1. Introduction

The world over, non-inclusive interpretations of the archaeological heritage affect the inventory, management philosophy, approaches, and presentations of the past. It should not come as a surprise that by-passing indigenous communities, would often lead to inaccuracies, omissions, and misrepresentations of their past. For this study, the key question was how much of the current South African heritage identification, interpretation, grading, classification, and management would change with input from indigenous people? Is the notion of indigenous voices a fancy notion that has no practical usage in heritage management? These are more than curious questions but ones that also speak to the bigger debates about decoloniality in much of southern Africa [

1,

2]. This paper incorporates indigenous perspectives of heritage management as a decolonial approach of heritage and archaeology; disciplines that remain etched in foreign (Western) concepts [

3]. Western notions of heritage are far from being monolithic but versions that introduced these disciplines in Africa seem to be too reliant on tangible heritage, while being underequipped to deal with intangible African elements. In this paper, we contend that the intangible and tangible heritage are entangled in a web of relationships that make it difficult to split hairs.

African forms of heritage are woven into the fabric of indigenous knowledge systems that store and communicate the past through media such as names, songs, poems, totemism, rituals/taboos, storytelling, landscape/memory mapping, folklore, traditional rites, heroism, sacrifices, negotiations, and games, among others [

4]. While many of these do have some form of physical representation, a cursory approach only restricts the observer to superficial references while missing the deep-seated meaning of diverse indigenous African heritage. For instance, the wealth of information buried in African names and how these contrast with the diluting-effect of foreign names has rarely been explored [

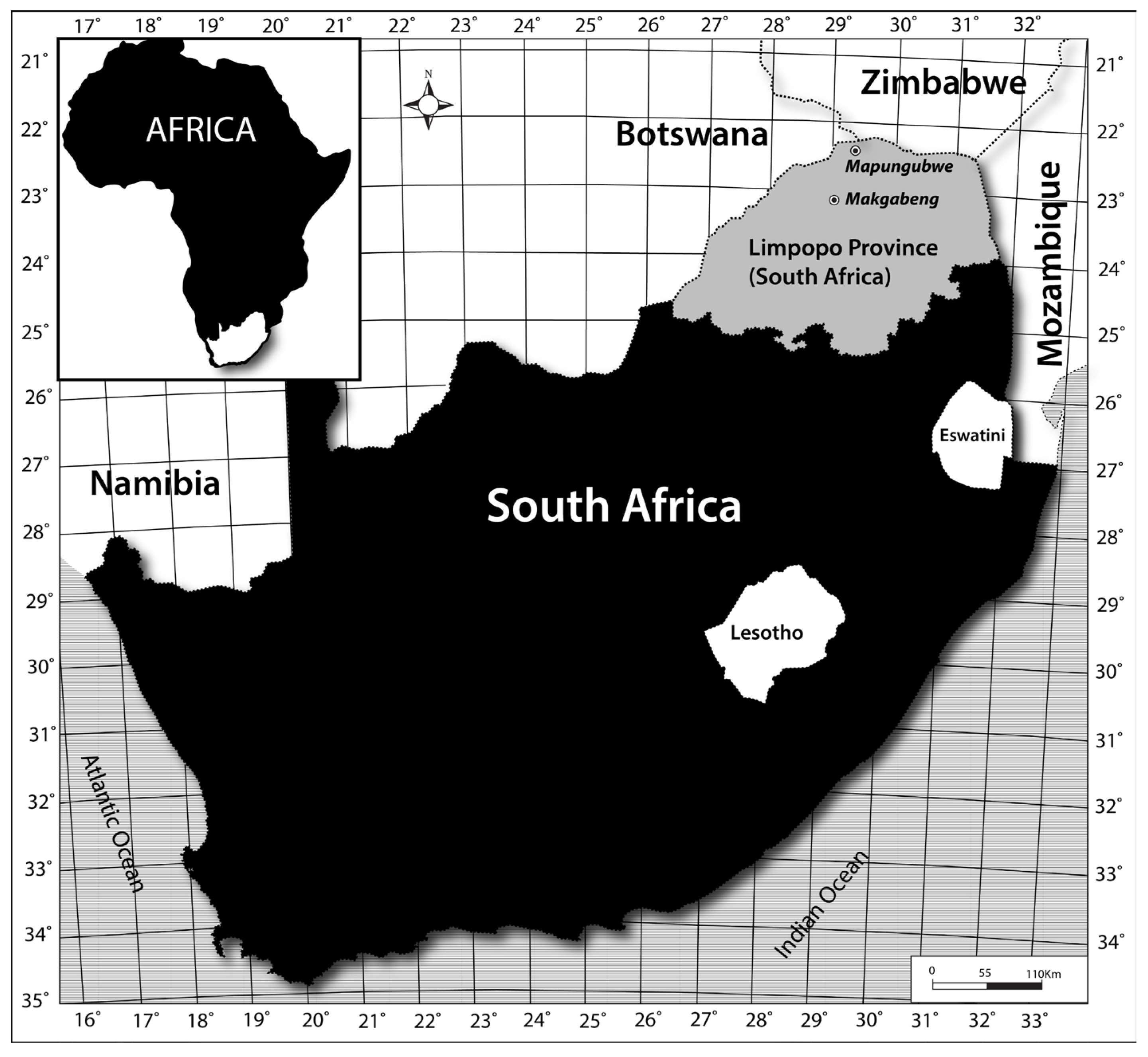

5]. This paper explores how indigenous perspectives of heritage practice can enhance our understanding and management of cultural heritage within the Mapungubwe and Makgabeng Cultural landscapes in South Africa (

Figure 1).

This work applies to the wider region and the 1884 Berlin-Conference drawn national boundaries carry no other significance, beyond the intended alienation of people and culture. South Africa was also chosen as a country with one of the longest recorded history of archaeological research on the subcontinent. Yet, despite the years of research and professional heritage management in South Africa, many questions still linger. For instance, in the absence of indigenous input, should etic heritage identification and management be conclusive or tentative? Can heritage be fully comprehended without indigenous input? The current paper attempts to explore these issues while marrying them with systems of collective memory and memory-making, as key concepts that illuminate each other.

