Detailed Case Description

The patient is a 66 year old woman, with a medical history of cardiovascular disease (high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, previous myocardial infarction, mitral and tricuspid valve regurgitation), and combined hyperlipidemia. She presents to the emergency department with acute pain in the right hypochondriac and in the epigastric region that radiates in the back. The patient has a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 and is a heavy smoker (more than 20 cigarettes per day).

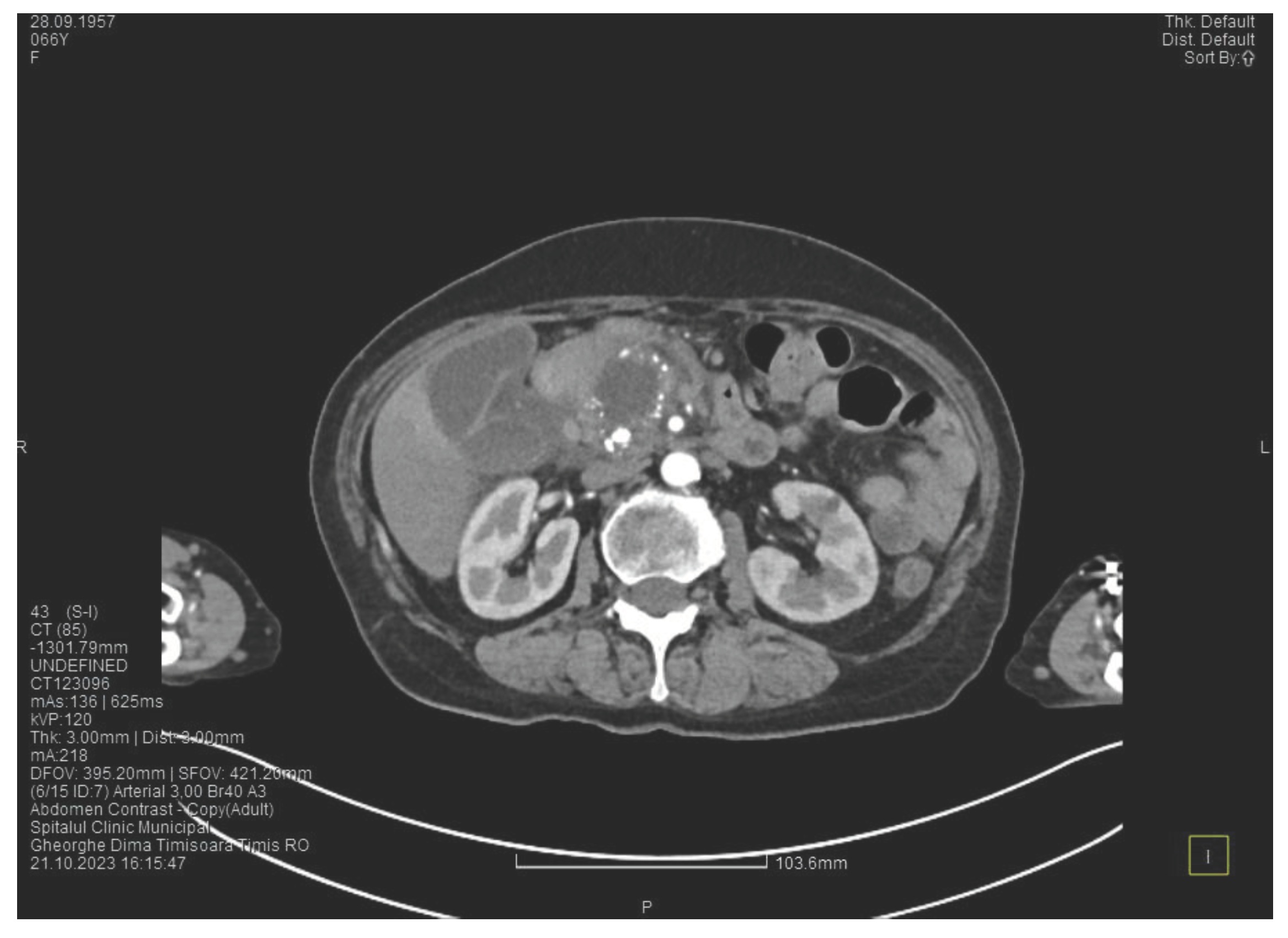

Laboratory tests show a serum lipase of more than 10 times above the upper normal range. The contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) shows multiple calcifications in the pancreatic tissue, dilatation of the main pancreatic duct of approximately 12.5 mm (

