Submitted:

25 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

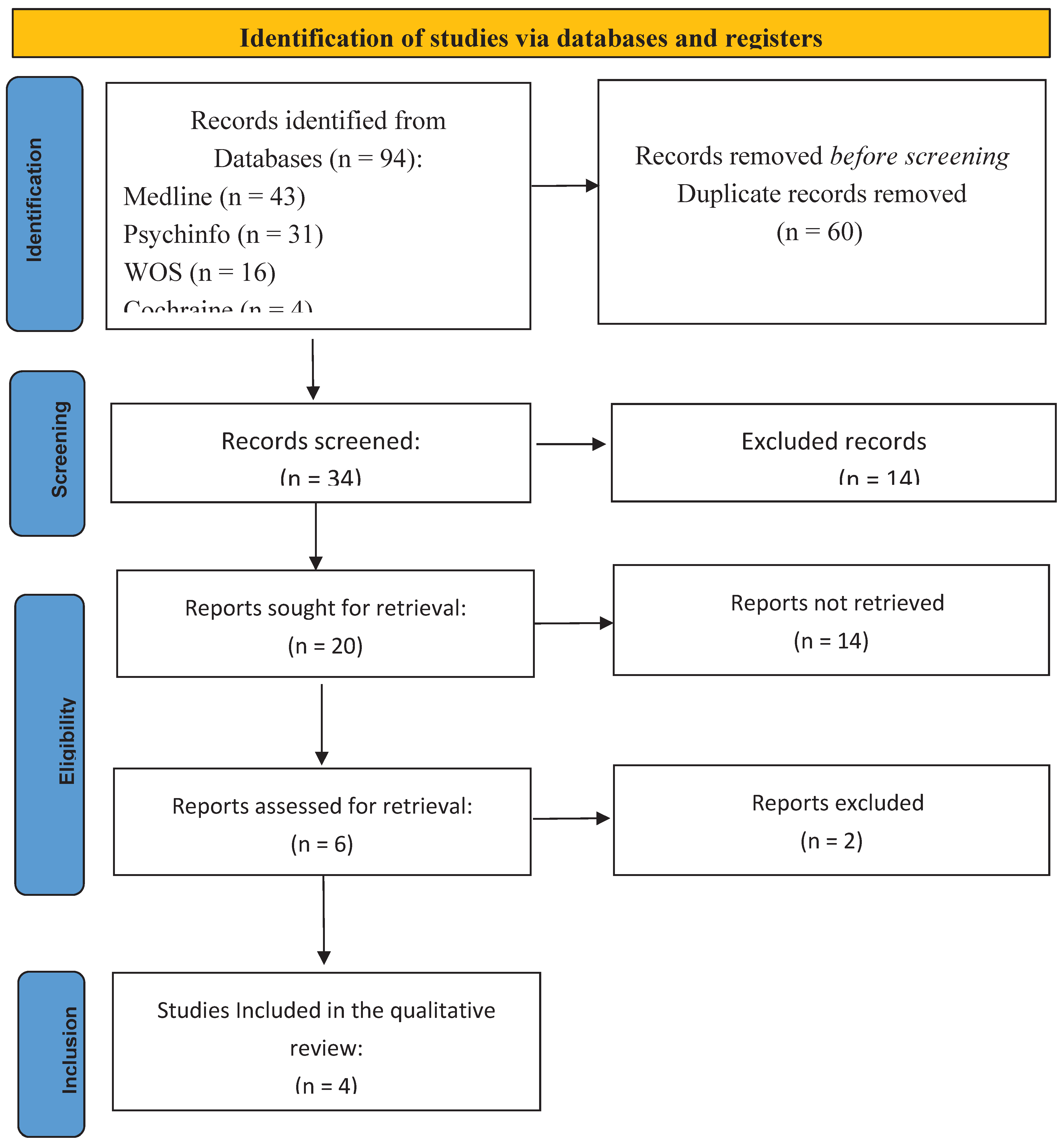

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Case Report

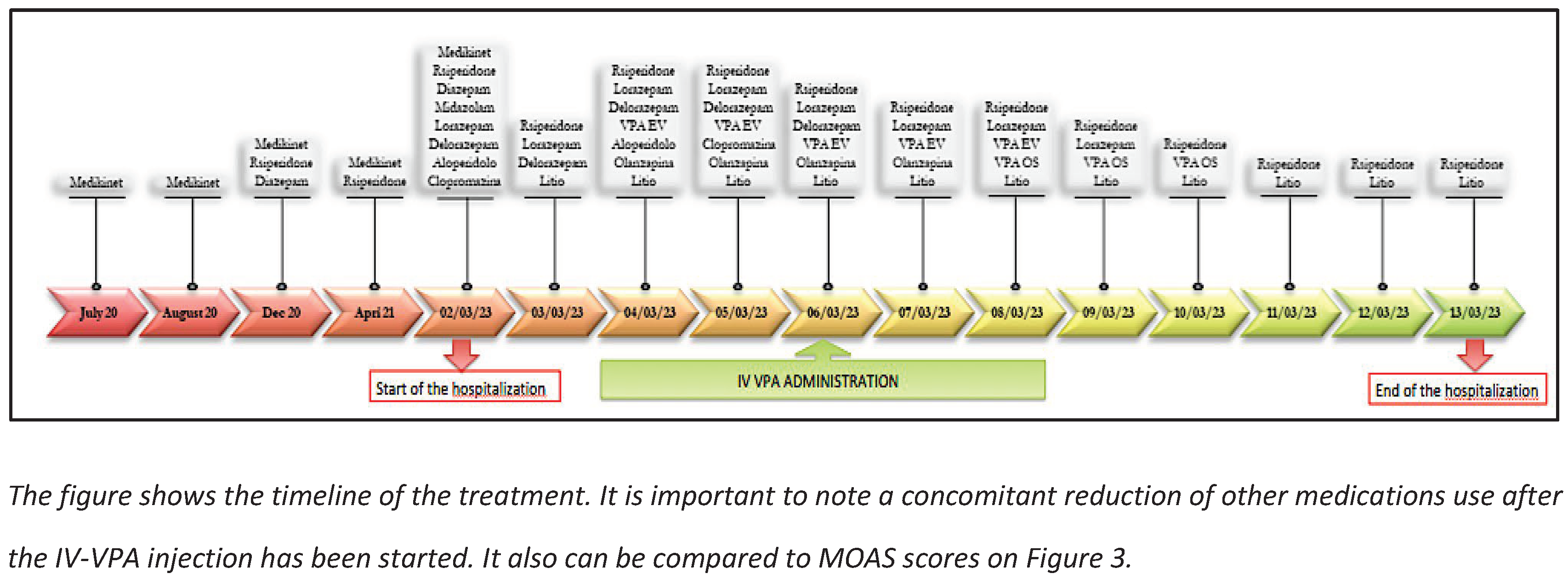

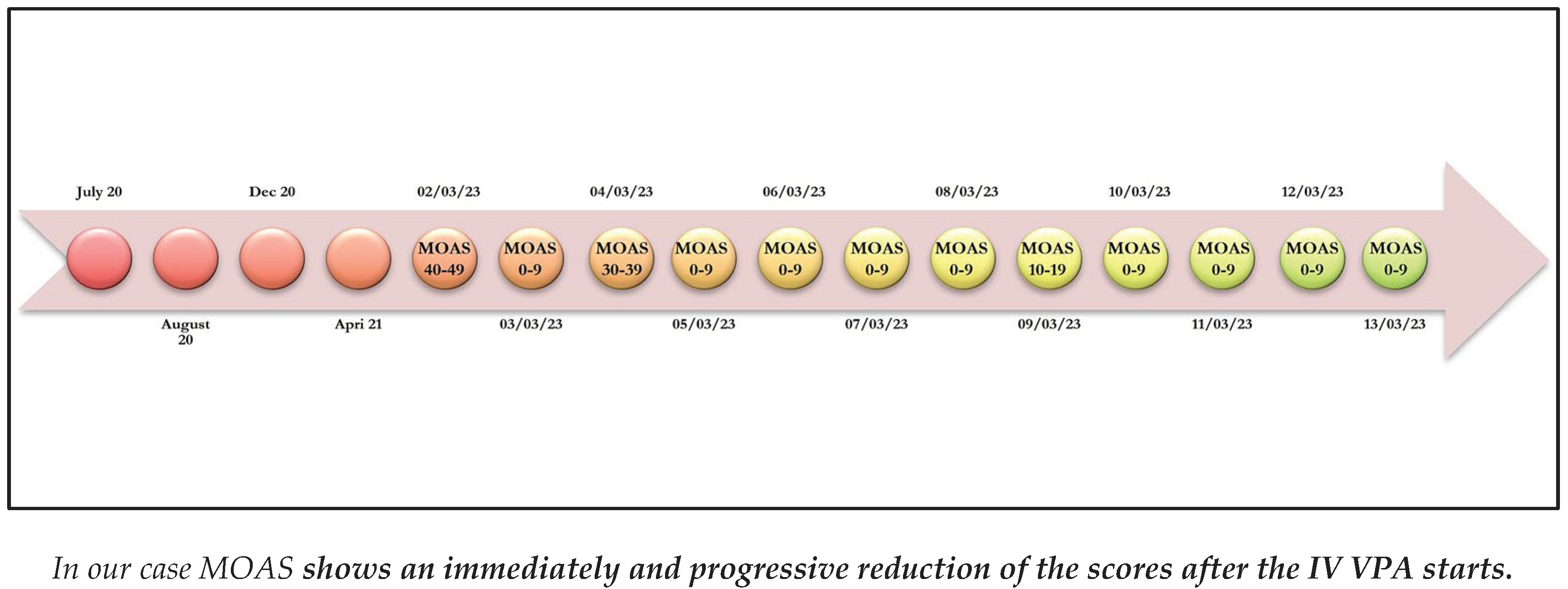

3. Case Report

Emergency Acceptance

4. Results of Literature Review

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Luzio, M.; Guerrera, S.; Pontillo, M.; Lala, M.R.; Casula, L.; Valeri, G.; Vicari, S. Autism spectrum disorder, very-early onset schizophrenia, and child disintegrative disorder: the challenge of diagnosis. A case-report study. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1212687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aishworiya, R.; Valica, T.; Hagerman, R.; Restrepo, B. An Update on Psychopharmacological Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persico, A.M.; Ricciardello, A.; Lamberti, M.; Turriziani, L.; Cucinotta, F.; Brogna, C.; Vitiello, B.; Arango, C. The pediatric psychopharmacology of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review - Part I: The past and the present. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 110, 110326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechler, K.; Banaschewski, T.; Hohmann, S.; Häge, A. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment options for ADHD in children and adolescents. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 230, 107940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carucci, S.; Balia, C.; Gagliano, A.; Lampis, A.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Danckaerts, M.; Dittmann, R.W.; Garas, P.; Hollis, C.; Inglis, S.; et al. Long term methylphenidate exposure and growth in children and adolescents with ADHD. