1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship plays a key role in the social, economic, and cultural development of the country, as it reduces unemployment and drives technological progress by promoting innovation and wealth [

1,

2,

3]. In this context, entrepreneurship is defined as the “creation of an economic activity that focuses on novelty, systemic thinking, and proactivity” [

2] (p. 19). However, the covid-19 pandemic affected the global economy, with impacts on entrepreneurship and working conditions. Accordingly, Ratten [

4] observes that, despite the barriers and challenges, many entrepreneurs managed to innovate and turn the crisis into an opportunity for their businesses. Cazeri et al. [

5] add that the crisis generated by the covid-19 pandemic provided new business opportunities, and thus alternative ways of working and new profile of worker competence.

In this sense, Hernández-Sánches et al. [

1] point out that entrepreneurship depends on developing and optimizing entrepreneurs’ competencies to promote innovation and productivity. Therefore, more and more studies in this area of knowledge [

1,

5,

6,

7] analyze the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and the creation of new ventures. Accordingly, Alin and Esra [

8], Kobylińska [

9], and Marcon et al. [

10] sought explanations for antecedents, and consequences of entrepreneurial intentions from the perspective of the Theory of Planned Behavior according to the studies of Ajzen [

11,

12,

13].

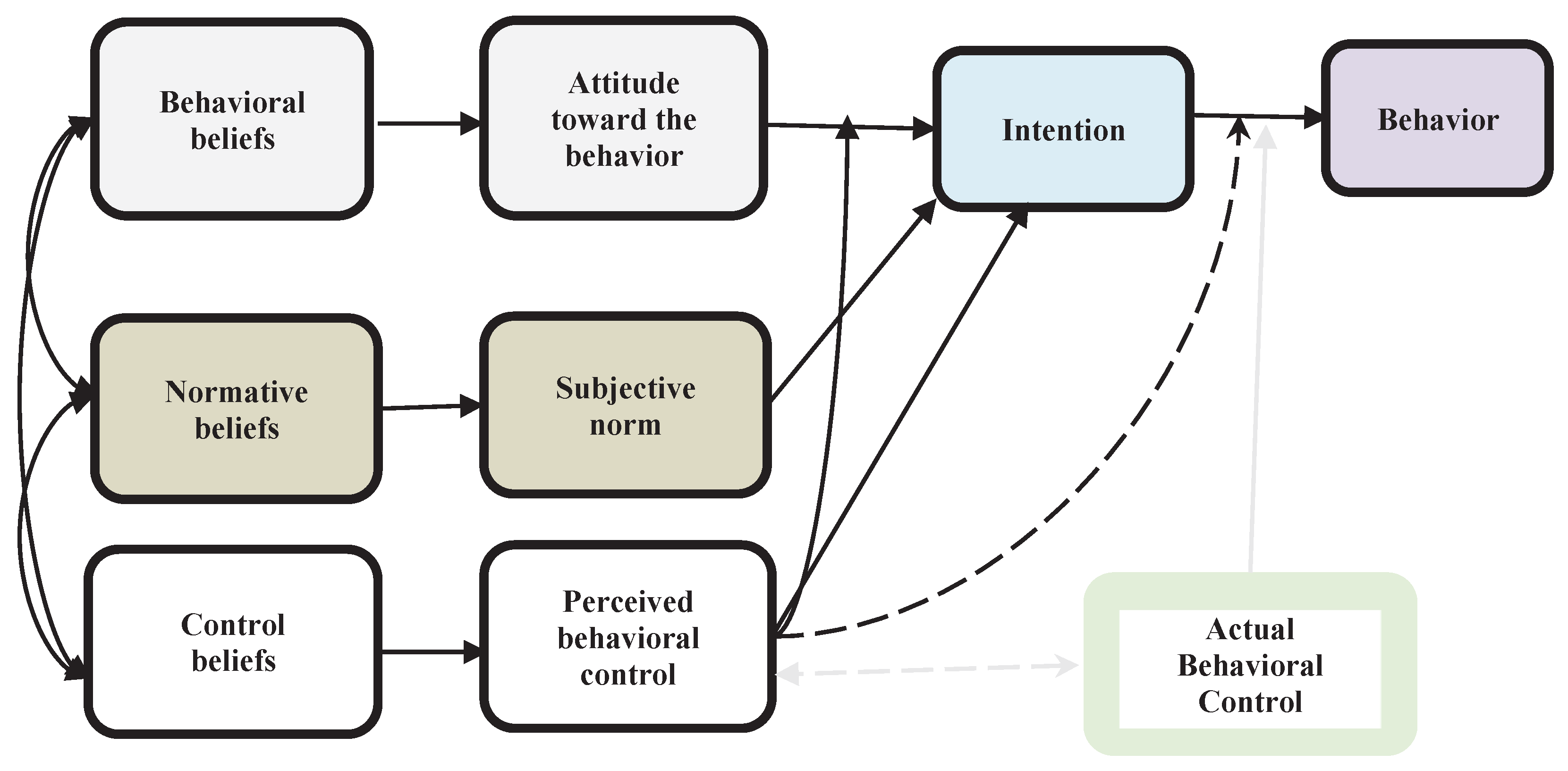

In this context, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) has been one of the most used theories to explain the antecedents and consequences of entrepreneurial intentions in the student field. From a TPB perspective, a person’s behavior is immediately determined by their intention to perform (or not) that behavior. In turn, the intention (EI) of the behavior depends on three factors: the predisposition to perform the behavior (personal attitude), the approval you expect from the people with whom you relate about a certain behavior (subjective norms), and the individual’s perception of their abilities to act (perceived control of behavior). In this way, the intention is the “state of the individual for decision-making, that is, to perform a specific action” [

14] (p. 4).

In this logic, one of the first steps in the entrepreneurial process is the intention, that is, “to feel ready to start a business. The last step of the process is to turn an idea into a business, that is, to act and engage in entrepreneurial activities” [

15] (p. 2). Other studies [

3,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] seek to understand the background of entrepreneurial intentions and the link between intentions and entrepreneurial activity.

Although the results vary between studies [

3,

19,

20], there seems to be a consensus that there is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial intention and some personality factors, such as self-confidence, risk management capacity, need for achievement, and locus of control. However, Kobylińska [

9] points out that a person is surrounded by a variety of contextual factors (business environment, public policies, and education) that also need to be considered by research.

Focusing on the influence of contextual factors on the entrepreneurial intentions of university students, Gieure et al. [

17] used the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to demonstrate the prominent role that education plays in motivating students to undertake at the end of the course. Accordingly, other studies [

3,

15,

16,

18,

19,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] highlight the central role that both factors extrinsic to the individual (family, educational, social, and business environment) and intrinsic aspects (attitudes, subjective norms, need for achievement, self-efficacy, etc.) exert on entrepreneurial intentions and actions.

The students’ involvement in entrepreneurial activity depends on their career plans, their attitude towards self-employment, as well as the influence of cognitive, contextual, and sociocultural factors. The idea that cognitive and environmental predictors drive the individual’s efforts to start a business motivated the conduct of this study and the formulating the following research question: What is the relationship between contextual, personal factors and entrepreneurial intentions of students in the business area from the perspective of the theory of planned behavior?

Given the established problem, the general objective was to analyze the relationship between contextual factors (education, public policies, business environment), personal factors (subjective norms, attitudes, perceived behavioral control), and entrepreneurial intentions of students in the business area from the perspective of the theory of planned behavior. In this way, an attempt was made to identify antecedents that may favor the translation of intentions into entrepreneurship actions in the university context.

