Background

All eligible Japanese citizens 65 and older who qualify now have access to long-term care insurance (LTCI) according to a national law the Japanese government passed in April 2000. [

1] As a developed country, Japan faces an increasingly severe ageing problem. Japan's ageing population is even more serious, reaching 2.84 billion in 2022. [

2] Therefore, the demand for LTCI in Japan has increased significantly since the impact of COVID-19 on older adults has intensified recently, and the cost of care has caused a severe financial burden on older adults and their families. [

3] In this situation, before 2025, the cost of long-term care insurance (LTCI) is projected to increase from

$100 billion to

$210 billion. High-standard social care services based on need and geography, Japan developed the LTCI system in 2000 to enhance older freedom and to choose suitable. [

4]

The government of Japan is compelled to expand beyond the restricted public guidance LTC service supply, which low-income seniors increasingly employ due to a historically extraordinary ageing population. [

5] Consequently 2000, the public LTC Insurance Scheme (LTCI) was launched. These 16 "ageing-related" disorders, such as advanced cancer, cerebrovascular issues, osteoporosis, Parkinson’s Disease, etc., affect those 65 and older as well as those 40 and older. [

6] According to recent statistics, the LTCI had over 28.9 million participants who were 65 or older. [

7] About 3.9 million people use LTCI-covered services monthly, making up around one in six insured patients, or 4.6 million people. [

8]

Cost growth is one of the burdens in Japan regarding LTC. The following amounts are spent on services: 3.3 trillion yen for residential care, 0.6 trillion yen for care in the community, and 2.6 trillion yen for institutional care. [

9] At 1.8 per cent of GDP, it is estimated that LTC spending overall increased gradually from 2007 to 2025. By 2025, it is anticipated to increase to 309 billion USD, or about three times in 15 years. [

10]

Objectives

This paper aims to evaluate the effects of LTCI implementation in Japan, explore the economic and social impact, and make relevant policy recommendations.

It is crucial to differentiate between each reversible and irreversible multifunctional performance of older persons at various certification levels in preventing future functional decline in elderly persons and giving them appropriate care. To answer significant topics in the cross-sectional study, we evaluated and compared complete geriatric functioning among older persons living in the community at various quality of healthcare in the national LTCI system. This study's objective is to reevaluate the benefits and drawbacks of the LTCI system, considering the actual circumstances faced by older people living in Japan's rural, underpopulated, and ageing metropolitan regions.

