Submitted:

11 March 2024

Posted:

12 March 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Applying Social Resilience Framework Concepts to BGI

2.1. Phase 1: Literature Review to Identify Social Resilience Frameworks

- Identification: An extensive search was conducted through Scopus and Google Scholar databases using the terms “Social” OR “Community” AND “Resilience”, resulting in a large pool of literature, 25,000 Google Scholar and 62,209 Scopus, providing a vast base for initial consideration.

- Screening – The literature review was refined by limiting to the subject areas most closely aligned to BGI and urban planning, such as social science, engineering, environmental science, and multidisciplinary studies, the English language, and journals relating to disaster, risk, and sustainable resilient cities and communities; 3356 articles were identified.

- Eligibility – The titles were screened to narrow the search for the most relevant articles. The title and abstracts of articles that do not relate to social or community resilience, disaster, or sustainability. 175 articles were identified.

- Inclusion – The abstracts of the 175 articles were reviewed, and 23 articles were selected, based on their inclusion of community, social, and/or disaster resilience in their title. From these articles, two were selected for detailed analysis. The first, proposed by Saja et al. (2018), is distinguished by its breadth, derived from the most comprehensive review of existing frameworks synthesizing themes. The second framework by Kwok et al. (2016), grounded in practitioner perspectives, notably incorporates subjective dimensions and normative indicators, distinguishing it from most existing frameworks They are summarized with critical learnings for application to the BGI context.

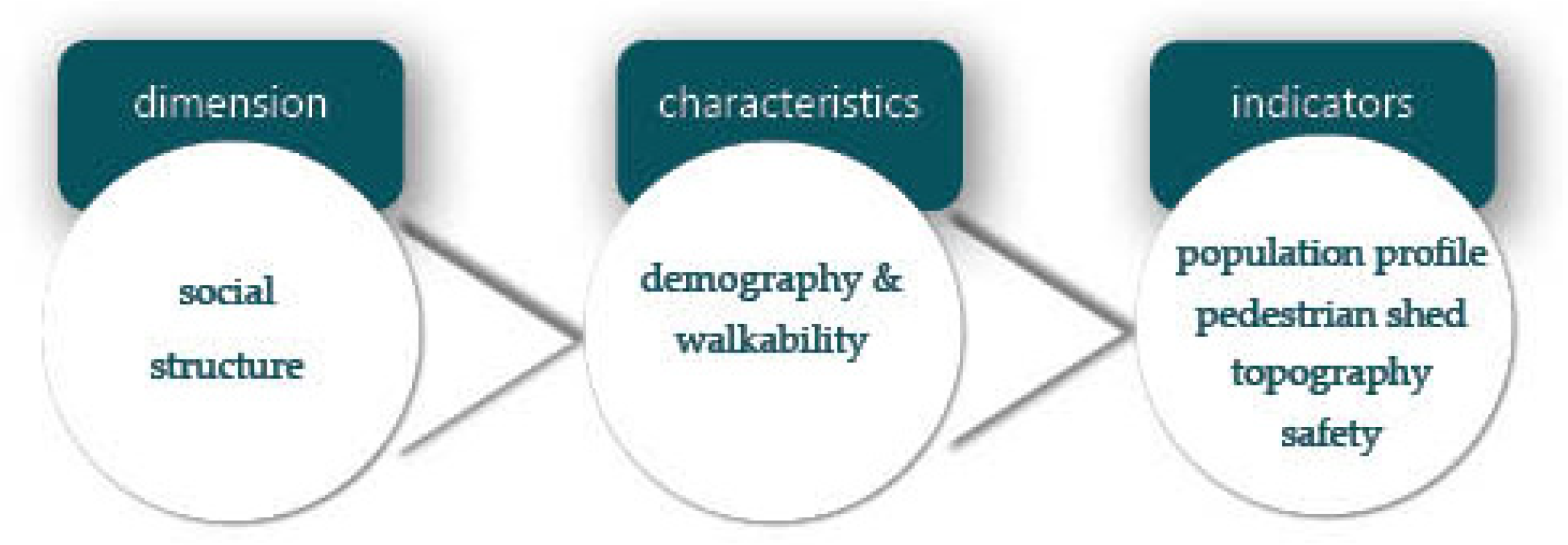

2.2. Phase 2: Adapting Social Resilience Characteristics and Indicators to the BGI Context

2.3. Phase 3: Developing the BGI Social Resilience Framework

3. Results

3.1. Challenges and Complexities in Defining and Operationalizing Social Resilience across Disciplines

3.1.1. Conceptualization and Context

- Capital based – emphasis on social capital with different types of social assets that can be attributed to key social resilience characteristics.

- Coping, adaptive, transformative (CAT) capacities – captures dynamic attributes of social systems on multiple scales.

- Social & interconnected community resilience – social resilience within a holistic, multidimensional characteristic of community resilience.

- Structural & cognitive dimensions – discrete features of a social entity, people, and communities (structural) and attitudes, values, beliefs, and perceptions (cognitive).

3.1.2. Methodology & Indicators

- ▪

- Outcome indicators capture the static results or how well processes, interventions, or programs accomplish a proposed result. They represent the final or observable outcomes to achieve or measure. Outcomes include faster recovery time, improved well-being, community cohesion, disaster preparedness, and risk reduction (S. Cutter, 2016; Saja et al., 2018, 2019).

- ▪

- Process – Process indicators typically capture dynamic and ongoing aspects of a phenomenon. They focus on the activities, behaviors, or steps involved in a process, intervention, or program. They are valuable for assessing whether participants actively engage with and respond to an intervention. Examples may include the level of engagement, the frequency of communication, and a feeling of belonging to a community (S. Cutter, 2016; Saja et al., 2018, 2019).