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 120, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, K.K.C.; Häge, A.; Banaschewski, T.; Inglis, S.K.; Buitelaar, J.; Carucci, S.; Danckaerts, M.; Dittmann, R.W.; Falissard, B.; Garas, P.; et al. Long-term safety of methylphenidate in children and adolescents with ADHD: 2-year outcomes of the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Drugs Use Chronic Effects (ADDUCE) study. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, A.; Fucà, E.; Guerrera, S.; Napoli, E.; Valeri, G.; Vicari, S. Characterization of Clinical Manifestations in the Co-occurring Phenotype of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzullo, L.R. Pharmacologic Management of the Agitated Child. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2014, 30, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, M.; Weltens, I.; Bervoets, C.; De Fruyt, J.; Samochowiec, J.; Fiorillo, A.; Sampogna, G.; Bienkowski, P.; Preuss, W.U.; Misiak, B.; et al. The pharmacological management of agitated and aggressive behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 57, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, R.; Malas, N.; Feuer, V.; Silver, G.H.; Prasad, R.; Mroczkowski, M.M.; Pena-Nowak, M.; Gaveras, G.; Goepfert, E.; Hartselle, S.; et al. Best Practices for Evaluation and Treatment of Agitated Children and Adolescents (BETA) in the Emergency Department: Consensus Statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry. WestJEM 21.2 March Issue 2019, 20, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janković, S.M.; Janković, S.V. Lessons learned from the discovery of sodium valproate and what has this meant to future drug discovery efforts? Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2020, 15, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhu, X. Combined effects of levetiracetam and sodium valproate on paediatric patients with epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Seizure 2021, 95, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevitt, S.J.; Sudell, M.; Cividini, S.; Marson, A.G.; Smith, C.T. Antiepileptic drug monotherapy for epilepsy: a network meta-analysis of individual participant data. Emergencias 2022, 2022, CD011412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamiri, R.A.; Ghaempanah, M.; Khosroshahi, N.; Nikkhah, A.; Bavarian, B.; Ashrafi, M.R. Efficacy and safety of intravenous sodium valproate versus phenobarbital in controlling convulsive status epilepticus and acute prolonged convulsive seizures in children: A randomised trial. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2012, 16, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridle, C.; Palmer, S.; Bagnall, A.-M.; Darba, J.; Duffy, S.; Sculpher, M.; Riemsma, R. A rapid and systematic review and economic evaluation of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of newer drugs for treatment of mania associated with bipolar affective disorder. Heal. Technol. Assess. 2004, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, C.S.; Vázquez, G.H.; Hawken, E.R.; Biorac, A.B.; Tondo, L.M.; Baldessarini, R.J. Long-Term Treatment of Bipolar Disorder with Valproate: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analyses. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A.; Reid, K.; Young, A.H.; Macritchie, K.; Geddes, J. Valproic acid, valproate and divalproex in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Emergencias 2013, 2013, CD003196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellings, J.A.; Weckbaugh, M.; Nickel, E.J.; Cain, S.E.; Zarcone, J.R.; Reese, R.M.; Hall, S.; Ermer, D.J.; Tsai, L.Y.; Schroeder, S.R.; et al. ADouble-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Valproate for Aggression in Youth with Pervasive Developmental Disorders. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 15, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollander, E.; Chaplin, W.; Soorya, L.; Wasserman, S.; Novotny, S.; Rusoff, J.; Feirsen, N.; Pepa, L.; Anagnostou, E. Divalproex Sodium vs Placebo for the Treatment of Irritability in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 35, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, E.; Soorya, L.; Wasserman, S.; Esposito, K.; Chaplin, W.; Anagnostou, E. Divalproex sodium vs. placebo in the treatment of repetitive behaviours in autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005, 9, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivola, M.; Civardi, S.; Damiani, S.; Cipriani, N.; Silva, A.; Donadeo, A.; Politi, P.; Brondino, N. Effectiveness and safety of intravenous valproate in agitation: a systematic review. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 239, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripodi, B.; Matarese, I.; Carbone, M.G. A Critical Review of the Psychomotor Agitation Treatment in Youth. Life 2023, 13, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Swanson, W. J. Swanson, W. Nolan e W. Pelham, «The SNAP rating scale for the diagnosis of attention deficit disorder,» in Meeting of the American Psychological Association, Los Angeles, 1981.

- M. Nobile, B. M. Nobile, B. Alberti e A. Zuddas, CRS-R. Conners’ Rating Scales. Revised. Manuale, Firenze: Giunti Editore, 2007.

- T. M. Achenbach, «The Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments,» The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment, pp. 429-466, 1999.

- H. GaleRoid, L. J. H. GaleRoid, L. J. Miller, M. Pomplun e C. Koch, Leiter International Performance Scale – Third Edition, 2016.

