Submitted:

21 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- tissue biopsy cannot be performed in certain anatomical sites, which interferes with timely diagnosis/prognosis of many forms of solid tumors, particularly in pediatric patients. Acquiring samples by an invasive method throughout treatment to monitor tumor progress, response to therapy, and relapse pose a major challenge to tumor profiling [8]. Such challenge manifests more clearly in molecular profiling of pediatric solid tumors. For instance, malignant primary brain tumors are the most common cancers in children under the age of 14 years [9]. These forms of cancer are not only difficult to diagnose but also difficult to monitor their response to therapy. Such difficulties are directly linked to tissue biopsy, which is not suitable for repetitive sampling and cannot be performed in certain anatomical locations [10]. Biopsies through surgery have further limitations in terms of time, cost of repeatability and age of patient [11].

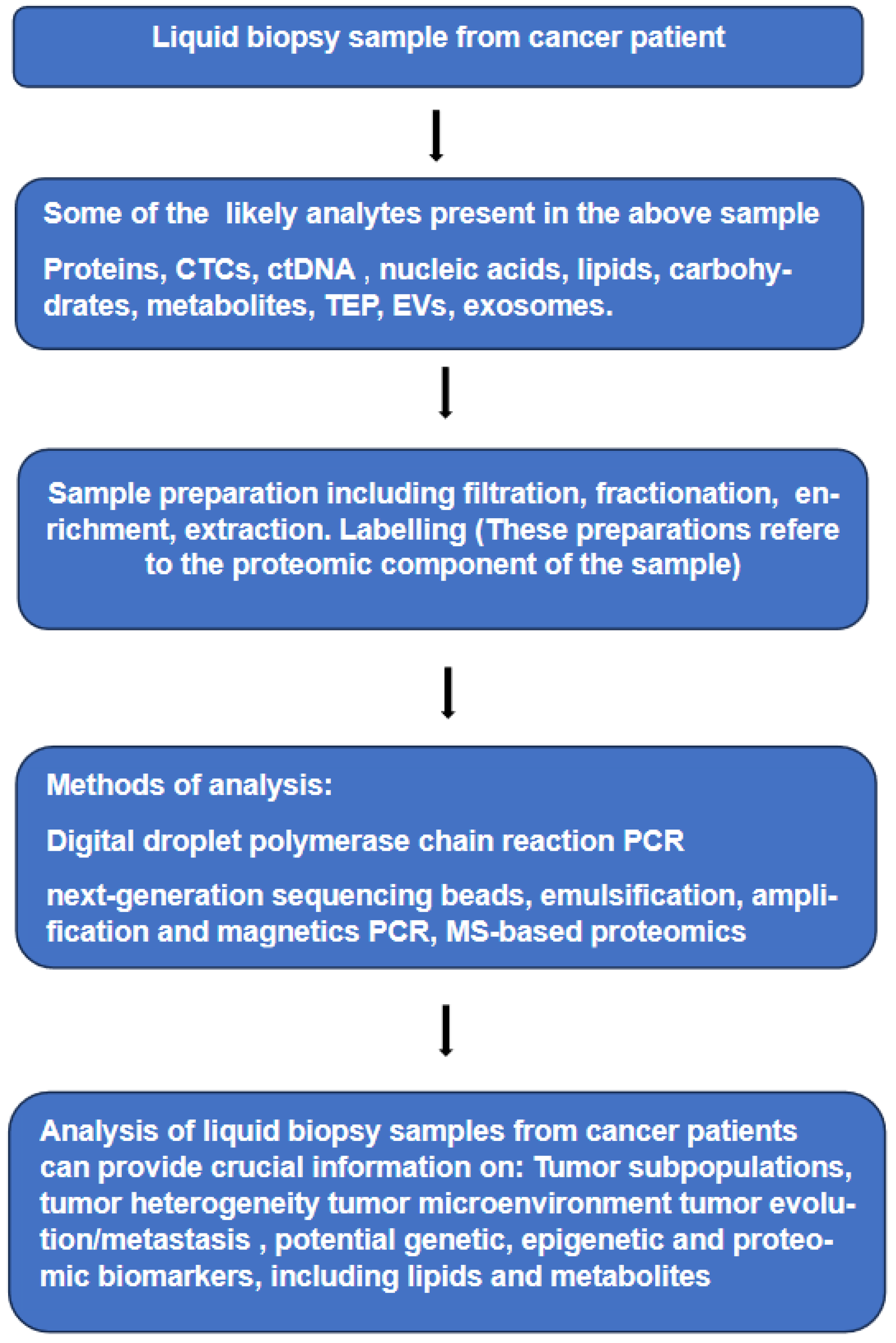

- Molecular characterization obtained by tissue biopsy is intrinsically partial and often not informative due to low quantity and/or poor-quality of tumor DNA. On the other hand, tumor cells from primary and metastatic sites, which are shed into various body fluids at sufficient concentration can offer. the chance to analyze samples containing tumor genetic and proteomic materials (see Figure 1). Furthermore, repetitive sampling through liquid biopsies has the potential to track the evolutionary dynamics and heterogeneity of tumors and may indicate very early emergence of resistance to therapy, residual disease and recurrence. It can be said that the evolution of targeted therapy emphasized the need for longitudinal monitoring of molecular changes within tumors to help guiding the therapeutic regimes. In addition, non-invasive, longitudinal assessment of tumors is necessary for confident tracking of potential biomarkers shed into various body fluids of patients [12,13].

- It is becoming evident that liquid biopsies capture part of the tumor shed into a body fluid. Analyses of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA obtained in a minimally invasive method may furnish molecular information highly relevant to the characterization of the parent tumor of these circulating components. Initial application of liquid biopsies in clinical oncology were limited to the investigation of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). Further development of the method extended such investigations to other molecular entities, which can be divided into two groups, the first includes both large and small molecules without cells and/or without a subcellular structure in the body fluid; these include proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, carbohydrates and metabolites.

