Submitted:

20 March 2024

Posted:

21 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Extraction

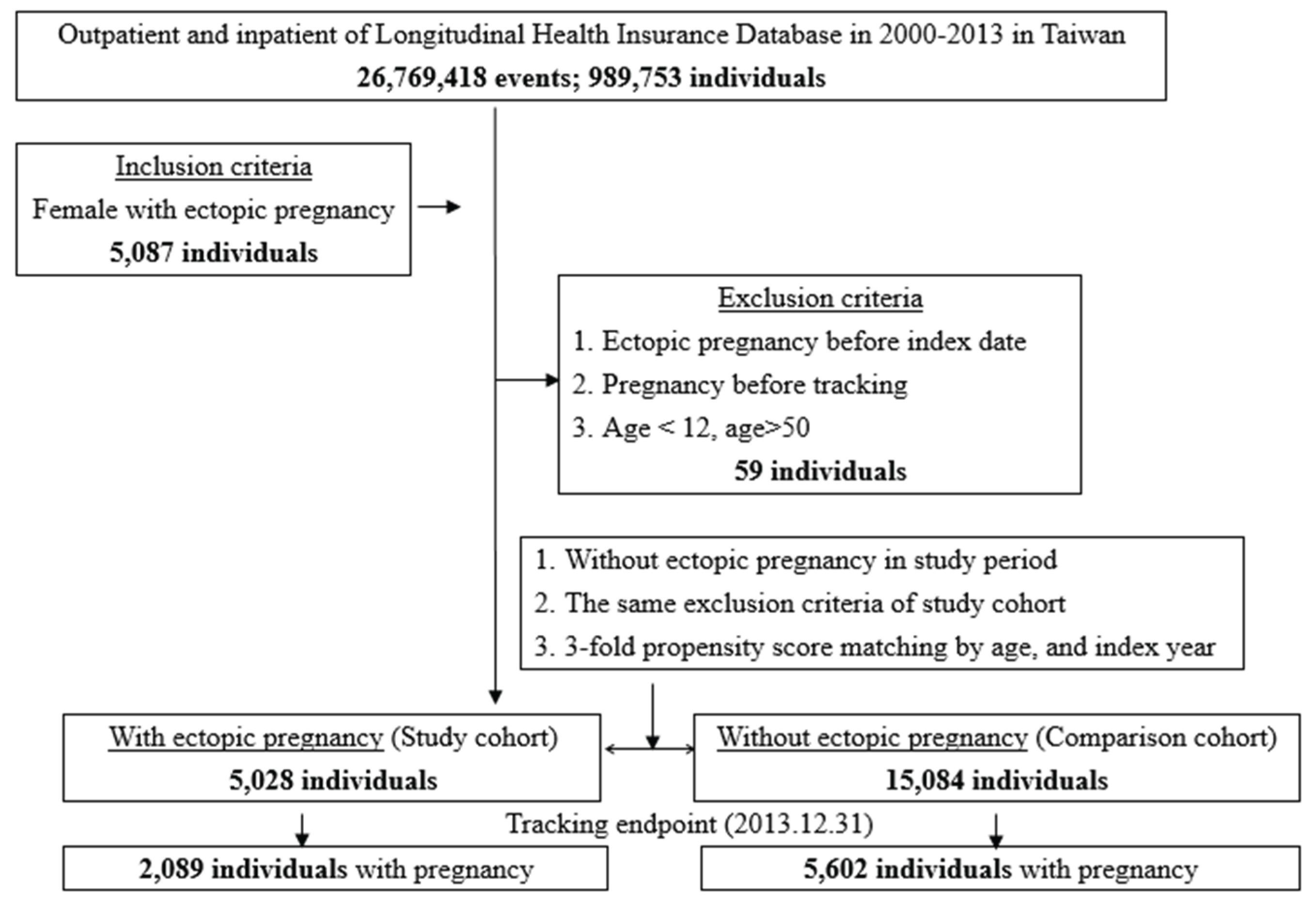

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grimes, D.A. The morbidity and mortality of pregnancy: still risky business. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994, 170, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Berg, C.J.; Herndon, J.; Flowers, L.; Seed, A.K.; Syverson, C.J. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance—United States, 1991—1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2003, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ehrenberg-Buchner, S.; Sandadi, S.; Moawad, N.S.; Pinkerton, J.S.; Hurd, W.W. Ectopic pregnancy: role of laparoscopic treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009, 52, 372–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyer, J.; Fernandez, J.C.; Pouly, J.L; Job-Spira, N. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10 year population-base study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod. 2002, 17, 3224–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barash, J.H. , Buchanan, E. M., Hillson, C. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2014, 90, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, C. M Ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 2005, 366, 583–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Fawad, A.; Shah, A.A.; Jadoon, H.; Sarwar, I.; Abbasi, A.U.N. Analysis of two years cases of ectopic pregnancy. 2017, 29, 65-67.

- The world factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/birth-rate/ (accessed on 12th Jan, 2024).

- National health insurance administration, ministry of health and welfare. Available online: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/Content_List.aspx?n= 34D1C9E227F442B7&topn=4864A82710DE35ED (accessed on 12th Jan, 2024).

- Chouinard, M.; Mayrand, M.H.; Ayoub, A.; Healy-Profitos, J.; Auger, N. Ectopic pregnancy and outcomes of future intrauterine pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2019, 112, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duz, S.A. Fertility outcomes after medical and surgical management of tubal ectopic pregnancy. Acta Clin Croat. 2022, 60, 347–353. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, M.I.; Tang, C.H.; Hsu, P.Y.; Huang, Y.T.; Long, C.Y.; Huang, K.H; Wu, M.P. Primary and repeated surgeries for ectopic pregnancies and distribution by patient age, surgeon age, and hospital levels: an 11-year nationwide population-based descriptive study in Taiwan. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012, 19, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhus, L.L.; Egerup, P.; Skovlund, C.W.; Lidegaard, Ø. Long-term reproductive outcomes in women whose first pregnancy is ectopic: a national controlled follow-up study. Hum Reprod. 