1. Introduction

Protected areas play an important role in conserving biodiversity, mitigating climate change, maintaining the health of human and natural environment and sustainable development. With the establishment of protected areas becoming an important indicator for the Aichi Biodiversity Targets [

1], the establishment of protected areas has become one of the top priorities of all countries in the world in the past few decades [

2]. According to the Protected Planet Report 2020, at least 22.5 million square kilometers (16.64%) of terrestrial and inland water ecosystems are in recorded nature reserves and protected areas around the globe [

3]. The establishment of protected areas has been effective in conserving wildlife resources and ensuring ecosystem integrity and stability.

While protected areas provide shelter for wildlife, curb biodiversity loss and provide new opportunities for a common global response to climate change, they are also places of conflict [

4,

5,

6]. The types of protected area conflicts, causes of conflicts, location of conflicts and management mode vary between developed and developing countries and depend on geographic location and specific socio-economic and cultural contexts. Protected area conflicts in developing countries are mainly driven by impacts on livelihoods, while protected area conflicts in developed countries are driven by social factors, including the emotional, recreational and cultural values that people attach to protected areas.

Although most of the benefits of establishing nature reserves are shared by the entire region and even the country, the costs of conservation are mostly borne by communities [

7] which creates great challenges for local community development and contributes to the continuous occurrence and evolution of conflicts. Since the establishment of the world’s first national park, Yellowstone National Park, in 1872, the subsequent establishment of protected areas has followed a traditional approach through a top-down exclusionary approach where local communities have little or no say in the establishment and management of protected areas [

8,

9]. The approach has led to hostile attitudes towards conservation strategies [

10,

11]. Meanwhile, due to the growing global population, the long-standing potential problems such as spatial area overlap and unclear land tenure between wildlife conservation areas and human community living spaces [

12,

13,

14] are constantly highlighted, and conflicts between nature reserves and neighboring communities are becoming increasingly intense. Community residents most rely on natural resources such as hunting, gathering, and fishing to maintain their basic needs, while the nature reserve administration usually restricts or prohibits these traditional ways of resource utilization, resulting in resource utilization conflicts, land tenure conflicts, development goal conflicts, and benefit distribution conflicts [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Conflict governance is not only a technical issue that needs to be addressed in the process of biodiversity conservation, but also a human development issue that is closely related to socio-economics. Fortunately, the conflict between conservation and development is increasingly being addressed, and natural resource management policies have shifted from a purely "conservationist approach" to more decentralized and participatory approaches [

20,

21,

22,

23]. These decentralized and participatory approaches incentivize local people to participate in and support conservation, and promote benefit sharing [

24,

25], aligning development needs with conservation objectives. In order to alleviate the contradiction between conservation and development, management authorities, NGOs and other social organizations have provided many development projects for communities, such as carrying out ecological conservation compensation, distributing production and living equipment that reduces environmental pollution, and volunteering to provide technical training for the development of community-based agriculture and forestry [

26,

27,

28], but the most ideal model is still eco-tourism [

29]. Although some scholars have argued that community co-management and other methods of involving communities in conservation and development have indeed strengthened the state’s control, distribution and management of resources, they have marginalized local communities and have not played a role in improving the livelihood capacity or well-being of local communities [

30]. However, a large number of studies have shown that the long-term and stable existence and development of protected areas must be supported by local residents, and the direct participation of neighboring communities in the establishment and management of protected areas as well as in conservation decision-making is more conducive to the development of protected areas [

31]. And most of the research with positive outcomes for well-being and conservation comes from situations where indigenous peoples and local communities play a central role [

32].

The effectiveness of governance depends to a large extent on the capacity and level of community participation, and the willingness to participate and behavioral response are its important characteristics. Residents of communities around protected areas are not only important participants in conflict management, but also the most important stakeholders [

33]. Their cognition, willingness and action are key factors influencing biodiversity conservation. Compared with passive participation in development projects, residents’ willingness to conserve and ecological conservation behaviors are more important factors influencing the resolution of conflicts between conservation and development. Previous studies have paid more attention to the role of funds, technology and resources provided by government agencies and environmental organizations in alleviating the conflicts between conservation sites and communities, and less attention to the subjective initiative of residents. In addition, the research on the factors influencing the willingness to protect and the behavior of conservation mainly used multiple regression analysis and analysis of variance (ANOVA), and took the personal characteristics of the residents and the characteristics of their families as the factors influencing the attitude to protect and the behavior of conservation, and found that the age, the level of education, the per capita income of the family, and the characteristics of the policy were the most significant influencing factors [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Previous studies have lacked the ability to synergistically analyze the influencing processes and mechanisms by putting together the community’s resource endowment, socio-economic conditions, conservation cost-benefits for relevant stakeholders, and residents’ protection cognition, willingness to participate, and behavioral responses.

Therefore, it is necessary to start from the community perspective to explore how residents’ protection cognition-willingness-action plays a role in solving the problems of conservation and community development in protected areas under different natural resource endowments and cost-benefit conditions brought by conservation. Our study focuses on the role played by community residents in conflict governance and analyzes the mechanisms and effects of subjective community participation in conflict resolution. It focuses on how natural resource endowment, conservation benefits and costs affect their protection cognition, willingness and actions, in order to explore the effective governance of conservancy-community conflicts. Based on this, the study takes Mikumi-Selous region in Tanzania as the study area, selects communities that are seriously affected by conflicts, and conducts semi-structured interviews with local conservancy managers and residents, with the main focus on addressing the following questions: (1) the current status of conflicts between natural reserve and neighboring communities in Mikumi-Selous region in Tanzania. (2) identifying factors that affect residents’ protection willingness and actions. (3) what relationships exist between community residents’ cognition, willingness and action towards conservation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