2. Discussion

2.1. Is Liquid Biopsy an Alternative or Complementary to Tissue Biopsy?

2.2. Liquid Biopsy in Pediatric Tumors

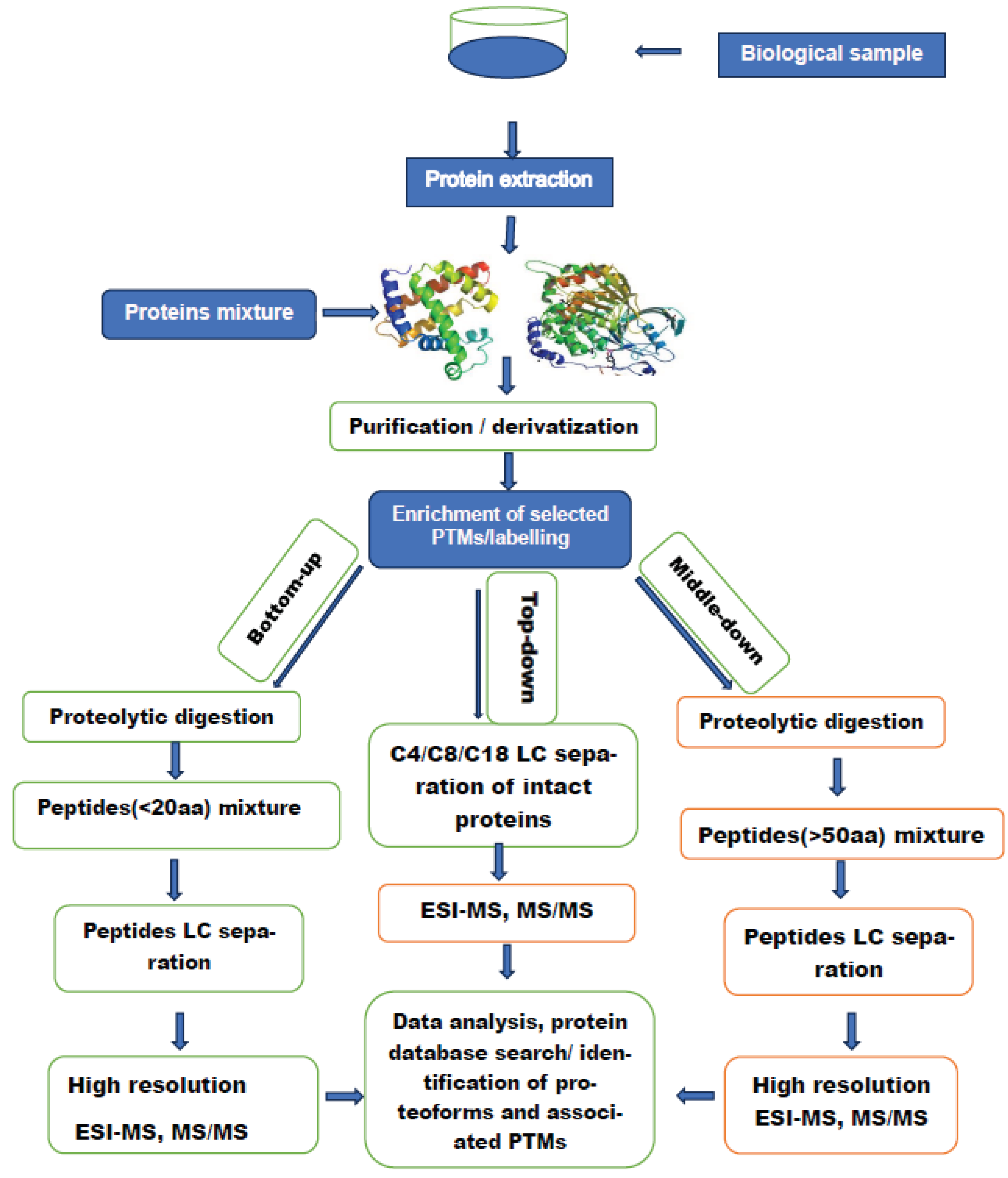

2.3. Proteomic Analysis of Circulating Proteins in Pediatric Liquid Biopsies

2.3.1. Post-Translational Modifications as Disease Biomarkers

2.3.2. Investigation of Histone Post Translational Modifications

General Remarks

- 4.

- Both research scientists and treating oncologists are in agreement that liquid biopsies (LBs) could be a valid alternative to surgical biopsies as a method for molecular profiling of various forms of cancer. This agreement is based on a number of advantages offered by this emerging method. Which are missing in tissue biopsy. First, noninvasive repetitive sampling throughout the course of the disease, such characteristic is essential to have continuous update on the evolution of the tumor, which gives a robust indication on response to therapy and early warning of emerging drugs resistance. Analysis of genetic and proteomic material circulating in liquid biopsy samples furnish detailed information on the heterogeneity of tumor, which are necessary for correct patient stratification and the choice of therapy. It is interesting to note that Intratumor heterogeneity revealed by multiregion sequencing implies that analysis based on tissue biopsy samples can lead to underestimation of the tumor genomics landscape, which may present major challenges to personalized-medicine and biomarkers development [98] Other advantages of liquid biopsies have been mentioned earlier in the text.

- 5.

- Existing literature suggests that pediatric neuro-oncology is one area, which is likely to benefit most from the increasing use of (LBs) in the molecular analysis of tumors. Due to the high risk associated with tissue biopsy, diagnosis and understanding of pediatric brain tumors have lagged behind other forms of cancer. The shift from surgical biopsies to (LBs) allowed access to certain anatomical zones, which could not be accessed by surgery., and second, serial sampling and major information on the heterogeneity of the disease allow more accurate patient stratification and almost real time monitoring of the evolution of the tumor. Both elements are essential on the path leading to more successful personalized therapy. The application of (LBs) for molecular diagnosis and treatment response in pediatric brain tumors has been demonstrated in four recent studies [99,100,101,102].

- 6.