Figure 1), a non-iodophilic intraparenchymal cyst in the head of the pancreas with a size of 23/25 mm that associates acute inflammation (

Figure 2) and a densification of the peripancreatic fat, more intense at the head of the pancreas, as well as enlarged pericephalic and periaortocaval lymph nodes. There were no changes in the liver and the gallbladder, only a mild ectasia of the intrahepatic bile ducts, with no dilatation of the common bile duct. Other changes include multiple atheromas of the abdominal aorta. The symptoms, the lab results and the finding at CT scan led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

We initiated treatment with antispasmodic and antisecretory drugs as well as fluid replacement, followed by an improvement of the symptoms and of the lab results. The patient was discharged after 5 days.

Approximately one month later, the patient presented again to the emergency department, complaining of epigastric pain, fatigue and malaise. The lab results were unremarkable except a slighly increased serum lipase (about 1.5 times higher than the upper normal range).

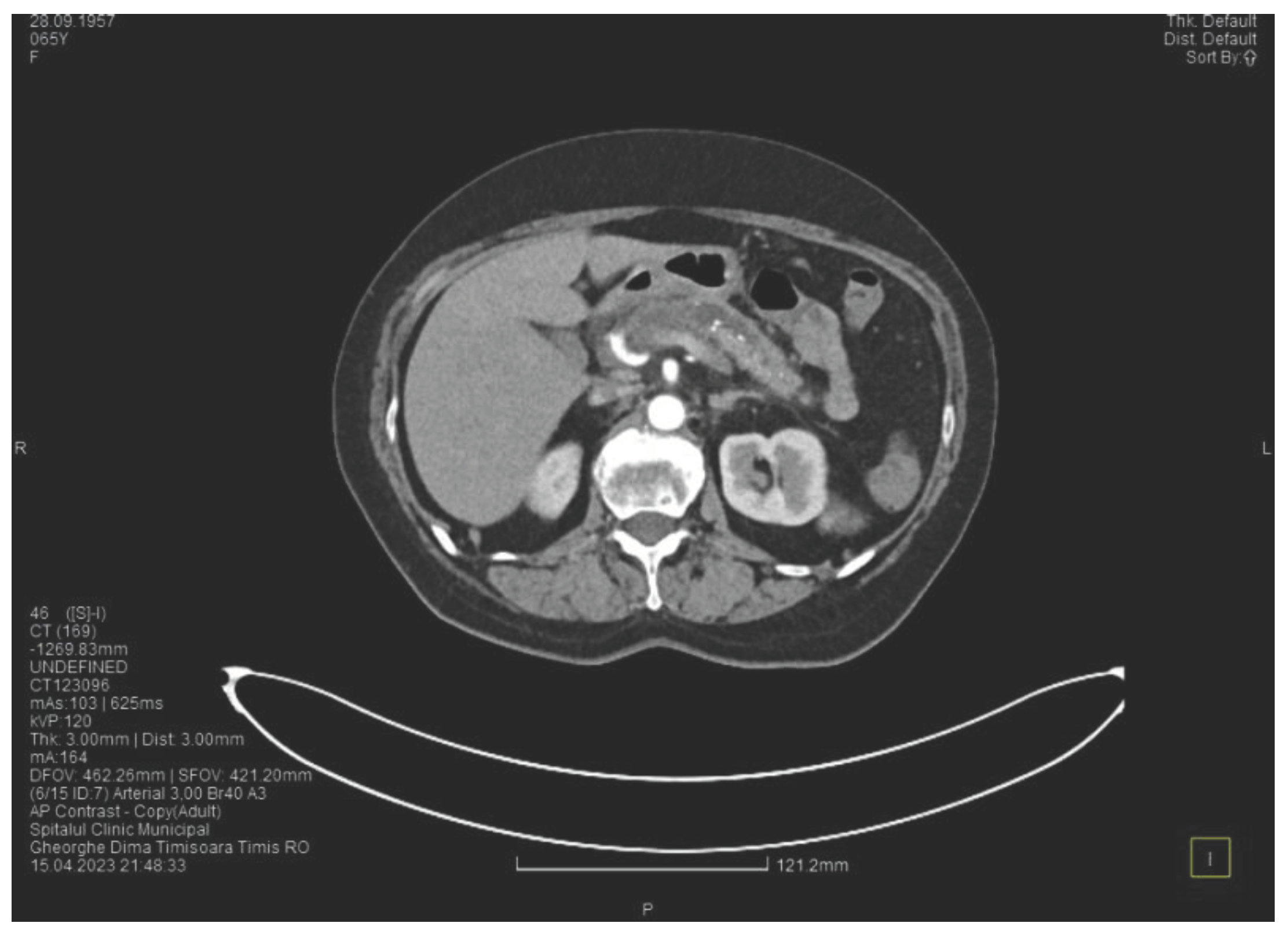

The contrast enhanced computed tomography showed changes suggestive for chronic pancreatitis, with multiple very small calcifications of the pancreatic tissue, a dilatation of the Wirsung duct in the corporeo-caudal area of approximately 15 mm (

Figure 3) and a narrowing of the Wirsung tract in the cephalic area where calcareous conglomerates were present. In the anterior cephalo-uncinate area an oval cyst sized 31/28 mm is detected (larger than one month ago) (