Throughout the world, the initial exportation and imposition of Western style of heritage management has resulted in the exclusion of indigenous people from the practice and their dispossession of ancestral land, on which much of the heritage is located. South Africa is no exception [

3]. Archaeology was conceived at the height of prejudiced European colonial expansion, making it easier to overlook local African expressions while imposing foreign views and methods [

5,

6]. Parallel colonial processes also alienated most indigenous people from their heritage leading to the near total loss and disconnection between Africans and their memorialization activities [

7]. Many scholars during the colonial and apartheid eras discarded local knowledge, oral histories, living history and even early ethnological records that had potential to illuminate the history of the Mapungubwe Cultural landscape [

8]. A preservationist approach in which local people were perceived as a threat to their own heritage, also reinforced the alienation of indigenous communities and their past. The freezing effect of this conservationist approach limits indigenous engagement while commodifying heritage for elite consumption [

3,

9]. The initial creation of the Mapungubwe and Makgabeng cultural landscapes can be understood in this purview [

10,

11,

12]. The question that still begs an answer is how much was lost, missed, or even misidentified because of lack of indigenous input? [

13]. This is what we attempt to answer in this study.

The shackles of Western style heritage management are reinforced by World Heritage Site management systems [

3]. For instance, Palestinians in the occupied Gaza and West Bank areas in Israel cannot participate fully at the world heritage stage because they do not constitute a state [

3]. In South Africa, the Mapungubwe World Heritage Site was inscribed in 2003 without the involvement of indigenous people, who had earlier been forcibly removed to make way for the creation of the conservation area and National Park [

2,

7]. Even though the inscription of Mapungubwe was done almost a decade after the demise of the apartheid regime, its mapping and nomination were conducted by researchers and SANParks officials, thereby creating a knowledge gap.

Nationally, the South African World Heritage list is also very telling, because it is heavily dominated by Western-style monumental properties [

9], p. 272, [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Western heritage is often skewed in favor of fancy objects of knowledge and aesthetic pleasure that are endowed with historic artistic as well as economic values at the expense of others [

18], p. 82. This focus is detrimental to indigenous heritage that focus on ritual and spiritual engagements [

1,

19].

Throughout the world, many researchers have called for the involvement of indigenous communities in matters of heritage, mostly as part of decolonial approaches, but few have delved into the mechanism of how such communities create and connect to their common heritage [

20,

21]. Some archaeologists have made efforts to include indigenous perspectives with archaeological practice and interpretation for instance [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Their efforts opened for participation of native Americans and first nations people in the process of archaeology and heritage management. This is seen a crucial step in helping archaeology move beyond the legacy of colonialism by ensuring meaningful and satisfying participation of descendant communities [

31]. However, South Africa is still lagging in this regard [

10,

11,

12], compared to countries such as the USA, Canada and Australia where some progress have been made [

31]. Although remarkable efforts were made, the appropriation, commodification and inappropriate use of objects, images and information relating to artifacts, sites, rock art and other iconography is still a great concern to indigenous people in America and it is also true for South Africa [

1,

31]. This study attempts to increase the scope of archaeology and heritage management by incorporating indigenous perspectives.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study deals with the management practices and engagements in deep-time archaeological heritage of the Mapungubwe and Makgabeng cultural landscapes in northern South Africa. The former (Mapungubwe) is located on the confluence of Shashe and Limpopo rivers on the South African’s northern border with Botswana and Zimbabwe. The landscape is archaeologically famous for the Mapungubwe site, a National and World Heritage estate that occurs within the Mapungubwe National Park. The site is centered around the Mapungubwe Hill and its immediate areas in the valley [

19,

32]. In 1922 the area was made a part of the nine farms of the Dongola Botanical Reserve [

33]. This was later, turned into the Dongola Wildlife Sanctuary in 1947, only to be de-proclaimed when Prime Minister Jan Smuts’ term of office ended [

33]. Decades later Vhembe Game Reserve was established on the same footprint before it was renamed Vhembe-Dongola National Park in 1998. The name changes continued and on 24 September 2004, Mapungubwe National Park was declared, following the 2002 proclamation of Mapungubwe archaeological site as a National Heritage estate and its inscription on the World Heritage List in 2003 [

34]. Significantly, at no stage were the needs of indigenous communities considered [

10,

17]. Thus, its management falls under the South African National Parks (SANParks), South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) and the Department of Environmental Affairs which manages World Heritage Sites in South Africa.

The archaeology within the Mapungubwe park goes back more than a million years ago when Early Stone Age people and their Middle Stone Age and Later Stone Age successors left lithics, bone tools and Rock Art on the landscape [

35,

36]. Ancestors of the Late Stone Age producers shared the landscape and probably assimilated into the Iron Age farmers starting around 900 CE [

37]. It was not until the turn of the Second Millennium CE that early signs of state formation were noted and peaked at Mapungubwe from 1220 to 1290 CE. By this time, Mapungubwe was the center of one of the most powerful indigenous kingdoms in Southern Africa [

38,

39]. After the collapse of Mapungubwe, life continued in the cultural landscape and today we have several Venda (Tshivhula, VhaNgona), Sotho-Tswana (Machete and Sematla) and Lemba groups who claim connection with the landscape and have been formally recognized by SANParks as descendent communities. A few members of the Machete and Sematla people have successful claimed portions of their land, while other claims are still unresolved.

The Makgabeng plateau (

Figure 1) is located on the western end of the Soutpansberg Mountain Range, southwest of Mapungubwe. The area is approximately 225 km

2 and has interesting geological phenomena with aeolian sediments dated around 2000 million years [

40]. It was originally inhabited by the Stone Age before the arrival of Iron Age communities around CE 700 [

41]. Later Iron Age groups such as the Venda and Sotho-Tswana groups moved into area starting around 1200 CE and began creating ‘farmer’ paintings (Northern Sotho rock art). The BaHanawa groups (Sotho-Tswana) who dominated the plateau, trace their roots to the same times [

41]. Despite the recent (2019) National Heritage status application, Makgabeng remains ungraded. The threat of platinum mining encroaching towards the invaluable heritage led to the provisional protection of the Makgabeng Plateau while the application for grading is in progress. It is important to note that the Makgabeng Plateau has an important layer of significance as a UNESCO protected biosphere reserve.

The study sort to explore collective memory and indigenous perspectives of heritage management using case studies from these two areas. Case studies are intensive in-depth research of a specific individuals, contexts, or situations [

42,

43,

44]. They offer a practical method to the decolonial studies and diachronic pursuits that both Mapungubwe and Makgabeng Cultural landscapes afford [

10,

11,

12].

