Submitted:

22 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

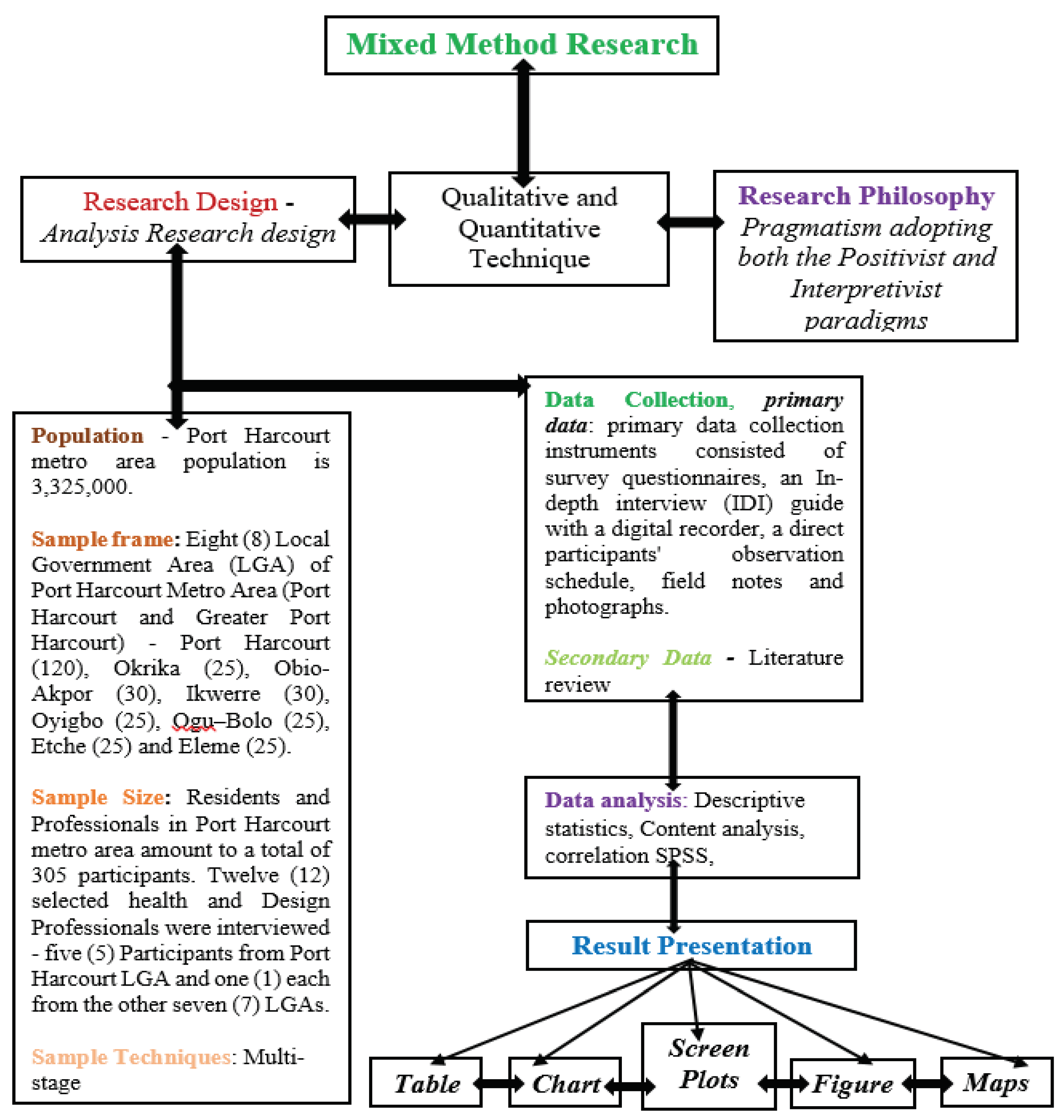

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Sampling Techniques

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Communal Survey

3.4. Recruitment Procedure

3.5. Data Collection

3.6. Ethics

3.7. Data Analysis

4. Results

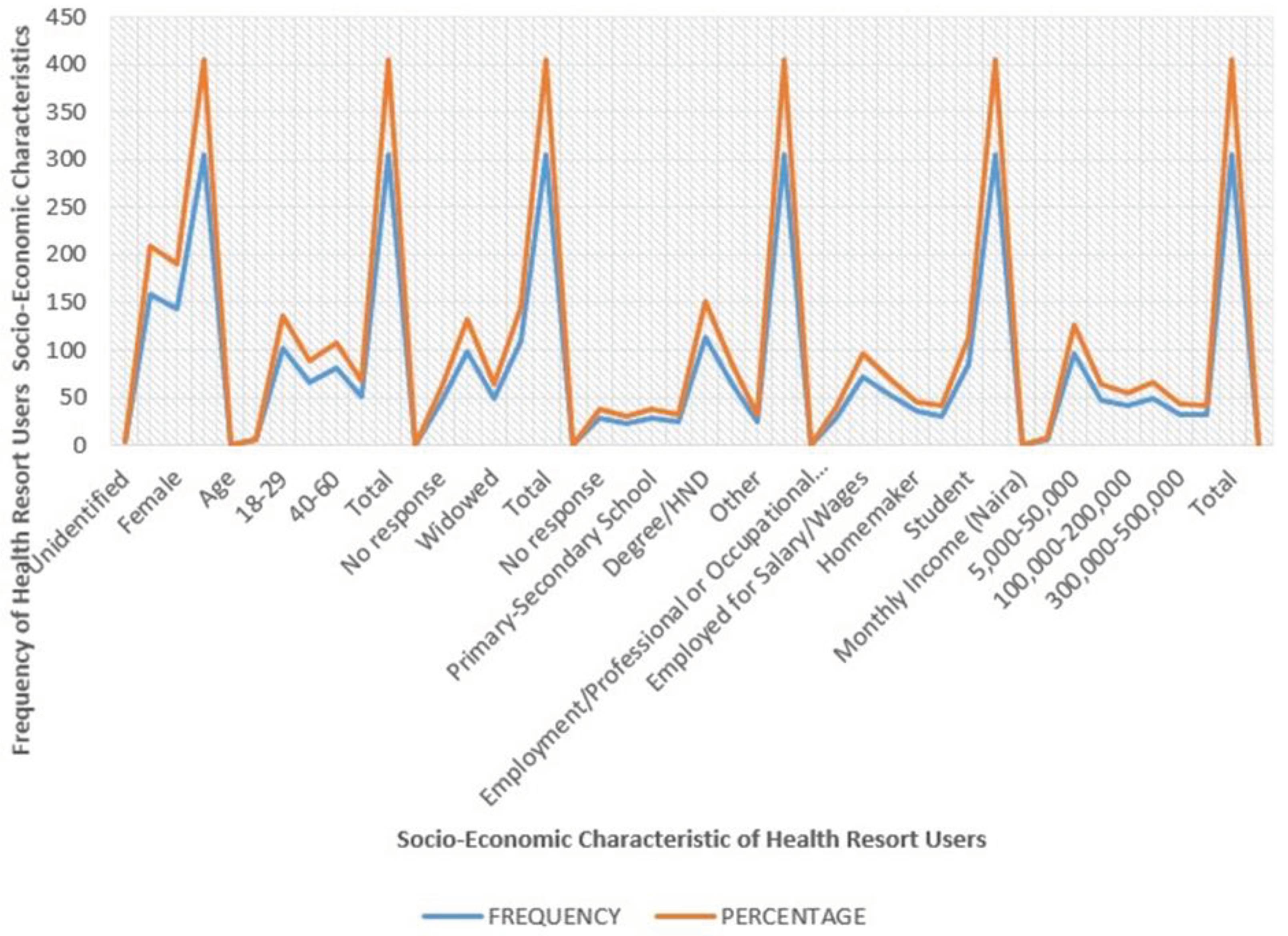

4.1. Result of Socio-economic Characteristics of Health Resort Users

(Medical Doctor, IDI: 2023)The medical director of General Hospital Ogu, Ogu–Bolo LGA, Port-Harcourt, said: “During an assessment, SES is typically broken into three levels (high, middle, and low) to describe the three places a family or an individual may fall into when placing a family or individual into one of these categories, or all of the three variables (income, education, and occupation)”. According to him“People’s SES defines their occupation, income, and education. Lower SES, such as low-income neighbourhood living or having a high-stress, low-control job, is often linked to a wide range of health problems and higher mortality. Therefore, the higher the SES, the healthier they tend to be – a phenomenon often termed the social gradient of health”.(Medical Doctor, IDI: 2023)