- We asked in this text whether (LB) is an alternative to tissue biopsy.? Currently, it is immature to talk about complete displacement of tissue biopsy in favor of liquid biopsy. This observation can be supported by the following considerations. Tissue biopsy is not only a sampling method but also a method of cure for the majority of localized cancers without the need for systematic therapy [103]. At the present time, most genetic and proteomic assays designed to characterize circulating entities in (LBs) are not sensitive enough to allow a complete shift from tissue biopsy. In other words, such transition is dependent on the extent of progress in oncology research with all its components to put in place standardized assays of high sensitivity, high specificity, reproducible and easy to transfer and implement in clinical settings The authors believe that the complexity and the vast diversity of tumors will ensure that both methods of sampling will continue to serve oncology research for years to come.

- 7.

- Various works cited in this text suggests that many (LBs) with a focus on early detection [104] of various forms of cancer lack the sensitivity for a reliable detection of early-stage cancers This observation applies to both genetic and proteomic cancer biomarkers. So far information in hand suggest that tumor derived genetic biomarkers are not always shed into the blood stream in early stages, and even when they are shed into the bloodstream, they exist at very low concentrations [105,106]. Similar observations can be made regarding cancer protein biomarkers. For example, prostate specific antigen (PSA) and carcinoma antigen-125 (CA-125) are often not elevated in cancer patients, even in those with advanced stage of the disease [4]. Furthermore, both markers lack specificity as they can be elevated in cancer-free patients [107].

- 8.

- Many forms of cancer can be completely cured if they are detected in their very early stages, Successful cure can be also enhanced if these cancers can be predicted through reliable identification of predictive biomarkers. Most of these potential biomarkers are found in liquid biopsies of both healthy controls and patients. Currently, many predictive biomarkers for various forms of cancer are based on the investigation of genomic material obtained by both liquid and tissue biopsies. Biomarkers based on the proteomic analyses of the same media are still lagging behind their genomic counterparts. The gap between the two approaches has different reasons, including the complexity of the proteome compared to the genome and the extremely wide dynamic range of the investigated proteins. Despite notable progress in proteomic research, the area of validated predictive biomarkers transferable to clinical oncology remains poorly served, there is a prevailing opinion that to enhance the role of the proteomic analyses of body fluids in the search for predictive biomarkers , assays more sensitive , more specific reproducible and easy to transfer to clinical practice are necessary, More rigorous selection and validation of potential disease biomarkers and their efficient transfer to clinical practice. A successful transfer requires rigorous. standardization of the working practices regarding all aspects of (LBS) analyses

- 9.

