms and signs. Due to misdiagnosis or a prolonged initial period of silence, WD is often detected too late. A delayed diagnosis is a key risk factor for a poor treatment outcome. There is great variability of symptoms in WD that most commonly present between the ages of 5 and 35 years.[

2]

WD results from mutations in the ATP7B gene that is designed to synthesize the copper transporter protein. As a result of these mutations, an imbalance in copper metabolism occurs, leading to the impossibility of removing it from the body and accumulation of excess levels in the cell. Enterically, the specific copper transporter 1 (CTR1) and the non-specific DMT1 absorb copper from the intestinal lumen. Reductases are needed for copper to be absorbed into the enterocyte where the copper interacts with the chaperon protein to be stored intracellularly. Oxidized copper binds to proteins such as albumin or alpha2-macroglobulin for transport. Portal circulation directs the greatest amount of copper to the liver [

3].

In the liver cell, under physiological conditions, the copper coming through the portal route enters the cell through copper transporter CTR1 located at the apical pole. Thus, copper enters the cytosol, where it binds to the chaperon protein ATOX1. This transports copper to ATP7B, a transporter that sends the copper molecule into the Golgi apparatus. There it is incorporated into apocerulo-plasmin, which has 8 copper binding sites. Thus, apocerulo-plasmin becomes ceruloplasmin, which will transport the copper molecules back to the plasma through the latero-basal pole. An alternative route would be the exocytosis of copper unattached by ceruloplasmin (excess copper), through the canalicular membrane into the bile. The bile duct is vital for controlling hepatic copper levels. Moreover, ATP7B acts as a conveyor here. [

4]

WD is found everywhere globally, with a prevalence that varies and has increased over time due to much more effective diagnostic methods, with recent studies suggesting it to be between 1:40,000-1:60,000. In Europe it is estimated to be around 1:40,000-1:50,000, with dominant areas such as Sardinia with a prevalence of 1:16,000. The highest incidence in the world was reported in Costa Rica (4.9 per 100,000 inhabitants). In Europe, the disease is more commonly diagnosed in Germany (2.5 per 100,000 inhabitants) and Austria (3.0 per 100,000 inhabitants) [

5].