Methods

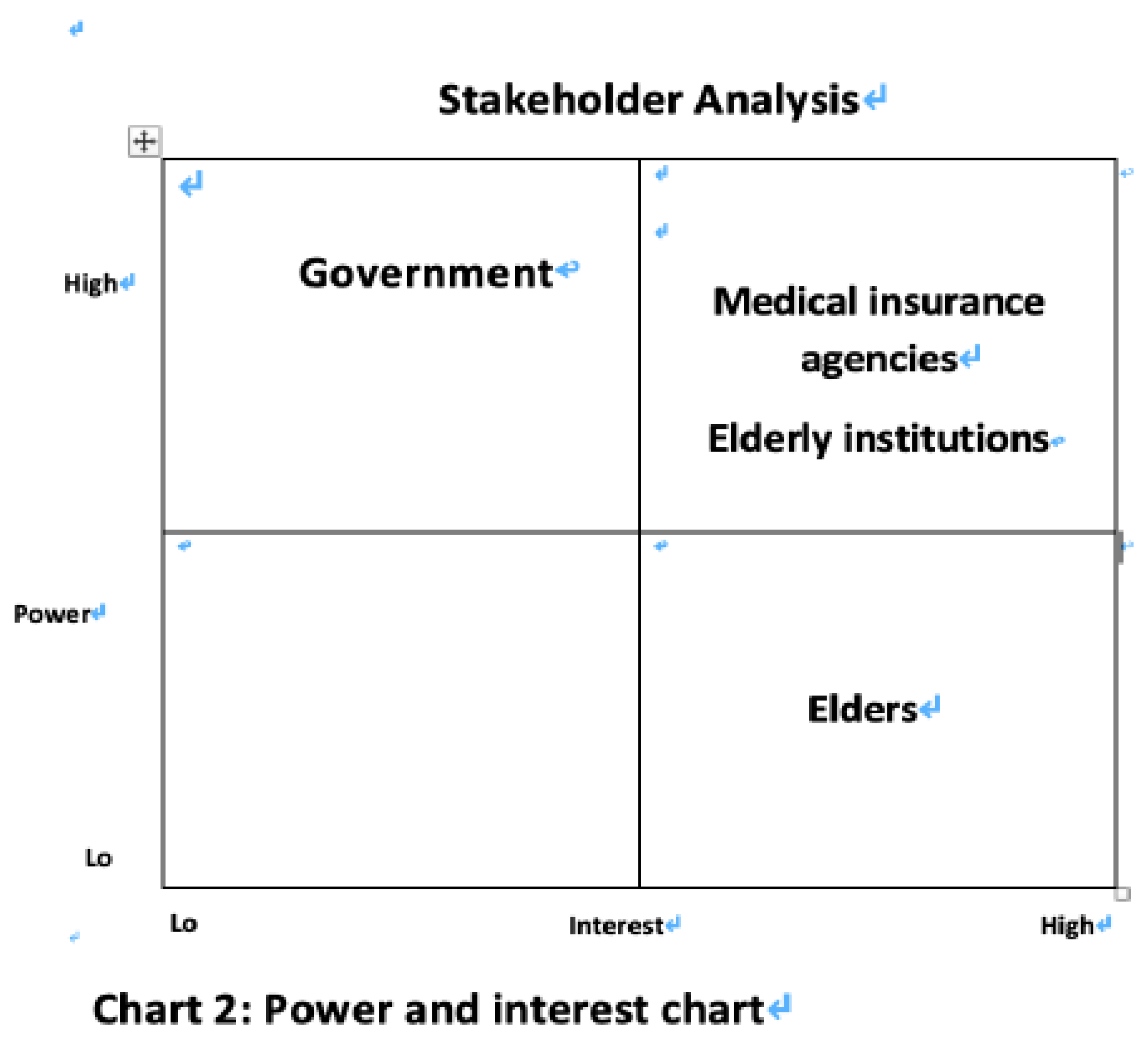

The overview of the report is divided into three parts. The first part is to conduct a stakeholder analysis to identify stakeholders and discuss their power and interest in establishing a coalition to enhance the sustainability of LTCI. Using the "power-interest" model to help make better policy decisions. [

11]

The second part involves the literature review method, which was conducted to compare the implementation approaches in Japan, and data were systematically collated to evaluate effects. Their characteristics were summarised to compare the impact of the policies on health equity and public health of older people in Japan.

The final part examines how the new medical insurance system would affect medical resources using supply-side and demand-side economic analyses. The link between supply and demand is the fundamental cornerstone of economics. This section addresses ways to balance supply and demand and the elements that influence supply and demand.

Part 1: Stakeholder Analysis

Stakeholder Analysis of the LTCI

This report analyses and evaluates four stakeholders: seniors, government, health care providers, and aged care facilities. The stakeholder analysis helps to enhance the impact of LTCI on different stakeholder groups and to integrate the resources of all stakeholders to develop strategies to assess the impact on older people more effectively.