Figure 4). In the peri-cephalo-uncinate area we observed densifications of the adjacent fat extended towards the gastric antrum, the root of the mesentery and the hepatic flexure of the colon. There was a mild inflammatory enlargement of the peripancreatic lymph nodes and of the ons situated in the hepatic hilum. We also noticed a slight dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts and of the common hepatic duct and diffuse atheromatosis of the aorta, the iliac, and the common hepatic arteries. A gastroscopy is performed, which reveals normal esophagus, stomach and duodenal bulb.

We initiated treatment with analgesic and antisecretory drugs and an adequate diet, with the improvement of the symptoms and the discharge of the patient.

Another month later, the patient returned to the emergency department complaining of progressive abdominal pain radiating in the lumbar area, asthenia, and fatigue. The laboratory tests confirmed a new episode of acute pancreatitis (increased serum amylase and lipase – about 7 times higher than the upper normal range), with an elevated C reactive protein, increased alkaline phosphatase and hipopotassemia.

The contrast enhanced computed tomography showed no major changes compared to the one performed one month ago except a more intens peripancreatic inflammation (mainly in the cephalic area).

We initiated treatment with analgesic, antispasmodic, and antisecretory drugs and performed hydroelectrolytic rebalancing, with remission of the symptoms and discharge.

Four months after this episode, the patient presented again in the emergency department complaining of pain in the upper abdomen and postprandial vomiting, symptoms that started approximately 4 weeks ago. During the clinical examination, the abdomen was tender at palpation in the epigastric and the right hypochondriac area, with no signs of peritoneal irritation.

The lab resuts showed sightly increased serum amylase and lipase (about 2 times higher than the upper normal range), mild elevation of transaminases and of blood glucose.