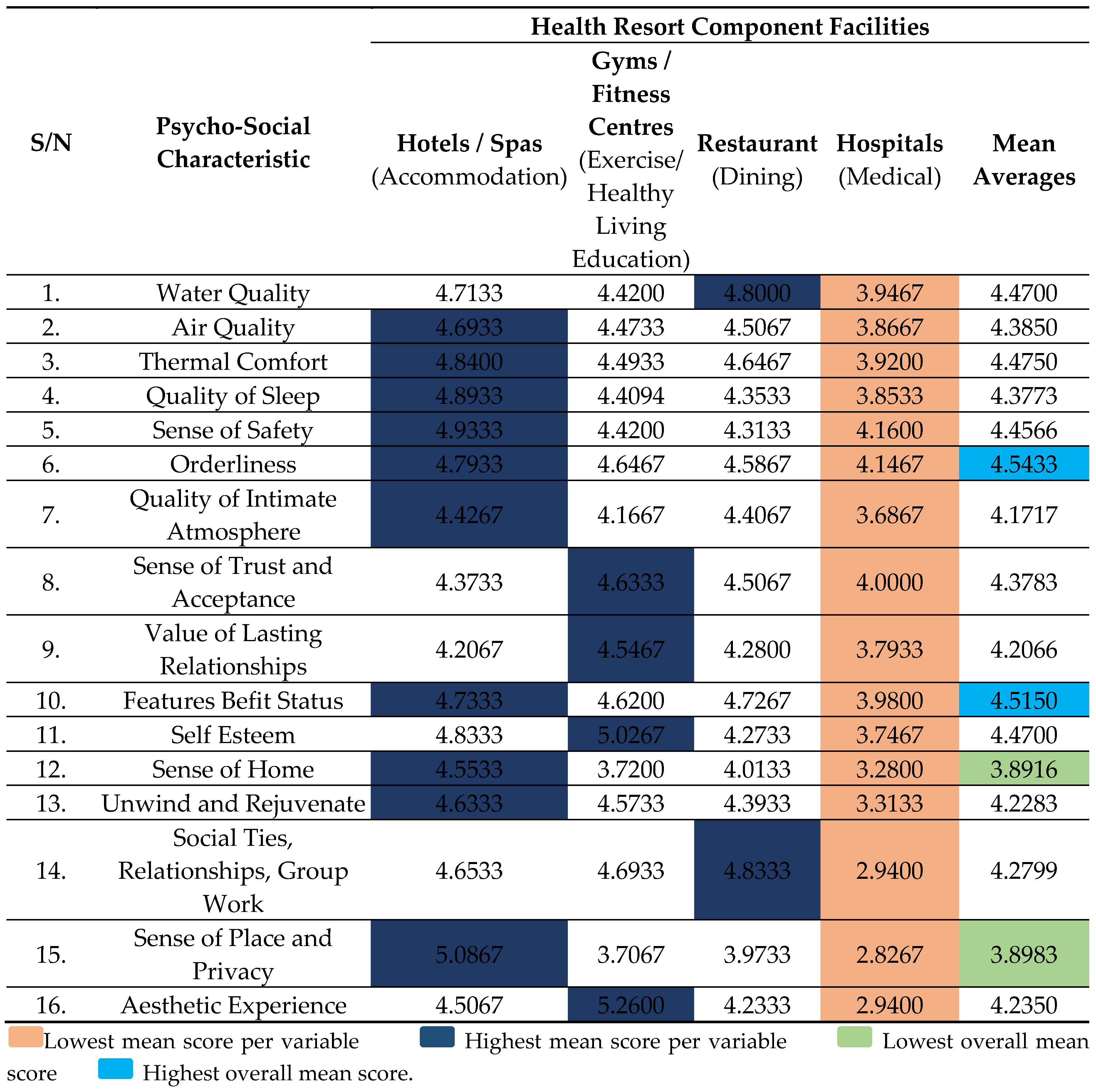

4.2. Result of Psycho-Social Characteristics of the Inclusive Health Resort User

However, the HOD, Psychiatric at General Hospital, Ebubu Eleme, Eleme LGA, Port-Harcourt, said: “Psycho-social characteristics influence an individual psychologically and socially. Explaining that: “Such characteristics can describe individuals with their social environment and how these affect physical and mental health”. Also, he believes that “Better health can lead to healthier lifestyles, better physical health, greater opportunities for educational attainment, greater productivity and economic participation, better relationships with people, more social cohesion, and improved quality of life”.(Psychiatric, IDI: 2023)

The CMO of Heritage Medicare Hospital, Oyigbo LGA, Port-Harcourt, describe psycho-social characteristics as the influences of social factors on individual mental health and behaviour. “Psycho-social adaptations are important because they affect the quality of life and are on the causal pathway to somatic disease”. He further said:“Psycho-social characteristics in healthcare included social resources (social ties, relationships, group work, social integration and emotional support), psychological resources (perceived control, self-esteem, sense of place and privacy, sense of home, sense of safety, sense of coherence, and trust), and psychological risk factors (air quality, water quality, quality of sleep, orderliness, cynicism, vital exhaustion, hopelessness, and depressiveness)”. The findings corroborated the literature in Table 4.(Medical Doctor, IDI: 2023)

4.3. Results of Analysing the Effects of Users’ Psycho-Social and Socio-Economic Characteristics on Their Access to Healthcare

The medical director of Military Hospital, Port Harcourt LGA (PHALGA), Port-Harcourt, corroborated the statement and said: “From experience, lower SES concomitant with reduced access to healthcare, poorer health outcomes, and increased mortality and morbidity. Similarly, higher incomes are usually associated with better nutritional status and medical services. In addition, people with higher levels of education tend to have better health awareness and health-related knowledge. Consequently, higher SES may be simultaneous with better physical health”.(Medical Doctor, IDI: 2023)

In another interview with the chief medical director (CMD) of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Obio-Akpor LGA, Port-Harcourt, he said: “Individuals with low socio-economic status (SES) tend to have less access to healthcare. Adding that SES can significantly affect a patient access to healthcare”. According to him“Low SES adults are less likely to receive preventive services for chronic conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease”. Also: “The consequences of Low SES are significant and include the use of fewer preventive services, poorer health outcomes, higher mortality and disability rates, lower annual earnings because of sickness and disease, and the advanced stage of illness”.(Medical Doctor, IDI: 2023)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alcañiz, M.; Solé-Auró, A. Feeling good in old age: factors explaining health-related quality of life. Heal. Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekhaese, E.N.; A Adejuwon, G.; Evbuoma, I.K. Promoting Green Urbanism in Nigerian Purlieus as Therapy for Psychological Wellbeing/Health. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 665, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palakshappa, D.; Furgurson, K.F.; Harley, M.G.; Bundy, R.; Moses, A.; Taxter, A.J.; Bensinger, A.S.; Cao, X.; Denizard-Thompson, N.; Rosenthal, G.E.; et al. Feasibility of Mobile Technology to Identify and Address Patients' Unmet Social Needs in a Primary Care Clinic. Popul. Heal. Manag. 2021, 24, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.; Ostrom, A.L. Transformative Service Research. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacker, A.; Dion, S.; Grossmeier, J.; Hecht, R.; Markle, E.; Meyer, L.; Monley, S.; Sherman, B.; VanderHorst, N.; Wolfe, E. Social Determinants of Health—an Employer Priority. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 2020, 34, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deesilatham, S. Wellness tourism: determinants of incremental enhancement in tourists’ quality of life. Royal Holloway, University of London; 2016 May. http://www.tourism.jurmala.lv/upload/turisms/petijumi/4wr_wellnesstourism_2020_fullreport.