- Molecular diagnostics based on tumor’s genomic analysis, including those based on (LBs) reveals a complex and highly challenging task for treating oncologists and researchers alike. The evolving list of diagnostic, prognostic and predictive biomarkers in some way interferes with a reliable tracking of the link between actionable genomic alterations and targeted therapies in clinical trials. Most recent literature reports dozens to hundreds of genes, which have to be considered in the process of choosing a given therapy. One of the initiatives to help treating oncologists in decision making has been recently reported [108] The Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Al Nahyan Institute for Personalized Cancer Therapy (IPCT) at MD Anderson Cancer Center has developed a knowledge base, available at https://personalizedcancertherapy.org or https://pct.mdanderson.org (PCT). This knowledge base provides information on the function of common genomic alterations and their therapeutic implications.

Conclusions

Abbreviations

| LB | Liquid biopsy. |

| CTCs | Circulating tumor cells. |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA. |

| CAF | Cancer-related fibroblasts |

| TEP | Tumor-educated platelets |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| DdPCR | Digital droplet polymerase chain reaction |

| BEAMing PCR | Beads, emulsification, amplification and magnetics PCR |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| LC/MS | Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry |

| MS/MS | Tandem mass spectrometry |

| IM | Ion mobility |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| PTMs | post-translational modifications |

| CID | Collision induced dissociation |

| ET | Electron transfer |

| EC | Electron capture |

| UVPD | Ultra Violet photodissociation |

| WB | Western blotting |

| RPPA | Reverse-phase protein array |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ESI | Electrospray ionization |

| SELDI | Surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization |

| TOF-MS | Time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| RPLC | Reversed-phase liquid chromatography |

| PSA | Prostate specific antigen (PSA) |

| CA-125 | Carcinoma antigen-125 (CA-125) |

References

- Pantel, K.; Alix-Panabières, C. Circulating tumor cells in cancer patients: Challenges and perspectives. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2010, 16, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alix-Panabieres,C; Pantel, K. Challenges in circulating tumour cell research. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14, 623–631. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantel, K.; Speicher, M.R. The biology of circulating tumor cells. Oncogene 2016, 35, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettegowda, C.; et al. Detection of Circulating Tumor DNA in Early- and Late-Stage Human Malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014, 6, 224ra24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adkins, J.N.; Varnum, S.M.; Auberry, K.J.; Moore, R.J.; Angell, N.H.; Smith, R.D. : Springer, D.L.; Pounds, J.G. Toward a human blood serum proteome: Analysis by multidimensional separation coupled with mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2002, 12, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Russell, T.; Wood, G.; Desiderio, D.M. Analysis of the human lumbar cerebrospinal fluid proteome. Electrophoresis 2002, 23, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazares, L.H.; Adam, B.L.; Ward, M.D.; Nasim, S.; Schellhammer, P.F.; Semmes, O.J.; et al. Normal, benign, preneoplastic, and malignant prostate cells have distinct protein expression profiles resolved by surface enhanced laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Clin Cancer Res 2002, 8, 2541–2552. [Google Scholar]

