Submitted:

12 March 2024

Posted:

12 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drugs and Administration

2.2. Patients and Diagnostic Procedures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

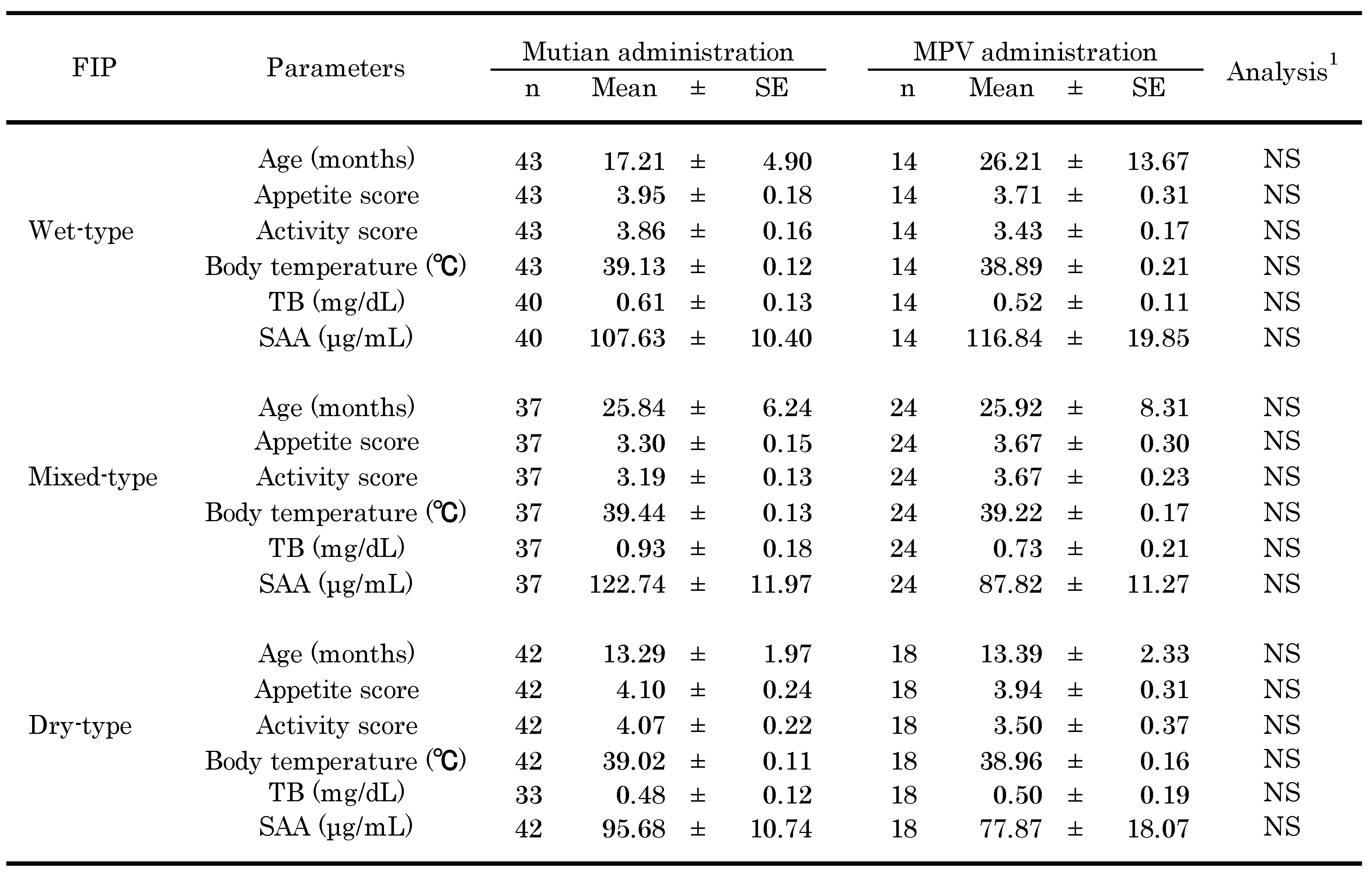

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Observed Participants

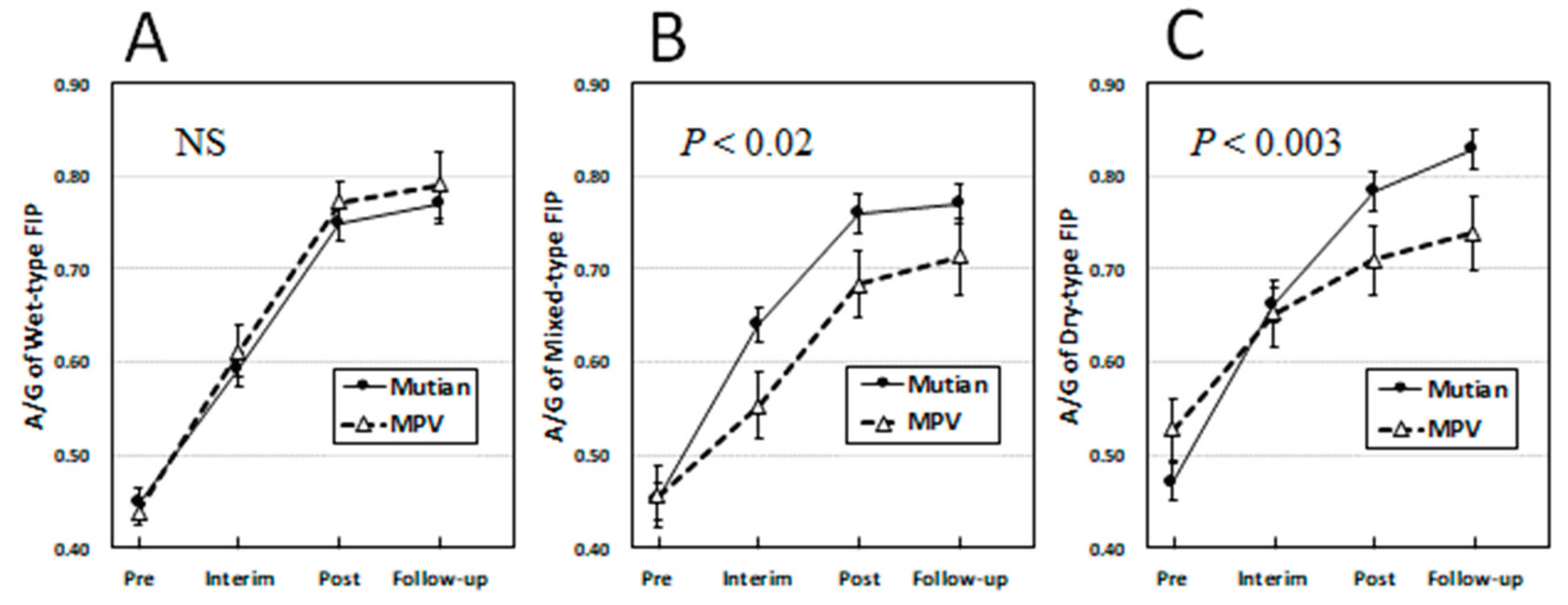

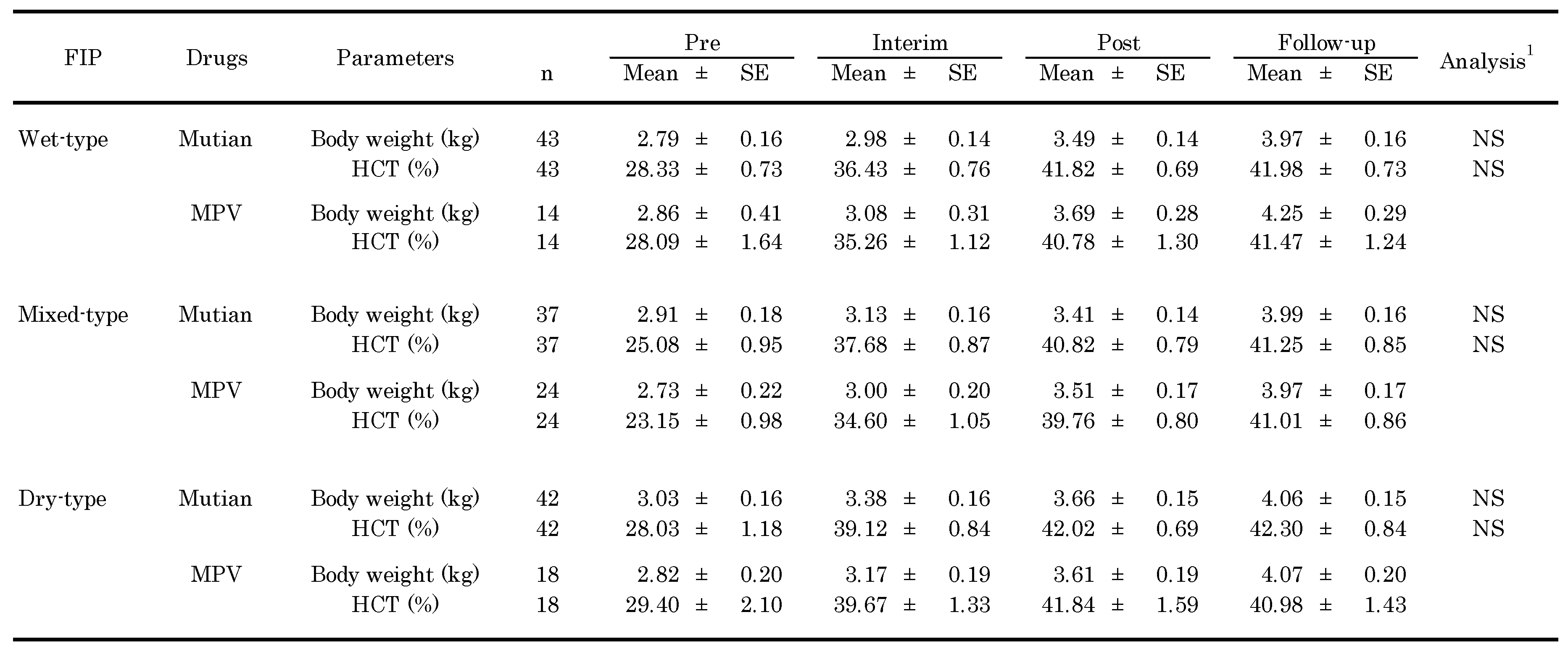

3.2. Changes of Clinical Parameters Over Times

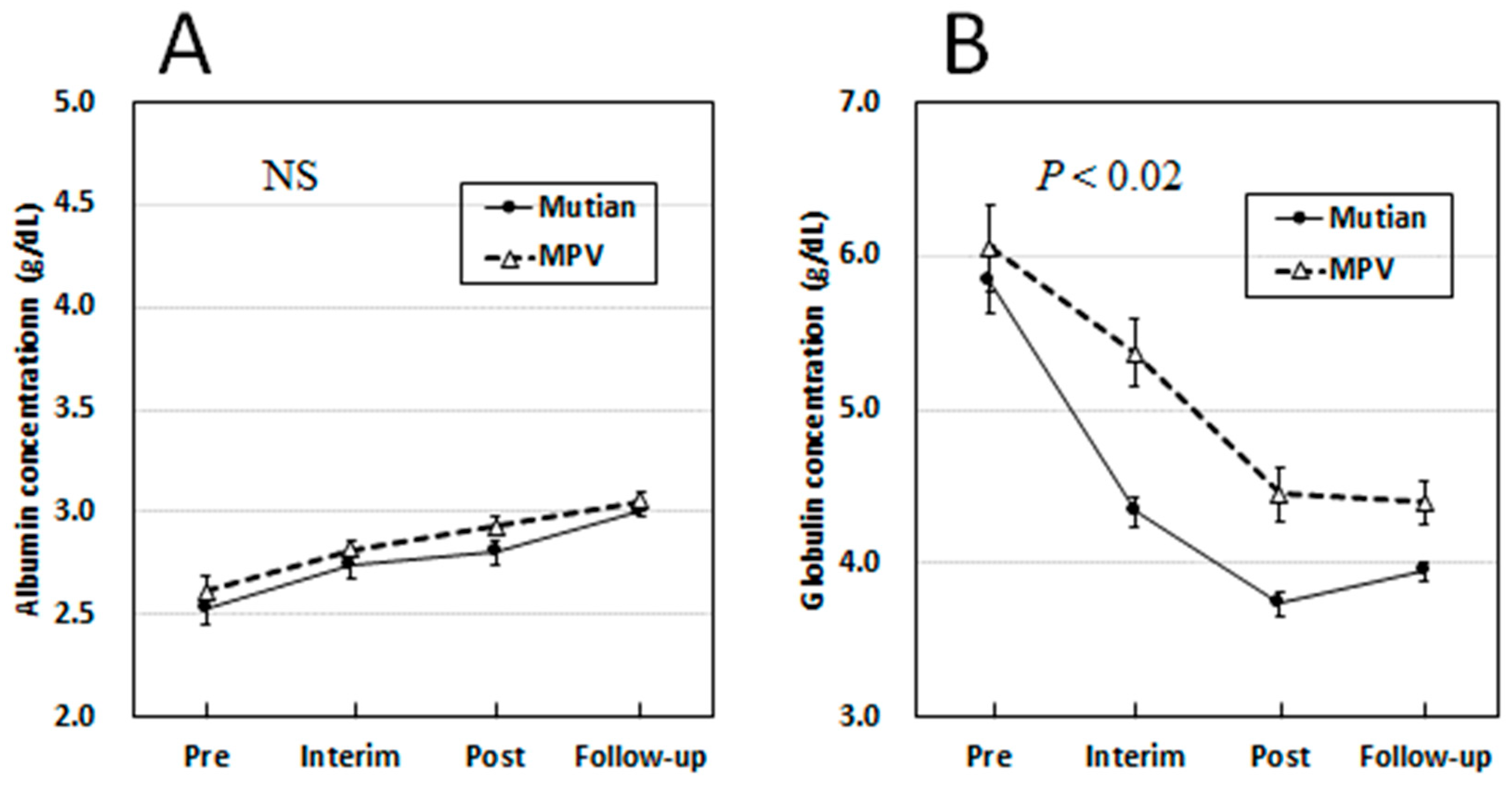

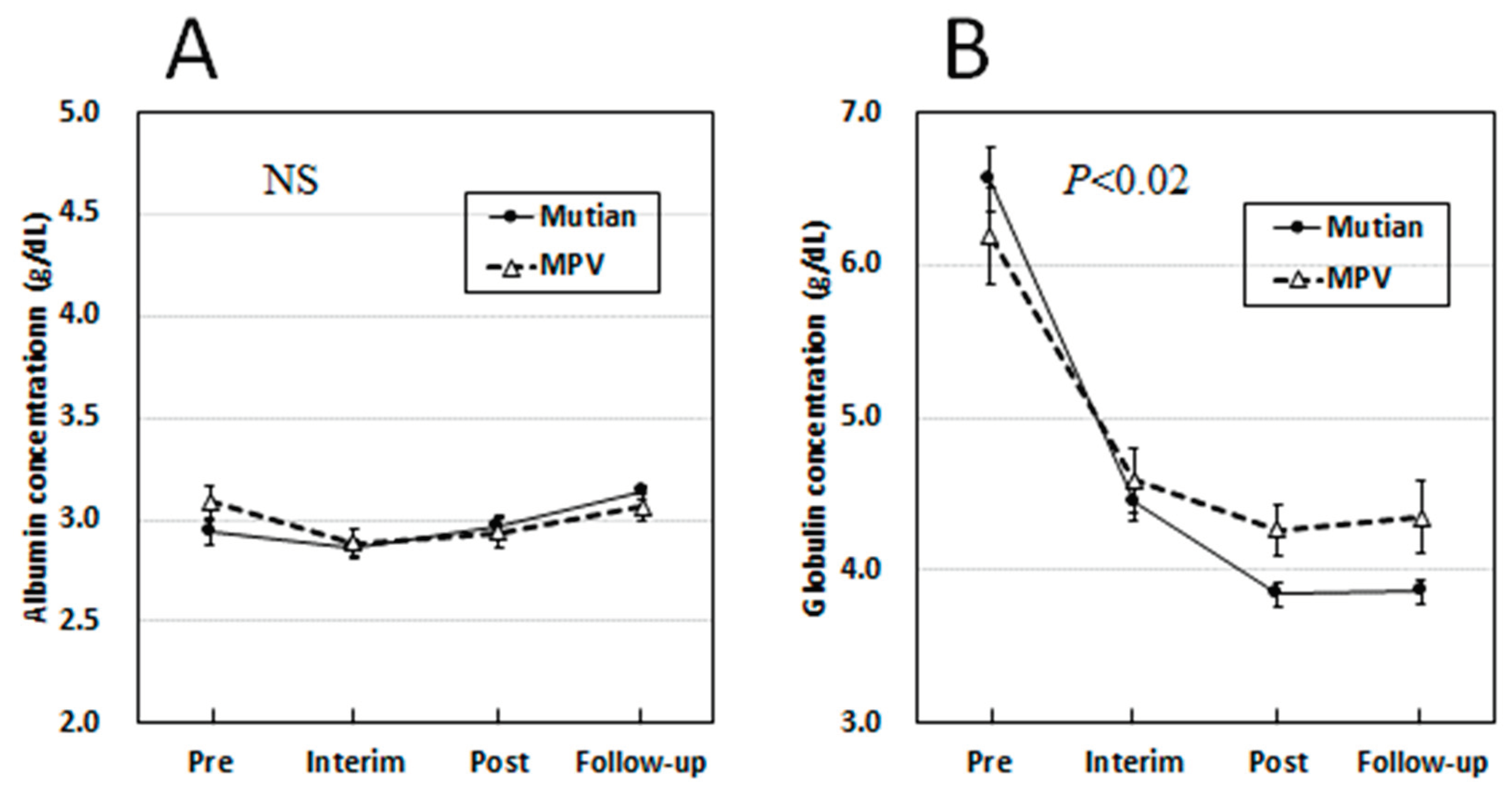

3.3. Changes of Albumin and Globulin Levels in Circulation Over Times

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pedersen, N.C. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection: 1963-2008. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 225–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekes, G.; Thiel, H.J. Feline coronaviruses: pathogenesis of feline infectious peritonitis. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 96, 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Thayer, V.; Gogolski, S.; Felten, S.; Hartmann, K.; Kennedy, M.; Olah, G.A. 2022 AAFP/everycat feline infectious peritonitis diagnosis guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2022, 24, 905–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipar, A.; Meli, M.L. Feline infectious peritonitis: still an enigma? Vet. Pathol. 