2013, 28, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhus, L.L.; Egerup, P.; Skovlund, C.W.; Lidegaard, Ø. Impact of ectopic pregnancy for reproductive prognosis in next generation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014, 93, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeber, B.E.; Barnart, K.T. Suspected ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006, 107, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.A. An international survey of the health economics of IVF and ICSI. Hum Reprod Update. 2002, 8, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics Executive Yuan. Available online: http://ebook.dgbas.gov.tw/public/data/352913302353.pdf (accessed on 12th Jan, 2024).

- Xue, Y.; Tong, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S. Pregnancy outcomes following in vitro fertilization treatment in women with previous recurrent ectopic pregnancy. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0272949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Mol, B.W.; Li, P.; Liu, X.; Watrelot, A.; Shi, J. Tubal factor infertility with prior ectopic pregnancy: a double whammy? A retrospective cohort study of 2,892 women. Fertil Steril. 2020, 113, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.D.; Scaper, A.M.; Rooney, B. Reproductive outcome after 143 laparoscopic procedures for ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1993, 81, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hsu, J.Y.; Chen, L.; Gumer, A.R.; Tergas, A.I.; Hou, J.Y.; Burke, W.M.; Ananth, C.V.; Hershman, D.L.; Wright, J.D. Disparities in the management of ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017, 217, 49.e1–49e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.; McLernon, D.J.; Lee, A.J.; Bhattacharya, S. Reproductive outcomes following ectopic pregnancy: register-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, L.A.; Mikkelsen, E.M.; Sørensen, H.T.; Rothman, K.J.; Hahn, K.A.; Riis, A.H.; Hatch, E.E. Prospective study of time to pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2015, 103, 1065–1073e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, K.T. Clinical practice. Ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009, 361, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, H.; Capmas, P.; Lucot, J.P.; Resch, B.; Panel, P.; Bouyer, J. Fertility after ectopic pregnancy: the DEMETER randomized trial. Hum Reprod. 2013, 28, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ectopic pregnancy | Total | With | Without | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 20,112 | 5,028 | 25.00 | 15,084 | 75.00 | ||

| Pregancy | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 12,421 | 61.76 | 2,939 | 58.45 | 9,482 | 62.86 | |