- Perakis, S.; Speicher, M.R. Emerging concepts in liquid biopsies. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Truitt, G.; Boscia, A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 20, iv1–iv86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Gittleman, H.; Patil, N.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, v1–v100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Hurley, J.; Roberts, D.; Chakrabortty, S.K.; Enderle, D.; Noerholm, M.; Breakefield, X.O.; Skog, J.K. Exosome-Based Liquid Biopsies in Cancer: Opportunities and Challenges. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bounajem, M.T.; Karsy, M.; Jensen, R.L. Liquid biopsies for the diagnosis and surveillance of primary pediatric central nervous system tumors: A review for practicing neurosurgeons. Neurosurg. Focus 2020, 48, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, T.D.; Jin, M.C.; Bernhardt, L.J.; Bettegowda, C. Liquid biopsy for pediatric diffuse midline glioma: A review of circulating tumor DNA and cerebrospinal fluid tumor DNA. Neurosurg. Focus 2020, 48, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In ‘t Veld, S.G.J.G.; Wurdinger, T. Tumor-Educated Platelets. Blood 2019, 133, 2359–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, A; Lim, A.R.; Ghajar, C.M. Circulating and Disseminated Tumor Cells: Harbingers or Initiators of Metastasis? Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 40–61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alix-Panabières, C. EPISPOT assay: Detection of viable DTCs/CTCs in solid tumor patients. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2012, 195, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Di Meo, A.; Bartlett, J.; Cheng, Y.; Pasic, M.D.; Yousef, G. M. Liquid biopsy: A step forward towards precision medicine in urologic malignancies 16:80. Molecular Cancer 2017, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conteduca, V.; Wetterskog, D.; Sharabiani, M. T. et al. Androgen receptor gene status in plasma DNA associates with worse outcome on enzalutamide or abiraterone for castration-resistant prostate cancer: A multi-institution correlative biomarker study. Ann Oncol. 2017, 28, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindson, C. M.; et al. Absolute quantification by droplet digital PCR versus analog real-time PCR. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 1003–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, J. A.; Guillerm, E.; Coulet, F.; Larsen, A. K.; Lacorte, J. M. The role of BEAMing and digital PCR for multiplexed analysis in molecular oncology in the era of next-generation sequencing. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2017, 21, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos; N, Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz Jr, L.A.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558.

- Li, L.; Sun, C.; Sun, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wu, R.; et al. Tissue expansion. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aebersold, R.; Mann, M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature 2003, 422, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017, 67, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, M.; Rowan, A.J.; Horswell, S.; Larkin, J.; Endesfelder, D.; Gronroos, E.; Martinez, P.; Matthews, N.; Stewart, A.; Tarpey, P.; et al. Intratumor heterogeneityand branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012, 366, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D.; Javed, A.A.; Thoburn ,C.; Wong ,F.; Tie ,J.; Gibbs ,P.; Schmidt ,C.M.; Yip-Schneider, M.T.; et al. Combined circulating tumor DNA and protein biomarker-based liquid biopsy for the earlier detection of pancreatic cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017, 114, 10202–10207. [CrossRef]

- Cree, I.A.; Uttley, L,; Woods, H.B.; Kikuchi, H.; Reiman, A.; Harnan, S.; Whiteman, B.L.; Philips, S.T. et al. The evidence base for circulating tumour DNA blood-based biomarkers for the early detection of cancer: A systematic mapping review. BMC Cancer 2017, 1, 697.

- Bardelli, A.; Pantel, K. Liquid Biopsies, What We Do Not Know (Yet). Cancer Cell. 2017, 31, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Gittleman, H.; Patil, N.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, v1–v100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom Q., T.; Patil, N.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan J., S. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2013-2017. Neuro-Oncol. 2020, 22, iv1–iv96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; ; Gardner, S; Snuderl, M. The Role of Liquid Biopsies in Pediatric Brain Tumors. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2020, 79, 934–940. [CrossRef]

- Louis, D. N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, D.R; Petty, B.G.; Compton, C.; Cristofanilli, M.; Deisseroth, A.; Hayes, D.F.; Kapke, G.; Kumar, P.; Lee, J.S. Considerations in the development of circulating tumor cell technology for clinical use. J Trans Med. 2012, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla, C.; Soria, E.; Ramirez, N. The identification and isolation of CTCs: A biological Rubik’s cube. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018, 126, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.M. Liquid biopsy: Where did it come from, what is it, and where is it going? Investig Clin Urol. 2019, 60, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labelle, M.; Begum, S.; Hynes, R.O. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011, 20, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gal, K.; Ibrahim, M.X.; Wiel, C.; Sayin, V.I.; Akula, M.K.; Karlsson, C.; Dalin, M.G.; Akyürek, L.M.; Lindahl, P.; Nilsson, J. Antioxidants can increase melanoma metastasis in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2015, 7, 308re308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Edmonson, M.N.; Gawad, C.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Rusch, M.C.; Easton, J.; et al. Pan-cancer genome and transcriptome analyses of 1699 pediatric leukaemias and solid tumours. Nature 2018, 555, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruci, D.; Cho, W.C.S.; Nobili, V.; Locatelli, F.; Alisi, A. Drug Transporters and Multiple Drug Resistance in Pediatric Solid Tumors. Curr. Drug Metab. 2016, 17, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirumalai, R.S.; Chan, K.C.; Prieto, D.R.A.; Issaq, H.J.; Conrads, T.P.; Veenstra, T.D. Characterization of the low molecular weight human serum proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics 2003, 2, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, P.E.; Holdt, L.M.; Teupser, D.; Mann, M. Revisiting biomarker discovery by plasma proteomics. Mol Syst Biol. 2017, 13, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M. R.; Højrup, P.; Roepstorff, P. Characterization of Gel-separated Glycoproteins Using Two-step Proteolytic Digestion Combined with Sequential Microcolumns and Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2005, 4, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mysling, S.; Salbo, R.; Ploug, M.; Jørgensen, T. J. D. Electrochemical reduction of disulfide-containing proteins for hydrogen/deuterium exchange monitored by mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobst, C.E.; Kaltashov, I.A. Enhancing the quality of H/D Exchange measurements with mass spectrometry detection in disulfide-rich proteins using electron capture dissociation. Anal.Chem. 2014, 86, 5225–5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, J.R.; McCormack, A.L.; Schieltz, D.; Carmack, E.; Link, A. Direct analysis of protein mixtures by tandem mass spectrometry. J. Protein Chem. 1997, 16, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoli, S.; Lin, S.; Karch, K.R.; Garcia, B.A. Bottom-Up and Middle-Down Proteomics Have Comparable Accuracies in Defining Histone Post-Translational Modification Relative Abundance and Stoichiometry. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 3129–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, D.P.; Rawlins, C.M.; DeHart, C.J.; Fornelli, L.; Schachner, L.; Lin, Z.; Lippens, J.L.; Aluri, K.C.; Sarin, R.; Chen, B.; Lantz, C. et al. Best practices and benchmarks for intact protein analysis for top-down mass spectrometry. Nature Methods, 2019; 16, 587–594. [Google Scholar]

