Submitted:

12 March 2024

Posted:

14 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

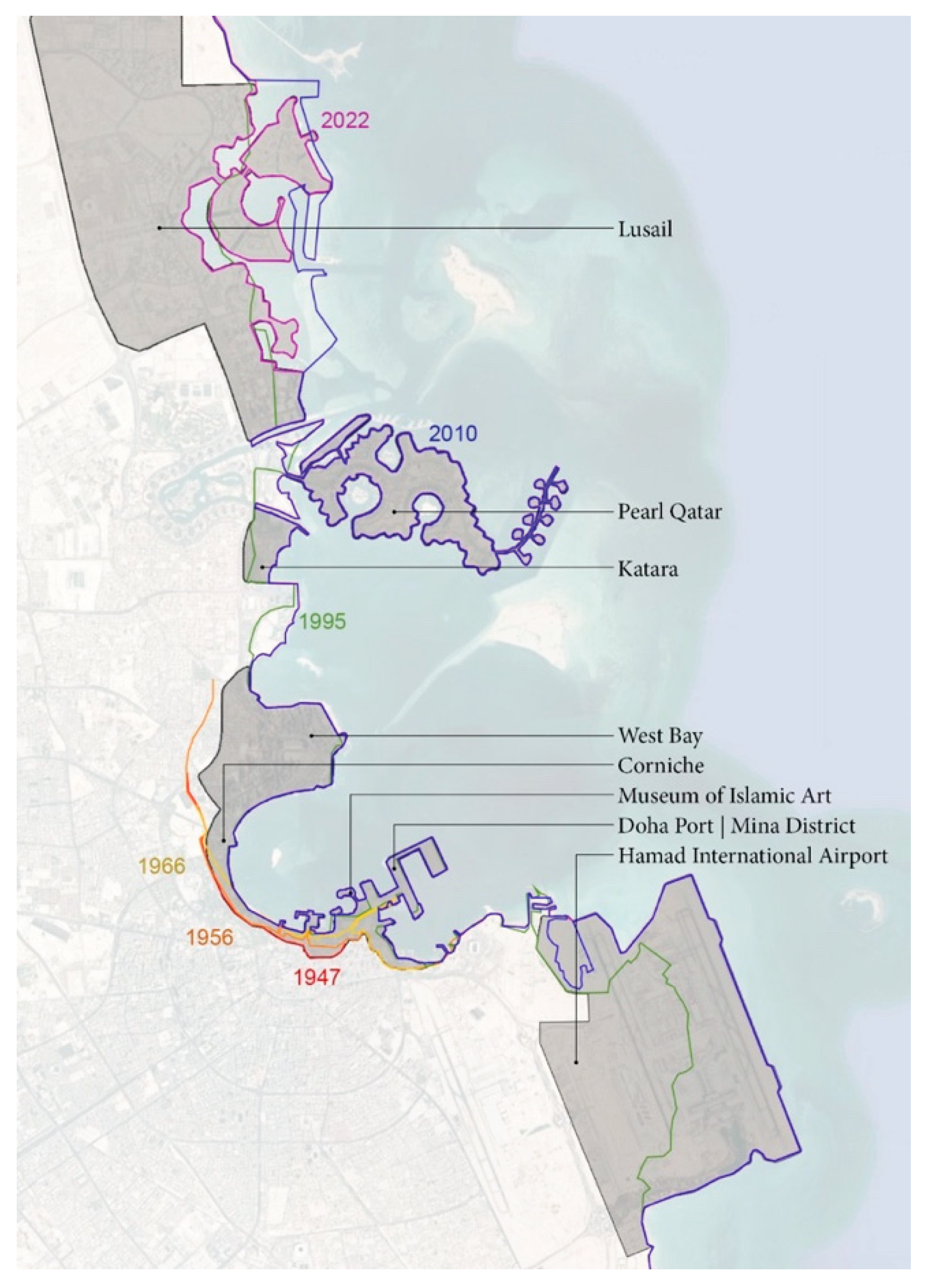

2.1. Land Reclamation in Qatar – Study Area

2.2. Selection of Sustainability Indicators

2.3. Urban Spatial Planning Indicators

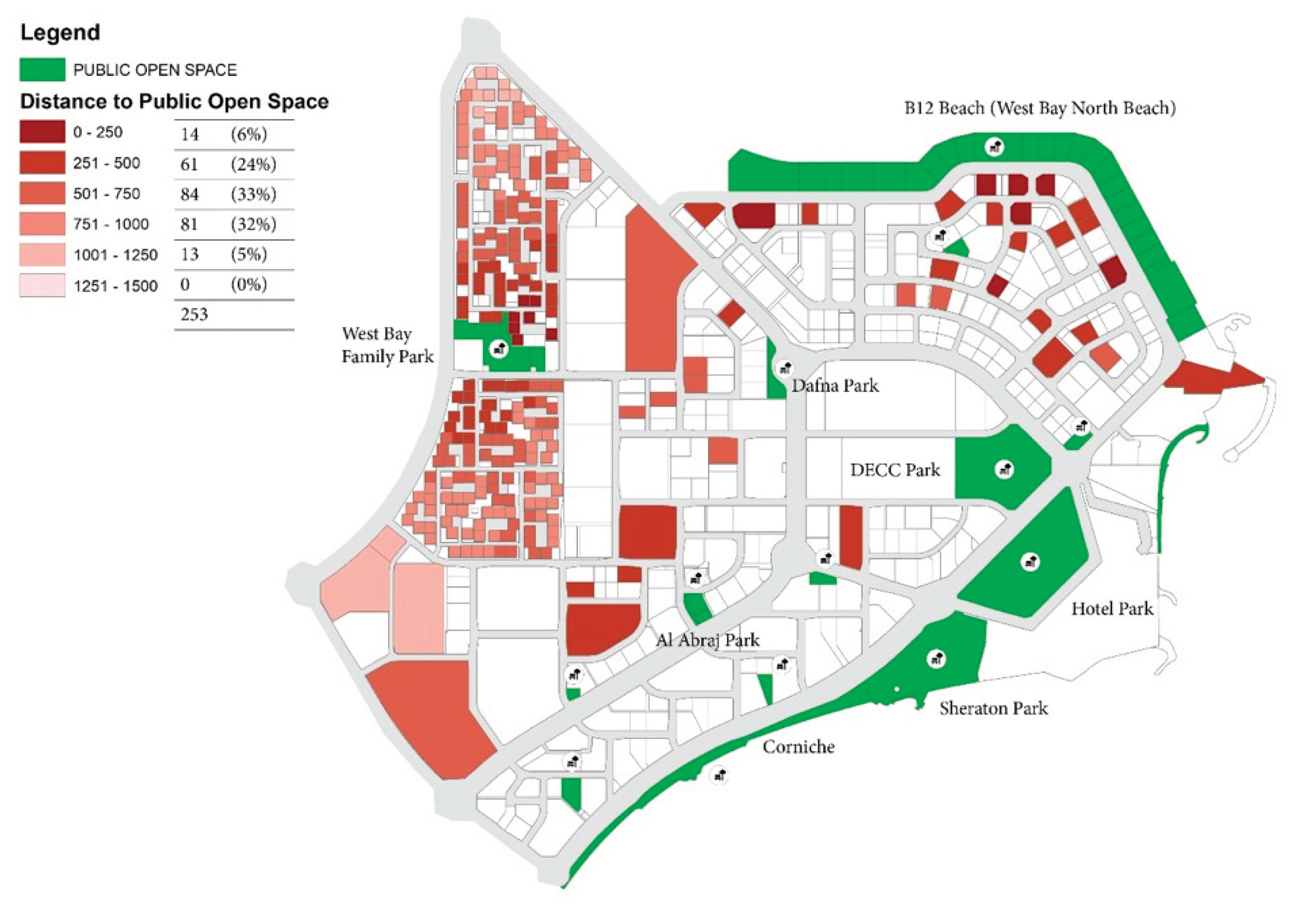

- Open Space Coverage: The World Health Organization (WHO), 2020, defines open space as land covered with vegetation of any kind, including private and public spaces, regardless of their functions. Public open spaces are necessary in an urban environment as they act as green lungs for the city, improving the air quality as well as offering a place of respite. From various studies examining the ratio of open spaces to building fabric, 17% to 32% is the most commonly found range [38,39]. This range applies to high-, medium- and low-density urban areas, independent of townships and dedicated urban areas.

