Submitted:

28 April 2024

Posted:

29 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Database Used for Study

2.3. Ethics Approval

2.4. Study Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Result

Discussion

Limitations of Study

Conclusion and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Press Information Bureau, 2023. Total 13.96 lakh Anganwadis registered under the Poshan Tracker application. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1943759.

- https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/27.

- https://www.measureevaluation.org/rbf/indicator-collections/health-outcome-impact-indicators/children-aged-under-5-years-who-are-underweight.html.

- https://nhm.goa.gov.in/child-health/.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integrated_Child_Development_Services.

- Sahu SK, Kumar SG, Bhat BV, Premarajan KC, Sarkar S, Roy G, Joseph N. Malnutrition among under-five children in India and strategies for control. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2015 Jan-Jun;6(1):18-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal A, Singh J, Ahluwalia SK. Effect of maternal factors on nutritional status of 1-5-year old children in urban slum population. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:264–7.

- Ganesh Kumar S, Harsha Kumar HN, Jayaram S, Kotian MS. Determinants of low birth weight: A case-control study in a district hospital in Karnataka. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:87–9.

- Som S, Pal M, Bharati P. Role of individual and household level factors on stunting: A comparative study in three Indian states. Ann Hum Biol. 2007;34:632–46.

- Xue, P.; Han, X.; Elahi, E.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X. Internet Access and Nutritional Intake: Evidence from Rural China. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingwei Yang., Zhiyong Zhang., Zheng Wang. Does Internet use connect smallholder farmers to a healthy diet? Evidence from rural China. Front. Nutr., 20 April 2023 Sec. Nutrition and Sustainable Diets Volume 10 - 2023 |. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Baojie, and Xin Jin. 2022. “Does Internet Use Connect Us to a Healthy Diet? Evidence from Rural China” Nutrients 14, no. 13: 2630. [CrossRef]

- CUI Yi., Zhao Qi-ran, Thomas Glauben, Si Wei. The Impact of Internet Access on Household Dietary Quality: Evidence from Rural China. Journal of Integrative Agriculture. Available online 23 November 2023.

- Early J, Hernandez A. Digital Disenfranchisement and COVID-19: Broadband Internet Access as a Social Determinant of Health. Health Promotion Practice. 2021;22(5):605-610. [CrossRef]

- Bauerly B. C., McCord R. F., Hulkower R., Pepin D. (2019). Broadband access as a public health issue: The role of law in expanding broadband access and connecting underserved communities for better health outcomes. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 47(Suppl. 2), 39–42. [CrossRef]

- Gelli, A., Margolies, A., Santacroce, M. et al. Improving child nutrition and development through community-based childcare centres in Malawi – The NEEP-IE study: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 18, 284 (2017). [CrossRef]

- https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/child-nutrition/.

- Akhtar S. Malnutrition in South Asia-A Critical Reappraisal. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016 Oct 25;56(14):2320-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deetjen, U. The lifestyle paradox: adverse effects of internet use on self-rated health status. Inf Commun Soc. (2018) 21:1322–36. [CrossRef]

- Rahman A, Rahman MS. Rural-urban differentials of childhood malnutrition in Bangladesh. Int. J. Child Health Nutr. 2019;8(1):35–42. [CrossRef]

- Akram R, Sultana M, Ali N, Sheikh N, Sarker AR. Prevalence and determinants of stunting among preschool children and its urban–rural disparities in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39(4):521–35. [CrossRef]

- Haftom Temesgen Abebe, Getachew Redae Taffere, Meseret Abay Fisseha, Afework Mulugeta Bezabih. Risk Factors and Spatial Distributions of Underweight Among Children Under-Five in Urban and Rural Communities in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: Using Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis. Nutrition and Dietary Supplements 2022:14 pg 21-37.