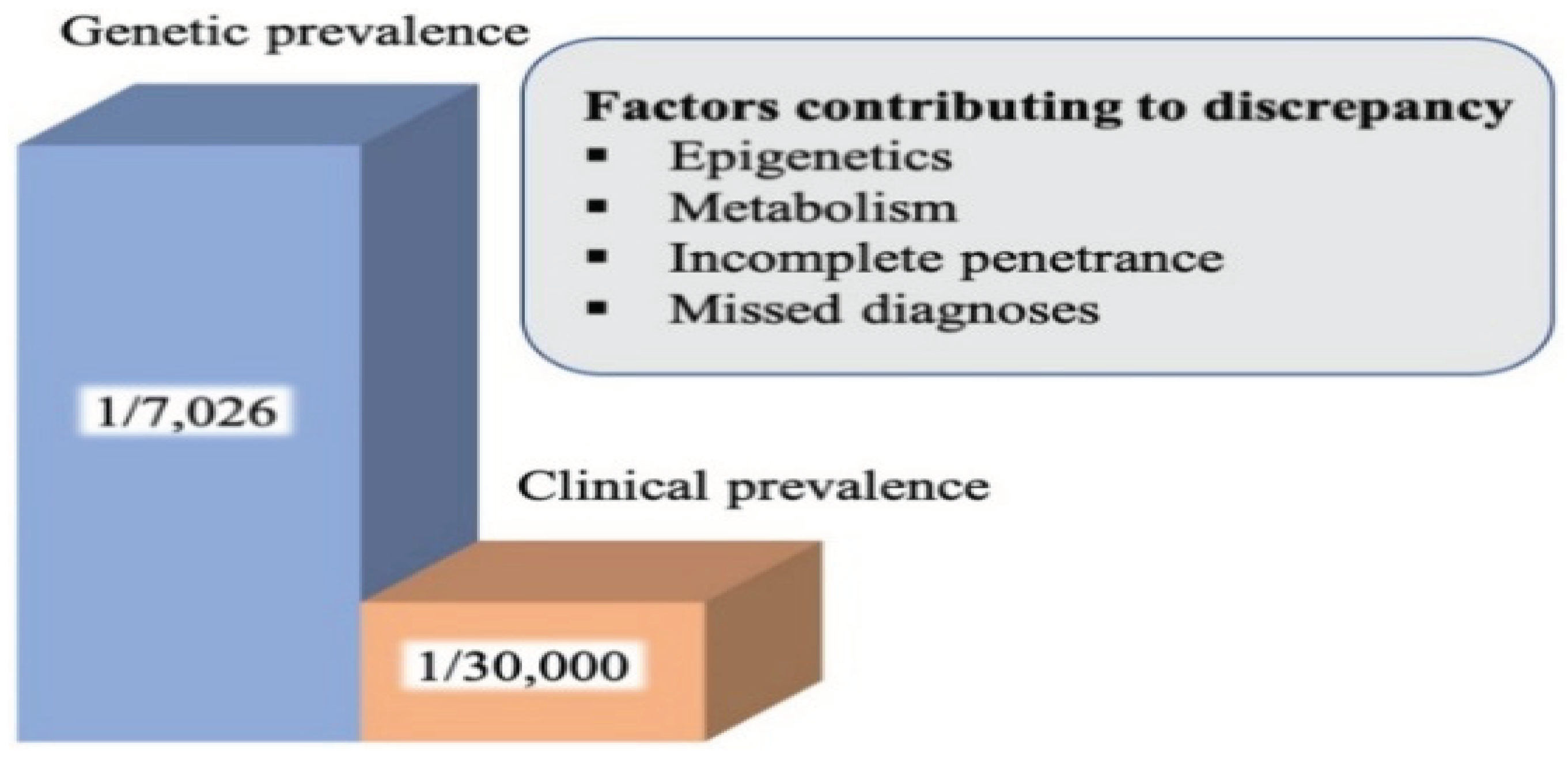

Studies conducted in France and Sardinia suggest that genetic prevalence could be 3-4 times higher than clinical prevalence. The prevalence in France is estimated to be 1:63,000, in Taiwan 1:55,000, and in Hong Kong 1: 40,000, but, nevertheless, there have also been overlooked cases. In Taiwan the female/ male ratio is 1/1.75 suggesting a number of undiagnosed cases among female populations because the female/ male ratio is 1 in other patient groups. In the French study, prevalence was higher in the younger age group, near large cities, the highest age group being 20–29-year-olds (1:37,000) [

6]. In addition, a study conducted in France found that 1 in 31 is a heterozygous carrier [

7], corresponding to a prevalence of 1:1000 births. The discrepancy between the frequency of heterozygous carriers and the prevalence of WD suggests incomplete penetrance of the disease, but further studies are needed [

8]. The factors contributing to this discrepancy include the body’s particular response to copper metabolism, epigenetic factors or misdiagnosis with another metabolic syndrome [

9]

Figure 1.

The difference between clinically diagnosed and genetic prevalence.[

9]

.

Figure 1.

The difference between clinically diagnosed and genetic prevalence.[

9]

.

Epigenetic changes are caused by environmental factors such as diet, stress, exercise, toxins. These can diminish or exacerbate the clinical presentation and progression given by the accumulation of copper in WD.