Our methodology involved designing an interview guide, qualitative data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of outcomes. The interview guide, translated from English to two languages (SePedi and TshiVenda), briefly described the research purpose and parameters for voluntary participation. We used semi-structured open-ended questions that allow researchers to pursue key issues while gleaning additional relevant information that may not have been envisaged [

45]. The study also gleaned data from published literature, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), as well as hermeneutic phenomena. Hermeneutic phenomena simply mean researchers’ attempts to explore issues based on their lived experiences [

46]. Our lived experiences relate to the Tsonga speaking groups of Chauke and Hobyane, that occur in the Hlengwe valley in southern Zimbabwe.

The study participants are categorized into two broad categories; indigenous communities and heritage practitioners employed by SANParks and Blouberg Local Municipality. Participation in this study was fully voluntary. About 68% (n=42) of the participants came from the Makgabeng and 32% (n=20) came from the Mapungubwe. As participation was voluntary, the sample size could not be expanded further but when calibrated with hermeneutic phenomena, the data obtained was sufficiently representative of broader perspectives. The study used purposive sampling to select participants [

47]. Key interviewee strata included age, knowledge of the subject matter, expertise, and membership of existing registered community forum groups for Mapungubwe [

10,

11,

44,

48]. The participants were all elderly (between 50 and 80 years of age). The choice of the age range was informed by our desire to interact with respondents from the villages that are experienced and have sound knowledge of cultural heritage and its management.

Interviews with registered descendant communities in the Mapungubwe Park Forum was organized with the help of SANParks heritage practitioners who are familiar with their protocols [

10]. Interviews and FGDs in the Makgabeng Cultural Landscape were organized through a key informants Felix Mosebedi (local resident) and Nguako Jonas Tlouama (tourism officer for Blouberg Local Municipality). Felix also assisted our seSotho translator (Lesiba Phahladira) during the interviews. Our choice of respondents grew from the snowballing process in which next interviewees were identified with the help of previous ones. Two FGDs were held in the Makgabeng, one in each of the two villages (New Jerusalema and Thabanantlana) and two FGDs were conducted in the Mapungubwe, as well as one FGD with the four heritage practitioners at SANParks.

All interview and FGDs questions related to (i) identification of heritage sites (ii) interpretation of heritage sites (iii) evaluation/ grading of heritage (iv) presentation (v) preservation, (vi) heritage management (vii) heritage legislation opinions (viii) role ascribed to descendant communities in the management of heritage, among other topics such as tourism emanating from these discussions. Recorded interviews were transcribed and analyzed using thematic content analysis [

49]. Thematic analysis of data involved crafting a valid argument out of the patterns and themes emerging from the study [

50]. Common themes emerging from the sorted data were coded upon completion of data transcription. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Witwatersrand, South Africa.

3. Results

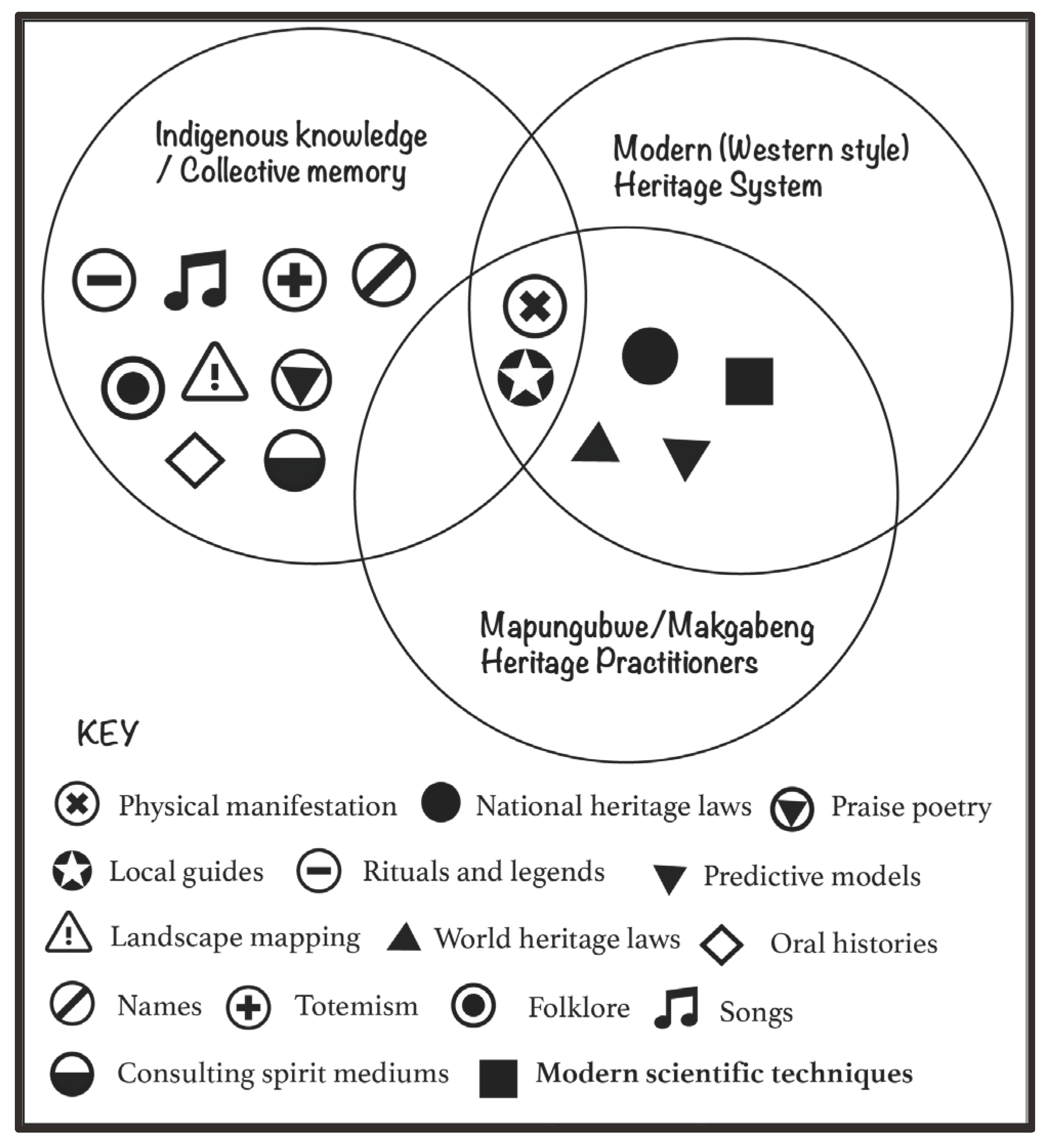

Here we present indigenous people’s perspectives of identifying, interpreting, evaluating, and managing of heritage, and how these views intersect (or not), with modern practice. We have not disclosed participants’ personal information according to their requests. The study found that indigenous knowledge systems that are entrenched in collective memory rely on intergenerational proxies for heritage identification and management; such as physical manifestation, naming system, consulting spirit mediums, genealogies/ praise poetry, oral histories, legends and landscape mapping/memory. Finding from heritage practitioners show very limited overlap with indigenous perspectives.