- Anik, A.I., Chowdhury, M.R.K., Khan, H.T.A. et al. Urban-rural differences in the associated factors of severe under-5 child undernutrition based on the composite index of severe anthropometric failure (CISAF) in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 21, 2147 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Gudu, E., Obonyo, M., Omballa, V. et al. Factors associated with malnutrition in children < 5 years in western Kenya: a hospital-based unmatched case control study. BMC Nutr 6, 33 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Khan N., Mozumdar A., Kaur S. Dietary Adequacy among Young Children in India: Improvement or Stagnation? An Investigation From the National Family Health Survey. Food Nutr. Bull. 2019;40:471–487.

- Longvah T, Khutsoh B, Meshram II, et al. Mother and child nutrition among the Chakhesang tribe in the state of Nagaland, North-East India. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(suppl 3):e12558.

- Gangurde, Shweta; Jadhav, Sudhir L.1; Waghela, Hetal2; Srivastava, Kajal. Undernutrition among Under-Five Children in Western Maharashtra. Medical Journal of Dr. D.Y. Patil Vidyapeeth 16(3):p 386-392, May–Jun 2023. |. [CrossRef]

- Atalell KA, Alemu TG and Wubneh CA (2022) Mapping underweight in children using data from the five Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey data conducted between 2000 and 2019: A geospatial analysis using the Bayesian framework. Front. Nutr. 9:988417. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari D, Khatri RB, Paudel YR and Poudyal AK (2017) Factors Associated with Underweight among Under-Five Children in Eastern Nepal: Community-Based Cross-sectional Study. Front. Public Health 5:350. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Meng S. Impacts of the Internet on Health Inequality and Healthcare Access: A Cross-Country Study. Front Public Health. 2022 Jun 9;10:935608. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duplaga M. The association between Internet use and health-related outcomes in older adults and the elderly: a cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Inform Decis Mak. (2021) 21:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Murarkar, S., Gothankar, J., Doke, P. et al. Prevalence and determinants of undernutrition among under-five children residing in urban slums and rural area, Maharashtra, India: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 20, 1559 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Bhadoria AS, et al. Prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting among children in urban slums of Delhi. Int J Nutr Pharmacology, Neurological diseases. 2013;3(3):323–4.

- Ahsan, K.Z., Arifeen, S.E., Al-Mamun, M.A. et al. Effects of individual, household and community characteristics on child nutritional status in the slums of urban Bangladesh. Arch Public Health 75, 9 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Javanmardi M, Noroozi M, Mostafavi F, Ashrafi-Rizi H. Internet Usage among Pregnant Women for Seeking Health Information: A Review Article. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2018 Mar-Apr;23(2):79-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun Y, Yu J, Chiu Y-L and Hsu Y-T (2022) Can online health information sources improve patient satisfaction? Front. Public Health 10:940800. [CrossRef]

- Hansstein, FV, Hong, Y, and Di, C. The relationship between new media exposure and fast-food consumption among Chinese children and adolescents in school: a rural-urban comparison. Glob Health Promot. (2017) 24:40–8. [CrossRef]

- Joulaei, H, Keshani, P, and Kaveh, MH. Nutrition literacy as a determinant for diet quality amongst young adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Prog Nutr. (2018) 20:455–64. [CrossRef]

- Shaohai Jiang, Iccha Basnyat, Piper Liping Liu. Factors Influencing Internet Health Information Seeking In India: An Application of the Comprehensive Model of Information Seeking. International Journal of Communication, [S.l.], v. 15, p. 22, apr. 2021. ISSN 1932-8036. Available at: <https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16140>.

- Olu O, Muneene D, Bataringaya JE, Nahimana MR, Ba H, Turgeon Y, Karamagi HC, Dovlo D. How Can Digital Health Technologies Contribute to Sustainable Attainment of Universal Health Coverage in Africa? A Perspective. Front Public Health. 2019 Nov 15;7:341. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaimini Sarkar, 2022. Are you staying in age ready city? Science Reporter pg 20-23. https://nopr.niscpr.res.in/bitstream/123456789/60624/1/SR%2059%2810%29%2020-23.pdf.