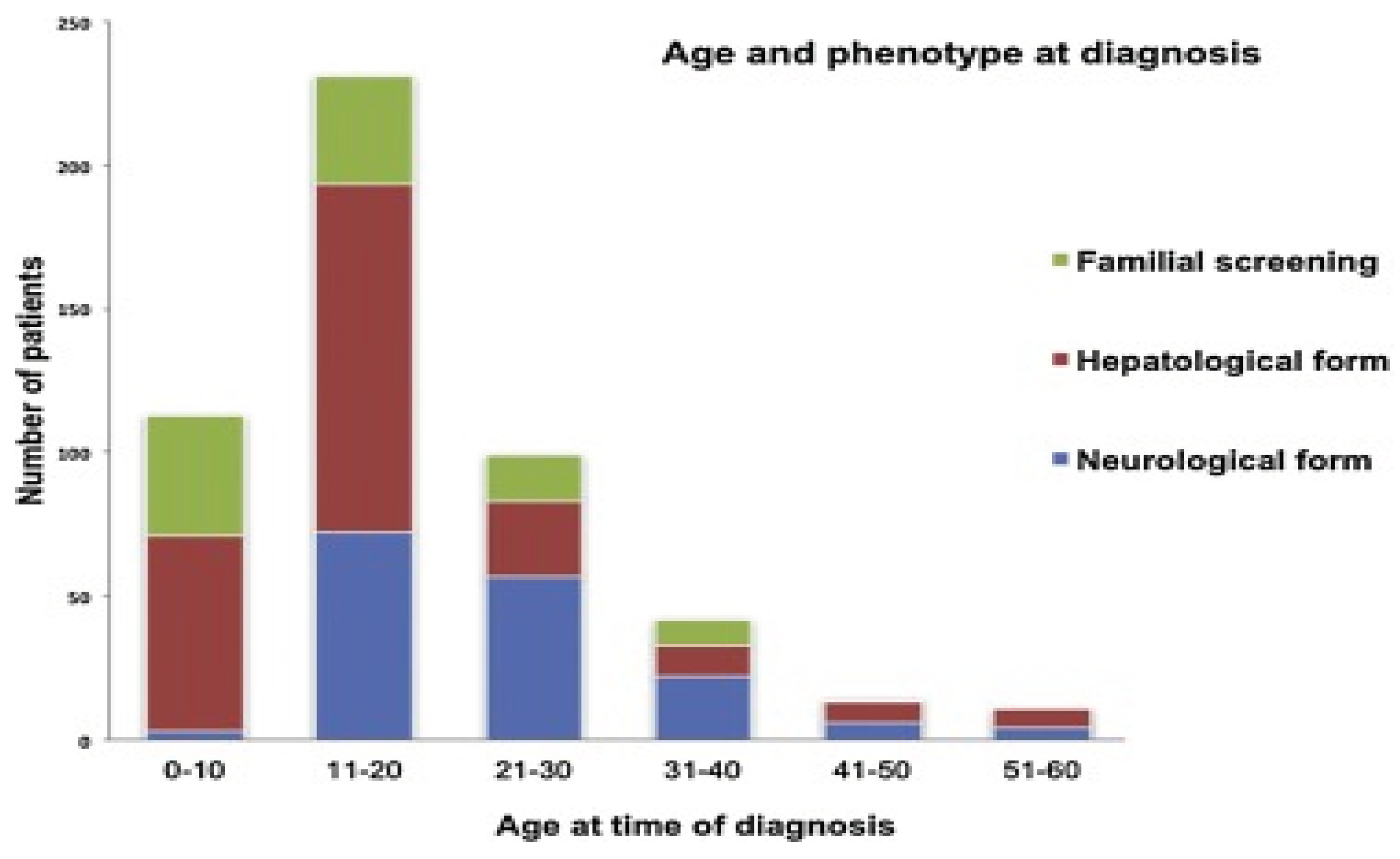

Figure 2.

Age and phenotype at WD diagnosis according to a study conducted in tertiary centers in Greece over the past 30 years. [

10]

.

Figure 2.

Age and phenotype at WD diagnosis according to a study conducted in tertiary centers in Greece over the past 30 years. [

10]

.

Our interest in this topic is due to the fact that the condition is understudied both nationally and globally. Romania lacks a diagnosis protocol and database for this disease. The fact that the condition is understudied nationally makes it an area of important research interest. We also believe that this study will have a positive and innovative impact on the national literature, being the first study in Romania that aims to analyze this condition from an epidemiological point of view. The aim of the present study is to investigate the severity of WD in patients in Romania.

2. Materials and Methods

The study included 67 patients diagnosed with WD between the ages of 7 and 56 years and was conducted from September 19, 2022 to December 20, 2023. Data collection was performed via an online form consisting of 32 questions in a group with people suffering from WD. The survey included questions about demographics, signs of disease and symptoms, laboratory tests, hedero-colateral history, any treatment administered or access to treatment throughout the year, diet, other opinions or comments related to the particularity of the respondent’s case. Anonymity and confidentiality of responses were ensured.

3. Results

Data on the demographic distribution and symptoms of the participants are shown in

Table 1.

Information on the hereditary history, methods of investigation and treatment applied to the participants, are expressed in

Table 2.

In

Table 3 is there the presence of the Kayser-Fleischer ring in relation to the symptoms.

Some testimonials of study participants suffering from WD will be included below. These testimonials encompass the burden of the disease, the everyday problems that patients face.

“I would like to mention that as soon as I was diagnosed with Wilson disease, I was given cuprenil, but my symptoms worsened, my tremors got stronger, I could barely speak and walk, I had no control over my saliva, which made me stop the treatment. In 1992 I managed to be hosptalized in a clinic in Germany, here I was given metal-captase (D-penicillamine 300 mg) in combination with zinc and vitamin B6, this combination brought fantastic results in a year. I would also add that until 2002 my treatment was supported by the German Red Cross. And since 2005 I have been living in Germany, marrying a German citizen who also has Wilson disease)”

“There were times when I did not have easy access to treatment.”

“Many times I have had backs turned to me. I cannot find doctors who want to take care of me because they do not have the necessary skills. They refer me from one to the another. They even told me it was a miracle that I was stable and that the diagnosis was wrong. I was left with the same treatment as 7 years ago because as an adult I did not find a doctor who wanted to get involved.”