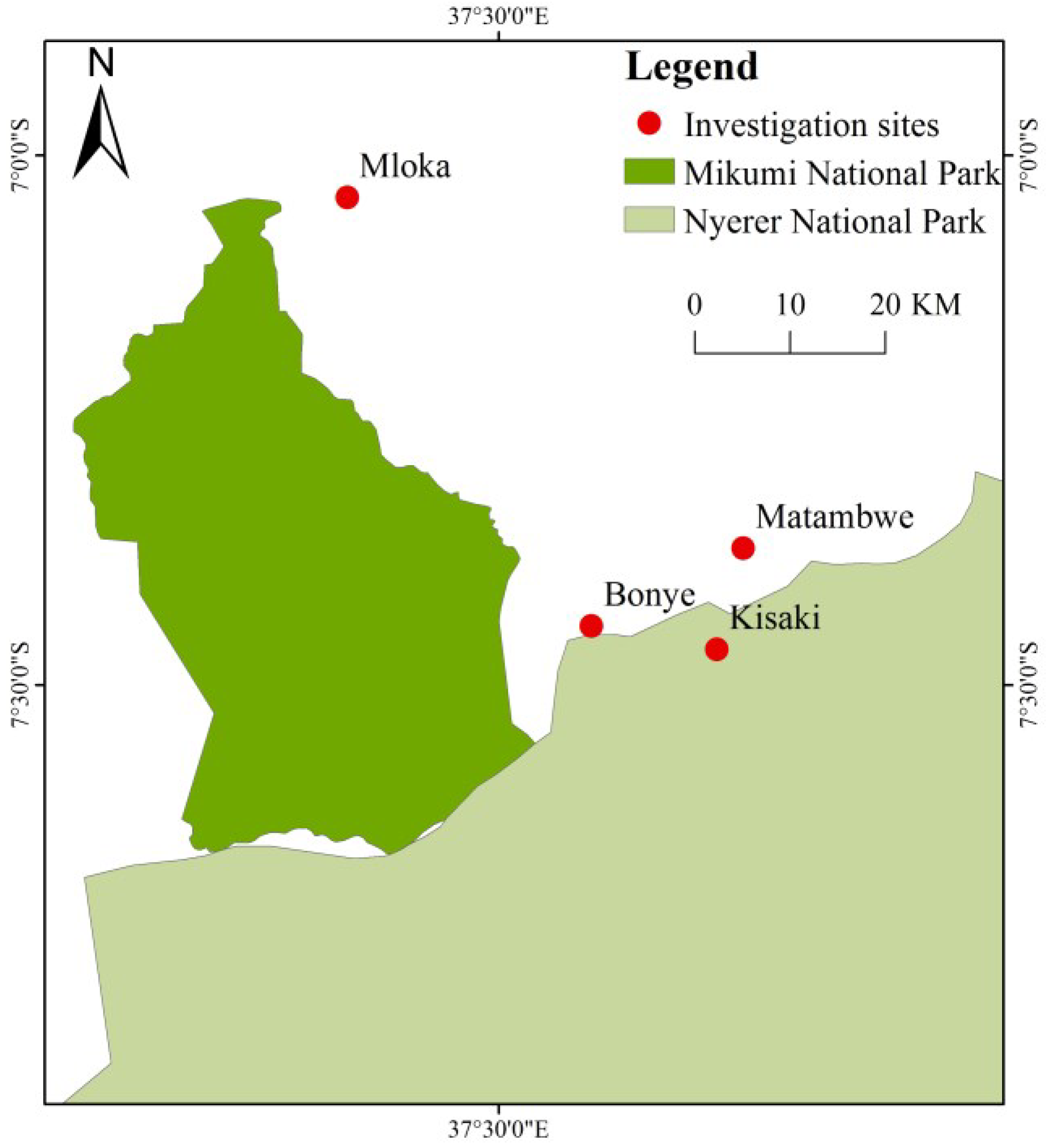

In this paper, Tanzania, Africa’s nature reserves were selected as the study area. The Mikumi-Selous region of Tanzania is an area with a concentration of nature reserves, where Mikumi National Park, Nyerere National Park and Selous Sanctuary are located, covering an area of more than 5 million hectares and is known for its diverse landscape and great variety of wildlife (

Figure 1). The area has a variety of ecosystems such as woodlands, grasslands, riverine forests and swamps, all becoming important habitats for wildlife, such as elephants (

Loxodonta africana), black rhinoceros (

Diceros bicornis), cheetahs (

Gattus pardus), giraffes (

Giraffa camelopardalis), hippopotamuses (

Hippopotamus amphibius) and crocodile (

Crocodylus siamensis). The wild animals cause damage to crops, livestock and houses of the neighboring communities, which often leads to human-animal conflicts. At the same time, there are many communities around the reserve, and in recent years, due to the growing population and the gradual increase in the use of natural resources, the fringe area adjacent to the reserve has become more fertile, which has attracted a lot of people interested in occupying the land for cultivation and animal husbandry. The conflict between conservation and development in this area is obvious, so to better protect biodiversity, it is of great significance to explore and study the willingness and action of community residents to participate in conservation as a way to resolve the harm caused by the conflict.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area.

2.2. Data Collection

In 2019, our research team travelled to the Mikumi-Selous region of Tanzania to conduct a pre-survey, with the main methodology being semi-structured interviews. The objectives of the pre-survey included: to understand the current situation of conflict between wildlife and neighboring communities in the reserve and collect relevant secondary data; to listen to the opinions of various stakeholders, and to amend and improve the questionnaire and the survey method in terms of problems and applicability; and to select suitable areas for the subsequent survey of community residents. Our survey targets were mainly local government departments, scientific research institutions and communities in conflict. We travelled to TAWA, Morogoro District Council and Mvomero District Council, three different types of nature reserves (former Selous Sanctuary, Mikumi National Park and Jukumu WMA) and four surrounding communities (Mkata, Bonye, Kisaki and Matambwe), and conducted semi-structured interviews with many experienced staff members to obtain relevant information. Through the pre-survey, we selected 4 villages in Mikumi-Selous area as the official research area and used the questionnaire method to obtain accurate data at the level of the community residents. Based on the pre-survey and semi-structured interviews, we listened to all the parties and adjusted the questionnaire by deleting and modifying the options that did not fit the local conditions to make the questionnaire more comprehensible.

Due to COVID-19, our formal research was postponed until November 2022. We travelled to 4 villages located around Mikumi National Park and Nyerere National Park in Tanzania to conduct a questionnaire survey with 200 local residents. The entire survey was conducted in commonly spoken languages in Tanzania (Kiswahili and English) by a total of 4 surveyors, with a local university student volunteering to assist us with translation to facilitate our survey smoothly. Each questionnaire took about 30 minutes to complete. The questionnaire was divided into 3 parts: the first part dealt with basic demographic and household information, including gender, age, education level, occupation and income from agriculture, forestry and animal husbandry; the second part investigated the conflict between the national park and the community residents, including the type of conflict, conflict losses, etc.; and the third part investigated the residents’ protection cognition, attitudes toward and protection actions taken to protect the national park. The basic information of the questionnaire respondents is shown in

Table 1.

We also conducted interviews with experienced employees of Mikumi National Park and Selous Sanctuary (now Nyerere National Park) and Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA) staff, and administrators of the administrative board and tourists were invited to discuss some key issues separately, totaling 14 people. Most of the interviews were recorded with the permission of the participants. By comparing answers from different viewpoints, we could make unbiased judgments on the various issues.

Table 1.

Basic profile of respondents (n = 200)

Table 1.

Basic profile of respondents (n = 200)

| diagnostic property |

form |

frequency |

Frequency (%) |

| gender |

male |

139 |

69.5 |

| female |

61 |

30.5 |

| age |

30 years and under |

56 |

28 |

| 30-50 years |

105 |

52.5 |

| 50 and over |

39 |

19.5 |

| education level |

below secondary |

109 |

54.5 |

| secondary school - university |

72 |

36 |

| university and above |

19 |

9.5 |

| occupation |

peasants |

163 |

81.5 |

| the rest |

37 |

18.5 |

| length of residence |

1-10 years |

37 |

18.5 |

| 11-20 years |

52 |

26 |

| 21-30 years |

45 |

22.5 |

| 31-40 years |

39 |

19.5 |

| More than 40 years |

27 |

13.5 |

| area of residence |

Mloka |

47 |

23.5 |

| Bonye |

35 |

17.5 |

| Matambwe |

61 |

30.5 |

| Kisaki |

57 |

28.5 |

2.3. Variable Selection

To a certain extent, residents’ attitudes and actions towards protection can reflect the willingness of the whole community to participate in and respond to conflict management. The stronger the residents’ willingness to protect or the more active their protective behaviors are, the more willing they are to participate in conflict management. Therefore, family characteristics, protection benefits, protection costs, protection cognition, protection willingness and protection actions are selected as the main research variables in this study. Since the above variables are all latent variables that are not easy to observe directly, we combine them with existing studies and select land area, distance from residence to the boundary of the conservation area, household income, and time spent living in the community to describe the household characteristics of residents; the variable of protection benefits selects income from tourism as well as possible job opportunities provided by the community development projects and the conservation area to describe the benefits that the residents get from the conservation policy; and the variable of conservation costs selects the benefits that residents get from the conservation policy because of the community development projects and the conservation area. The conservation cost variable captures the economic losses borne by residents as a result of conservation, including the restrictions on nature use imposed by conservation policies and the loss of houses, livestock, and crops due to wildlife destruction; the conservation cognition variable captures the improvement of livelihoods and the optimization of living conditions for residents as a result of conservation policies and development measures in the protected area; and the willingness to conserve variable mainly captures the willingness of residents to establish and improve the protected area, including the willingness to spend money and time; the conservation action variable is mainly characterized by the residents’ real participation in conservation actions and their continued participation in the future. The explanations of the variables are shown in

Table 2.