This research in this model presents insights for educational policy makers and teaching proposals that promote the formation of entrepreneurs with a sustainable vision of business. Expected to contribute to expanding the literature on the individual factors of the Theory of Planned Behavior in the business area, paying attention to antecedents and their influence on entrepreneurial intention.

Knowing the contextual antecedents of the individual factors formed by the Theory of Planned Behavior [

9] helps undergraduate courses, to develop pedagogical proposals and learning strategies that foster the sustainability of business activities and a culture of student sustainability [

8,

9,

10,

26].

A better understanding of the intrinsic (cognitive) and extrinsic (contextual) aspects that support sustainable interpersonal competencies can contribute to the development of educational policies aimed at green entrepreneurial orientation and the training of leaders capable of recognizing business opportunities and the sustainable development.

It can also be a way for universities and governments to promote sustainable entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility.

1.1. Entrepreneurial Intentions and Theory of Planned Behavior

This section presents and discusses the main concepts and constructs that support the research such as entrepreneurial intentions, Theory of Planned Behavior, entrepreneurship, contextual factors, conceptual model, and study hypotheses, as follows.

Entrepreneurship as a “driving force” for job creation contributes to the social development and economic growth of countries [

3,

16,

18,

19,

25]. In this sense, higher education students are seen as a promising source of entrepreneurs, in such a way that “governments around the world tend to build entrepreneurial ecosystems through the implementation of education proposals” [

27] (p. 1).

Entrepreneurial intention is defined by Gieure et al. [

15] (p. 1) as “behaviors aimed at starting a business, in this context, the intention is the first step” and, in the case of university students, the commitment to start a new business after completing the undergraduate course. For Tomy and Pardede [

28] (pp. 1423-1447), entrepreneurship is an attractive career option for undergraduates. Thus, universities should “focus on developing an entrepreneurial mindset among undergraduate students”.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) developed and expanded by Ajzen [

11] investigates the relationship between intentions and behavior, that is, it assumes that intrinsic and extrinsic factors form the individual’s capacity for behavior and future choices. When applied in the context of entrepreneurship, it contributes to a better understanding of the process of creating new businesses. For Tomy and Pardede [

28], if an individual’s perception of the intention to start a business is positive, their efforts to achieve such a goal will tend to be even greater.

From the TPB perspective, individual intention depends mainly on three determinants: “attitude; subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control” [

12] (p. 2). In this context, volitional control can be predicted from “the individual’s intentions to perform a certain behavior” [

12] (p. 1). These determinants are based on behavioral, normative, and control beliefs. Thus, individual behavior is described as a function of intention and perceived behavioral control [

12] (p. 2).

The subjective norm and the perceived behavioral control lead to the formation of a behavioral intention, as illustrated in

Figure 1, which shows the relationship between the TPB constructs.

The positive relationships between the TPB constructs represented by

Figure 1 explain how attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control can influence human behavior. For Yuzhanin and Fisher [

29], this theoretical model used by research in the area of entrepreneurship focuses on ways to predict planned behavior to understand the antecedents of intentions, especially of university students as potential entrepreneurs.

1.2. Contextual Factors and Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is a process that can be understood through different factors [

22]. Most research on this topic is concerned with personality traits, cognitive behavior of entrepreneurs, etc., however, entrepreneurial motivations have a high propensity to also be influenced by context [

21].

In agreement, Aljaaidi and Waddah [

16] argue that there is a lack of studies that better investigate the influence of contextual factors on intentions and entrepreneurial behavior. This study is based on this knowledge gap and seeks to investigate forces that pressure and/or motivate graduates to get involved in business projects through the economic crisis scenario established by the covid-19 pandemic.

This study focuses on contextual factors described by Goyanes [

30] as pressure situations such as those coming from the family, mainly with a history of entrepreneurship, which motivates their descendants to become entrepreneurs. The attraction factors are related to behaviors such as boldness and proactivity of entrepreneurs in doing something special without external pressure. Accordingly, Aljaaidi and Waddah [

16] point out that formal and informal support has a great impact on entrepreneurial intention. Formal supports refer to government subsidies, favorable policies, easy access to credit, a favorable business environment for nascent entrepreneurs, support from customers, and supplier networks, etc., while informal support includes support from family, parents, friends, and the society [

16].

This study investigates the role of education, the business environment, and government policy as contexts that determine entrepreneurial intentions [

21]. In this logic, Joseph [

31] (p. 2), presents social antecedents (family, education, government policy) as predictors of entrepreneurial intentions. Thus, the factors can represent an attraction factor for one individual and a pressure factor for another. Push and pull factors influence an individual’s motivation for entrepreneurship.

Despite this, according to Kuckertz et al. [

32], entrepreneurs are used to dealing with uncertainty and can demonstrate flexibility and adapt their business models to new situations. It remains for governments, researchers, and educators to investigate the effect of contextual and individual factors on the acceptance of entrepreneurship and the intention to start a business, in order to build frames of reference and information to create alternative and meaningful proposals to motivate both students who already work on their own as well as those who intend to get involved in entrepreneurial projects after graduation.