- Tan SS, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Medical Internet Res. (2017) 19:e5729. [CrossRef]

- Benda NC, Veinot TC, Sieck CJ, Ancker JS. Broadband internet access is a social determinant of health! Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:1123–5. [CrossRef]

- Rubin R. Internet access as a social determinant of health. JAMA. (2021) 326:298. [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.B., Permatasari, P. & Susanti, H.D. The effect of mothers’ nutritional education and knowledge on children’s nutritional status: a systematic review. ICEP 17, 11 (2023). [CrossRef]

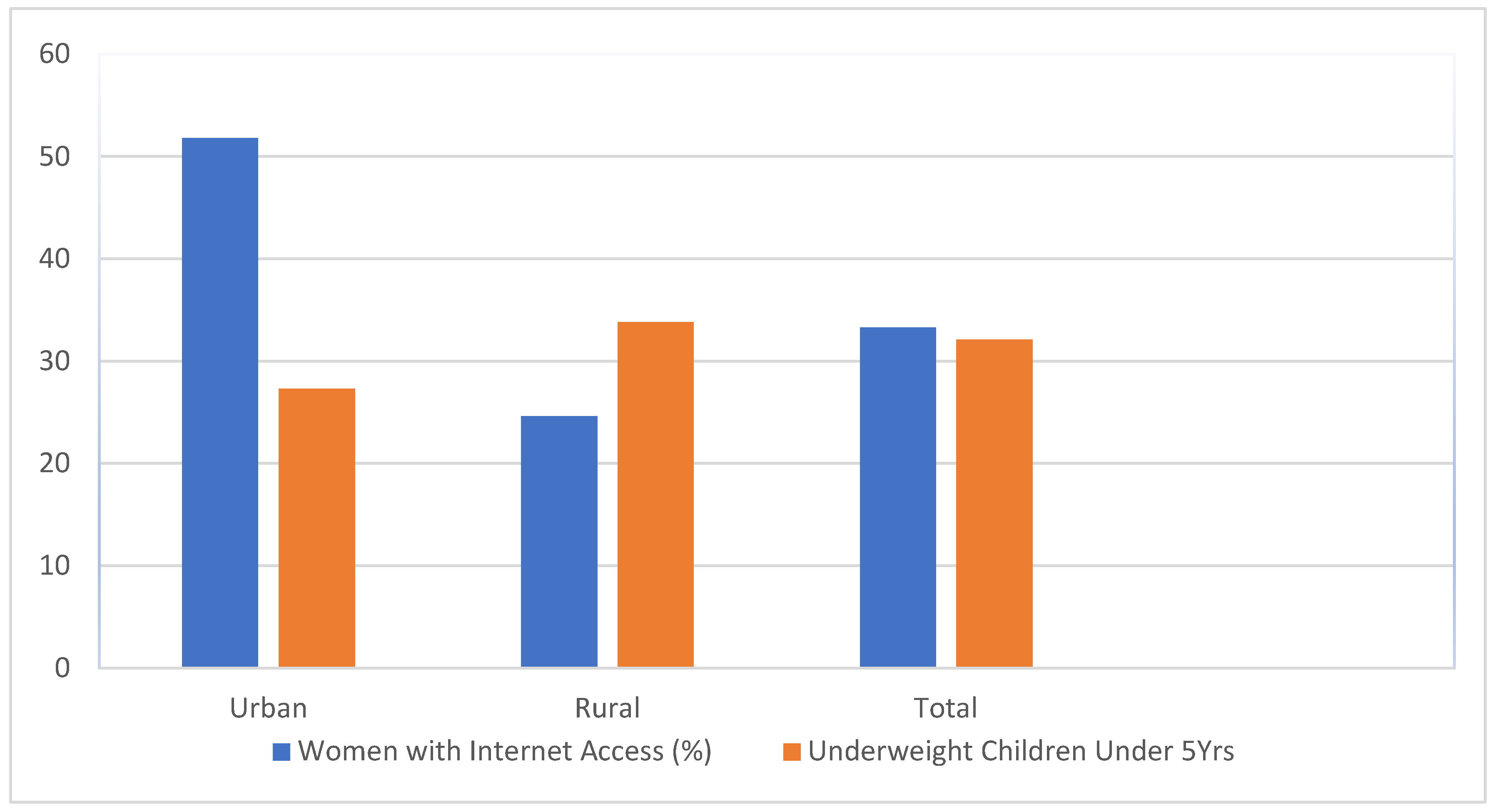

| National level data | % of women with internet access | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) |