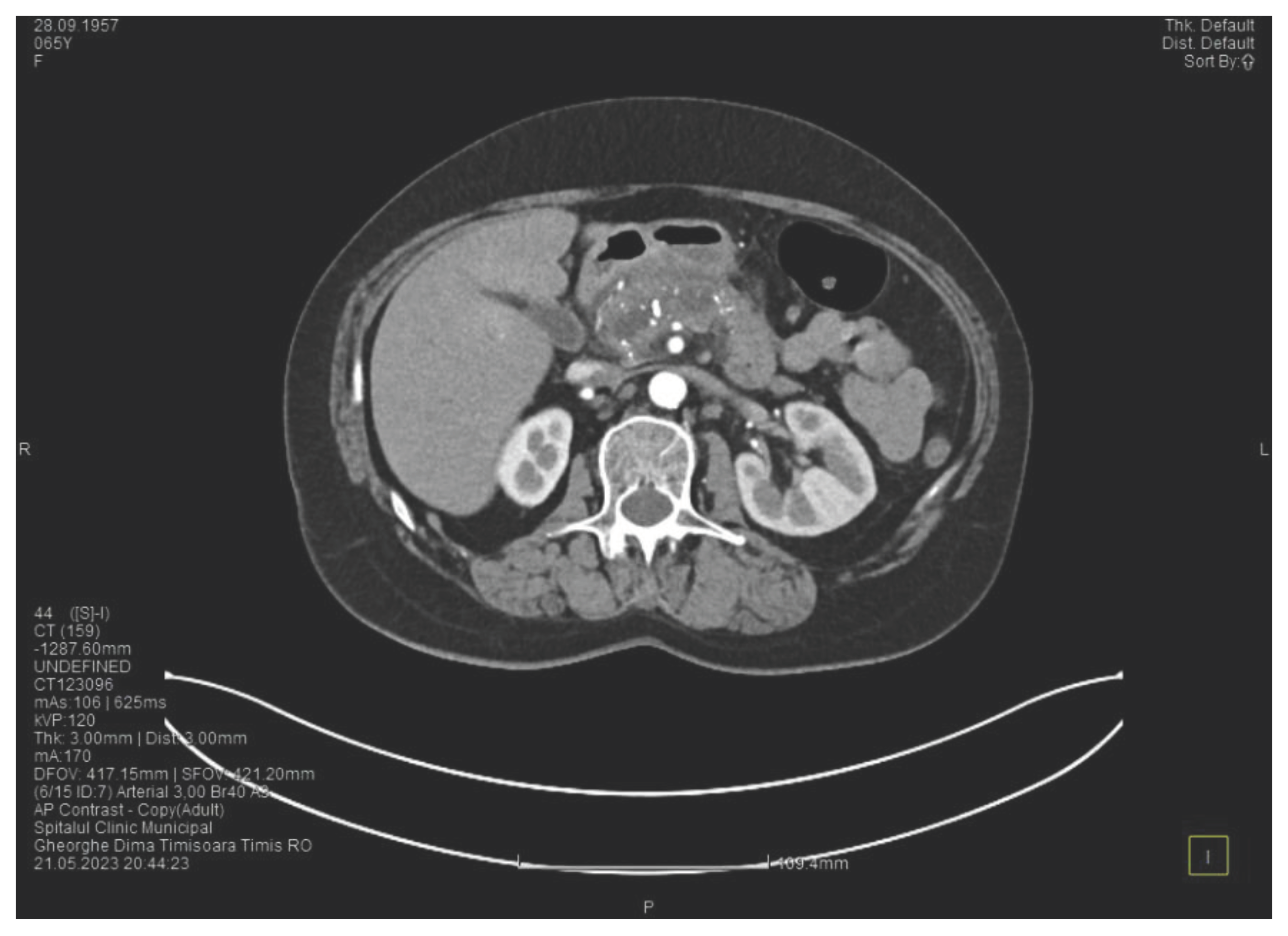

Contrast enhanced computed tomography highlighted signs of chronic pancreatitis with multiple calcifications throughout the pancreatic parenchyma, calcareous conglomerates in the cephalic area (

Figure 6), dilatation of the Wirsung duct of approximately 15 mm, a cephalo-uncinate pseudocyst sized 30/31/32 mm (

Figure 5), densification of the pericephalic pancreatic fat, all the changes being more pronounced compared to the previous examinations. Other findings were acute cholecystitis with thickening of the gallbladder wall and iodophilia of the mucosa, small dilatations of the intrahepatic bile ducts, fluid accumulation in the hepatic hilum and in the periduodenal area, inflammatory wall thickening in the gastric antro-pyloric region and in the duodenum (I, II), and inflammatory lymph nodes in the peripancreatic area and in the hepatic hilum with a size of up to 11 mm.

Figure 5.

CT scan at the fourth episode of acute pancreatitis shows a slightly increased cyst and calcifications in the pancreatic head.

Figure 5.

CT scan at the fourth episode of acute pancreatitis shows a slightly increased cyst and calcifications in the pancreatic head.