- ▪

- Normative - shared beliefs, principles, and standards that guide the behavior of interactions of individuals in a community (Saja et al., 2019).

3.1.3. Summary

3.2. Key Resilience Frameworks

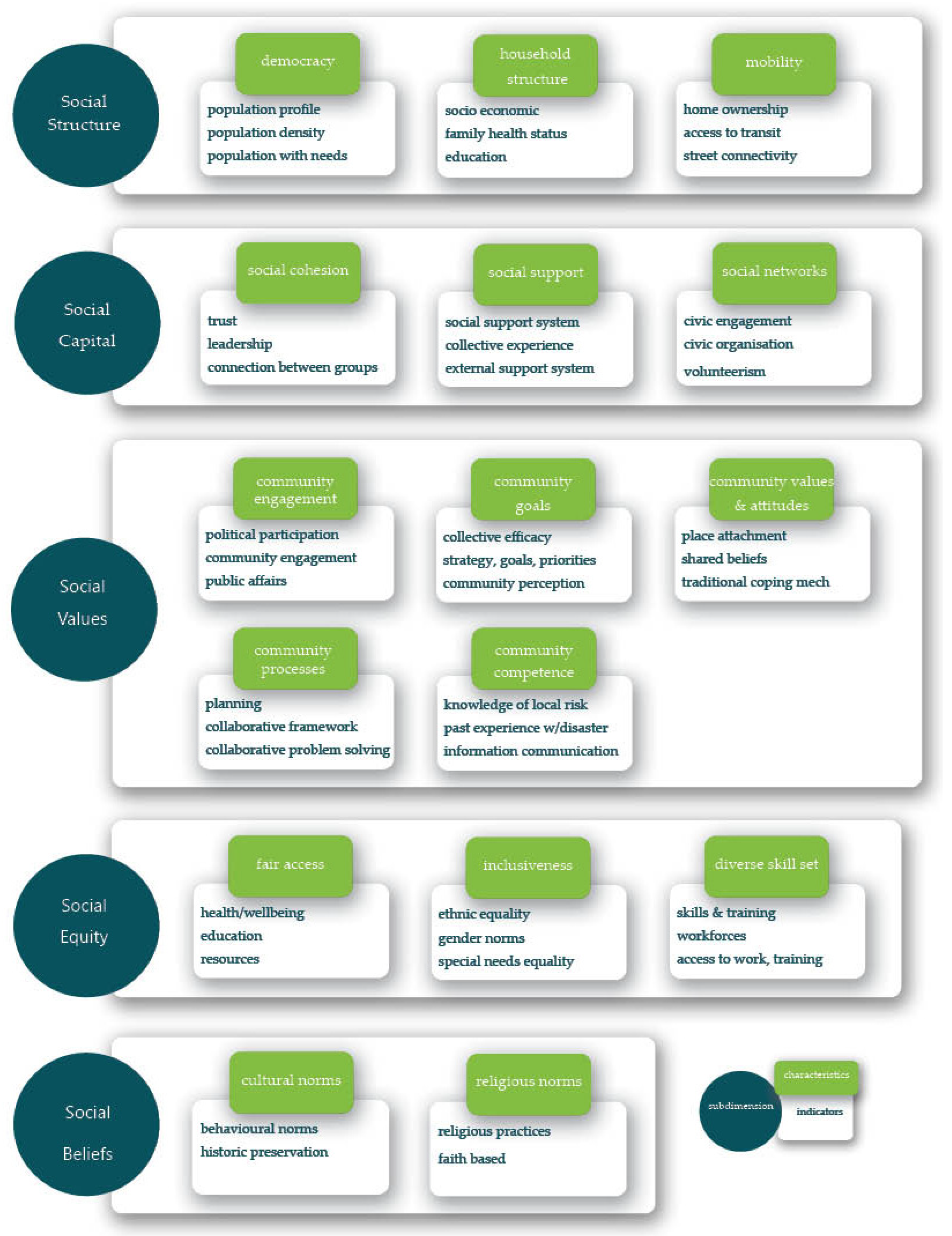

3.2.1. Inclusive & Adaptive 5S Framework

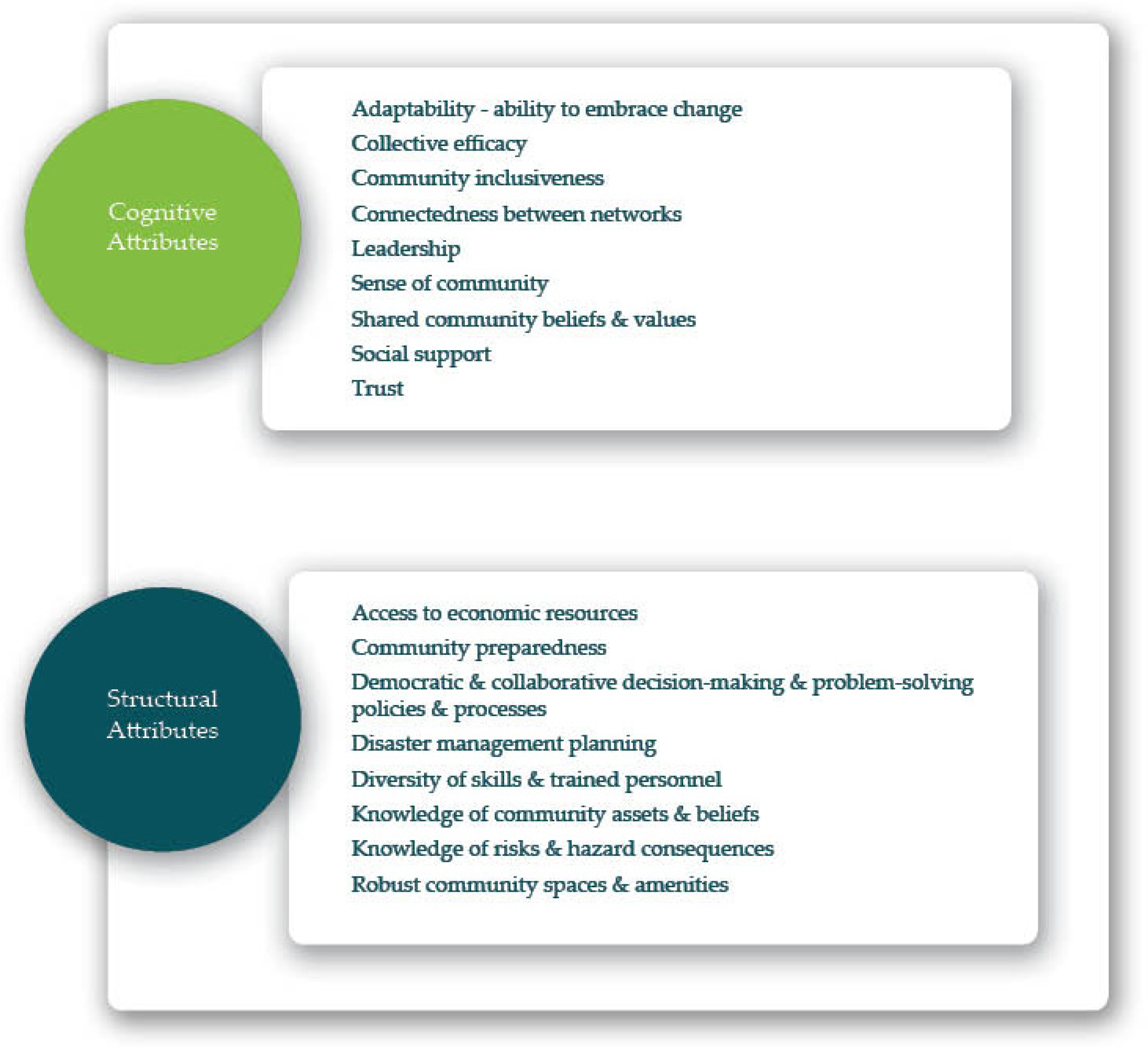

3.2.2. Practitioner Perspectives from Aotearoa New Zealand

3.3. Selection of Characteristics & Indicators for the BGI Context

3.3.1. Social Values & Beliefs

3.3.2. Social Capital

3.3.3. Social Structure

3.3.4. Social Equity

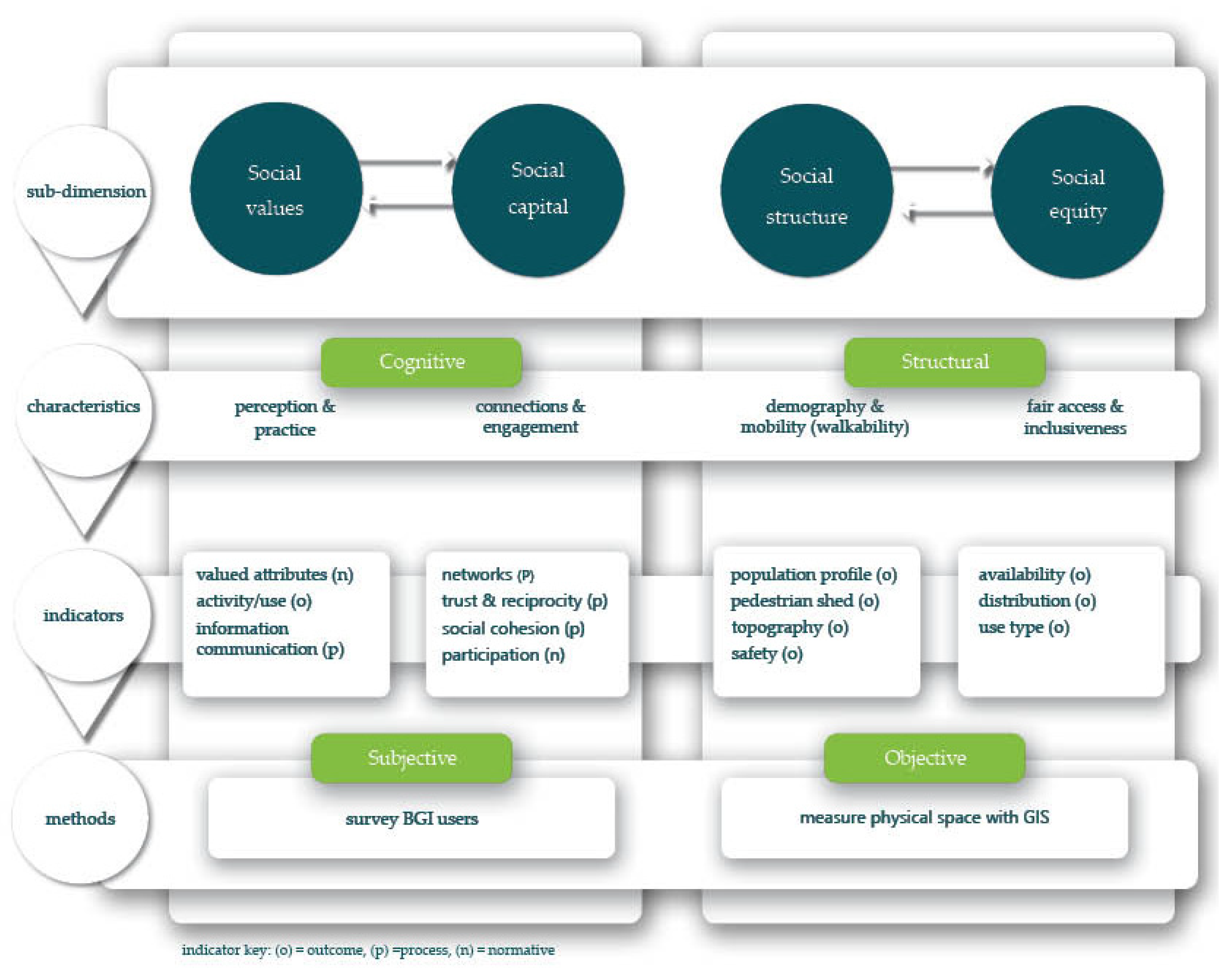

4.1. BGI Social Resilience Framework

4.2.1. Synthesizing Concepts, Application Context, and Measurement Type

- Conceptualization

- Application

- Measurement Type

4.2.2. Integrating Tools and Insights through Methodologies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Muntasir. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social Capital, Collective Action, and Adaptation to Climate Change. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 79, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Barnett, J.; Brown, K.; Marshall, N.; O’Brien, K. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Administrator, P.C.E. (2023, March 20). Aotearoa’s cities are losing their leaves. ArcGIS StoryMaps. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e3f4c7a2f8534d4e877d140ec209514c.

- Alberti, M.; Marzluff, J.M.; Schulenberger, E.; Bradley, G.; Ryan, C.; Zumbrunnen, C. Integrating Humans into Ecology: Opportunities and Challenges for Studying Urban Ecosystems. BioScience 2003, 53, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P. Fixing Recovery: Social Capital in Post-Crisis Resilience. Journal of Homeland Security, Forthcoming. 2010.

