1. Introduction

Obesity is a public health problem and a chronic disease that stems from a variety of factors and requires sustained efforts to control. It is a severe threat to health and a significant risk factor for developing and worsening other diseases [

1]. On average, it is responsible for around 3.5 million deaths a year. As well as being considered a chronic disease, it is also a risk factor for numerous other pathologies [

2].

Rising levels of obesity are a significant challenge for public health and obesity is considered a pathology for priority intervention. Given its high prevalence worldwide, the WHO considers it the global epidemic of the 21st century since its growth is occurring equally in developed and developing countries. Globally, WHO statistics show that more than 39% of adults aged 18 and over were overweight in 2016, with more than 13% of individuals suffering from obesity [

3].

Obesity can be treated in various ways, whether with behavioral, pharmacological, or surgical therapy. Bariatric surgery is considered a safe and effective long-term procedure for treating obesity and its comorbidities. Increasingly, this type of surgical intervention is the treatment of choice for people with severe obesity, with or without other associated pathologies [

4].

There are no bariatric surgery guidelines regarding postoperative follow-up using e-health technologies [

5]. It becomes fundamental because, after bariatric surgery, there remains a lifelong threat of regaining weight, and behavioral influences are believed to play a modulating role in this weight gain [

2,

6].

Obesity is a risk factor for sleep disorders, including Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome (OSAS) and insomnia. Bariatric surgery can improve subjective sleep quality and daytime sleepiness that often persists after surgery [

7].

We know that bariatric surgery plays a fundamental role in treating obesity and, consequently, in sleep quality, but we have little evidence regarding the factors related to the improvement or persistence of sleep disorders and how they can be affected by the management and results of the treatment process.

Compromised QoL is one of the main reasons individuals opt for bariatric surgery and is defined as an individual’s perception of their position in life. In this way, it encompasses culture, values, goals, expectations, standards, concerns and the environment in which an individual lives [

8].

In its various forms, E-health makes it possible to boost patient involvement and patient-centered care (PCC). This type of care is recognized as a desirable attribute of health care. It is seen as an approach that considers users’ preferences, needs and values, taking a biopsychosocial perspective based on a solid commitment between the patient and the health professional [

9,

10]. Studies report that, with the implementation of PCC strategies, there have been improvements in clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction, as well as reduced healthcare costs and resource utilization [

11,

12]. However, even with a growing recognition of the value of its potential, it has been reported that there needs to be more guidance available on the use of these strategies for the management of bariatric surgery. The impact of telemedicine on adherence to treatment and follow-up in bariatric surgery remains poorly documented [

13].

According to the WHO, e-health is using information and communication technologies in the health sector in a safe and economically viable way to support health [

14]. It has been implemented and developed worldwide based on information and communication technologies in health. It should be noted that implementing information and communication technologies in the health sector is an active part of the WHO’s agenda on a global scale, with a view to universalization and uniformity between different countries [

15].

Among the various levels of operation of health systems, e-health has been responding, from the organizational restructuring of services to users’ access to care, proving to be an essential element in combating the sustainability problems that often exist in public/private health systems [

16].

In Portugal, implementing e-health has been a fundamental strategy for reforming the health system. It has been recommended as an economic-political instrument under the Economic and Financial Assistance Program agreed between the Portuguese Government and the European Union [

17,

18]. The rapid development of information and communication technologies constitutes an excellent opportunity to reduce costs in the different health sectors and improve efficiency [

18].

Recently, with the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of telemedicine as an e-health tool has been increased. Telemedicine, especially teleconsultation and telemonitoring, refers to providing health services using information and communication technologies [

18]. Telemedicine allows many users to attend routine and follow-up appointments from the comfort of their own homes. In this way, it is possible to share useful clinical information to diagnose, prevent and treat health related problems.

The support of the team of professionals involved in the bariatric surgery process during the pre-and postoperative phases, significantly affects patients’ weight loss results. In addition, there is evidence of improvements in various parameters associated with quality of life and mental health. The team of professionals, a surgeon, nurse, nutritionist and psychologist, educates and supports patients in making lifestyle changes for long-term maintenance and self-management [

16].

Telemedicine and e-health technologies have the potential to enhance the monitoring of bariatric surgery patients, with good results in terms of patient satisfaction, while maintaining a personalized and individualized approach to each patient, promoting the centrality of care. This study aimed to analyze the impact of the use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic on the results of bariatric surgery and users’ satisfaction with this follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This observational, cross-sectional, quantitative study was recruited in February 2023 and data collected from March to April 2023. Retrospective data was collected, analyzed, and evaluated by observing data throughout the postoperative period. This data was then supplemented by data collected after words, making this a cross-sectional observational study.

2.2. Characterization of the Sample

In the database of a Bariatric Center, 108 patients underwent bariatric surgery and made up our population. As inclusion criteria for the sample, participants had to have undergone bariatric surgery in 2020, with follow-up via telemedicine or other e-health technologies and agree to participate in the study. By applying these criteria, we were left with a sample of 80 patients, considered a convenience sample.

