1. Introduction

Childhood obesity is a serious problem in the United States putting children and adolescents at risk for poor health. A growing body of research suggests that the risk for childhood and adolescent obesity appears during the early years. Children with a high BMI level or who are overweight or obese in their early years are more likely to be overweight or obese in the later years of their lives [

1,

2]. For US children and adolescents aged 2-19 years in 2017-2020, the prevalence of obesity was 19.7% with an obesity prevalence of 12.7% among 2- to 5-year-olds [

3]. Early childhood has been identified as a critical period for developing interventions to promote healthy eating preferences and physical activity (PA) patterns [

4,

5] – two major protective/preventive behaviors for the prevention of the early onset of obesity.

Intervention-based obesity prevention techniques are found to be effective in promoting children’s PA in the early years. Hands-on gardening, which is found to be associated with higher levels of PA for adults [

6,

7] and school-agers [

8,

9] can also be an effective intervention-based obesity prevention technique during early childhood. Two recent studies conducted in North Carolina (NC) [

10,

11] found positive associations between hands-on gardening and both PA and healthy eating preferences for preschoolers attending center-based childcare. These are among the very few studies that investigated the potential role of gardening in licensed center-based childcare facilities for preventing obesity during the early years of childhood. However, more research is needed to understand whether such positive associations (between hands-on gardening and PA) would extend in different climate zones – especially in arid or semi-arid climates where FV gardening is more challenging compared to a humid subtropical climate zone like NC.

Texas has the second (after New Mexico) highest concentration (39.1%) of the Hispanic and Latino population among all the states in the US. Among preschoolers (2-5 years), Latinos are three times as likely to be obese as Caucasian [

12]. West Texas, for its semi-arid climate and high percentage of Hispanic and Latino population (37.1%), provides a unique site to investigate the effectiveness of hands-on FV gardening for advancing PA of children. The success (or failure) of gardening-based intervention for preventing obesity in early years in this region can provide valuable insights for similar intervention in other areas of the U.S.

The association between childcare attendance and risk of obesity in children [

13,

14,

15] is of critical importance and demands special attention. Of the 21 million children in the US from birth through age 5 participating in various weekly non-parental care arrangements, 62% (more than 13 million in number) attend licensed childcare centers and spend most of their waking hours in those facilities [

16]. Also, the most common location for children’s primary center-based care arrangement was a building of its own (42%) [

16] where gardens can be installed conveniently. Preschool-age, defined by the age range of 3-5 years [

17], is a time when children start to learn following instructions, asking and answering simple question, follow rules or take turns in games/lessons with other children, etc. [

4] – making it an ideal age range for observing/experimenting the impacts of hands-on gardening on behavioral outcomes.

To examine the effectiveness of hands-on gardening intervention in licensed childcare centers in promoting preschoolers’ PA in a semi-arid climate zone with a high concentration of Hispanic families, this study conducted an experimental research with eight childcare centers and one hundred forty-nine children (n=149) in Lubbock County located in West Texas. The study aimed to corroborate findings of the NC studies and investigate whether the positive association between childcare hands-on gardening and preschoolers’ PA extends to a semi-arid climate zone with high percentage of Hispanic families and children.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The proposed project adopts a research design of Randomized Two Group Pre- and Post-Test Experiment [

18] as shown in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Two Group Pre and Post-Test Experiment.

Table 1.

Two Group Pre and Post-Test Experiment.

| Group |

Pre-test |

Treatment |

Post-test |

| Experimental group = E |

O1

|

X |

O2

|

| Control Group = C |

O1

|

|

O2

|

The key concept behind this design comprises randomly assigning subjects (childcare centers) to two groups, an experimental, and a control group. Eight childcare centers were randomly assigned to two groups (4 centers per group). Both groups were pre- and post-tested for children’s PA. However, the experimental group received the treatment – a hands-on FV gardening intervention. Randomization, here, was supposed to ensure that differences that might appear in the posttest would be the result of the experimental variable rather than the possible difference between the two groups to start with [

18]. This classical type of experimental design has strong internal validity. The selection of this research design allowed the research team to compare the final post-test results, giving an idea of the overall effectiveness of the hands-on FV gardening intervention for children’s PA. The research team was able to analyze how both groups changed from pretest to posttest and whether one, both or neither performed differently in terms of child outcome measures on PA.

