Submitted:

20 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

1.2. Historical Perspective

1.3. Goal of Current Review

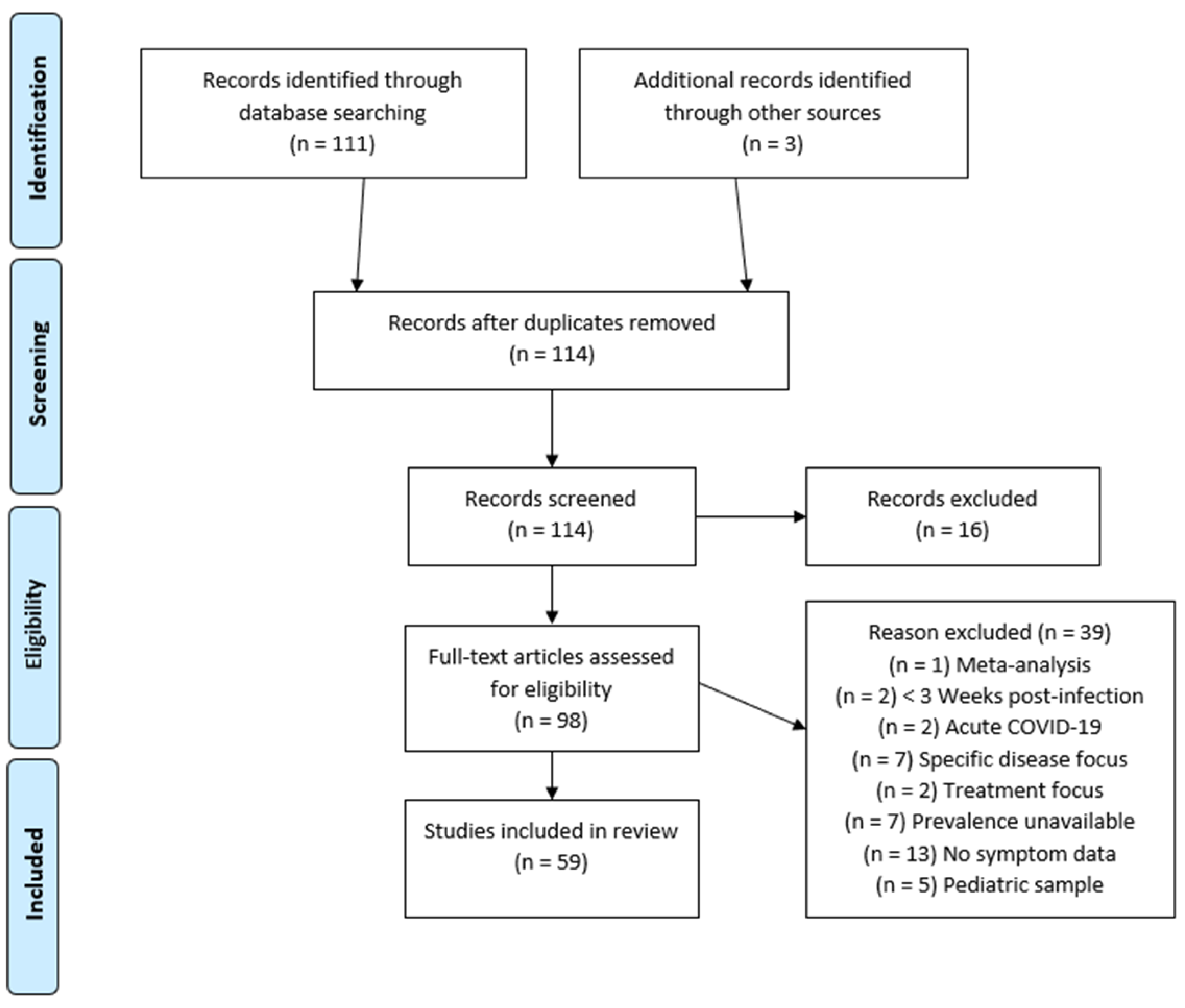

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Article Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. PASC Symptom Categories