- C. Lord, M. C. Lord, M. Rutter, P. C. DiLavore, S. Risi, R. J. Luyster, K. Gotham, S. L. Bishop e W. Guthrie, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition, Western Psychological Services, 2012.

- Kay, S.R.; Wolkenfeld, F.; Murrill, L.M. Profiles of Aggression among Psychiatric Patients. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1988, 176, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadollahi, S.; Heidari, K.; Hatamabadi, H.; Vafaee, R.; Yunesian, S.; Azadbakht, A.; Mirmohseni, L. Efficacy and safety of valproic acid versus haloperidol in patients with acute agitation. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 30, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, G.; Gaudreau, P.-O.M.; Leblanc, N.B. Efficacy of Topiramate, Valproate, and Their Combination on Aggression/Agitation Behavior in Patients With Psychosis. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 26, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.; Fountoulakis, K.; Siamouli, M.; Gonda, X.; Vieta, E. Is Anticonvulsant Treatment of Mania a Class Effect? Data from Randomized Clinical Trials. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2009, 17, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, P.-T.; Chen, Y.-W.; Chung, W.; Tu, K.-Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Wu, C.-K.; Lin, P.-Y. Significant Effect of Valproate Augmentation Therapy in Patients With Schizophrenia. Medicine 2016, 95, e2475–e2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, G.; Albert, U.; Salvi, V.; Mancini, M.; Bogetto, F. Valproate or olanzapine add-on to lithium: An 8-week, randomized, open-label study in Italian patients with a manic relapse. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 99, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, J.W.; Quarles, E.; Pharm. D., E.Q. Intravenous Valproate in Neuropsychiatry. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2000, 20, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Weiser, K.; Vergel, Y.B.; Beynon, S.; Dunn, G.; Barbieri, M.; Duffy, S.; Geddes, J.; Gilbody, S.; Palmer, S.; Woolacott, N. A systematic review and economic model of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions for preventing relapse in people with bipolar disorder. Heal. Technol. Assess. 2007, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengappa, K.; Chalasani, L.; Brar, J.S.; Parepally, H.; Houck, P.; Levine, J. Changes in body weight and body mass index among psychiatric patients receiving lithium, valproate, or topiramate: An open-label, nonrandomized chart review. Clin. Ther. 2002, 24, 1576–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVane, C.L. Pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and tolerability of valproate. . 2003, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Adamou, M.; Puchalska, S.; Plummer, W.; Hale, A.S. Valproate in the treatment of PTSD: systematic review and meta analysis. Curr. Med Res. Opin. 2007, 23, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, D.J.; Fontaine, G.V.; Smith, K.E.; Riker, R.R.; Miller, R.R.; Lerwick, P.A.; Lucas, F.; Dziodzio, J.T.; Sihler, K.C.; Fraser, G.L. Valproate for agitation in critically ill patients: A retrospective study. J. Crit. Care 2017, 37, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basan e, S. Leucht, «Valproate for schizophrenia,» The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, vol. 1; 2004; [CrossRef]

- Guay, D.R. The Emerging Role of Valproate in Bipolar Disorder and Other Psychiatric Disorders. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 1995, 15, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, C.; Averna, R.; Labonia, M.P.; Riccioni, A.; Vicari, S. Intravenous Valproic Acid Add-On Therapy in Acute Agitation Adolescents With Suspected Substance Abuse: A Report of Six Cases. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 41, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, E.; Mandolini, G.; Delvecchio, G.; Bressi, C.; Soares, J.; Brambilla, P. Intravenous valproate in the treatment of acute manic episode in bipolar disorder: A review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-S.; Zhang, L.-L.; Lin, Y.-Z.; Guo, Q. Sodium valproate for the treatment of Tourette׳s syndrome in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 226, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Schwarz, A. C. Schwarz, A. Volz, C. Li e S. Leucht, «Valproate for schizophrenia.,» The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, vol. 3; 2008; [CrossRef]