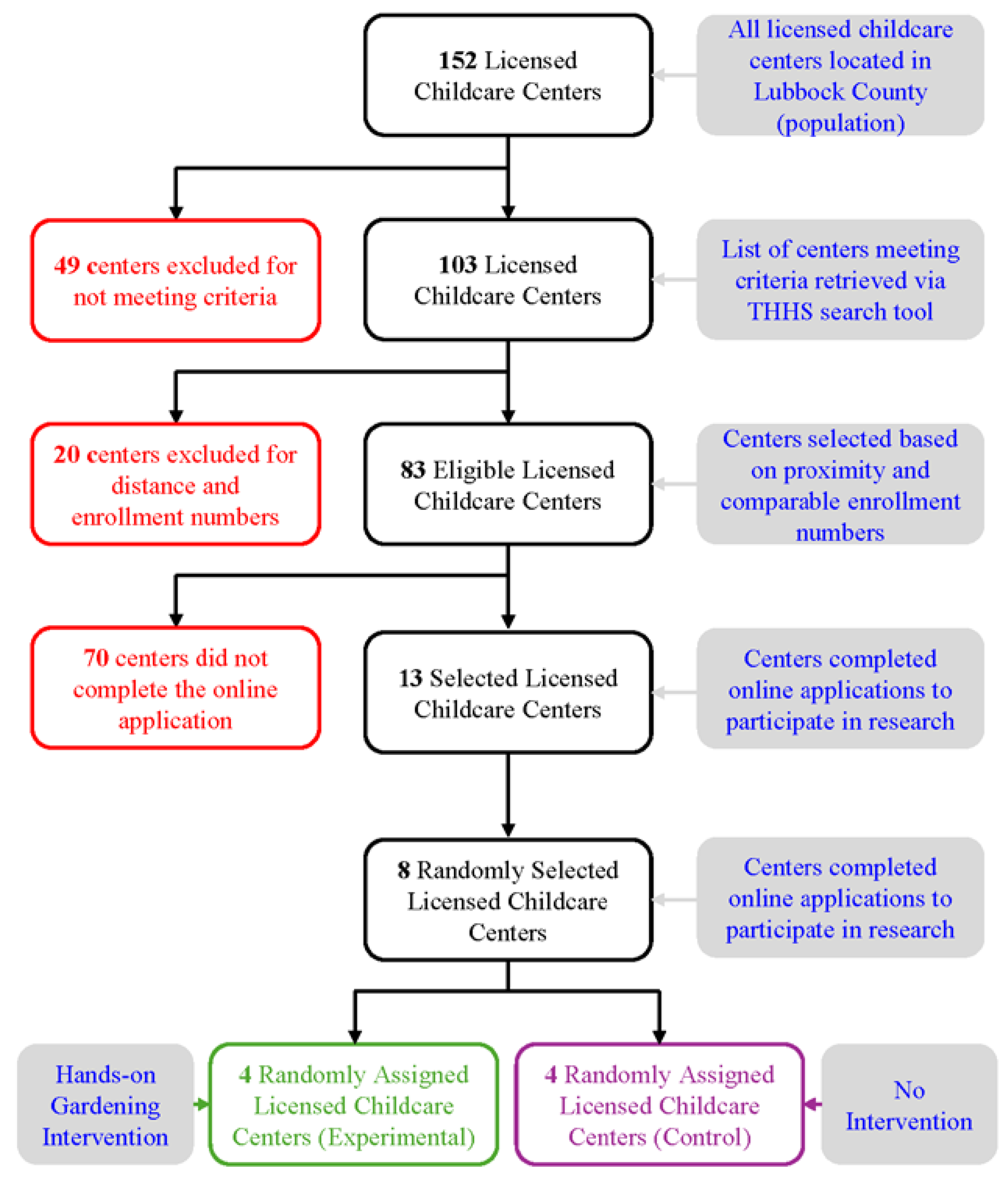

2.2. Participating Childcare Sites: Selection and Random Assignment to Groups

The selection criteria for licensed childcare centers for the research included – 1) centers must be located in Lubbock County, West Texas (which falls within the semi-arid climate zone), 2) centers holding a full permit issued by the CCR (Child Care Regulation) of Texas Health and Human Services (THHS) during the study phase (to ensure compatibility of participating centers), 3) centers must enroll preschool-aged (3-5 years old) children and have separate classroom for preschoolers (for the feasibility of enrollment of child subjects and data collection), and 4) centers must accept childcare subsidies (to ensure children from low-income families will also have the opportunity to enroll in the research and participating centers are comparable in terms of family income). A list of 103 licensed childcare centers located in Lubbock County in West Texas was retrieved from THHS’s online childcare search tool [

19] with the search criteria mentioned above. The list was scrutinized and further reduced to 83 eligible centers based on proximity and enrollment numbers. Driving distance from the university campus was critical as the research team needed to visit the centers several times for data collection and building the gardens. Centers were also scrutinized for their capacity (enrollment numbers) and low-capacity ones were excluded to ensure childcare centers enrolled in the study are comparable in sample size. With the help of the Texas Workforce Commission (TWC), an online call for application was sent to the 83 eligible childcare centers. Only 13 completed applications were received out of those 83. Eight centers were randomly selected from those 13 and then randomly assigned to two groups – the experimental group with 4 childcare centers who received the hands-on garden intervention on year 1 (2022) and the control group with 4 childcare centers who did not receive the intervention in year 1 (2022) but received it in year 2 (2023). This arrangement ensured an experimental model in 2022 and an opportunity to compare pre- and post-intervention PA levels of children in the experimental (treatment) group and the control (non-treatment) group. The control group received the hands-on garden intervention a year later in 2023 to ensure child participants in those 4 centers are not deprived of opportunities to participate in gardening. The following diagram (

Figure 1) shows how childcare centers and child subjects were recruited in the study.

2.3. Participating Children

In the selected eight childcare centers located in Lubbock County, Texas, parents received an invitation letter through the selected childcare center mail system to include their children in the study. The electronic and/or printed invitation letter included a brief description of the research and its potential benefits. Written consent forms (with one extra copy per child) were distributed to all parents in 3-5 years of age children's classrooms in the participating centers by respective classroom teachers. Parents who agreed for their child(ren) to participate signed and returned the consent forms at their convenience in a designated box in the classrooms. The research team collected signed consent forms from the designated box with the permission of the classroom teacher. Children aged 3-5 years were only eligible to be enrolled in the research. A total of 185 children with parental approvals were initially enrolled in the study – 93 children in the Experimental Group (E) centers and 92 in the Control Group (C) centers.

Valid ActiGraph data, however, were retrieved from a total of 149 children (n = 149) – 81 children from the Experimental Group (E) centers and 68 in the Control Group (C) centers. ActiGraph data from 36 children (12 in the Experimental Group and 24 in the Control Group) were deemed unusable for various reasons described in the limitation section of the paper.

Among child participants, 53% were boys and 47% girls. The proportion of boys and girls in the Experimental Group (55% and 45% respectively) was comparable with and similar to the Control Group (56% and 44%). The average age of child participants was 50 months with the Experimental Group (E) children averaging 52 months and the Control Group (C) children 48 months during the start of the study. We were also interested about the participation (%) of Latino and/or Hispanic children (and families) in our study because of potential health disparities and obesity risks of Hispanic and Latino children as discussed earlier. As shown in

Table 1, the percents of participating Hispanic and/or Latino children in the Experimental Group (37%) and the Control Group (43%) were representative of Texas demographics of 39.1% of Hispanic and Latino population in general (2

nd highest Hispanic and Latino concentration among all 50 states).