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social capital and community resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social Capital and Community Resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsheri, S.A.; Rezgui, Y.; Li, H. Delphi-based consensus study into framework of community resilience to disaster. Nat. Hazards 2015, 75, 2221–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschuler, A.; Somkin, C.P. Local services and amenities, neighborhood social captital, and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrey, C.L. Urban greenspace, physical activity and wellbeing: The moderating role of perceptions of neighbourhood affability and incivility. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbon, P. Developing a model and tool to measure community disaster resilience. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2014, 29, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, D.; Bene, C.; Charles, A.T.; Johnson, D.; Allison, E.H. The Interplay of Well-being and Resilience in Applying a Social-Ecological Perspective. Ecology and Society 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J. Adapting to climate change in Pacific Island countries: The problem of uncertainty. World Dev. 2001, 29, 977–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatley, T.; Newman, P. Biophilic Cities Are Sustainable, Resilient Cities. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3328–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Phoenix, C.; Lovell, R.; Wheeler, B.W. Green space, health and wellbeing: Making space for individual agency. Health Place 2014, 30, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.; Newman, G.; Lee, J.; Combs, T. Evaluation of Networks of Plans and Vulnerability to Hazards and Climate Change: A Resilience Scorecard. Journ Am. Plan. Assoc. 2015, 81, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L.; Welsh, J.A. Social capital and health in Australia: An overview from the household, income and labour dynamics in Australia survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, B.; Kurtz, L. Race, class, ethnicty, and disaster vulnerabilty. In Handbook of disaster research; 2018; pp. 181–203.

- Boyd, E.; Riyanti, D.; Gemenne, F. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Chapter 8 Poverty, livelihoods and sustainable development. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2022.

- Braveman, P.; Arkin, E.; Orleans, T.; Proctor, D. What is Health Equity? And what difference does it make? 2017.

- Broeder, L. den, South, J.; Rothoff, A. Community engagement in deprived neighbourhoods during the COVID-19 crisis: Perspectives for more resilient and healthier communities. Health Promotion International 2022, 37.

- Brown, H.I. Perception, theory, and commitment: The new philosophy of science. University of Chicago Press. 1979.

- Burton, C. A validation of metrics for community resilience to natural hazards and disasters using the recovery from Hurricane Katrina as a case study. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2015, 105, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.K.; Wisen, A. Restorative Commons: Creating Health and Well-Being through Urban Landscapes (Volume 39). Government Printing Office. 2009.