- Land Use Mix: Mixed land use is an important urban planning strategy that involves the integration of different land uses such as residential, commercial, institutional, and industrial within a single neighbourhood or district. For coastal cities, mixed land use can have significant benefits, particularly in terms of improving the resilience against sea level rise, storm surges and coastal erosions, improving the sustainability of the built environment and socio-economic fabric. Urban theorists consider land-use mix to be one of the most important tools for planning for sustainability [40]. Mixed-use neighbourhoods are sustainable since they reduce the use of cars to access other missing uses. A very diverse mix of uses provides access to a variety of facilities within shorter distances enabling people to walk or cycle to them as discussed by Moreno et al. (2021) [41].

- Coast for the public realm: The coast is an important public realm that has played a significant role in the development of many urban areas around the world. Coastal areas offer a wide range of opportunities for urban development and social interaction, including public spaces, parks, beaches, recreation areas, and commercial and residential developments. A study by Pittman et al. (2019) found that the creation of new land on the coast has facilitated the development of new urban centres, transportation infrastructure, and public amenities and concluded that the development of the coast as a public realm is essential for promoting sustainable urban development [42]. Similarly, a study in Al-Arish City, Egypt found that the redevelopment of the coast for the public realm has the potential to enhance social interaction, provide recreational opportunities, and create a sense of place for residents and visitors [43].

- Accessibility to Public Transportation: Accessibility to public transportation is a critical element of urban planning in coastal cities, providing numerous benefits such as reduced traffic congestion, improved mobility, reduced car dependency, enhanced economic development, and enhanced social inclusion [44]. It is particularly important in coastal cities where the coast is a key destination and can provide convenient and sustainable access to coastal amenities for residents and visitors alike. Public transportation can provide convenient, affordable and equitable access to beaches, waterfronts, and other coastal amenities, reducing the demand for private cars and parking [45].

- Accessibility to amenities: Accessibility to schools, healthcare facilities, and parks are crucial factors for urban development on reclaimed land. These amenities contribute to creating liveable communities and enhancing the quality of life for residents. Studies have shown that the presence of these amenities in a neighbourhood significantly impacts property values and attracts businesses, contributing to economic growth and social stability [46,47]. For example, in the development of the Marina Bay area in Singapore, accessibility to public amenities such as schools, healthcare facilities, and parks was prioritized in the planning process. This has contributed to the area’s success as a desirable location for living, working, and recreation [48].

- Pedestrian walkways: Availability and accessibility to pedestrian walkways provide safe, efficient, and sustainable mobility. Studies have shown that walkability and pedestrian-friendly design can have significant positive impacts on the economic, social, and environmental aspects of urban areas [49] and contribute to the safety and security of the area, by reducing the risks of accidents and crimes, and by increasing the visibility and informal surveillance of public spaces [50].

- Cycling tracks: Cycling infrastructure promotes sustainable transportation and helps to reduce air and noise pollution. Studies have shown that investment in cycling infrastructure leads to a net positive economic benefit by reducing the cost of infrastructure maintenance and public health expenditures [51].

- Adequate road network: A well-planned road network leads to economic benefits and improves the quality of life for residents by providing access to recreational areas and reducing travel times. For example, in the case of Hong Kong, the construction of a comprehensive road network has been essential to the development of the city. The government has invested in developing a road network that connects different parts of the city and links it to other parts of the region. This has led to increased economic activity, improved accessibility to jobs and services, and improved living conditions for residents [52].