Participation was voluntary, and those interested in participating in the study were asked to give their free, informed consent (Appendix A), after which a questionnaire was administered during the telephone interview. Clinical analytical data was consulted to complete the database.

2.3. Instruments

The data collection instrument included four sections.

Section 1 collected sociodemographic, health and weight information.

Section 2 assessed quality of life using the Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System (BAROS). In section 3, we used the Pittsburgh Scale to assess sleep quality and finally, in section 4, we used the questionnaire on user satisfaction with the telephone consultation.

Quality of life: We used the Portuguese version of the WHOQOL-BREF; a 26-item abbreviated version of the WHOQOL-100 assessment. The WHOQOL-BREF assesses QoL across four domains, the physical health, the psychological, the social relationships and the environment domain. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale with the mean score of items within each domain used to calculate the domain score. Domain scores are scaled in a positive direction (ie, higher scores indicate a higher QoL) [

19,

20].

Sleep Quality: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is a self-assessment questionnaire for sleep quality, also aimed at determining various sleep disorders. The original questionnaire consists of nineteen items, which generate seven scoring components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. The sum of the scores for these seven components produces a global score, translating into the final interpretation of sleep quality. The shorter version of the PSQI, with only ten items, reduces the number of questions and does not compromise the overall assessment of sleep quality, so this will be the version used in the study [

21].

Satisfaction with Telemedicine: An eight-dimensional questionnaire, used in validated studies through 16 questions with a Likert scale, was built and validated in Portugal [

22].

2.4. Tasks, Procedures, and Protocols

Individuals who underwent surgery in 2020 at the Hospital do Espírito Santo de Évora, EPE, were approached to assess their willingness to answer the questionnaire. Informed consent was obtained from all participants (Appendix A), guaranteeing the confidentiality of the data. Health and clinical data was consulted through each patient’s electronic medical record. The rest of the data was collected by telephone interview and entered into a form created to minimize data entry errors.

2.5. Variables

The qualitative and quantitative variables to be considered in this study are as follows:

- Clinical Data: Comorbidities associated with obesity (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and OSAS);

- Questionnaires: Quality of life, satisfaction with telemedicine monitoring and perception of sleep quality;

- Other variables: Gender, age, weight, body mass index.

2.6. Statistical Treatment

After defining the hypotheses, the analysis was done using IBM® SPSS® Statistic software, version 28. The sociodemographic characterization of the sample was based on gender and age.

The statistical tests were adapted to each type of variable and relationship to be studied and to the results of the normality tests carried out. Normality tests determine whether a normal distribution guides a set of data for a given random variable. Normality was analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and based on this result, the most appropriate statistical tests were selected. The internal consistency of the questionnaire dimensions was measured using Cronbach’s alpha.

The data collected was productive and various analyses of association and correlation between variables were carried out. The types of tests used for the various hypotheses were based on the results of the normality tests, namely the Chi-square, T-student and ANOVA tests.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

This research was carried out after authorization from the ethics committee, to which a request was addressed and authorized by the hospital’s Board of Directors - CES Opinion no. 010/23 (Appendix A).

Users were invited to participate when contacted by telephone. Those who agreed to participate in the study were subsequently read and given the informed consent form (Appendix A).

About the data collection instruments, the authors have yet to be asked for permission to use them, given their scientific evidence and the fact that they have been published. We consider that the use of these questionnaires is for personal, academic and non-commercial purposes, thus being considered free use whenever the author is mentioned (“Code of Copyright and Related Rights” (CDADC), established by Decree-Law no. 63/85, of March 14).

