Submitted:

18 March 2024

Posted:

20 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Methods

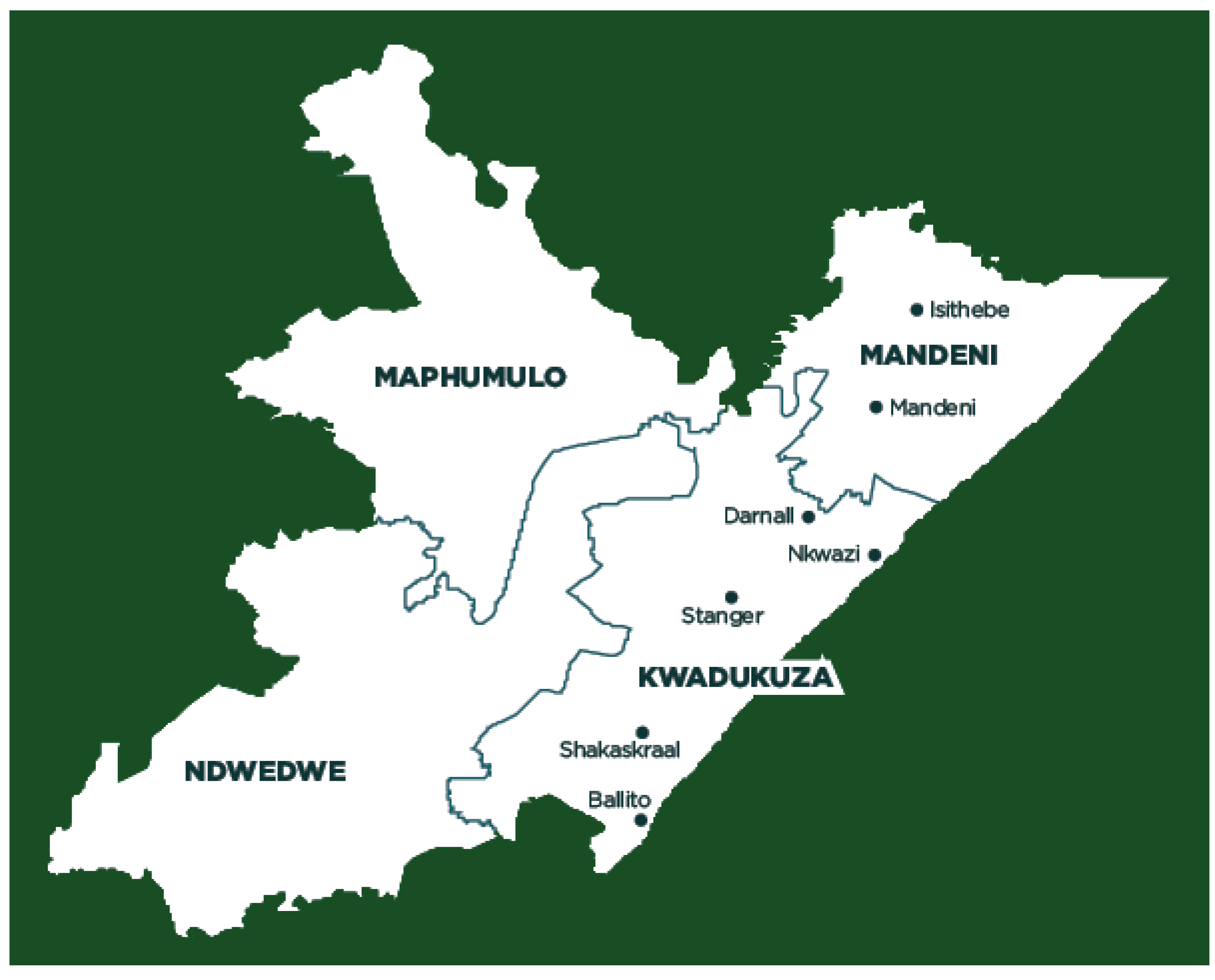

Study Settings

Study Design

Study Sample

Procedure for Recruiting and Selecting Study Participants

Data Collection Methods

Data Analysis

Results

Demographic Details

Traditional Health Practitioners’ Perceptions, Knowledge and Experiences in Diagnosing of FUS.