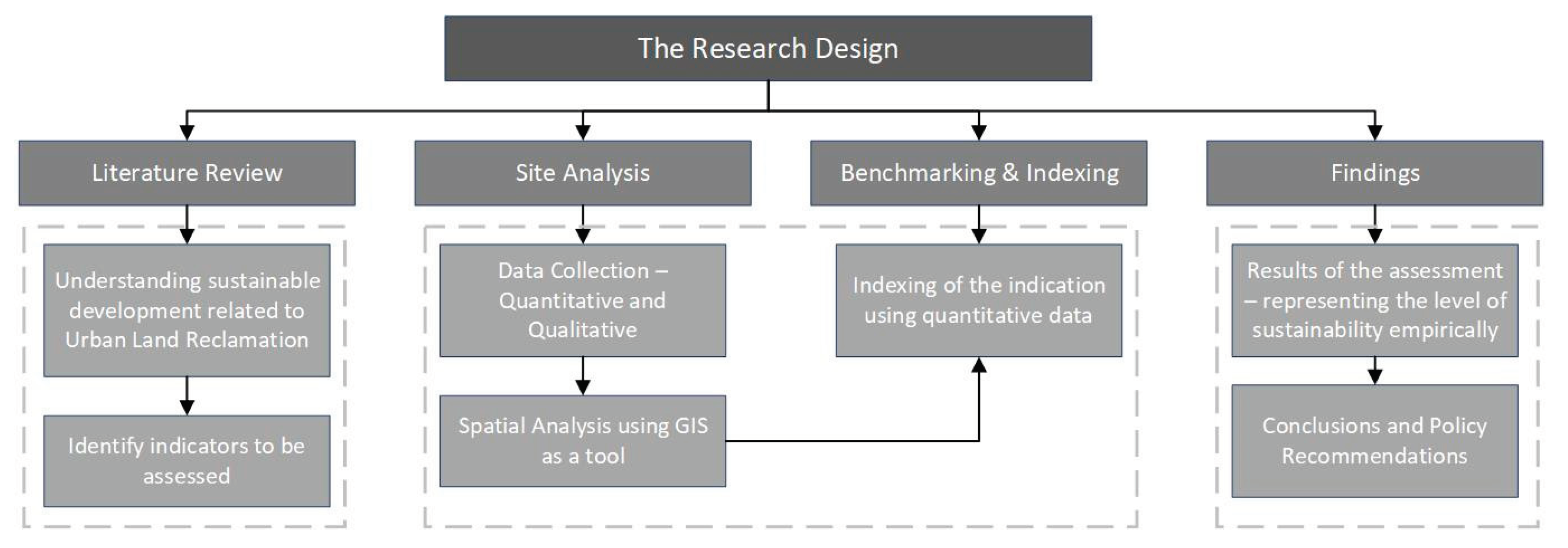

3. The Research Design

3.1. Literature Review

3.2. Site Analysis

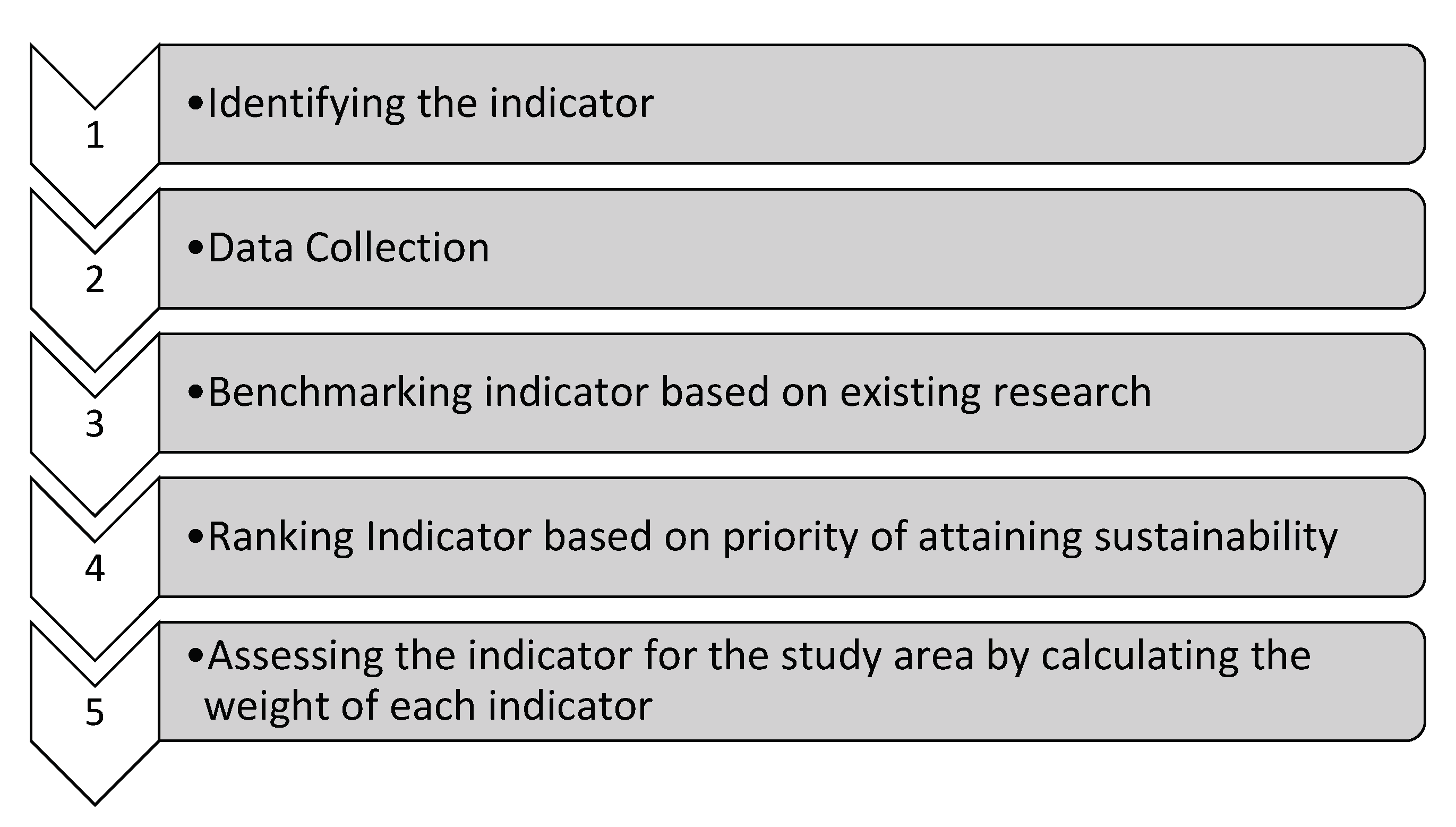

3.3. Benchmarking and Indexing Assessment Indicators

3.4. Assessment and Recommendations

4. Findings

4.1. Open Space Coverage

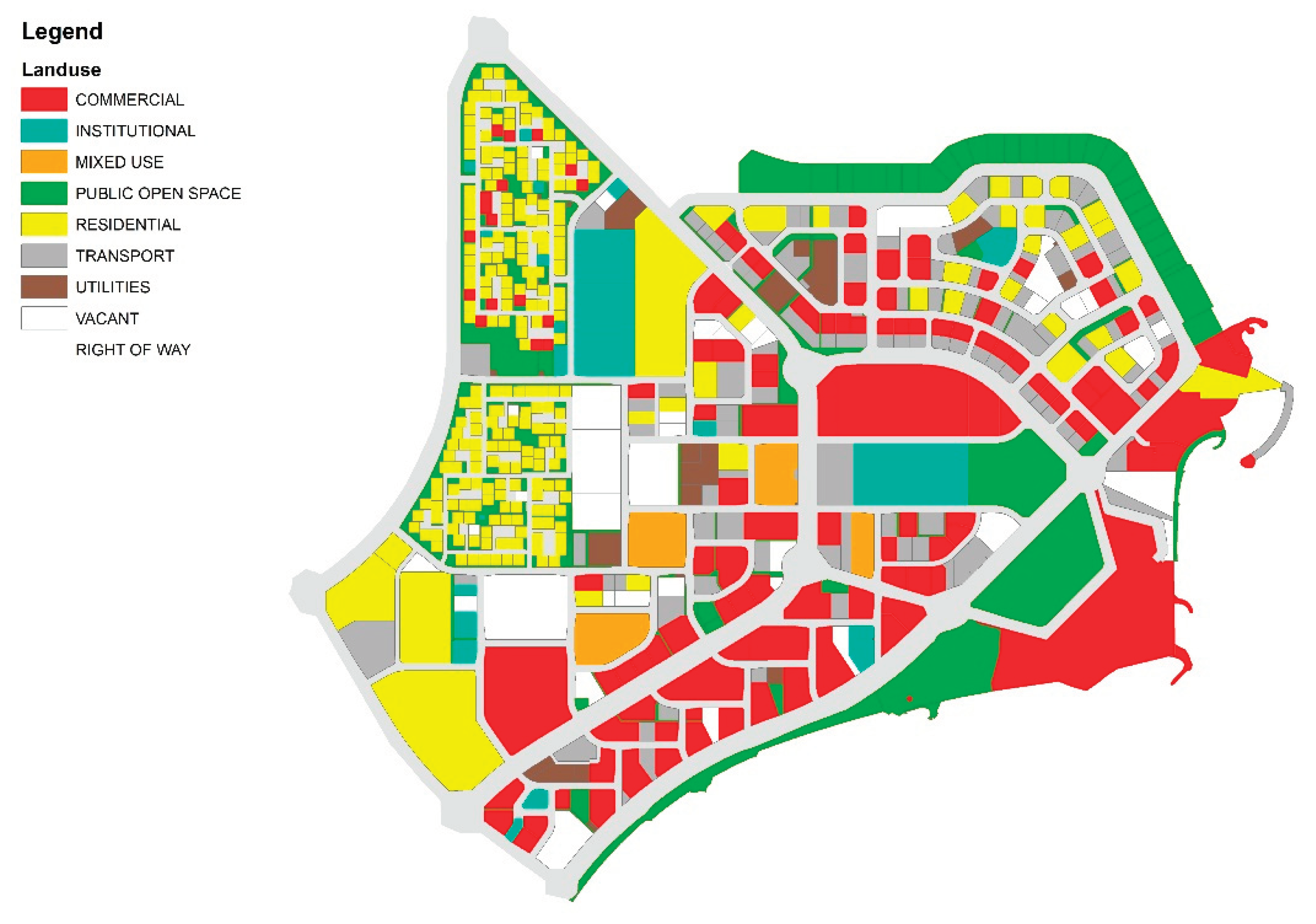

4.2. Land Use Mix

| Area (sqm) | % of Total | % of Developable | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right Of Way | 1,308,997 | 28% | |