An overview of the LTCI in Japan

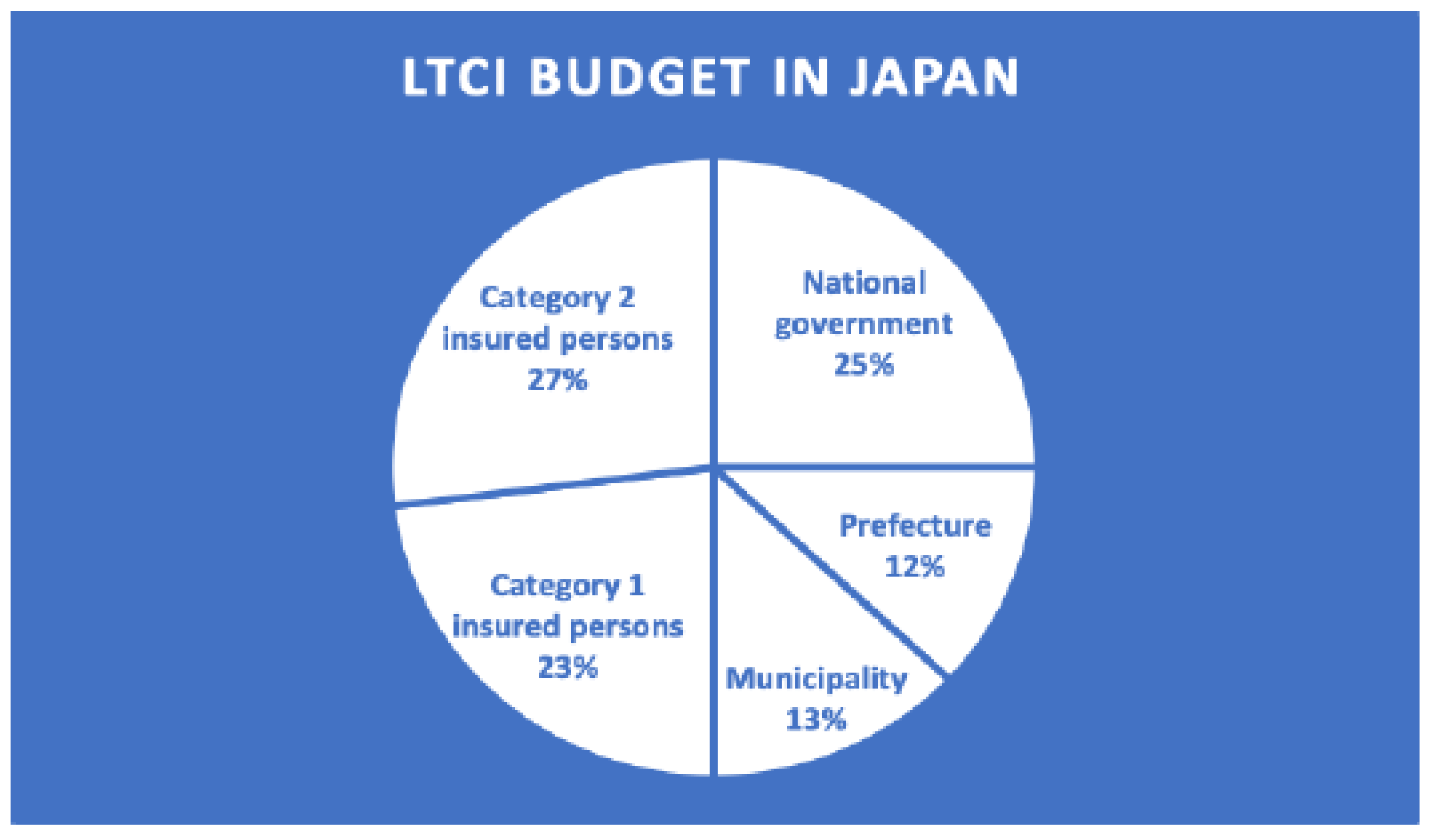

The LTCI budget for Japan comprises premiums of 50 per cent and taxes of 50 per cent. [

12] Every citizen 40 years of age and older must pay premiums under this system, funded by taxes levied by the national government (25%) and prefectures, which account for 12.5%, and municipalities, which occupy 12.5%. [

12] In the LTCI system in Japan, seniors who are approved for LTCI services make a 10% co-payment; the LTCI budget pays the remaining 90% of costs. [

13]

The city created t

he LTCI Service Plan and revised it every three years. [

3] The plan will determine how premiums and copays are changed. In 2000, when the LTCI system was first implemented, long-term care expenditures were 3.6 trillion yen (

$32.7 billion), but as the population ages, they have risen to

$106.4 billion in 2019. [

14] By 2025, the amount is anticipated to surpass

$136.4 billion. [

15] The cost of living has changed; premiums went from 2,911 yen in 2000 to 5,514 yen in 2015 [

16], and the copays for dependent older people with middle- and high-incomes (3.4 million yen or more) were increased to 20% or 30%. [

17] The Category 1 insured person refers to LTCI participants aged 65 and over, accounting for 23%, and those between the ages of 40-64 covered by long-term health insurance plans are called Category 2 insured persons, which occupied 27%.

The Stakeholders and Their Workflow

The government, as the policy implementer, issues policies and invests money and workforce to reach health facilities and communities, which are monitored and managed by the government, while older adults, as the most direct stakeholders, provide feedback information on their needs to the communities and health facilities and finally to the government. [

18]

Elderly People

Older people have a high interest as beneficiaries of insurance but a low power for LTCI, are susceptible to chronic diseases and have a higher rate of severe illness and mortality from infectious diseases such as SARS and COVID-19. Evidence suggests that the interests of people of low socio-economic status are often neglected, that these groups are primarily made up of older people and that they are more vulnerable to infectious diseases because of their poor resistance and poorly ventilated, densely populated living conditions. Some elderlies are also affected by their conditions, and some of them lack reliable financial resources, especially in the case of disabled people, who are unable to take care of themselves. As a result, the need for older people to be below LTCI increases over time.

Government

The government provides part of the funding for LTCI, and the government faces a substantial financial outlay and needs to work with health insurance providers. The Japanese government has been involved in developing home care services over the past two decades, and the government has provided various financial incentives for LTCI services, such as low-interest loans, subsidies, and relatively high tariff schemes. [

1] The government has more power as the developer and implementer of the LTCI system through subsidies and financial support and by working with insurance companies to secure additional funding. The government should also take an active and socially responsible role in providing the assistance that older people need.

Health insurance providers

Hospitals mainly provide long-term care services, and the influence of medical organisations is significant. Although the implementation of LTCI will increase the burden on healthcare institutions, The healthcare sector faces more urgency due to Japan's rapidly ageing population, which results in a sharp rise in the number of older adults seeking medical attention and some hospitals beginning to serve as nursing homes. LTC is independent of the Department of Health and Social Services; it will positively impact social health equity. Moreover, as the leading implementer of the policy, healthcare institutions need to ensure that they can provide timely and effective treatment to older adults.

Elderly institutions

Care institutions also play a vital role in implementing the system. They can be a good option for family members to care for older adults when they are under pressure. The three types of care include home care, community care and institutional care. Home care refers to the delivery of medical assistance in the patient's residence and significantly improves the health of LTCI recipients. In contrast to community care, in-home care provides one-on-one assistance at home. Most local seniors get LTC at home or in the familiar community. The number of institutions licensed by LTCI in Japan is 184392 (2012)[

19], and the turnover of staff in institutions is influenced by fluctuations in the price of care, with institutions as the primary caregivers, therefore gaining more power and interest.