- Emmalyn, J.; Dupree, M.J.; Hannah, Y.; Marius, M.; Brindusa, A.P. et al. Critical Review of Bottom-Up Proteomics: The Good, the Bad, and the Future of This Field. Proteomes. 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Coradin, M.; Porter, E.G.; Garcia, B. : Accelerating the Field of Epigenetic Histone Modification Through Mass Spectrometry–Based. Mol Cell Proteomics 2021, 20, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zheng, S.; Han, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhai, G.; Bai, X.; He, X.; Fan, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K. Maleic anhydride labeling-based approach for quantitative proteomics and successive derivatization of peptides. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 8259–8265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, B. A.; Mollah, S.; Ueberheide, B. M.; Busby, S. A.; Muratore, T. L.; Shabanowitz, J.; Hunt, D. F. Chemical derivatization of histones for facilitated analysis by mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaf, A.; Byrne, K.H.; Chae, P.S. Chapter Four - Amphipathic Agents for Membrane Protein Study. Methods in Enzymology. 2015, 557, 57–94. [Google Scholar]

- Spreafico, F.; Bongarzone, I.; Pizzamiglio, S.; Magni, R.; et al. Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid from children with central nervous system tumors identifies candidate proteins relating to tumor metastatic spread. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 46177–46190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galogahi, F.M.; Zhu, Y.; Hongjie An, H.; Nguyen, N.T. Core-shell microparticles: Generation approaches and applications. Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices 2020, 5, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutzer, S.E.; Liu, T.; Natelson, B.H.; Angel, T.E.; Schepmoes, A.A.; Purvine, S.O.; Hixson, K.K.; Lipton, M.S.; Camp, D.G. II; Coyle, P.K.; Smith, R.D.; Bergquist, J. Establishing the Proteome of Normal Human Cerebrospinal Fluid. PLoS ONE. 2010, 5, e10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bont, J. M.; den Boer, M. L.; Reddingius, R.E.; et al. Identification of Apolipoprotein A-II in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Pediatric Brain Tumor Patients by Protein Expression Profiling Clinical Chemistry 2006, 52, 1501–1509.

- Hutchens, T.W.; Yip, T.T. New desorption strategies for the mass spectrometric analysis of macromolecules. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1993, 7, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, I. H. G. S. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome Nature 2004, 431, 931–945. 431.

- Gaudet, P.; Michel, P.-A.; Zahn-Zabal, M.; Britan, A.; Cusin, I.; et al. The neXtProt knowledgebase on human proteins: 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D177–D182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, A.; Kampf, C.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt, C. Uniport: A hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D204–D212. [Google Scholar]

- Mnatsakanyan, R.; Shema ,G.; Basik ,M.; Batist ,G.; Borchers ,C.H.: Sickmann ,A.; Zahedi, R.P. Detecting post-translational modification signatures as potential biomarkers in clinical mass spectrometry. Expert Rev Proteomics 2018, 15, 515–535. [CrossRef]