| Residential | 670,905 | 15% | 20% |

| Public open space | 601,225 | 13% | 18% |

| Commercial | 942,849 | 21% | 29% |

| Vacant | 309,106 | 7% | 9% |

| Institutional | 206,083 | 4% | 6% |

| Mixed use | 97,054 | 2% | 3% |

| Utilities | 90,531 | 2% | 3% |

| Transport | 370,917 | 8% | 11% |

| TOTAL AREA: | 4,597,667 | ||

| TOTAL DEVELOPABLE AREA: | 3,288,670 |

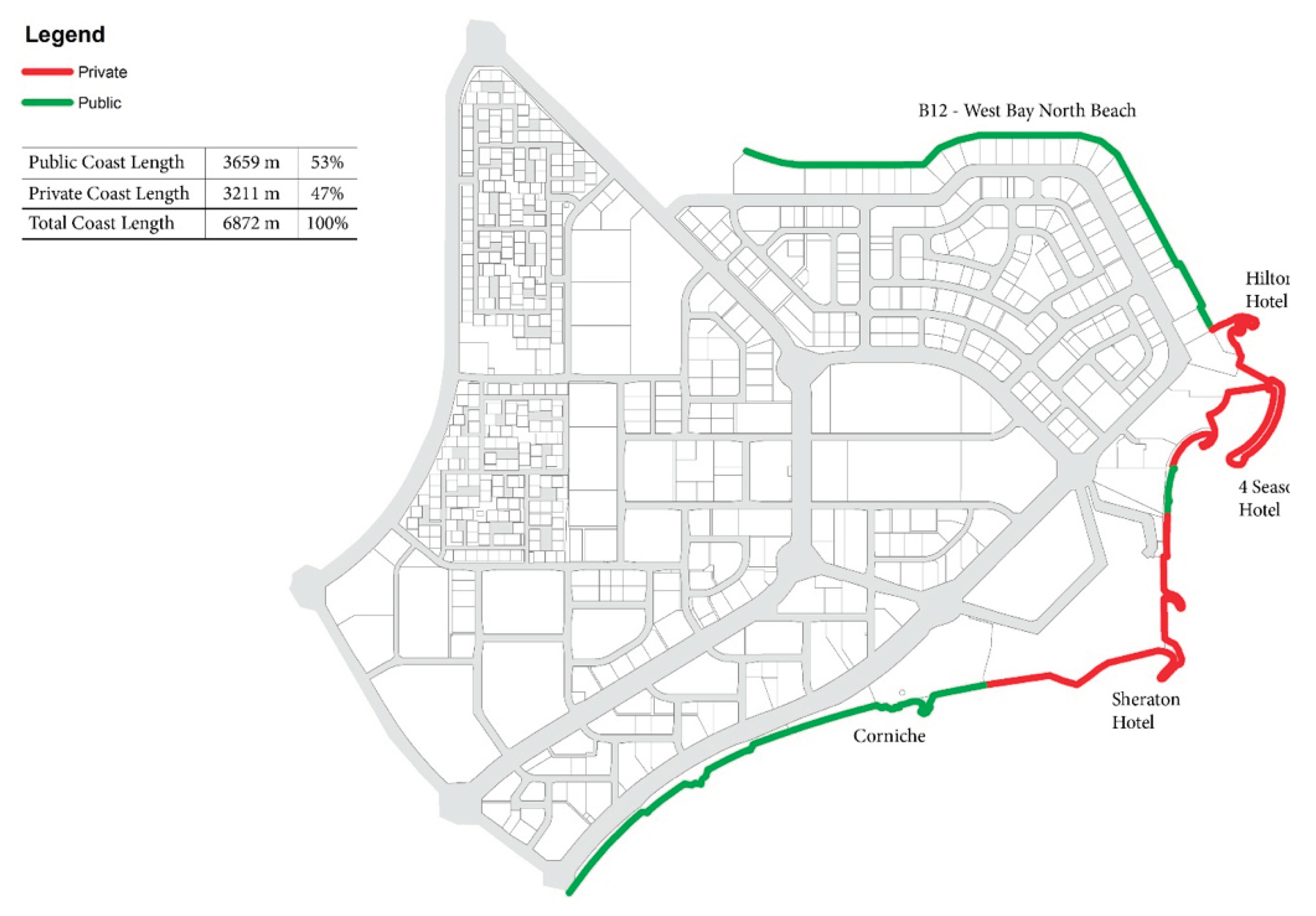

4.3. Coast for the Public Realm

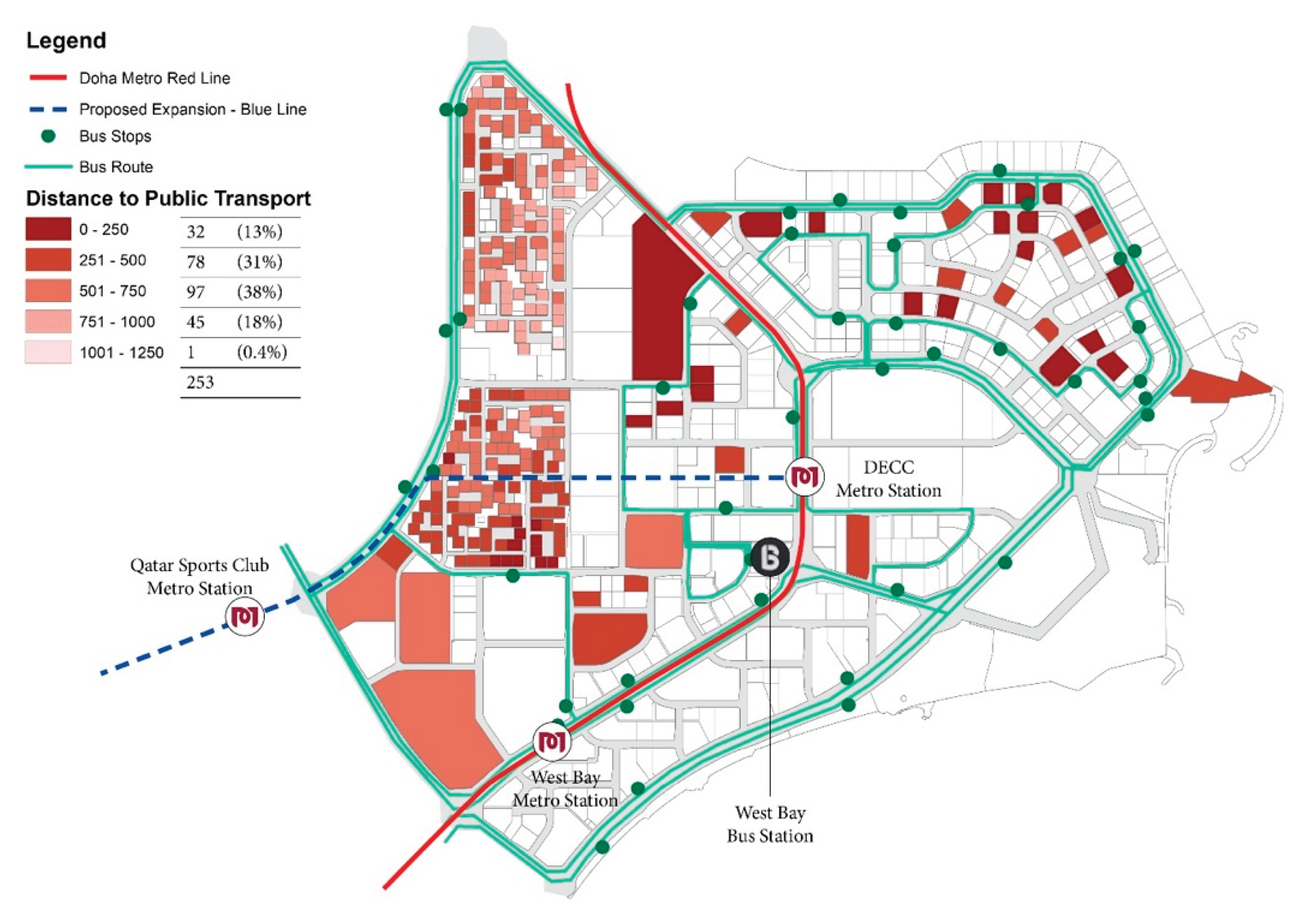

4.4. Accessibility to Public Transportation

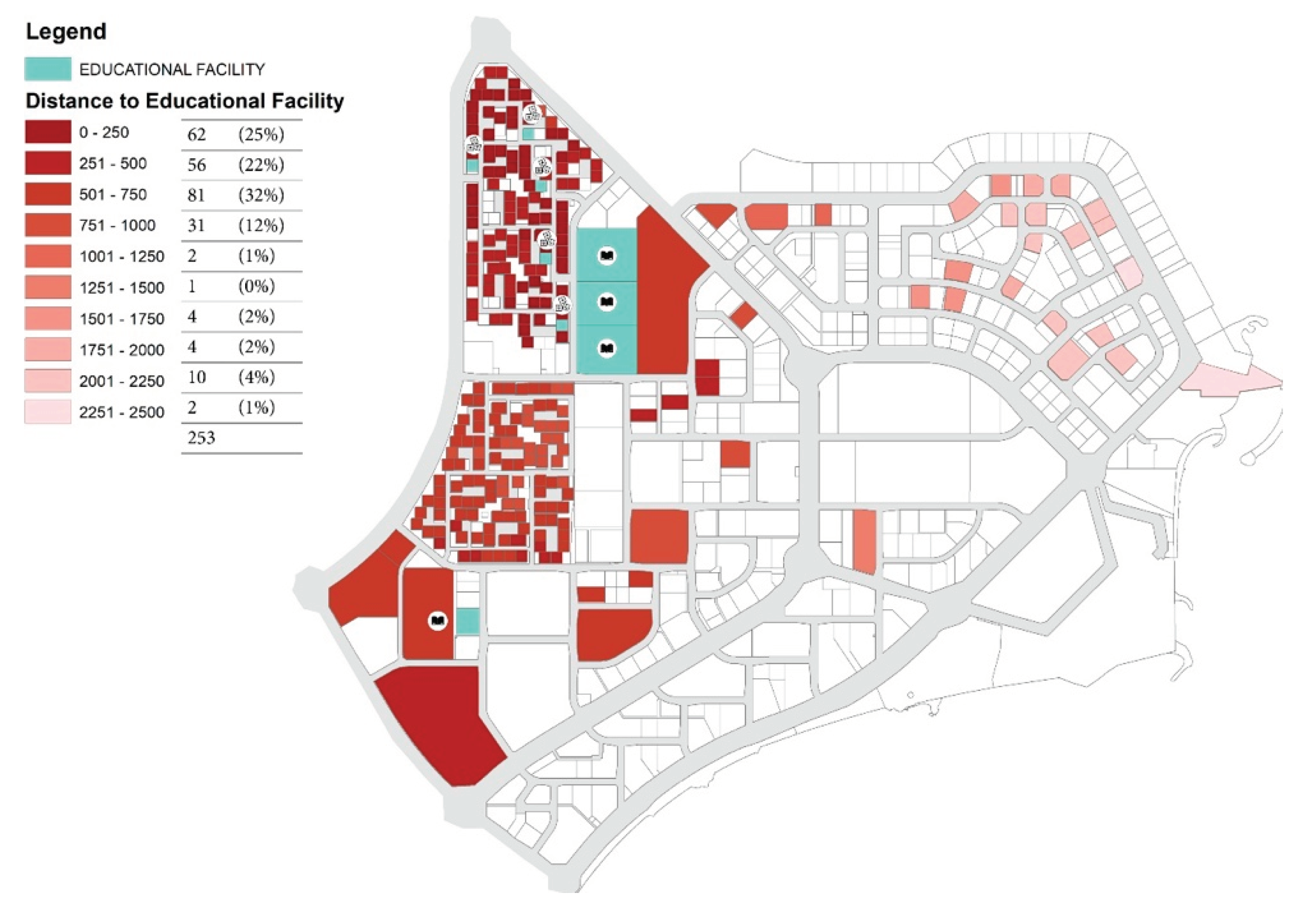

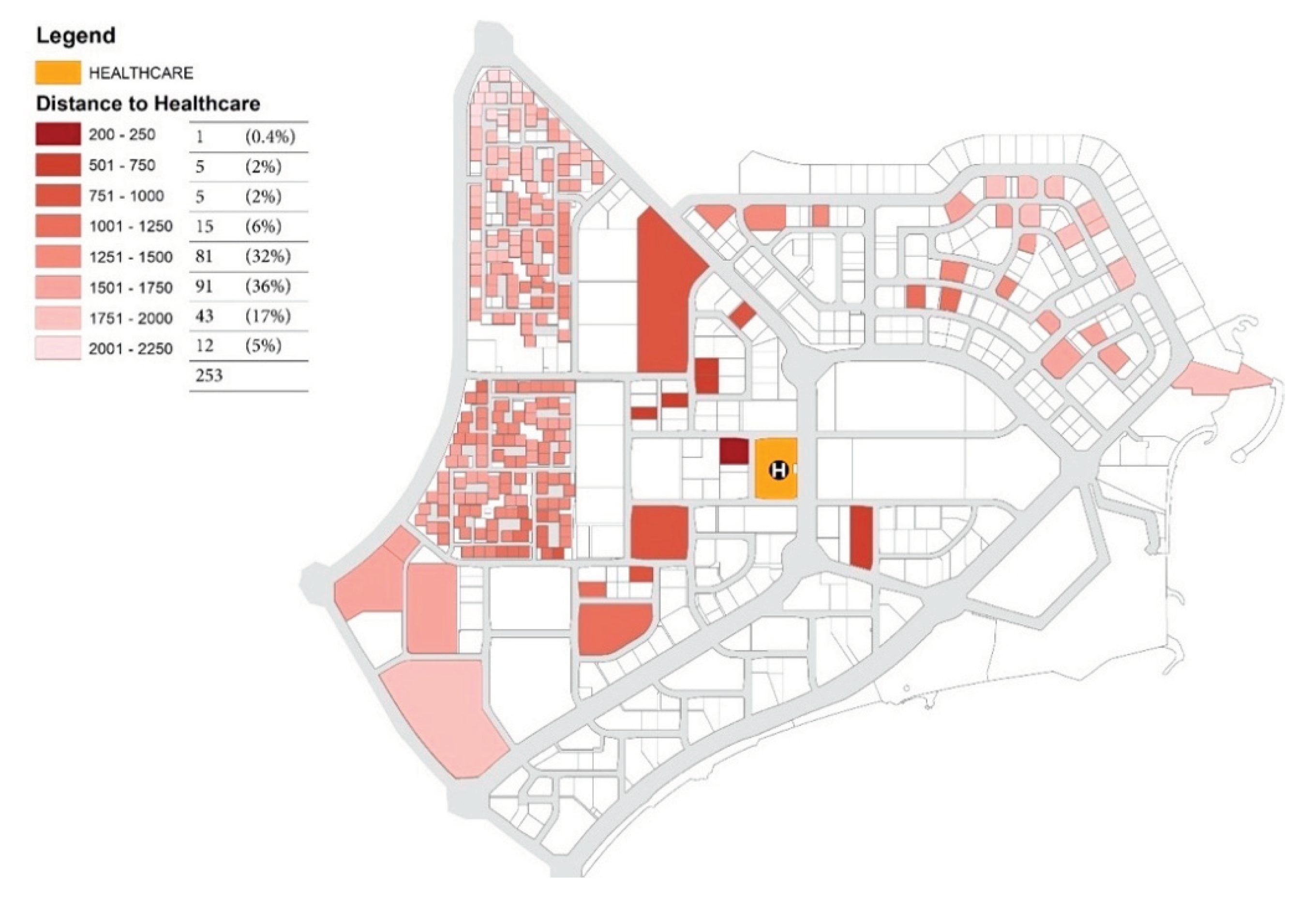

4.5. Accessibility to Amenities

4.6. Pedestrian Pathways

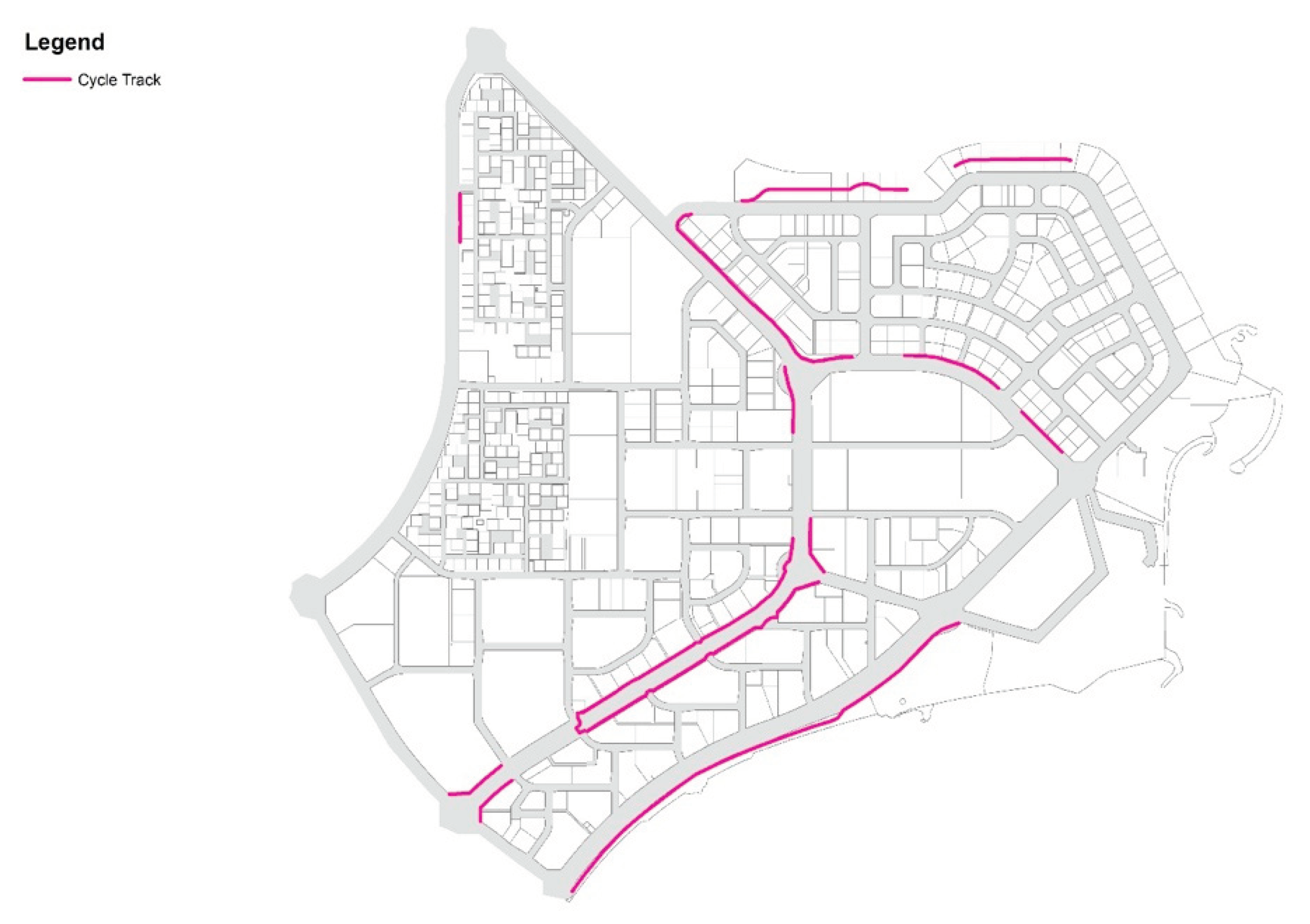

4.7. Cycle Tracks

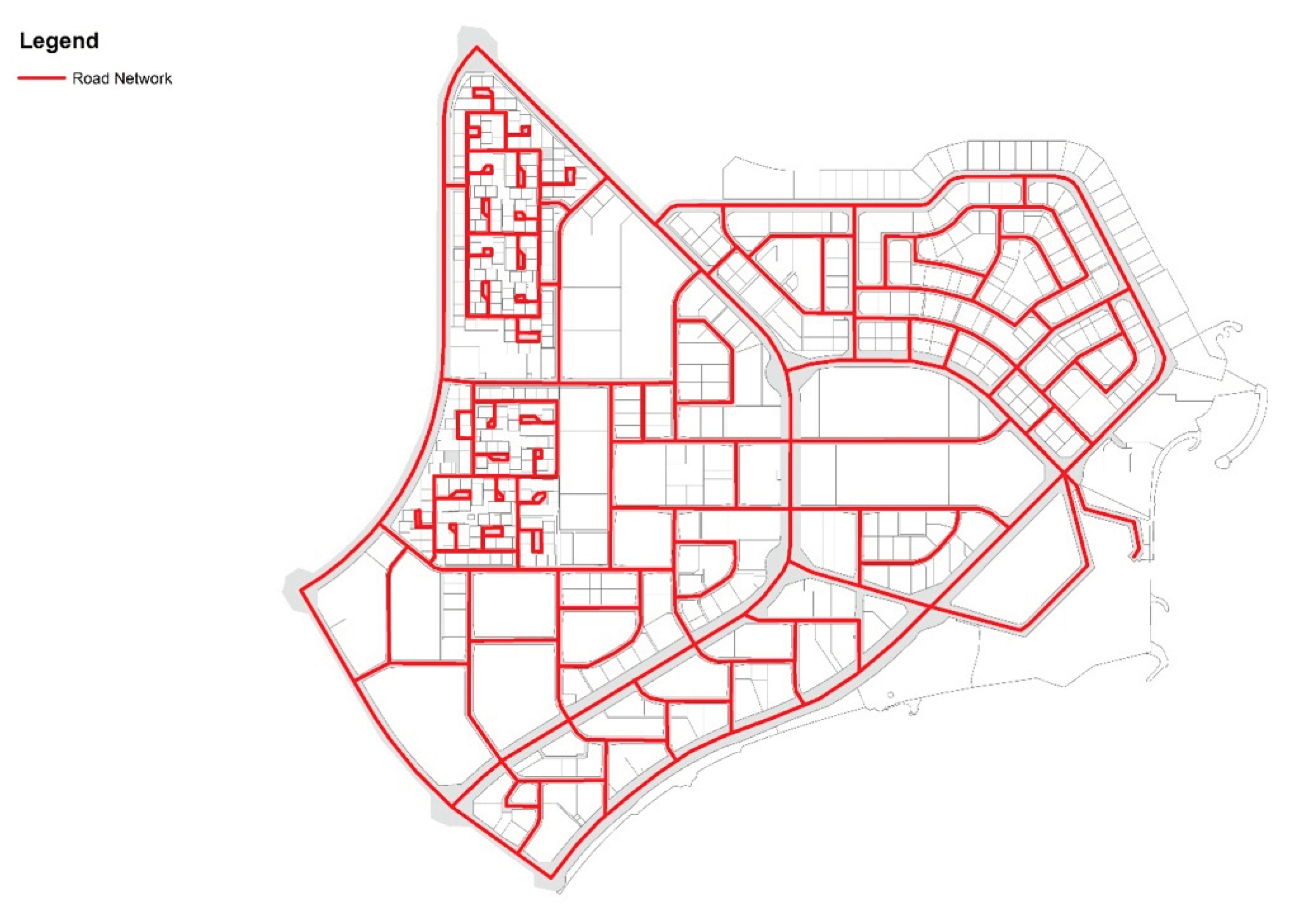

4.8. Adequate Road Network

| No. | Indicator | Benchmarks | Benchmark value for this study (A) | West Bay Score (A) | Weight for indicator (B) | (A*B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unacceptable (1) | Acceptable (2) | Optimum (3) | ||||||

| 1 | Open space coverage | Ratio to the total area | 17 – 22% | 23 – 18% | 28% + | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | Land use mix | Entropy index | 0 – 0.5 | 0.5 – 0.75 | 0.75 - 1 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| 3 | % of coast for people | % of the coastline | 30 – 50% | 50 – 70% | 70% + | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| 4 | Accessibility to public transport | % of people that can access within 750 meters | 50 – 60% | 60 – 75% | 75% + | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| 5 | Accessibility to amenities | % of people that can access within 750 meters | 50 – 60% | 60 – 75% | 75% + | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | Pedestrian paths | % of pedestrian path compared to road network | < 50% | 50 to 80% | > 80% | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| 7 | Cycling tracks | % of cycle track compared to road network | < 50% | 50 to 80% | > 80% | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8 | Adequate road network | % of road network compared to total developable land | >30% | 15 – 30% | <15% | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Weighted Score: | (SUM A*B)/SUM B35/17 = 2.05 | |||||||