Table 1.

Ethnic Distribution of Participants.

Table 1.

Ethnic Distribution of Participants.

| Ethnicity |

Experimental Group (E) |

Control Group (C) |

| Non-Hispanic White or Euro-American |

41% |

30% |

| Black, Afro-Caribbean, or African American |

3% |

8% |

| Latino and/or Hispanic American |

37% |

43% |

| East Asian or Asian American |

5% |

0% |

| South Asian or Indian American |

7% |

11% |

| Middle Eastern or Arab American |

2% |

0% |

| Multi-racial |

1% |

2% |

| Other |

4% |

6% |

2.4. Variables

2.4.1. Independent Variable: The Garden Intervention

The intervention for the Experimental Group (E) comprised of a standardized FV garden component with six raised garden beds, designated FV cultivation and children’s hands-on participation in FV gardening with their teachers guided by a Garden Activity Guide (taylored for the Semi-Arid Climate Zone) created by TTU’s partnering organization the Natural Learning Initiative (NLI) at NC State University. The four FV gardens in the four Experimental Group (E) centers were built at the same time frame by the research team. The selection of FV included six vegetables: cucumbers, green beans, green peppers, tomatoes, yellow squash, and zucchini, and five fruits: blackberries, blueberries, cantaloupe, strawberries, and watermelon. The class teachers of participating preschool classrooms in the Experimental Group (E) led implementing the Garden Activity Guide with their children which contained 12 gardening tasks suitable for the preschool age group (3-5 years old). The activities were categorized under three primary themes: Preparation, Maintenance, and Harvesting/Consumption withhands-on tasks ranging from inspecting seeds, readying garden plots to watering, weeding, and harvesting. Teachers led these activities with children for a 30 minutes outdoor session, three times per weekduring the entire gardening season (late spring to early summer). The four Control Group (C) centers did not receive this intervention in Year 1 of the research. They received the intervention in Year 2. However, this paper is concerned with the data we collected in year 1 comparing PA measures bentween the Experimental (E) and Control Group (C) children before and after the intervention to investigate whether hands-on gardening contribute to significantly increased PA levels of children.

2.4.2. Dependent Variable: Physical Activity

Physical activity was assessed via the wActiSleep-BT (Actigraph Corp.) accelerometer, which is a 3-axis activity monitor worn on the wrist of the participant that provides a measure of the frequency, intensity, and duration of physical activity. The wActiSleep-BT is widely used among the exercise and psychological sciences, has documented validity [

20], and data collected using the wActiSleep-BT correlates highly with similar methods of measurement such as doubly labeled water (DLW) and indirect calorimetry [

21,

22]. Physical activity counts were recorded at a sample frequency of 60 Hz, at 1-second epochs in order to increase measurement accuracy. Participants were asked to wear accelerometers on the wrist corresponding to their non-dominant hand for five days during the entire day (both waking hours and during sleep), and to return the accelerometers to study personnel after the 5-day time period. All participating children in both groups (Experimental and Control) attending the eight center wore the accelerometers on the same 5 days before and after the intervention (a total of 10 days). For each participant who wore the accelerometers, research staff recorded the dates and times that each accelerometer was given to the child and attached to their wrist, and when the accelerometer was removed. ActilifeTM Software was utilized to assess the total wear time for each participant and to complete physical activity estimates.

2.5. Data Collection Methods

The research team conducted several preoperational activities before data collection. The TTU research team visited the centers, met with the directors and teachers and completed collecting all signed consent forms. Once all the consent forms were collected, the research team created separate lists of participating children for each of the eight participating centers. In those lists, all children were assigned unique random IDs. Stickers of those unique random IDs of children were attached to the accelerometer monitors. Unique random IDs ensured that same accelerometer monitors were assigned to children during pre- and post-intervention data collection sessions. The unique random IDs also ensured data anonymity. Children started wearing the accelerometers on a Monday and wore them continuously till the Friday afternoon of that week. To initiate the data collection, a research team member will visit a preschool classroom of a participating childcare center on Monday morning at 8:30 am. The researcher carried all accelerometer monitors assigned with unique random IDs. He/she provided the classroom teacher with a list of children and their assigned unique random IDs. The list also had blank columns for recording times when children started wearing the accelerometers and when they took them off on Friday. The accelerometers were attached to the non-dominant wrist of each child with a static nylon belt by the trained researcher. The classroom teacher helped the researcher identify children by names and attaching the assigned accelerometer monitors by matching the unique random IDs. The classroom teacher also recorded times of taking accelerometers off on Friday afternoon. The researcher visited the center on the following Monday to collect all the accelerometers from the teacher. This process was repeated during the post-intervention data collection session. Teachers were compensated for each session for their help in the data collection process.