2014, 51, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, N.C. An update on feline infectious peritonitis: diagnostics and therapeutics. Vet. J. 2014, 201, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felten, S.; Hartmann, K. Diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis: a review of the current literature. Viruses. 2019, 11, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addie, D.; Belák, S.; Boucraut-Baralon, C.; Egberink, H.; Frymus, T.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.; Hartmann, K.; Hosie, M.J.; Lloret, A.; Lutz, H.; et al. Feline infectious peritonitis. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn-Moore, D.; Barker, E.; Taylor, S.; Tasker, S.; Sorrell, S. An update on treatment of FIP in the UK. Vet. Times. 2024, 51, 8–11. Available online: https://www.vettimes.co.uk/article/an-update-on-treatment-of-fip-in-the-uk-cpdfip/ [Accessed February 9, 2024].

- Ritz, S.; Egberink, H.; Hartmann, K. Effect of feline interferon-omega on the survival time and quality of life of cats with feline infectious peritonitis. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2007, 21, 1193–1197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Sato, Y.; Osawa, S.; Inoue, M.; Tanaka, S.; Sasaki, T. Suppression of feline coronavirus replication in vitro by cyclosporin A. Vet. Res. 2012, 43, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.G.; Perron, M.; Murakami, E.; Bauer, K.; Park, Y.; Eckstrand, C.; Liepnieks, M.; Pedersen, N.C. The nucleoside analog GS-441524 strongly inhibits feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) virus in tissue culture and experimental cat infection studies. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 219, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.J.; Won, J.J.; Graham, R.L.; Dinnon, K.H., 3rd.; Sims, A.C.; Feng, J.Y.; Cihlar, T.; Denison, M.R.; Baric, R.S.; Sheahan, T.P. Broad spectrum antiviral remdesivir inhibits human endemic and zoonotic deltacoronaviruses with a highly divergent RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Antiviral Res. 2019, 169, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, E.S.; Levy, J.K. Current knowledge about the antivirals remdesivir (GS-5734) and GS-441524 as therapeutic options for coronaviruses. One Health. 2020, 9, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, N.C.; Perron, M.; Bannasch, M.; Montgomery, E.; Murakami, E.; Liepnieks, M.; Lie, H. Efficacy and safety of the nucleoside analog GS-441524 