- Cecchini, M.; Cividino, S.; Turco, R. Population Age Structure, Complex Socio-Demographic Systems and Resilience Potential: A Spatio-Temporal, Evenness-Based Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamlee-Wright, E.; Storr, V.H. There’s no place like New Orleans”: Sense of place and community recovery in the Ninth Ward after Hurricane Katrina. J. Urban Aff. 2009, 31, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Williams, M.; Plough, A.; Stayton, A.; Wells, K.; Horta, M. GettingActionableAboutCommunityResilience:TheLosAngeles CountyCommunityDisasterResilienceProject. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, S.; Comes, T.; Bach, S.; Nagenborg, M.; Shulte, Y. Measuring social resilience: Trade-offs, challenges and opportunities for indicator models in transforming societies. Int. J. Diaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.S.; Perry, K.-M.E. Like a Fish Out of Water: Reconsidering Disaster Recovery and the Role of Place and Social Capital in Community Disaster Resilience. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 48, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, W.; Hamilton, T. Just green enough: Contesting environmental gentrificaiton in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Local Environ. 2012, 17, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S. The landscape of disaster resilience indicators in the USA. Nat. Hazards 2016, 80, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.; Ash, K.D.; Emrich, C.T. The geographies of community disaster resilience. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 29, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Derakhshan, S. Temporal and spatial change in disaster resilience in US counties, 2010–2015. Environmental Hazards and Resilence 2021, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cutts, B.B.; Darby, K.J.; Boone, C.G.; Brewis, A. City structure, obesity, and environmental justice: An integrated analysis of physical and social barriers to walkable streets and park access. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dade, M.C.; Mitchell, M.G.E.; Brown, G.; Rhodes, J. The effects of urban greenspace characteristics and socio-demographics vary among cultural ecosystem services. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haas, W.; Hassink, J.; Stuiver, M. The Role of Urban Green Space in Promoting Inclusion: Experiences From the Netherlands. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, A. Justince and the environment:Conceptions of environmenal Sustainabilty and theories of distributive justice. Claredon Press. 1998.

- Dreiseitl, H.; Wanshura, B. Strengthening Blue-Green Infrastructure In Our Cities. Ramboll. 2016.

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagg, J.; Curtis, S.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Cattell, V.; Tupuola, A.-M.; Arephin, M. Area social fragmentation, social support for individuals and psychosocial health in young adults: Evidence from a national survey in England. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, A.; Ghorbani, A.; Herder, P. Commoning toward urban resilience: The role of trust, social cohesion, and involvement in a simulated urban commons setting. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 45, 142–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fongar, Aamodt, Randrup, & Solfjeld. Does Perceived Green Space Quality Matter? Linking Norwegian Adult Perspectives on Perceived Quality to Motivation and Frequency of Visits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, R.; Kearns, A. Social Cohesion, Social Capital, and the Neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A. What is a walkable place? The walkability debate in urban design. Urban Des. Int. 2015, 20, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.A.; Pitner, R.; Freedman, D.A.; Bell, B.A.; Shaw, T.C. Spatial Dimensions of Social Capital. City Community 2015, 14, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, Lowe, & Winkleman. The value of green infrastructure for urban climate adaptation. Cent. Clean Air Policy 2011, 750, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J.; Giles-Corti, B.; Wood, L.; Knuiman, M. Creating sense of community: The role of public space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M.; Cashdan, L.; Paxson, L. Community open spaces: Greening neighborhoods through community action and land conservation. Island Press. 1984.

- Gardner, J. The inclusive healthy places framework: A new tool for social resilence and public infrastructure. Biophilic Cities J. 2019, 2, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for people. Island Press. 2013.

- Ghofrani, Z.; Sposito, V.; Faggian, R. A Comprehensive Review of Blue-Green Infrastructure Concepts. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H.; Westphal, L.M. The human dimensions of urban greenways: Planning for recreation and related experiences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagno, L. Human mobility in the Sendai Framework. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2016, 7, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H. Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Island Press. 2001.

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.L.; Maurer, K. Unravelling social capital: Disentangling a concept for social work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2011, 42, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckert, M. Access and Equity in Greenspace Provision: A Comparison of Methods to Assess the Impacts of Greening Vacant Land: Access and Equity in Greenspace Provision. Trans. GIS 2013, 17, 808–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heynen, N.; Perkins, H.A.; Roy, P. The political ecology of uneven urban green space: The impact of political economy on race and ethnicity in producing environmental inequality in Milwaukee. Urban Aff. Rev. 2006, 42, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.F.; Cleland, C.; Cleary, A.; Droomers, M. Environmental, health, wellbeing, social and equity effects of urban green space interventions: A meta-narrative evidence synthesis. Environ. Int. 2019, 130, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyyppä, M.T. Healthy Ties. Springer Netherlands. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A.J.; Vanclay, F. Using social impact assessment to strengthen community resilience in sustainable rural development in mountain areas. Mt. Res. Dev. 2016, 36, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Hamilton, C. Planning for Climate Change: A strategic, values-based approach for urban Planners (CITIES AND CLIMATE CHANGE INITIATIVE Tool Series). United Nations Human Settlements Programme (un-habitat). 2014.

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewett, R.L.; Mah, S.M.; Howell, N.; Larsen, M.M. Social Cohesion and Community Resilience During COVID-19 and Pandemics: A Rapid Scoping Review to Inform the United Nations Research Roadmap for COVID-19 Recovery. Int. J. Health Serv. 2021, 51, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joerin, J.; Shaw, R.; Takeuchi, Y.; Krishnamurthy, R. The adoption of a Climate Disaster Resilience Index in Chennai, India. Diasters 2014, 38, 540–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.P.; Lenartowicz, T.; Aqud, S. Cross-cultural competence in international business: Toward a definition and a model. J. Int. Busienss Stud. 2006, 37, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Tanner, T. Subjective resilience: Using perceptions to quantify household resleince to climate extremes and disasters. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurjonas, M.; Seekamp, E. Rural coastal community resilience: Assessing a framework in easteer North Carolina. Ocean & Coastal Managemetn 2018, 137–150.

- 7Kabisch, N.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; Bonn, A. (Eds.). Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice. Springer International Publishing. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Keck, M.; Sakdapolrak, P. What is social resilience? Lessons learned and ways forward. Erdkunde 2013, 67, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimic, K.; Ostrysz, K. Assessment of Blue and Green Infrastructure Solutions in Shaping Urban Public Spaces—Spatial and Functional, Environmental, and Social Aspects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KI-Moon, B. International Strategy for Disaster Reduction Summary Annual Report and Financial Statement [Annual Report]. United Nations. 2010.