Physical Manifestations

All indigenous community participants stated that physical manifestations are infallible proxies for identification, interpretation and evaluation of some components of heritage. One participant in particular (a 54-year-old Sotho-speaking man from Mapungubwe forum group of Machete), went on to elaborate in almost textbook fashion that; “Items that demonstrate that it is a site are some of the potsherds, grave markers, and evidence of the presence of old structure of buildings. Even cattle kraals endure for a long time otherwise 1000 years, there would be cattle dung, cattle kraal will be big rounded or circled and the trees and grass does grow inside”.

One would be forgiven for thinking that above statement is an extract from an archaeology textbook, but as people who grew up in rural settling, the current authors we can confirm that this is common knowledge. As stated by all indigenous participants, daily chores that took place away from modern settlement precincts; such as traversing through the cultural landscape, herding livestock, fetching firewood, gathering berries and medicines, etc, often resulted in eye-catching finds such as those described above. As one Sotho participant (male aged 61 years) from Sematla put it, “it is not only what you see at this sites, but also what you don’t see, such as plastic, written glass and metal cans, that tell you that you are looking at an old place from deep time”. In Makgabeng, indigenous participants noted that because rock art has not been practiced in recent memory, so when they encounter it, they immediately know this is old manifestations of culture. Physical features are obvious and easier to identity but the reading of time, along with the interpretation based solely on the physical characteristics are less palpable. One male participant from New Jerusalema, in Makgabeng aged 78 years said “we can see that this was a big homestead for a polygamous traditional healer, or chief by the location of the site and layout of the remains of structures”.

Encounters of human activities away from modern habitation spaces always attracts the attention of indigenous communities, as stated by one Sotho participant from Sematla (Mapungubwe forum group) aged 78 “all abandoned homes such as Mapungubwe, are still the abode of the homeowners’ spirits and their ancestors”. Thus, physical manifestations are inadvertent pointers to heritage. They show indigenous people places to respect and avoid if they do not have families ties to them or when it is not the right season or time to approach such sites.

Heritage practitioners, on their part, concur with the scientific disciplinary tenets in which physical features are the chief method of identifying, evaluating and managing archaeological sites. Where they differed with indigenous participants is the interpretation and evaluation of heritage because to the latter, physical manifestations are best known through the relationships handed down memory lane.

Rituals, Legends and Oral Histories

A Sotho female participant aged 81 years from the Makgabeng (Thabanantlana) said “We know these sites because we grew up going there to perform rituals with our family members and we share this information with our children”. This type of heritage is not easily deciphered by outsiders. A male (Sotho) participant aged 56 years from Sematla claimed that SANParks employees “destroyed the grave of Mosiri because they did not know the site. I learnt our history from our elders who shared it with us in order to know who and who was living there from our clan. For instance, at the confluence on a site I knew that there is a grave of one of our ancestors (Mosiri) which they destroyed while building a road”. He also stated that after someone has been buried, the dead person’s spirit hovers over the grave until a ritual is done to transferred his/her spirit onto a shrub which is then dragged and planted in the homestead. He continued to explain that, if a stranger sees the shrub, they might think that it is just flowers, but “this shrub is for my father, we took his sprit to guard us here at the home”. This transaction “literally” transplants significance and focus away from the grave to the shrub but archaeologists would not be able to connect the dots easily. The participant also noted that for some communities or some important family members, graves remain as the focus for rituals and libations, without any transfer of the spirit to the shrubs.

Significantly, all the indigenous participants affirmed that when it comes to physical manifestations of heritage, the size of the site or feature does not necessarily translate to higher significance because “it is the king that makes a place a palace, and not vice versa”, said one Venda female interviewee (81 year old) from the Tshivhula. She also said sites become important because of their spiritual significance. As one male Sotho participant from Mapungubwe forum group of aged 78 explained, the “discovery” of Mapungubwe through the local guide owes much to the place’s spiritual significance than physical manifestations because “even today there are no major features and structures that sets this hill apart from the surrounding ones, but because our ancestors revered the hill because of supernatural sounds, such as the bellowing animals, the beating of drum and ululations that were constantly heard, the local informant exposed this hidden hill where archaeologists have now excavated deep middens. The name says it, it is the hill of bellowing jackals not a hill of kings. Do you think the archaeologists would have found it by looking for potsherds? It was my uncle Mokwena who showed Mapungubwe Hill to the settler farmers.”

Even in the Makgabeng Plateau, some rock art sites were also discovered with the help of local people who were taught by their forefathers not to temper with this art because ancestors will be angry. One Sotho male participant aged 66 from Makgabeng (Thabanantlana Village) explicitly noted that; “We tell our children not to touch the painting or to pick anything from the site or to play at the sites because ancestors may be angry. There are things that you must not do at a sacred site otherwise if ancestors get angry you will bear the consequences”. Information about important sites is shared communally and it is every household’s responsibility to teach their children about sacred places because often the negative consequences of desecration, such as lack of rain, are collectively experienced. Participants at the Thabanantlana FGD expressed that there are places they were told not to go without being sanctioned by the local custodians; “Just behind the mountains, we sometimes see visitors go there but we know that it’s the most important site because it involves chiefs and the history of the Makgabeng area. If you go alone, you might end up being in danger because you might end up going where you’re not supposed to. We understand that they are all important, so we protect all of them equally and advise children not to ruin them”.