- Fenn, H.H.; Sommer, B.R.; A Ketter, T.; Alldredge, B. Safety and tolerability of mood-stabilising anticonvulsants in the elderly. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2006, 5, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yagoda, S.; Yao, B.; Graham, C.; von Moltke, L. Combination of Olanzapine and Samidorphan Has No Clinically Significant Effect on the Pharmacokinetics of Lithium or Valproate. Clin. Drug Investig. 2019, 40, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Oerlinghausen, B.; Retzow, A.; Henn, F.A.; Giedke, H.; Walden, J. Valproate as an Adjunct to Neuroleptic Medication for the Treatment of Acute Episodes of Mania: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2000, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siriwardena, S.; McAllister, N.; Islam, S.; Craig, J.; Kinney, M. The emerging story of Sodium Valproate in British newspapers- A qualitative analysis of newspaper reporting. Seizure 2022, 101, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois, J.A.; Koike, A.K.; Simmons, J.E.; Telles, S.; Eggleston, C. Adjunctive Valproic Acid for Delirium and/or Agitation on a Consultation-Liaison Service: A Report of Six Cases. J. Neuropsychiatry 2005, 17, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilty, D.M.; Rodriguez, G.D.; Hales, R.E. Intravenous Valproate for Rapid Stabilization of Agitation in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. J. Neuropsychiatry 1998, 10, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, Y.; Cramer, A.C.M.; Ament, A.; Lolak, S.; Maldonado, J.R. Valproic Acid for Treatment of Hyperactive or Mixed Delirium: Rationale and Literature Review. Psychosomatics 2015, 56, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, J.; Helfer, B.; Li, C.; Leucht, S. Valproate for schizophrenia. Emergencias 2016, 2016, CD004028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aman, M.G.; Singh, N.N.; Stewart, A.W.; Field, C.J. The aberrant behavior checklist: a behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. . 1985, 89, 485–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- W. O. Faustman e E. Overall J, «Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale,» The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment, pp. 791-830, 1999.

- Bech, P. The Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale in Clinical Trials of Therapies for Bipolar Disorder. CNS Drugs 2002, 16, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagadheesan, K.; Duggal, H.S.; Gupta, S.C.; Basu, S.; Ranjan, S.; Sandil, R.; Akhtar, S.; Nizamie, S.H. Acute Antimanic Efficacy and Safety of Intravenous Valproate Loading Therapy: An Open-Label Study. Neuropsychobiology 2003, 47, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, E.L.; Chui, H.C. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. . 1987, 48, 314–8. [Google Scholar]

- J. M. Silver e S. C. Yudofsky, «The Overt Ag- gression Scale: overview and guiding principles,» J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neu- rosci, 1991.

- Young, R.C.; Biggs, J.T.; Ziegler, V.E.; Meyer, D.A. A Rating Scale for Mania: Reliability, Validity and Sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry 1978, 133, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Exams (blood levels) |

Range | 02/03/23 | 04/03/23 | 06/03/23 | 08/03/23 | 10/03/23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium |

0.6-1.2 mEq/L |

* | * | * | 0.35 | 0.53 |

| Ammonia |

19-54 μg/mL |

46 | * | 73 | 97 | 96 |

| VPA |

50-100 μg/mL |

* | * | 92.7 | 83.4 | 63.8 |

| PRL |

3.2-13.5 ng/mL |

* | 16.9 | * | 41.38 | 43.01 |

| AST |

<34 U/L |

58 | 42 | 32 | 27 | 27 |

| ALT |

10-49 U/L |

34 | 29 | 24 | 16 | 16 |

| LDH |

120-246 U/L |

433 | 401 | 367 | 280 | 277 |

| GGT |

<73 U/L |

18 | * | 19 | 17 | 18 |

| TBIL |

0.3-1.2 mg/dL |

0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Cr |

0.6-1.1 mg/dL |

0.69 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.71 |

| ECG | Range | 02/03/23 | 04/03/23 | 06/03/23 | 08/03/23 | 10/03/23 |

| QTC | < 440 msec | 422 | 406 | 439 | 395 | 397 |

| LEGEND: * not evaluated; VPA= valproic acid; PRL= prolactin; AST= aspartate transaminase; ALT= alanine aminotransferase; LDH= lactate dehydrogenase; GGT= gamma-glutamyl transferase; TBIL= total bilirubine; Cr= creatinine; QTc= correct QT interval | ||||||