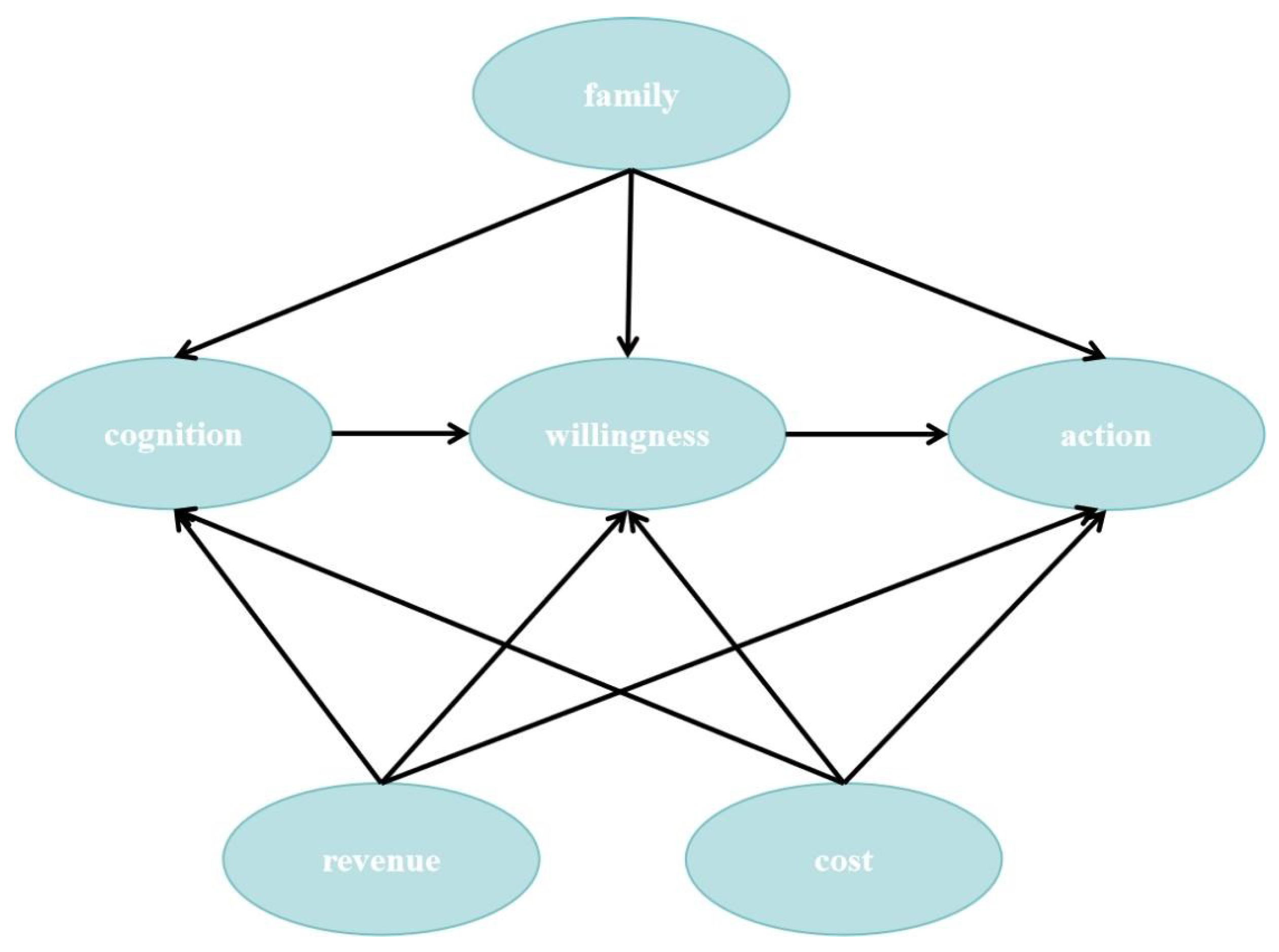

2.4. Model Setting

Based on the above analysis, there is a complex relationship between residents’ perception cognition, willingness and action. The traditional measurement method has some limitations, because although it allows the dependent variable to have measurement error, it needs to assume that the independent variable does not have error, so the traditional measurement cannot deal with the situation where the independent variable cannot be measured, and structural equations can deal with the latent variable and its indicators at the same time, so it is chosen to use Structural Equation Model (SEM) to analyze the link between them. Currently, structural equation model is divided into two mainstream research approaches: one is covariance-based structural equation model(CB-SEM) and partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM). CB-SEM estimates the relationship between variables by minimizing the difference between the theoretical and estimated covariance matrices, and PLS-SEM determines the relationship between the variables by maximizing the explanatory variance of endogenous latent variables. In this paper, the PLS-SEM model is selected for further analysis based on SmartPLS 4.0 software. The PLS-SEM model allows for the estimation of complex causal relationships using empirical data, and is an approach based on latent variable path modelling. Its advantage is that it can minimize the residuals of endogenous variables and construct the minimization of residuals [

38] and can effectively overcome the problem of covariance between observed variables. Thus, the model can well meet the needs of this study to conduct research and analysis in the state of small sample size.

PLS-SEM consists of two sets of theoretical models, one is the structural model, which is used to define the linear relationship between the latent independent variables and the latent dependent variables, and the other is the measurement model, which is used to define the relationship between the latent variables and the measurement variables. Since the reflective indicators selected in this paper can be directly reflected to the latent variables and have one-way correlation, the reflective model in the measurement model is selected for model construction. The equations of each model are shown below:

Measurement equations of internal variables (dependent variables):

Measurement equations of external variables (independent variables):

Where is the endogenous latent variable; represents the relationship between endogenous latent variables; is the exogenous latent variable; represents the linear relationship between endogenous and exogenous latent variables. In the measurement equations of internal and external variables: represents the factor load matrix of endogenous observed variable to endogenous latent variable ; represents the factor load matrix of exogenous observed variable to exogenous latent variable ; and are the parts that cannot be explained by the measurement model and are the measurement error terms.

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework based on structural equation modelling.

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework based on structural equation modelling.

3. Results

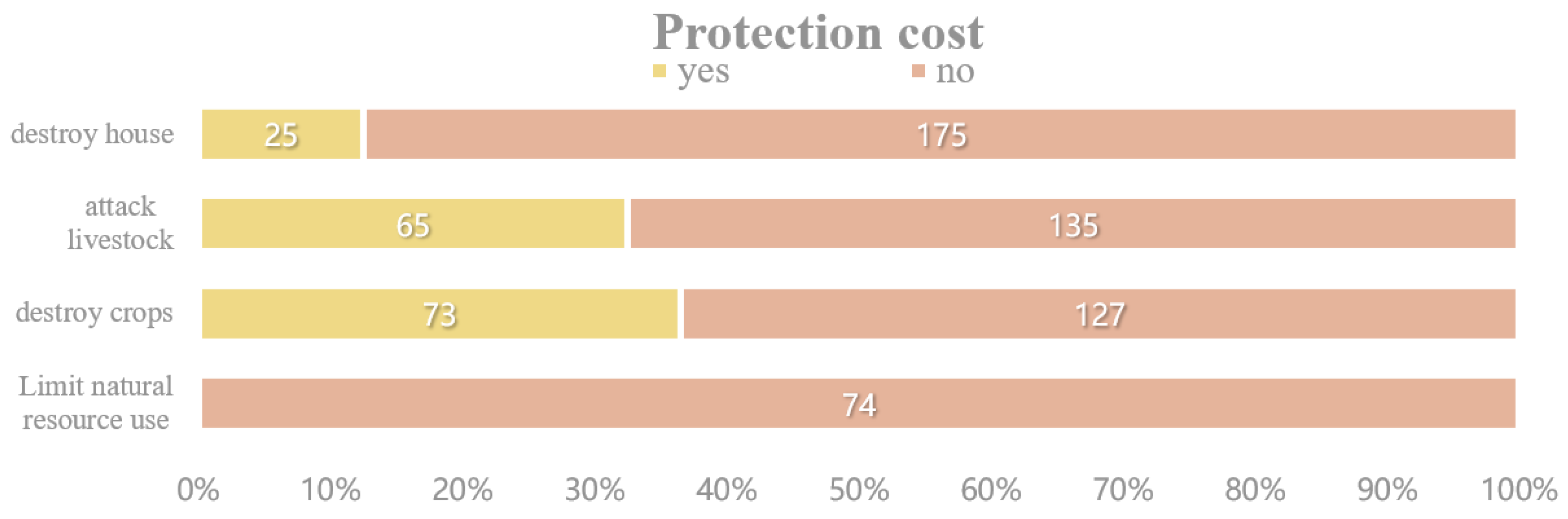

3.1. Status of Conflicts between Nature Reserves and Neighboring Communities

Conflicts between Tanzanian conservancies and community residents are mainly characterized by biodiversity conservation policies that severely restrict the use and exploitation of natural resources by community residents, and by wildlife-human conflicts. The latter is a two-pronged conflict that includes both the problems of habitat destruction, overhunting, and overexploitation of wildlife by residents, as well as the destruction of agricultural products by wildlife (stealing and eating of crops, trampling of farmland and pasture, stealing of honey, etc.), harm to livestock and poultry (predation on livestock, raiding of livestock), damage to household property (destruction of houses, breaking and entering and stealing of food, and destruction of means of production), and damage to personal safety (trampling, toppling, cannibalism). The survey found that 63% (n = 200) of the respondents indicated that they have limited the use of natural resources, and 36.5%, 32.5% and 12.5% of the respondents were affected by wildlife destroying crops, attacking livestock and destroying houses respectively (n = 200). It can be observed that many residents are paying a huge price for wildlife conservation and their livelihoods are severely affected.