Hospitals

Due to a lack of nursing homes and home care services, hospitals in Japan are frequently utilised for non-medical reasons, and patients are frequently kept in hospitals for extended periods. According to statistics, over 30% of senior patients have spent more than a year in the hospital as an alternative to long-term care facilities. [

20] Many private acute-care hospitals have bought or established long-term care facilities to increase administrative effectiveness. [

20]

Healthcare staff

The healthcare sector now faces more urgency due to Japan's rapidly ageing population, leading to a sharp increase in the percentage of older adults seeking medical attention and some hospitals beginning to serve as nursing homes. However, the government is now taking action, including home long-term care, which could relieve the strain on medical staff.

Adult population

The category two insured persons fall within the 40–64 age range, and their premiums are subtracted from the cost of medical insurance. [

21] The insurance funds are split equally between general taxes and insured premiums, with the remaining 50% coming from general taxes. [

21] Although the method used to determine premiums differs from fund to fund, it generally depends on the wealth and income of each household. By using this funding strategy, the financial burden of families could be kept reasonable, there will not be excessive financial strain, and the public LTCI system can continue to expand steadily and continuously.

Building alliances and partnerships

The government should actively promote alliances and partnerships with other interest groups to understand more about the influence of LTCI implementation on older people in Japan. Although the present LTCI program in Japan has mostly full terms of service, the government mainly controls the system, making other options, such as private long-term care insurance, frequently inaccessible in Japan. Therefore, older adults in Japan have no alternative but to count on the national LTCI program if they require long-term care.

Older people and their families should actively cooperate with the government and medical institutions in their care. The government should assist and increase the participation of older people. Japan should focus more on the sustainable development of LTCI as part of a mature care system.

In collaboration with health insurance institutions and professional care institutions, the government should provide good care for older adults and ensure the provision of daily living for older adults population. The government, in collaboration with health insurance institutions, should obtain financial support and expand the coverage of LTCI, and in collaboration with medical institutions, help to better relieve the mental stress and financial burden of older adults, i.e., the families behind them, by providing assistance services and better-promoting health equity.

Therefore, it is essential to build links between older people and the government and other stakeholders and to build alliances and partnerships to increase participation and enhance their power and interests. [

22]

Part 2: Evaluate policy for their impact.

Literature review

A literature review allows for experience and insight to be gained by examining different pieces of literature. The report reviews 20 pieces of literature, of which seven were analysed using quantitative analysis and 13 using qualitative analysis. Japan, as an Asian country, is strongly influenced by traditional core values that focus on health equity and health efficiency. Psychosocial factors also pray for more critical influences, particularly unmet needs for care services and self-image ratings, which significantly influence the choice of elderly at the undergraduate level and above. [

2]

Search Process

The primary databases considered were the Web of PubMed, Medline, SCOPUS, ProQuest, EMBASE, EBSCO and Science Core Collection. [

23] To increase the scope and kind of results found in the search, the Selected sample "and" was tested with the following word combinations: "LTCI" OR "Long Term Care Insurance".[

19]

Quality Appraisal

This paper utilised the “Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)”[

4] to assess each of the 20 papers that were chosen, and we chose four of the original 10 CASP Checklist questions that applied to our work to assess its quality. The results are displayed in

Table 1. [

21] The four questions are: (1)Was the paper's concentration on a particular issue? (2) Do you believe all pertinent, significant research was cited? (3) Can the local populace use the results? (4) Were all key outcomes taken into account? Each question had one of the following possible answers: Yes, No, N/A.

Table 1 displays the evaluation findings for all literature materials.

Results and Analysis

The benefits of implementing LTCI meet the need for LTC for older adults, especially those with disabilities, and relieve older adults of the financial burden caused by their payments. [

20] In Japan, LTCI has also helped reduce the loss of benefits for families of older people with disabilities. Additionally, it has enhanced the well-being and standard of living of seniors. [

24] In Japan, each older adult is assessed by a professional care manager (CM) who has received professional induction training and who assigns a level of care to the older adult based on their physical condition by using the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale. [

25] Older adults' cognitive capacity is evaluated to decide if they can utilise assistive technology and standards for home care, guiding, and administration. [

4]

Impact of LTCI on Health Equity

According to Saito et al. research,[

4] it is hypothesised that LTCI reduces income inequality caused by financial burden and, firstly, that LTCI regulation pilots need to be better linked to other social security schemes than the basic health insurance scheme in order to help reduce caregiver depression symptoms. [

4] The LTCI policy pilot significantly improved older people's general health concerning health outcomes, and the Theil index showed that older individuals in the treatment group had less disparity in inpatient and outpatient reimbursement costs. Inequalities in ADL impairment and self-rated health were smaller for older persons in the intervention group when compared to a control group on the Theil Index. [

26] The outcomes of the inequality measures imply that the policy has enhanced low-income individuals' income, decreased disparity in inpatient and outpatient requests, and decreased the concentration score for severe sickness and ADL handicaps. However, there are increasing disparities in severe disease. [

5]

Impact of Subsidy Policies on Equity

Not only have programs that provide subsidies been implemented in Japan to address long-term care for older adults, but it has also promoted health equity by facilitating the rational allocation of healthcare resources and putting insurance funds to good use. It has also been found through research that LTCI ease the financial burden on older adults and the families behind them, promote operational efficiency and better reflects the enhancement of health equity.