Oral histories sometimes retain fine grained details that archaeology cannot fully explore. A Venda male participant from Tshivhula (Mapungubwe forum group) aged 58 stated that outsiders cannot fully comprehend this landscape without inquiring from the local people. To explain the generally low number of archaeological house remains today on the landscape, he recounted his ancestors used to build houses with wooden poles placed directly on top of rock outcrops, without needing and indeed leaving no major foundations or debris for archaeologists to see. He explained that “We were told, that the hill has a stone, sand stone. Since they (sandstone) are fragile or soft rock from sand and you can change it to any shape that you feel like because if you use iron tools you can chip it up to tip like this then you can just make a circle chipping it then you put poles right round and you plaster it with mud then you make a roof then it’s done.

Additionally, details about games and other props would not be easily deciphered from physical features alone. In the Mapungubwe cultural landscape and beyond, the Morabaraba (an indigenous game placed on groves on rock surfaces or curved on wooden pieces) was popular. The game is still a popular among the local communities. A male (Venda) participant from Tsivhula (Mapungubwe forum group) aged 56 said the knowledge and skills of the game (Morabaraba) was passed on from generation to generation.

Names

The system of naming things, places and people is also a heritage identification tool. We have already shown how participants linked the name Mapungubwe to the site’s legendary survival until the 20th century “rediscovery”. Other layers of Mapungubwe’s heritage also lie hidden in local names. For instance, the a Sotho male participant at the FGDs at Mapungubwe exposed the presence of sacred places next to Mapungubwe; “

When we come to Nyende is the one that was used by rain makers. (Nyende means place of more water in Kalanga).

They don’t do it straight at Mapungubwe. They do it at Nyende which is western Shona (Kalanga). That’s why every time when we talk, we talk of Kalanga people. If you listen to the names of places around here Mapungubwe they are from western Shona and Tswana or Sotho (Tswana and Sotho, are very closely related).

You must respect the mountain (Nyende) too much. This mountain is the same as Guvade la Manakedi from Botswana. This is the hill of the ancestors that’s why I say the place of ancestors... Like where we are by now is Samabulane but Afrikaners called it Hamilton because there was Hamilton person who was occupying this place his full name is John Hamilton. Samaria, it falls under Danstart but it is not either those names because it’s called keLetshigili meaning long time there was waterhole in Sotho we call it (kelekopo) on a rock whereby that rockhole will be very deep and can last up until a year without water drying up. Animals will come and drink water and even people will take their cattle to drink water there. So there was this big snake by the name of (tharu) python to be the security …but people long back there they wanted to know why these elders always say they shouldn’t go there. They explained that there were about 10 boys who were cattle headers, and they went to the pool for the purpose of swimming then 9 of them were killed by that python then the one that survived ran back home to tell the elders that they were swimming in that pool then there was very big snake which killed others which they call it a monster (Letshigili that which has killed the kids)”. Clearly, these places are archaeologically unknown today. Earlier ethnographic work among the Venda had also noted Nyende (written as Nyindi in Venda and Nyete in Sotho) as a sacred hill but these revelations were ignored by archaeologists [

8].

Landscape Mapping

In recounting oral histories and praise poetry, one often hears physical landmarks such as hills, rivers and place names that almost form a mental map connecting to aspects of histories. In retelling the stories, a few details may shift but major landmarks tent to anchor the stories. A Sotho participant from Sematla (Mapungubwe forum group) aged 54 gave the following account; “Yes, we were told that we also have others from BaBirwa people also, but BaBirwa people are from Naring. Naring is not far from Phalaborwa then from Naring they have to go Nwala la mahutse kafi ya nuka ya loyi nuka ya loyi ke Limpopo. Then from there is when they moved or dispersed some because of the wars with Mzilikazi then some they went to Botswana some to Zimbabwe some the remains some the go back to the site of Phalaborwa”.

A (Sotho) male participants from Sematla aged 56 also mentioned that there are sacred pools which are associated with the Mapungubwe cultural landscape which are never mentioned by heritage managers and archaeologists;

Yes, there are pools which do not dry. There is the pool of Mambwe where mmba is a house, Mmbambwe is a house of stone. It’s a pool where the Limpopo and Shashe river meet where people of Botswana made a lodge now. We were told that someone can get inside water for seven to eight days and they say there is a house of stone. The person apparently inside the water will be doing rituals of Uthwasa. we don’t know on our culture about the person can do these rituals of uthwasa to someone it’s a new thing. What we know is that a person can stay on top of mountain for days while we don’t know where the person went and comes back as sangoma or enter inside the water and comes back as Sangoma. that’s where we say the person has calling from ancestors. Some of the pools are Mmbambwe, Masubelele, Masidopwe and Masivhundi. we have to respect and do not play at these pools. people get inside for the purpose of uthwasa and comes back sangoma and cleansing it’s happening around there. There is an old woman who was called Mangube. She will get inside with firewood and make fire inside the water and while people are looking with their own eyes to show that things were working in the past. She will make a fire and cook food and give people food to eat and were satisfied but now it is no longer happening because of people comes and bath just for the sake that it’s their homes and kills their gods (zwifho) because these things can count onto zwifho. things are not going well as the way it was supposed to be.

Consulting Spirit Mediums

The Sotho FGD participants from New Jerusalema (Makgabeng) stated that consulting spirit mediums is an integral part of their belief system. Spirit mediums also play a very important role in identification and interpretation of heritage sites which the living generation may not know. Participants stated that spirit mediums can lead to an unknown site and explain the circumstances of the site to the clan or family. Thus, “a spirit medium can dream and show you where your relative was murdered. This you know is true because the possessed medium speaks in the original languages of the clan, and they often refer to the history of the clan in praise poetry fashion”. In doing so, they may also mention indigenous place names which are forgotten or no longer official. For example, one Sotho participant from (Samaria) Mapungubwe aged 56 said: “We know our history through spirit mediums. Yes, in fact when we come to all these things, they connect a person who is Venda is from Shona because when a Venda get possessed, they speak ChiShona language so meaning that their roots are from Shona which they are from Monomutapa vhaTshaminuka … In the past we would go to consult with a spirit medium then the rituals for rain would be done under this Morula tree, with fires prepared right where the rocks are piled”.