“… I didn’t just have knowledge of being sangoma (traditional healer), my ancestor came to me and took me to a training of ukuthwasa (which is to accept the calling of becoming a traditional healer).” THP21

“… We use to work up early morning and go to inyanga houses where we had to pass the whole day studying Traditional Medicine and I did it for a year…” THP18

“… If the person is urinating constantly blood or if their urine changing colour. The same thing happens in women when they have this disease (FUS)…” THP18

“ … Urine have unusual temperature, tension on bladder, prostate feels itchy for man, it is swollen near the bladder, and bladder feels pain for male and female. If the person is urinating constantly blood or if their urine changing colour and itching when urinating. The same thing happens in women when they have this disease…” THP2.

“…We perform the practice called Ukumhlola ngoko moya (spiritual divination) to diagnose bilharzia in patients…” THP9

“… Ucama igazi (urinating blood) after swimming in rivers then I throw bones to confirm the diagnostic…” THP15

“I treat the patient who come to me with bilharzia (isichenene) because they think that it is only for children. They are feeling bad to tell to the doctors that they are urinating blood (ukucama igazi)… “THP1

“… I’m not sure of how much it would cost to treat bilharzia at the hospital but traditionally I make the price of all my medicines almost similar, for Ischenene its R150 for the complete treatment…” THP18

“… Traditional healers medicine are quite expensive, traditional healers are more expensive than the scientific people…” THP3

“.. Depends on the person sickness and the person intensity to be healed, as well as what the person need, also on the healer’s payment rate…” THP7

“… We cannot say a patient has to choose what they afford or what they see cheaper between traditional medicine and modern medicine. Doctors’ medicines have chemicals that reduce pains quicker, that’s why I recommend them if I can’t manage the disease…” THP 17

“There are sicknesses that are based on witchcraft, that’s where a traditional healer is needed. When I see that my patient’s sickness is not of witchcraft I then advise them to go to hospitals…” THP21

“… Modern doctors and traditional doctors should work here hand-in-hand. Modern doctors are very important. The collaborative approach is good for the wellbeing of the patient in the managing this disease (FUS)…” THP20

“It is very easy to get these plants. I get them from the forest and I buy some of them from Durban Berea Market…” THP21

“… Yes, we find them easily, depending on experience on using them or got them from other THPs or go at the market… ” THP15

“… Some plants are easy to find while others are very hard to find. I find some plants on the other side of the road and to get others I have to travel to far place …” THP19

“It’s not easy to get these cures because we have to go and look for them in the forest, especially in winter, it is very hard to find them…” THP18

“Patients go to modern doctors most of time on their own initiative, not mine, they go to medical doctors without telling you…” THP8

“… No, concurrent use of traditional and modern medicine unless if TM does not work, the patient himself goes there…” THP16

“… I’m aware that my patients use sometimes both modern and traditional medicine for managing FUS. As traditional healers, it is important for us to work with modern doctors because we are not after money, but we want to see our patients better. There is a stage of the FUS infection that we cannot treat and there are diseases that modern doctors can not treat, so I send my patients there if they need to use both medicines… ” THP21

“… I usually send them to hospitals for checking up if my cure that I used worked or not. Sometimes I send them to Hospital when I don’t know how to treat certain diseases…” THP18

“… No, I don’t mix or allow both uses, but they can rather start with one, if it doesn’t work the patient takes another one. I can do for Lab test but not the treatment because I trust it… Patients use both, but I don’t easily send them to hospitals due to cultural base…” THP12

“… Medical doctors ease the pain but do not permanently remove the problem of FUS…” THP10

“… They do use modern medicine, although doctors don’t really get rid of this infection in women. Only traditional medicine can help get rid of bilharzia…” THP20

“… Yes, there can be some side effects sometimes. It depends on a patient’s health. Some of my treatments can be dangerous if a patient is suffering severely from bilharzia, big quantities cause that, but we lower the dosage to avoid those effects…” THP15

“.. It happens that when a person has bilharzia, he is also having other diseases, but if they manifest after a person has been treated and then I must deal with them too. So, my medicine does not give side effects…” THP20