1.3. Conceptual Model and Hypothesis Development

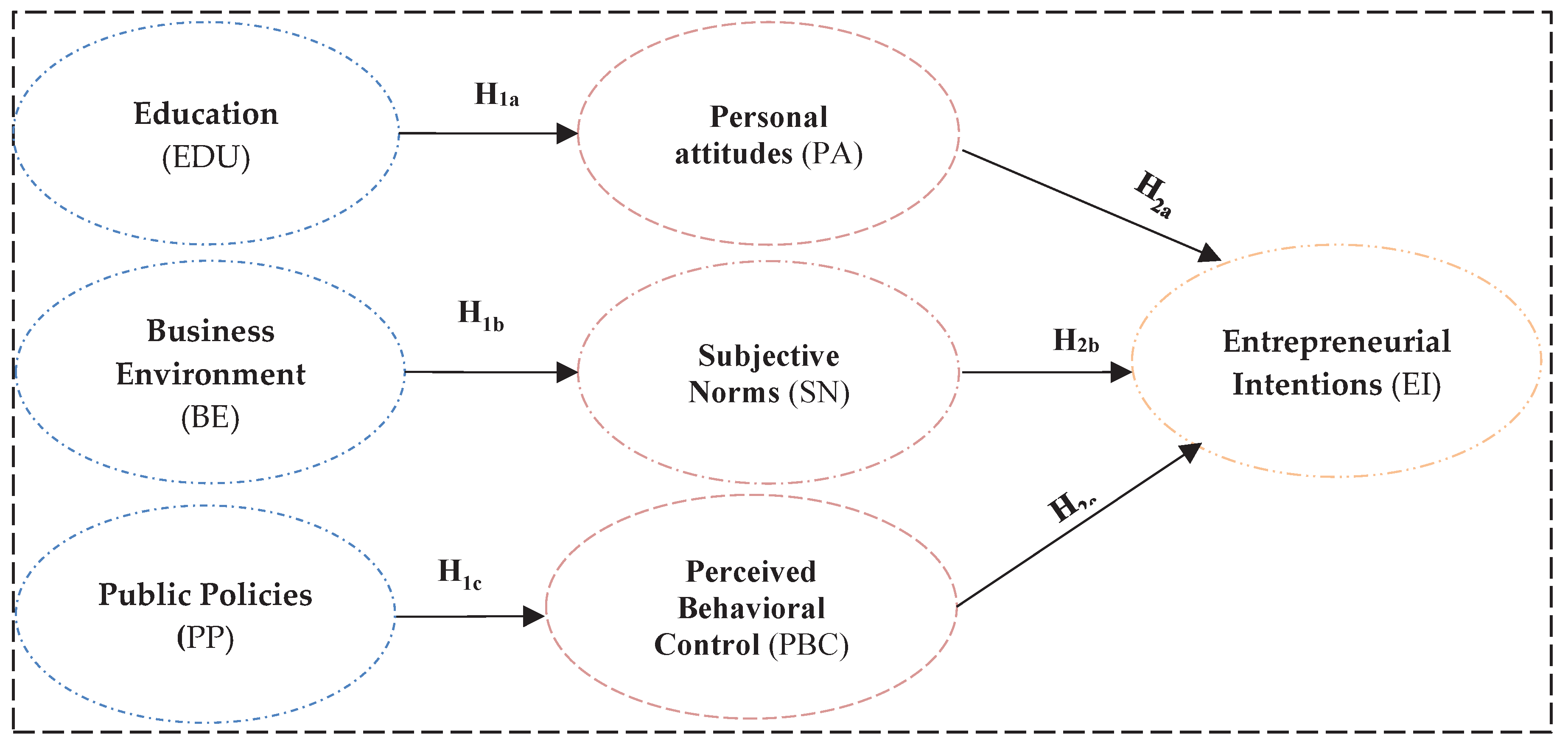

According to the discussions and relations of the previous section, we sought to identify contextual and individual predictives of the entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Brazilian context according to the model applied to Polish students by Kobylińska [

9] (p. 97). In addition, to considering contextual variables to support entrepreneurship, such as education, public policies, business environment, individual factors (subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, personal attitudes) considered predictive of motivations to undertake were tested, as shown in

Figure 2.

As predecessors of intentions, three cognitive TPB variables, closely related to entrepreneurship, were considered: personal attitudes (PA), subjective norms (SN), and perceived behavioral control (PBC). According to the literature review and base model [

9] (p. 97), the need to consider contextual factors to compose the model was noticed such as Education (EDU), Business Environment (BE), and Public Policies (PP) as predictive constructs of Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI). The relationships and rationale for including contextual constructs in the entrepreneurial intention model are described below.

1.3.1. Relationship between Contextual and Individual Factors

The inclusion of issues related to entrepreneurship in educational programs has only become a reality in recent years. Accordingly, Rives and Bañón [

33] highlight that the university and the social environment influence personal attitudes and perceived behavioral control, which, in turn, determine students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Thus, “universities began to understand the importance of the role that entrepreneurship plays in the training of students, which made them start to foster an entrepreneurial culture” [

33] (p. 511). In this context, entrepreneurial education refers to “educational policies and processes that develop and optimize entrepreneurial attitudes, skills, and knowledge” [

9] (p. 97).

In this logic, studies [

10,

26] found that personal attitudes positively influence the entrepreneurial intentions of university students. Accordingly, Choudhury and Mandal [

21] (pp. 2-3) highlight the role of education “as an important predictor in the motivation and decision of nascent entrepreneurs”, so that graduation is a phase of decision and motivation for undergraduate students to pursue an entrepreneurial career. Thus, the development of entrepreneurship education is related to an individual’s perceived entrepreneurial effectiveness. This concept refers to the “belief that the person can successfully carry out entrepreneurial tasks and play the entrepreneurial role” [

21] (pp. 2-3).

Sampene et al. [

34] argued that the construct of education for entrepreneurship mediates the relationship between attitude, subjective norms, perceived entrepreneurial ability, and students’ entrepreneurial intentions. In this way, Kobylińska [

9] (p. 97) adds that the “entrepreneurial effectiveness obtained as a result of the entrepreneurial education process has a positive effect on attitude, increasing entrepreneurial intention”. Bikar et al. [

35] highlight that universities play a key role in providing students with knowledge and information that provides them with the necessary competencies to ensure business sustainability and the expansion of their environmental management skills. In this context, the following hypothesis emerged:

H1a: There is a positive relationship between Education (EDU) and Personal Attitudes (PA).

One of the causes of insecurity and failure in business is the unpreparedness of new entrepreneurs. For Rosário et al. [

36], education plays a fundamental role in expanding the concept of entrepreneurship, which should include a sustainable vision of business, simultaneously involving profit and a positive impact on the environment and society.

Em acordo Diepolder et al. [

37] reitera o papel crucial da educação ao destacar que empreendedores sustentáveis devem possuir conhecimentos empresariais incluindo crenças e valores sociais e ambientais para alcançar a sustentabilidade da cadeia produtiva e dos negócios. In agreement, Diepolder et al. [

37] reiterate the crucial role of education by highlighting that sustainable entrepreneurs must have business knowledge and socio-environmental beliefs and values to achieve the sustainability of the production chain and business.

In this context, Kobylińska [

9] investigated the influence of contextual and individual factors on the entrepreneurial intentions of university students and proposed expanding the investigative framework with the development of a model that includes personal and contextual variables in the entrepreneurial intentions of students in Poland. The findings demonstrate that ecosystems that support entrepreneurship, such as the business environment, public policies, and entrepreneurial education, reinforce attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control and indirectly have positive effects on students’ entrepreneurial intentions.

Other recent studies such as those by Gieure et al. [

15], Georgescu and Herman [

22], Krüger et al. [

38], and Kobylińska [

9] also reported that subjective norms and family context are predictive of students’ intention to become entrepreneurs after graduation. Hence, Paiva et al. [

39] found the influence of the family context on the entrepreneurial intention of Brazilian and Portuguese university students. Additionally, they identified that more men than women intend to create businesses after graduation. In this context, the following hypothesis emerged:

H1b: There is a positive relationship between Business Environment (BE) and Subjective Norms (SN).

Entrepreneurial activities can be explained by the influence of government policies, as new ventures follow regulations and rules issued by governments that can affect entrepreneurial intentions. Regulatory norms and government policy need to be conducive to entrepreneurship. People’s negative view of the political and regulatory framework discourages the development of entrepreneurship. According to Kobylińska [

9] (p. 99), “New regulations and laws can cause a sense of threat to nascent entrepreneurs”.

An important predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intentions is the business environment that should be “attractive for students to think about startups” [

21] (p. 2); small enterprises face difficulties such as the registration process, lack of initial capital, and to make matters worse, there is the age of fresh graduates. In this way, entrepreneurial motivation can be explained by the influences of the business environment (specific ecosystem that supports entrepreneurship). Studies [

15,

21,

22,

38,

39] highlight that norms of conduct and influence of family, friends, and contact with successful people in business are crucial for higher education students to create new businesses.

In the same way, Choudhury and Mandal [

21] (p. 2) define public policies as “regulatory support that includes available subsidies, favorable policies such as easy licensing, favorable tax system for new entrepreneurs”. This influence will be particularly important for the entrepreneur’s perception of control over their behavior, as will feel more confident in achieving their goals when they know that there are public policies to support.