- Hardan-Khalil, K. Factors Affecting Health-Promoting Lifestyle Behaviors Among Arab American Women. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019, 31, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo, A. A Personalistic Appraisal of Maslow’s Needs Theory of Motivation: From “Humanistic” Psychology to Integral Humanism. J. Bus. Ethic- 2015, 148, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiora, A.I. ; Abiola OB Quality of life (QoL) of rural dwellers in Nigeria: a subjective assessment of residents of Ikeji-Arakeji, Osun-State. Annals of Ecology and Environmental Science. 2017; 1(1):69-75.

- Masiero, S.; Maccarone, M.C. Health resort therapy interventions in the COVID-19 pandemic era: what next? Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 1995–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raheem, T.Y.; Adewale, B.; Adeneye, A.K.; Musa, A.Z.; Ezeugwu, S.M.C.; Yisau, J.; Afocha, E.; Sulyman, M.A.; Adewoyin, O.O.; Olayemi, M.; et al. State of Health Facilities in Communities Designated for Community-Based Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria: A Case Study of Kwara and Ogun States. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Heal. 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global action plan on physical activity 2018-2030: more active people for a healthier world. World Health Organization; 2019 Jan 21. 9241.

- Ekhaese, E.N.; Evbuoma, I.K.; A Adejuwon, G.; A Odukoya, J. Homelessness Factors and Psychological Wellbeing Concerns in Nigerian Cities. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijkelenboom, A.; Verbeek, H.; Felix, E.; van Hoof, J. Architectural factors influencing the sense of home in nursing homes: An operationalization for practice. Front. Arch. Res. 2017, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.M. SKILLS FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL RECOVERY DURING AND AFTER DISASTERS TO STRENGTHEN SOCIAL SUPPORT. Innov. Aging 2019, 3, S391–S391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellena, M.; Breil, M.; Soriani, S. The heat-health nexus in the urban context: A systematic literature review exploring the socio-economic vulnerabilities and built environment characteristics. Urban Clim. 2020, 34, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soedarsono, S.; Mertaniasih, N.M.; Kusmiati, T.; Permatasari, A.; Juliasih, N.N.; Hadi, C.; Alfian, I.N. Determinant factors for loss to follow-up in drug-resistant tuberculosis patients: the importance of psycho-social and economic aspects. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, A.; Villanueva, K.; Rozek, J.; Davern, M.; Gunn, L.; Trapp, G.; Boulangé, C.; Christian, H. The Role of the Built Environment on Health Across the Life Course: A Call for CollaborACTION. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 2018, 32, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belčáková, I.; Galbavá, P.; Majorošová, M. HEALING AND THERAPEUTIC LANDSCAPE DESIGN – EXAMPLES AND EXPERIENCE OF MEDICAL FACILITIES. Int. J. Arch. Res. Archnet-IJAR 2018, 12, 128–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, S. Sustainable Development of Health Resorts in Poland. Barom. Reg. Anal. i Prognozy 2018, 16, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.D.; Ada, M.S.; Jette, S.L. NatureRx@UMD: A Review for Pursuing Green Space as a Health and Wellness Resource for the Body, Mind and Soul. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 2020, 35, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, V. Choudhury R. A study of the factors influencing customer satisfaction in medical tourism in India. International Journal of Business and General Management. 2017; 6(5):7-22. www.iaset.us.

- Ystgaard, K.F.; Atzori, L.; Palma, D.; Heegaard, P.E.; Bertheussen, L.E.; Jensen, M.R.; De Moor, K. Review of the theory, principles, and design requirements of human-centric Internet of Things (IoT). J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 2827–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubino, P.; Martinez-Levy, A.C.; Caratù, M.; Cartocci, G.; Di Flumeri, G.; Modica, E.; Rossi, D.; Mancini, M.; Trettel, A. Consumer Behaviour through the Eyes of Neurophysiological Measures: State-of-the-Art and Future Trends. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 2019, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineer, A.; Gualano, R.J.; Crocker, R.L.; Smith, J.L.; Maizes, V.; Weil, A.; Sternberg, E.M. An integrative health framework for wellbeing in the built environment. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 205, 108253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S.; Lu, C.; Majeed, M.; Shahid, M.N. Health Resorts and Multi-Textured Perceptions of International Health Tourists. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, R.; Vishwakarma, S.; Yadav, S.S.; Stanislavovich, T.A. Community self-help projects. InNo Poverty 2021 (pp. 120-128). Cham: Springer International Publishing. 25 May. [CrossRef]

- Asselmann, E.; Borghans, L.; Montizaan, R.; Seegers, P. The role of personality in the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of students in Germany during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0242904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latunji, O.; Akinyemi, O. FACTORS INFLUENCING HEALTH-SEEKING BEHAVIOUR AMONG CIVIL SERVANTS IN IBADAN, NIGERIA. 2018, 16, 52–60.