- Hornbeck, P.V.; Zhang, B.; Murray, B.; et al. Phospho-Site Plus: Mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D512–D520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.P.; Giles, K.; Bateman, R.H.; Radford, S.E.; Ashcroft, A.E. Monitoring Copopulated Conformational States During Protein Folding Events Using Electrospray Ionization-Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 18, 2180–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubarev, R. A.; Horn, D. M.; Fridriksson, E. K.; Kelleher, N. L.; Kruger, N. A.; Lewis, M. A.; Carpenter, B. K.; McLafferty, F. W. Electron capture dissociation for structural characterization of multiply charged protein cations. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syka, J.E.; Coon, J.J.; Schroeder, M.J.; Shabanowitz, J.; Hunt, D.F. Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 9528–9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodin, R. L.; Bomse, D. S.; Beauchamp, J. L. Multiphoton dissociation of molecules with low power continuous wave infrared laser radiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 3248–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, W. D.; Delbert, S. S.; Hunter, R. L.; Mc Iver, R. T. Fragmentation of oligopeptide ions using ultraviolet-laser radiation and fourier-transform mass-spectrometry. J Am Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 7288–7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, D. F.; Shabanowitz, J.; Yates, J. R. Peptide sequence- analysis by laser photodissociation fourier-transform mass spectrometry. J.Chem.Soc.Chem.Comm. 1987, 548–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Ackerveken, P.; Lobbens, A.; Turatsinze, J.-V.; Solis-Mezarino, V.; Völker-Albert, M.; Imhof, A.; Herzog, M. A novel proteomics approach to epigenetic profiling of circulating nucleosomes. Nature, Scientific Reports. 2021, 11, 7256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Ren, J.M.; Jia, X.; Levy, T.; Rikova, K.; Yang, V.; Lee, K.A.; Stokes, M.P.; Silva, J.C. Quantitative Profiling of Post-translational Modifications by Immunoaffinity Enrichment and LC-MS/MS in Cancer Serum without Immunodepletion. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2016, 15, 692–702. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, L.M.P.; Gonzales-Cope, M.; Zee, B.M.; Garcia, B.A. Breaking the histone code with quantitative mass spectrometry. Expert Review of Proteomics. 2011; 8, 631–643. [Google Scholar]