Genealogy and Praise Poetry

With much of indigenous history unwritten, recounting of genealogies and praise poetry is a very rich way of delving into African heritage. The following interviewee (A Sotho 56 years old male from Machete) was even careful enough to note how the changes in the language (from Sotho to Kalanga) of his own praise poetry helps to connect the dots to his clan origins; “

I do. when we are like this we are known as Mirwa. Mirwa is a person given birth by Mukalanga (Kalanga western Shona) which were known in the past as Mambo and person called Mosotho. Mosotho can be Mokwena or Mohurutsi or Morolong or Bohlokwa but I come from Bakwena side. That’s why I praise myself as “Kgomotso is the child of Phalandwa” botshokwa is mixed with Kalanga and sotho.” I am Kgomotso. Kgomotso is the child of Phalandwa. Phalandwa is the child of Phalandwa and Phalandwa is from Salupa”immediately I talk about Salupa just know its Kalanga now no longer sotho to show that we are from Kalanga People then Salupa from Zengeni which is Kalanga then Zengeni who is Nteteleke which is Kalanga”. To their credit, archaeologists have attempted to connect the Shona migrations to this area using ceramic culture-histories [

39] and this new information on praise poetries strengthens the case.

This research has found that collective memory is at the centre indigenous heritage management practices. Heritage management skills are passed on from generation to generation orally. Involvement of indigenous communities in archaeology and heritage practices has huge potential in the management of cultural heritage.

4. Discussion

Using the case studies from northern South Africa and our own lived experiences, the present study explored whether indigenous voices are still relevant in the 21st century heritage practice. Given the long history of alienation of people from their past, as well as globalization and modernization, we wanted to test the hypothesis that indigenous people still hold heritage-altering information. To do this, we revisited indigenous processes of heritage production and how they compare to modern practice. The exemplary South African heritage legislation, as well as the management of one of South Africa’s pinnacles of archaeological heritage (Mapungubwe and Makgabeng) lends themselves to such a study.

Our interview results and literature survey reveal dichotomies between the Western state-based system and indigenous people’s heritage notions. The study revealed that other than physical manifestations of heritage sites, there are several indigenous ways of identifying, interpreting, and evaluating heritage sites. Collective memory and indigenous knowledge systems are at the center of these local ways of managing heritage. The knowledge and skills to manage heritage sites are shared from generation to generation through various forms such as physical manifestations, legends, oral histories, landscape mapping, names, songs, praise poetry and rituals. There is, however, very limited overlap with modern Western-style of heritage management (

Figure 2).

While modern practice is limited to physical manifestations, modern scientific techniques and models, it also makes use of local guides on limited occasions associated with initial identification of sites and tour guiding (

Figure 2). It is curious to note that after the local guides have pointed sites to archaeologists and heritage managers; their views and opinions about the interpretation and management of their past are often ignored. Thus, after the local informant (Mokwena) has pointed out Mapungubwe to the white farmers, we do not hear about him and his knowledge about sacred pools nearby also never makes it into the official record [

8]. In short, modern practice lack the tools to fully explore much of the intangible heritage and is prone to the unhelpful arrogance of learned practitioners who ignored indigenous help in locating and interpreting sites.

When compounded with the colonial displacements that left people in unfamiliar relationships, the arrogance of modern practice further negated learning opportunities by privileging current settlement and landownerships patterns over historical evictions. Thus, when Mapungubwe was being nominated, white farmers and mining companies who owned the land near the site were the key stakeholders in terms of the South African legislation and the 1972 World Heritage Convention [

3,

7]. Similarly, the Makgabeng communities are now associated (by proximity) with less familiar rock art heritage, making them stakeholders according to the South African heritage legislation. The archaeologists and heritage managers’ arrogance of not linking archaeological sites with specific clans only impoverishes the reader because indigenous voices adds so much to heritage management processes.

The study revealed that indigenous communities can identify, interpret, evaluate, and manage the broadest class of heritage, i.e., tangible and intangible heritage. Even in instance where indigenous people lack intimate knowledge about certain aspects of heritage, this study has shown the sensitivity of local African people to manifestations of heritage. For instance, the BaHananwa people in Makgabeng confirmed that they do not have clarity on the timing and authorship of most of the rock art sites in the plateau (having been told by the archaeologists about the art’s national importance) but still have systems in place for their traditional protection. Therefore, the Western thinking that local communities must be separated from heritage places to ensure the preservation of sites is misplaced.

Some of the indigenous components of heritage area too fine grained for national and international heritage practices such as the notion of Outstanding Universal Values (OUV) of World Heritage Sites. The BaHananwa ’s practice of transferring spirits of their deceased relatives from the grave site to a shrub that is then planted in the homestead, may not necessarily capture OUVs. A cursory assessment would then conclude that we do not lose much by ignoring (or inadvertently not consulting for) such types of heritage. However, if one is to learn from the Mapungubwe example, where the site survived as “clan memory and name” until its “rediscovery” with the help of clan-member’s guidance, about 700 years later. It is as if, the Mapungubwe OUV owes its discovery to the none-OUV heritage that surrounds the site and have elevated an otherwise obscure tapestry of the past because there are very few outstanding features on the sites, beyond the rich gold objects and other materials from archaeological excavations. As such Western science’s overreliance on one dimension of physical manifestations of heritage leaves much of both the tangible and intangible heritage unexplored.

There are challenges of site grading following formal ways because this omits spiritual significance which is the core of indigenous heritage. Much of indigenous African heritage come with family/clan/chiefdom/kingdom or regional relevance. Such hierarchies do not necessarily confer a higher grade. For instance, queen Nandi’s grave is important to the Zulu nation and to the immediate family. The site is a National Heritage Site and open to the public, against the wishes of the family [

51]. In this case, the grave’s national (Zulu) significance does not trump the family value. Indeed, in 2022 a group of celebrities in South Africa were chased away from the grave site when they entered the site without asking for permission from the family elders. It also matters who does the grading. Local community participants generally argued that grading of sites must be done by designated clan elders and spirit mediums in accordance with tradition. They argue that visitations to the sites must be sanctioned by indigenous people not SANParks officials. This tradition is also true for several other African communities in southern Africa [

1].

The other quandary of the South African three-tier grading system is its reliance on political boundaries. These boundaries often lake any historical alignment with cultural heritage. Political boundaries and the associated prejudiced policies of alienation, dissected cultures into fractions while combing others into “rainbow nations” that did not necessarily have historical connections. Accordingly, heritage experts may end up elevating sites of very little indigenous appreciation or relegating what local communities hold in highest regard. With relocations some surviving descendant communities simply cannot remember much about their original area [

52]. It is no wonder why the Makgabeng Plateau (with more than a thousand rock art sites and several Late Iron Age sites) has not yet been graded. By comparison Wonderwerk Cave in the Northern Cape is a Grade 1 heritage site based on a single rock art cave.