- Huang, Y.; Liu, P. An Evaluation of College Students’ Healthy Food Consumption Behaviors. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2020, 19, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.S.; Skou, S.T.; Larsen, A.E.; Bricca, A.; Søndergaard, J.; Christensen, J.R. The Effect of Occupational Engagement on Lifestyle in Adults Living with Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Occup. Ther. Int. 2022, 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, S.; Chi, F.; Weisner, C.; Grant, R.; Pruzansky, A.; Bui, S.; Madvig, P.; Pearl, R. Association of behavioral health factors and social determinants of health with high and persistently high healthcare costs. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 11, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladosun, M.; Azuh, D.; Fasina, F.F.; Akanbi, M.; Amoo, E.; Osabuohien, E.S.; Adekola, P.; Okorie, U. Atteinte des objectifs de developpement durable au Nigeria: Informations sur la dynamique de la population, les relations entre les sexes, les inegalites et l’insecurite. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2021, 25, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaus, S.; Crelier, B.; Donzé, J.D.; E Aubert, C. Definition of patient complexity in adults: A narrative review. J. Multimorb. Comorbidity 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltzman, L.Y.; Hansel, T.C.; Bordnick, P.S. Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy. [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.; D’Ambrosio, L.A.; Felts, A.; Rula, E.Y.; Kell, K.P.; Coughlin, J.F. Reducing Isolation and Loneliness Through Membership in a Fitness Program for Older Adults: Implications for Health. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tull, M.T.; Edmonds, K.A.; Scamaldo, K.M.; Richmond, J.R.; Rose, J.P.; Gratz, K.L. Psychological Outcomes Associated with Stay-at-Home Orders and the Perceived Impact of COVID-19 on Daily Life. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, M.W.; Nápoles, A.M.; Pérez-Stable, E.J. COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phyo, A.Z.Z.; Presidents Malaria Initiative. Quality of life and mortality in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessel, S.; Sawyer, S.; Hernández, D. Energy, Poverty, and Health in Climate Change: A Comprehensive Review of an Emerging Literature. Front. Public Heal. 2019, 7, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ede, J.; Initiative, P.M.; The Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2013 report; Profile, F. A.A.O.O.T.U.N.; 2015, N.C.C.N.; Newspaper, T.L. Increasing access to quality health care using health technology to ‘cut-out’ urban communities in Nigeria. Ann. Glob. Heal. 2016, 82, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloh, H.E.; Onwujekwe, O.E.; Aloh, O.G.; Okoronkwo, I.L.; Nweke, C.J. Impact of socioeconomic status on patient experience on quality of care for ambulatory healthcare services in tertiary hospitals in Southeast Nigeria. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, R.; Rehm, M. Home is where the health is: what indoor environment quality delivers a “healthy” home? Pac. Rim Prop. Res. J. 2019, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasina, F.; Oni, G.; Azuh, D.; Oduaran, A. Impact of mothers’ socio-demographic factors and antenatal clinic attendance on neonatal mortality in Nigeria. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, E.; Li, H. Passengers’ Sensitivity and Adaptive Behaviors to Health Risks in the Subway Microenvironment: A Case Study in Nanjing, China. Buildings 2022, 12, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. Quality-of-life indicators as performance measures. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, F.; Vergara, A.V.; González, F.; Orlando, L.; Valdebenito, R.; Cortinez-O’ryan, A.; Slesinski, C.; Roux, A.V.D. The Regeneración Urbana, Calidad de Vida y Salud - RUCAS project: a Chilean multi-methods study to evaluate the impact of urban regeneration on resident health and wellbeing. BMC Public Heal. 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrae, J.S.; Robinson, J.A.L.; Spain, A.K.; Byers, K.; Axelrod, J.L. The Mitigating Toxic Stress study design: approaches to developmental evaluation of pediatric health care innovations addressing social determinants of health and toxic stress. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, D.; Melo, A.; Moise, I.K.; Saavedra, J.; Szapocznik, J. The Association Between the Social Determinants of Health and HIV Control in Miami-Dade County ZIP Codes, 2017. J. Racial Ethn. Heal. Disparities 2020, 8, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, H.; Silva, S.; Cline, D.; Freiermuth, C.; Tanabe, P. Social and Behavioral Factors in Sickle Cell Disease: Employment Predicts Decreased Health Care Utilization. J. Heal. Care Poor Underserved 2018, 29, 814–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, E.; Blyth, F.M.; Cumming, R.G.; Khalatbari-Soltani, S. Socioeconomic position and healthy ageing: A systematic review of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 69, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoisington, A.J.; Stearns-Yoder, K.A.; Schuldt, S.J.; Beemer, C.J.; Maestre, J.P.; Kinney, K.A.; Postolache, T.T.; Lowry, C.A.; Brenner, L.A. Ten questions concerning the built environment and mental health. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 155, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, E.A.D.P. Maslow Theory Revisited-Covid-19 - Lockdown Impact on Consumer Behaviour. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. (TURCOMAT) 2021, 12, 2445–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz de León-Martínez, L.; de la Sierra-de la Vega, L.; Palacios-Ramírez, A.; Rodriguez-Aguilar, M.; Flores-Ramírez, R. Critical review of social, environmental and health risk factors in the Mexican indigenous population and their capacity to respond to the COVID-19. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 733, 139357–139357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balki, E.; Hayes, N.; Holland, C. Effectiveness of Technology Interventions in Addressing Social Isolation, Connectedness, and Loneliness in Older Adults: Systematic Umbrella Review. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e40125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo, R.R.; Khanal, P.; Shrestha, S.; Mohan, D.; Myint, P.K.; Su, T.T. Determinants of active aging and quality of life among older adults: systematic review. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1193789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; de Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Tzortzopoulos P, Kagioglou M. Healing built-environment effects on health outcomes: Environment–occupant–health framework. Building research & information. 2019, 47, 747–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mashaly, E.T.; Elsayad, N.A.E.; El-Gezawy, L.S.E.-D. THE INFLUENCE OF THE SENSUAL ENVIRONMENT OF THE URBAN SPACE ON THE USERS. Bull. Fac. Eng. Mansoura Univ. 2020, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaz, A.F.H.; Zeina, A.A.M.A. The Perceived Interaction of Sensory Processing in Internal Space, Architectural Surrounds, and Endless Space. International Design Journal 2023, 13, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzosike, T.C.; Jaja, I.D. A household-based survey of the morbidity profile of under-five children in Port Harcourt Metropolis, Southern Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med J. 2022, 42, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okwakpam, A.N.; Ohochukwu, C.P. Rural Insecurity and Urbanization: Empirical Evidence from Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. IIARD International Journal of Geography and Environmental Management. E-ISSN 2504-8821 P-ISSN 2695- 1878, 2022, 8:1 wwwiiardjournalsorg. [Google Scholar]