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Analyses

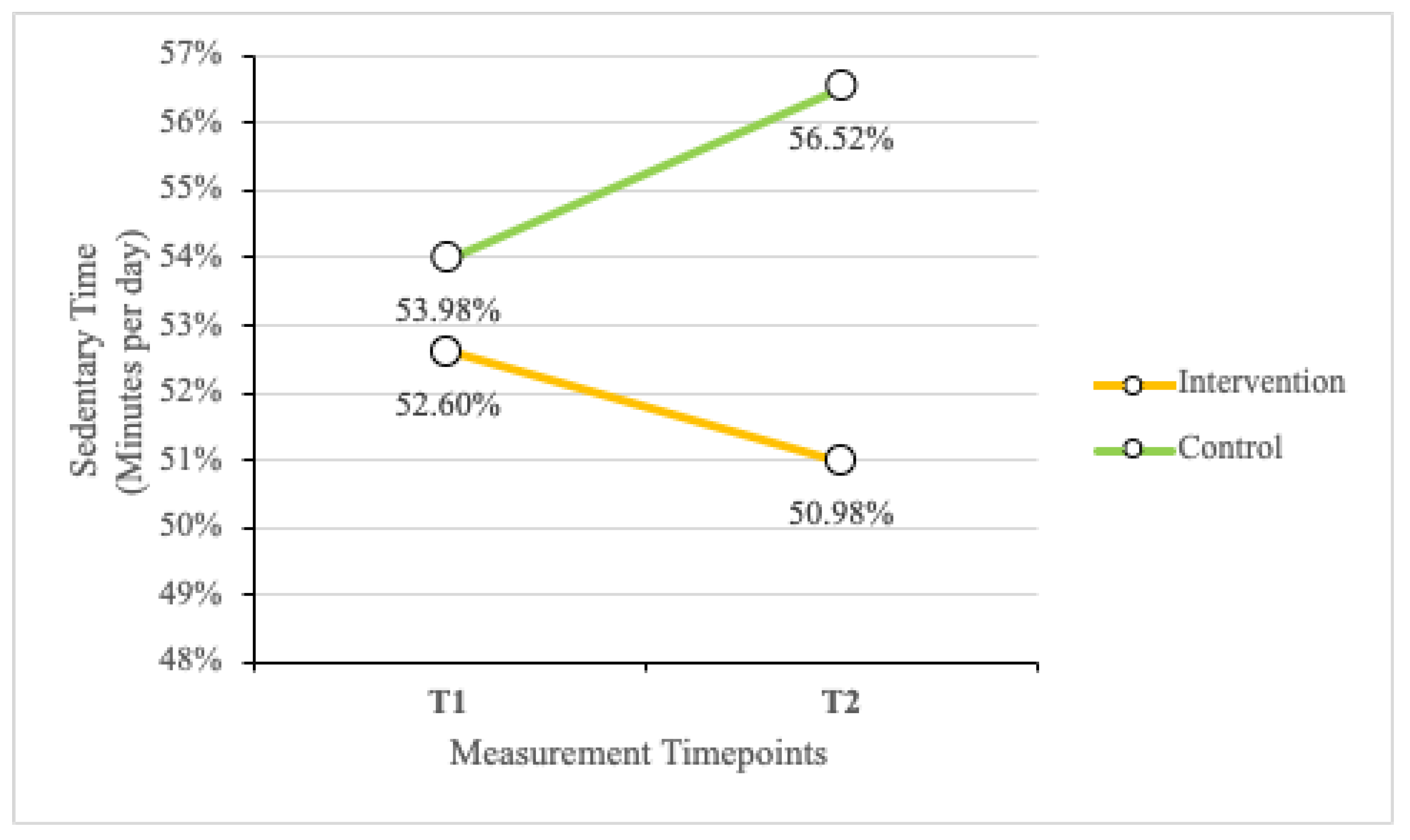

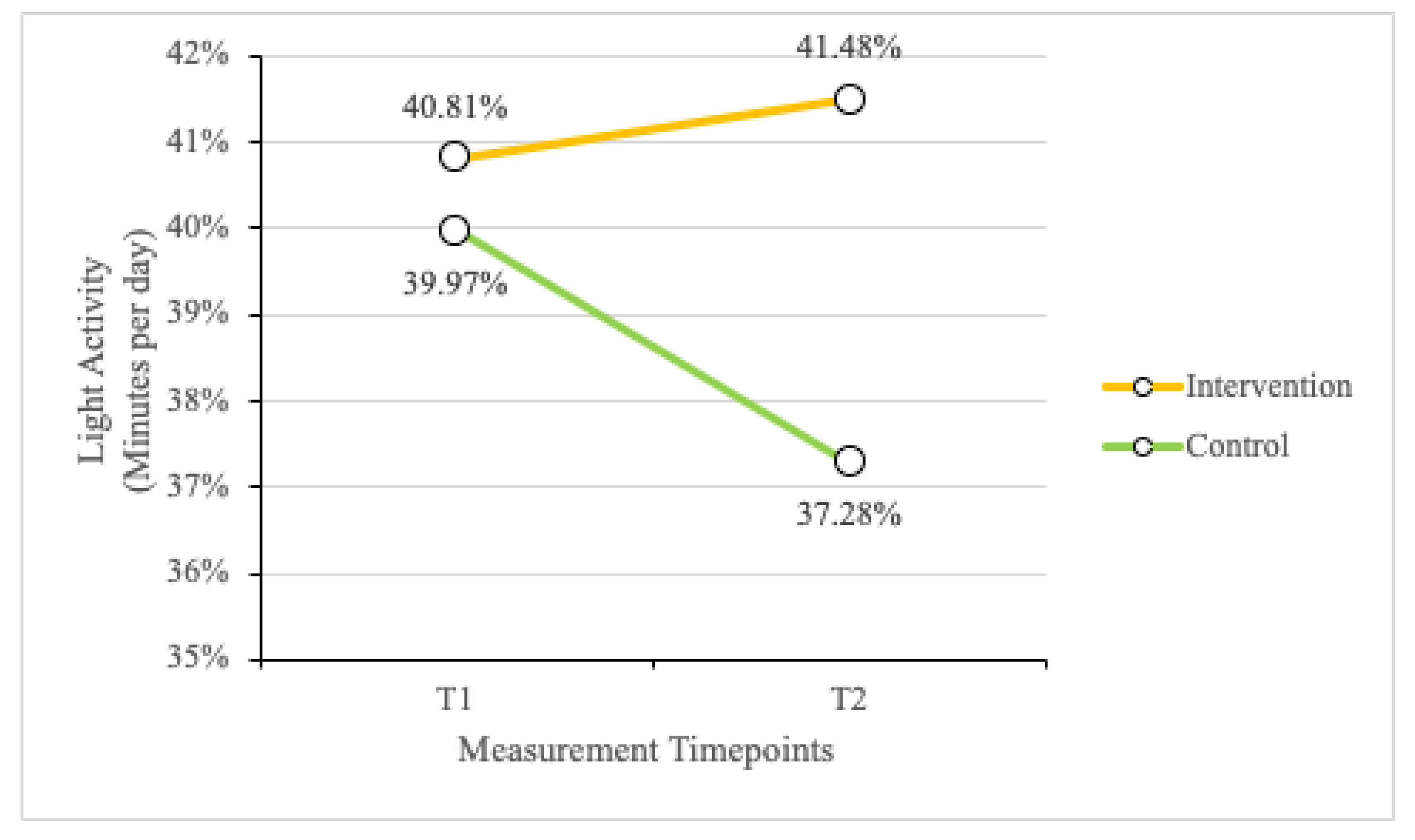

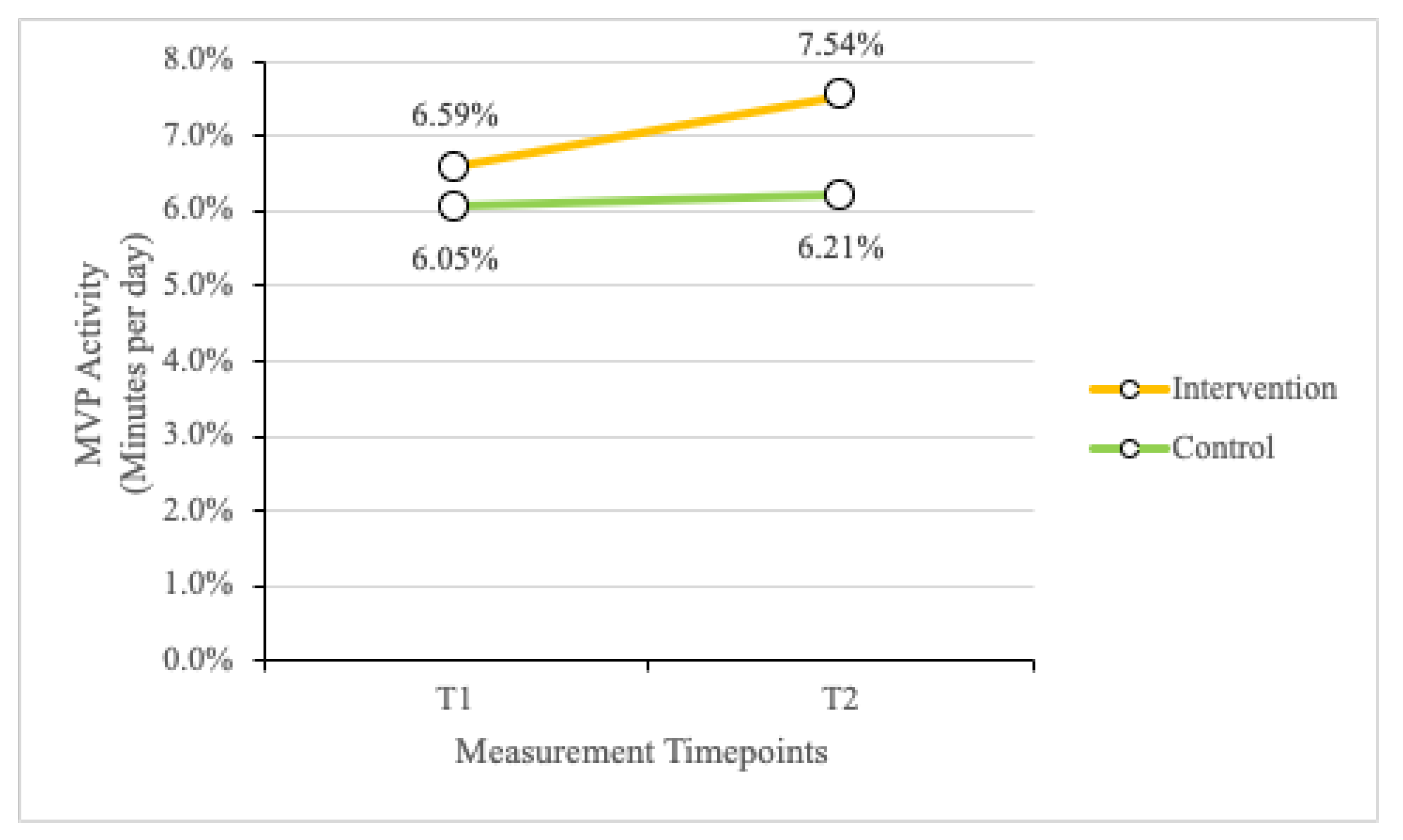

All activity levels (i.e., sedentary, light, and moderate to vigorous or MVPA) are presented as a percentage of valid wear time spent in each category to account for between-group differences in total wear time. Bivariate correlations were conducted to assess associations of age at Time 1 (before the hands-on gardening intervention), age at Time 2 (after the hands-on gardening intervention), and activity. It most be noted for clarity that the intervention (hands-on gardening) in this research was a continuous process and during Time 2, children at the Experimental Group (E) centers were still actively participating in hands-on gardening activities with their teachers. Time 2 data, therefore, represents Group-E children’s PA during the intervention although it is referred to as post-intervention data in this paper. Repeated-measures three-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were performed to estimate interactions of group, time, and demographic variables (i.e., sex, age, and ethnicity) on activity. Repeated-measures two-way ANOVAs were performed to compare differences between group and time on activity throughout the total study duration, activity occurring only during school time, and activity occurring only outside of school time (e.g., at home, during other activities).

There were 24 participants with complete data at Time 1 and Time 2 for the intervention group and 17 with complete data at Time 1 and Time 2 for the control group. One center assigned to the control group did not allow children to take the ActiGraphs home after school. Thus, this group was only included in analyses assessing activity during school. To assess between-group differences between Hispanic and non-Hispanic participants (given the available sample size), participant ethnicity was dichotomized so that all individuals who did not identify as Hispanic were included in the non-Hispanic group.