“There is no treatment in all the cases and genetic testing is not done for free as it is done in other countries. Being a rare disease, genetic testing for it should be free.”

“Receiving the treatment is very difficult because it is not provided in the country and when the pharmacies in the city receive the medication they prefer to say that they do not work with the distributor who has them. So I buy the treatment from Spain.”

“In the year 2000-2001 in Romania, genetic tests for the detection of the disease could not be performed. Ceruroplasmin and cupruria were not easy to perform. I was diagnosed at AKH in Vienna. I am also addicted to trientine, which, as you know, is not found in Romania and is extremely expensive (I get it through the Compassionate Programme from Univar). I am allergic to D-penicillamine (medullary aplasia, rash on the face, etc.).”

“The Ministry of Health should include the mandatory blood and urine copper test in children after they reach the age of 3, in order for early detection and the provision of more information about this disease.”

“The sad thing is that I had to leave the country and move to Spain to have access to treatment and save my life.”

“Predominantly the psychic form at the onset of the disease, the neuropsychic form at the time of diagnosis, and the neuropsychic and hepatic form following discontinuation of treatment for 3 months. Diseases secondary to Wilson disease subsequently surfaced: epilepsy, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, neuropathy, renal microlithiasis, HTA and tachycardia, cervical spondylosis, mild cerebral atrophy, and dystonia. After discontinuing the treatment for 3 months as recommended by a neurologist, in about 2 months I developed a hepatic form with hepatic steatosis and increased transaminases. All three forms of Wilson disease improved after about 1 year after resuming chelating treatment with cupripen reintroduced by the gastoenterologist.”

“Cupripen is difficult to find in pharmacies, zinc and hepatoprotector should be reimbursed taking into account that it a treatment for life.”

4. Discussion

There is no significant gender difference in our study, with the female sex 52.2% (35 participants) compared to the male sex 47.8% (32 participants). One study in Serbia featured 54.9% male and 45.1% female participants. [

11]

Regarding the environment of origin, 40 participants (59.7%) come from urban areas and the remaining 27 participants (40.3%) from rural areas.

Because WD is a degenerative disease it is very important that the diagnosis be early, in our study the mean age of diagnosis was 20 years with the minimum age of 6 years and the maximum of 53 years, an increased mean age compared to the Sardinian study where the mean age was 15 years and 6 months with the minimum age 4 years and 1 month and the maximum 44 years.[

12]

The most common symptoms in the participants in our study were liver-related along with the neurological ones with 22 (32.8%) cases, neurological damage was met in 18 (26.9%) cases, 15 (22.4%) cases presented liver damage. Liver, neurological, and psychiatric damage was met in 5 (7.5%) cases, one case (1.5%) presented a hepatic and psychiatric form, and 5 (7.5%) were asymptomatic cases. Compared to the study conducted in Sardinia [

12] where the most common symptoms were the hepatological and neurological ones with 26 (38.23%) cases, 20 (29.41%) cases had hepatic presentation and we noticed that neurological manifestations were lower compared to our study and occurred in only 7 (10.29%) cases, and 15 (22.05%) asymptomatic cases, which is 3 times higher compared to our study, as such, we can infer that there was a lack in early diagnosis in our study.

The earlier the diagnosis, the more effective the treatment. In our study 40.3% of cases were diagnosed in less than one year, 40.3% in 1-2 years, 15% were diagnosed between 2-10 years, and 3% in over 10 years. A very important thing to note is that 44.8% of the participants of our study had an initial wrong diagnosis, a contributing factor to this may be the polymorphism of clinical manifestations. The most common method of diagnosis among participants was copper in the urine on 24h, with 93% of cases, followed by copper in the blood 90% of cases, ceruloplasmin in the blood 90% of participants, imaging studies (MRI, CT, ultrasound) 76.5% of participants, eye examination 84% of participants, 39% of participants had genetic testing, and 24% of participants had liver biopsy.

The only current screening method that can be performed in children is genetic testing. Among the study participants who had children, only 10.4% had their genetic testing performed. Of the study participants, 29.9% still had cases of WD in the family, the most common among siblings (55%), cousins (50%), and parents (20%).