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- Open space coverage falls in the unacceptable range. Efficient open spaces must be planned to make the best use of available land, provide a variety of functions (e.g., active and passive recreation, greenery, water features, etc.), and be designed in a way that maximizes their usability, sustainability, and maintenance.

- The land use is diversified and categorized in the optimum range. This indicates that the land use in the area is considered well-balanced, diverse, and appropriate, taking into consideration the goals, objectives, and principles of sustainable urban development.

- While a large part of the coast is reserved for the public realm, there are private coasts that are inaccessible to people. Making the coast optimum for the public policies related to private ownership of coastal land, establishing public easements or access points, creating public waterfronts or promenades, and ensuring that coastal areas are designed and managed in a way that promotes inclusivity, accessibility, and sustainability.

- Accessibility to public transportation and provision of pedestrian pathways fall under the optimum range. This implies that the assessed area has a well-connected and efficient public transportation system that provides convenient and reliable options for people to travel within and beyond the area.

- Accessibility to amenities and provision of cycling tracks fall under the unacceptable range. This implied that public amenities in West Bay are not easily accessible, well-distributed, and available within a reasonable distance for the residents and visitors of the area. Inadequate accessibility to amenities impacts the quality of life, well-being, and liveability of the area, and needs to be addressed through better urban planning, design, and policy interventions.