3. Results

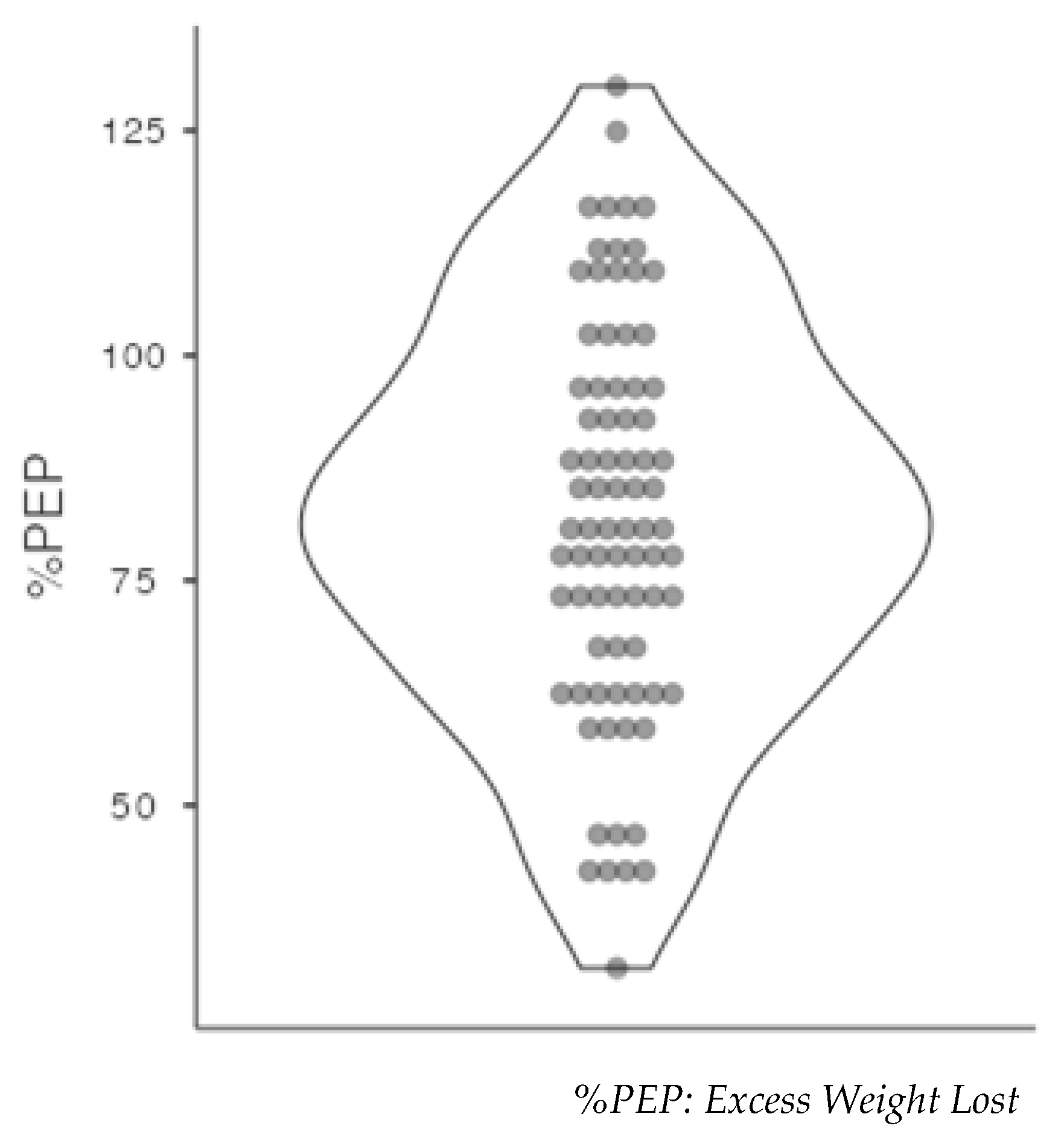

The final sample used for this study included 80 participants who underwent surgery in 2020 using the Gastric Bypass surgical technique. Mostly women were in this sample (n=68; 85%). The average age (±SD) of the sample was 42.7 years (±9.91), and the %PEP (Excess Weight Lost) was higher in women at 83.6% (±22.6) (

Table 1).

Out of 80 subjects, only 8 (10%) did not achieve the 50% loss of excess weight (

Figure 1).

More than three-thirds of the sample had hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, and around a quarter had OSAS. An assessment was made of the total weight lost and the percentage of excess weight lost (

Table 2). The average percentage of weight lost was over 50% (53.1%) and the average percentage of excess weight lost was over 75% (82.2%).

An evolutionary analysis was made of health data and associated comorbidities, particularly metabolic risk factors. This evolution comprises two assessments: Baseline (before surgery) and three years after surgery and after the COVID-19 pandemic. We mostly see a downward trend, with lower values after surgery, with statistically significant values (p <0.001) (

Table 3).

QoL was one of the variables assessed and correlated with telemedicine follow-up. Overall, 75% (n=60) of users had a low QoL and only 25% (n=20) had a good QoL. QoL was characterized in four levels, according to the description and evidence of the BAROS questionnaire (Queiroz et al., 2017), with the highest category prevailing (50%) and QoL in two levels, considering the questionnaire used (Famodu et al., 2018).