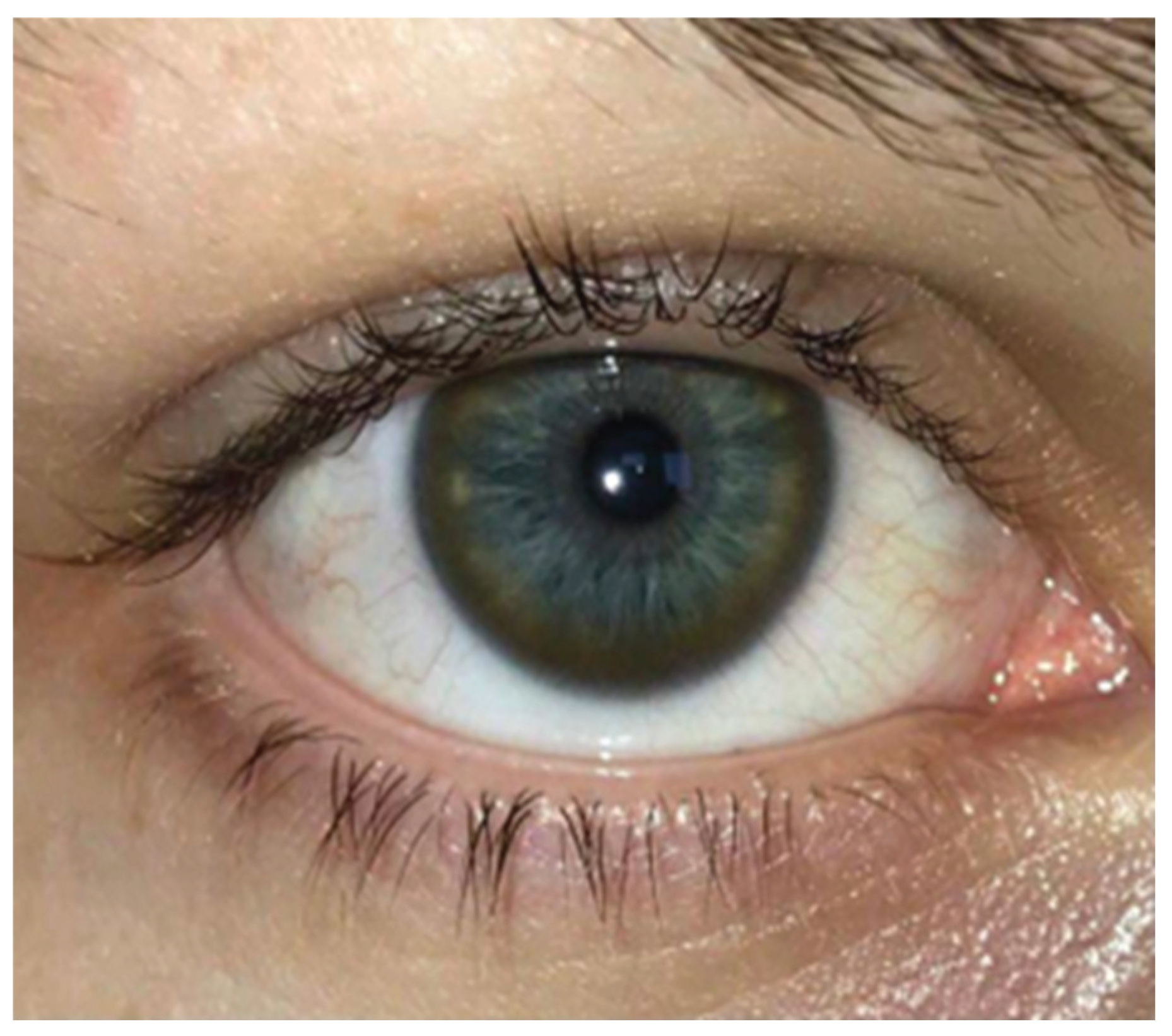

A pathognomonic sign in WD is the Kayser-Fleisher ring, correlated with the symptoms, in our study occuring in 50.7% of the participants. This was most commonly encountered in the participants with neurological and hepatic symptoms 61.7%, in those with only liver damage the Kayser-Fleischer ring was present in 44.1%, of the participants with psychiatric, hepatological, and neurological symptoms 14.7% presented the ring, in cases with only neurological damage the ring was present in 52.9% of cases, and in those with liver and psychiatric damage it was present in 2.9% of cases.

Figure 3.

Complete Kayser-Fleischer ring on a blue eye (photo provided by one of the study participants).

Figure 3.

Complete Kayser-Fleischer ring on a blue eye (photo provided by one of the study participants).

Regarding the fertility rate among the participants, 17 (25.4%) of the 67 participants in the study had children.

Up to 30% of WD patients may first experience psychiatric symptoms, according to epidemiological research. The earliest psychiatric symptom may present in youth with a loss of academic performance, aggressiveness, impulsive irritability, antisocial behavior. The most common signs of psychiatric disorders in WD are mood swings. Between 4% and 16% of WD patients attempt suicide, while between 20% and 60% of WD patients experience depression over the course of the disease [

13].