- Kondo, M.; Fluehr, J.; McKeon, T.; Branas, C. Urban Green Space and Its Impact on Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnendijk, C.C. Evidence-based guidelines for greener, healthier, more resilient neighbourhoods: Introducing the 3–30–300 rule. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahn, G.L.; Walker, D.K.; Correa-De-Araujo, R. Persons With Disabilities as an Unrecognized Health Disparity Population. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, S198–S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, M.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Sachdeva, S.; Lee, K.; Westphal, L. Might School Performance Grow on Trees? Examining the Link Between “Greenness” and Academic Achievement in Urban, High-Poverty Schools. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, A.H. What is ‘social resilience’? Perspectives of disaster researchers, emergency management practitioners, and policymakers in New Zealand. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, A.H.; Doyle, E.E.H.; Becker, J.; Johnston, D.; Paton, D. What is ‘social resilience’? Perspectives of disaster researchers, emergency management practitioners, and policymakers in New Zealand. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamond, J.; Evertt, G. Sustainable Blue-Green Infrastructure: A social practice approach to understanding community preferences and stewardship. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.; Schöpfer, E.; Hölbling, D. Quantifying and Qualifying Urban Green by Integrating Remote Sensing, GIS, and Social Science Methods. In Use of Landscape Sciences for the Assessment of Environmental Security. Springer International Publishing. 2020.

- Lee, Y.-C.; Kim, K.-H. Attitudes of Citizens towards Urban Parks and Green Spaces for Urban Sustainability: The Case of Gyeongsan City, Republic of Korea. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8240–8254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.M. Climate Change and Urban Resilience. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.-H.; Malone-Lee, L.-C. (Eds.). Building Resilient Neighbourhoods in Singapore: The Convergence of Policies, Research and Practice. Springer Singapore. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Newman, G.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, R.; Horney, J. Coping with post-hurricane mental distress: The role of neighborhood green space. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 281, 114084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.Y.H.; Jim, C.Y. Citizen attitude and expectation towards greenspace provision in compact urban milieu. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M. Integration of natural area values: Conceptual foundations and methodological approaches. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 2005, 12(sup1), 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, B.; Kennedy, C.; McPhearson, T. Parksare Critical Urban Infrastructure: Perception and Use of Urban Green Spaces in NYC During COVID-19 [Preprint]. SOCIAL SCIENCES. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Nature deficit. Orion 2005, 70, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, C. Place systems and social resilience: A framework for understanding place in social adaptation, resilience, and transformation. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, A.; Wellman, B. Soail network analysis: An introduction. In The SAGE handbook of social network analysis; 2011; pp. 11–25.

- Maseda, M.; Neira, I.; Jimenez. Social Capital and Subjective Wellbeing in Europe: A New Approach on Social Capital. Social Indicators Research. 2012.

- Masuda, N. Disaster refuge and relief urban park system in Japan. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2014, 2, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, V.; Longman, J.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Braddon, M.; Passey, M.; Bailie, R.S.; Berry, H.L. Belonging and Inclusivity Make a Resilient Future for All: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Post-Flood Social Capital in a Diverse Australian Rural Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayunga, J. Understanding and applying the concept of community disaster resilience: A capital-based approach. Summer Acad. Soc. Vulnerability Resil. Build. 2007, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. 1986, 14, 6–23.

- Meerow, S. The politics of multifunctional green infrastructure planning in New York City. Cities 2020, 100, 102621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meheta, V.; Mahato, B. Designing urban parks for inclusion, equity, and diversity. J. Urban. 2021, 14, 457–489. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Opportunities and Challenges for Business and Industry [Assessment]. World Resources Institute. 2005. http://www. millenniumassessment.org/en/index.aspx.

- Miller, S. Greenspace volunteering post-disaster: Exploration of themes in motivation, barriers, and benefits from post-hurricane park and garden volunteers. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 2004–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh Pham, T.; Kondor, I.; Hanel, R.; Thurner, S. The effect of social balance on social fragmentation. J. R. Soc. Interface 2020, 17, 20200752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayedi, F.; Zakaria, & Bigah. Conceptualising the indicators of walkability for sustainable transportation. J. Technol. 2013, 65, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Libertati, A.; Tetzlaff, J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R.; Wesener, A.; Davies, F. Bottom-up governance after a natural disaster: A temporary post-earthquake community garden in Central Christchurch, New Zealand. NA 2017, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, B.H. Morrow, B.H. Community resilience: A social justice perspective [4]. 2008.

- Moseley, D.; Marzano, M.; Chetcuti, J.; Watts, K. Green networks for people: Application of a functional approach to support the planning and management of greenspace. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 116, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Takara, K. Urban green space as a countermeasure to increasing urban risk and the UGS-3CC resilience framework. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadel, S.F. The theory of social structure; 2013; Vol. 8.