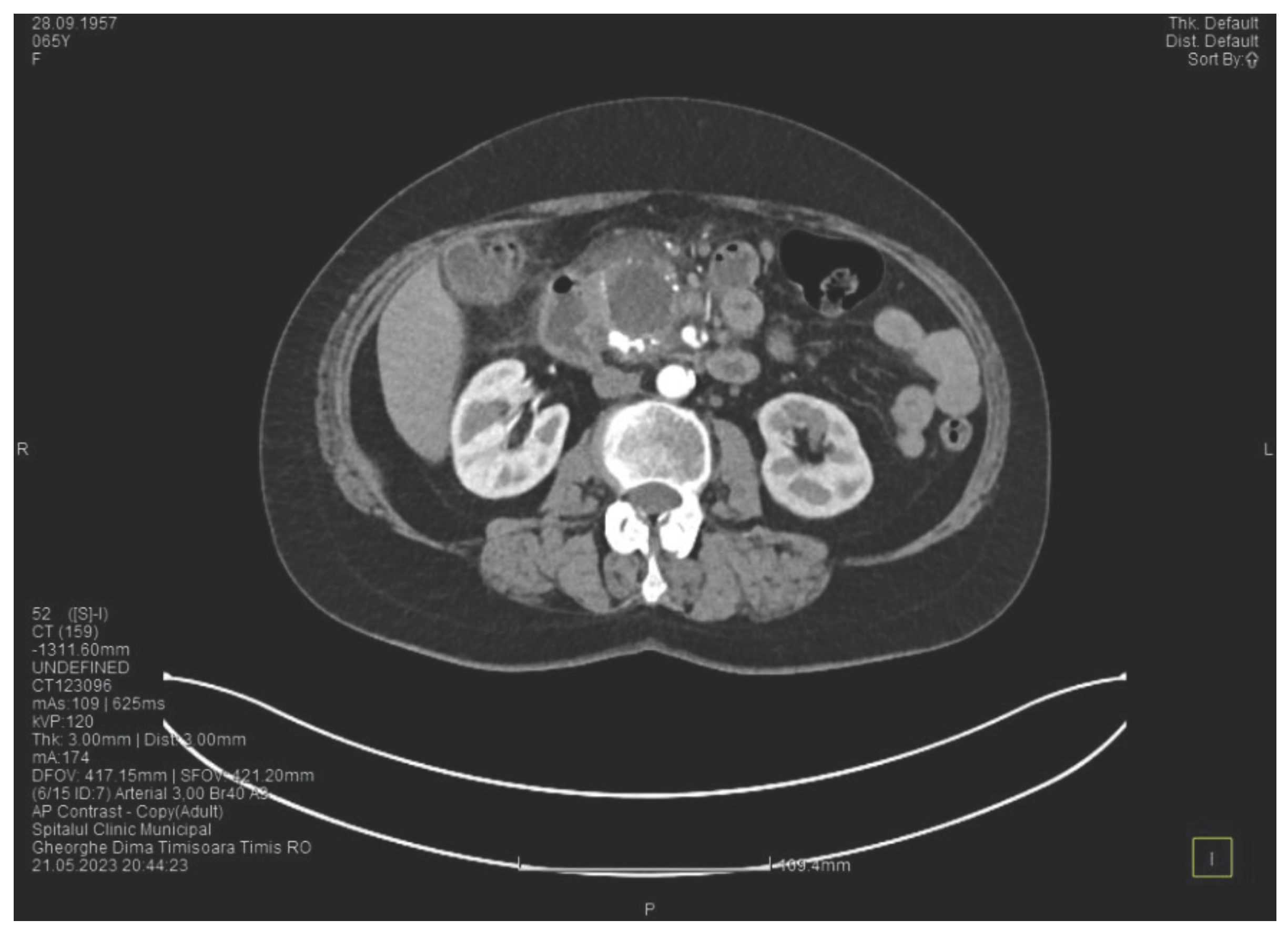

Figure 6.

CT scan at the fourth episode of acute pancreatitis shows calcifications in the pancreatic head, thickening of the duodenal wall and the partial occlusion of the duodenum.

Figure 6.

CT scan at the fourth episode of acute pancreatitis shows calcifications in the pancreatic head, thickening of the duodenal wall and the partial occlusion of the duodenum.

The CT scan showed that the pancreatic changes evolved, with an increase of the cephalic cyst and of the diameter of the pancreatic and biliary ducts. These findings are suggesting the diagnosis of groove pancreatitis since the changes of the pancreas are localized in the head and are externded towards the duodenum, although this disease is quite rare in women. Since most authors consider that the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is challenging and potentially risky, we decided to perform cephalic duodenopancreatectomy, the surgical procedure recommended by most authors.