Figure 3.

Status of conflicts between nature reserves and neighboring communities

Figure 3.

Status of conflicts between nature reserves and neighboring communities

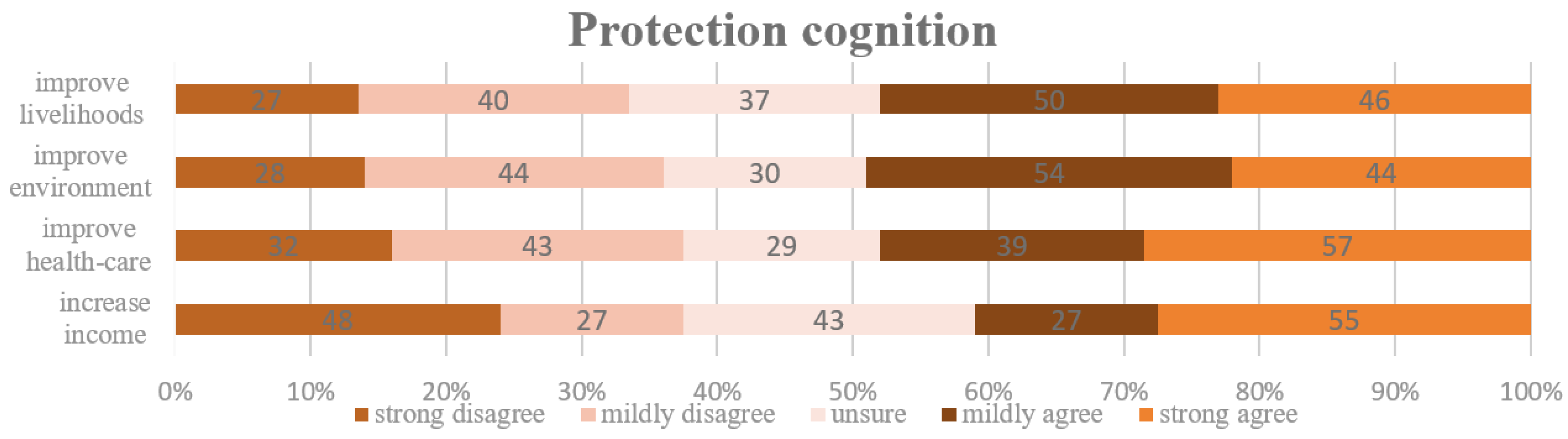

3.2. Community Residents’ Cognition, Willingness and Action Towards Biodiversity Conservation

The survey results show that nearly half of the residents have a positive attitude towards conservation cognition. 41% (n = 200) of respondents believe that community participation in conservancy conservation policies and development measures has led to an increase in residents’ income, 48% (n = 200) of respondents believe that the knowledge dissemination and technical training provided by the conservancy has improved residents’ personal qualities and livelihoods, 49% (n = 200) believe that conservancy conservation policies and development measures have improved the surrounding natural environment, and 48% (n = 200) believe that conservancy conservation policies and development measures have improved local healthcare, transport and other infrastructural conditions. (

Figure 4).

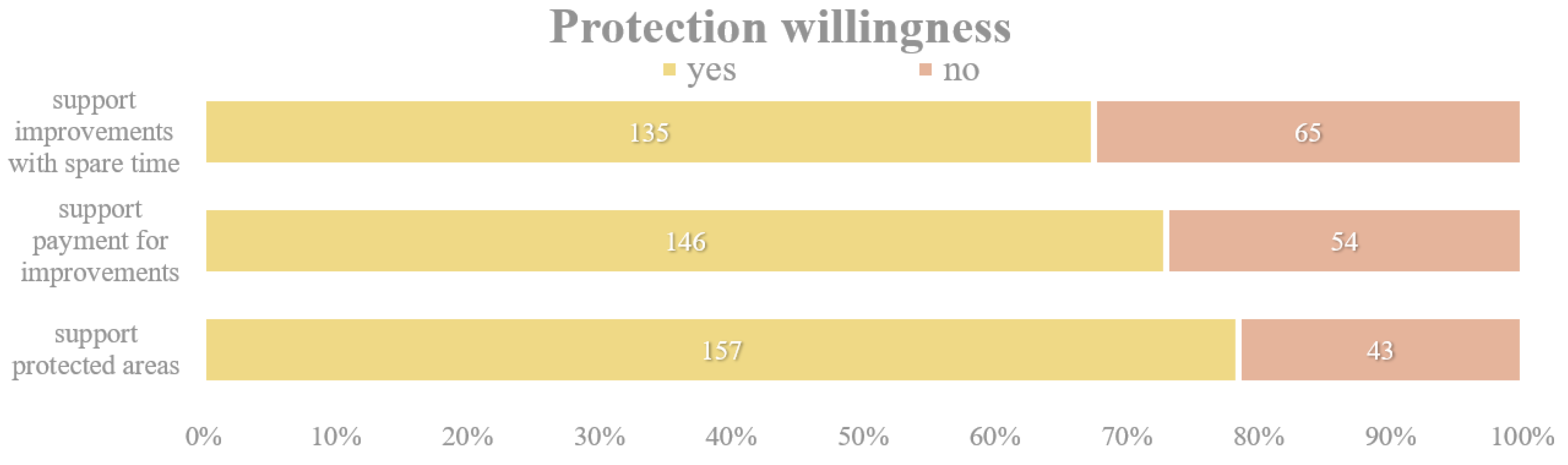

In the survey on the protection willingness and action of community residents in the Mikumi-Selous region, we can see that 80% of the respondents support the establishment of protected areas as well as their willingness to spend time and money to improve the protection of nature reserves (

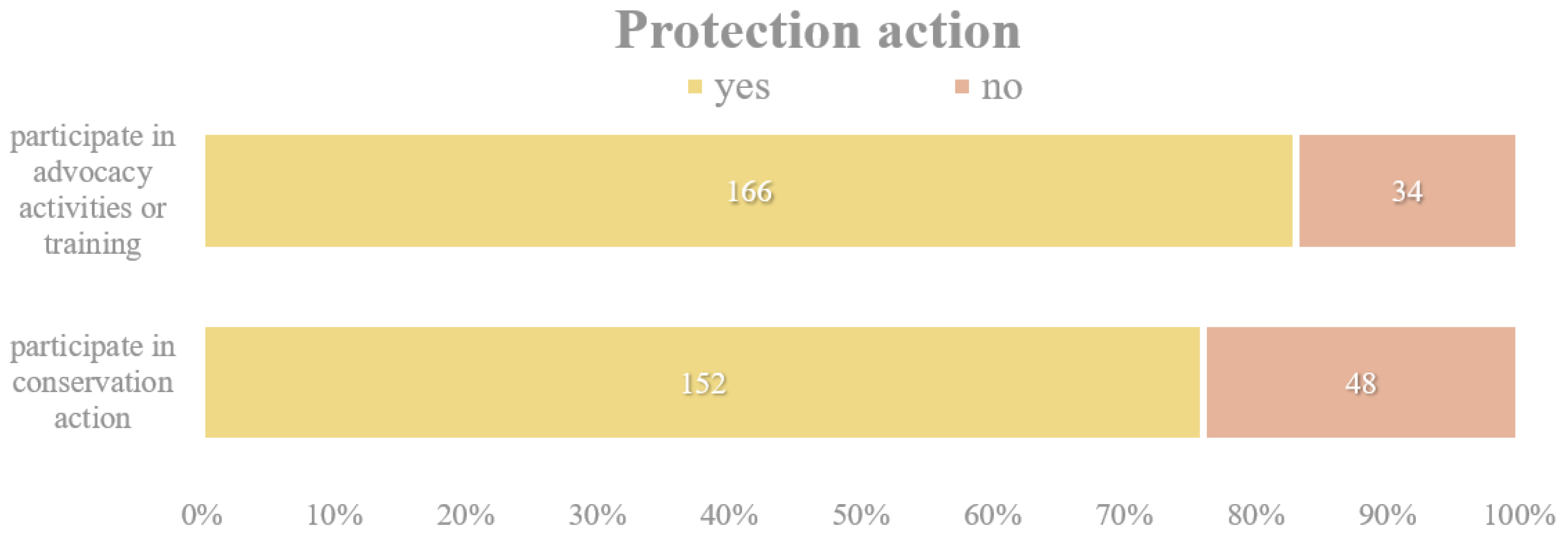

Figure 5), and nearly 90% of the residents have already been involved in conservation or awareness-raising activities in protected areas (

Figure 6). This result shows that the residents of the area have a high level of awareness and responsibility for wildlife conservation, they recognize the importance of protected areas for maintaining ecological balance and biodiversity, and are willing to actively participate in conservation actions.