|---|---|---|

| Urban women | 51.8 | 27.3 |

| Rural Women | 24.6 | 33.8 |

| Total | 33.3 | 32.1 |

| NFHS 4 (2015-16) | -- | 35.8 |

| States | No. AWC operational | Women with Internet Access (%) | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-5 | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-4 (2015-16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | Total | ||

| Jammu & Kashmir (UT) | 28119 | 55.0 | 38.9 | 43.3 | 19.4 | 21.5 | 21.0 | 16.6 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 18925 | 78.9 | 45.2 | 49.7 | 24.6 | 25.6 | 25.5 | 21.2 |

| Punjab | 27314 | 64.1 | 48.8 | 54.8 | 17.9 | 16.4 | 16.9 | 21.6 |

| Uttarakhand | 20088 | 58.4 | 39.4 | 45.1 | 21.0 | 20.9 | 21.0 | 26.6 |

| Haryana | 25963 | 60.2 | 42.8 | 48.4 | 20.5 | 21.8 | 21.5 | 29.4 |

| Delhi | 10899 | 63.7 | 69.2 | 63.8 | 22.2 | 11.3 | 21.8 | 27.0 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 189024 | 50.2 | 24.5 | 30.6 | 28.2 | 33.1 | 32.1 | 39.5 |

| Chandigarh (UT) | 450 | 75.2 | -- | 75.2 | 20.2 | -- | 20.6 | 24.5 |

| Ladakh (UT) | 1144 | 66.5 | 54.0 | 56.4 | 17.0 | 21.2 | 20.4 | 18.7 |

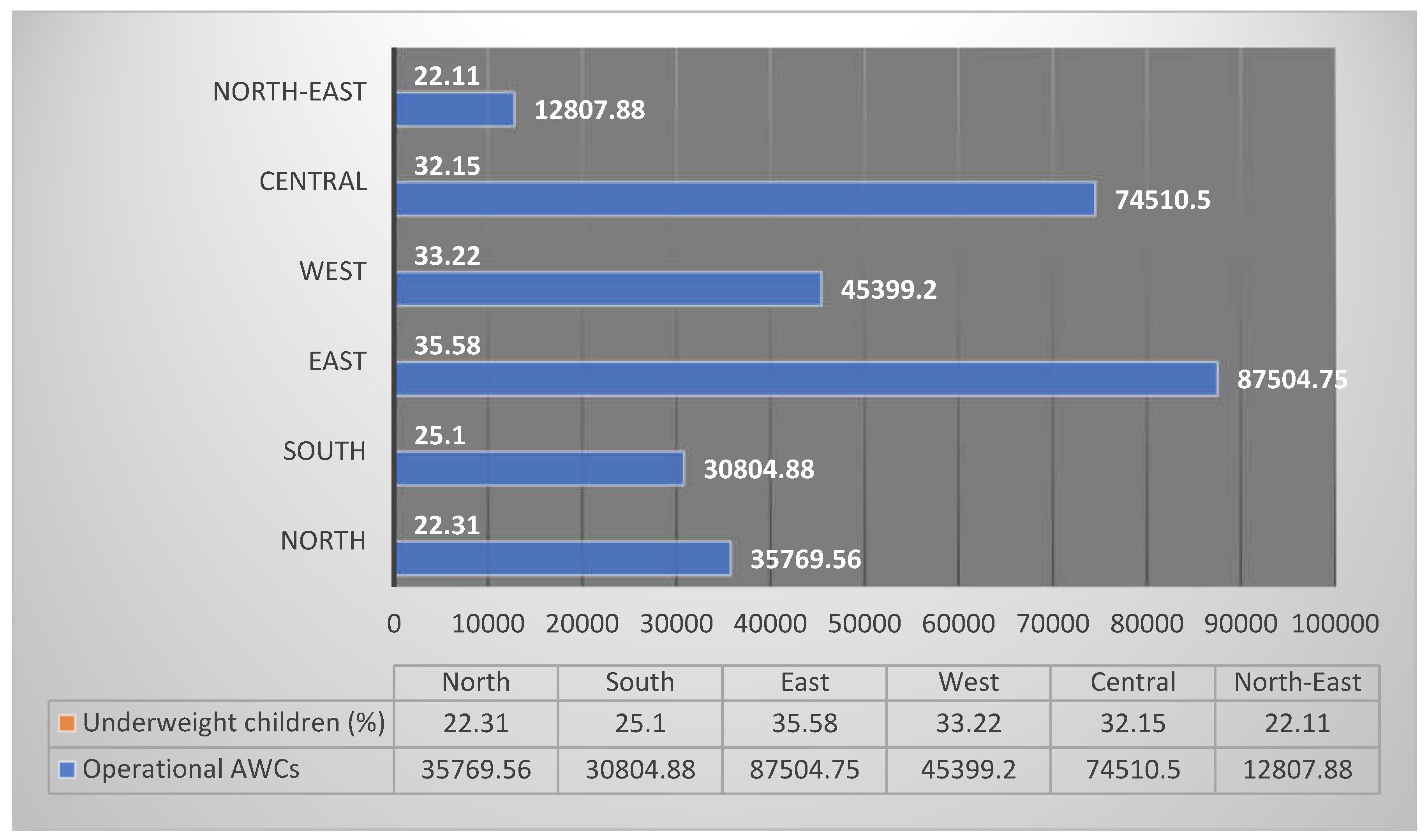

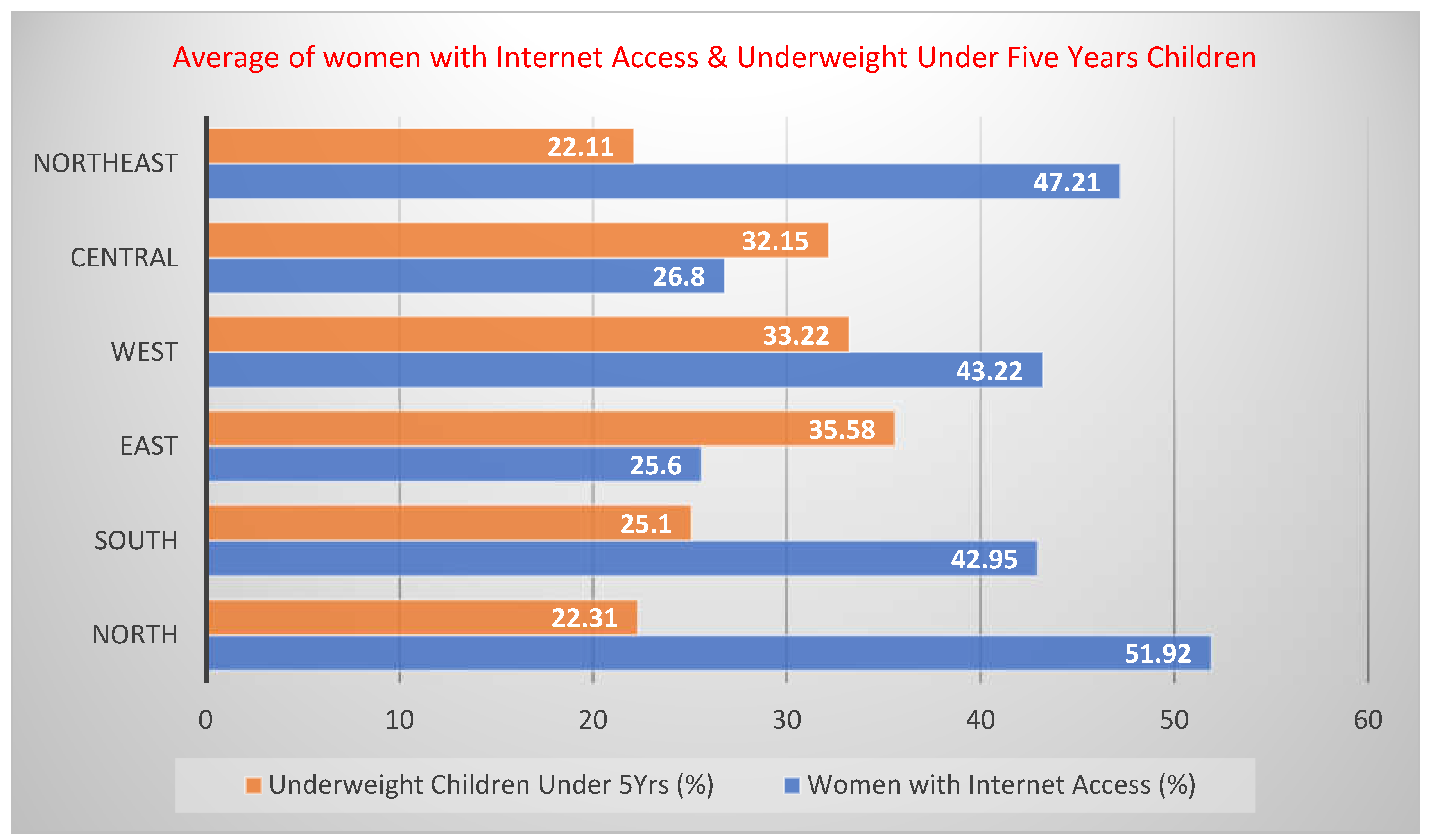

| Mean | 35769.56 | 63.58 | 45.35 | 51.92 | 21.22 | 21.475 | 22.311 | 25.01 |

| Median | 20088 | 63.7 | 44.0 | 49.7 | 20.5 | 21.35 | 21.0 | 24.5 |

| Range | 188574 | 28.7 | 44.7 | 44.6 | 11.2 | 21.8 | 15.2 | 22.9 |

| States | No. AWC operational | Women with Internet Access (%) | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-5 | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-4 (2015-16) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | Total | ||

| Andhra Pradesh | 55615 | 33.9 | 15.4 | 21.0 | 25.1 | 31.4 | 29.6 | 31.9 |

| Karnataka | 65909 | 50.1 | 24.8 | 35.0 | 29.4 | 34.9 | 32.9 | 35.2 |