- Serdar, C.C.; Cihan, M.; Yücel, D.; A Serdar, M. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem. Medica 2021, 31, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimont, A.; Leleu, H.; Durand-Zaleski, I. Machine learning versus regression modelling in predicting individual healthcare costs from a representative sample of the nationwide claims database in France. Eur. J. Heal. Econ. 2021, 23, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Hirose, M. Mixed methods and survey research in family medicine and community health. Fam. Med. Community Heal. 2019, 7, e000086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, Y.C.; Birks, M.; Francis, K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, K. Inductive/Deductive Hybrid Thematic Analysis in Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2022, 17, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.M.; Kobayashi, L.C. Social isolation and loneliness in later life: A parallel convergent mixed-methods case study of older adults and their residential contexts in the Minneapolis metropolitan area, USA. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 208, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuh, D.; Oladosun, M.; Chinedu, S.; Azuh, A.; Duh, E.; Nwosu, J. Socio-demographic and environmental determinants of child mortality in rural communities of Ogun State, Nigeria. 2021.

- Akanbi, M.A. ; Ope BW; Adeloye D.O.; Amoo EO; Iruonagbe T.C.; Omojola, O. Influence of socio-economic factors on the prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 2021; 25(5s), 138-146.

- Timm, S.; Gray, W.A.; Curtis, T.; Sung, S.; Chung, E. Designing for Health: How the Physical Environment Plays a Role in Workplace Wellness. American Journal of Health, 2018; 32(6), 1468–1473.

- Wolkoff, P.; Nielsen, G.D. Effects by inhalation of abundant fragrances in indoor air – An overview. Environ. Int. 2017, 101, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K.T.Q.; Navaratnam, S.; Mendis, P.; Zhang, K.; Barnett, J.; Wang, H. Fire safety of composites in prefabricated buildings: From fibre reinforced polymer to textile reinforced concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 187, 107815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachance, C.C.; Jurkowski, M.P.; Dymarz, A.C.; Robinovitch, S.N.; Feldman, F.; Laing, A.C.; Mackey, D.C. Compliant flooring to prevent fall-related injuries in older adults: A scoping review of biomechanical efficacy, clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and workplace safety. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0171652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinkus, R.T. Love and Belongingness Needs. In: Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.J.; Granger, S. Self-Esteem and Belongingness. In: Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham. 2020:4749-51. [CrossRef]

- Dienst, F.; Forkmann, T.; Schreiber, D.; Höller, I. Attachment and need to belong as moderators of the relationship between thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, E.K.; Smallwood, S.W.; Hurt, Y. Examining social activity, need to belong, and depression among college students. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunen, J.C. Reflection, Sense of Belonging, and Empathy in Medical Education—Introducing a “Novel” Model of Empathetic Development by Literature. J. Med Educ. Curric. Dev. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijnaard, M.D.; van Hoof, J.; Janssen, B.M.; Verbeek, H.; Pocornie, W.; Eijkelenboom, A.; Beerens, H.C.; Molony, S.L.; Wouters, E.J.M. The Factors Influencing the Sense of Home in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review from the Perspective of Residents. J. Aging Res. 2016, 2016, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoof, J.; Janssen, M.L.; Heesakkers, C.M.C.; van Kersbergen, W.; Severijns, L.E.J.; Willems, L.A.G.; Marston, H.R.; Janssen, B.M.; Nieboer, M.E. The Importance of Personal Possessions for the Development of a Sense of Home of Nursing Home Residents. J. Hous. Elder. 2016, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Population Health. Healthy Built Environment Checklist. NSW Ministry of Health. 2020. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/urbanhealth/Publications/healthy-built-enviro-check.