for treatment of cats with naturally occurring feline infectious peritonitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2019, 21, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, P.J.; Bannasch, M.; Thomasy, S.M.; Murthy, V.D.; Vernau, K.M.; Liepnieks, M.; Montgomery, E.; Knickelbein, K.E.; Murphy, B.; Pedersen, N.C. Antiviral treatment using the adenosine nucleoside analogue GS-441524 in cats with clinically diagnosed neurological feline infectious peritonitis. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addie, D.D.; Covell-Ritchie, J.; Jarrett, O.; Fosbery, M. Rapid resolution of non-effusive feline infectious peritonitis uveitis with an oral adenosine nucleoside analogue and feline interferon omega. Viruses. 2020, 12, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addie, D.D.; Curran, S.; Bellini, F.; Crowe, B.; Sheehan, E.; Ukrainchuk, L.; Decaro, N. Oral Mutian®X stopped faecal feline coronavirus shedding by naturally infected cats. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 130, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, M.; Uemura, Y. Therapeutic effects of Mutian® Xraphconn on 141 client-owned cats with feline infectious peritonitis predicted by total bilirubin levels. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, M.; Uemura, Y. Prognostic prediction for therapeutic effects of Mutian on 324 client-owned cats with feline infectious peritonitis based on clinical laboratory indicators and physical signs. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, A.; Gralinski, L.E.; Johnson, C.E.; Yao, W.; Kovarova, M.; Dinnon, K.H., 3rd; Liu, H.; Madden, V.J.; Krzystek, H.M.; De, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection is effectively treated and prevented by EIDD-2801. Nature. 2021, 591, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.E.; Vogel, H.; Castillo, D.; Olsen, M.; Pedersen, N.; Murphy, B.G. Investigation of monotherapy and combined anticoronaviral therapies against feline coronavirus serotype II in vitro. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2022, 24, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krentz, D.; Zenger, K.; Alberer, M.; Felten, S.; Bergmann, M.; Dorsch, R.; Matiasek, K.; Kolberg, L.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Meli, M.L.; et al. Curing cats with feline infectious peritonitis with an oral multi-component drug containing GS-441524. Viruses. 2021, 13, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homepage of Mutian Life Sciences Co., Ltd. Available online: https://www.mutian.com/en/ [Accessed February 9, 2024].