“… There is no side effect so far. But if there are side effects arising, I would treat them too. If I fail to do so I would take my patient to clinic…” THP22

“… There are no side effects after taking the medicine of treating isichenene. The patient does not go to the toilet a lot and the urine changes back to its normal colour…” THP18

: “… Yes, sometime due to people having different spiritual lives (behaviour of using weather TM or WM with TM combined)…” THP7

Discussion

Limitations of the Study

Conclusion

Funding

Authors’ contributions

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgment

Competing interests

Author’s information

Consent for publication

List of Abbreviations

References

- ADNAN, M. , ULLAH, I., TARIQ, A., MURAD, W., AZIZULLAH, A., KHAN, A. L., ALI, N. J. J. O. E. & Ethnomedicine 2014. Ethnomedicine use in the war affected region of northwest Pakistan. 10, 16. [CrossRef]

- APESOA-VARANO, E. C. & HINTON, L. J. J. O. C.-C. G. 2013. The promise of mixed-methods for advancing Latino health research. 28, 267-282. [CrossRef]

- AREMU, A. , FINNIE, J. & VAN STADEN, J. J. S. A. J. O. B. 2012. Potential of South African medicinal plants used as anthelmintics–Their efficacy, safety concerns and reappraisal of current screening methods. 82, 134-150.

- AREMU, A. O. , MOYO, M., AMOO, S. O. & VAN STADEN, J. J. J. O. E. 2015. Ethnobotany, therapeutic value, phytochemistry and conservation status of Bowiea volubilis: A widely used bulbous plant in southern Africa. 174, 308-316. [CrossRef]

- BAH, S. , DIALLO, D., DEMBÉLÉ, S. & PAULSEN, B. S. J. J. O. E. 2006. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for the treatment of schistosomiasis in Niono District, Mali. 105, 387-399.

- BERGE, S. T. , KABATEREINE, N., GUNDERSEN, S. G., TAYLOR, M., KVALSVIG, J. D., MKHIZE-KWITSHANA, Z., JINABHAI, C., KJETLAND, E. F. J. S. A. J. O. E. & INFECTION 2011. Generic praziquantel in South Africa: the necessity for policy change to provide cheap, safe and effcacious schistosomiasis drugs for the poor, rural population. 26, 22-25. [CrossRef]

- BUWA, L. & VAN STADEN, J. J. J. O. E. 2006. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of traditional medicinal plants used against venereal diseases in South Africa. 103, 139-142.

- CHINSAMY, M. , FINNIE, J. & VAN STADEN, J. J. S. A. J. O. B. 2011. The ethnobotany of South African medicinal orchids. 77, 2-9.

- CHRISTENSEN, M. J. J. O. N. E. & PRACTICE 2017. The empirical-phenomenological research framework: Reflecting on its use. 7, 81. [CrossRef]

- CHRISTINET, V. , LAZDINS-HELDS, J. K., STOTHARD, J. R. & REINHARD-RUPP, J. J. I. J. F. P. 2016. Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS): from case reports to a call for concerted action against this neglected gynaecological disease. 46, 395-404. [CrossRef]

- COCK, I. , SELESHO, M. & VAN VUUREN, S. J. J. O. E. 2018. A review of the traditional use of southern African medicinal plants for the treatment of selected parasite infections affecting humans.

- COLLEY, D. G. , BUSTINDUY, A. L., SECOR, W. E. & KING, C. H. J. T. L. 2014. Human schistosomiasis. 383, 2253-2264.

- CRESWELL, J. W. 2009. Research designs: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- CROUCHER, S. M. & CRONN-MILLS, D. 2014. Understanding communication research methods: A theoretical and practical approach, Routledge.

- DE WET, H. , NZAMA, V. & VAN VUUREN, S. J. S. A. J. O. B. 2012. Medicinal plants used for the treatment of sexually transmitted infections by lay people in northern Maputaland, KwaZulu–Natal Province, South Africa. 78, 12-20.