3.3. Model Reliability and Validity Tests

The measurement model needs to be validated before the model test, which contains the reliability test and validity test. Cronbach’s α coefficient and composite reliability (CR) were used as the test of internal consistency. Usually, a Cronbach’s α of <0.35 indicates low reliability; 0.35 ≤ Cronbach’s α < 0.70 indicates moderate reliability; Cronbach’s α > 0.70 indicates high reliability. The higher the CR value, the higher the reliability. As a rule of thumb, a CR value between 0.60 and 0.70 is considered "acceptable in exploratory studies", and a CR value between 0.7 and 0.9 indicates "satisfactory to good" reliability. As can be seen in

Table 3, the CR values and Cronbach’s α for all latent variables satisfy the criteria, providing evidence of good internal consistency in the measurement model. In addition, in general, the standardized factor loading of the observed variables is greater than 0.5 indicating that each observed variable has good explanatory power for the corresponding latent variable. All the standardized factor loadings in this study are greater than the test criteria, which again indicates that the measurement model has high reliability. In addition, a VIF value of less than 5 indicates that there is no problem of multicollinearity.

Next, the validity of the measurement model needs to be assessed by testing convergent validity and discriminant validity. The metric used to assess convergent validity is the average variance of all items extracted on each construct, i.e., the average variance extracted (AVE).An acceptable value for the AVE is 0.50 or higher, which indicates that the construct explains at least 50% of the variance in its items. According to

Table 3, it can be seen that the data in this part of the study meet the requirements. And discriminant validity, which represents the degree of effective differentiation between latent variables. It can be tested by the criterion that the square root of the AVE value is greater than the correlation coefficient of the other latent variables. From

Table 4, it can be seen that the square root of AVE of the latent variables in this part is greater than the correlation coefficient between the latent variables, which indicates that the measurement model has good discriminant validity.

In addition, recent research suggests that this criterion may not be sufficiently robust in discriminant validity assessments, especially when structured with only slightly different indicator loadings (e.g., all factor loadings between 0.65 and 0.85) [

39].As an alternative, Henseler proposed heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) as a new metric for discriminant validity assessment [

39]. When the HTMT value is high, it indicates low discriminant validity, and Henseler et al. [

39] proposed a threshold of 0.9 for the structural model. As can be seen in

Table 5, the HTMT values for all latent variables in this part of the study were less than 0.9, indicating high discriminant validity of the measurement model in this part of the study.

Table 3.

Results of model reliability test

Table 3.

Results of model reliability test

| Constructs |

Items |

Factor loadings |

VIF |

Cronbach’s alpha |

CR |

AVE |

| action |

action1 |

0.955 |

2.233 |

0.853 |

0.929 |

0.868 |

| action2 |

0.908 |

2.233 |

| cognition |

cognition1 |

0.800 |

1.351 |

0.715 |

0.82 |

0.535 |

| Cognition2 |

0.682 |

1.421 |

| Cognition3 |

0.783 |

1.524 |

| Cognition4 |

0.648 |

1.257 |

| cost |

cost1 |

0.785 |

1.44 |

0.762 |

0.85 |

0.589 |

| cost2 |

0.848 |

2.258 |

| cost3 |

0.803 |

2.15 |

| Cost4 |

0.613 |

1.164 |

| family |

family1 |

0.888 |

2.252 |

0.736 |

0.831 |

0.561 |

| family2 |

0.809 |

1.46 |

| family3 |

0.519 |

1.266 |

| family4 |

0.728 |

1.618 |

| revenue |

revenue1 |

0.628 |

1.626 |

0.766 |

0.814 |

0.697 |

| revenue2 |

1.000 |

1.626 |

| willingness |

Willingness1 |

0.920 |

2.206 |

0.705 |

0.837 |

0.636 |

| Willingness2 |

0.631 |

1.328 |

| Willingness3 |

0.816 |

1.778 |

Table 4.

Square root of AVE and correlation coefficient between latent variables.

Table 4.

Square root of AVE and correlation coefficient between latent variables.

| |

action |

cognition |

cost |

family |

revenue |

willingness |

| action |

0.932 |

|

|

|

|

|

| cognition |

0.536 |

0.731 |

|

|

|

|

| cost |

-0.105 |

-0.338 |

0.768 |

|

|

|

| family |

-0.002 |

-0.234 |

0.386 |

0.749 |

|

|

| revenue |

0.202 |

0.264 |

-0.02 |

0.068 |

0.835 |

|

| willingness |

0.545 |

0.548 |

-0.49 |

-0.212 |

0.045 |

0.798 |

Table 5.

Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) results.

Table 5.

Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) results.

| |

action |

cognition |

cost |

family |

revenue |

willingness |

| action |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

| cognition |

0.603 |

- |

|

|

|

|

| cost |

0.142 |

0.453 |

- |

|

|

|

| family |

0.053 |

0.315 |

0.51 |

- |

|

|

| revenue |

0.181 |

0.249 |

0.141 |

0.12 |

- |

|

| willingness |

0.681 |

0.739 |

0.652 |

0.27 |

0.119 |

- |

3.4. Overall Model Testing

Based on the good results of the model reliability and validity tests, the study used SmartPLS 4.0 software to calculate the T-statistic of each path coefficient after 5000 sample repetitions using the Bootstrapping method, and the T-value is a significance level indicator used to indicate the sample size and the significance of the statistical model.