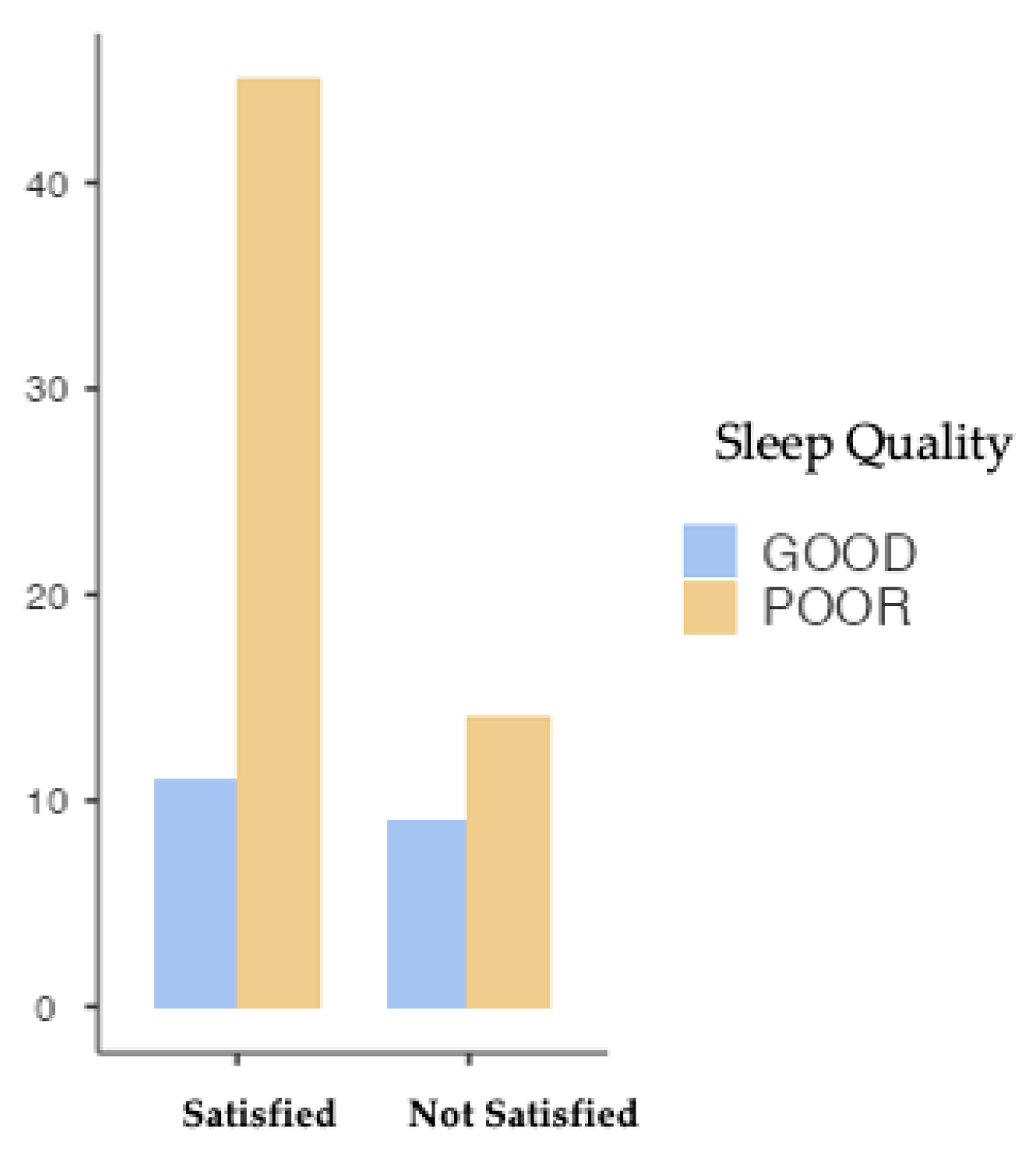

Satisfaction with telemedicine was measured in terms of percentages, with 71.3% of users being satisfied with the follow-up after surgery involving this e-health technology.

The chi-square test was used to assess whether QoS depends on telemedicine satisfaction levels, and a type I error probability of 0.05 was considered in all inferential analyses. A high number of subjects with low QoL (74.7%) was observed if unrelated to telemedicine follow-up (p=0.070; X2= 3.27; Fisher=0.090) (

Figure 2).