- FENWICK, A. , WEBSTER, J. P., BOSQUE-OLIVA, E., BLAIR, L., FLEMING, F., ZHANG, Y., GARBA, A., STOTHARD, J., GABRIELLI, A. F. & CLEMENTS, A. J. P. 2009. The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI): rationale, development and implementation from 2002–2008. 136, 1719-1730. [CrossRef]

- GIORGI, A. J. J. O. P. P. 2012. The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. 43, 3-12. [CrossRef]

- GOULD, A. , PENNY, C., PATEL, C. & CANDY, G. J. S. A. J. O. B. 2015. Enhanced cutaneous wound healing by Senecio serratuloides (Asteraceae/Compositae) in a pig model. 100, 63-68. [CrossRef]

- GRACE, O. , SIMMONDS, M., SMITH, G. & VAN WYK, A. J. J. O. E. 2008. Therapeutic uses of Aloe L.(Asphodelaceae) in southern Africa. 119, 604-614. [CrossRef]

- GURARIE, D. , LO, N. C., NDEFFO-MBAH, M. L., DURHAM, D. P. & KING, C. H. J. P. N. T. D. 2018. The human-snail transmission environment shapes long term schistosomiasis control outcomes: Implications for improving the accuracy of predictive modeling. 12, e0006514. [CrossRef]

- HAO, D.-C. , GU, X. & XIAO, P. J. A. P. S. B. 2017. Anemone medicinal plants: ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and biology. 7, 146-158. [CrossRef]

- HUTCHINGS, A. 1996. Zulu medicinal plants: An inventory, University of Natal press.

- HUTCHINGS, A. J. B. 1989. A survey and analysis of traditional medicinal plants as used by the Zulu; Xhosa and Sotho. 19, 112-123. [CrossRef]

- IBTISSEM, B. , ABDELLY, C. & SFAR, S. J. A. C. E. S. 2012. Antioxidant and antibacterial properties of Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Carpobrotus edulis extracts. 2, 359–365. [CrossRef]

- KAMSU-FOGUEM, B. & FOGUEM, C. J. I. M. R. 2014. Adverse drug reactions in some African herbal medicine: literature review and stakeholders’ interview. 3, 126-132. [CrossRef]

- KODURU, S. , GRIERSON, D. & AFOLAYAN, A. J. P. B. 2006. Antimicrobial Activity of Solanum aculeastrum. 44, 283-286. [CrossRef]

- KOENEN, E. V. 2001. Medicinal, poisonous, and edible plants in Namibia, Klaus hess publishers.

- KOMAPE, N. P. M. , ADEROGBA, M., BAGLA, V. P., MASOKO, P., ELOFF, J. N. J. A. J. O. T., COMPLEMENTARY & MEDICINES, A. 2014. Anti-bacterial and anti-oxidant activities of leaf extracts of Combretum vendee (combretecacea) and the isolation of an anti-bacterial compound. 11, 73-77. [CrossRef]

- KRIPPENDORFF, K. J. H. C. R. 2004. Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. 30, 411-433. [CrossRef]

- KUCKARTZ, U. 2012. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung, Beltz Juventa.

- LAZARUS, R. S. 2006. Stress and emotion: A new synthesis, Springer Publishing Company.

- LINCOLN, Y. S. & GUBA, E. G. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverley Hills. ca: sage.

- MAGAISA, K. , TAYLOR, M., KJETLAND, E. F. & NAIDOO, P. J. J. S. A. J. O. S. 2015. A review of the control of schistosomiasis in South Africa. 111, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- MANDER, M. , NTULI, L., DIEDERICHS, N. & MAVUNDLA, K. J. S. A. H. R. 2007. Economics of the traditional medicine trade in South Africa: health care delivery. 2007, 189-196.

- MANGOYI, R. , MUKANGANYAMA, S. J. T. A. J. O. P. S. & BIOTECHNOLOGY 2011. In vitro antifungal activities of selected medicinal plants from Zimbabwe against Candida albicans and Candida krusei. 5, 1-7.