3.4.1. Analysis of Direct Effects

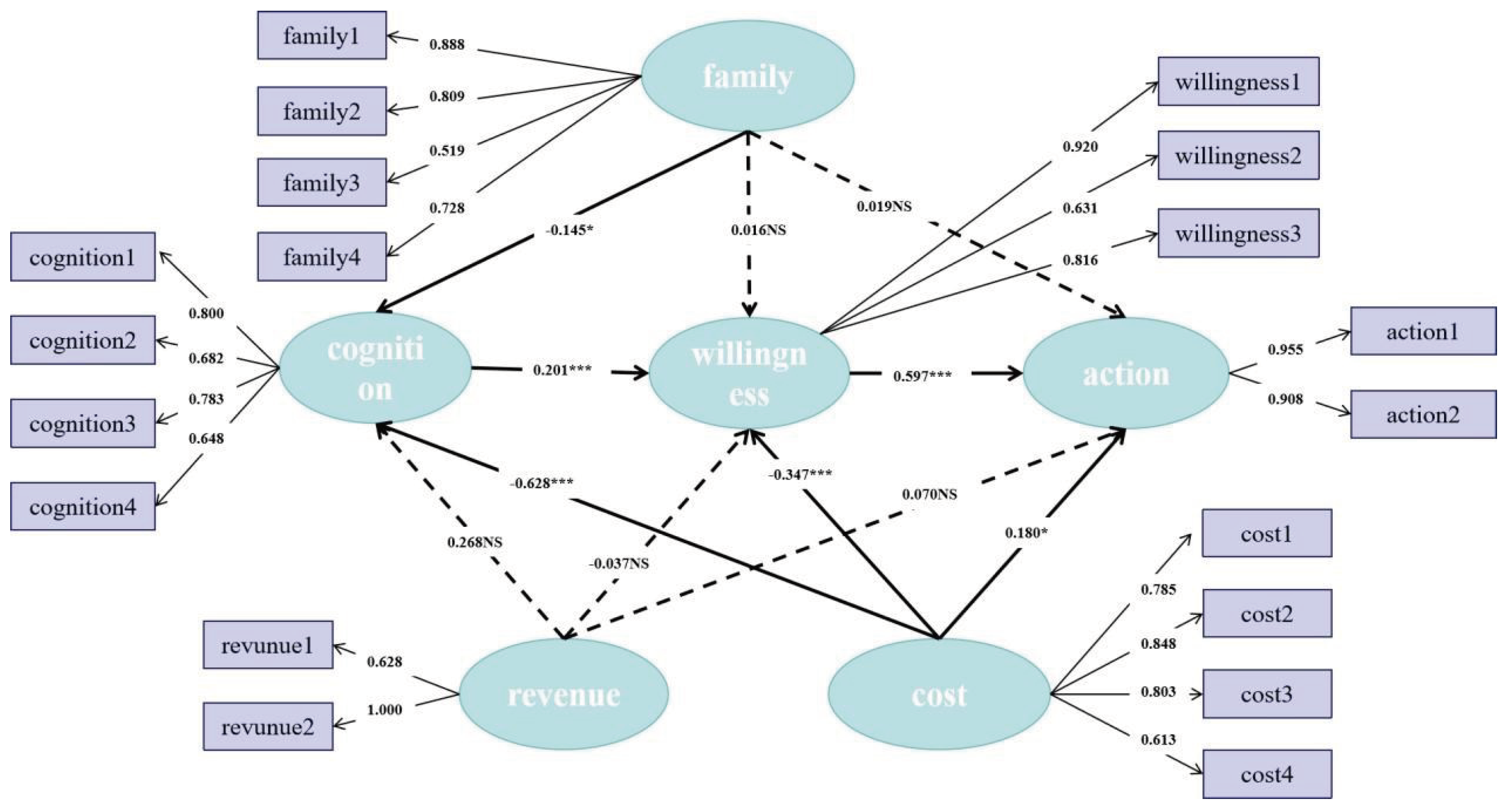

Figure 7 illustrates the path coefficients and significance results between the latent variables to characterize the direct effect relationship between the latent variables.

Household characteristics have a significant negative effect on conservation cognition, and no significant effect on conservation willingness and action; the possible reason for this is that the larger land area, higher income from agriculture and forestry, closer to the protected area, or longer years of residence in the household characteristics imply that there is a greater demand for land exploitation and use by the community’s residents, which may contribute to the increase of pressure on natural resource use, aggravate conflicts with wildlife, and thus pose a threat to conservation threats, and then conservation cognition may decrease. Although theoretically family characteristics may influence the conservation intentions and behavior of community residents, in practice, residents’ decisions are often influenced by considerations of economic interests. The cost of conservation has a significant positive effect on conservation action, and the cost of conservation has a significant negative effect on conservation cognition and willingness to conserve; the possible reason for this is that the most serious conflict between the community and the protected area is the conflict between people and wildlife, but it is also affected by the conservation policy that can not produce actions to harm the wildlife, so the residents will voluntarily participate in the use of physical isolation (e.g., setting up fences, hedges, etc.) to lower the wildlife’s harm to people, which in itself is a kind of conservation behavior. However, if the cost of conservation is too high, the residents will have a strong aversion to conservation, which is manifested in the negative attitude of conservation cognition and willingness. Protection revenue do not have a significant effect on conservation cognition, willingness and action. The possible reason for this is that residents of communities around nature reserves may face trade-offs between economic benefits and ecological conservation. Although eco-tourism and other methods can bring economic benefits to families, they may have a limited role and not be able to satisfy the basic needs of life, in which case, residents attach less importance to conservation willingness and action, and prefer one-sided economic rationality to achieve a rapid increase in income. This may also cause some pressure and damage to the ecological environment if over-exploitation behavior occurs due to excessive demand for economic benefits. In addition, the variability of residents’ cognition of conservation benefits may also contribute to this result, e.g., some residents believe that the protected area can bring them economic and non-economic benefits, while others do not benefit from it or have less benefits, which may also lead to the positive non-significance of conservation benefits on conservation cognition and willingness. Conservation cognition has a significant positive effect on willingness, and conservation willingness has a significant positive effect on conservation action; this suggests that residents have a high perception of ecological and biodiversity conservation, which leads to a high willingness to participate in conservation, which ultimately manifests itself in participation in the practice of conservation behavior.

3.4.2. Analysis of Indirect and Total Effects

Table 6 reports the indirect and total effects of all path endpoints for protection willingness and behavior. The analysis of indirect effects shows that, on the one hand, cognition and willingness are good bridges from protection cost to protection behavior, and the three paths of "cognition -> willingness -> action, cost -> cognition -> willingness -> action, cost -> willingness -> action" all passed the test (p < 0.001 or p < 0.01), the path coefficients of the path of protection cognition-protection willingness are positive, and the other two paths are negative. This suggests that willingness not only has a direct effect on behavior, but also mediates the effects of protection cognition and protection costs on protection action. The other paths are not significant because family characteristics and benefits of protection themselves have a low association with protection behavior, making it difficult for cognition and willingness to play a mediating role. By comparing the total effects of different latent variables on the paths to conservation behavior, it can be found that conservation cognition have a significant positive effect on conservation willingness and behavior, conservation costs have a significant negative effect on cognition and willingness, family characteristics have a significant positive effect on cognition, and willingness has a significant positive effect on conservation behavior. The construction and development of the protected area is closely related to the life of the surrounding residents, and the surrounding community is constantly involved in the construction and management of the protected area, so the residents’ cognition of the protection of the protected area affects their willingness to protect and protection behavior. From the perspective of economics, residents as rational economic man, in the process of protection, if the cost is too high, it will inevitably have a negative impact on their protection behavior, so the protection work should also take into account the inhibition effect of the protection cost on the residents’ willingness to protect and behavior. The natural resource endowment, economic base, geographic location, and length of residence at the place of living of resident households are all important reflections of household capital and productive capacity, which in turn affects household perceptions of conservation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Status of Conflicts between Nature Reserves and Neighboring Communities

For the time being, the conflicts between nature reserves and communities can be summarized in four areas: first, the restricted use of natural resources. Nature reserves have some degree of constraints on the use of resources by residents, such as restrictions on timber harvesting, grazing, and wild plant collection [

40]. Second, development opportunities are lost. Strict protection makes the local attraction of capital investment activities greatly affected, and in order to enhance ecological functions and improve the ecological environment, it will reduce the resource development and pollution emission of high-environmental-risk industries [

41]. The reduction and exit of the industries reduce the employment opportunities and income sources of the community. Third, land use is restricted. The expropriation of agricultural land includes homesteads, arable land and forest land. The acquisition of community land by conservancies globally usually has a stronger overtone of government coercion, with a lack of communication with the community, exacerbating residents’ grievances [

42]. Fourth, human-wildlife conflicts are frequent. Increasing human-wildlife conflicts have become a common problem faced by protected areas worldwide. Despite the prevalence and severity of wildlife killings, compensation mechanisms for wildlife incidents remain inadequate [

43]. These problems exist in Tanzania.

4.2. Manifestations of Community Participation in Conflict Governance

Scholars have also carried out a great deal of exploration of mechanisms for coordinating conservation and community development. The first is to carry out community development projects. At present, some national parks have set up community co-management sections, with specialized personnel to interface with community residents and jointly carry out community development projects. Conservation development projects usually include clean energy projects (e.g., solar energy, biogas digesters, wood-saving stoves), livelihood development projects (speciality farming), and personnel training [

28]. However, many livelihood projects are less sustainable due to deficiencies in market information and other aspects, and often residents also gradually withdraw from participating livelihood projects after the end of the project period [

34]. Compared with energy and livelihood projects, education and training of communities by conservation agencies is considered to be the most successful of development projects [

27]. This has been demonstrated in Tanzania, where sensitization and education by conservancy management agencies influenced residents’ cognition of conservation and made them more willing to participate in conservation actions. The second is to increase non-farm employment opportunities such as eco-tourism. Eco-tourism in protected areas generates direct income and is therefore considered an ideal model for simultaneous conservation and development of habitats [

29]. Farmers’ revenues from eco-tourism include selling products and services (running a farmhouse or shop) or through revenue-sharing mechanisms (e.g., a share of ticket revenues). Many eco-tourism projects also generate non-economic gains such as increased capacity of community residents, easier access to information, financial development, and market development [

36,

44,

45]. These non-economic gains can help residents diversify their incomes, de-farm, and improve household livelihoods.