| With | 7,691 | 38.24 | 2,089 | 41.55 | 5,602 | 37.14 | |

| Age (years) | 33.73±8.12 | 33.17±7.09 | 33.91±8.43 | <0.001 | |||

| Age group (years) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 12-19 | 434 | 2.16 | 95 | 1.89 | 339 | 2.25 | |

| 20-29 | 6,647 | 33.05 | 1,639 | 32.60 | 5,008 | 33.20 | |

| 30-39 | 9,021 | 44.85 | 2,494 | 49.60 | 6,527 | 43.27 | |

| ≧40 | 4,010 | 19.94 | 800 | 15.91 | 3,210 | 21.28 | |

| Insured premium (NT$) | 0.828 | ||||||

| <18,000 | 18,000 | 89.50 | 4,498 | 89.46 | 13,502 | 89.51 | |

| 18,000-34,999 | 1,569 | 7.80 | 399 | 7.94 | 1,170 | 7.76 | |

| ≧35,000 | 543 | 2.70 | 131 | 2.61 | 412 | 2.73 | |

| Anemia | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 20,001 | 99.45 | 4,982 | 99.09 | 15,019 | 99.57 | |

| With | 111 | 0.55 | 46 | 0.91 | 65 | 0.43 | |

| Shock | 0.407 | ||||||

| Without | 20,016 | 99.52 | 5,008 | 99.60 | 15,008 | 99.50 | |

| With | 96 | 0.48 | 20 | 0.40 | 76 | 0.50 | |

| Season | 0.306 | ||||||

| Spring | 4,816 | 23.95 | 1,207 | 24.01 | 3,609 | 23.93 | |

| Summer | 5,169 | 25.70 | 1,246 | 24.78 | 3,923 | 26.01 | |

| Autumn | 5,227 | 25.99 | 1,315 | 26.15 | 3,912 | 25.93 | |

| Winter | 4,900 | 24.36 | 1,260 | 25.06 | 3,640 | 24.13 | |

| Location | 0.019 | ||||||

| Northern Taiwan | 8,715 | 43.33 | 2,252 | 44.79 | 6,463 | 42.85 | |

| Middle Taiwan | 5,352 | 26.61 | 1,297 | 25.80 | 4,055 | 26.88 | |

| Southern Taiwan | 4,945 | 24.59 | 1,194 | 23.75 | 3,751 | 24.87 | |

| Eastern Taiwan | 1,029 | 5.12 | 274 | 5.45 | 755 | 5.01 | |

| Outlets islands | 71 | 0.35 | 11 | 0.22 | 60 | 0.40 | |

| Urbanization level | <0.001 | ||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 7,614 | 37.86 | 1,970 | 39.18 | 5,644 | 37.42 | |

| 2 | 8,558 | 42.55 | 2,180 | 43.36 | 6,378 | 42.28 | |

| 3 | 1,568 | 7.80 | 371 | 7.38 | 1,197 | 7.94 | |

| 4 (The lowest) | 2,372 | 11.79 | 507 | 10.08 | 1,865 | 12.36 | |

| Level of care | <0.001 | ||||||

| Hospital center | 6,219 | 30.92 | 1,468 | 29.20 | 4,751 | 31.50 | |

| Regional hospital | 6,319 | 31.42 | 1,535 | 30.53 | 4,784 | 31.72 | |

| Local hospital | 7,574 | 37.66 | 2,025 | 40.27 | 5,549 | 36.79 | |

| P: Chi-square/Fisher exact test on category variables and t-test on continue variables | |||||||

| Variables | Crude HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ectopic pregnancy | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 1.265 | 1.203 | 1.331 | <0.001 | 1.160 | 1.103 | 1.220 | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 12-19 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 20-29 | 1.662 | 1.359 | 2.033 | <0.001 | 1.589 | 1.299 | 1.945 | <0.001 |

| 30-39 | 0.597 | 0.569 | 0.853 | <0.001 | 0.689 | 0.563 | 0.844 | <0.001 |

| ≧40 | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.024 | <0.001 |

| Insured premium (NT$) | ||||||||

| <18,000 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 18,000-34,999 | 0.828 | 0.650 | 1.055 | 0.127 | 0.961 | 0.820 | 1.126 | 0.622 |