- MAROYI, A. J. J. O. E. 2013. Traditional use of medicinal plants in south-central Zimbabwe: review and perspectives. J Journal of ethnobiology andethnomedicine, 9, 31. [CrossRef]

- MARSHALL, M. N. J. B. 1998. Qualitative study of educational interaction between general practitioners and specialists. 316, 442-445. [CrossRef]

- MAYRING, P. 2015. Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical background and procedures. Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education. Springer. [CrossRef]

- MOKGOBI, M. J. A. J. F. P. H. E., RECREATION, 2013. Towards integration of traditional healing and western healing: Is this a remote possibility? J African journal for physical health education, recreation,dance, 2013, 47.

- MOKOKA, T. A., MCGAW, L. J., MDEE, L. K., BAGLA, V. P., IWALEWA, E. O., ELOFF, J. N. J. B. C. & MEDICINE, A. 2013. Antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of triterpenes isolated from leaves of Maytenus undata (Celastraceae). 13, 111. [CrossRef]

- MUYA, K. , TSHOTO, K., CIOCI, C., ASEHO, M., KALONJI, M., BYANGA, K., KALONDA, E. & SIMBI, L. J. P. 2014. Survol ethnobotanique de quelques plantes utilisées contre la schistosomiase urogénitale à Lubumbashi et environs. 12, 213-228.

- NAIDOO, D. , VAN VUUREN, S., VAN ZYL, R. & DE WET, H. J. J. O. E. 2013. Plants traditionally used individually and in combination to treat sexually transmitted infections in northern Maputaland, South Africa: antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity. 149, 656-667.

- NKOMO, M. , NKEH-CHUNGAG, B. N., KAMBIZI, L., NDEBIA, E. J., IPUTO, J. E. J. A. J. O. P. & PHARMACOLOGY 2010. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties of Gunnera perpensa (Gunneraceae). 4, 263-269.

- NLOOTO, M. , NAIDOO, P. J. B. C. & MEDICINE, A. 2016. Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use by HIV patients a decade after public sector antiretroviral therapy roll out in South Africa: a cross sectional study. 16, 128. [CrossRef]

- NXUMALO, N. , ALABA, O., HARRIS, B., CHERSICH, M. & GOUDGE, J. J. J. O. P. H. P. 2011. Utilization of traditional healers in South Africa and costs to patients: findings from a national household survey. 32, S124-S136. [CrossRef]

- OJEWOLE, J. A. J. J. O. E. 2006. Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic properties of Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch. & CA Mey.(Hypoxidaceae) corm [‘African Potato’] aqueous extract in mice and rats. 103, 126-134. [CrossRef]

- PATTON, M. Q. 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods, SAGE Publications, inc.

- PEEK, P. M. 1991. African divination systems: Ways of knowing, Georgetown University Press.

- PELTZER, K. , FRIEND-DU PREEZ, N., RAMLAGAN, S., FOMUNDAM, H., ANDERSON, J. J. A. J. O. T., COMPLEMENTARY & MEDICINES, A. 2010. Traditional complementary and alternative medicine and antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV patients in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. 7.

- POGGENSEE, G. , FELDMEIER, H. & KRANTZ, I. J. P. T. 1999. Schistosomiasis of the female genital tract: public health aspects. 15, 378-381. [CrossRef]

- POOLEY, B. J. D. N. F. P. T. P.-C. I. I. X. E. I., MAPS. GEOG 1998. A field guide to wild flowers of KwaZulu-Natal and the eastern region. 5.

- POPAT, A. , SHEAR, N. H., MALKIEWICZ, I., STEWART, M. J., STEENKAMP, V., THOMSON, S. & NEUMAN, M. G. J. C. B. 2001. The toxicity of Callilepis laureola, a South African traditional herbal medicine. 34, 229-236. [CrossRef]

- REIDPATH, D. D. , ALLOTEY, P., POKHREL, S. J. H. R. P. & SYSTEMS 2011. Social sciences research in neglected tropical diseases 2: A bibliographic analysis. 9, 1. [CrossRef]

- SAATHOFF, E. , OLSEN, A., MAGNUSSEN, P., KVALSVIG, J. D., BECKER, W. & APPLETON, C. C. J. B. I. D. 2004. Patterns of Schistosoma haematobium infection, impact of praziquantel treatment and re-infection after treatment in a cohort of schoolchildren from rural KwaZulu-Natal/South Africa. 4, 40.