For Kobylińska [

9] (p. 99), “government policy has the function of supporting entrepreneurs through various facilities, such as reducing taxes and bureaucracy with a positive impact on commercial activities”. This support and promotion of entrepreneurial activities will influence the entrepreneur’s perception of behavioral control, as they will feel more confident if they know that the State can support them through various programs, subsidies, or a stable economic situation. In this logic, Choudhury and Mandal [

21] investigated the role of subjective norms, education, public policies, and the business environment in the entrepreneurial intention of university students. The results showed that regulations, norms, and government incentives are decisive in the entrepreneurial intentions of the investigated graduates. Thus, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H1c : There is a positive relationship between Public Policies (PP) and Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC)

1.3.2. Relationship between Individual Factors and Entrepreneurial Intentions

In models that explain the formation of entrepreneurial intention, attitudes influence entrepreneurial intention and behavior through other aspects such as motivation and self-efficacy. The study by Georgescu and Herman [

22] demonstrates that the motivation to start a business is effectively influenced by students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship, and attitude can explain 50% variance. Research on people’s attitudes toward involvement in entrepreneurial activity [

9,

21,

22] highlight that they dedicate effort and time to entrepreneurship and perceive this activity as positive and professionally stimulating.

In agreement, the research Barba-Sánchez et al. [

40], investigated which variables, directly or indirectly, have influence on the entrepreneurial intention of university students in order to adequately plan activities to reinforce such intention for Spanish universities. Alin and Esra [

8] also identified that personal attitude and perceived behavioral control are predictors of students’ entrepreneurial intention. This means that, if students sympathize with entrepreneurial activities, they will be more willing to spend time and effort with involvement in entrepreneurial projects. Thus, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H2a: There is a positive relationship between Personal Attitudes (PA) and Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI).

The favorable attitude of family members towards the decision to start new businesses often translates into the option for an entrepreneurial career. Studies [

15,

22,

38,

39] highlight the existence of a positive relationship between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intentions when they point out that “in regions where there are greater social acceptance for the implementation of entrepreneurial activities, more startups are created” [

21] (p. 2) and, in turn, more companies succeed.

This means that not only financial or managerial assistance, but also psychological support manifested through acceptance of decisions serves as the basis for involvement in business projects. For Gieure et al. [

15], subjective norms directly influence entrepreneurial intentions, norms that govern life in society, such as family, friends, business environment, and public policies are crucial for the creation of new businesses by higher education students. However, an unfavorable attitude of family members toward entrepreneurship often translates into a reluctance to pursue an entrepreneurial career [

9]. Thus, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H2b: There is a positive relationship between Subjective Norms (SN) and Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI).

The Perceived Behavioral Control construct concerns people’s perception of how easy or difficult it is to act [

11], that is, “a sense of being capable, of having the necessary skills to start a business and succeed in it” [

9] (p. 12). Thus, perceived behavioral control is determined by control beliefs about the availability of factors such as market opportunities, financial resources, business support, etc., which can facilitate entrepreneurship actions [

9]. Thus, the greater the belief that the individual is capable of administering and managing their business, the greater the level of entrepreneurial intention.

In this logic, Kobylińska and Martinez Gonzales [

41] (p. 79) stand out that “positive self-concept beliefs positively influence the intention to become an entrepreneur”. Accordingly, Kobylińska [

9] investigated the influence of personal and contextual variables on the entrepreneurial intentions of students in Poland. The results demonstrate that factors related to the entrepreneurship support ecosystem, such as the business environment, public policies, and entrepreneurial education, reinforce attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, leading to a greater intention of students to create a company.

Perceived behavioral control positively influences intention. For Miriti [

42] and Vamvaka et al. [

43], the more positive the attitude and subjective norm, the greater the perceived behavioral control and the person’s intention to perform a specific behavior. In this sense, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H2c: There is a positive relationship between Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) and Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI).

2. Research Methodology

Given the objective of analyzing the relationship between contextual and individual factors and entrepreneurial intentions of students in the business area from the perspective of the Theory of Planned Behavior, a descriptive quantitative study was conducted.

The study was limited to the courses of Accounting, Administration and Economic Sciences of a university center located in the city of São Paulo. The choice of this institution was because it is a pioneer in offering courses in the business area. It has the maximum score (5) in the National Student Performance Examination (Enade) and accepted to be part of this research.

The study included students regularly enrolled in the target courses of the research in the year 2022. The preference for beginner students in the business area because the programs include content related to finance, accounting, economics, in this sense, it is sought to know what the motivations of these students are to undertake, since the theme of entrepreneurship can permeate the disciplines from the early years.

The sample consisted of 1,067 students belonging to the 1st and 2nd periods of the 1st year of each program. Of these, 308 belonged to the Accounting program; 494 to Economics; and 265 to Administration, as listed in Table below.

Table 1.

Total respondents per program.

Table 1.

Total respondents per program.

| Total number of students per 1st-year classes – 1st period 2022 Morning /Night |

| Accounting - Morning |

Economics - Morning |

Administration – Morning |

|

| 62 |

114 |

54 |

230 |

| Accounting - Night |

Economics - Night |

Administration – Night |

|

| 96 |

147 |

79 |

322 |

| Total number of students per 1st-year classes – 2nd period 2022 Morning /Night |

| Accounting - Morning |

Economics - Morning |

Administration – Morning |

|

| 47 |

92 |

50 |

189 |

| Accounting - Night |

Economics - Night |

Administration – Night |

|

| 103 |

141 |

82 |

326 |

| Total 308 |

Total 494 |

Total 265 |

Total 1.067 |

Considering the total number of respondents per program, 240 questionnaires were applied. Of these, 229 were considered valid. To set the minimum size of the sample, the recommendations by Ringle et al. [

44] and Hair Jr. et al. [

45] for the use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) were taken into account. Ringle et al. [

44] (p. 58) recommend calculating the sample size using the G*Power software, which implies “evaluating the construct or latent variable that receives the highest number of arrows or has the highest number of predictors”. Three exogenous latent variables were used, the effect size used was 0.15, the significance level of α was 0.05, and the sample power of 1-β was 0.8. The minimum sample calculated for the model was 77 respondents. Therefore, the sample of 229 valid questionnaires is adequate to the established minimum.

The collection instrument is composed of four questions and two parts: a) part I aimed to collect demographic data of the respondents based on three questions such as gender, age, and enrolled program; b) part II was based on Kobylińska [

9] (p. 13) and Rives and Bañón [

33] (p. 9). The objective was to investigate determinants of entrepreneurial intentions of students in the business area, based on 7 constructs and 26 assertions, as shown in

Table 2. The scale used was a 5-point Likert scale.

To optimize data collection, the questionnaire was prepared as a “Quiz” for students to answer using their smartphones. The researcher applied the instrument in the classrooms of the programs targeted by the research. After reading the informed consent, the objective of the research was to clarify doubts, the researcher asked the students to agree to participate or not in the research. The questionnaire was pre-tested with Accounting students who were not part of the final sample.

Data were analyzed using the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The collected data were duly organized and entered into the SmartPLS software, as it is one of the main tools for analyzing information in the field of applied social sciences. After the descriptive analysis of the demographic data and research constructs, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test was applied, which aims to “test the sample values from a population with normal distribution” [

46] (p. 196). This is the most suitable test to check the normal distribution of samples with more than 50 elements.

To test the research hypotheses, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was applied, using Partial Least Squares (PLS), in the SmartPLS statistical software. The PLS-SEM is advised in studies that seek to check for causal relationships between the latent variables formed by the analyzed constructs [

45]. Before applying the PLS-SEM model, some assumptions must be met for the measurement model. Statistical tests must be performed to check the reliability and validity of the measurement and structuring models [

47].