| ≧35,000 | 0.818 | 0.609 | 1.083 | 0.157 | 1.621 | 1.272 | 2.067 | <0.001 |

| Anemia | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 0.982 | 0.714 | 1.351 | 0.912 | 0.973 | 0.707 | 1.339 | 0.866 |

| Shock | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 0.000 | - | - | 0.774 | 0.000 | - | - | 0.691 |

| Season | ||||||||

| Spring | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Summer | 0.966 | 0.906 | 1.031 | 0.301 | 0.974 | 0.912 | 1.039 | 0.418 |

| Autumn | 0.977 | 0.917 | 1.041 | 0.471 | 1.003 | 0.942 | 1.069 | 0.917 |

| Winter | 1.044 | 0.978 | 1.114 | 0.189 | 0.981 | 0.920 | 1.047 | 0.565 |

| Location | ||||||||

| Northern Taiwan | Reference | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | ||||||

| Middle Taiwan | 0.981 | 0.929 | 1.036 | 0.490 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Southern Taiwan | 0.941 | 0.889 | 0.996 | 0.035 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Eastern Taiwan | 0.905 | 0.815 | 1.004 | 0.059 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Outlets islands | 1.328 | 0.937 | 1.880 | 0.111 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Urbanization level | ||||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 1.044 | 0.969 | 1.125 | 0.255 | 1.136 | 1.050 | 1.228 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 1.077 | 1.001 | 1.158 | 0.046 | 1.031 | 0.958 | 1.110 | 0.413 |

| 3 | 0.991 | 0.896 | 1.096 | 0.857 | 0.852 | 0.770 | 0.943 | 0.002 |

| 4 (The lowest) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Level of care | ||||||||

| Hospital center | 0.469 | 0.443 | 0.497 | <0.001 | 0.715 | 0.673 | 0.760 | <0.001 |

| Regional hospital | 0.513 | 0.487 | 0.541 | <0.001 | 0.749 | 0.710 | 0.790 | <0.001 |

| Local hospital | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| HR= hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, Adjusted HR: Adjusted variables listed in the table | ||||||||

| Ectopic pregnancy | With | Without | With vs. Without | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strarified | Event | PYs | Rate (per 105 PYs) | Event | PYs | Rate (per 105 PYs) | Ratio | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P |

| Total | 2,089 | 49,353.69 | 4,232.71 | 5,602 | 178,041.29 | 3,146.46 | 1.345 | 1.160 | 1.103 | 1.220 | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | |||||||||||

| 12-19 | 41 | 422.70 | 9,699.49 | 56 | 1,149.21 | 4,872.93 | 1.990 | 1.798 | 1.176 | 2.750 | 0.007 |

| 20-29 | 1,033 | 9,903.66 | 10,430.48 | 3,155 | 32,214.43 | 9,793.75 | 1.065 | 1.028 | 0.957 | 1.103 | 0.450 |

| 30-39 | 982 | 19,797.57 | 4,960.21 | 2,322 | 62,651.24 | 3,706.23 | 1.338 | 1.303 | 1.209 | 1.405 | <0.001 |

| ≧40 | 33 | 19,229.76 | 171.61 | 69 | 82,026.41 | 84.12 | 2.040 | 1.986 | 1.308 | 3.016 | 0.001 |

| Insured premium (NT$) | |||||||||||

| <18,000 | 2,019 | 47,750.86 | 4,228.20 | 5,450 | 173,269.24 | 3,145.39 | 1.344 | 1.153 | 1.095 | 1.214 | <0.001 |

| 18,000-34,999 | 49 | 1,206.55 | 4,061.15 | 107 | 3,585.47 | 2,984.26 | 1.361 | 1.574 | 1.099 | 2.254 | 0.013 |

| ≧35,000 | 21 | 396.28 | 5,299.29 | 45 | 1,186.58 | 3,792.43 | 1.397 | 0.937 | 0.525 | 1.673 | 0.826 |