The omission of communities in site nomination that has been witnessed at places such as Mapungubwe need not be cast stone. For their part, heritage experts at Mapungubwe have attempted involving sections of local communities as registered forum groups in terms of biodiversity conservation. The fact that the communities are recognized in terms of biodiversity, not heritage, leaves a lot to be desired. Such attempts have been done successfully in Australia Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park where heritage sites that were already recognized for their tangible heritage were re-assessed to incorporate social values previously overlooked [

53].

The management system in South Africa still needs to be transformed to meet the needs of indigenous people. The use of indigenous knowledge systems has contributed significantly to the management of Tsodilo Hills in Botswana [

54] and the Clanwilliam Living Landscape in Western Cape of South Africa [

21]. In this regard, inclusion of collective memory and indigenous knowledge system have a huge potential to contribute to a broader understanding of indigenous heritage and heritage management.

Similar misunderstanding of intangible heritage also occurred at Njelele, a sacred site in Zimbabwe where ICOMOS refused to include it as part of the nomination of the Matobo Cultural Landscape [

55,

56]. The failure to recognize both sites on the same landscape meant that the rock art found within the Matobo was of far greater value to the world than the rituals and religious values of Njelele, which was considered by some experts as a pagan site.

This paper opened with a question on the implications of inclusion of indigenous voices in South African heritage. Our indigenous participants from Mapungubwe lamented that the presentation of the site leaves out some important sites and features which are linked to the landscape. There are sacred pools in the Limpopo River which are important to the indigenous people such as the Sematla. They also lamented that even the cultural significance of wildlife and geographical features are not presented to the visitors. A quick review of information pamphlets at the Mapungubwe Museum confirmed that wildlife and vegetation are presented from a biological perspective using Latin terms. With indigenous landscape mapping, local communities clearly have significant input in heritage identification.

While identification and management of tangible heritage has gained remarkable consideration, management of intangible heritage has been lagging [

57]. It has taken SAHRA and stakeholders long to develop mechanisms to promote and enforce the inclusion of intangible heritage in the management of heritage in South Africa. It is evident that intangible heritage cannot be promoted without inclusion of indigenous people in the identification, interpretation, and management of cultural heritage. At national level, the lack of community participation for most places is exacerbated by the fact that the Provincial Heritage Resources Agencies (PHRAs) and Local heritage offices which are supposed to spearhead this process are nonfunctional [

58].

5. Conclusions

A review of the literature suggests that although the academic literature of decolonizing heritage management is growing, there is a notable gap in understanding how collective memory and indigenous knowledge can be linked with heritage management planning to enhance heritage conservation. Colonial and apartheid, as well as post-apartheid heritage legislation has not paid much attention to indigenous input in heritage management but instead fragmented, antagonized, and alienated communities from their past. Using a qualitative research methodology, 62 individuals from the Mapungubwe and Makgabeng cultural landscapes were interviewed for their views on heritage identification, evaluation, management, and presentation. The study exposed that the legacy of mistrust between heritage professionals and indigenous communities has further stifled the sharing knowledge and impoverished the reader [

10,

11]. Accordingly, South African heritage remains overwhelmingly biased towards the tangible heritage. Heeding the calls for indigenous perspectives on heritage and its management, would alter much of this imbalance and even strengthen the standing of some tangible heritage. Indeed, acknowledging spiritually significant pools and names around Mapungubwe can only bolster the site’s significance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.; methodology, T.M. and F.B.; validation, T.M. and F.B.; formal analysis, T.M. and F.B.; investigation, T.M. and F.B..; resources, T.M.; data curation, T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M. and F.B.; writing—review and editing, T.M. and F.B.; visualization, F.B.; funding acquisition, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National-Research-Foundation-(NRF), Grant number 0000-0002-0722-2779.

Data Availability Statement

No other publicly available data beyond the published literature already cited. Original recordings and photographs collected during work remain in custody of the first author (T.M.).

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely thankful to the Mapungubwe and Makgabeng communities who participated in our interviews and Focus Group Discussions (FGD). They allowed us to tap in their wealth of knowledge which formed the basis of this paper. We are grateful to the South African National Parks (SANParks) and Blouberg Local Municipality for giving us permission to conduct this study with their registered park forum groups, descendant communities, and local communities. We also thank Felix Mosebedi and Lesiba Phahladira for assisting us with translations from SeSotho and TshiVenda to English and transcribing the recorded interviews. We also thank Nguako Jonas Tlouama (tourism officer for Blouberg Local Municipality) for facilitating our meetings with the Makgabeng communities. Our special thanks go to our key informant, facilitator, and participant, Chrispen Chauke (former SANParks Heritage officer) who unfortunately passed on before the completion of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ndlovu, N. Access to rock art sites: a right or qualification? South African Archaeological Bulletin 2009, 64, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. Decoloniality as the future of Africa. History Compass 2015, 13, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cesari, C. World Heritage and Mosaic Universalism: A View from Palestine. Journal of Social Archaeology 2010, 10, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pwiti, G.; Ndoro, W. The legacy of colonialism; perceptions of the cultural heritage in southern Africa with specific reference to Zimbabwe. African Archaeological Review 1999, 16, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B. Historical geographies of place naming: Colonial practices and beyond. Geography Compass 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S. Can archaeology help decolonize the way institutions think? How community-based research is transforming the archaeology training toolbox and helping to transform institutions. Archaeologies 2019, 15, 514–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuku Van Damme, L.S.; Meskell, L. Producing conservation and community in South Africa. Ethics Place and Environment (Ethics, Place & Environment (Merged with Philosophy and Geography) 2009, 12, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiley-Nel, S.L. Past imperfect: the contested early history of the Mapungubwe archive. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taruvinga, P. Stakeholders, Conservation and Socio-economic Development: the case of Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape World Heritage Site, South Africa. PhD Thesis, University of Cape town, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shabalala, L.P.; Simatele, M.D. Perspectives on the Identification and Preservation of Cultural Heritage Tourism Products and Services in South Africa: Case Study of Mapungubwe and Barberton Makhonjwa Mountains World Heritage Sites. In Value of Heritage.