4.3. Factors Affecting Community Participation in Protection Action

People living in communities surrounding nature reserves possess different livelihood capitals due to a variety of factors such as their living background, economic status, and cultural traditions. Changes in livelihood capital can directly lead to changes in livelihood strategies [

46], and profoundly affects their conservation cognition, willingness and behavior. Generally, the natural capital and economic capital of household characteristics combine to influence their willingness and behavior. If a household is richer in natural and economic capital, residents may have more time and capital to invest in conservation.

Community participation is an important link in easing the contradiction between conservation and development, and plays an important role in promoting the coordination of conservation and development. Generally, community co-management is the main form of community residents’ participation in conservation actions, which is conducive to the promotion of community economic development and sustainable resource use. Heslinga et al. [

47] believed that the more the residents of the communities around the nature reserves gain from tourism, the stronger their willingness to protect; Duan et al. [

48] analyzed the conservation gains and losses of residents around nature reserves in three provinces in China, and found that the benefits of ecological conservation to the residents are mainly improved living conditions and increased tourism income, and that conservation gains are basically positively correlated with residents’ protection willingness. Spiteri and Nepal [

49] studied the economic benefits of farmers in communities where eco-tourism is the main focus, and found that their economic benefits are much higher than those in non-tourism areas, and that farmers who receive higher economic benefits are more inclined to participate in conservation activities.

In the process of biodiversity conservation, the conservation costs borne by the community are reflected in many aspects, such as property losses caused by wild animals in the reserve to residents, destruction of houses and crops, attacks on livestock, etc., so the conservation costs are an important factor influencing the conservation willingness and behavior of communities around the reserve. Wang’s [

50] survey of communities around the Qinling Nature Reserve in China found that crops in the community were often damaged by wild boars, hares and black bears, causing serious economic losses to farmers; By studying farmers’ perceptions of cost-benefit in the neighborhood of seven national parks in the Indian and Nepalese regions, Karanth and Nepal [

37] found that farmers’ perceptions of benefits were insensitive, while perceptions of costs were very sensitive. Other scholars have shown that people who are victims of wildlife depredation or have limited access to forest resources may exhibit negative perceptions and attitudes towards nearby protected areas [

51]. This is consistent with the findings of this study. Most of the residents perceived that conservation behavior increased the economic cost of living but not the economic benefits. Therefore, the more costs community residents bear in conservation behaviors, the more likely they are to reduce their conservation intentions and behaviors.

The ABC attitude model theory suggests that an individual’s intrinsic cognition can change behavioral willingness, and the higher the level of residents’ cognition, the stronger their willingness to protect. There was a relatively significant positive correlation between environmental cognition and behavioral willingness [

52,

53]; the conservation willingness of the residents in the community was the intrinsic driving force of people’s actions towards conservation, while the actual conservation behavior was the specific embodiment of the conservation willingness. He et al. [

54] showed that residents’ willingness to protect nature reserves affects their attitudes towards the establishment of nature reserves, and that positive attitudes can promote community and reserve management, thereby reducing conflicts. This suggests that willingness to conserve is an important factor driving conservation behavior.

5. Conclusion

We found that the conflict between the conservancy and the community manifests itself in many ways, with the core and most acute manifestations of the conflict being the destruction of community crops by wildlife, the harm to livestock, the damage to household property such as houses, and most critically, the attacks on people, and in turn, the hunting and killing of wildlife by people forming the interactive process of the conflict. In addition, prohibitions on land development and restrictions on the use of natural resources are also important manifestations of the conflict between the reserve and the community. The antagonistic and conflicting relationship between nature reserves and neighboring residents not only affects the production and life of villagers, but also hinders community development. Residents in the community undoubtedly play an important role in the conflict management between nature reserves and the community. Residents are the core stakeholders of conflict governance. They live in the conflict environment and are directly affected by the conflict. Their cognition of the protected area, their willingness to govern and their responsive attitude all have an important impact on the effectiveness of conflict governance. Through empirical analysis, it is found that residents’ cognition of protection has a significant positive effect on willingness to protect and protection behavior, and it is also verified that willingness to protect also positively affects residents’ protection action, indicating that the higher the residents’ perception of protection and the stronger their willingness to protect, then their participation in protection actions will be more positive. Compared with the family characteristics of community residents and the benefits of protection, the cost of protection is more likely to affect the residents’ willingness and their behaviors. Therefore, it is recommended to effectively resolve conflicts by raising the awareness of residents, stimulating the willingness to protect and encouraging positive conservation behavior, so as to achieve harmonious coexistence between nature reserves and the surrounding communities. The conflict between conservation and development is a global problem, and its formation and development is a complex and gradual evolutionary process, and the mitigation and management of the conflict cannot be achieved overnight. Although the governance and research on conflict has been almost anthropocentric, the participation of multiple interest groups is an important direction of modern conflict governance. It is suggested that future research pay more attention to the co-governance and co-funding of multi-interest groups in conflict governance by governments, enterprises, communities, international organizations and universities, so as to enhance the community’s motivation to participate in protection and jointly promote conflict resolution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M., Y.H. and Y.W.; Methodology, L.M., J.W. and H.Z.; Software, L.M.; Validation, L.M., J.W. and H.Z.; Investigation, H.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation, L.M., J.W. and H.Z.; Writing—review and editing, L.M., Y.H., and Y.W.; Visualization, L.M.; Supervision, Y.H. and Y.W.; Project administration, Y.H. and Y.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.H. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.71861147001) and the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No.21ZDA090).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, in our study, participants were invited to join in the survey voluntarily and anonymously without offending their privacy and generating ethic issues. Therefore, we did not seek approval for this case. All human studies where non-routine procedures are not used in this study. Before all interviews, the content of the study was explained to the interviewees and their agreement was obtained.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of privacy concerns.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff of nature reserves and national parks for their help and support, and all the researchers for their hard work in collecting the questionnaires.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Coates, D. Strategic Plan for Biodiversity (2011–2020) and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. In The Wetland Book; Finlayson, C.M., Everard, M., Irvine, K., McInnes, R.J., Middleton, B.A., Van Dam, A.A., Davidson, N.C., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2016; pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-94-007-6172-8. [Google Scholar]