- Nakagawa, Y.; Shaw, R. Social capital: A missing link to disaster recovery. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disasters 2004, 22, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, S.; Arthur, S. Influence of Blue-Green and Grey Infrastructure Combinations on Natural and Human-Derived Capital in Urban Drainage Planning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, K.F.; Wyche, R.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutsford, D.; Pearson, A.L.; Kingham, S. An ecological study investigating the association between access to urban green space and mental health. Public Health 2013, 127, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutsford, D.; Pearson, A.L.; Kingham, S.; Reitsma, F. Residential exposure to visible blue space (but not green space) associated with lower psychological distress in a capital city. Health Place 2016, 39, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrist, B.; Pfeiffer, C.; Henley, R. Multi-layered social resilience: A new approach in mitigation research. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2010, 10, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode Sang, Å.; Knez, I.; Gunnarsson, B.; Hedblom, M. The effects of naturalness, gender, and age on how urban green space is perceived and used. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 18, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, E.; Netusil, N.; Chan, F.; Dolman, N.; Gosling, S. International Perceptions of Urban Blue-Green Infrastructure: A Comparison across Four Cities. Water 2021, 13, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’sullivan, R.; Burns, A.; Leavy, G.; Leroi, I. Impact of the COVID 19 pandemic on lonliness and social isolation: A multi-country study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallathadka, A.; Pallathadka, L.; Rao, S.; Chang, H.; Van Dommelen, D. Using GIS-based spatial analysis to determine urban greenspace accessibility for different racial groups in the backdrop of COVID-19: A case study of four US cities. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 4879–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamukcu-Albers, P.; Ugolini, F.; La Rosa, D.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Azevedo, J.C.; Wu, J. Building green infrastructure to enhance urban resilience to climate change and pandemics. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 36, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, M.; Thoms, M.; Flotemersch, J.; Reid, M. Monitoring the resilience of rivers as social-ecological systems: A paradigm shift for river assessment in the twenty-first century. River Science: Research and Managemetn for the 21st Century 2016, 197–220.

- Paton, D. Disaster resilience: Building capacity to co-exist with natural hazards and their consequences. In Disaster resilience: An integrated approach; 2006; pp. 3–10.

- Pelling, M.; High, C. Understanding adaptation: What can social capital offer assessments of adaptive capacity? Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Van Horn, R.L.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. A Conceptual Framework to Enhance Community Resilience Using Social Capital. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2017, 45, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, R.L.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Van Horn, R.L.; Norris, F.H.; Reissman, D.B. The communities advancing resilience toolkit (CART. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2013, 19, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, A.; Khan, A.Z.; Canters. Use-Related and Socio-Demographic Variations in Urban Green Space Preferences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Dawley, S.; Tomaney, J. Resilience, Adaptation and Adaptability. Cambridge Journal of Regions 2010, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects. World Urbanization Prospects. 2018. https://population.un.org/wup/.

- Prior, T.; Hagmann, J. Measuring resilience: Methodological and political challenges of a trend security concept. J. Risk Res. 2014, 17, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect 1993, 4(13 Spring).

- Putnam, R. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and schuster. 2000.

- Ramsey, I.; Stennkamp, M.; Thompson, A. Assessing community disaster reilience using a balanced scorecard: Lessons learnt from three Australian communities. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2016, 31, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, P.J.G.; Goncalves, L.A.P.J. Urban resilience: A conceptual framework. Sustain. Cities 2019, 50, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.; Pearce, J.; Mitchell, R.; Day, P.; Kingham, S. RTehseaerchaasrtsicole ciation between green space and cause-specific mortality in urban New Zealand: An ecological analysis of green space utility. 2010.

- Rigolon, A. A complex landscape of inequity in access to urban parks: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 153, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A. Parks and young people: An environmental justice study of park proximity, acreage, and quality in Denver, Colorado. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Gibson, S. The role of non-government organisations achieving environmental justic for green and blue spaces. Landscdapeand Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Yanez, E.; Aboelata. “A park is not just a park”: Toward counter-narratives to advance equitable green space policy in the United States. Cities 2022, 128, 103792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Thompson, C.; Aspinall, P.; Brewer, M.; Duff, E.; Miller, D.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A. Green Space and Stress: Evidence from Cortisol Measures in Deprived Urban Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4086–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, A. Defining and measuring economic resilience to disasters. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2004, 13, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Krull, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022. Cambridge University Press. 2022.

- Saja, A.M.A.; Goonetilleke, A.; Teo, M.; Ziyath. A critical review of social resilience frameworks in disaster management. Int. J. Disater Risk Reduct. 2019, 35, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saja, A.M.A.; Teo, M.; Goonetilleke, A.; Ziyath, A.M. An inclusive and adaptive framework for measuring social resilience to disasters. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, R.; Yok, T.P.; Chua, V. Social capital formation in high density urban environments: Perceived attributes of neighborhood green space shape social capital more directly than physical ones. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 227, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalenghe, R.; Marson, F.A. The anthropogenic sealing of soils in urban areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefer, D.; van der Noll, J. The Essentials of Social Cohesion: A Literature Review. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, M.; Le Texier, M.; Caruso, G. Spatial sorting, attitudes and the use of green space in Brussels. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch-Spana, M.; Gill, K.; Hosangadi, D.; Slemp, C.; Burhans, R.; Zeis, J.; Carbone, E.G.; Links, J. The COPEWELL Rubric: A Self-Assessment Toolkit to Strengthen Community Resilience to Disasters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempier, T.T.; Swan, D.L.; Emmer, S.H.; Schneider, M. Coastal community resilience index: A community self-assessment, online. 2010.

- Seymour, E.; Curtis, A.; Pannell, D.; Allan, C.; Roberts, A. Understanding the role of assigned values in natural resource management. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. A critical review of selected tools for assessing community resilience. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 69, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Yamagata, Y. Urban resilience assessment: Multiple dimensions, criteria, and indicators. Urban Resilience: A Transformative Approach 2016, 259–276.

- Shiva, V. Earth democracy: Justice, sustainability and peace. Zed Books. 2006.