2.4. PASC Symptom Reporting

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Statistical Methods

3. Results

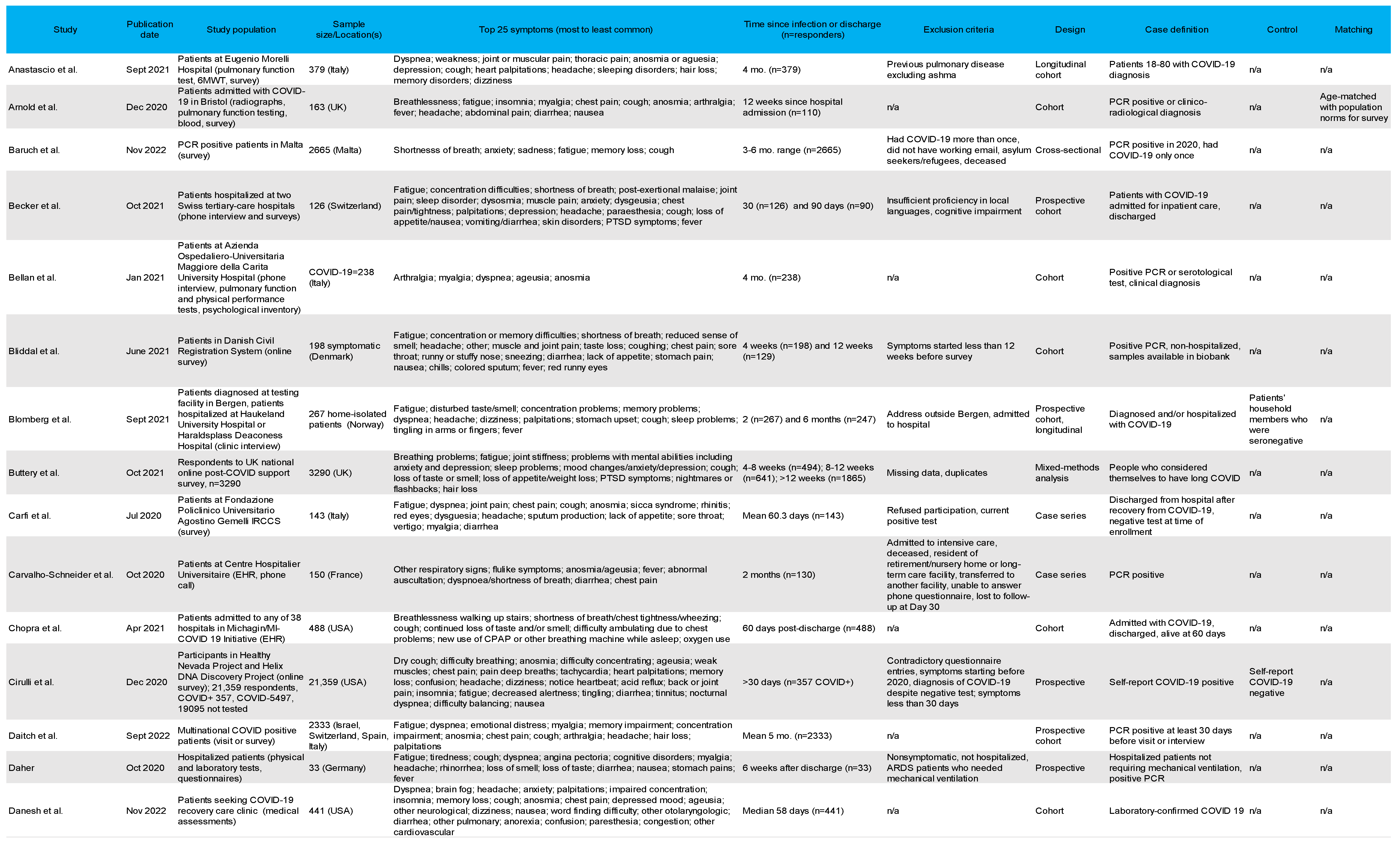

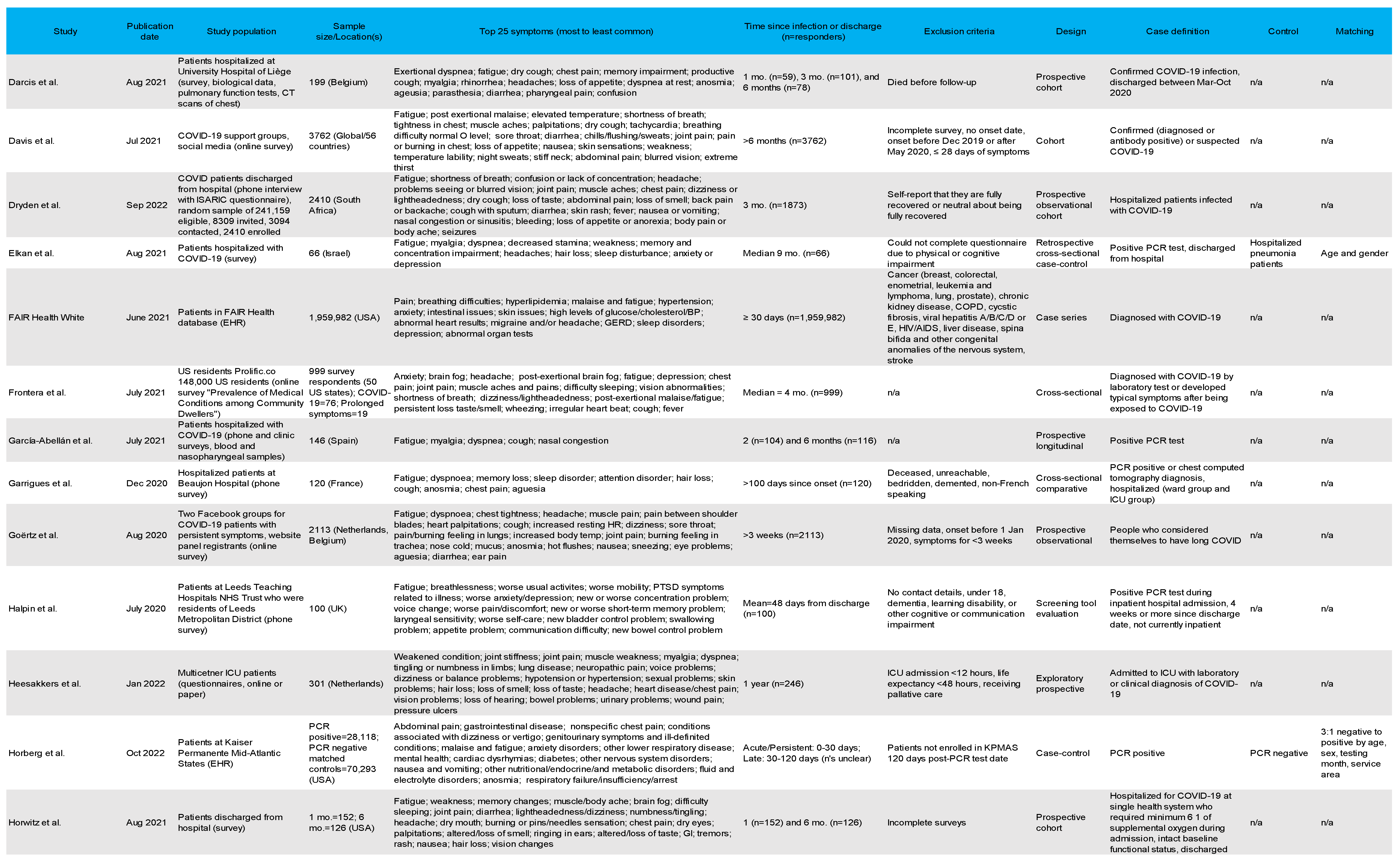

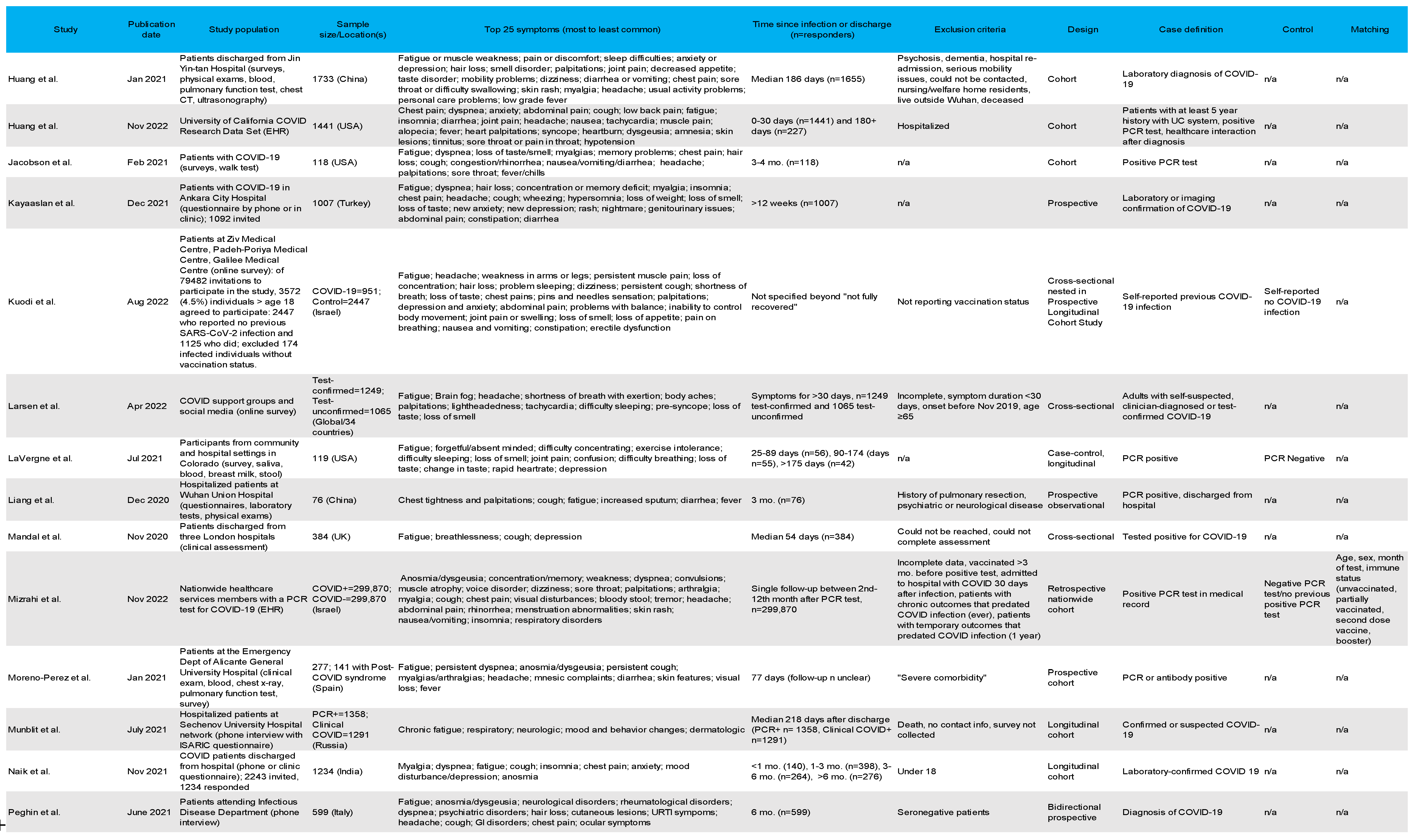

3.1. Population Characteristics

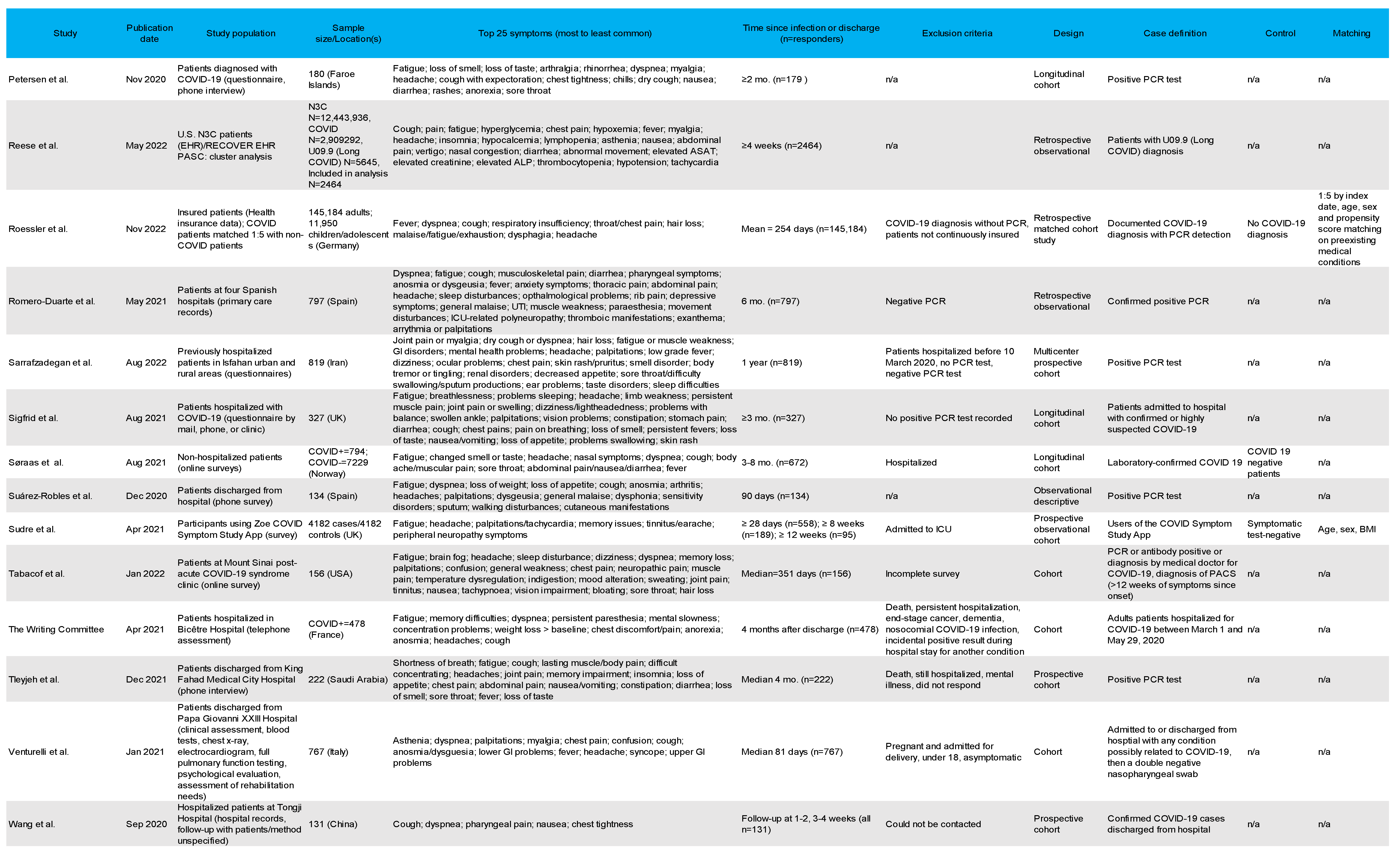

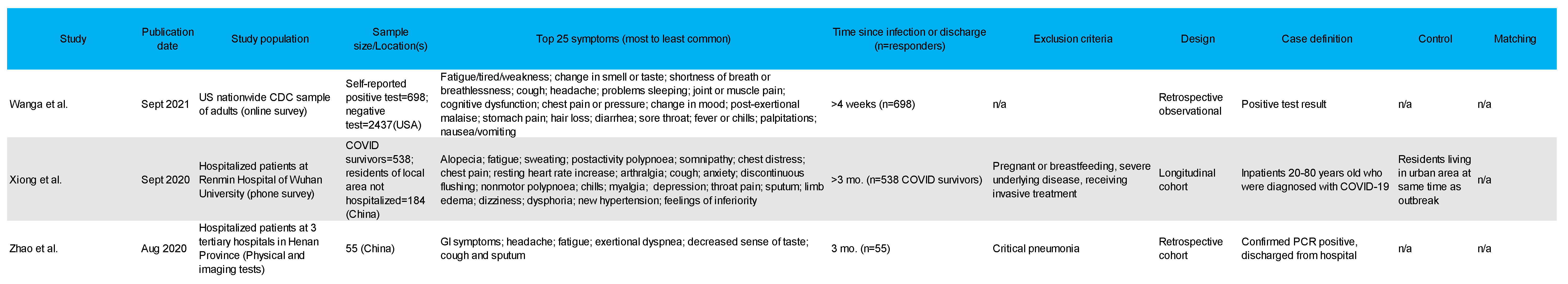

3.2. Study Designs and Case Definitions

3.3. Definitions of PASC

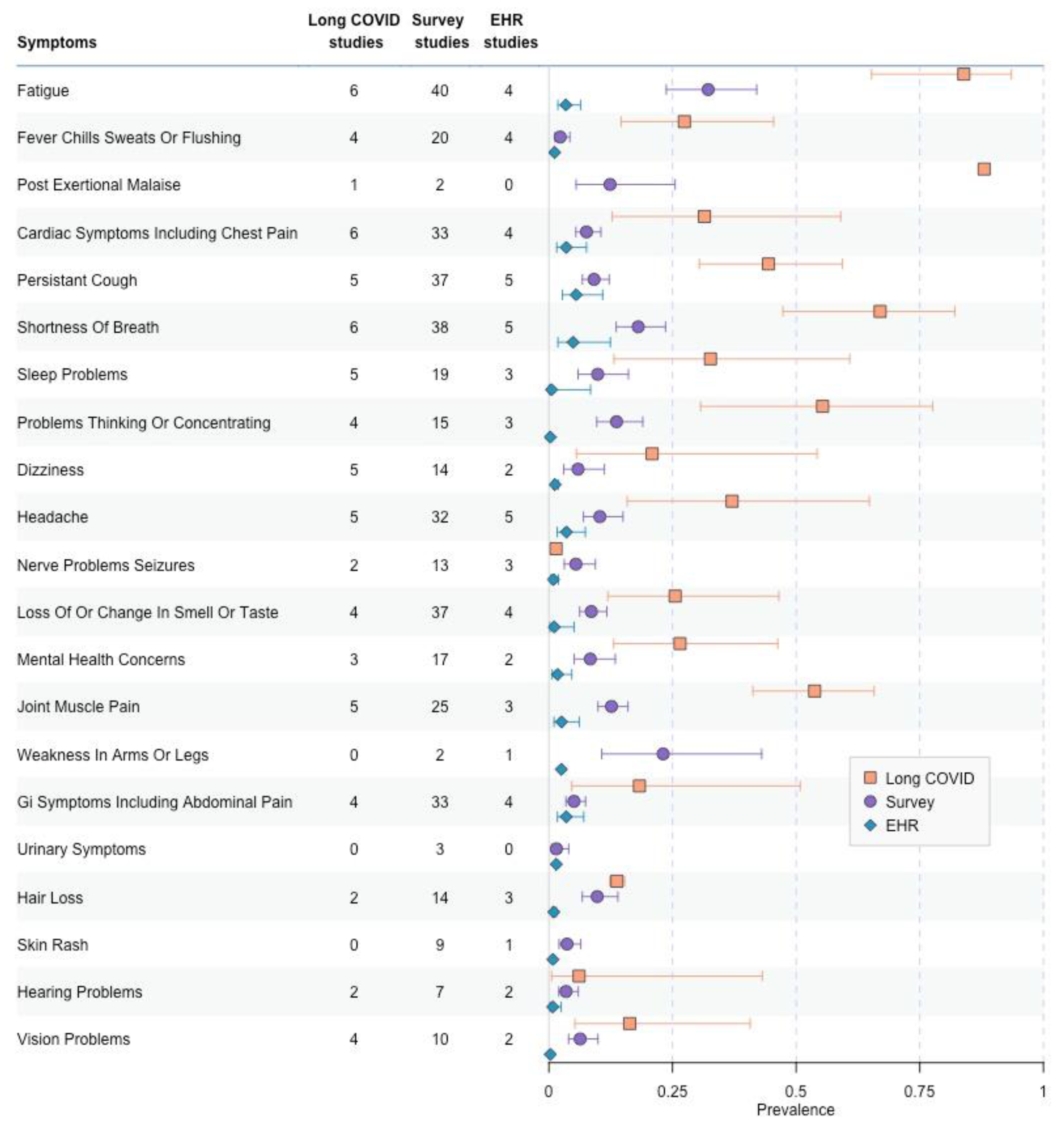

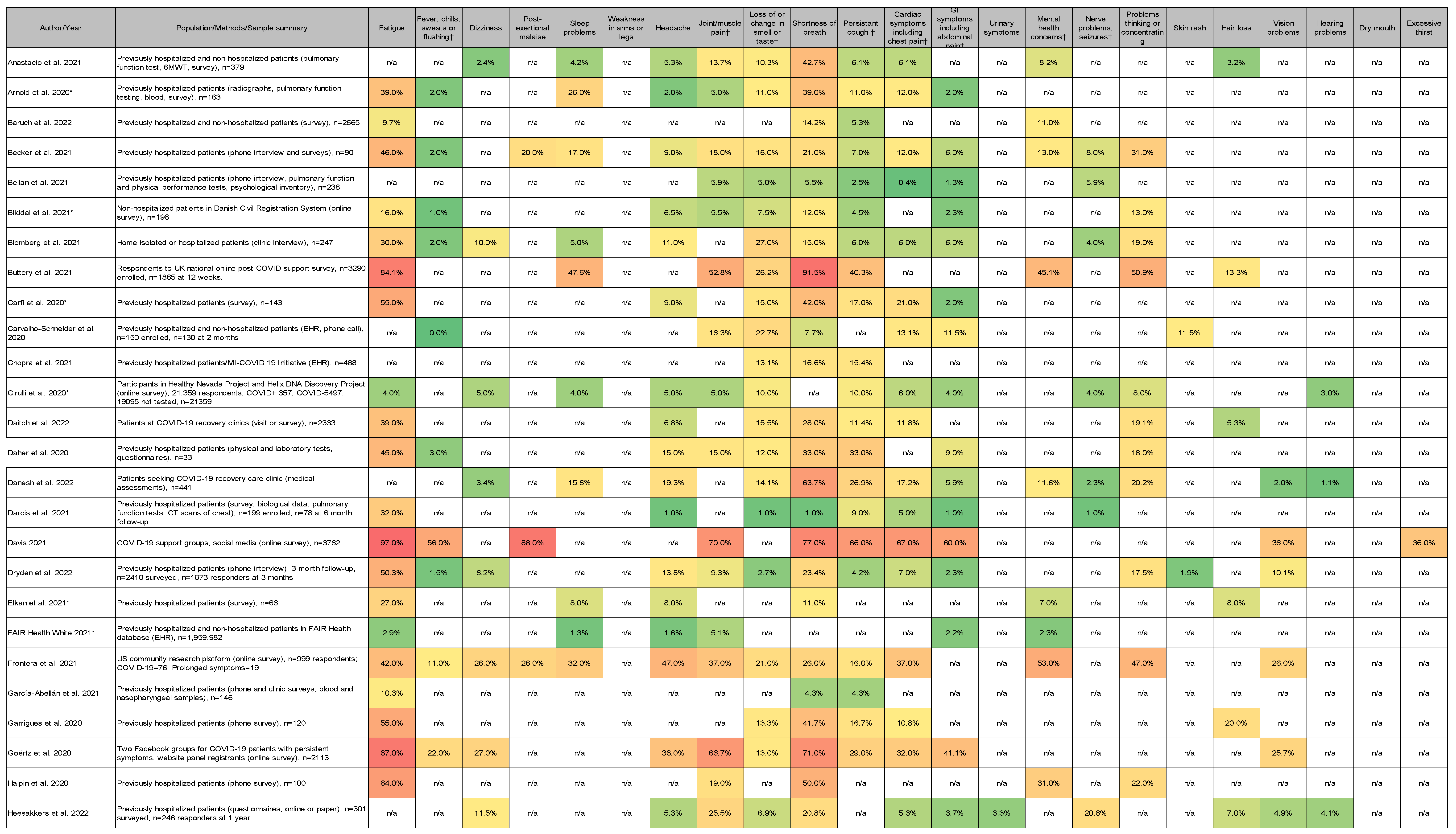

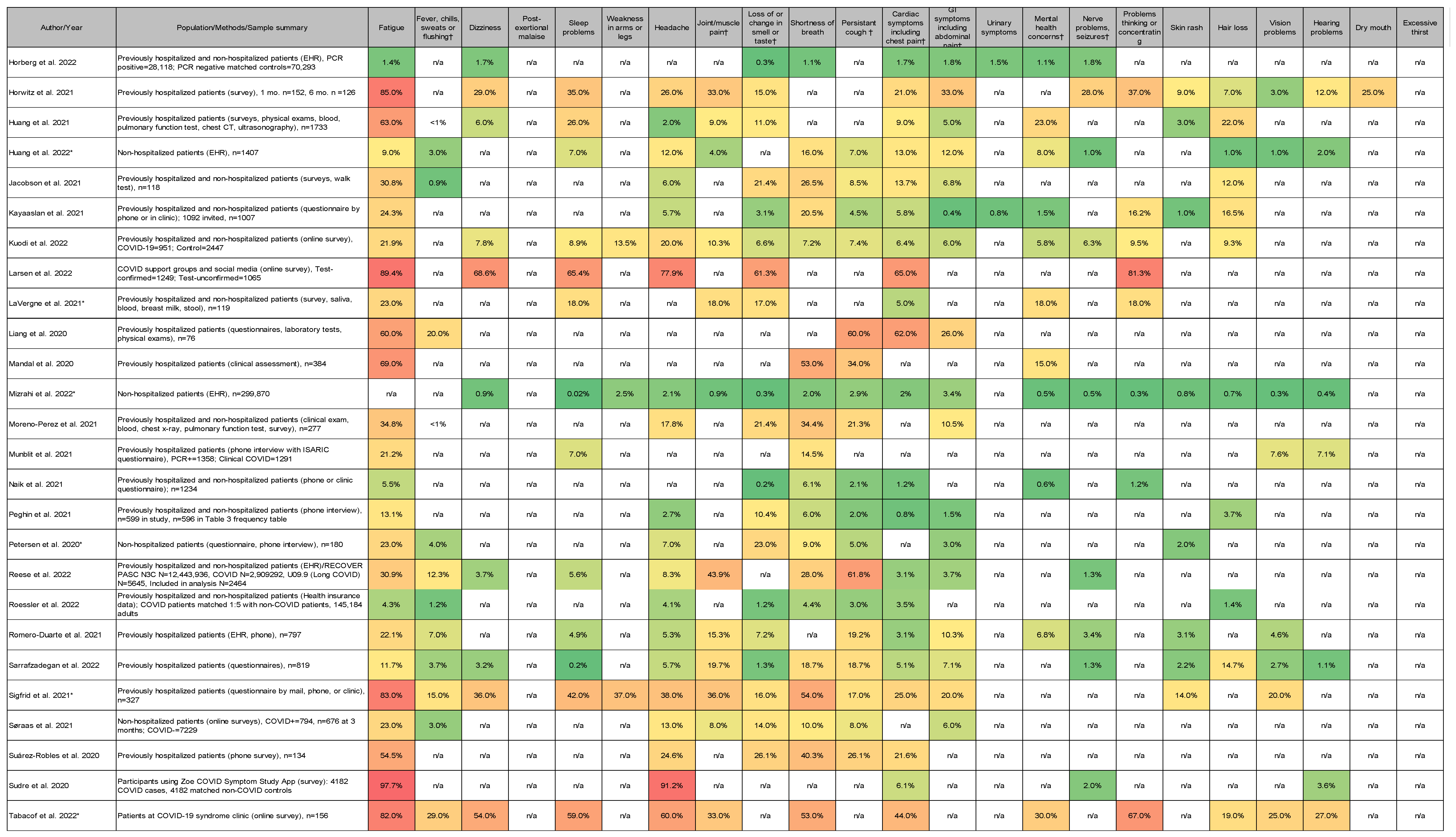

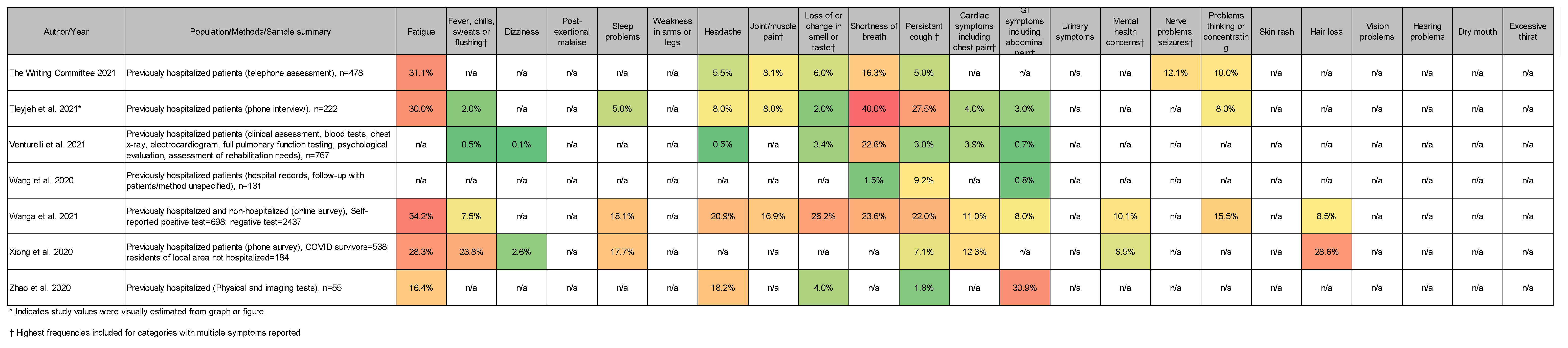

3.4. Most Common Symptoms Reported across 59 Studies

3.5. Data Collection Methods

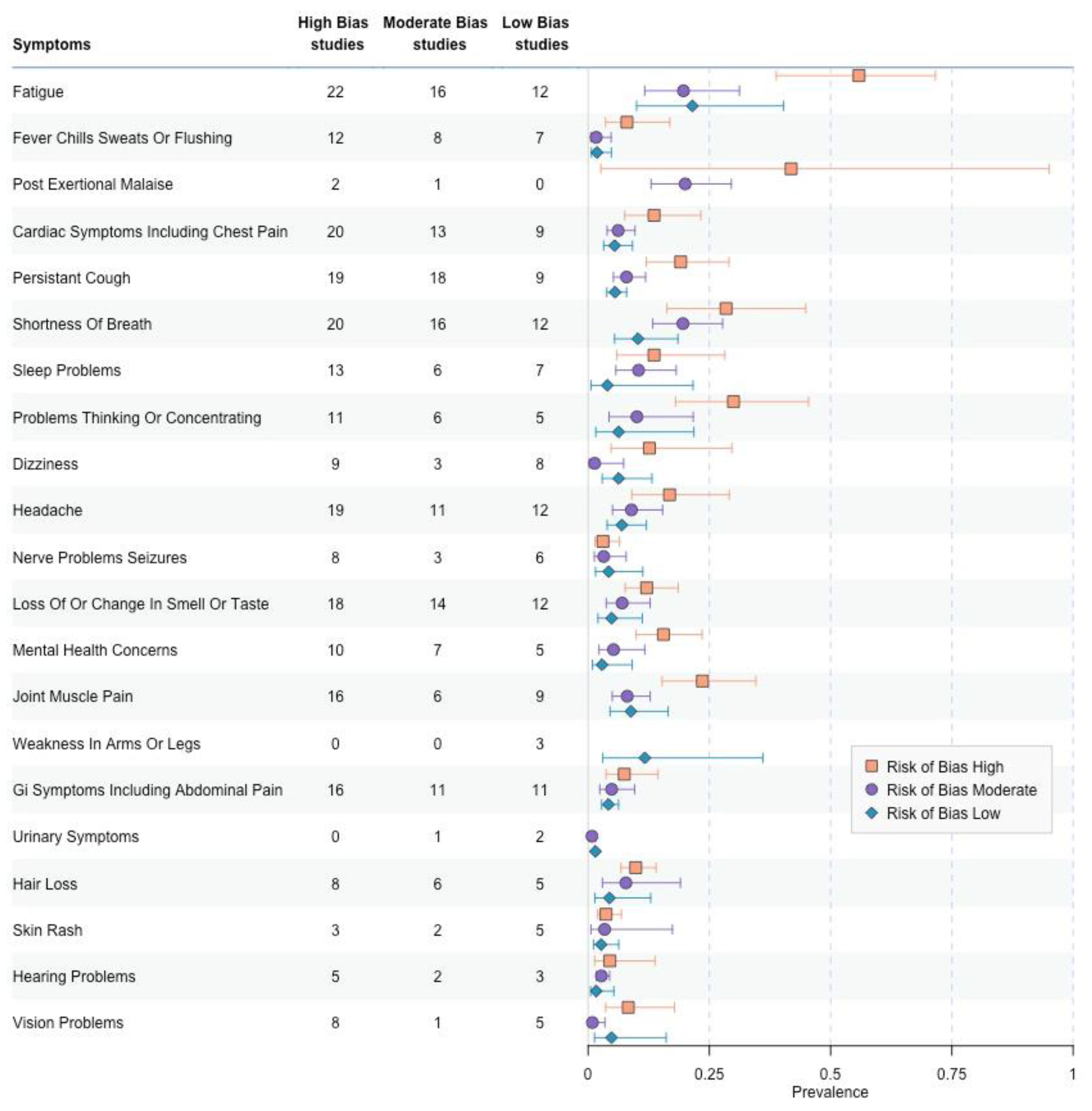

3.6. Risk of Bias Comparisons

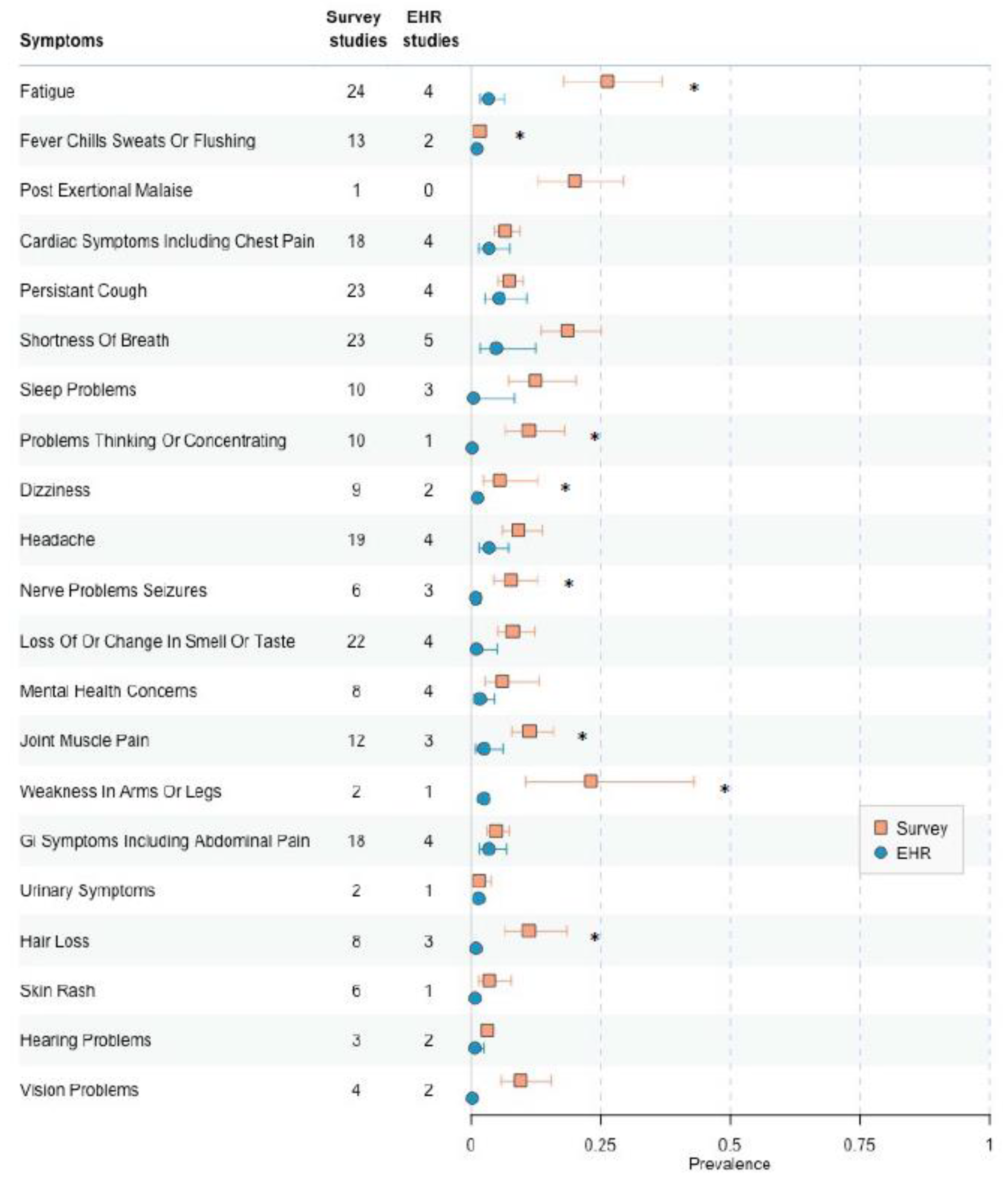

3.7. Low-to Moderate Risk fo Bias, EHR Versus Survey Collection

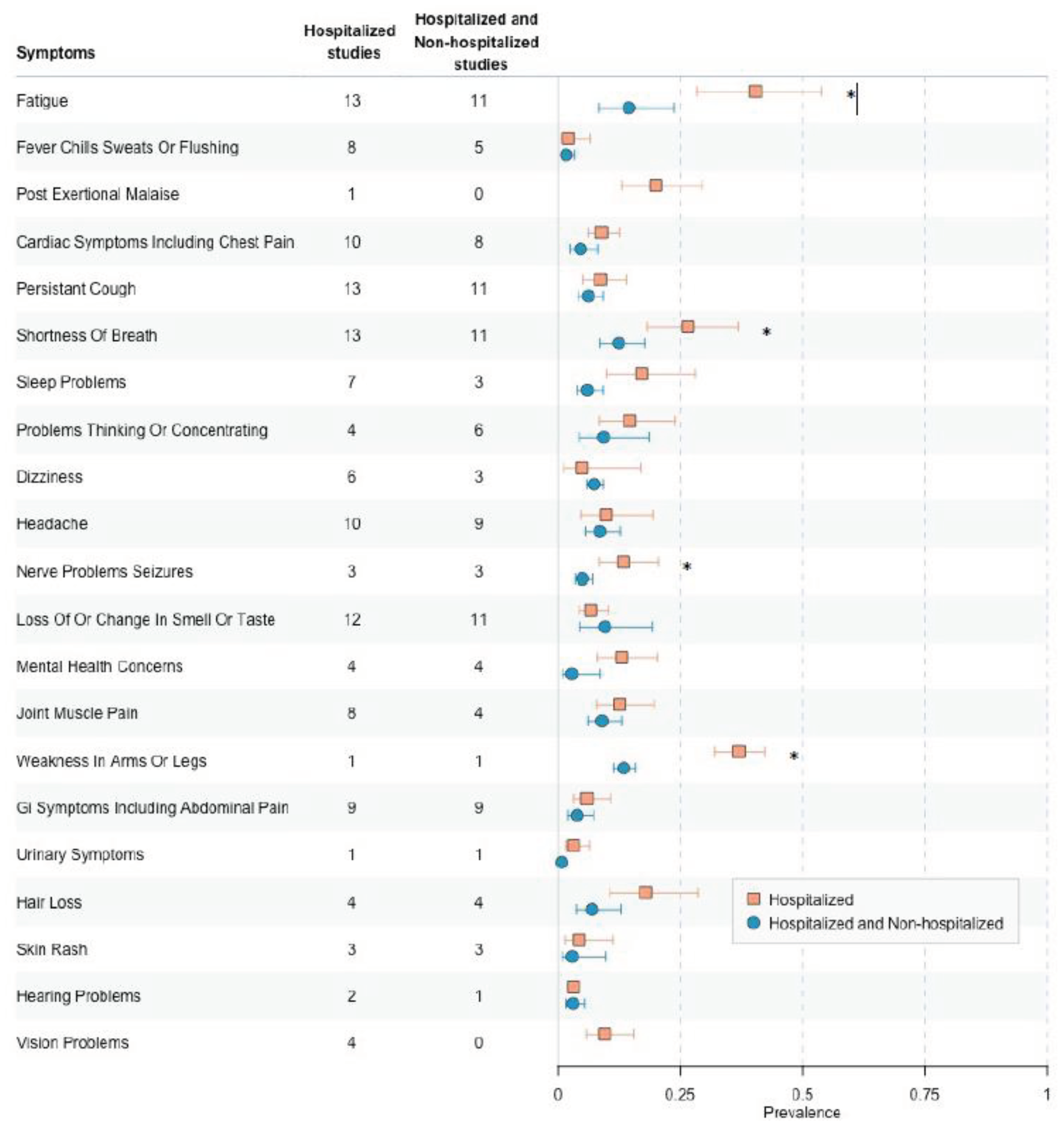

3.8. Low-to Moderate Risk of Bias, Hospitalized Versus Hospitalized and Non-Hospitalized among Survey Studies

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Michelen M, Manoharan L, Elkheir N, et al. Characterising long COVID: a living systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6(9). [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 2021;27(4):601-615. [CrossRef]

- Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ 2021;374:n1648. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ 2020;370:m3026. [CrossRef]

- OWID. Our World in Data. (ourworldindata.org).

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023;21(3):133-146. [CrossRef]

- Merad M, Blish CA, Sallusto F, Iwasaki A. The immunology and immunopathology of COVID-19. Science 2022;375(6585):1122-1127. [CrossRef]

- Thaweethai T, Jolley SE, Karlson EW, et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA 2023;329(22):1934-1946. [CrossRef]

- CTEP. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events NIH National Cancer Institute, DCTD Division of ZCancer Treatment & Diagnosis 2021 (https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_60).

- Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65(9):934-9. [CrossRef]

- Borenstein M, Higgins JP. Meta-analysis and subgroups. Prev Sci 2013;14(2):134-43. [CrossRef]

- Larsen NW, Stiles LE, Shaik R, et al. Characterization of autonomic symptom burden in long COVID: A global survey of 2,314 adults. Front Neurol 2022;13:1012668. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- 13. FAIR H. A detail study of patients with long-haul COVID: An analysis of Private Healthcare Claims. A FAIR Health White Paper: 2021.

- Goërtz YMJ, Van Herck M, Delbressine JM, et al. Persistent symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: the post-COVID-19 syndrome? ERJ Open Res 2020;6(4) (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Xu H, Jiang H, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of discharged coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a prospective cohort study. QJM 2020;113(9):657-665. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Bliddal S, Banasik K, Pedersen OB, et al. Acute and persistent symptoms in non-hospitalized PCR-confirmed COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 2021;11(1):13153. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Blomberg B, Mohn KG, Brokstad KA, et al. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat Med 2021;27(9):1607-1613. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Buttery S, Philip KEJ, Williams P, et al. Patient symptoms and experience following COVID-19: results from a UK-wide survey. BMJ Open Respir Res 2021;8(1) (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Horberg MA, Watson E, Bhatia M, et al. Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 with clinical condition definitions and comparison in a matched cohort. Nat Commun 2022;13(1):5822. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Pinto MD, Borelli JL, et al. COVID Symptoms, Symptom Clusters, and Predictors for Becoming a Long-Hauler Looking for Clarity in the Haze of the Pandemic. Clin Nurs Res 2022;31(8):1390-1398. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- LaVergne SM, Stromberg S, Baxter BA, et al. A longitudinal SARS-CoV-2 biorepository for COVID-19 survivors with and without post-acute sequelae. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21(1):677. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Naik S, Haldar SN, Soneja M, et al. Post COVID-19 sequelae: A prospective observational study from Northern India. Drug Discov Ther 2021;15(5):254-260. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- García-Abellán J, Padilla S, Fernández-González M, et al. Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 is Associated with Long-term Clinical Outcome in Patients with COVID-19: a Longitudinal Study. J Clin Immunol 2021;41(7):1490-1501. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Horwitz LI, Garry K, Prete AM, et al. Six-Month Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized with Severe COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med 2021;36(12):3772-3777. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Darcis G, Bouquegneau A, Maes N, et al. Long-term clinical follow-up of patients suffering from moderate-to-severe COVID-19 infection: a monocentric prospective observational cohort study. Int J Infect Dis 2021;109:209-216. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Becker C, Beck K, Zumbrunn S, et al. Long COVID 1 year after hospitalisation for COVID-19: a prospective bicentric cohort study. Swiss Med Wkly 2021;151:w30091. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med 2021;27(4):626-631. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Danesh V, Arroliga AC, Bourgeois JA, et al. Symptom Clusters Seen in Adult COVID-19 Recovery Clinic Care Seekers. J Gen Intern Med 2023;38(2):442-449. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021;38:101019. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi B, Sudry T, Flaks-Manov N, et al. Long covid outcomes at one year after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2023;380:e072529. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Roessler M, Tesch F, Batram M, et al. Post-COVID-19-associated morbidity in children, adolescents, and adults: A matched cohort study including more than 157,000 individuals with COVID-19 in Germany. PLoS Med 2022;19(11):e1004122. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 2021;174(4):576-578. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Frontera JA, Lewis A, Melmed K, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Prolonged Cognitive and Psychological Symptoms Following COVID-19 in the United States. Front Aging Neurosci 2021;13:690383. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Cirulli E, KM SB, Riffle S, et al. Long-term COVID_19 symptoms in large unselected population. BMJ Yale [Preprint]2020.