Another interesting finding before surgery was a slight increase in CA 19-9 (1.5 times higher than the upper normal range).

The surgical procedure was represented by cephalic duodenopancreatectomy with continuous loop reconstruction, which involves end-to-end pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis through intussusception, end to side choledocho-jejunoanastomosis, prosthetic with a Kehr tube and Rachel-Polya type gastrojejunoanastomosis with Braun anastomosis at the base of the loop.

During surgery we noted that the duodenum and the antro-pyloric region were pushed forward, and found wall thickening, inflammation and a partial stenosis of the duodenal lumen, by a cephalo-pancreatic cyst having a diameter of approximately 4 cm. Subsequently, the duodenal dissection was very difficult. We also found inflammation in the hepatic hilum, causing fibrosis, and multiple local adenopathies with a diameter of up to 1 cm. The cystic duct appeared long, dilated, with a parallel path to the main bile duct, and it merges with the main bile duct in the retroduodenal area. The main bile duct presented a normal diameter (7 mm). An interesting finding was that the common hepatic artery did not originate as usual from the celiac trunk but from the superior mesenteric artery and it was partially located in the retropancreatic area. The gallbladder showed important distension, a thin wall and no gallstones. The pancreas presented with fibrosis and multiple calcifications disseminated in the entire parenchyma, mainly in the groove area. The superior mesenteric vein was pulled far to the left by the inflammation, which also affected the transverse mesocolon. When sectioning the pancreatic parenchyma at the isthm, a marked dilatation of the Wirsung duct (1.5 cm) was found.

After surgery, the outcome of the patient was favorable, with no complications, allowing a discharg nine days after surgery. The anatomopathologic examination of the resected piece reveals advanced chronic pancreatitis, with numerous calcifications and cystic lesions having an appearance that varried from cystic mucinous neoplasia with low-degree intraepithelial neoplasia to low-degree intraductal pancreatic neoplasia (PanIN 1 and 2). The anatompathological examination of the lymph nodes showed only inflammation.

Groove pancreatitis is a quite rare disorder, but the case we presented shows some individualizing particularities. The first one is that our patient with groove pancreatitis was a women with tobacco but no alcohol misuse, groove pancreatitis being more frequent in men, usualy with a history of heavy smoking and alcohol misuse. The second particularity is the anatomical abnormality of the common hepatic artery that originated from the superior mesenteric artery and was partially situated behind the pancreas. And the third one is that the anatomopathologic examination showed signs of malignancy, this finding being not common in groove pancreatitis.

Discussions

Described for the first time as a separate entity by Stolte et al., in 1982 [

5], groove pancreatitis remains a condition rarely described in the literature. Between 1990 and 2022 only 1404 cases were presented [

6]. It mainly affects males in their 5

th and 6

th decades of life, with a history of alcohol misuse and heavy smoking. It associates anatomical changes in the duodeno-pancreatic area, such as cystic dysplasia of the heterotopic pancreas, stenosis of the Santorini duct and Brunner gland hyperplasia [

4]. Our case is about a female patient, in her 7

th decade of life, with a long history of heavy smoking, significant weight loss in the last 6 months, presenting at the CT scan cystic dysplasia in the head of the pancreas and diffuse pancreatic calcifications, localized mainly in the pancreatic head. The patient’s symptomatology was characteristic for groove pancreatitis, presenting with recurrent upper abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, most likely in the context of secondary duodenal stenosis.

Groove pancreatitis is classically divided into two forms: the pure form, which strictly affects the groove space, and the segmental form, in which the changes affect the groove space, but extend medially and to the pancreatic head [

2]. In some cases, such as in ours, the changes of chronic pancreatitis can extend to the entire pancreatic parenchyma, a situation revealed by imaging and the result of the histological examination.

Groove pancreatitis is still an underdiagnosed condition with an unknowm real incidence. Recently, along with the improvement of imaging techniques and the publication of radiological criteria, corroborated with the recognition of symptoms, this aspect has improved, as evidenced by the multitude of studies dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of this condition in the last years. The incidence of groove pancreatitis varies between 2.7% and 24.5% in pancreaticoduodenectomies performed for chronic pancreatitis [

7]. In a study conducted on 600 patients resected for chronic pancreatitis, Becker et al. found various degrees of involvement of the groove area in 19.5% of the cases, the pure form being found in 2% of patients, the segmental form in 6.5%, while 11% of the patients showed lesions in the entire pancreatic parenchyma [

8].