3. Results

To study the factors influencing people to become entrepreneurs, we used a structural model developed from a set of variables that allow explaining entrepreneurial intention (EI), as this construct is a strong predictor of real behavior. Thus, we sought to define which contextual constructs (education, business environment, and public policies) and personal constructs (attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) positively influence the entrepreneurial intentions of studes in the business area. For this purpose, the measurement model and the structural model were used, as explained below.

3.1. Measurement Model

Before applying the PLS-SEM model, tests of the measurement model were applied to assess its adequacy, namely convergent validity; reliability of internal consistency; and discriminant validity [

47], in addition, the assessment of reflective outer model involves the examining of reliabilities of the individual items (indicator reliability), reliability of each latent variables, internal consistency (Cronbach alpha and composite reliability), construct validity (loading and cross-loading), convergent validity (average variance extracted (AVE) [

48]. The results are presented in

Table 3.

After removing three assertions (BE3, BE4, and EI3) according to

Table 3, due to the low factor loading, four still presented loadings slightly lower than 0.70, but higher than 0.40. However, these assertions were considered in the research, since the AVE values were above 0.5, which suggests adequate convergent validity for all constructs. The tests used to measure the reliability of the constructs’ internal consistency, such as the composite reliability, showed a coefficient greater than the minimum value of 0.70, however, two constructs showed Cronbach’s alpha slightly lower than 0.60, which is why they were considered in the analysis. Finally, the Heterotrait-Monotrait test (HTMT) was used to check the discriminant validity, whose confidence interval for all latent variables does not include a value of 1, therefore the constructs are explicitly independent of each other. After completing the validation of the measurement model, the structural model is analyzed.

3.2. Structural Model

Soon after checking the reliability and validity of the structural model constructs, estimates of the structural equations were calculated by Bootstrapping analysis, to test the power and direction of the variables suggested when examining the collinearity (VIF – Variance Inflation Factor), the relationships of the structural model (hypothesis test), the coefficient of determination (R2), the effect size (f2), and the predictive relevance (Q2) [

47]. The results of the direct analysis and mediation are presented in

Table 4.

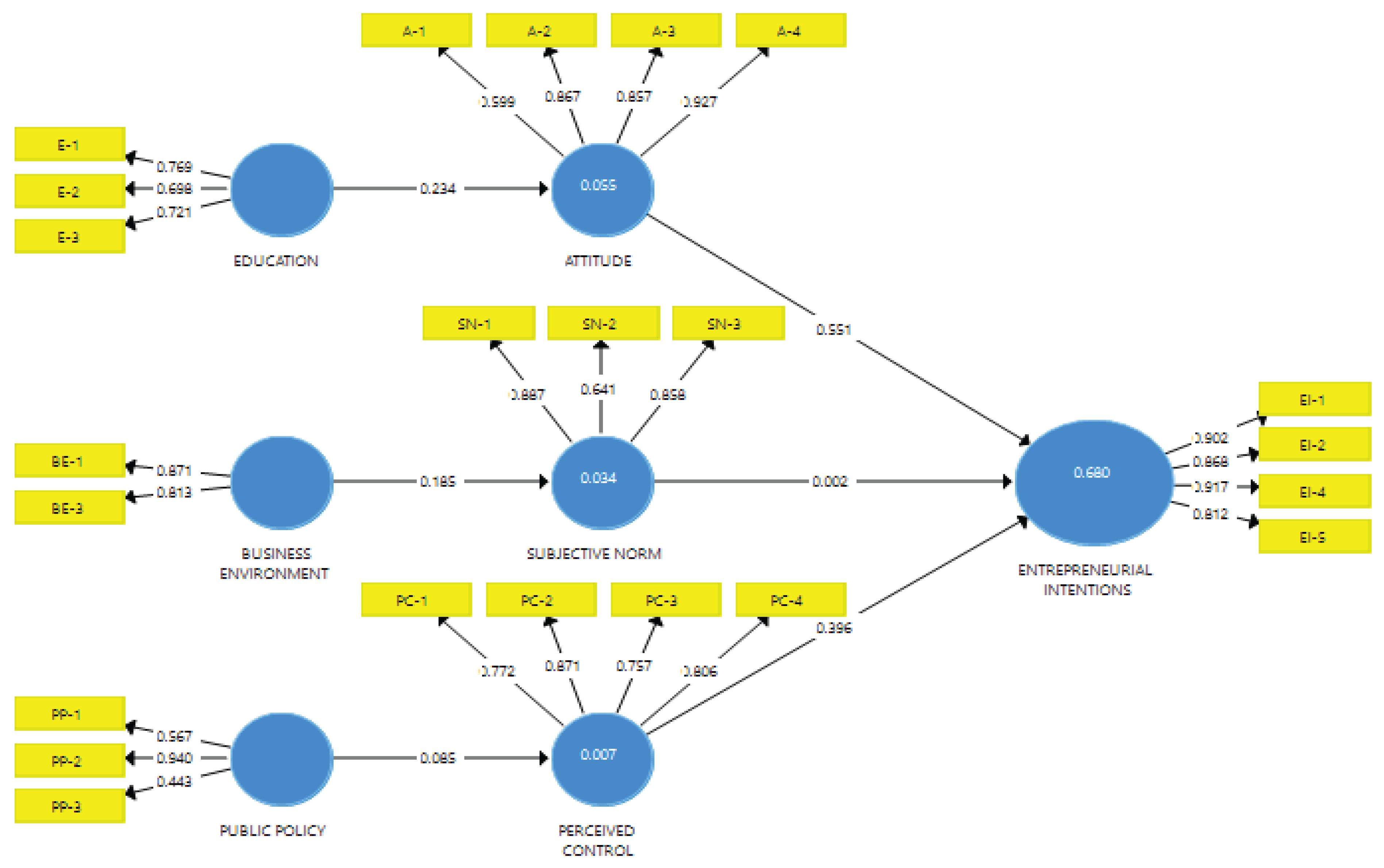

Figure 3 shows the relational model of the research with the results estimated by the modeling PLS-SEM. Data in

Figure 3 indicate which environmental factors were internalized by individual characteristics to indirectly influence entrepreneurial intentions (EI).

For a more accurate analysis of the data in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 was elaborated, which demonstrates which environmental factors are internalized by individual characteristics to indirectly influence the entrepreneurial intentions (EI) of the students investigated.