| Anemia | |||||||||||

| Without | 2,074 | 49,028.66 | 4,230.18 | 5,570 | 177,213.40 | 3,143.10 | 1.346 | 1.157 | 1.100 | 1.218 | <0.001 |

| With | 15 | 325.03 | 4,615.02 | 32 | 827.89 | 3,865.24 | 1.194 | 1.539 | 0.703 | 3.369 | 0.281 |

| Shock | |||||||||||

| Without | 2,089 | 49,151.33 | 4,250.14 | 5,602 | 177,050.14 | 3,164.08 | 1.343 | 1.160 | 1.103 | 1.220 | <0.001 |

| With | 0 | 202.36 | 0.00 | 0 | 991.15 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Season | |||||||||||

| Spring | 463 | 11,424.42 | 4,052.72 | 1,301 | 40,184.78 | 3,237.54 | 1.252 | 1.117 | 1.004 | 1.243 | 0.043 |

| Summer | 498 | 11,961.81 | 4,163.25 | 1,405 | 46,093.50 | 3,048.15 | 1.366 | 1.086 | 0.980 | 1.204 | 0.117 |

| Autumn | 595 | 13,710.05 | 4,339.88 | 1,517 | 50,167.17 | 3,023.89 | 1.435 | 1.241 | 1.128 | 1.366 | <0.001 |

| Winter | 533 | 12,257.42 | 4,348.39 | 1,379 | 41,595.84 | 3,315.24 | 1.312 | 1.187 | 1.073 | 1.314 | 0.001 |

| Urbanization level | |||||||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 725 | 18,016.60 | 4,024.07 | 1,957 | 61,005.16 | 3,207.93 | 1.254 | 1.096 | 1.008 | 1.195 | 0.035 |

| 2 | 950 | 21,881.68 | 4,341.53 | 2,492 | 77,532.01 | 3,214.16 | 1.351 | 1.181 | 1.095 | 1.273 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 173 | 4,374.48 | 3,954.76 | 469 | 15,865.11 | 2,956.17 | 1.338 | 1.232 | 1.033 | 1.470 | 0.020 |

| 4 (The lowest) | 241 | 5,080.93 | 4,743.23 | 684 | 23,639.00 | 2,893.52 | 1.639 | 1.196 | 1.031 | 1.388 | 0.019 |

| Level of care | |||||||||||

| Hospital center | 428 | 15,301.51 | 2,797.11 | 1,277 | 57,203.35 | 2,232.39 | 1.253 | 1.106 | 0.991 | 1.235 | 0.072 |

| Regional hospital | 568 | 17,620.83 | 3,223.46 | 1,555 | 65,240.51 | 2,383.49 | 1.352 | 1.172 | 1.064 | 1.291 | 0.001 |

| Local hospital | 1,093 | 16,431.35 | 6,651.92 | 2,770 | 55,597.43 | 4,982.24 | 1.335 | 1.192 | 1.111 | 1.280 | <0.001 |

| PYs = Person-years; Adjusted HR = Adjusted Hazard ratio: Adjusted for the variables listed in Table 3.; CI = confidence interval | |||||||||||

| Ectopic pregnancy (With vs. Without) | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the tracking of X year(s) | ||||

| 1 | 0.360 | 0.317 | 0.409 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.674 | 0.627 | 0.724 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.789 | 0.741 | 0.840 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 0.886 | 0.816 | 0.918 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 0.921 | 0.871 | 0.975 | 0.004 |

| 6 | 0.975 | 0.923 | 1.031 | 0.376 |

| 7 | 0.983 | 0.932 | 1.037 | 0.531 |

| 8 | 1.020 | 0.967 | 1.076 | 0.463 |

| 9 | 1.042 | 0.989 | 1.099 | 0.124 |

| 10 | 1.075 | 1.021 | 1.132 | 0.006 |

| 11 | 1.113 | 1.057 | 1.172 | <0.001 |

| 12 | 1.129 | 1.072 | 1.198 | <0.001 |

| 13 | 1.148 | 1.091 | 1.208 | <0.001 |

| 14 (Total) | 1.160 | 1.103 | 1.220 | <0.001 |

| HR= hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, Adjusted HR: Adjusted variables listed in Table 2. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).