- SEMENYA, S. S. , POTGIETER, M. J. J. J. O. E. & ETHNOMEDICINE 2014. Bapedi traditional healers in the Limpopo Province, South Africa: their socio-cultural profile and traditional healing practice. 10, 4. [CrossRef]

- SPARG, S. , VAN STADEN, J. & JÄGER, A. J. J. O. E. 2000. Efficiency of traditionally used South African plants against schistosomiasis. 73, 209-214. [CrossRef]

- SPARG, S. , VAN STADEN, J. & JÄGER, A. J. J. O. E. 2002. Pharmacological and phytochemical screening of two Hyacinthaceae species: Scilla natalensis and Ledebouria ovatifolia. 80, 95-101. [CrossRef]

- STANIFER, J. W. , PATEL, U. D., KARIA, F., THIELMAN, N., MARO, V., SHIMBI, D., KILAWEH, H., LAZARO, M., MATEMU, O. & OMOLO, J. J. P. O. 2015. The determinants of traditional medicine use in northern Tanzania: a mixed-methods study. 10, e0122638. [CrossRef]

- SYLLA, A. J. S. D. P. , ECOLE NATIONALE DE MÉDECINE ET DE PHARMACIE DU MALI, BAMAKO 1991. Contributiona l’inventaire des Antibilharziens et Molluscicides Traditionnels dans le cercle de Kayes.

- TABA, M. , FAKOYA, M. J. J. O. A. & MANAGEMENT 2016. COST ACCOUNTING PRACTICES IN AFRICAN TRADITIONAL HEALING: A CASE STUDY OF MAKHUDUTHAMAGA TRADITIONAL HEALERS IN SOUTH AFRICA. 6, 75-88.

- TAYLOR, J. & VAN STADEN, J. J. P. G. R. 2001. The effect of age, season and growth conditions on anti-inflammatory activity in Eucomis autumnalis (Mill.) Chitt. Plant extracts. 34, 39-47.

- VAN WYK, B.-E., HEERDEN, F. V. & OUDTSHOORN, B. V. 2002. Poisonous plants of South Africa, Briza Publications.

- VIGNERON, M. , DEPARIS, X., DEHARO, E. & BOURDY, G. J. J. O. E. 2005. Antimalarial remedies in French Guiana: a knowledge attitudes and practices study. 98, 351-360. [CrossRef]

- WATT, J. M. , BREYER-BRANDWIJK, M. G. J. T. M., SOUTHERN, P. P. O., MEDICINAL, E. A. B. A. A. O. T., OTHER USES, C. C., PHARMACOLOGICAL EFFECTS, MAN, T. I. & ANIMAL. 1962. The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa being an Account of their Medicinal and other Uses, Chemical Composition, Pharmacological Effects and Toxicology in Man and Animal.

- WHO, W. H. O. 2011. Helminth control in school-age children: a guide for managers of control programmes, Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO, W. H. O. 2015. Investing to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: third WHO report on neglected tropical diseases 2015, World Health Organization.

- WHO, W. H. O. 2018. Schistosomiasis, Fact Sheet No 115. Available at http://www. who. int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en. Last accessed on 12 December 2018, 12 December.

- YINEGER, H. , KELBESSA, E., BEKELE, T. & LULEKAL, E. J. J. O. M. P. R. 2013. Plants used in traditional management of human ailments at Bale Mountains National Park, Southeastern Ethiopia. 2, 132-153.

- ZUMA, T. , WIGHT, D., ROCHAT, T., MOSHABELA, M. J. B. C. & MEDICINE, A. 2016. The role of traditional health practitioners in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: generic or mode specific? 16, 304.

| Variables | Category | No. | % | Proportion (95% Confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

Female Male |

14 | 63.6 | 40.7 – 82.8 |

| 8 | 36.4 | 17.2 – 59.3 | ||

|

Marital status |

Married Not married |

14 | 63.6 | 40.7 – 82.8 |

| 8 | 36.4 | 17.2 – 59.3 | ||

| Level of Education | High School completed None specified Prim. School completed Postsecondary certificate Degree |