- Surjono, A.Y.; Setyono, D.A.; Putri, J. Contribution of Community Resilience to City’s Livability within the Framework of Sustainable Development. Journal of Environmental Research 2021, 77, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, E. Cultivating resilience: Urban stewardship as a means to improving health and well-being. In Restorative commons: Creating health and well-being through urban landscapes. Gen. Tech Rep. NRS-P-39. US Department of Agriculture; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. 2009; pp. 58–87.

- Svendsen, E.; Campbell, L.K. Land-markings: 12 journeys through 9/11 living memorials (49). US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 2006.

- Tidball, K.G.; Krasny, M.E.; Svendsen, E.; Campbell, L.; Helphand, K. Stewardship, learning, and memory in disaster resilience. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigg, J. Disaster risk reduction. Overseas Development Institute, Humanitarian Policy Group. 2015.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. The Sustainable Development Goals: Report 2022. 2022.

- Urquiza, A.; Amigo, C.; Billi, M.; Calvo, R. An Integrated Framework to Streamline Resilience in the Context of Urban Climate Risk Assessment. Earth’s Future 2021, 9.9.

- Van Riper, C.J.; Sharp, R.; Bagstad, K.J.; Vagias, W.M.; Kwenye, J.; Depper, G.; Freimund, W. Recreation, Values, and Stewardship: Rethinking Why People Engage in Environmental Behaviors in Parks and Protected Areas:Chapter 19. 2016; pp. 117–122.

- Vaske, J.J.; Donnelly, M.P. A Value–Attitude–Behavior Model Predicting Wildland Preservation Voting Intentions. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1999, 12, 523–537. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, E.M.; Speight, S.L. Multicultural competence, social justice, and counseling psychology: Expanding our roles. Couns. Psychol. 2003, 31, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Albert, C.; Von Haaren, C. The elderly in green spaces: Exploring requirements and preferences concerning nature-based recreation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Wheeler, B.W.; Depledge, M.H. Would You Be Happier Living in a Greener Urban Area? A Fixed-Effects Analysis of Panel Data. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.G.; Logan, T.M.; Zuo, C.T.; Liberman, K.D.; Guikema, S.D. Parks and safety: A comparative study of green space access and inequity in five US cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 201, 103841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough. ’ Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Rush, J.; Bailey, F.; Just, A.C. Accessible Green Spaces? Spatial Disparities in Residential Green Space among People with Disabilities in the United States. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2023, 113, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, B.; Gooden, S. The epic of social equity: Evolution, essence, and emergence. Adm. Theory Prax. 2009, 31, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Urban green space interventions and health: A review of impacts and effectiveness. 2017.

- Yoon, D.K.; Kang, J.E.; Brody, S. A measurement of community disaster resilience in Korea. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, W.; Zeng, C.; Gao, L.; Li, M.; Peng, C. Accessibility measurements for urban parks considering age-grouped walkers’ sectorial travel behavior and built environment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 76, 127715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga-Teran, A.; Gerlak, A. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Analyzing Questions of Justice Issues in Urban Greenspace. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Description | Framework References |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptualization | Structural & cognitive | Encompasses (structural) discrete features and characteristics of a social entity and (cognitive) attitudes, values, and beliefs | (Kwok, 2016; Saja et al., 2018) |

| Coping, adaptive, transformation | Capacities of communities to cope adapt, and transform to dynamic challenges; embracing change, and fostering long-term sustainability and growth. | (Lyon, 2014; Parsons et al., 2016) | |

| Social & interconnected | Web of relationships & networks within a community, underscoring the role of social ties, collective action, and the integration of diverse community Resources in building resilience. | (S. Cutter et al., 2008; Saja et al., 2018; Sempier et al., 2010) | |

| Capital based | resilience in terms of capital and strategic deployment of resources as essential | (S. L. Cutter & Derakhshan, 2021; Mayunga, 2007; Yoon et al., 2016) | |

| Context | Hazard specific | e.g. earthquake, flood, drought, sea level rise | (Burton, 2015; Jurjonas & Seekamp, 2018) |

| Geographical context | urban, coastal, rural, city, mountains, islands | (Chandra et al., 2013; Imperiale & Vanclay, 2016; Jurjonas & Seekamp, 2018; Ribeiro & Goncalves, 2019) | |

| Hierarchical scale | Individual, community, governmental | (B. Pfefferbaum et al., 2017; Saja et al., 2019) | |

| Assessment type | Indicator | Observable measurable characteristic/change representing resilience characteristic | (Burton, 2015; Kwok, 2016; Mayunga, 2007; Saja et al., 2018; Sharifi & Yamagata, 2016; Yoon et al., 2016) |

| Scorecard | Aggregate of score based on how often the items are present, often providing evaluation of progress to goal. | (Berke et al., 2015; Ramsey et al., 2016) | |

| Toolkit | Guidance through sample procedures, survey ins(R. L. Pfefferbaum et al., 2013; Schoch-Spana et al., 2019) | (Arbon, 2014; R. L. Pfefferbaum et al., 2013; Schoch-Spana et al., 2019) | |

| Indicator type | Outcome | How well interventions accomplish a result | (Burton, 2015; S. Cutter, 2016; Kwok, 2016; Saja et al., 2019; Sharifi & Yamagata, 2016) |

| Process | Level of engagement in phenomenon | (Burton, 2015; S. Cutter, 2016; Kwok, 2016; Saja et al., 2019; Sharifi & Yamagata, 2016) | |

| Normative | Shared beliefs & values guiding behaviour | (Copeland et al., 2020; Kwok, 2016) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).