Impact of Public LTCI Compared with Different Countries

First, the influence of public LTCI on beneficiaries' health has improved significantly in Germany, the first country to create formal law and a public LTCI. Beneficiaries of the public LTCI program have considerably improved their physical health, particularly those receiving quality home care. [

31] The two Asian nations with the best public LTCI results between 2000 and 2008 were Japan and South Korea. [

10] Second, to build public LTCI sustainably, it is necessary to address the influence of LTCI on the financial stresses of recipient families. For example, by adopting the public LTCI, Germans' opinion of financial security improved with income. However, there were disparities based on gender and age, which is that women spend more money as they age than men do. [

22] When public LTCI was introduced in 2000, it assisted Japanese households in lowering welfare losses from disabled relatives. Although medical costs have gone up for older adults in Korea, LTCI recipients still have a much lower burden than non-beneficiaries. The labour market and long-term care providers will be affected by public LTCI third. Geyer, a German professor, created a structural model of the labour market and welfare options available to family care. [

1] He discovered that in-kind benefits did not affect the labour market. Japanese research found that introducing public LTCIs boosted family care engagement in the labour force, with different results depending on the caregivers' gender and age. Finally, the effects of the architecture of the LTC system are explored, including the care modalities. Public LTCI has a different impact on different long-term care alternatives depending on the nation, and it is limited by things such as income level, living circumstances, and other factors.

Part 3: Economics Analysis

Analysis of the Level of Demand for Healthcare in Japan

A review of the LTCI policy, implemented in 2000, is required every five years. The Japanese government amended the plan more than once in 2003 and then again in 2006, partly because expenditures were growing due to the increase of LTCI users. The reform's primary goal is to reduce costs by raising fees, cutting benefits, and encouraging independent living through preventative healthcare. A decrease in reimbursement for the utilisation of institutional care and an enhancement in reimbursement for home support and services, management of home care, and rehabilitation services to support living at home were among the changes made in 2003 due to the high demand for institutional care. [

1] A literature review found that demand is more influenced by factors such as price, age and income in Japan. The latest government data from the long-term care insurance (LTCI) system examines how insurance coverage affects long-term care usage and its consequences on health in Japan. [

27] There is a significant potential demand for the LTCI for disabled older adults in Japan and an urgent need for a system to defuse the financial risks associated with disability. Therefore, the contribution is projected using forecasts for the supply and demand balance for 2020 to 2050, which identify critical aspects of financing mechanisms and provide a basis for building a unified and sustainable system. [

32]

Features of Japan's Health Financing System

Only 10% of the overall cost of care is covered by Japanese insurance, with the other 90% being split between the government and premium payments. [

16] A certain amount is provided within which a certain level of care can be chosen, and the individual needs to bear any part above the fixed amount. This system facilitates the sustainable development of LTCI. Kobayashi et al. investigated how old patients' medical treatment was paid for in Japanese hospitals, nursing homes, and residences. [

1] The authors describe the structural alterations in the Japanese healthcare system. The LTCI has been in place for three years. The paper by Asahara et al.[

9] sought to outline the framework, current state, issues with the system, and the difficulties and potential role of LTCI going forward. The number of organisations offering LTCI services, as well as the number of institutions and consumers, has been rising significantly. [

28] Bayarsaikhan discusses the focus of health promotion policy, financing arrangements and the prospects for social health insurance to finance health promotion. [

29] Li et al., developing a long-term care insurance (LTCI) system. [

16] Yamada focuses on ascertaining differences in healthcare outcomes, such as different healthcare financing, and analysing disparities in health outcomes depending on income and education across various healthcare systems in China, Japan, and the United States. [

12] She also wants to document and describe decision preferences regarding preventive behaviours, such as preventing breast cancer through different health insurance frameworks. Due to its ageing population, Japan must figure out how to pay for long-term care, retirement, and healthcare costs. [

29] Using a dynamic equilibrium model with overlapping generations that is precisely parameterised to fit macro and microeconomic level data for Japan, McGrattan et al. examine the effects of policy decisions intended to solve this issue. [

33] Japan is struggling with how to pay for long-term care, retirement, and healthcare costs as the population ages. This study uses constant chi-square Markov methods and generalised linear models to depict the movement patterns of long-term health status changes using data from a multi-period micro-tracking survey. Additionally, it integrates information from all seven censuses with age-shifting algorithms to estimate the size and composition of older adults with disabilities from 2020 to 2040. [

30]

Impact of LTCI on Caregivers

LTCI positively impacts caregiver engagement and is also influenced by caregiving style. In Japan, caregivers are younger but have higher care satisfaction and are affected by gender and age differences. LTCI also helps seniors and families reduce the cost of care while improving the quality of care.