10 | 45.5 | 24.4 – 67.8 |

| 7 | 31.8 | 13.9 – 54.9 | ||

| 3 | 13.6 | 2.9 -34.9 | ||

| 1 | 4.5 | 0.1 – 22.8 | ||

| 1 | 4.5 | 0.12 – 22.8 | ||

|

Profession |

Diviner (Sangoma) Both (Sangoma/Inyanga) Herbalist (Inyanga) |

17 | 77.2 | 54,6 - 92,2 |

| 3 | 13.6 | 2,9 – 34,9 | ||

| 2 | 9.1 | 1.1 – 29.2 | ||

|

Religion |

Christian Traditional religion Hinduism None specified |

15 | 68.2 | 45.1 – 86.1 |

| 5 | 22.7 | 7.8 – 45.4 | ||

| 1 | 4.5 | 0.1 – 22.8 | ||

| 1 | 4.5 | 0.1 – 22.8 | ||

| Mean years of work experience, SD: 13 (10.170) Age (years) Mean age, SD, Range: 41.05 (13.075), 26 – 70 | ||||

| Botanical name | Family |

isiZulu (Z)/isiXhosa (X), Tshivenda (V) vernacular name (s) given by interviewees | Number of times quoted by THPs | Previous report of ethnomedical uses (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenostemma caffrum DC. | Asteraceae | Umahogo (Z) | 1 | Used as love charm and for influenza. The infusion is taken as an emetic given to children as enemas (Hutchings, 1996). |

| Albuca fastigiata Dryand. | Hyacinthaceae | uMaphipha (Z) | 1 | Traditionally used as emetics for protection against sorcery and as general protective charms (Pooley, 1998). |

|

Aloe marlothii A.Berger/ Aloe ferox Mill. |

Asphodelaceae | iNhlaba, uMhlaba (Z) | 2 | Used in southern African for infections, particularly sexually transmitted infections and internal parasites, genito-urinary system, , injuries, digestion, pregnancy, skin complaints, sensory system, inflammation, pain, respiratory system, muscular–skeletal system, nutrition (Grace et al., 2008). |

|

Anemone fanninii Harv. ex Mast. |

Ranunculaceae | Emyama/ nManzamnyama (Z) | 1 | The plant has antitumor, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, sedative, analgesic activities, anti-convulsant and anti-histamine effects (Hao et al., 2017). |

|

Bowiea volubilis Harv. Ex Hook.f. subsp. volubilis |

Hyacinthaceae | UGibisisila or uGibisila; iguleni (Z); uMgaqana (X) | 2 | Plant widely used against numerous ailments including headache, muscular pains, infertility, cystitis and venereal diseases in southern Africa (Aremu et al., 2015). |

|

Callilepis laureola DC. |

Asteraceae | Amafuthomhlaba, ihlamvu, impila (Z) | 2 | Used for stomach problems, tape worm infestations, impotence, cough, and to induce fertility. Impila is also administered to pregnant women by traditional birth attendants to “ensure the health of the mother and child” and to facilitate labor. It is also taken by young girls in the early stages of menstruation (Popat et al., 2001). |

| Carpobrotus edulis (L.) L.Bolus | Mesembryanthemaceae (Aizoaceae) | mthombozi/Umgongozi (Z) | 1 | The plant is used in soothing itching caused by spider and tick bites. It contains astringent antiseptic juice which can be taken orally for treating sore throat and mouth infections. It has a antimicrobial activity (Ibtissem et al., 2012) |

| Combretum erythrophyllum (Burch.) Sond. | Combretaceae |

Umdubu (Z) | 1 | Used for the treatment of abdominal pains and venereal diseases due to antibacterial compounds in the leaves (Hutchings, 1996). |

| Combretum vendae A.E.van Wyk | Combretaceae | Gopo (gopo-gopo, gopokopo-bani (V). | 1 | Used for the treatment of bacterial related infections and oxidative related diseases by indigenous people of South Africa (Komape et al., 2014). |

| Eucomis autumnalis (Mill.) Chitt. | Hyacinthaceae | uBuhlungu eSimathunzi (X), uMathunga (Z) | 4 | Greatly valued in traditional medicine for the treatment of a variety of ailments, predominantly those involving pain, fever and inflammation (Taylor and Van Staden, 2001). |