| Kerala | 33115 | 64.9 | 57.5 | 61.1 | 19.4 | 19.9 | 19.7 | 16.1 |

| Tamil Nadu | 54442 | 55.8 | 39.2 | 46.9 | 20.0 | 23.5 | 22.0 | 23.8 |

| Telangana | 35693 | 43.9 | 15.8 | 26.5 | 25.8 | 35.0 | 31.8 | 28.4 |

| Puducherry (UT) | 855 | 66.9 | 50.4 | 61.9 | 15.9 | 13.7 | 15.3 | 22.0 |

| Andaman & Nicobar (UT) | 720 | 44.1 | 27.9 | 34.8 | 15.1 | 31.1 | 23.7 | 21.6 |

| Lakshadweep (UT) | 90 | 61.8 | 36.0 | 56.4 | 28.5 | 18.4 | 25.8 | 23.6 |

| Mean | 30804.88 | 52.68 | 33.38 | 42.95 | 22.4 | 25.9875 | 25.1 | 25.325 |

| Median | 34404 | 52.95 | 31.95 | 40.95 | 22.55 | 27.3 | 24.75 | 23.7 |

| Range | 65819 | 33 | 42.1 | 40.9 | 14.3 | 21.3 | 17.6 | 19.1 |

| States | No. AWC operational | Women with Internet Access (%) | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-5 | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-4 (2015-16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | Total | ||