Impact of LTCI on Economic Well-Being

According to the healthcare requirement and certification evaluation, insured individuals qualified for supporting or care requirements may use LTCI services. Benefits are provided for in-home services such as home visits, daycare, and short-term nursing care. They are also provided for long-term care institutions, including long-term care welfare programs, long-term care hospitals, also known as geriatric facilities of medical services, and medical long-term healthcare nursing home residents. [

8] Family caregivers are not given cash assistance or other direct benefits. Care administrators are closely involved in treatment plans and service arrangements, and dependent older persons can pick and utilise the facilities, home care services, or community services offered by their care needs. Preventive care services are available to those not eligible for long-term or patient access. [

15] For Japan, this mainly addresses the financial pressures on families and the government and alleviates the oversupply of care services. It would be most desirable to increase co-payments rather than start contributions earlier over a more extended period. To reduce the future burden of LTCI, reduce the annual burden or shift the cost to a high public sector consumption tax.

Discussion

Influencing Factors Limiting the LTCI Development

In Japan, LTCI has experienced several modifications. Public care management organisations now prioritise younger subjects, male subjects, and those with more significant care requirements above private organisations. Beneficiaries managed by commercial organisations used society long-term care services far more frequently than those managed by public organisations. [

20] The importance of private care management companies in promoting the utilisation of care facilities cannot be overstated, even when the effectiveness of their care practices might well be questioned. [

22] Because LTCI payments in Japan only offer in-kind services, lower-income family care are less inclined to offer long-term care because they would instead get monetary benefits. [

31] Instead, the expense of official programs like LTCI and others may make it challenging to satisfy care needs with lower incomes, as seen in other nations. Low-income Japanese LTCI users are partially excused from out-of-pocket expenses. However, this exemption is only granted if the recipient requests it from the insurance provider. Due to a lack of knowledge or other reasons, some caregivers from these homes could choose not to apply for a waiver, which would limit access to complete LTCI services. [

34] Yamada et al. research also shows that care recipients who get public assistance are more inclined to work longer shifts as caregivers, even when coinsurance is waived in their case. [

12,

22] Therefore, the following study should thoroughly analyse the elements linked to increased care durations for these families. [

10,

16,

21]

Recommending Actions for the LTCI

One targets older adults with moderate care needs, and the government has pushed to create community care, which resembles a home and offers personal care facilities, respite care, and outpatient treatment facilities. There has been a surge in group homes in recent years, especially group homes that specifically provide accommodation for seniors with dementia. In 1998, there were only 41 collective dwellings. However, in 5 years, there have been 4,039 collective dwellings. [

32] By implementing new preventive care measures, these include family doctors, to decrease the number of clients needing a higher level of treatment and provide outpatient and short-term preventive care services. Since its implementation, the percentage of care preventive spending rose by 270 per cent between 2006 and 2009, far above the rates of institutional care (129 per cent), home care (180 per cent), and community care (138 per cent). The importance of outpatient rehabilitation is indeed recognised for its ability to preserve older individuals' health and well-being and to stop the decline in their health and functional abilities.

The second method is to modify the system to charge for services. Prior to the modification, recipients were not required to cover additional room and board expenses when utilising facility and temporary housing (also known as respite) services. [

35] However, changes made this different, and now the recipients are responsible for covering hotel expenses (i.e., board and lodging). [

35] Beneficiaries utilising day services will also be responsible for paying for meals. The justification for these modifications is that clients receiving assistance at home must pay out-of-pocket for housing maintenance and self-support. Therefore, recipients receiving institutional care pay for accommodation and board besides the care they get, which is done to encourage parity.

Finally, the government has established Region Integrated Support Centers to link these new LTC locations. The system envisioned in the proposal would provide a range of services at the minor district level or in each subdivision of a society of 20,000 to 30,000 people to address the various needs of seniors. [

36] Public health professionals, social services, and lead nurse managers construct nursing preventative care plans for potential LTC candidates. [

4] Creating a metric for ageing care demands that the local government follow a set method to determine the required care. Trained local government officials visited families to assess care needs using surveys on current psychological and physical health and medical treatments. After assessment, a government software program places every applicant in one of six dependent care categories. Finally, whether the initial level of nursing requirements is adequate is decided by the Nursing Needs Accreditation Committee, which consists of social and healthcare professionals nominated by the mayor. [

12]

Conclusion

LTCI has become an essential aspect of healthcare systems in ageing societies like Japan, but long-term care costs are rising. [

1] Thus, it is crucial to raise the standard of the integrated society health service and to continue to gather data on disability management in Japan to reduce the negative consequences of ageing, optimise the benefits and improve the health and longevity of older adults. [

10] The adoption of the LTCI system may not only lessen the financial burden on the families of those who receive and give medical care, as well as their anxiety and depression, but it can also help the medical services sector grow and the health and medical system's overall quality. Governments, however, must deal with two significant issues: first, how to cope with the significant fiscal expense associated with public LTCI; second, how to collaborate with other insurances, including pension insurance, to provide more social benefits.