- Mlilo, T. Seeking inclusive heritage management approaches in South Africa: The case of Mapungubwe and the Makgabeng Cultural landscapes. South African Archaeological Bulletin 2023, 78, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Larrain, A.; McCall, M.K. Participatory mapping and participatory GIS for historical and archaeological landscape studies: A critical review. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 2019, 26, 643–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. Western hegemony in archaeological heritage management. History and Anthropology 1991, 5, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleere, H. The uneasy bedfellows: Universality and cultural heritage. In Destruction and Conservation of Cultural Property; Layton, R., Stone, P., Thomas, J., Eds.; Routledge: London and New York, 2001; pp. 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Labadi, S. Representations of the nation and cultural diversity in discourses on world heritage. Journal of Social Archaeology 2007, 7, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, L. The Nature of Heritage: The New South Africa. Wiley Blackwell: Malden, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choay, F. The Invention of the Historic Monument. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage. Routledge: London, United Kingdom, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, J. Through Wary Eyes: Indigenous Perspectives on Archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology 2005, 34, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkington, J.P. Clanwilliam Living Landscape Project. Nordski Museologi 1999, 1, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, G.P.; Andrews, T.D. (Eds.) Indigenous archaeology in the postmodern world. In At a crossroads: archaeologists and First Peoples in Canada; Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University: Burnaby, BC, USA, 1997; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dongoske, K.E.; Aldenderfer, M.; Doehner, K. (Eds.) Working together: Native Americans & archaeologists. Society for American Archaeology: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, T.J.; Colwell-Chanthaphonh, C. History is in the land: multivocal tribal traditions in Arizona’s San Pedro Valley. University of Arizona Press: Tucson, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kerber, J.E. (Ed.) Cross-cultural collaboration: Native peoples and archaeology in the northeastern United States. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, C.; Ferguson, T.J. (Eds.) Collaboration in archaeological practice: engaging descendent communities. AltaMira Press: Lanham, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Silliman, S. (Ed.) Collaborating at the trowel’s edge: teaching and learning in indigenous archaeology. Amerind Studies in Archaeology, University of Arizona Press: Tucson, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.; Wobst, H.M. (Eds.) Indigenous archaeologies: decolonizing theory and practice. Routledge: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, C.; Allen, H. (Eds.) Bridging the divide: indigenous communities and archaeology into the 21st century. Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bruchac, M.M.; Hart, S.M.; Wobst, H.M. (Eds.) Indigenous archaeologies: a reader on decolonization. Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, J.; Nicholas, G.P. Indigenous archaeologies: North American perspective. Global Encyclopedia of Archaeology. Springer: New York, 2014; pp. 3794–3803. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, T.N. Mapungubwe: Ancient African Civilisation on the Limpopo. Wits University Press: Johanesburg, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, J. Mapungubwe: an historical and contemporary analysis of a World Heritage cultural landscape. Koedoe 2006, 49, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SANParks. State of Conservation Report for the Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape World Heritage Site. Unpublished SOC Report Submitted to World Heritage Committee by Government of South Africa, Department of Environmental Affairs, South Africa, 2013.

- Hall, S.; Smith, B. Empowering places: Rock shelters and ritual control in farmer–forager interactions in the Northern Province, South Africa. South African Archaeological Society. Goodwin Series 2000, 8, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollarolo, L.; Kuman, K. Field and Technical Report: Excavation at Kudu Koppie Site, Limpopo Province, South Africa. South African Archaeological Bulletin 2009, 64, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, T.N. Debating Great Zimbabwe. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 2011, 66, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Manyanga, M. Resilient Landscapes: Socio-environmental Dynamics in the Shashi-Limpopo Basin, Southern Zimbabwe c.AD 800 to the Present. Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University: Uppsala, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, T.N. Handbook to the Iron Age: the archaeology of pre-colonial farming societies in southern Africa. University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, P.G.; Simpson, E.L.; Eriksson, K.A.; Bumby, A.J.; Steyn, G.L.; Sarkar, S. Muddy roll-up structures in siliciclastic interdune beds of the 1.8 Ga Waterberg Group, South Africa. Palaios 2000, 15, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; van Schalkwyk, J.A. The white camel of the Makgabeng. Journal of African History 2002, 43, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, N.; Beglar, D. Inside track: Writing dissertations and theses. Pearson Education. 2009.

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.e-book; Sage, CA, 2009; accessed 20 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Welman, C.; Kruger, F.; Mitchell, B. Research Methodology. Oxford University Press: Southern Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, T. The evolution of law enforcement attitude to recording custodial interviews. The journal of psychiatry and law 2010, 38, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M. Ciencia y arte en la metodología cualitativa, 2nd ed.Trilllas: México, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Radebe, N. Sustainable and inclusive community heritage tourism in the Makgabeng-Blouberg Region, Limpopo Province, South Africa. MSc Dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Burnard, P. A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today 1991, 11, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.; Norris, J.; White, D.; Moules, N. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily Sun, Nomuzamo Mbatha angers Shaka Zulu’s Family, 27 October 2022. https://www.snl24.com/dailysun/celebs/nomzamo-angers-shaka-zulus-family-20221027.

- Mudzamatira, W. The efficacy of cultural resources management in the Southern Gauteng Province, South Africa. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 2019, 74, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kasiannan, S. Cultural connections amidst heritage conundrums: A study of local Khmervalues overshadowed by tangible archaeological remains in the Angkor World Heritage Site. PhD Thesis, University of Sydney, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thebe, P. Intangible Heritage Management: Does World Heritage Listing Helps? In Proceedings of the Past to the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation, Proceedings of the Conservation Theme of the 5th World Archaeological Congress, Washington, DC, USA, 22–26 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Makuvaza, S. Why Njelele, a rainmaking shrine in the Matobo World Heritage Area, Zimbabwe, has not been proclaimed a national monument. Journal of Heritage Management 2008, 1, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ndoro, W.; Wijesuriya, G. Heritage Management and conservation from colonisation to globalisation. In Global Heritage A Reader (Kindle Version); Meskell, L., Ed.; John Willy and Song: Chichester, 2015; Chapter 6; pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Scheermeyer, C. A changing and challenging Landscape: Heritage Resources Management in South Africa. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 2005, 60, 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C.; Mofutsanyana, L.; Mlungana, N. A risk-based approach to heritage in South Africa. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and spatial information Sciences, 2019, Volume XLII-2/W15, 591-597. 27th CIPA, International Symposium “Documenting the past for a better future”, 1–5 September 2019, Ávila, Spain. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).