| Bihar | 114989 | 38.4 | 17.0 | 20.6 | 35.8 | 41.8 | 41.0 | 43.9 |

| Jharkhand | 38431 | 57.8 | 22.7 | 31.4 | 30.0 | 41.4 | 39.4 | 47.8 |

| Odisha | 74157 | 39.7 | 21.3 | 24.9 | 21.5 | 31.0 | 29.7 | 34.4 |

| West Bengal | 122442 | 48.1 | 14.0 | 25.5 | 28.7 | 33.5 | 32.2 | 31.6 |

| Mean | 87504.75 | 46 | 18.75 | 25.6 | 29 | 36.925 | 35.575 | 39.425 |

| Median | 94573 | 43.9 | 19.15 | 25.2 | 29.35 | 37.45 | 35.8 | 39.15 |

| Range | 84011 | 19.4 | 8.7 | 10.8 | 14.3 | 10.8 | 11.3 | 16.2 |

| States | No. AWC operational | Women with Internet Access (%) | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-5 | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-4 (2015-16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | Total | ||

| Rajasthan | 61873 | 56.1 | 30.8 | 36.9 | 25.4 | 28.1 | 27.6 | 36.7 |

| Maharashtra | 110429 | 54.3 | 23.7 | 38.0 | 33.3 | 38.0 | 36.1 | 36.0 |

| Gujrat | 53027 | 48.9 | 17.5 | 30.8 | 33.3 | 43.5 | 39.7 | 39.3 |

| Goa | 1262 | 78.1 | 68.3 | 73.7 | 22.5 | 26.6 | 24.0 | 23.8 |

| Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Diu & Daman | 405 | 49.4 | 23.8 | 36.7 | 33.6 | 43.5 | 38.7 | 35.8 |

| Mean | 45399.2 | 57.36 | 32.82 | 43.22 | 29.62 | 35.94 | 33.22 | 34.32 |

| Median | 53027 | 54.3 | 23.8 | 36.9 | 33.3 | 38.0 | 36.1 | 36.0 |

| Range | 110024 | 29.2 | 50.8 | 42.9 | 11.1 | 16.9 | 15.7 | 15.5 |

| States | No. AWC operational | Women with Internet Access (%) | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-5 | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-4 (2015-16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | Total | ||

| Chhattisgarh | 51886 | 44.5 | 20.8 | 26.7 | 25.8 | 32.7 | 31.3 | 37.7 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 97135 | 46.5 | 20.1 | 26.9 | 28.6 | 34.2 | 33.0 | 42.8 |

| Mean | 74510.5 | 45.5 | 20.45 | 26.8 | 27.2 | 33.45 | 32.15 | 33.45 |

| Median | 74510.5 | 45.5 | 20.45 | 26.8 | 27.2 | 33.45 | 32.15 | 33.45 |

| Range | 45249 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| States | No. AWC operational | Women with Internet Access (%) | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-5 | % Under-weight children under 5 yrs. (weight-for-age) NFHS-4 (2015-16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | Total | ||

| Arunachal Pradesh | 5642 | 70.0 | 49.6 | 52.9 | 13.1 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 19.4 |

| Assam | 61738 | 49.0 | 24.4 | 28.2 | 25.9 | 33.6 | 32.8 | 29.8 |

| Manipur | 11509 | 50.8 | 40.4 | 44.8 | 12.9 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 13.8 |

| Meghalaya | 5896 | 57.8 | 28.0 | 34.7 | 22.2 | 27.3 | 26.6 | 28.9 |

| Mizoram | 2244 | 83.8 | 48.0 | 67.6 | 9.3 | 15.8 | 12.7 | 12.0 |

| Nagaland | 3980 | 66.5 | 40.3 | 49.9 | 24.5 | 27.7 | 26.9 | 16.7 |

| Sikkim | 1308 | 90.0 | 68.1 | 76.7 | 9.0 | 14.9 | 13.1 | 14.2 |

| Tripura | 10146 | 36.6 | 17.7 | 22.9 | 16.4 | 28.3 | 25.6 | 24.1 |

| Mean | 12807.88 | 63.06 | 39.562 | 47.212 | 16.662 | 22.112 | 22.11 | 19.862 |

| Median | 5769 | 62.15 | 40.35 | 47.35 | 14.75 | 21.55 | 21.55 | 18.05 |

| Range | 60430 | 53.4 | 50.4 | 53.8 | 16.9 | 20.1 | 20.1 | 17.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).