- The adequacy and efficiency of road networks fall under the acceptable range. This implies that West Bay has a road network that is considered satisfactory in terms of meeting the transportation needs of the area and maintaining reasonable traffic flow. However, interventions must be implemented to make it to an optimum level with further research.

- Environmental Impact: Reclaimed lands often have unique ecological characteristics, including fragile ecosystems, wildlife habitats, and coastal ecosystems that may be vulnerable to disturbance or destruction during the development process. Sustainable urban development on reclaimed lands aims to minimize negative impacts on the environment, including protecting natural habitats, preserving biodiversity, and mitigating potential risks such as sea level rise and coastal erosion.

- Social Impact: Urban development on reclaimed lands can have significant social implications for local communities, including changes in land ownership, displacement of existing populations, and impacts on cultural heritage. Sustainable urban development should take into account the social aspects of land reclamation, including ensuring equitable access to housing, amenities, and public spaces, engaging local communities in decision-making processes, and addressing social and cultural impacts in a responsible manner.

- Economic Impact: Reclaimed lands are often prime real estate for urban development, and the economic benefits can be substantial. However, sustainability considerations are essential to ensure long-term economic viability. This includes factors such as optimizing land use, promoting economic diversity, integrating green and blue infrastructure, and adopting resilient design and construction practices to reduce long-term risks and costs associated with climate change impacts.