In summary, tackling the challenges associated with LTCI in Japan requires a multifaceted approach that includes financial management, integration with other social support systems, quality enhancement in care provision, focused research, effective policy-making, and public education. Addressing these areas can help mitigate the effects of an ageing population on healthcare systems and improve the overall well-being of older adults. Future research should focus on LTCI-related issues in more depth, explain the effect mechanism, and identify the best treatment options.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the advisor for his support in writing this report and collecting the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Yong V, Saito Y. National Long-Term Care Insurance Policy in Japan a Decade after Implementation: Some Lessons for Aging Countries. Ageing international. 2011;37(3):271-84. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Zhang L, Xu X. Review of the evolution of the public long-term care insurance (LTCI) system in different countries: influence and challenge. BMC health services research. 2020;20(1):1057-. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka Y, Tamiya N, Kashiwagi M, Sato M, Okubo I. Comparison of public and private care management agencies under public long-term care insurance in Japan: A cross-sectional study. Geriatrics & gerontology international. 2010;10(1):48-55. [CrossRef]

- Saito T, Kondo N, Shiba K, Murata C, Kondo K. Income-based inequalities in caregiving time and depressive symptoms among older family caregivers under the Japanese long-term care insurance system: A cross-sectional analysis. PloS one. 2018;13(3):e0194919-e. [CrossRef]

- Kondo A. Impact of increased long-term care insurance payments on employment and wages in formal long-term care. Journal of the Japanese and international economies. 2019;53:101034. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi A, Ishibashi T, Shinozaki T, Yamamoto-Mitani N. Combinations of long-term care insurance services and associated factors in Japan: a classification tree model. BMC health services research. 2014;14(1):382-. [CrossRef]

- Lin H, Prince J. The impact of the partnership long-term care insurance program on private coverage. Journal of health economics. 2013;32(6):1205-13. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N. Care-Needs Certification in the Long-Term Care Insurance System of Japan. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS). 2005;53(3):522-7. [CrossRef]

- Arai H, Ouchi Y, Toba K, Endo T, Shimokado K, Tsubota K, et al. Japan as the front-runner of super-aged societies: Perspectives from medicine and medical care in Japan: Front-runner of super-aged societies. Geriatrics & gerontology international. 2015;15(6):673-87. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui T. Implementation process and challenges for the community-based integrated care system in Japan. International journal of integrated care. 2014;14(1):e002-e. [CrossRef]

- Yamada M, Arai H, Nishiguchi S, Kajiwara Y, Yoshimura K, Sonoda T, et al. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an independent risk factor for long-term care insurance (LTCI) need certification among older Japanese adults: A two-year prospective cohort study. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2013;57(3):328-32. [CrossRef]

- Yamada M, Hagihara A, Nobutomo K. Family caregivers and care manager support under long-term care insurance in rural Japan. Psychology, health & medicine. 2009;14(1):73-85. [CrossRef]

- Ohwaki K, Hashimoto H, Sato M, Tamiya N, Yano E. Predictors of continuity in home care for older adults under public long-term care insurance in Japan. Aging clinical and experimental research. 2013;21(4-5):323-8. [CrossRef]

- Campbell JC, Ikegami N, Gibson MJ. Lessons From Public Long-Term Care Insurance In Germany And Japan. Health Affairs. 2010;29(1):87-95. [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto Y, Kohara M, Saito M. On the consumption insurance effects of long-term care insurance in Japan: Evidence from micro-level household data. Journal of the Japanese and international economies. 2010;24(1):99-115. [CrossRef]

- Tomita N, Yoshimura K, Ikegami N. Impact of home and community-based services on hospitalisation and institutionalisation among individuals eligible for long-term care insurance in Japan. BMC health services research. 2010;10(1):345-. [CrossRef]

- Tamiya N, Noguchi H, Nishi A, Reich MR, Ikegami N, Hashimoto H, et al. Japan: Universal Health Care at 50 years 4 Population ageing and well-beingwell-being: lessons from Japan's long-term care insurance policy. The Lancet (British edition). 2011;378(9797):1183-92.