| Title | Author (s) | Study | Previous Diagnosis | Age | Administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Effectiveness and safety of intravenous valproate in agitation: a systematic review. | Olivola et al. (2022) [21] | SR | AD;ADHD; ASD; BD; CD; MD; MDD; ODD; PSY; PTSD; SA; Schizoph. | C; Ado; Adu | IV |

| 2. Efficacy and safety of valproic acid versus haloperidol in patients with acute agitation: results of a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. | Asadollahi et al. (2015) [29] | RCT | AJ; MD; PSY | Adu | IV |

| 3. Efficacy of topiramate, valproate, and their combination on aggression/agitation behavior in patients with psychosis. | Gobbi G. et al. (2006) [30] | CCS | BD; SAD; Schizoph. | Adu | O |

| 4. Is anticonvulsant treatment of mania a class effect? Data from randomized clinical trials. | Rosa AR et al. (2011) [31] | SR | Mania | NA | O |

| 5. Significant Effect of Valproate Augmentation Therapy in Patients With Schizophrenia: A Meta-analysis Study. | Tseng PT et al. (2016) [32] | MA | SAD; Schizoph. | NA | O |

| 6. Valproate or olanzapine add-on to lithium: an 8-week, randomized, open-label study in Italian patients with a manic relapse. | Maina G et al. (2007) [33] | RCT | BD | Adu | O |

| 7. Intravenous valproate in neuropsychiatry | Norton JW & Quarles E. (2000) [34] | SR | BD; Mania | Adu | IV |

| 8. Lessons learned from the discovery of sodium valproate and what has this meant to future drug discovery efforts? | Janković SM & Janković SV. (2020) [11] | R | BD | C; Ado | O |

| 9. A rapid and systematic review and economic evaluation of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of newer drugs for treatment of mania associated with bipolar affective disorder. | Bridle C et al. (2004) [15] | R | BD | C; Ado; Adu | O |

| 10. Long-Term Treatment of Bipolar Disorder with Valproate: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analyses. | Yee CS et al. (2021) [16] | R; MA | BD | Adu | O |

| 11. A systematic review and economic model of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions for preventing relapse in people with bipolar disorder. | Soares-Weiser K et al. (2007) [35] | SR | BD | Adu | O |

| 12. Changes in body weight and body mass index among psychiatric patients receiving lithium, valproate, or topiramate: an open-label, nonrandomized chart review | Chengappa KN et al. (2002) [36] | R | BD; SA; SAD; MDD; Schizoph. | NA | NA |

| 13. Pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and tolerability of valproate. | DeVane CL (2003) [37] | R | BD | C; Ado; Adu | O |

| 14. Valproate in the treatment of PTSD: systematic review and meta analysis. | Adamou M et al. (2007) [38] | SR, MA | PTSD | Adu | O |

| 15. Valproate for agitation in critically ill patients: A retrospective study. | Gagnon DJ et al. (2017) [39] | RS | AD; ADHD; BD; MDD; PTSD | Adu | O |

| 16. Valproate as an adjunct to antipsychotics for schizophrenia: a systematic review of randomized trials. | Basan A et al. (2004) [40] | SR | SAD; Schizoph. | NA | O |

| 17. The emerging role of valproate in bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders. | Guay DR (1995) [41] | R | BD; SAD | C; Ado; Adu | O |

| 18. Intravenous Valproic Acid Add-On Therapy in Acute Agitation Adolescents With Suspected Substance Abuse: A Report of Six Cases. | Battaglia C et al. (2018) [42] | CR | CD; MD; ODD; PSY; SA | Ado | IV |

| 19. Intravenous valproate in the treatment of acute manic episode in bipolar disorder: A review. | Fontana E (2019) [43] | R | BD | C; Ado; Adu | IV |