- Resilience to Climate Change: Reclaimed lands are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, such as sea level rise, storm surges, and extreme weather events. Sustainable urban development on reclaimed lands should incorporate strategies to enhance resilience to these impacts, including appropriate setback distances from coastlines, green and blue infrastructure to absorb and manage stormwater, and adaptive design measures that consider future climate projections.

- Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Sustainable urban development on reclaimed lands aligns with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 11, which focuses on making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. By prioritizing sustainability in urban development on reclaimed lands, it contributes to global efforts towards achieving sustainable urbanization and protecting the environment for present and future generations.

- Urban planning must prioritize the creation and preservation of open space on urban reclaimed land, by requiring developers to dedicate a percentage of the land to public parks and gardens, and by encouraging the preservation and restoration of natural habitats. In addition, planners must encourage the use of green infrastructure such as bioswales and rain gardens to manage stormwater runoff and mitigate the impact of coastal hazards.

- The coast must be designed for the public realm by prioritizing pedestrian access, providing public amenities such as seating, restrooms, and drinking fountains, and creating public spaces that welcome all members of the community, regardless of income or background. This can be achieved by creating a public-private partnership involving stakeholders in the development and maintenance of the public space.

- Policies must prioritize the development of mixed-use neighbourhoods including residential, commercial, and industrial uses in close proximity to each other. In addition, planners must encourage the use of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), which involves building compact, walkable communities around public transit stations.

- Urban planning must improve access to public transport and amenities by investing in public transport infrastructure, such as light rail, express buses and bicycle rental systems. In addition, planners must encourage the development of mixed-use developments that include essential services such as grocery stores, healthcare facilities, and schools [62,63].

- Urban planning must prioritize the development of pedestrian walkways by designing streets that prioritize pedestrian safety, creating pedestrian-only streets, and promoting the use of pedestrian-friendly technologies such as smart crosswalks and pedestrian countdown signals. Additionally, planners must encourage the development of “complete streets” that accommodate pedestrians, cyclists, and public transit users.

- Planners must promote the development of cycle tracks by creating dedicated bike lanes, providing bike-sharing systems, and promoting the use of e-bikes and other sustainable transportation options. Planners must prioritize the development of safe and connected bike networks that are integrated with public transit systems.

5. Contribution to Knowledge

6. Implication of Practice for the Advancement of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. R. Stuchtey et al., “Ocean Solutions That Benefit People, Nature and the Economy,” in The Blue Compendium, J. Lubchenco and P. M. Haugan, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023, pp. 783–906. [CrossRef]

- D. Sengupta et al., “Mapping 21st Century Global Coastal Land Reclamation,” Earth’s Future, vol. 11, no. 2, p. e2022EF002927, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Bhunia, U. Chatterjee, and P. K. Shit, “Emergence and challenges of land reclamation: issues and prospect,” in Modern Cartography Series, vol. 10, Elsevier, 2021, pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- E. Burton, M. Jenks, and K. Williams, Eds., Achieving Sustainable Urban Form, 0 ed. Routledge, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Our Common Future, “World Commission on Environment and Development,” Statutory Report, 1987. [Online]. Available: un.org.

- M. de Lange, “A closer look into the feasibility of future, large scale land reclamation.

- M. Al-Saidi, “Coastal Development and Climate Risk Reduction in the Persian/Arabian Gulf: The Case of Qatar,” in Climate Change and Ocean Governance, 1st ed., P. G. Harris, Ed., Cambridge University Press, 2019, pp. 60–74. [CrossRef]

- M. AlQahtany et al., “Land Reclamation in a Coastal Metropolis of Saudi Arabia: Environmental Sustainability Implications,” Water, vol. 14, no. 16, p. 2546, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Al-Saidi, “Disentangling the SDGs agenda in the GCC region: Priority targets and core areas for environmental action,” Front. Environ. Sci., vol. 10, p. 1025337, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Arch. S. Patel, D. M. Indraganti, and D. R. Jawarneh, “Land Surface Temperature Responses to Land Use Dynamics in Urban Areas of Doha, Qatar,” Sustainable Cities and Society, p. 105273, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Furlan, S. Zaina, and S. Patel, “The urban regeneration’s framework for transit villages in Qatar: the case of Al Sadd in Doha,” Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 5920–5936, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Naimi, G. Karani, and J. Littlewood, “Stakeholder Views on Land Reclamation and Marine Environment in Doha, Qatar,” JAES, vol. 6, no. 1, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Furlan, “The urban regeneration of west bay, business district of Doha (state of Qatar),” JHAAS, vol. 3, no. 5, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ge and Z. Jun-yan, “Analysis of the impact on ecosystem and environment of marine reclamation--A case study in Jiaozhou Bay,” Energy Procedia, vol. 5, pp. 105–111, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Afzal, F. Tahir, and S. G. Al-Ghamdi, “Recommendations and Strategies to Mitigate Environmental Implications of Artificial Island Developments in the Gulf,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 5027, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. K. A. Morny, T. H. Margrain, A. M. Binns, and M. Votruba, “Electrophysiological ON and OFF Responses in Autosomal Dominant Optic Atrophy,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, vol. 56, no. 13, pp. 7629–7637, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Schrenk, Ed., REAL CORP 2012 - re-mixing the city: towards sustainability and resilience? ; proceedings of 17th International Conference on Urban Planning, Regional Development and Information Society ; Beiträge zur 17. Internationalen Konferenz zu Stadtplanung, Regionalentwicklung und Informationsgesellschaft ; [Multiversum Schwechat, Austria, 14 - 16 May 1012 ; Tagungsband]. Schwechat-Rannersdorf: Selbstverl. des Vereins CORP - Competence Center of Urban and Regional Planning, 2012.

- “Lusail city.” Doha, 2013. [Online]. Available: https://www.lusail.com/.

- Middle East, “The Pearl-Qatar,” Arabian Business, Doha, Qatar, Sep. 19, 2009. [Online]. Available: https://www.arabianbusiness.com/industries/construction/the-pearl-qatar-12768.

- M. D. Major and H. O. Tannous, “Form and Function in Two Traditional Markets of the Middle East: Souq Mutrah and Souq Waqif,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 17, p. 7154, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dredging Today, “DEME: Doha Airport Built on Reclaimed Land Becomes Fully Operational,” Jun. 03, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.dredgingtoday.com/2014/06/03/deme-doha-airport-built-on-reclaimed-land-becomes-fully-operational/.

- R. Furlan et al., “The urban regeneration of west-bay, business district of Doha (State of Qatar): A transit-oriented development enhancing livability,” Journal of Urban Management, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 126–144, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Al-Jamali, J. M. Bishop, J. Osment, D. A. Jones, and L. LeVay, “A review of the impacts of aquaculture and artificial waterways upon coastal ecosystems in the Gulf (Arabian/Persian) including a case study demonstrating how future management may resolve these impacts,” Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 81–94, Jan. 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Nagy, “Dressing Up Downtown: urban development and government public image in Qatar,” City & Society, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 125–147, Jun. 2000. [CrossRef]

- V. Mirincheva, F. Wiedmann, and A. M. Salama, “The Spatial Development Potentials of Business Districts in Doha: The Case of the West Bay,” OHI, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 16–26, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Abdelkarim, A. M. Ahmad, S. Ferwati, and K. Naji, “Urban Facility Management Improving Livability through Smart Public Spaces in Smart Sustainable Cities,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 23, p. 16257, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Al-Thani and M. Koç, “In Search of Sustainable Economy Indicators: A Comparative Analysis between the Sustainable Development Goals Index and the Green Growth Index,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 4, p. 1372, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Alattar, R. Furlan, M. Grosvald, and R. Al-Matwi, “West Bay Business District in Doha, State of Qatar: Envisioning a Vibrant Transit-Oriented Development,” Designs, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 33, 21. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- D. Boussaa, “Urban Regeneration and the Search for Identity in Historic Cities,” Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 48, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Patel, T. Karanisa, and M. Abdel Khalek, “Backyard Urban Agriculture in Qatar: Challenges & Recommendations,” in Environmental Network Journal, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate. 3539.

- Yurnita, S. Trisutomo, and M. Ali, “Developing sustainability index measurement for reclamation area,” 4th International Conference on Sustainable Built Environment, 2016.