- Torrente ,M. P.; Zee, B.M.; Young, N.L.; Baliban,R.C.; LeRoy,G.; Christodoulos, A.F.; Hake,S.B. ; Garcia, B.A. Proteomic interrogation of human chromatin. PLoS ONE. 2011, 6, e24747. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart, S.B.; Dickson, B.M.; Raab, J.R.; Grzybowski, A.T.; Krajewski, K.; Guo, A.H; Strahl, B. D. An Interactive Database for the Assessment of Histone Antibody Specificity. Molecolar Cell. 2015, 59, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzarides, T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007, 128, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casci, T. Chip on chips. Nat Rev Genet , 2001, 2, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, M.F.; Esteban Ballestar, E.; Villar-Garea, A.; Boix-Chornet, M.; et al. Loss of acetylation at Lys16 and trimethylation at Lys20 of histone H4 is a common hallmark of human cancer. Nat. Gen. 2005, 37, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, S.E.; Green, A.R.; Rakha, E.A.; Powe, D.G.; Ahmed, R.A.; Collins, H.M.; et al. Global histone modifications in breast cancer correlate with tumor phenotypes, prognostic factors, and patient outcome. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 3802–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauden, M.; Pamart, D.; Ansari, D.; Herzog, M.; Eccleston, M.; Micallef, J.; et al. Circulating nucleosomes as epigenetic biomarkers in pancreatic cancer. Clin Epigenet. 2015, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen H, Laird PW. Interplay between the cancer genome and epigenome. Cell. 2013, 153, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W. K. M.; Pugh, B. F. Understanding nucleosome dynamics and their links to gene expression and DNA replication. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, G.A.; Baliban, R.C.; Floudas, C.A. Proteome-wide post-translational modification statistics: Frequency analysis and curation of the Swissport database. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-Y.; Lee, T.-Y.; Kao, H.-J. et al. dbPTM in exploring disease association and cross-talk of post-translational modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D298–D308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, S. S.; Denu, J. M. Dynamic interplay between histone H3 modifications and protein interpreters: Emerging evidence for a "histone language". Chem Bio Chem 2011, 12, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, G.; Dimaggio, P. A.; Chan, E. Y.; Zee, B. M.; Blanco, M. A.; Bryant, B.; Flaniken, I. Z.; Liu, S.; Kang, Y.; Trojer, P.; Garcia, B. A. A quantitative atlas of histone modification signatures from human cancer cells. Epigenetics & Chromatin 2013, 6, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Millán-Zambrano, G.; Burton, A.; Bannister, A.J.; Schneider, R. Histone post-translational modifications cause and consequence of genome function Nature reviews Genetics Reviews. 2022; 23, 563. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Levitus, M.; Bustamante, C.; Widom, J. Rapid spontaneous accessibility of nucleosomal DNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, M. S.; Boeke, J. D.; Wolberger, C. Regulated nucleosome mobility and the histone code. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004, 11, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristobal, A.; Marino, F.; Post, H.; Van Den Toorn, H.W.P.; Mohammed, S.; Heck, A.J.R.; et al. Streptomyces erythraeus trypsin for proteomics applications. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 8, 1810–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhang, K.; Tian, S.; Fan, E.; Chen, L.; He, X.; Zhang, Y. Quantitative characterization of histone post-translational modifications using a stable isotope dimethyl labeling strategy. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 3779–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zheng, S.; Han, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhai, G.; Bai, X.; He, X.; Fan, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K. Maleic anhydride labeling-based approach for quantitative proteomics and successive derivatization of peptides. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 8259–8265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Fornelli, L.; Compton, P. D.; Sharma, S.; Canterbury, J.; Mullen, C.; Zabrouskov, V.; Fellers, R. T.; Thomas, P. M.; Licht, J. D. Unabridged analysis of human histone H3 by differential top-down mass spectrometry reveals hypermethylated proteoforms from MMSET/NSD2 overexpression. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2016, 15, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoli, S.; Garcia, B. A. Middle-down proteomics: A still unexploited resource for chromatin biology. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2017, 14, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.; Daujat, S.; Schneider, R. Lateral thinking: How histone modifications regulate gene expression. Trends Genet. 2016, 32, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, M.F.; Ballesta, E.; Villar-Garea, A.; Boix-Chornet, M.; Espada, J.; Schotta, G.; et al. Loss of acetylation at Lys16 and trimethylation at Lys20 of histone H4 is a common hallmark of human cancer. Nat Genet. 2005, 37, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenne, S. S.; Madsen, P. H.; Pedersen, I.S; Hveem, K.; Skorpen, F.; Krarup, H. B.; Giskeødegård, G.F. Colorectal cancer detected by liquid biopsy 2 years prior to clinical diagnosis in the HUNT study. Journal of Cancer 2023, 129, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumpton, B.M.; Graham, S.; Ida Surakka, I.; Skogholt, A.H.; Løset, M.; . Fritsche, L.G.; et al. The HUNT study: A population-based cohort for genetic research. Cell Genom. 2022, 2, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, M.; Rowan, A.J.; Horswell, S.M.; Larkin, J.; Endesfelder, D.; Gronroos, E.; Martinez, P.; Matthews, N.; et al. Intratumor Heterogeneity and Branched Evolution Revealed by Multiregion Sequencing. N Engl J Med 2012, 366, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A. P. Y.; Smith, K. S.; Kumar, R.; Paul, L.; Bihannic, L.; Lin, T.; et al. Serial assessment of measurable residual disease in medulloblastoma liquid biopsies. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 1519–1530.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, E.; Wierzbicki, K.; Tarapore, R. S.; Ravi, K.; Thomas, C.; Cartaxo, R.; et al. Serial H3K27M cell-free tumor DNA (cf-tDNA) tracking predicts ONC201 treatment response and progression in diffuse midline glioma. Neuro-Oncol. 2022, 24, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A. M.; Szalontay, L.; Bouvier, N.; Hill, K.; Ahmad, H.; Rafailov, J.; et al. Next-generation sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid for clinical molecular diagnostics in pediatric, adolescent and young adult brain tumor patients. Neuro-Oncol 2022, 24, 1763–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pages, M.; Uro-Coste, E.; Colin, C.; Meyronet, D.; Gauchotte, G.; Maurage, C.-A.; et al. The implementation of DNA methylation profiling into a multistep diagnostic process in pediatric neuropathology: A 2-year real-world experience by the French neuropathology network. Cancers. 2021, 13, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.A.; Richards, D; Cohn, A; Tummala, M; Lapham, R; Cosgrove, D.; et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann Oncol. 2021, 32, 1167–1177. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.M.; Liu, J.B.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, G.R.; et al. Power and promise of next-generation sequencing in liquid biopsies and cancer control. Cancer Control. 2020, 27, 1–10.

- Campos-Carrillo, A.; Weitzel, J.N.; Sahoo, P.; Rockne, R.; Mokhnatkin, J.V.; Murtaza, M.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA as an early cancer detection tool. Pharmacol Ther. 2020, 207, 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhyam, M. and Gupta, A.K. A Review on the Clinical Utility of PSA in Cancer Prostate. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2012, 3, 120–129. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumbrava, E.I.; Meric-Bernstam, F. Personalized cancer therapy leveraging a knowledge base for clinical decision-making. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2018, 4, a001578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).