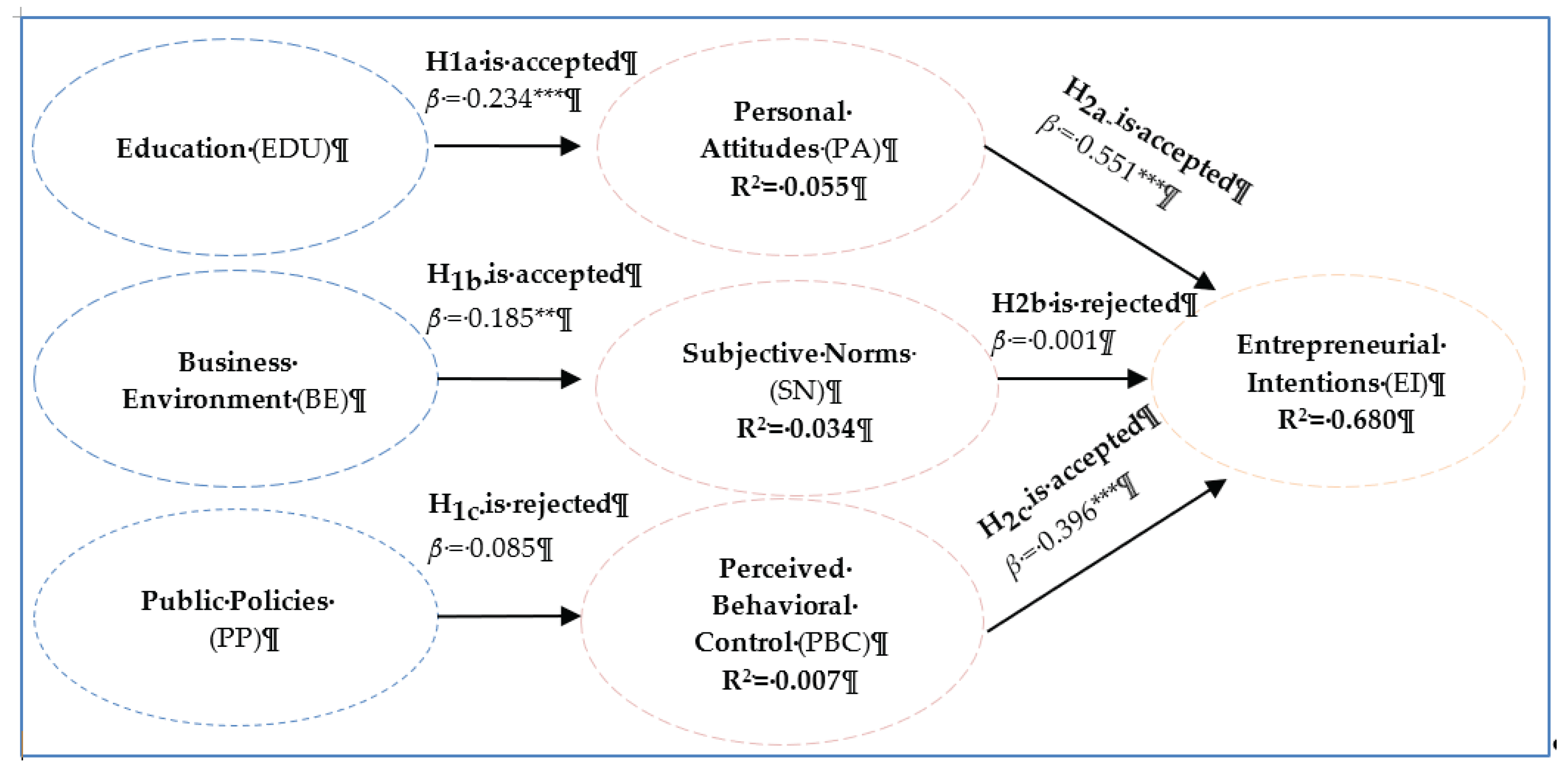

Based on the values of the coefficients of determination (R2) in

Figure 4, education explained personal attitudes by 5.5%, while business environment explained subjective norms by 3.4%. Entrepreneurial intentions were explained in 68.0% (R2) by personal attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral control. Finally, there was a low explanatory value for the variables of the Theory of Planned Behavior, so the findings should be considered with caution.

In summary, the data in

Figure 4 show that: (i) education was a positive antecedent of personal attitudes (β=0.234; p<0.01; t-value=3.380); (ii) business environment was a positive antecedent of subjective norms (β=0.185; p<0.05; t-value=1.998); (iii) public policies showed statistical significance with perceived behavioral control (β=0.085; p>0.10; t-value=0.694); and (iv) personal attitudes (β=0.551; p<0.01; t-value=9.007), and perceived behavioral control (β=0.396; p<0.01; t-value=7.272) were key elements for that students develop entrepreneurial intentions, however (v) subjective norms (β=0.001; p>0.10; t-value=0.041) did not influence the entrepreneurial intentions of the investigated students.

3.3. Discussion of Results

The discussion of the research results is carried out from

Table 5, which presents a summary of the decisions related to the hypotheses tested in the study.

According to data in

Table 5, of contextual factors, their positive influence on personal factors. Hypothesis H1a predicts that there is a positive relationship between education and personal attitudes, and the results support accepting it. Thus, education can be considered a crucial factor in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intentions, as universities are places for preserving norms and values and stimulating students’ entrepreneurial spirit, thus contributing to the promotion of regional development and economic growth. In this context, entrepreneurial education refers to “educational policies and processes that develop and optimize entrepreneurial attitudes, skills, and knowledge” [

9] (p. 97). By accepting hypothesis 1a, this study corroborates recent research by Kobylińska [

9], Aljaaidi and Waddah [

16], Choudhury and Mandal [

21], Georgescu and Herman [

22], Gieure et al. [

15], Gomes et al. [

23], Kisubi et al. [

18], Lopes et al. [

3], Maritz et al. [

24], Mohammed et al. [

19] and Nguyen and Duong [

25].

The second H1b hypothesis established for the development of this study presumes that there is a positive relationship between the business environment and subjective norms, in which the findings support the acceptance of H1b. This result is consistent with Kobylińska [

9], Choudhury and Mandal [

21], Georgescu and Herman [

22], Gieure et al. [

15], Krüger et al. [

38], and Paiva et al. [

39] when noting that the influence of family, friends and contact with successful people in business are crucial for the motivation and involvement of higher education students in business projects. This allows to say that an important predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intentions is the business environment that should be “attractive for students to think about startups” [

21] (p. 2).

H1c predicts a positive relationship between public policies and behavioral control, but the results reject the H1c hypothesis, which contradicts the studies by Kobylińska [

9], Alin and Esra [

8], Choudhury and Mandal [

21] and Rives and Bañón [

33], who argue that the effect of contextual situations depends a lot on how individuals evaluate and respond since any opportunity, resource or difficulty faced depends on individual interpretation. For Aljaaidi and Waddah [

16], public policies such as easy access to credit, a favorable business environment, as well as government policies related to taxes and incentives, combined with good economic and financial conditions in the country, lead students from programs in the areas of applied social sciences to pursue an entrepreneurial career.

Nevertheless, this construct was not statistically significant in this study. This is an important and relevant issue for future research in other regions of the country, as the covid-19 pandemic has had an impact on the economy, entrepreneurship, and working conditions, demanding effective actions from governments and universities.

The digitization of the economy and teleworking are conditions for employability. Even with this scenario, the construct “public policies” showed no significance in the studied context. However, economic development is expected to positively affect entrepreneurship; wealth and prosperity stimulate consumption and investment, which in turn leads to the creation of more entrepreneurial opportunities [

8,

9].

H2a predicts a positive relationship between personal attitudes and entrepreneurial intentions and the results support the acceptance of the H2a. Based on the findings, it is possible to corroborate Kobylińska [

9], Aljaaidi and Waddah [

16], Georgescu and Herman [

22], Gomes et al. [

23], Kisubi et al. [

18], Lopes et al. [

3], Maritz et al. [

24], Mohammed et al. [

19] and Nguyen and Duong [

25]. For Ajzen [

12] (p. 1), when there is a sufficient degree of real control, “individuals are expected to carry out their intentions for such behavior. The intention is then assumed to be the immediate antecedent of the behavior”, thus, intentions prove to be the best predictor of planned behavior.

For Lortie and Castogiovanni [

49] (p. 937), the basic premise of the Theory of Planned Behavior is that “some kind of intentionality regarding behavior precedes any planned behavior”. The results of this study corroborate Marcon et al. [

21] when they found a positive relationship between personal attitudes and entrepreneurial intentions of university students.