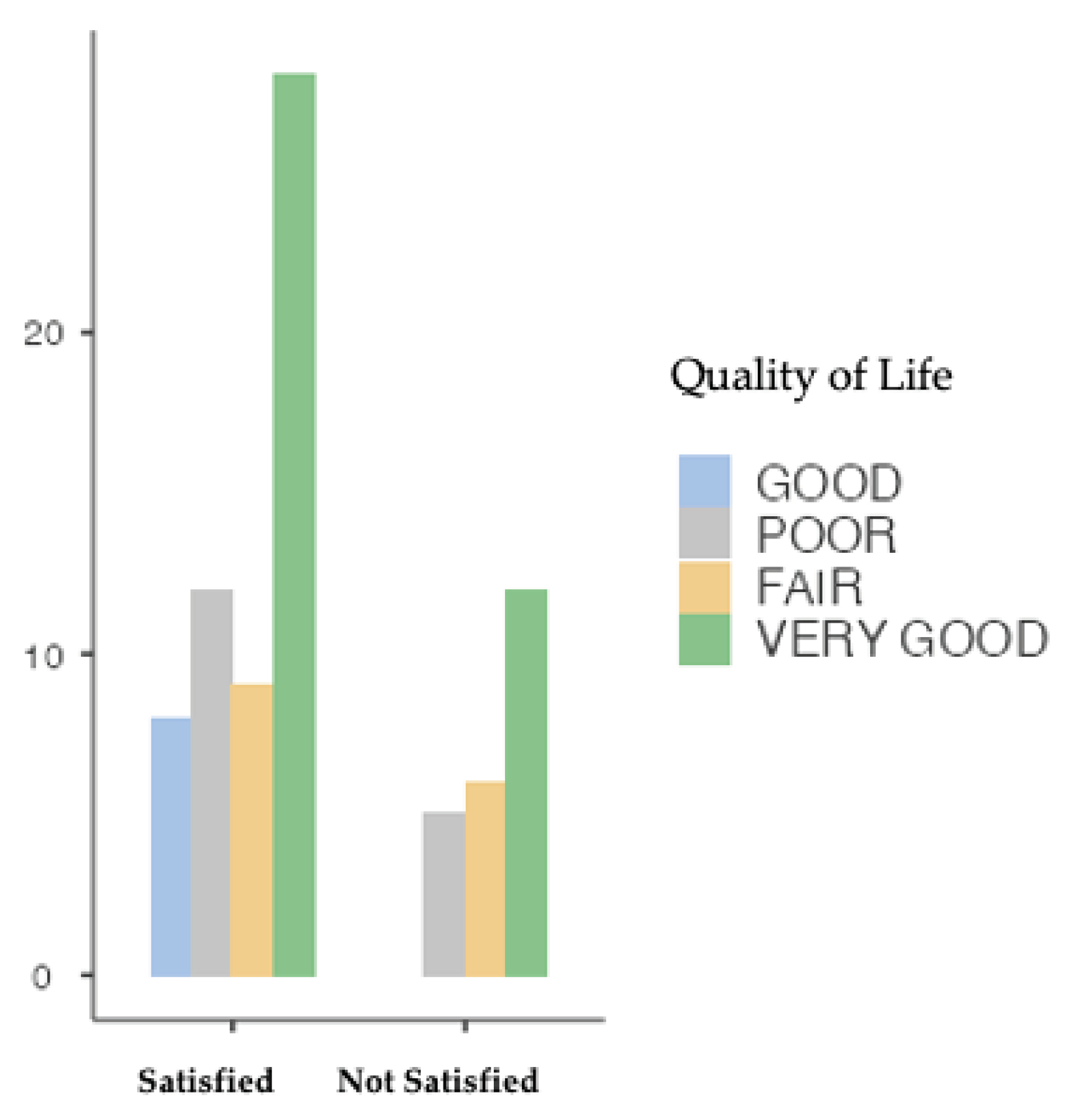

QoL’s correlation with satisfaction with telemedicine monitoring was tested, which showed that most users with higher levels of QoL were more satisfied with telemedicine (n=28). Inferential statistical analysis shows that the quality of life is independent of the level of satisfaction with telemedicine (p=0.242; X2= 4.19; Fisher=0.241) (

Figure 3).

When we specifically evaluate each metabolic risk factor, we have an initial assessment of 67 patients with hypertension, which fell to 4 after three years of surgery. With diabetes, we had 63 patients at Baseline, which reduced to 9 after three years. With dyslipidemia, we initially had 66 users taking medication to control the disease, decreasing to 5 in the third year, as with OSAS, which decreased from 14 to 2 users.

Table 4 shows the relationship between metabolic risk factors, QoL, and QoS, with p-values showing no significant differences between the levels.

Similar results are observed when we relate %PEP to QoL and QoS, with no significant results. On the other hand, the fact that they had undergone the entire follow-up via telemedicine and were satisfied or not showed a statistically significant association (p<0.001) (

Table 5) with the percentage of excess weight loss.

4. Discussion

The study aimed to analyze the impact of the use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic on the results of bariatric surgery and users’ satisfaction with this follow-up.

We wanted to evaluated if the process of managing the treatment of obesity via telemedicine in the postoperative period had a negative or positive impact on weight control and comorbidities associated with obesity, as well as on QoL and QoS.

Bariatric surgery is a weight loss procedure that allows people with severe obesity to achieve significant and sustained weight loss. However, bariatric surgery patients need ongoing care and support to maintain a healthy weight and avoid complications [

23]. eHealth, the use of electronic technologies to manage health and well-being, has emerged as a promising tool to facilitate the monitoring of users in various clinical areas, which may include bariatric surgery. It has the potential to provide several benefits, including greater user involvement and better access to care and improved communication between users and healthcare providers [

18].

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted many aspects of follow-up after bariatric surgery, including physical and mental health, weight control and eventually weight recovery. This impact was due to increased sedentary behavior and reduced levels of physical activity, which translated into an essential need for support from the post-bariatric surgery follow-up team [

24].

The pandemic has resulted in a significant shift towards telemedicine as a means of providing healthcare services, including follow-up consultations for bariatric surgery patients, with the potential for several advantages, including greater accessibility, convenience and reduced healthcare costs, as showed in more recent studies [

24,

25]. However, it needs to be clarified how bariatric surgery patients understand telemedicine as a follow-up modality and whether it adequately meets their needs. This difficulty may explain the percentage who was not satisfied with the follow-up, in this study.