| 20. Sodium valproate for the treatment of Tourette׳s syndrome in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. | Yang CS et al. (2015) [44] | SR, MA | TS | C; Ado | O |

| 21. Valproate for schizophrenia. | Schwarz C et al. (2008) [45] | R | PSY; Schizoph. | Adu | O |

| 22. Safety and tolerability of mood-stabilising anticonvulsants in the elderly. | Fenn HH et al. (2006) [46] | R | MD | Adu | O |

| 23. Combination of Olanzapine and Samidorphan Has No Clinically Significant Effect on the Pharmacokinetics of Lithium or Valproate. | Sun L et al. (2019) [47] | CS | BD | Adu | O |

| 24. Valproic acid, valproate and divalproex in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. | Cipriani A et al. (2013) [17] | R | BD | C; Ado; Adu | O |

| 25. Valproate as an adjunct to neuroleptic medication for the treatment of acute episodes of mania: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. European Valproate Mania Study Group. | Müller-Oerlinghausen B et al. (2000) [48] | CT | Mania | Adu | O |

| 26. The emerging story of Sodium Valproate in British newspapers- A qualitative analysis of newspaper reporting. | Siriwardena S et al. (2022) [49] | TA | SAD | C; Ado; Adu | NA |

| 27. Adjunctive valproic acid for delirium and/or agitation on a consultation-liaison service: a report of six cases | Bourgeois JA et al. (2005) [50] | CR | A, BD,PTSD, Schizoph. | Adu | IV |

| 28. Intravenous valproate for rapid stabilization of agitation in neuropsychiatric disorders | Hilty DM et al. (1998) [51] | CR | ASD | C | IV |

| 29. Valproic acid for treatment of hyperactive or mixed delirium: rationale and literature review | Sher Y et al. (2015) [52] | R | Delirium | Ado; Adu | IV |

| 30. A Critical Review of the Psychomotor Agitation Treatment in Youth | Tripodi B et al. (2023) [22] | R | AD;ADHD; ASD; BD; CD; MD; ODD; PSY; PTSD, SA | C; Ado; Adu | IV |

| 31. A double-blinde, placebo-controlled study of valproate for aggression in youth with pervasive developmental disorders | Hellings J.A. et al. (2005) [18] | RCT | ASD | C; Ado; Adu | O |

| 32. Divalproex sodium vs. placebo in the treatment of repetitive behaviours in autism spectrum disorder | Hollander E. et al. (2005) [20] | CT | ASD | C; Ado; Adu | O |

| 33. Divalproex sodium vs. placebo in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescent with autism spectrum disorder | Hollander E. et al. (2010) [19] | CT | ASD | C; Ado | O |

| 34. Valproate for schizophrenia (Review) | Wang J et al. (2016) [53] | R | SAD; Schizoph. | Adu | NA |

| Study | Study design | Diagnosis | Administration | Dosage/phases | Period of treatment | Concomitant medication | Outcomes | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intravenous Valproic Acid Add-On Therapy in Acute Agitation Adolescents With Suspected Substance Abuse: A Report of Six Cases. (Battaglia C et al. 2018) [42] | Case report | CD; MD; ODD; PSY; SA | IV | 1200-1800 mg/day | 5-17 days | SGAs MS BDZ |

MOAS BPRS |

1 |

| 2. Intravenous valproate in the treatment of acute manic episode in bipolar disorder: A review (Fontana E 2019) [43] | Review | BD | IV |

|

3 days 15 days |

|

BRMAS YMRS CGI-S MMSE |

1 |

| 3. Intravenous valproate for rapid stabilization of agitation in neuropsychiatric disorders ( Hilty DM et al. 1998) [51] | Case report | ASD | IV O |

Loading fase- 2000 mg/day(40 mg/kg) Maintenance dose 1000 mg/day |

10’ 6 months |

SGAs, ACH | OAS | 1 |

| 4. A Critical Review of the Psychomotor Agitation Treatment in Youth ( Tripodi B et al. 2023) [22] | Review | ASD; CD; MD; ODD; PSY; SA |

|

|

|

NA | / | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).