3.2. Identification of Covariates

To estimate associations between age and PA, bivariate correlations were performed. As noted in

Table 2, a significant and positive correlation was found between age at Time 1 (r = 0.23, p < .01) and light physical activity at Time 1 (r = 0.23, p < .01). Age at Time 2 (r = 0.26, p < .05) also demonstrated a significant and positive correlation with light physical activity at Time 2. Age at Time 1 (r = 0.42, p < .01) and Time 2 (r = 0.43, p < .01) was significantly and positively correlated with MVPA at Time 1. Thus, ages at Time 1 and Time 2 were included as covariates in subsequent models. Further, there were no between-group differences between Hispanic and non-Hispanic participants for sedentary (p = .11), light (p = .11), and MVPA (p = .52;

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

As seen in

Table 3, there was no significant interaction between gender, group, and percent of time spent in sedentary activity (p = .30), light activity (p = .91), or MVPA (p = .53).

Further, as seen in

Table 4, there were no between-group differences between Hispanic and non-Hispanic participants for sedentary (p = .11), light (p = .11), and MVPA (p = .52).

3.2. Primary Analyses

Overall, there was no significant interaction between group and time on the percentage of sedentary behavior (p = .15), light activity (p = .24), or MVPA (p = .15) throughout the study duration (i.e., during school and out of school time, combined) while controlling for age at Time 1 and Time 2 (

Table 5).

Regarding activity that only occurred during school time (

Table 6 and

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), there was a significant interaction between group and time on sedentary behavior (F = 4.33, p = .045, η

2 = .110), controlling for age at Times 1 and 2. Pairwise comparisons were not significant. Specifically, neither the intervention group (p = .41) nor the control group (p = .20) participated in more sedentary behavior at Time 2 than at Time 1. However, comparing groups across time points can mask paterns of change, because the difference across each time point is smaller than the net difference between the groups overtime. Thus, the signifant interaction is emphasized here.

There were no significant interactions between group and time on the percentage of sedentary behavior (p = .30), light activity (p = .63), or MVPA (p = .59) outside of school time (

Table 7).

4. Discussion

This research compared preschoolers’ PA as an experimental outcome of their participation (or non-participation) in hands-on FV gardening activities while attending childcare centers in a semi-arid climate zone. The study also took a novel approach to investigate PA increases/changes as measured by accelerometers as a potential outcome of childcare hands-on gardening during childcare time (referred to as ‘school time’), home time, and the overall wear time (5 days continuously) referred to as ‘total time’. Analyzing data at these three levels make this study unique compared to relevant other contemporary research. The NC study [

10] investigated similar effects only during school time (accelerometers were taken off before leaving childcare facilities) but it emphasized the need for investigating potential ‘spillover effects’ beyond school time at home. This study attempted to investigate this ‘spillover effect’ [

23] by collecting PA data of children beyond school time while they were engaged in hands-on gardening at their respective childcare centers (Experimental Group). School gardens provide a dynamic outdoor environment where preschoolers can be physically active. Preschoolers can share their daily activities at childcare centers with their parents. It is possible that their enthusiasm about gardening, harvesting, tasting FV that they grew by themselves are transmitted to their household/family culture of home gardening, outdoor times, and daily physical activity. There is no previous study that investigated spillover effects of hands-on gardening at preschool age (3 to 5 years). We did not find any significant differences in sedentary, light, and MVPA between the experimental (gardening) and control (non-gardening) groups of children in home time and total time. But this finding does not eliminate the need for investigating the ‘spillover effects’ of hands-on gardening on preschoolers’ PA. Our study was limited by a smaller sample size and ‘home time’ PA calculation was interrupted by one center not allowing its participating children to wear accelerometers at home – further reducing the sample size for a meaningful analysis.

The NC study reported significant intervention effect for MVPA (p < 0.0001) and sedentary minutes (p = 0.0004), with children at intervention (gardening) centers acquiring approximately 6 min more MVPA and 14 min less sedentary time each day while attending their respective childcare centers (school time) [

10]. We did not find any significant differences (p = 0.15) between the experimental (gardening) and the control (non-gardening) group (

Table 6 and

Figure 4). Both groups experienced an increase in their MVPA (%). The positive association indicates the experimental group enjoyed a higher increase in their MVPA but not significantly more than the control group. However, like the NC study, we also found a significant reduction in sedentary time (p = 0.045) for the experimental group of children who participated in hands-on gardening. The only difference being the significance levels – the NC study found the difference to be highly significant (p = 0.0004) while our study found a moderate significant difference at p ≤ 0.05 level. This similar finding in reduction of children’s sedentary behaviors as an experimental outcome of hands-on gardening is meaningful in many ways. Diverse opportunities for PA are important in childcare centers, especially in outdoor environments. Children’s PA requirements, interests, and motivations can be different and an childcare outdoor environment with diverse PA

affordances can ensure that children are engaged in moderate/light to vigorous PAs. Hands-on gardening brings a variety of PA opportunities for children and adds to diversified PA affordances for preschoolers. A significant reduction in sedentary time outdoors supports this hypothesis in both the NC study (in humid subtropical climate zone) and the Texas one (in semi-arid climate zone). If hands-on gardening can contribute to reduced sedentary behaviors of preschoolers in their outdoor times while attending childcare centers in two drastically different climate zones, it should be considered as a nationally implementable early health intervention for preventing childhood obesity.

Our other important finding, though not highly significant in statistical terms, implies the value of adding hands-on gardening in childcare outdoor activities to increase light activity of children. The NC study reported no significant differences in light physical activity between the two groups of children – the experimental (with gardening intervention) vs the control (no gardening intervention) groups. Our ‘school time’ analyses (

Table 6 and

Figure 3) shows that children exposed to hands-on gardening experienced an increase in their light activity compared to the non-gardening group. This difference is statistically significant at p ≤ 0.1 (p = 0.078). This denotes a weak evidence or trend but given our small sample size (n = 149), this difference demands in-depth discussion.