In our study, 37.3% of participants claimed to be experiencing depression. Of those experiencing depression only 16.4% were undergoing antidepressant treatment. About half of the study participants (49.3%) claimed that they swung quickly from one mood to another, this having an unfavorable impact on the quality of life. At the same time, 38.8% of the study participants believed that they displayed impulsive behavior.

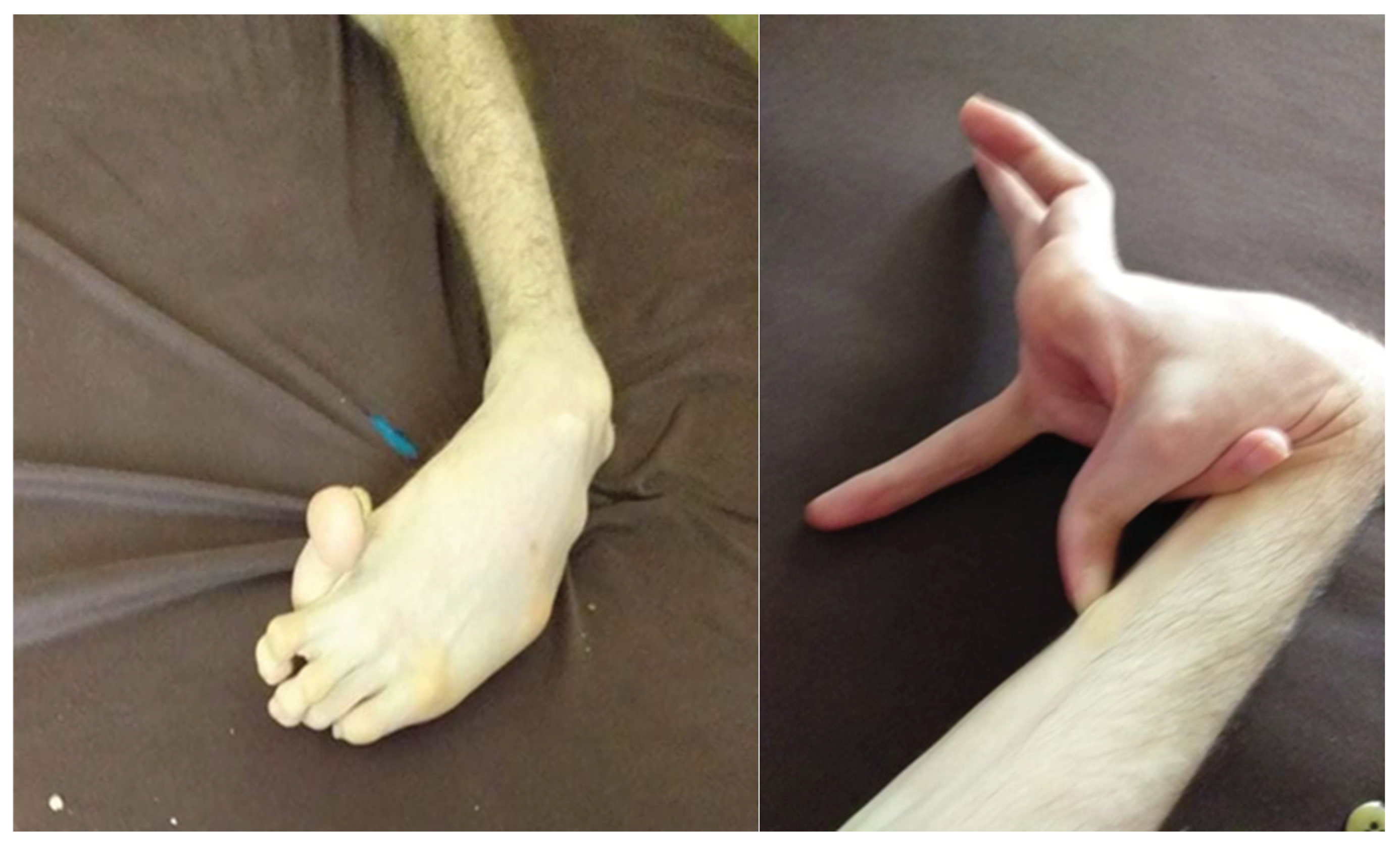

The most common neurological symptoms in the cases analyzed in our study were muscle stiffness (49.5%), followed by tremor (45%), speech disorders (40.5%), sialorrhea (39%), reduced facial expression (33), and the least frequently encountrered one was involuntary movement of the hand (31.5%).

In a Polish cohort study, which analyzed neurological manifestations in patients with WD, the most common neurological symptoms were dysarthria (73.6%), followed by tremor (69.8–71.7%), muscle stiffness (66%), reduced facial expression (66%) [

14].