Growing evidence suggests that bariatric patients are generally satisfied with the follow-up care provided through telemedicine. Telemedicine allows healthcare providers to monitor users remotely and provide timely interventions, improving outcomes and overall patient satisfaction [

18]. We validated in our study that users are generally satisfied with telemedicine follow-up.

Another study showed that patients undergoing bariatric surgery who received telemedicine monitoring reported high satisfaction with their care [

27]. In addition, it also conclude that user who received telemedicine follow-up had better weight loss results than those who received face-to-face follow-up. In our study, we also found that the quantitative results relating to bariatric surgery, namely the loss of excess weight, are in line with the results described on weight loss after bariatric surgery and with data previously published in this center, so there are no differences caused by the introduction of telemedicine and the change in the way follow-up was managed.

In another study, patients undergoing bariatric surgery who received telemedicine follow-up reported similar levels of satisfaction compared to those who received face-to-face follow-up [

25]. This study also found that telemedicine follow-up was associated with a lower rate of missed appointments, suggesting that it may be a more convenient and accessible option for users. This data was also validated by the sound levels of satisfaction obtained.

In general, the available evidence suggests that patients undergoing bariatric surgery are generally satisfied with the follow-up care provided through telemedicine [

24,

27].). It is also essential to ensure that telemedicine services are provided to maintain users’ privacy and confidentiality and that users receive adequate education and support to use the technology effectively.

The evidence suggests that telemedicine can effectively monitor patients undergoing bariatric surgery, leading to better weight loss results and patient satisfaction. This study validated this issue with significant values between %PEP and satisfaction with follow-up. Based on previous studies, satisfied users have better results associated with surgery [

24,

28].

We know that surgery is effective, but it requires long-term follow-up to ensure that the patient maintains weight loss and general health. Traditional postoperative follow-up appointments require a lot of time and resources, which can challenge the patient and healthcare professionals. Telemedicine can provide an alternative method of follow-up in bariatric surgery, which can positively impact treatment outcomes.

Evidence also shows that the success of bariatric surgery depends mainly on the patient’s ability to maintain healthy habits and behaviors in the long term. Regular follow-up appointments with healthcare professionals are crucial to monitoring progress, detecting complications, and providing ongoing support and guidance to these patients [

30].

The restrictions imposed, along with limited access to the hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic, have led to an increase in the level of anxiety, a decrease in the level of physical activity, weight gain and sleep disturbance [

29]. In this study, there were no different results in terms of weight loss, which clearly shows that the fact that they were monitored by telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect the results.

Bariatric surgery has a positive impact on sleep quality in obese individuals. Obesity is a known risk factor for sleep disorders such as OSAS and insomnia, which can result in poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness. One study showed that participants who underwent bariatric surgery significantly improved sleep quality and daytime sleepiness, as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [

7].

Another study showed that bariatric surgery significantly improved OSAS symptoms, such as daytime sleepiness and apnea-hypopnea index. This improvement in sleep quality and OSAS symptoms is probably due to the significant weight loss that usually occurs after bariatric surgery [

31].

In general, bariatric surgery is known to have a positive impact on sleep quality in obese individuals, particularly those with sleep apnea. However, it is essential to note that bariatric surgery is not a guaranteed solution to all sleep problems and that individual results may vary. In a study it was possible to verify that QS had deficient levels despite “excellent” levels of QoL and optimal %PEP. This is in line with the results already described in the literature [

7,

31].Metabolic risk factors, when present, have significant repercussions on comorbidities, particularly diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and OSAS [

33]. Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for control of comorbidities, regardless of weight gain and physical activity practice [

4,

7,

33]. Our study only included patients who had undergone gastric bypass, so we correlated the favorable resolution of comorbidities with this type of surgical procedure [

35].

Our data shows that after three years of follow-up, most patients have their comorbidities under control without any statistically significant relationship with the other variables. Several studies have also shown that the improvement in comorbidities is independent of weight loss [

7,

33,

35,

36,

37].

Obesity is a significant public health problem worldwide and can lead to numerous complications. Bariatric surgery is a widely used method for achieving significant and sustainable weight loss in individuals who cannot achieve it through conventional methods. However, the long-term success of bariatric surgery is highly dependent on adequate, patient-centered follow-up.

5. Limitation

As far as the limitations of this study are concerned, the inherent limitations of cross-sectional studies are present, namely that it is impossible to establish a cause-effect relationship. However, it is an important starting point for future research.

It is essential to highlight the difficulties inherent in telephone contacts.

On the other hand, other motivational variables could have been assessed, such as the barriers and facilitators to accessing health care and hospitals in the Alentejo region and the motivational profile during this post-surgical process. In this sense, controlling and differentiating these variables in future studies could be interesting.

6. Conclusions

Bariatric surgery is a form of weight loss treatment for those with severe obesity. However, follow-up care is crucial to ensure the success and safety of the procedure. ehealth technologies can play a significant role in post-bariatric surgery follow-up.