H2b predicts a positive relationship between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intentions, but the results reject the H2b hypothesis. This result is consistent with Kobylińska [

9] but contradicts the findings of studies such as Choudhury and Mandal [

21], Georgescu and Herman [

22], Krüger et al. [

38] and Paiva et al. [

39], who identified a positive relationship between students who have entrepreneurial families. For Krüger et al. [

38], subjective norms and family context are predictive of students’ intention to become entrepreneurs after graduation. Paiva et al. [

39] also found a positive relationship between the family context and the entrepreneurial intention of students.

In agreement, Choudhury and Mandal [

21] also highlighted the importance of informal support including support from family, parents, friends, and society. The authors highlight the difficulties of starting and managing one’s own business without a support network, which influences entrepreneurial motivation and can determine the occurrence of entrepreneurial intentions.

H2c predicts a positive relationship between perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intentions and the results support the acceptance of hypothesis 2c, confirming Kobylińska [

9], Aljaaidi and Waddah [

16], Choudhury and Mandal [

21], Mohammed et al. [

19] and Nguyen and Duong [

25]. Perceived behavioral control for becoming or not an entrepreneur is based “on beliefs that groups or individuals should support the creation of a business” [

15] (p. 3).

University students are potential entrepreneurs, at this stage of life, entrepreneurial awareness and the attitude towards a career in this area are under development. College students are potential entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial awareness and attitude towards career at this stage of life are in formation. Therefore, student entrepreneurship is a current and timely topic to expand findings revealed by research such as those carried out by Choudhury and Mandal [

21], Georgescu and Herman [

22], Gieure et al. [

15], Kobylińska [

9], Krüger et al. [

38], Paiva et al. [

39], and others. Bikar et al. [

35] state that, in the post-COVID-19 era, universities can promote employability through programs that promote the enhancement of future administrators’ environmental management skills.

A highlight of this study is the positive relationship between “entrepreneurial education” and “personal attitudes” and their indirect influence on the “entrepreneurial intentions” of the investigated students. These findings corroborate the base model of this research [

9] applied in the context of academics in Poland.

In this logic, cognitive and environmental characteristics favorable predisposition for behavior, in this case, the behavior of creating an enterprise. Ishaq, Sarwar, Aftab, Franzoni, & Raza [

50], add that educational proposals should focus on training leaders capable of identifying the importance of innovation and green entrepreneurial orientation in business sustainability in emerging economies, such as Brazil.

4. Conclusions and Implications

This study analyzed the relationship between contextual factors (education, public policies, business environment), personal factors (subjective norms, attitudes, perceived behavioral control), and entrepreneurial intentions of students in the business area from the perspective of the Theory of Planned Behavior. The results revealed that the education and business environment are predictive of individual factors such as personal attitudes and subjective norms, respectively.

Furthermore, entrepreneurial intentions are influenced by cognitive factors such as a positive assessment of the entrepreneurial career and the perception of the capabilities to start a business. However, public policy had no influenced on the perception of the capacities to undertake; and social pressures no influence entrepreneurial intentions. These data demand greater attention from universities and governments in the promotion and social acceptance of entrepreneurial activities.

The environmental and psychological aspects have a positive and significant influence on the entrepreneurial career intentions of higher education students, which creates space for governments and universities to promote student entrepreneurship. It can be said too that environmental and psychological aspects have a positive and significant influence on the entrepreneurial career intentions of higher education students, which opens space for governments and universities to promote the training of responsible entrepreneurs for sustainable entrepreneurship practices, in order to, in addition to influencing the financial and environmental performance of companies, bring economic and social benefits by adopting responsible business approaches.

This research presents evidence that government policies and learning about entrepreneurship are important to potentialize students’ entrepreneurial characteristics and, consequently, create opportunities for the training of entrepreneurs who want to create sustainable businesses. In addition, the research presents valuable insights for educational institutions and educational policymakers, helping to develop sustainable entrepreneurship models capable of influencing the financial and environmental performance of companies by adopting responsible business approaches. The creation of academic environments that encourage attitudes and behaviors towards sustainable entrepreneurship can be an interesting approach to encourage student entrepreneurship in Brazil.

The world has experienced a health crisis with impacts on entrepreneurship and working conditions, requiring effective action from governments in response to the economic consequences of the covid-19 pandemic. The digitalization of the economy and telecommuting have advanced around the world to maintain the sustainability of business and the employability of graduates. However, not all governments have implemented effective measures to prevent a significant decline in business. Laws, regulations, and severe tax policies can create a sense of threat to entrepreneurs, specifically discouraging young people from choosing an entrepreneurial career.

Despite this scenario, no positive relationship was identified between the constructs "public policies" and "perceived behavioral control" (belief in one’s own ability to carry out the action of undertaking). However, government laws and incentives are key to motivating young people to pursue a career in entrepreneurship after graduation.

Although the study significantly contributes to understanding the entrepreneurial intentions of students in business courses, it is important to highlight some limitations, since aspects underlying the entrepreneurial cognitive process mediated by individual and environmental factors still need to be adequately explained. Initially, it should be noted that the data are based on the perceptions of students in this area, which does not allow generalizing the results to other groups of students.

Based on the findings, it is inferred that contextual factors, such as education and business environment, enhance cognitive aspects, such as personal attitudes, perceptions and beliefs about the ability to open a business. However, other factors such as government incentives and social incentives such as family, friends, the broader professional and cultural environment require the attention of universities and governments to promote entrepreneurship and a favorable assessment of the entrepreneurial career choice and decision of young people to engage in sustainable business projects.

In addition, the entrepreneurial cognitive process can also be explained by other types of research, thus, experimental, qualitative, and longitudinal studies are suggested to provide additional empirical evidence that can support the causes of entrepreneurial intentions, especially in the educational context.

Finally, to advance in the understanding of the phenomenon studied, it would be interesting to include graduate students in administration, both lato sensu and stricto sensu. In addition, replicate the study in undergraduate courses from other areas and regions of the country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G.S. and A.V.T.S.J.; Methodology, V.G.S., A.V.T.S.J. and C.E.F.L.; Software, I.D.S.K., A.V.T.S.J. and V.G.S.; Validation, V.G.S., A.V.T.S.J., V.S., C.E.F.L., I.D.S.K. and R.F.C.; Formal analysis, V.G.S., A.V.T.S.J., I.D.S.K.; Research, V.G.S., A.V.T.S.J. and R.F.C.; Writing – preparation of original draft, V.G.S., A.V.T.S.J., C.E.F.L., I.D.S.K., V.S., and A.L.F.S.V.; Writing—proofreading and editing, V.G.S., A.V.T.S.J., C.E.F.L., I.D.S.K., V.S., R.F.C. and A.L.F.S.V.; Project supervision, V.G.S., C.E.F.L., I.D.S.K. and V.S.; Acquisition of financing, V.G.S. All authors have read and agreed with the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

research was funded by “Centro Universitário da Fundação Escola do Comércio Álvares Penteado – UNIFECAP”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the students, role models, and teachers for donating their time and effort as participants of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study.