A classic sign of WD is facial dystonia known as risus sardonicus or “Wilson’s face” which consists of an excessively forced smile.

Figure 4.

WD characteristic sign of risus sardonicus in a 37-year-old man.

Figure 4.

WD characteristic sign of risus sardonicus in a 37-year-old man.

Figure 5.

Dystonia of the left upper limb and left lower limb in a patient with WD.

Figure 5.

Dystonia of the left upper limb and left lower limb in a patient with WD.

The images belong to our archive, supplemented by contributions from study participants who willingly granted their consent for publication.

A risk factor in the occurrence of WD is consanguinity. In patients in our study, consanguinity was present in 5 (7.5%) cases.

Treatment in WD is laborious. The first intention is the drug treatment that consists of copper chelators to which the hygienic-dietary treatment is added which consists of eliminating foods rich in copper. Symptomatic treatment is added to these. Patients with neurological suffering are recommended sessions of physical therapy, hydrotherapy, while those with speech disorders are recommended speech therapy.

The most common drug treatment used among study participants was D-penicillamine (46.3% of cases), followed by D-penicillamine, and zinc (28.3% of cases), 10.4% of cases used trientine as chelating treatment, zinc and trientine in 6% of cases, only zinc in 6% of cases, D-penicillamine and Trientine in 1.5% cases, D-penicillamine and zinc in 1.5% cases.

In a study in France the most used treatment was D-penicillamine (30.5%), followed by Trientine (14.70%), and zinc acetate (13.0%) [

7].

In Romania, 22.4% of the cases that participated in the study do not have access to treatment throughout the year. Also, in the administration of the treatment, it is important to have a lunch break for a more efficient absorption. In our study, 64.2% of the patients took this break.

In WD hygienic-dietary regime is also important and it consists of avoiding foods that have a high copper content. In our study, more than half of the cases (61.2%) only partially followed the dietary plan, avoiding only a few foods rich in copper, 26.9% of cases strictly followed it and analyzed everything they ate, and 11.9% did not follow the plan, considering that drug treatment was sufficient.

For a better recovery of the degree of invalidity, sessions of physical therapy, hydrotherapy, speech therapy are indicated. In our study, 28.4% resorted to recovery sessions and most (13.4%) from the time of diagnosis to the present, 9% under 6 months, 6.5% between 6 months and one year, and 1.5% resorted to recovery sessions until the symptoms improved.

5. Conclusions

The severity of WD is based on many aspects, the most important being early diagnosis and access to treatment throughout the year. The prognosis is favorable with early diagnosis and treatment, but it is crucial to diagnose individuals before they develop major symptoms. Therefore, advances in WD screening can lead to an earlier diagnosis and better results.

The rate of overlooking the diagnosis is high in Romania but also globally, as a result, it is important to take WD into account when encountering hepatitis type liver damage, liver failure, and neurological symptoms such as tremor, muscle stiffness, speech disorders in a child or adolescent.

According to the testimonials of the participants in our study, they have difficulty in obtaining the treatment, they are forced to resort to sources from abroad, thus, in Romania, the Ministry of Health should permanently ensure an alternative range of medicines that meet the needs, deliver the required quantities in the shortest term and oblige the pharmaceutical units to stock up on medicines if they are not in stock when requested.

WD is a complex disease, the diagnosis being a challenge that requires a multidisciplinary team consisting of neurologist, gastroenterologist, psychiatrist, psychologist, ophthalmologist, pediatrician in order for the treatment to have a good outcome.

Improving treatment rates, raising patient awareness, educating patients about the long-term impact of the disease, or developing a new treatment paradigm could make a significant contribution to reducing the burden of the disease.

It is necessary to implement a national registry that comprises WD patients in Romania in order to have a record of the number of cases, the treatment administered, and each patient’s evolution.

Also, the establishment of an association to support patients in procuring the treatment, the last generation being very costly.

Another measure would be mass population screening, except that there is not yet a cost-effective method available. Although the optimal time for screening is questionable, a child’s 3-year period would be the most indicated. All WD patients should undergo screening tests for depression and those who have psychiatric disorders should be treated with appropriate treatment. Cognitive function should be routinely assessed and psychological counseling is recommended for both the patient and their family.

In order to provide an early and effective preventive therapy that can significantly improve outcomes in WD patients, new biomarkers and the development of new techniques should be continuously investigated worldwide.

There are few WD studies conducted in Romania, therefore more studies are needed to analyze the complexity of this condition, studies which should result in ways to improve the patient’s quality of life and offer them a life span close to that of a healthy person.