Telemedicine allows healthcare providers to monitor patients remotely via videoconferencing, messaging and other digital means. This technology can save time and resources for both users and caregivers, while ensuring effective follow-up.

In conclusion, eHealth technologies can be very useful for post-bariatric surgery follow-up.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M. and M.C.; methodology C.M. and M.C.; software, C.M. and M.C.; validation, C.M., M.C. AR and O.Z.; formal analysis, C.M. and M.C.; investigation, C.M. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M., M.C. AR and O.Z.; writing—review and editing, O.Z and AR.; supervision, O.Z. and AR; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IThe study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital do Espírito Santo de Évora (protocol code 010/23 on 31/01/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the quality of mixed methods studies in health services research (GRAMMS) for mixed methods studies in health services research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Perez-Campos, E.; Mayoral, L.P.-C.; Andrade, G.M.; Mayoral, E.P.-C.; Huerta, T.H.; Canseco, S.P.; Canales, F.J.R.; Cabrera-Fuentes, H.A.; Cruz, M.M.; Santiago, A.D.P.; et al. Obesity subtypes, related biomarkers & heterogeneity. Indian J. Med Res. 2020, 151, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Youdim, A.; Jones, D.B.; Garvey, W.T.; Hurley, D.L.; McMahon, M.M.; Heinberg, L.J.; Kushner, R.; Adams, T.D.; Shikora, S.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient—2013 Update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2013, 9, 159–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruby, A.; Manson, J.E.; Qi, L.; Malik, V.S.; Rimm, E.B.; Sun, Q.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Determinants and Consequences of Obesity. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1656–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozier, M.D.; Ghaferi, A.A.; Rose, A.; Simon, N.-J.; Birkmeyer, N.; Prosser, L.A. Patient Preferences for Bariatric Surgery: Findings From a Survey Using Discrete Choice Experiment Methodology. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, e184375–e184375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaniolas, K.; Kasten, K.R.; Celio, A.; Burruss, M.B.; Pories, W.J. Postoperative Follow-up After Bariatric Surgery: Effect on Weight Loss. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 900–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Apovian, C.; Brethauer, S.; Garvey, W.T.; Joffe, A.M.; Kim, J.; Kushner, R.F.; Lindquist, R.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; Seger, J.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures – 2019 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 16, 175–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Carvalho, M.; Oliveira, L.; Palmeira, A.; Rodrigues, L.M.; Gregório, J. The Long-Term Association between Physical Activity and Weight Regain, Metabolic Risk Factors, Quality of Life and Sleep after Bariatric Surgery. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, M.; Näslund, I.; Rask, E.; Karlsson, J.; Sundbom, M.; Edholm, D.; Karlsson, F.A.; Svensson, F.; Szabo, E. Health-Related Quality-of-Life (HRQoL) on an Average of 12 Years After Gastric Bypass Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2015, 25, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, N.; Bower, P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwame, A.; Petrucka, P.M. A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camolas, J.; Santos, O.; Moreira, P.; Carmo, I.D. INDIVIDUO: Results from a patient-centered lifestyle intervention for obesity surgery candidates. Obes. Res. Clin. Pr. 2017, 11, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretti, G.; Marinari, G.M.; Vanni, E.; Ferrari, C. Value-Based Healthcare and Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Implementation in a High-Volume Bariatric Center in Italy. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 2519–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastenau, J.; Kolotkin, R.L.; Fujioka, K.; Alba, M.; Canovatchel, W.; Traina, S. A call to action to inform patient-centred approaches to obesity management: Development of a disease-illness model. Clin. Obes. 2019, 9, e12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Faxvaag, A.; Svanæs, D. The Impact of an eHealth Portal on Health Care Professionals’ Interaction with Patients: Qualitative Study. J. Med Internet Res. 2015, 17, e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Mutsekwa, R.N.; Hamilton, K.; Campbell, K.L.; Kelly, J. Are eHealth interventions for adults who are scheduled for or have undergone bariatric surgery as effective as usual care? A systematic review. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2021, 17, 2065–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangieri, C.W.; Johnson, R.J.; Sweeney, L.B.; Choi, Y.U.; Wood, J.C. Mobile health applications enhance weight loss efficacy following bariatric surgery. Obes. Res. Clin. Pr. 2019, 13, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newell, S.; Jordan, Z. The patient experience of patient-centered communication with nurses in the hospital setting: a qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Évid. Synth. 2015, 13, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. André and P. Ribeiro, “E-health: as TIC como mecanismo de evolução em saúde,” Gestão e Desenvolvimento, vol. 28, no. 28, pp. 95–116, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- de Queiroz, C.; Sallet, J.A.; Silva, P.G.M.D.B.E.; Queiroz, L.d.G.P.d.S.; Pimentel, J.A.; Sallet, P.C. Application of BAROS’ questionnaire in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery with 2 years of evolution. Arq. de Gastroenterol. 