References

- Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Cardella, G.M.; Sánchez-García, J.C. Psychological factors that lessen the impact of covid-19 on the self-employment intention of business administration and economics’ students from Latin America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landström, H.; Harirchi, G. That’s interesting! In entrepreneurship research. Journal of Small Business Management 2019, 57, 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.; Ferreira, J.J.; Farinha, L.; Raposo, M. Emerging perspectives on regional academic entrepreneurship. Higher Education Policy 2020, 33, 367–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus (covid-19) and social value co-creation. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 2020, 42, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazeri, G. T.; Anholon, R.; Rampasso, I. S.; Quelhas, O. L.; Leal Filho, W. Preparing future entrepreneurs: reflections about the COVID-19 impacts on the entrepreneurial potential of Brazilian students. Journal of Work-Applied Management 2021, 13, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigos, K.; Michalik, A. The influence of innovation on international new ventures’ exporting in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia countries. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review 2020, 8, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, E.; Stefanescu, D. Can higher education stimulate entrepreneurial intentions among engineering and business students? Educational Studies 2017, 43, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alin, L.D.; Esra, D.İ.L. Determinants of Somali student’s entrepreneurial intentions: the case study of university students in Mogadishu. Eskişehir Osmangazi Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 2022, 23, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylińska, U. Attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control versus contextual factors influencing the entrepreneurial intentions of students from Poland. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics 2022, 19, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, D.L.; Silveira, A.; Frizon, J.A. Intenção empreendedora e a influência das teorias do comportamento planejado e dos valores humanos. Revista de Gestão e Secretariado 2021, 12, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational behavior and human. Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Constructing a theory of planned behavior questionnaire. Psychology Press 2006. (December 05, 2016). Available online: https://people.umass.edu/~aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf.

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Meoli, A.; Fini, R.; Sobrero, M.; Wiklund, J. How entrepreneurial intentions influence entrepreneurial career choices: the moderating influence of social context. Journal of Business Venturing 2020, 35, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieure, C.; Benavides-Espinosa, M. del M.; Roig-Dobón, S. The entrepreneurial process: the link between intentions and behavior. Journal of Business Research 2020, 112, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaaidi, K.S.; Waddah, K.H.O. Entrepreneurial intention among students from college of business administration at northern border University: an exploratory study. SMART Journal of Business Management Studies 2021, 17, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieure, C.; Benavides-Espinosa, M. del M.; Roig-Dobón, S. Entrepreneurial intentions in an international university environment. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 2019, 25, 1605–1620. [Google Scholar]

- Kisubi, M.; Korir, M.; Bonuke, R. Entrepreneurial education and self-employment: does entrepreneurial self-efficacy matter? SEISENSE Business Review 2021, 1, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.A.S.A.; Qataan, A.M.A.; Ghawanmeh, F.; Alqaadan, F. Personality traits, self-efficacy, and students’ entrepreneurial intention towards entrepreneurship – is there a contextual difference. SMART Journal of Business Management Studies 2021, 17, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.L.O.; Almeida, C.de O.; Perez, G.; Slomski, V.G.; de Souza Junior, A.V.T. Fatores determinantes do comportamento empreendedor de concluintes do curso de Ciências Contábeis. Revista Liceu On-Line 2022, 12, 94–124. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, A. H.; Mandal, S. The role of familial, social, educational, and business environmental factors on entrepreneurial intention among university students in Bangladesh. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 17, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M.A.; Herman, E. The impact of the family background on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: an empirical analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Sousa, M.; Santos, T.; Oliveira, J.; Oliveira, M.; Lopes, J. M. Opening the “Black Box” of university entrepreneurial intention in the era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Social Sciences 2021, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritz, A.; Perenyi, A.; De Waal, G.; Buck, C. Entrepreneurship as the unsung hero during the current COVID-19 economic crisis: Australian perspectives. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Duong, D.C. Dataset on the effect of perceived educational support on entrepreneurial intention among Vietnamese students. Data in Brief 2021, 35, 106761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehseen, S.; Haider, S.A. Impact of university partnerships on students’ sustainable entrepreneurship intentions: a comparative study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Song, Y.; Pan, B. How support for university entrepreneurship affects university students’ entrepreneurial intentions: an empirical analysis from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomy, S.; Pardede, E. An entrepreneurial intention model focussing on higher education. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 2020, 26, 1423–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzhanin, S.; Fisher, D. The efficacy of the theory of planned behavior for predicting intentions to choose a travel destination: a review. Tourism Review 2016, 71, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyanes, M. Factors affecting the entrepreneurial intention of students pursuing. Journalism and Media Studies: Evidence from Spain, Int. J. Media Manag. 2015, 17, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, I. Factors influencing international student entrepreneurial intention in Malaysia. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management 2017, 7, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Berger, E.S.; Prochotta, A. Misperception of entrepreneurship and its consequences for the perception of entrepreneurial failure – the German case. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 2020, 26, 1865–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rives, L.M.; Bañón, A.R. El impacto del entorno del estudiante en sus intenciones de crear una empresa cuando finalice sus estudios. Lan Harremanak-Revista de Relaciones Laborales 2015, 32, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sampene, A.K.; Li, C.; Khan, A.; Agyeman, F.O.; Opoku, R.K. Yes! I want to be an entrepreneur: a study on university students’ entrepreneurship intentions through the theory of planned behavior. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikar, S. S.; Talin, R.; Rathakrishnan, B.; Sharif, S.; Nazarudin, M. N.; Rabe, Z.B. Sustainability of Graduate Employability in the Post-COVID-19 Era: initiatives by the Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education and Universities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Raimundo, R.J.; Cruz, S.P. Sustainable entrepreneurship: a literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diepolder, C. S.; Weitzel, H.; Huwer, J. Exploring the impact of sustainable entrepreneurial role models on students’ opportunity recognition for sustainable development in sustainable entrepreneurship education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, C.; Borré, M.L.; Lopes, L.F.D.; Michelin, C.de F. O binômio liderança-empreendedorismo: uma análise a partir da teoria do comportamento planejado. Perspectivas Online: Humanas & Sociais Aplicadas 2021, 11, 26–45. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, L.E.B.; Lima, T. C. B. de; Rebouças, S.M.D.P. Intenção empreendedora entre universitários brasileiros e portugueses. Revista Reuna 2021, 26, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Mitre-Aranda, M.; del Brío-González, J. The entrepreneurial intention of university students: an environmental perspective. European Research on Management and Business Economics 2022, 28, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylińska, U.; Martinez Gonzales, J.A. Influence of personal variables on intention to undertake. A comparative study between Poland and Spain. Engineering Management at Production and Services 2019, 11, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Miriti, G. M. An exploration of entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Kenya. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science 2020, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vamvaka, V.; Stoforos, C.; Palaskas, T.; Botsaris, C. Attitude toward entrepreneurship, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention: dimensionality, structural relationships, and gender differences. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2020, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Silva, D. da; Bido, D.D.S. Modelagem de equações estruturais com utilização do SmartPLS. Revista Brasileira de Marketing 2014, 13, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, T. M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, California, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fávero, L. P.; Belfiori, P. Manual de Análise de Dados: Estatística e Modelagem Multivariada com Excel, SPSS e Stata. Elsevier: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2017.

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Risher, J. J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.M. Discriminant validity assessment: use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, J.; Castogiovanni, G. The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: what we know and future directions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 2015, 11, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M. I.; Sarwar, H.; Aftab, J.; Franzoni, S.; Raza, A. Accomplishing sustainable performance through leaders’ competencies, green entrepreneurial orientation, and innovation in an emerging economy: Moderating role of institutional support. Business Strategy and the Environment 2024, 33, 1515–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).