To understand this finding, we investigated the list of activities defined by the 5-levels CARS scale [

24] under Level 2 (low; easy) and Level 3 (medium; moderate). Movement behaviors that are closely associated with gardening fall mostly under Level 2 and Level 3 (

Table 8). Since the coding of the CARS scale is validated by accelerometry cut points [

25]; this observation of a significant (p ≤ 0.1) p increase of light physical activity due to participation in hands-on gardening is meaningful. Accelerometers can measure the PA levels but cannot predict the nature/type of PAs children were involved in. Future research comparing accelerometry data and observational data of preschoolers’ PA while engaging in hands-on gardening will be valuable to get a more in-depth understanding of gardening-based PA.

One other key objective of the study was to investigate whether changes in PA as an outcome of hands-on gardening were significantly different between Hispanic vs non-Hispanic preschoolers. We did not find any statistically significant differences between the two groups. The health disparities and higher risks of childhood obesity in Hispanic children inspired this investigation. But we acknowledge that our finding with a limited sample size does not eliminate the need for further investigation. More studies with larger sample sizes are needed.

5. Limitations

The challenges and the limitations of the study are equally important discussions that shed light on many realities of intervention research involving preschoolers attending childcare centers. We repeatedly mention our limitation related to a small sample size, but this limitation is caused by a complex set of reasons.

First, we faced challenges recruiting childcare centers for this study. Although we built and managed the FV gardens in the Experimental Group (E) centers and provided participation support costs to all teachers for each data collection session, very few centers were fully on board with participation. Childcare centers are consistently challenged by teacher turnover and limited resources. Texas has one of the highest turnover rates in early childhood education at over 20% [

26]. Even when a childcare center leadership (owner/director) are enthusiastic to implement hands-on gardening in their outdoor environment, they are overwhelmed by any ‘extra effort’ while constantly navigating through the challenges of finding the manpower to run their enterprise. Hands-on gardening as a health intervention is long-term and complex. For tracking data related to the intervention (children’s participation in hands-on gardening) we had to depend on classroom teachers. Although they were compensated for their participation and efforts, numerous times we had to face challenges of classroom teachers leaving the childcare center and reassigning new teachers in the study.

Second, children and families leaving their childcare centers created challenges especially for collecting data in the post-intervention phase. In this phase of data collection after the garden intervention, it was documented that there was a 12% loss of sample size in the experimental group due to non-continuation. Likewise, the control group had a loss of 8% of their sample data for the same reasons – children leaving or graduating from their respective childcare centers.

Third, during each data-collection time, the children were supposed to wear accelerometers continuously for five consecutive days. In the recorded final accelerometer data, 12% of the sample data from the experimental group and 4% from the control group were lost due to missing data resulting from non-wear (i.e., children refusing to wear the accelerometers for an extended period, or they simply lost the devices in their home environments). This showed how challenging it is to collect beyond-school PA data of preschoolers attending childcare centers. One of the authors (J.V.) of this study has extensive experience of using accelerometers for collecting continuous PA data of school-agers and never experienced data and device loses at this proportion. It indicates that alternative methods are needed for collecting continuous PA data of younger children.

Although we were able to recruit 185 children for the study (received signed consent forms from parents), due to the three reasons above, data from only 145 children was usable for statistical analyses of overall interactions. For pairwise comparison, this sample size was further reduced to only 41, limiting our ability to conduct any meaningful analyses at the individual level.

6. Conclusions

Behavioral habits related to food and physical activity are established early in life [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Therefore, introducing young children to fruit and vegetable (FV) gardening may help to set positive life course trajectories toward physical activity and healthy eating. CDC recommends that preschoolers should spend at least 180 minutes (3 hours) a day doing a variety of physical activities including active and outdoor play. The 180 minutes should include at least 60 minutes (1 hour) of MVPA; meaning the daily recommended light PA for preschoolers is 120 minutes. Many US children (0-5 years of age) spend most of their waking hours in childcare centers. The cumulative findings of the NC and TX studies (hands-on gardening increase preschoolers’ PA while decreasing sedentary times) have strong policy implications. Because childcare centers are policy-sensitive institutions, evidence underscoring the benefits of FV gardening may encourage regulators to adopt supportive rules [

31]. With approximately 76% of the U.S. population living in areas with an annual growing season >200 days, a gardening component may be a promising obesity prevention strategy for young children in these regions, where 77% of the U.S. regulated childcare centers are located [

32]. In the changing landscape of financial reality of licensed childcare centers in the U.S., we must find low-cost, sustainable, and feasible health interventions to ensure the health and well-being of young children. A hands-on FV gardening component (found to be successful even in a semi-arid climate zone with relative low rainfall and humidity) should be considered as a feasible health intervention applicable to most U.S. childcare centers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and N.C.; methodology, M.M., N.T., S.A., J.V., and T.H..; formal analysis, T.H. and J.V.; investigation, M.M., N.T., and S.A.; resources, M.M. and J.V.; data curation, N.T. and T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, T.H., J.V., N.C., N.T., and S.A.; visualization, T.H. and N.T.; supervision, M.M. and J.V.; project administration, M.M. and N.T.; funding acquisition, M.M, J.V., and N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the intramural research program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Non-Land-Grant Colleges of Agriculture (NLGCA) program to Texas Tech University (2020-70001-31277).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Texas Tech University, IRB#2020-346, approved on April 30, 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author (M.M.).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge the contributions of TTU MLA students Garrett Farrow and Umme Haque in building fruit and vegetable gardens at childcare centers and data collection activities. We also acknowledge administrative support from Nancy Hubbard, Professor Eric Bernard, and Professor Leehu Loon. We are grateful to childcare center directors, owners, teachers, parents, and children for their participation. Lastly, we will take this opportunity to remember late Professor Charles Klein who was a Co-PI of the USDA grant that supported this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kitsantas, P.; Gaffney, K.F. Risk profiles for overweight/obesity among preschoolers. Early Human Development 2010, 86, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nader, P.R.; O'Brien, M.; Houts, R.; Bradley, R.; Belsky, J.; Crosnoe, R.; Friedman, S.; Mei, Z.; Susman, E.J.; Health, f.t.N.I.o.C.; et al. Identifying Risk for Obesity in Early Childhood. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e594–e601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports 2021. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html (accessed on January 2024).