The conservative treatment, in most of the cases, is the first-line treatment and is represented by the administration of analgesics, proton pump inhibitors, somatostatin derivatives, pancreatic enzymes, an adequate diet and proper hydration. This approach, according to the published data, may lead to a complete remission of symptoms in only one third of the cases [

2], with frequent episodes of recurrence. In our presented case, the conservative treatment led to the improvement of the patient’s symptoms, but only for short periods of time, being followed by frequent relapses that required several hospitalizations in the last 6 months. This led, besides the impossibility of otherwise excluding a malignant degeneration, to the necessity of surgical treatment.

Endoscopic treatment, whenever possible, is a treatment option for patients with groove pancreatitis, as an alternative to surgical treatment, given the fact that it is less invasive and has lower morbidity. The results of this approach vary from one study to another. While some studies show a success rate of approximately 50%, but with relapses in more than half of the patients [

2,

9,

10], others show a complete remission in 70% of the cases [

11,

12]. Bender et al., in a study conducted on 7 patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, reported extremely poor results, none of the patients presenting a complete remission of symptoms at 6 months, 5 of them requiring surgical intervention [

13]. For the patient we presented, the gastroenterologist of our team evaluated the situation and decided that there were no criteria for an endoscopic treatment.

Surgery remains an important therapeutic approach in groove pancreatitis, especially in cases not responding to conservative treatment or in which pancreatic carcinoma cannot be excluded [

12]. The procedure of choice in groove pancreatitis is pancreaticoduodenectomy, although there are studies in the literature that report alternative procedures, but with contradictory results. Egorov et al., in a study conducted on 84 patients with groove pancreatitis, reported superior results of duodenal resection with pancreas preservation compared to pancreaticoduodenectomy, with a complete remission of symptoms in 93% of cases, compared to 84% in pancreaticoduodenectomy [

14]. The motivation for this type of surgical treatment would be that pancreaticoduodenectomy is too extensive as treatment for the pure form of groove pancreatitis, the least frequent form. Moreover, this approach cannot exclude a pancreatic malignant degeneration, if this suspicion exists. Duodenal or biliary bypass interventions can be useful in case of stenoses [

15], but they address only the complications of pancreatitis and will have limited effects in symptom control. Pancreaticoduodenectomy, with or without pylorus preservation, represents the most used technique for the treatment of groove pancreatitis, presenting a major advantage over all other procedures, where malignant degeneration cannot be excluded. The results of pancreaticoduodenectomy are obviously better than those obtained by conservative or endoscopic treatment, with a high percentage of total remission [

4,

6,

14,

16]. Although it shows the best results, pancreaticoduodenectomy is a major surgical procedure, with mortality at 90 days reaching 5% [

17] and a postoperative morbidity that reaches 45% [

18]. Moreover, the changes produced by the pancreatic and peripancreatic inflammation, which make the dissection much more difficult, can lead to an increased rate of postoperative complications. Considering the fact that a long duration of groove pancreatitis leads to severe inflammation around the pancreas, the best approach would be to perrform pancreaticoduodenectomy as early as possible in case of conservative treatment failure, thus avoiding the potential increase in the risk of complications.

The main challenge in groove pancreatitis is the differentiation from a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Although this differentiation can be extremely difficult without an anatomopathologic examination, Ukegjini et al., in a review including 1404 patients, found some significant criteria that advocate a groove pancreatitis. The factors suggesting groove pancreatitis are: young age, male gender, a history of alcohol misuse and heavy smoking, presentation with pain without jaundice and inflammatory and/or cystic changes in the duodenal wall [

6]. Moreover, one third of the patients with groove pancreatitis showed elevated levels of carcioembrionar antigen and CA 19-9 [

19], making the precise diagnosis more difficult since there is no threshold for this lab tests that could allow the differentiation between the two conditions. The difficult differentiation between the two entities questions the option for conservative treatment, knowing that patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma have a poor prognosis if surgical treatment is delayed. This issue raised difficulties in differential diagnosis also in our case, where, according to the anatomopathologic examination, characteristics of chronic pancreatitis and neoplasia coexist.