Author Contributions

The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, LM, IRM, TSV; methodology, LM, IRM, TSV; validation, LM, MAB, IRM, TSV; formal analysis, IRM, TSV; investigation, LM, MAB, IRM, TSV; resources, LM, MAB; data curation, LM, MAB; writing—original draft preparation, LM, MAB, IRM, TSV; writing—review and editing, LM, MAB, IRM, TSV; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study”.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Aurélia Poujoisa, France Woimanta, Solène Samson, Pascal Chaine, Nadège Girardot-Tinanta, Philippe Tuppin. Characteristics and prevalence of Wilson’s disease: A 2013 observational population-based study in France. Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology Volume 42, Issue 1, February 2018, Pages 57-63. [CrossRef]

- Relu Cocoș, Alina Şendroiu, Sorina Schipor, Laurentiu Camil Bohîltea, Ionuț Şendroiu, Florina Raicu. Genotype-phenotype correlations in a mountain population community with high prevalence of Wilson’s disease: Genetic and clinical homogeneity Plous One.4 June 2014. [CrossRef]

- Fei Wu, Jing Wang, Chunwen Pu, Liang Qiao, and Chunmeng Jiang. Wilson’s Disease: A Comprehensive Review of the Molecular Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2015 Mar; 16(3): 6419–6431. [CrossRef]

- Wolfgang Stremmel, Ralf Weiskirchen. Therapeutic strategies in Wilson disease: pathophysiology and mode of action. Ann Transl Med. 2021 Apr; 9(8): 732. [CrossRef]

- Beata Kasztelan-Szczerbinska* and Halina Cichoz-Lach Wilson’s Disease: An Update on the Diagnostic Workup and Management, J Clin Med. 2021 Nov; 10(21): 5097. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Damgaard Sandahl, Tea Lund Laursen, Ditte Emilie Munk, Hendrik Vilstrup, Karl Heinz Weiss, Peter Ott, The Prevalence of Wilson’s Disease: An Update HEPATOLOGY, volume 71, February 2020 Pages 722-732. [CrossRef]

- P de Bie, P Muller, C Wijmenga, and L W J Klomp. Molecular pathogenesis of Wilson and Menkes disease: correlation of mutations with molecular defects and disease phenotypes. J Med Genet. 2007 Nov; 44(11): 673–688. [CrossRef]

- Pascual Lorente-Arencibia, Luis García-Villarreal, Rafaela González-Montelongo, Luis A Rubio-Rodríguez, Carlos Flores, Paloma Garay-Sánchez et al- Wilson Disease Prevalence: Discrepancy Between Clinical Records, Registries and Mutation Carrier Frequency. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2022 Feb 1;74(2):192-199. [CrossRef]

- Marcia Leung., Paul B. Aronowitz., Valentina Medici. The Present and Future Challenges of Wilson’s Disease Diagnosis and Treatment. Clinical Liver Disease, Apr 2021; 17(4):268. [CrossRef]

- Tampaki, Maria; Gatselis, Nikolaos K.; Savvanis, Spyridon; Koullias, Emmanouil; Saitis, Asterios; Gabeta, Stella et al-Wilson disease: 30-year data on epidemiology, clinical presentation, treatment modalities and disease outcomes from two tertiary Greek centers. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology: December 2020 - Volume 32 - Issue 12 - p 1545-1552. [CrossRef]

- M. Svetel, T. Pekmezović, I. Petrović, A. Tomić, N. Kresojević, R. Ješić, et al- Long-term outcome in Serbian patients with Wilson disease. European journal of neurology Volume 16, Issue 7 Pages: 775-883, i, e122-e145 July 2009. [CrossRef]

- Giagheddu, L. Dernelia, G. Puggioni, A. M. Nurchi, L. Contu, G. Pirari, A. Deplano and M. G. Rachele Epidemiologic study of hepatolenticular degeneration (Wilson’s disease) in Sardinia (1902-1983) Acta Neurol Scand., 1985:72:43-5. [CrossRef]

- Tomasz Litwin, Petr Dusek, Tomasz Szafrański, Karolina Dzieżyc, Anna Członkowska, and Janusz K. Rybakowski Psychiatric manifestations in Wilson’s disease: possibilities and difficulties for treatment Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2018 Jul; 8(7): 199–211. [CrossRef]

- Tampaki, Maria; Gatselis, Nikolaos K.; Savvanis, Spyridon; Koullias, Emmanouil et-al Wilson disease: 30-year data on epidemiology, clinical presentation, treatment modalities and disease outcomes from two tertiary Greek centers: European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Volume 32, Number 12, 14 August 2020, pp. 1545-1552(8). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).