- Costa, S.; Adams, J.; Phillips, V.; Benjamin Neelon, S.E. The relationship between childcare and adiposity, body mass and obesity-related risk factors: protocol for a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Systematic Reviews 2016, 5, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicklett, E.J.; Anderson, L.A.; Yen, I.H. Gardening Activities and Physical Health Among Older Adults: A Review of the Evidence. J Appl Gerontol 2016, 35, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, A.; Warren, J.L.; McIntosh, A.; Hoelscher, D.; Ory, M.G.; Jovanovic, C.; Lopez, M.; Whittlesey, L.; Kirk, A.; Walton, C.; et al. Impact of a Gardening and Physical Activity Intervention in Title 1 Schools: The TGEG Study. Childhood Obesity 2020, 16, S-44-S-54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Hamzah, S.H.; Gu, E.; Wang, H.; Xi, Y.; Sun, M.; Rong, S.; Lin, Q. Is School Gardening Combined with Physical Activity Intervention Effective for Improving Childhood Obesity? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.N.; Pérez, A.; Asigbee, F.M.; Landry, M.J.; Vandyousefi, S.; Ghaddar, R.; Hoover, A.; Jeans, M.; Nikah, K.; Fischer, B.; et al. School-based gardening, cooking and nutrition intervention increased vegetable intake but did not reduce BMI: Texas sprouts - a cluster randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2021, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, N.M.; Cosco, N.G.; Hales, D.; Monsur, M.; Moore, R.C. Gardening in Childcare Centers: A Randomized Controlled Trial Examining the Effects of a Garden Intervention on Physical Activity among Children Aged 3–5 Years in North Carolina. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco, N.G.; Wells, N.M.; Zhang, D.; Goodell, L.S.; Monsur, M.; Xu, T.; Moore, R.C. Hands-on childcare garden intervention: A randomized controlled trial to assess effects on fruit and vegetable identification, liking, and consumption among children aged 3–5 years in North Carolina. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, L.M.; Rayburn, J.; Martin, A. State of obesity: Better policies for a healthier America: 2016. Available online: http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101698962 (accessed on January 2024).

- Geoffroy, M.-C.; Power, C.; Touchette, E.; Dubois, L.; Boivin, M.; Séguin, J.R.; Tremblay, R.E.; Côté, S.M. Childcare and Overweight or Obesity over 10 Years of Follow-Up. The Journal of Pediatrics 2013, 162, 753–758.e751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isong, I.A.; Richmond, T.; Kawachi, I.; Avendaño, M. Childcare Attendance and Obesity Risk. Pediatrics 2016, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrady, M.E.; Mitchell, M.J.; Theodore, S.N.; Sersion, B.; Holtzapple, E. Preschool Participation and BMI at Kindergarten Entry: The Case for Early Behavioral Intervention. Journal of Obesity 2010, 2010, 360407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Natzke, L. Early Childhood Program Participation: 2019. First Look. NCES 2020-075; National center for education statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/positiveparenting/preschoolers.html (accessed on January 2024).

- Shuttleworth, M. Pretest-Posttest Designs. Available online: https://explorable.com/pretest-posttest-designs (accessed on January 2024).

- THHS (2024). Available online: https://childcare.hhs.texas.gov/Child_Care/Search_Texas_Child_Care/ppFacilitySearchDayCare.asp (accessed on January 2024).

- Sasaki, J.E.; John, D.; Freedson, P.S. Validation and comparison of ActiGraph activity monitors. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2011, 14, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimmy, G.; Seiler, R.; Mäder, U. Development and validation of GT3X accelerometer cut-off points in 5-to 9-year-old children based on indirect calorimetry measurements. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin und Sporttraumatologie 2013, 61, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasqui, G.; Westerterp, K.R. Physical activity assessment with accelerometers: an evaluation against doubly labeled water. Obesity 2007, 15, 2371–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francetic, I.; Meacock, R.; Elliott, J.; Kristensen, S.R.; Britteon, P.; Lugo-Palacios, D.G.; Wilson, P.; Sutton, M. Framework for identification and measurement of spillover effects in policy implementation: intended non-intended targeted non-targeted spillovers (INTENTS). Implementation Science Communications 2022, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, J.; Greaves, K.; Hoyt, M.; Baranowski, T. Children's Activity Rating Scale (CARS): Description and Calibration. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 1990, 61, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hislop, J.F.; Bulley, C.; Mercer, T.H.; Reilly, J.J. Comparison of Accelerometry Cut Points for Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Preschool Children: A Validation Study. Pediatric Exercise Science 2012, 24, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Texas Turnover Rate for Early Childhood Education. Available online: https://texestest.org/texas-early-education-turnover-rate/#:~:text=It%20makes%20sense%2C%20then%2C%20that,rate%2C%20with%20just%208%25 (accessed on January 2024).

- Elder Glen Jr, H.; Shanahan, M.J. The life course and human development. In Handbook of child psychology; 1998; Volume 1, pp. 939-991.

- Wells, N.M.; Lekies, K.S. Nature and the life course: Pathways from childhood nature experiences to adult environmentalism. Children, youth and environments 2006, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wethington, E. An Overview of the Life Course Perspective: Implications for Health and Nutrition. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2005, 37, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton, B.; Gotlib, I.H. Trajectories and turning points over the life course: concepts and themes. In Stress and Adversity over the Life Course: Trajectories and Turning Points, Wheaton, B., Gotlib, I.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1997; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, P.S.; Walters, K.M.; Igoe, B.M.; Payne, E.C.; Johnson, D.B. Physical Activity Practices, Policies and Environments in Washington State Child Care Settings: Results of a Statewide Survey. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2016, 21, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Child Care, A. Child care in America: 2012 state fact sheets. Available online: https://researchconnections.org/childcare/resources/23722 (accessed on January 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).