- Addie, D.D.; Silveira, C.; Aston, C.; Brauckmann, P.; Covell-Ritchie, J.; Felstead, C.; Fosbery, M.; Gibbins, C.; Macaulay, K.; McMurrough, J.; et al. Alpha-1 acid glycoprotein reduction differentiated recovery from remission in a small cohort of cats treated for feline infectious peritonitis. Viruses. 2022, 14, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Jacque, N.; Novicoff, W.; Li, E.; Negash, R.; Evans, S.J.M. Unlicensed molnupiravir is an effective rescue treatment following failure of unlicensed GS-441524-like therapy for cats with suspected feline infectious peritonitis. Pathogens. 2022, 11, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, F.; Kuehner, K.A.; Ritz, S.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Hartmann, K. Clinical and laboratory features of cats with feline infectious peritonitis--a retrospective study of 231 confirmed cases (2000-2010). J. Feline Med, Surg. 2016, 18, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G. Acute phase proteins in cats: Diagnostic and prognostic role, future directions, and analytical challenges. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2023, 52 (Suppl. 1), 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Ouyang, H.; Ji, W.; Liu, J.; Liao, X.; Li, J.; Hu, C. A retrospective study of clinical and laboratory features and treatment on cats highly suspected of feline infectious peritonitis in Wuhan, China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sase, O. Molnupiravir treatment of 18 cats with feline infectious peritonitis: A case series. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 1876–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.; Wittenburg, L.; Yan, V.C.; Theil, J.H.; Castillo, D.; Reagan, K.L.; Williams, S.; Pham, C.D.; Li, C.; Muller, F.L.; et al. An optimized bioassay for screening combined anticoronaviral compounds for efficacy against feline infectious peritonitis virus with pharmacokinetic analyses of GS-441524, remdesivir, and molnupiravir in cats. Viruses. 2022, 14, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, P.J. Coronavirus infection of the central nervous system: animal models in the time of COVID-19. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 584673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Peng, W.Y.; Lee, W.H.; Lin, T.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Dalley, J.W.; Tsai, T.H. Biotransformation and brain distribution of the anti-COVID-19 drug molnupiravir and herb-drug pharmacokinetic interactions between the herbal extract Scutellaria formula-NRICM101. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 234, 115499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.; Liang, X.Y.; Zhang, S.; Bao, D.; Zhao, H.; Li, S.B.; Wang, K.; Hu, G.X.; Gao, F.S. An updated review of feline coronavirus: mind the two biotypes. Virus Res. 2023, 326, 199059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focosi, D. Molnupiravir: From Hope to Epic Fail? Viruses 2022, 14, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosaro, E.; Pires, J.; Castillo, D.; Murphy, B.G.; Reagan, K.L. Efficacy of oral remdesivir compared to GS-441524 for treatment of cats with naturally occurring effusive feline infectious peritonitis: a blinded, non-inferiority study. Viruses 2023, 15, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicklbauer, K.; Krentz, D.; Bergmann, M.; Felten, S.; Dorsch, R.; Fischer, A.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Meli, M.L.; Spiri, A.M.; Alberer, M.; et al. Long-term follow-up of cats in complete remission after treatment of feline infectious peritonitis with oral GS-441524. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2023, 25, 1098612X231183250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).