|

Gunnera perpensa L. |

Gunneraceae | iPhuzi lomlambo, iGhobo (X); uGobhe, uGobho (Z) |

4 | Used in folk medicine to relieve rheumatoid pain, facilitate childbirth and healing wounds. Zulu traditional healers use it to induce labor, expel the placenta after birth and to relief menstrual pains (Nkomo et al., 2010). |

|

Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch., C.A.Mey. & Avé-Lall. |

Hypoxidaceae | iNkomfe (Z), iLabatheka (Xhosa) | 5 | Southern African ‘wonder’ plant medicine being claimed to be an effective remedy against HIV/AIDS-related diseases, arthritis, yuppie flu, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cancer, psoriasis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, tuberculosis, urinary tract infections, asthma, and some central nervous system (CNS) disorders, especially epilepsy and childhood convulsions (Ojewole, 2006). |

| Knowltonia bracteata Harv. ex J.Zahlbr. | Ranunculaceae | nguthuza or uMvuthuza (Z) | 1 | Used for sexually transmitted diseases (Buwa and Van Staden, 2006). |

| Maytenus undata (Thunb.) Blakelock | Celastraceae | Undubula /iNdabulaluvalo (Z) | 2 | Widely used in folk medicine as anti-tumour, anti-asthmatic, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and anti-ulcer agents, and as a treatment for stomach problems (Mokoka et al., 2013). |

|

Myrothamnus flabellifolius Welw. |

Myrothamnaceae | uVuka kwa bafile (Z) | 2 | Used for respiratory ailments, nosebleeds and fainting, alleviate backache, kidney problems, haemorrhoids and menstrual pains, abrasions , dressings for burns and wounds, chest pains and asthma, treat infections and pains in the uterus. In central Africa it is used as a tonic and to treat breast complaints. Shona healers have used the plant to treat epilepsy, madness and coughs (Van Wyk et al., 2002). |

| Nidorella Sp. Schimper, G.W. | Asteraceae | uMhlabelo | 2 | Useful in embrocation for fractures, sprains and snakebites (Hutchings, 1996). |

| Ranunculus multifidus Forssk, | Ranunculaceae | Uxhaphozi (Z) | 1 | It used for sexually transmitted infections (De Wet et al., 2012) |

| Rhoicissus sp. Wild & R.B.Drumm), | Vitaceae | iSinwazi (Z) | 4 | Medicinal plants used to treat burns, swelling and malaria, one can expect that they might possess anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory activities as well (Hutchings, 1996). |

| Sclerocarya birrea (A.Rich.) Hochst. | Anacardiaceae | umGanu (Z) | 1 | It is used in treating proctitis. The Vhavenda use it to treat fevers, stomach ailments and ulcers and for many purposes including sore eyes in Zimbabwe. In East Africa, it is an ingredient in an alcoholic medicine taken to treat an internal ailment known as kati, it is used for stomach disorders. The Hausas in West Africa use it as a remedy for dysentery. It could show that extracts inhibit diarrhoea in mice (Mokoka et al., 2013). |

|

Senecio serratuloides var. gracilis Harv., |

Asteraceae | uNsukumbili (Z) | 7 | Traditional herbal remedy used to treat skin wounds in South Africa (Gould et al., 2015). |

| Solanum aculeastrum Dunal subsp. aculeastrum | Solanaceae | Imbuna/iNtuma and water |

1 | Plant used in traditional medicine to treat various human and animal diseases, specifically stomach disorders and various cancers, in the Eastern Cape, South Africa (Koduru et al., 2006). |

| Tylophora flanaganii Schltr. | Apocynaceae | iNhlanhlemhlophe (iNhlanhla) (Z) | 4 | It is taken in Asia and Africa for allergies, asthma, cancer, congestion, constipation, cough, inflamed skin, diarrhoea, bloody diarrhoea, gas, haemorrhoids, tender joints (gout), yellowed skin (jaundice), joint disorder (rheumatoid arthritis), whooping cough, to make someone vomit, and to cause sweating (Hutchings, 1989). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).