- Manolache, S.; Nita, A.; Ciocanea, C.M.; Popescu, V.D.; Rozylowicz, L. Power, Influence and Structure in Natura 2000 Governance Networks. A Comparative Analysis of Two Protected Areas in Romania. Journal of Environmental Management 2018, 212, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP-WCMC and IUCN. Protected Planet Report 2020; UNEP-WCMC and IUCN: Cambridge UK and Gland: Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Guo, D.F.; Lu, W.T.; Xu, H. How Does Ecological Protection Redline Policy Affect Regional Land Use and Ecosystem Services? Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2023, 100, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.M.; O’Leary, B.C.; McCauley, D.J.; Cury, P.M.; Duarte, C.M.; Lubchenco, J.; Pauly, D.; Sáenz-Arroyo, A.; Sumaila, U.R.; Wilson, R.W.; et al. Marine Reserves Can Mitigate and Promote Adaptation to Climate Change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6167–6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redpath, S.M.; Bhatia, S.; Young, J. Tilting at Wildlife: Reconsidering Human–Wildlife Conflict. Oryx 2015, 49, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H. What do China’s nature reserves give to neighboring communities? --Based on data from a survey of farm households in Shaanxi, Sichuan, and Gansu provinces from 1998 to 2014. Management World 2017, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.B. Affirming New Directions in Planning Theory: Comanagement of Protected Areas. Society & Natural Resources 2001, 14, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Smith, D. Social Capital in Biodiversity Conservation and Management. Conservation Biology 2004, 18, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.; Cunningham, A.; Byarugaba, D.; Kayanja, F. Conservation in a Region of Political Instability: Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, Uganda. Conserv Biol 2000, 14, 1722–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. Opportunities and Barriers in the Implementation of Protected Area Management: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis of Case Studies from European Protected Areas: Opportunities and Barriers in Protected Area Management. The Geographical Journal 2011, 177, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbise, F. Attacks on Humans and Retaliatory Killing of Wild Carnivores in the Eastern Serengeti Ecosystem, Tanzania. Journal of Ecology and The Natural Environment 2021, 13, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.R.; Meng, R.; Pan, Z.; Zheng, Y.M.; Zeng, W.H. Research on the space-overlap and development conflicts between types of protected areas. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2019, 39, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Sanare, J.E.; Valli, D.; Leweri, C.; Glatzer, G.; Fishlock, V.; Treydte, A.C. A Socio-Ecological Approach to Understanding How Land Use Challenges Human-Elephant Coexistence in Northern Tanzania. Diversity 2022, 14, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Cai, Y.L.; Duan, J.H. On the Relationship among Interest Conflict, Institutional Arrangement and Management Effectiveness: An QCA Analysis on the Community Management of Foreign National Parks. Tourism Science 2019, 33, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongeneel, R.; Polman, N.; Slangen, L. Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Dutch Nature Policy: Transaction Costs and Land Market Impacts. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacho, O.J.; Milne, S.; Gonzalez, R.; Tacconi, L. Benefits and Costs of Deforestation by Smallholders: Implications for Forest Conservation and Climate Policy. Ecological Economics 2014, 107, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foya, Y.R.; Mgeni, C.P.; Kadigi, R.M.J.; Kimaro, M.H.; Hassan, S.N. Do Communities Understand the Impacts of Unlawful Bushmeat Hunting and Trade? Insights from Villagers Bordering Western Nyerere National Park Tanzania. Global Ecology and Conservation 2023, 46, e02626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Chen, J.F.; Cirella, G.T.; Xie, Y. Understanding and Mitigating the Purchase Intention of Medicines Containing Saiga Antelope Horn among Chinese Residents: An Analysis of Influencing Factors. Diversity 2024, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.C.; Marks, S.A. Transforming Rural Hunters into Conservationists: An Assessment of Community-Based Wildlife Management Programs in Africa. World Development 1995, 23, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaesel, H.; Hulme, D.; Murphree, M. African Wildlife and Livelihoods: The Promise and Performance of Community Conservation. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines 2002, 36, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songorwa, A.N. Community-Based Wildlife Management (CWM) in Tanzania: Are the Communities Interested? World Development 1999, 27, 2061–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.L.; Cazalis, V.; Dudley, N.; Hoffmann, M.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Stolton, S.; Visconti, P.; Woodley, S.; Kingston, N.; Lewis, E.; et al. Area-Based Conservation in the Twenty-First Century. Nature 2020, 586, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandiwa, E.; Heitkönig, I.M.A.; Lokhorst, A.M.; Prins, H.H.T.; Leeuwis, C. CAMPFIRE and Human-Wildlife Conflicts in Local Communities Bordering Northern Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe. E&S 2013, 18, art7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archabald, K.; Naughton-Treves, L. Tourism Revenue-Sharing around National Parks in Western Uganda: Early Efforts to Identify and Reward Local Communities. Envir. Conserv. 2001, 28, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robalino, J.; Villalobos, L. Protected Areas and Economic Welfare: An Impact Evaluation of National Parks on Local Workers’ Wages in Costa Rica. Envir. Dev. Econ. 2015, 20, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.J.; Corral, L.; Blackman, A.; Asner, G.; Lima, E. Effects of Protected Areas on Forest Cover Change and Local Communities: Evidence from the Peruvian Amazon. World Development 2016, 78, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.Y.; Han, X.; Hou, Y.L.; Wen, Y.L. Subjective Well-Being of Households in Rural Poverty Regions in Xiangxi, Hunan Province. Resources Science 2014, 36, 2174–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Cai, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wen, Y.L. Conservation, Ecotourism, Poverty, and Income Inequality – A Case Study of Nature Reserves in Qinling, China. World Development 2019, 115, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.P.; Nielsen, E. Indigenous People and Co-Management: Implications for Conflict Management. Environmental Science & Policy 2001, 4, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.Y.; Chen, L.X.; Lv, Y.H.; Fu, B.J. Harmonization of protected areas management and local development: methods, practices and lessons. Chinese Journal of Ecology 2005, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, N.M.; Coolsaet, B.; Sterling, E.J.; Loveridge, R.; Gross-Camp, N.D.; Wongbusarakum, S.; Sangha, K.K.; Scherl, L.M.; Phan, H.P.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; et al. The Role of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Effective and Equitable Conservation. E&S 2021, 26, art19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulimboka, R.; Mbise, F.P.; Nyahongo, J.; Røskaft, E. Awareness of Urban Communities on Biodiversity Conservation in Tanzania’s Protected Areas. Global Ecology and Conservation 2022, 38, e02251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H. Farmers’ Attitudes toward Ecological Conservation: New Findings and Policy Implications. Management World 2014, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.F.; Li, G.P.; Han, X.F. Conflict Between Farmers’ Ecological Protection and Development Intention in Nature Reserve: Based on the Research Data of 660 Households of Farmers Around the National Nature Reserve in Shaanxi. China Population, Resources and Environment 2015, 25, 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal, S.; Spiteri, A. Linking Livelihoods and Conservation: An Examination of Local Residents’ Perceived Linkages Between Conservation and Livelihood Benefits Around Nepal’s Chitwan National Park. Environmental Management 2011, 47, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karanth, K.K.; Nepal, S.K. Local Residents Perception of Benefits and Losses From Protected Areas in India and Nepal. Environmental Management 2012, 49, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manejar, A.J.A.; Sandoy, L.M.H.; Subade, R.F. Linking Marine Biodiversity Conservation and Poverty Alleviation: A Case Study in Selected Rural Communities of Sagay Marine Reserve, Negros Occidental. Marine Policy 2019, 104, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Bai, M.X. Ecological Compensation Fund Source Mechanism in Mining Area of China and Countermeasures. China Population, Resources and Environment 2015, 25, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, W.; Wen, Y.L. Impacts of Protected Areas on Local Livelihoods: Evidence of Giant Panda Biosphere Reserves in Sichuan Province, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.L.; Wen, Y.L. Analysis of Influence and Compensation Issue of Wild Animals Causing Accident to the Community Farmers——with an example of the Qinling natural preservation zone. Problems of Forestry Economics 2012, 32, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, P.J.; Hanauer, M.M. Protecting Ecosystems and Alleviating Poverty with Parks and Reserves: ‘Win-Win’ or Tradeoffs? Environ Resource Econ 2011, 48, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Walelign, S.Z.; Nielsen, M.R.; Smith-Hall, C. Protected Areas, Household Environmental Incomes and Well-Being in the Greater Serengeti-Mara Ecosystem. Forest Policy and Economics 2019, 106, 101948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa Karki, S. Do Protected Areas and Conservation Incentives Contribute to Sustainable Livelihoods? A Case Study of Bardia National Park, Nepal. Journal of Environmental Management 2013, 128, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heslinga, J.; Groote, P.; Vanclay, F. Strengthening Governance Processes to Improve Benefit-Sharing from Tourism in Protected Areas by Using Stakeholder Analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2019, 27, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, B.; Wen, Y.L. Perceptions of rural household surrounding the protection area on protection benefits and losses. Resources Science 2015, 37, 2471–2479. [Google Scholar]

- Spiteri, A.; Nepal, S.K. Evaluating Local Benefits from Conservation in Nepal’s Annapurna Conservation Area. Environmental Management 2008, 42, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H. The Construction and Management of China’s Nature Reserves in the Past Forty Years of Reform and Opening-up:Achievements, Challenges and Prospects. Chinese Rural Economy 2018, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf, T.; Radel, V.; Keuler, N. People’s Perceptions of Protected Areas across Spatial Scales. PARKS 2019, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Y.; Hou, P. Investigation and Research on Willingness of Citizen’s Environmental Behavior in Beijing. Chinese Journal of Population, Resources and Environment 2010, 20, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Jin, J. Analysis of Environmentally Friendly Behavior of Urban and Rural Residents in China and Its Comprehensive Influence Mechanisms--Based on Data from the 2013 China General Social Survey. Social Construction 2015, 2, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.Y.; Wei, Y.; Su, Y.; Min, Q.W. A grounded theory approach to understanding the mechanism of community participation in national park establishment and management. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2021, 41, 3021–3032. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).