- Olivares-Tirado P, Tamiya N, Kashiwagi M. Effect of in-home and community-based services on the functional status of elderly in the long-term care insurance system in Japan. BMC health services research. 2012;12(1):239-. [CrossRef]

- Roigk P, Becker C, Schulz C, König H-H, Rapp K. Long-term evaluation of the implementation of a large fall and fracture prevention program in long-term care facilities. BMC geriatrics. 2018;18(1):233-. [CrossRef]

- Umegaki H, Yanagawa M, Nonogaki Z, Nakashima H, Kuzuya M, Endo H. Burden reduction of caregivers for users of care services provided by the public long-term care insurance system in Japan. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2013;58(1):130-3. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Xu X. Effect Evaluation of the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) System on the Health Care of older adults: A Review. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2020;13:863-75. [CrossRef]

- Washio M, Arai Y, Izumi H, Mori M. Burden on family caregivers of frail elderly persons one year after the introduction of public long term care insurance service in the Onga District, Fukuoka Prefecture: evaluation with a Japanese version of the Zarit caregiver burden interview. Nihon Rōnen Igakkai zasshi. 2003;40(2):147-55. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Fukutomi E, Wada T, Ishimoto Y, Kimura Y, Kasahara Y, et al. Comprehensive geriatric functional analysis of elderly populations in four categories of the long-term care insurance system in a rural, depopulated and aging town in Japan. Geriatrics & gerontology international. 2013;13(1):63-9. [CrossRef]

- Rhee JC, Done N, Anderson GF. Considering long-term care insurance for middle-income countries: comparing South Korea with Japan and Germany. Health policy (Amsterdam). 2015;119(10):1319-29. [CrossRef]

- Fu R, Noguchi H, Kawamura A, Takahashi H, Tamiya N. Spillover effect of Japanese long-term care insurance as an employment promotion policy for family caregivers. Journal of health economics. 2017;56:103-12. [CrossRef]

- Kato RR. The future prospect of long-term care insurance in Japan. Japan and the world economy. 2018;47:1-17. [CrossRef]

- Chandoevwit W, Wasi N. Incorporating discrete choice experiments into policy decisions: Case of designing public long-term care insurance. Social science & medicine (1982). 2020;258:113044-. [CrossRef]

- Ariizumi H. Effect of public long-term care insurance on consumption, medical care demand, and welfare. Journal of health economics. 2008;27(6):1423-35. [CrossRef]

- Bakx P, Schut F, van Doorslaer E. Can universal access and competition in long-term care insurance be combined? International journal of health care finance and economics. 2015;15(2):185-213. [CrossRef]

- Cremer H, Pestieau P. Social long-term care insurance and redistribution. International tax and public finance. 2013;21(6):955-74. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga M, Hashimoto H, Tamiya N. A gap in formal long-term care use related to characteristics of caregivers and households, under the public universal system in Japan: 2001–2010. Health policy (Amsterdam). 2014;119(6):840-9. [CrossRef]

- Fukutomi E, Okumiya K, Wada T, Sakamoto R, Ishimoto Y, Kimura Y, et al. Relationships between each category of 25-item frailty risk assessment (Kihon Checklist) and newly certified older adults under Long-Term Care Insurance: A 24-month follow-up study in a rural community in Japan. Geriatrics & gerontology international. 2015;15(7):864-71. [CrossRef]

- Makizako H, Shimada H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Suzuki T. Impact of physical frailty on disability in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective cohort study. BMJ open. 2015;5(9):e008462-e. [CrossRef]

- Howe AL. Commentary on long-term care insurance and the market for aged care in Japan: LTCI and the market for aged care in Japan. Australasian journal on ageing. 2014;33(3):140-1. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda S, Fujimori K. Development of Integrated Analysis System of Medical and LTCI Claim Data in Japan. Asian Pacific journal of disease management. 2009;3(4):115-20. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Mori T, Sato M, Watanabe T, Noguchi H, Tamiya N. Individual and regional determinants of long-term care expenditure in Japan: evidence from national long-term care claims. European journal of public health. 2020;30(5):873-8. [CrossRef]

| Rank. |

Author |

Was the paper's concentration on a specific issue? |

Do you believe all pertinent, significant research was cited? |

Can the local populace use the results? |

Were all key outcomes taken into account? |

| 1 |

Yamada et al. (2009)[12] |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 2 |

Ohwaki et al. (2009)[13] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

N/A |

| 3 |

Yoshioka et al. (2010)[3] |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

N/A |

| 4 |

Campbell, et al. (2010)[14] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 5 |

Iwamoto et al. (2010)[15] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

No |

| 6 |

Tomita et al. (2010)[16] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

N/A |

| 7 |

Tamiya et al. (2011)[17] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

| 8 |

Olivares-Tirado et al. (2012)[18] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

No |

| 9 |

Washio et al. (2012)[22] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 10 |

Chen et al. (2013)[23] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

N/A |

| 11 |

Umegaki et al. (2014)[20] |

No |

N/A |

Yes |

No |

| 12 |

Rhee et al. (2015)[24] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

No |

| 13 |

Fu et al. (2017)[25] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| 14 |

Saito et al. (2018)[4] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

| 15 |

Kato (2018)[26] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

| 16 |

Kondo (2019)[5] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

N/A |

| 17 |

Chandoevwit&Wasi (2020)[27] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

| 18 |

Ariizumi (2008)[28] |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

| 19 |

Bakx, &Schut&van Doorslaer (2015)[29] |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

N/A |

| 20 |

Cremer&Pestieau(2014)[30] |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).