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Yamaura, Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndibuagu, E.O.; Omotowo, B.I.; Chime, O.H. Patients Satisfaction with Waiting Time and Attitude of Health Workers in the General Outpatient Department of a State Teaching Hospital, Enugu State, Nigeria. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Heal. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worth, P.; Smith, M.D. Clearing the Pathways to Self-Transcendence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F. Senada: Harmonising Architectural Elements for the Recovery of Post-partum Depression. Design Ideals Journal, 2021; 3(1). https://journals.iium.edu.my/kaed/index.php/dij/article/view/637.

- Weclawowicz-Bilska, E.; Wdowiarz-Bilska, M. Revitalisations in Polish Health Resorts vs. European Measures. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 112049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.K.S.; Ajisola, M.; Azeem, K.; Bakibinga, P.; Chen, Y.-F.; Choudhury, N.N.; Fayehun, O.; Griffiths, F.; Harris, B.; Kibe, P.; et al. Impact of the societal response to COVID-19 on access to healthcare for non-COVID-19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan: results of pre-COVID and COVID-19 lockdown stakeholder engagements. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2020, 5, e003042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobosi, I.A.; Okonta, P.O.; Ameh, C.A. Socio-economic determinants of demand for healthcare utilization in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State Nigeria. Afr. Soc. Sci. Humanit. J. 2022, 3, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Tao, Y. Associations between spatial access to medical facilities and health-seeking behaviors: A mixed geographically weighted regression analysis in Shanghai, China. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 139, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyoum, M.; Teklesilasie, W.; Alelgn, Y.; Astatkie, A. Inequality in healthcare-seeking behavior among women with pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Women's Heal. 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algren, M.H.; Ekholm, O.; Nielsen, L.; Ersbøll, A.K.; Bak, C.K.; Andersen, P.T. Social isolation, loneliness, socioeconomic status, and health-risk behaviour in deprived neighbourhoods in Denmark: A cross-sectional study. SSM - Popul. Heal. 2020, 10, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifferty, G.; Shirley, H. ; McGloin, /.J.; Kahn, J.; Orriols, A.; Wamai, R. Vulnerabilities to and the Socioeconomic and Psychosocial Impacts of the Leishmaniases: A Review. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 12. [CrossRef]

| S/N | Name | Age | Sex | Marital Status |

Education | Occupation | Years of experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AB | 52 | M | Married | MD | Medical Doctor | 25 |

| 2 | KSA | 55 | M | Married | PhD | Psychiatrist | 30 |

| 3 | LBO | 61 | M | Married | MBChB | Medical Doctor | 35 |

| 4 | SA | 56 | M | Married | M.PH | Public health | 28 |

| 5 | ED | 55 | M | Married | PhD | Biomedical Engineer | 26 |

| 6 | SY | 47 | F | Married | MD | Medical Doctor | 24 |

| 7 | QC | 52 | F | Married | PhD | Quantity surveyor | 26 |

| 8 | BB | 32 | M | Married | M.Sc. | Architect | 17 |

| 9 | AC | 65 | M | Married | B.Eng. | Civil Engineer | 35 |

| 10 | OA | 39 | M | Married | PhD | Medical Doctor | 15 |

| 11 | YM | 46 | M | Married | MBBS | Medical Doctor | 19 |

| 12 | HA | 43 | F | Married | PhD | Architect | 20 |

| Note: Mean Age: 42.3, Mean Years of E: 25.4 MD- Doctor of Medicine, PhD- Doctor of Philosophy, MBChB- Bachelor of Chirurgery, M.PH- Master of Public Health, M.Sc.-Master of Science, B.Eng.-Bachelors of Engineering, MBBS- Bachelor of Surgery, M-Male, F-Female | |||||||

| S/N | Port Harcourt Metro Area (Port Harcourt and Greater Port Harcourt – Eight (8) Local Government Areas (LGA) | No. of Questionnaires administered | No. of questionnaires retrieved | Response Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Port Harcourt LGA (PHALGA) | 150 | 120 | 80 |

| 2 | Okrika LGA | 38 | 25 | 66 |

| 3 | Obio-Akpor LGA | 39 | 30 | 77 |

| 4 | Ikwerre LGA | 40 | 30 | 75 |

| 5 | Oyigbo LGA | 34 | 25 | 74 |

| 6 | Ogu–Bolo LGA | 34 | 25 | 74 |

| 7 | Etche LGA | 34 | 25 | 74 |

| 8 | Eleme LGA | 38 | 25 | 74 |

| Total | 399 | 305 | 76% | |

| S/N | Port Harcourt (PH) Metro Area (PH and Greater pH – Eight (8) Local Government Areas (LGA) |