2017, 54, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, J.; Infante, P.; Ribeiro, S.; Ferreira, A.; Silva, A.C.; Caravana, J.; Carvalho, M.G. Translation, Adaptation and Validation of a Portuguese Version of the Moorehead-Ardelt Quality of Life Questionnaire II. Obes. Surg. 2014, 24, 1940–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João, K.A.D.R.; Becker, N.B.; Jesus, S.d.N.; Martins, R.I.S. Validation of the Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-PT). Psychiatry Res. 2017, 247, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecasis, F.; Interna, H.G.d.O.S.d.M. Consulta Telefónica em Contexto Pandémico: Avaliação da Satisfação dos Doentes. Med. Interna 2021, 28, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassil, F.C.; Richards, R.; Carnemolla, A.; Lewis, N.; Montagut-Pino, G.; Kingett, H.; Doyle, J.; Kirk, A.; Brown, A.; Chaiyasoot, K.; et al. Patients' views and experiences of live supervised tele-exercise classes following bariatric surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: The BARI-LIFESTYLE qualitative study. Clin. Obes. 2021, 12, e12499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockalingam, S.; Leung, S.E.; Ma, C.; Hawa, R.; Wnuk, S.; Dash, S.; Jackson, T.; Cassin, S.E. The Impact of Telephone-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Mental Health Distress and Disordered Eating Among Bariatric Surgery Patients During COVID-19: Preliminary Results from a Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 1884–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.D.; Rajaratnam, T.; Stall, B.; Hawa, R.; Sockalingam, S. Exploring the Effects of Telemedicine on Bariatric Surgery Follow-up: a Matched Case Control Study. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 2704–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillot, A.; Boissy, P.; Tousignant, M.; Langlois, M.-F. Feasibility and effect of in-home physical exercise training delivered via telehealth before bariatric surgery. J. Telemed. Telecare 2016, 23, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runfola, M.; Fantola, G.; Pintus, S.; Iafrancesco, M.; Moroni, R. Telemedicine Implementation on a Bariatric Outpatient Clinic During COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy: an Unexpected Hill-Start. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 5145–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, D.M.; Lehman, L.; Quinlin, R.; Zullo, T.; Hoffman, L. Effect of Patient-Centered Care on Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Care. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2008, 23, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, K.E.; Philip, J.; Billmeier, S.E.; Trus, T.L. The effects of using telemedicine for introductory bariatric surgery seminars during the COVID-19 pandemic. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 37, 5509–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güven, B.; Akyolcu, N. Effects of Nurse-Led Education on Quality of Life and Weight Loss in Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery. Bariatr. Surg. Pr. Patient Care 2020, 15, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkhosh, K.; Switzer, N.J.; El-Hadi, M.; Birch, D.W.; Shi, X.; Karmali, S. The Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review. Obes. Surg. 2013, 23, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.F.; de Bruin, P.F.C.; de Bruin, V.M.S.; Lopes, P.M.; Lemos, F.N. Obesity, Hypersomnolence, and Quality of Sleep: the Impact of Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baillot, A.; Romain, A.J.; Boisvert-Vigneault, K.; Audet, M.; Baillargeon, J.P.; Dionne, I.J.; Valiquette, L.; Chakra, C.N.A.; Avignon, A.; Langlois, M.-F. Effects of Lifestyle Interventions That Include a Physical Activity Component in Class II and III Obese Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0119017–e0119017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, C.A. Asociación a largo plazo entre la actividad física, el aumento de peso, los factores de riesgo metabólicos y la calidad de vida en pacientes sometidos a cirugía bariátrica – Revisión de la literatura sistemática (Long-term association between physical activity, weight gain, metabolic risk factors and quality of life in patients undergoing bariatric surgery - Systematic Literature Review) (Associação no longo-termo entre a prática de atividade física, o reganho de peso, fatores de risco metabólic. Retos 2022, 46, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol-Rafols, J.; Al Abbas, A.I.; Devriendt, S.; Guerra, A.; Herrera, M.F.; Himpens, J.; Pardina, E.; Pouwels, S.; Ramos, A.; Ribeiro, R.J.; et al. Conversion of Adjustable Gastric Banding to Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass in One or Two Steps: What Is the Best Approach? Analysis of a Multicenter Database Concerning 832 Patients. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 5026–5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, F.; Nathan, D.M.; Eckel, R.H.; Schauer, P.R.; Alberti, K.G.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Del Prato, S.; Ji, L.; Sadikot, S.M.; Herman, W.H.; et al. Metabolic Surgery in the Treatment Algorithm for Type 2 Diabetes: A Joint Statement by International Diabetes Organizations. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016, 12, 1144–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, F.; Gagner, M. Potential of Surgery for Curing Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Ann. Surg. 2002, 236, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, C.; Carvalho, M.; Oliveira, L.; Rodrigues, L.M.; Gregório, J. Nurse-led intervention for the management of bariatric surgery patients: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).