- S. A. Azwar, E. Suganda, P. Tjiptoherijanto, and H. Rahmayanti, “Model of Sustainable Urban Infrastructure at Coastal Reclamation of North Jakarta,” Procedia Environmental Sciences, vol. 17, pp. 452–461, 2013. [CrossRef]

- N. M. P. De Alencar, M. Le Tissier, S. K. Paterson, and A. Newton, “Circles of Coastal Sustainability: A Framework for Coastal Management,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 4886, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Hu, J. Fan, H. Hou, Y. Li, Y. Li, and K. Huang, “Long-term monitoring and evaluation of land development in a reclamation area under rapid urbanization: A case-study in Qiantang New District, China,” Land Degrad Dev, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 3259–3271, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Bahadure and R. Kotharkar, “Framework for measuring sustainability of neighbourhoods in Nagpur, India,” Building and Environment, vol. 127, pp. 86–97, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Lupardus, A. C. S. McIntosh, A. Janz, and D. Farr, “Succession after reclamation: Identifying and assessing ecological indicators of forest recovery on reclaimed oil and natural gas well pads,” Ecological Indicators, vol. 106, p. 105515, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Adesipo, D. Freese, S. Zerbe, and G. Wiegleb, “An Approach to Thresholds for Evaluating Post-Mining Site Reclamation,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 10, p. 5618, 21. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- W. Chi, J. Jia, T. Pan, L. Jin, and X. Bai, “Multi-Scale Analysis of Green Space for Human Settlement Sustainability in Urban Areas of the Inner Mongolia Plateau, China,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 17, p. 6783, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Yin, P. Fu, A. Cheshmehzangi, Z. Li, and J. Dong, “Investigating the Changes in Urban Green-Space Patterns with Urban Land-Use Changes: A Case Study in Hangzhou, China,” Remote Sensing, vol. 14, no. 21, p. 5410, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Koe, “Urban Vitality through a Mix of Land-uses and Functions: An Addition to Citymaker,” Minor thesis, Wageningen University and Research Centre, Wageningen, The Netherlands., 2013.

- C. Moreno, Z. Allam, D. Chabaud, C. Gall, and F. Pratlong, “Introducing the ‘15-Minute City’: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities,” Smart Cities, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 93–111, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Pittman et al., “Marine parks for coastal cities: A concept for enhanced community well-being, prosperity and sustainable city living,” Marine Policy, vol. 103, pp. 160–171, 19. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Rizk Hegazy, “Towards sustainable urbanization of coastal cities: The case of Al-Arish City, Egypt,” Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 2275–2284, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. O. Tannous, R. Furlan, and M. D. Major, “Souq Waqif Neighborhood as a Transit-Oriented Development,” J. Urban Plann. Dev., vol. 146, no. 4, p. 05020023, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Furlan, A. Al-Mohannadi, M. D. Major, and T. N. K. Paquet, “A planning method for transit villages in Qatar: Souq Waqif historical district in Doha,” OHI, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 425–446, 23. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- H. O. Tannous, M. D. Major, and R. Furlan, “Accessibility of green spaces in a metropolitan network using space syntax to objectively evaluate the spatial locations of parks and promenades in Doha, State of Qatar,” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, vol. 58, p. 126892, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Al Fadala, R. Furlan, R. Awwaad, K. L. Marthya, and O. Tagwa, “Strategies for the urban regeneration of the Museum of Islamic Art Park in Doha, Qatar,” Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 318–339.

- G. Ollivier and D. Djalal, “Transit-oriented development and the case of the Marina Bay area in Singapore.” [Online]. Available: https://blogs.worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/transit-oriented-development-and-case-marina-bay-area-singapore.

- R. Furlan, B. R. Sinclair, and R. Awwaad, “Toward Sustainable Urban Development in Doha: Implementation of Transit Villages through a Multiple-Layer Analysis,” J. Urban Plann. Dev., vol. 149, no. 4, p. 05023038, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, The death and life of great American cities, Vintage Books ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1992.

- WHO, “Cycling and walking can help reduce physical inactivity and air pollution, save lives and mitigate climate change.” [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/07-06-2022-cycling-and-walking-can-help-reduce-physical-inactivity-and-air-pollution--save-lives-and-mitigate-climate-change. 2022.

- M. Burdett, “Case study of transport infrastructure: Hong Kong.” [Online]. Available: https://geographycasestudy.com/case-study-of-transport-infrastructure-hong-kong/.

- M. Kim, S. You, J. Chon, and J. Lee, “Sustainable Land-Use Planning to Improve the Coastal Resilience of the Social-Ecological Landscape,” Sustainability, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 1086, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Bordoloi, A. Mote, P. P. Sarkar, and C. Mallikarjuna, “Quantification of Land Use Diversity in The Context of Mixed Land Use,” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 104, pp. 563–572, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Port of Rotterdam, “Rotterdam Mainport Development Project,” Design report, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.portofrotterdam.com/en/building-port/ongoing-projects/rotterdam-mainport-development-project.

- Al-Malki, R. Awwaad, R. Furlan, M. Grosvald, and R. Al-Matwi, “Transit-Oriented Development and Livability: The Case of the Najma and Al Mansoura Neighborhoods in Doha, Qatar,” UP, vol. 7, no. 4, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Furlan, M. Grosvald, and A. Azad, “A social-ecological perspective for emerging cities: The case of Corniche promenade, ‘urban majlis’ of Doha,” J Infrastruct Policy Dev, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 1496, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Al-Mohannadi, R. Awwaad, R. Furlan, M. Grosvald, R. Al-Matwi, and R. J. Isaifan, “Sustainable Status Assessment of the Transit-Oriented Development in Doha’s Education City,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 1913, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. De Haas and M. Schepers, “Wetland Reclamation and the Development of Reclamation Landscapes: A Comparative Framework,” Journal of Wetland Archaeology, vol. 22, no. 1–2, pp. 75–96, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- City of Copenhagen, “The city of Copenhagen’s Bicycle Strategy,” Progress report, 2010. Accessed: Mar. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://use.metropolis.org/case-studies/cycling-in-copenhagen.

- llael Cox et al., “Land Use: A Powerful Determinant of Sustainable & Healthy Communities,” EPA, Progress report 4.1.2, 2013. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/fy13productnheerl4121land_use_synthesis.pdf.

- N. A. A. Valdeolmillos, R. Furlan, M. Tadi, B. R. Sinclair, and R. Awwaad, “Towards a knowledge-hub destination: analysis and recommendation for implementing TOD for Qatar national library metro station,” Environ Dev Sustain, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Patel and H. Ibrahim, “Environmental Sustainability Comparative Assessment of Low-Rise and High-Rise Neighbourhoods based on People’s Lifestyle Preferences: The Case of Doha, Qatar,” presented at the The 2nd International Conference on Civil Infrastructure and Construction, Feb. 2023, pp. 978–987. [CrossRef]

| Area | Purpose | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Lusail City - 38 km2 with 27 Km of Coastline | Mixed-use urban development | 2013 [18] |

| The Pearl – 4 km2 with 32 Km of Coastline | Mixed-use urban development | 2004 [19] |

| Katara – 0.038 4 km2 with 1.5 Km of Coastline | Cultural Centre + Park + Retail | 2010 |

| West Bay - 20 km2 with 3.5 Km of Coastline | Central business district | 1974 [20] |

| Museum of Islamic Arts – 0.29 km2 with 1.5 Km of Coastline | Museum and public park | 2008 |

| Hamad International Airport - 22 km2 | Airport and related facility | 2014 [21] |

| Doha Port / Mina District – 1.5 km2 | Mixed Use District (Land reclaimed and used as Port prior to regeneration into Port district) | 2022 |

| Study Title | Citation | Key Focus | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developing Sustainability Index Measurement for Reclamation Area | [31] | Coastal resource, Building and Infrastructure | Evaluation Index System |

| Model of Sustainable Urban Infrastructure at Coastal Reclamation of North Jakarta | [32] | Land use, Transportation, Building, Open Space, Infrastructure Network, Energy | Structural Equation Modelling |

| Circles of Coastal Sustainability: A Framework for Coastal Management | [33] | Coastal Boundaries, Human well-being, Socio-ecological systems | Gap analysis of existing frameworks |

| Long-term monitoring and evaluating of land development in reclamation area under rapid urbanization: A case study in Qiantang New District, China | [34] | Land use/ land cover | Land change detection using LANDSTAT |

| Framework for measuring sustainability of neighbourhoods in Nagpur, India | [35] | Land use mix, population density, open space ratio, access to amenities, road network | Indexing the benchmarks |

| Environmental | Spatial – Urban Planning | Socio-Economic |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).