Health Facilities in respective Local Government Areas (LGA) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Port Harcourt LGA (PHALGA) | Military Hospital, New Mile One Hospital & Rivers State University Teaching Hospital |

| 2 | Okrika LGA | Okrika General Hospital |

| 3 | Obio-Akpor LGA | University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital |

| 4 | Ikwerre LGA | General Hospital Isiokpo |

| 5 | Oyigbo LGA | Heritage Medicare Hospital |

| 6 | Ogu–Bolo LGA | General Hospital Ogu |

| 7 | Etche LGA | Okomoko General Hospital |

| 8 | Eleme LGA | General Hospital, Ebubu Eleme |

| Total | 10 | |

| S/N | Psycho-Social Characteristic | Maslow’s Tier Of Human Need | Empirical Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Water Quality | Biological and Physiological | [2,54,55,72,73] |

| 2. | Air Quality | Biological and Physiological | |

| 3. | Thermal Comfort | Biological and Physiological | |

| 4. | Quality of Sleep | Biological and Physiological | [2,59,74] |

| 5. | Sense of Safety | Safety | [2,75] |

| 6. | Orderliness | Safety | [9] |

| 7. | Quality of Intimate Atmosphere | Belongingness and Love | [76] |

| 8. | Sense of Trust and Acceptance | Belongingness and Love | [77,78,79] |

| 9. | Value of Lasting Relationships | Belongingness and Love | [80,81] |

| 10. | Features Befit Status | Esteem Needs | [54] |

| 11. | Self Esteem | Esteem Needs | |

| 12. | Sense of Home | Aesthetics and Belongingness and Love | [14,82,83] |

| 13. | Unwind and Rejuvenate | Self-actualisation | [54] |

| 14. | Social Ties, Relationships, Group Work | Belongingness and Love | [52,55,84,85] |

| 15. | Sense of Place and Privacy | Transcendence and Self-actualisation | [86,87] |

| 16. | Aesthetic Experience | Aesthetic | [88,89] |

| S/N | Psycho-Social Characteristic | Hotel | GYM | Restaurant | Hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Water Quality | 0.078 | *0.187 | 0.157 | 0.058 |

| 2 | Air Quality | - 0.074 | 0.130 | 0.027 | - 0.004 |

| 3 | Thermal Comfort | 0.067 | 0.096 | 0.142 | - 0.052 |

| 4 | Quality of Sleep | - 0.002 | 0.135 | 0.121 | 0.063 |

| 5 | Sense of Safety | 0.098 | 0.113 | 0.067 | 0.080 |

| 6 | Orderliness | *0.169 | 0.141 | 0.090 | 0.067 |

| 7 | Quality of Intimate Atmosphere | 0.030 | 0.093 | 0.012 | - 0.004 |

| 8 | Sense of Trust and Acceptance | 0.095 | *0.185 | 0.070 | 0.034 |

| 9 | Value of Lasting Relationships | 0.085 | 0.125 | *0.162 | 0.065 |

| 10 | Features Befit Status | 0.118 | *0.177 | *0.174 | - 0.025 |

| 11 | Self Esteem | 0.081 | 0.150 | 0.042 | - 0.008 |

| 12 | Sense of Home | 0.001 | 0.102 | 0.129 | - 0.002 |

| 13 | Unwind and Rejuvenate | 0.054 | -0.015 | - 0.001 | 0.040 |

| 14 | Social Ties, Relationships, Group Work | 0.087 | 0.081 | 0.004 | 0.116 |

| 15 | Sense of Place and Privacy | - 0.009 | 0.051 | 0.071 | 0.035 |

| 16. | Aesthetic Experience | - 0.028 | 0.074 | - 0.033 | 0.137 |

| S/N | Psycho-Social Characteristic | Hotel | GYM | Restaurant | Hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Water Quality | 0.031 | 0.076 | 0.051 | 0.155 |

| 2 | Air Quality | *- 0.213 | 0.068 | - 0.044 | 0.108 |

| 3 | Thermal Comfort | - 0.089 | 0.097 | 0.044 | 0.069 |

| 4 | Quality of Sleep | *- 0.196 | *0.174 | 0.044 | 0.065 |

| 5 | Sense of Safety | *- 0.176 | 0.084 | - 0.083 | 0.039 |

| 6 | Orderliness | - 0.022 | 0.074 | - 0.017 | 0.094 |

| 7 | Quality of Intimate Atmosphere | - 0.092 | 0.123 | - 0.079 | 0.180 |

| 8 | Sense of Trust and Acceptance | - 0.040 | 0.121 | 0.004 | 0.105 |

| 9 | Value of Lasting Relationships | 0.149 | - 0.040 | 0.027 | *0.162 |

| 10 | Features Befit Status | 0.061 | 0.089 | - 0.058 | 0.061 |

| 11 | Self Esteem | - 0.150 | - 0.027 | - 0.019 | 0.076 |

| 12 | Sense of Home | - 0.086 | 0.018 | 0.010 | 0.116 |

| 13 | Unwind and Rejuvenate | 0.112 | - 0.096 | - 0.142 | 0.033 |

| 14 | Social Ties, Relationships, Group Work | 0.108 | 0.057 | - 0.017 | *0.166 |

| 15 | Sense of Place and Privacy | - 0.042 | 0.134 | 0.009 | 0.088 |

| 16 | Water Quality | - 0.040 | - 0.021 | - 0.115 | - 0.061 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).