- Wanga V, Chevinsky JR, Dimitrov LV, et al. Long-Term Symptoms Among Adults Tested for SARS-CoV-2 - United States, January 2020-April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70(36):1235-1241. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Tabacof L, Tosto-Mancuso J, Wood J, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 Syndrome Negatively Impacts Physical Function, Cognitive Function, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Participation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2022;101(1):48-52. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Reese JT, Blau H, Casiraghi E, et al. Generalisable long COVID subtypes: findings from the NIH N3C and RECOVER programmes. EBioMedicine 2023;87:104413. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2021;397(10270):220-232. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Kuodi P, Gorelik Y, Zayyad H, et al. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and reported incidence of post-COVID-19 symptoms: cross-sectional study 2020-21, Israel. NPJ Vaccines 2022;7(1):101. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y, et al. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect 2020;81(6):e4-e6. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: A cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol 2021;93(2):1013-1022. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Daher A, Balfanz P, Cornelissen C, et al. Follow up of patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease sequelae. Respir Med 2020;174:106197. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Milne A, et al. Patient outcomes after hospitalisation with COVID-19 and implications for follow-up: results from a prospective UK cohort. Thorax 2021;76(4):399-401. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Bellan M, Soddu D, Balbo PE, et al. Respiratory and Psychophysical Sequelae Among Patients With COVID-19 Four Months After Hospital Discharge. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(1):e2036142. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, Group GAC-P-ACS. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324(6):603-605. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Liang L, Yang B, Jiang N, et al. Three-month Follow-up Study of Survivors of Coronavirus Disease 2019 after Discharge. J Korean Med Sci 2020;35(47):e418. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez O, Merino E, Leon-Ramirez JM, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Incidence and risk factors: A Mediterranean cohort study. J Infect 2021;82(3):378-383. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Morin L, Savale L, Pham T, et al. Four-Month Clinical Status of a Cohort of Patients After Hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA 2021;325(15):1525-1534. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Zhao YM, Shang YM, Song WB, et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine 2020;25:100463. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Munblit D, Bobkova P, Spiridonova E, et al. Incidence and risk factors for persistent symptoms in adults previously hospitalized for COVID-19. Clin Exp Allergy 2021;51(9):1107-1120. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Sarrafzadegan N, Mohammadifard N, Javanmard SH, et al. Isfahan COVID cohort study: Rationale, methodology, and initial results. J Res Med Sci 2022;27:65. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Petersen MS, Kristiansen MF, Hanusson KD, et al. Long COVID in the Faroe Islands: A Longitudinal Study Among Nonhospitalized Patients. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73(11):e4058-e4063. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Xiong Q, Xu M, Li J, et al. Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: a single-centre longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021;27(1):89-95. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Dryden M, Mudara C, Vika C, et al. Post-COVID-19 condition 3 months after hospitalisation with SARS-CoV-2 in South Africa: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2022;10(9):e1247-e1256. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Kayaaslan B, Eser F, Kalem AK, et al. Post-COVID syndrome: A single-center questionnaire study on 1007 participants recovered from COVID-19. J Med Virol 2021;93(12):6566-6574. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Peghin M, Palese A, Venturini M, et al. Post-COVID-19 symptoms 6 months after acute infection among hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021;27(10):1507-1513. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Venturelli S, Benatti SV, Casati M, et al. Surviving COVID-19 in Bergamo province: a post-acute outpatient re-evaluation. Epidemiol Infect 2021;149:e32. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Anastasio F, Barbuto S, Scarnecchia E, et al. Medium-term impact of COVID-19 on pulmonary function, functional capacity and quality of life. Eur Respir J 2021;58(3) (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Sigfrid L, Drake TM, Pauley E, et al. Long Covid in adults discharged from UK hospitals after Covid-19: A prospective, multicentre cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2021;8:100186. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Søraas A, Kalleberg KT, Dahl JA, et al. Persisting symptoms three to eight months after non-hospitalized COVID-19, a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2021;16(8):e0256142. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Heesakkers H, van der Hoeven JG, Corsten S, et al. Clinical Outcomes Among Patients With 1-Year Survival Following Intensive Care Unit Treatment for COVID-19. JAMA 2022;327(6):559-565. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Tleyjeh IM, Saddik B, AlSwaidan N, et al. Prevalence and predictors of Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome (PACS) after hospital discharge: A cohort study with 4 months median follow-up. PLoS One 2021;16(12):e0260568. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Mandal S, Barnett J, Brill SE, et al. ‘Long-COVID’: a cross-sectional study of persisting symptoms, biomarker and imaging abnormalities following hospitalisation for COVID-19. Thorax 2021;76(4):396-398. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Robles M, Iguaran-Bermúdez MDR, García-Klepizg JL, Lorenzo-Villalba N, Méndez-Bailón M. Ninety days post-hospitalization evaluation of residual COVID-19 symptoms through a phone call check list. Pan Afr Med J 2020;37:289. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Jacobson KB, Rao M, Bonilla H, et al. Patients With Uncomplicated Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Have Long-Term Persistent Symptoms and Functional Impairment Similar to Patients with Severe COVID-19: A Cautionary Tale During a Global Pandemic. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73(3):e826-e829. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Elkan M, Dvir A, Zaidenstein R, et al. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures After Hospitalization During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey Among COVID-19 and Non-COVID-19 Patients. Int J Gen Med 2021;14:4829-4836. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Baruch J, Zahra C, Cardona T, Melillo T. National long COVID impact and risk factors. Public Health 2022;213:177-180. (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Barman MP, Rahman T, Bora K, Borgohain C. COVID-19 pandemic and its recovery time of patients in India: A pilot study. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020;14(5):1205-1211. [CrossRef]

- Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, et al. Short-term and Long-term Rates of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(10):e2128568. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).