1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and its societal consequences, without a doubt, significantly impacted adolescents’ transition into adulthood. The pandemic, coupled with its associated restrictions and changes, altered normal routines and disrupted many aspects of daily life for all. For adolescents, one of the major impacts of the pandemic was the closure of schools and the start of distance education [

1,

2]. While these changes disrupted learning [

3], they also limited in-person social interactions with peers [

4]. During ontogenesis, a child’s need for stable and safe interactions with family members shifts to include the need for social interactions with other adolescents [

5]. Adolescence is a period of rapid changes in neurodevelopmental [

6] and physical functioning, and therefore it is also a time of increased vulnerability [

7]. Pandemic-related disturbances to this social maturation process, coupled with the stress and uncertainty of the period, may have contributed to an increase in mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, and trauma symptoms, among adolescents [

8,

9,

10].

Previously reported risk factors for mental health problems during the pandemic include a history of mental health problems, a high number of stressful life events, an unstable family environment [

11], and being female [

12,

13]. Past research, however, also identified protective factors for adolescents, such as effective social support and daily routines [

1]. While the loss of social interaction with peers posed a risk factor, maintaining social connections with friends emerged as a protective factor [

14], helping adolescents cope with the challenges and stresses of the pandemic. Physical activity, both individually and as a team activity, also had protective effects on adolescents’ mental health [

15].

The pandemic’s interruption of adolescents’ social interactions with peers also altered their risk behaviours, such as substance use and antisocial behaviours, and influenced the form and frequency of their victimisation. The research on how adolescents changed their behaviours during the pandemic are conflicting, for example, concerning alcohol consumption [

16] and cyberbullying, which was found to both increase [

3,

17] and decrease [

18]. This emphasises the importance of focusing the well-known bio-psychosocial matrix on our behaviours and well-being [

19].

The Swedish government´s strategy to contain the virus emphasised individual responsibility. Recommendations imposed by the government included social distancing, regular and cautious hand hygiene, isolation at home when experiencing any type of symptoms, avoiding physical contact with seniors, avoiding unnecessary travelling and, if possible, working from home [

20]. Even though Swedish adolescents were not affected by a lockdown, they were still required to limit social and physical contact with their peers and relatives.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there were surges in cases (described as waves), during which Swedish public health services enacted certain restrictions and recommendations. In Sweden’s first wave, March 2020 to July 2020 [

21], upper-secondary school students were advised to switch to distance schooling [

20]. Despite some limitations in social contact, it was still possible for adolescents to play sports. From the 15

th of June 2020, distance schooling was withdrawn, and it was announced that education would return to normal during the next semester. By the end of the first wave, 80% of the Swedish population had adapted their everyday lives to decrease the risk of spreading the disease. The results of Kapetanovic et al. [

22] study investigating changes in Swedish adolescents’ psychosocial functioning during this first wave (data collected from 8

th June 2020 to 7

th July 2020) showed that most adolescents followed government regulations. Additionally, most experienced less substance use and victimisation, but poorer mental health. Adolescent girls and those studying through distance schooling were likelier to report negative changes in psychosocial functioning. This can be related to a study by Källmen and Hallgren [

23], where female adolescents, in comparison to male adolescents, reported experiencing poorer mental health outcomes subsequent to exposure to COVID-19. But overall, the results in Kapetanocic et al. [

22] study showed that most did not report any changes. The results also showed that some adolescents reported reduced peer interaction, parental conflict, and feeling a diminished sense of control over their lives. As mentioned above, while there are many research findings concerning the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and health conditions among adolescents during the first wave, there is far less research on the impact of the second wave.

In Sweden, the second wave of the pandemic began at the end of September 2020 and lasted until February 2021, leading to further recommendations. Students of all ages were advised to stay home if they were infected or lived with someone infected with COVID-19. In December 2020, upper-secondary school students had partial distance schooling. At the end of January 2021, Swedish public health services indicated that upper-secondary schools could withdraw partially from distance schooling [

20]. In comparison to other countries around the world, Swedish restrictions on upper-secondary school students were relatively lenient. The present study aims to describe the changes Swedish adolescents reported at the end of the first year (the second wave) of the COVID-19 pandemic, considering their mental health, risk behaviours, psychosocial functioning, and victimisation, and compare the findings for female, male, and non-binary gendered adolescents. During the interpretation of the results, our emphasis lies on discerning the influence of pre-existing salutogenic behaviors in mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and psychosocial well-being of adolescents. This analytical approach not only enriches our understanding but also contributes significantly to the domain of health promotion. Moreover, by scrutinizing the data through a biopsychosocial lens within the context of the pandemic, we aim to shed light on risk behaviors and victimization, thereby augmenting knowledge in the fields of social psychiatry and criminology.

Based on studies from Sweden during the first wave [

22] and from multinational data from the second wave [

24], we hypothesise that Swedish adolescents adapted well to the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore the majority of them did not report negative changes in mental health, risk behaviours, psychosocial functioning, and victimisation. We also hypothesise that there were gender differences in how Swedish upper-secondary school students’ mental health, risk behaviours, psychosocial functioning, and victimisation changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Procedure

The international study Mental and Somatic Health without Borders (MeSHe) (

https://meshe.se/) employed a cross-sectional design and utilised an electronic survey to collect data. The data for the current study were collected in Sweden between September 2020 and February 2021 using this electronic survey. The survey consists of validated questionnaires that assess various aspects of adolescents’ mental and physical health, as well as their risk behaviours. Specifically, the questionnaires in this study address the impact of COVID-19 and changes in adolescents’ behaviours, mental health, and experiences of victimisation during the COVID-19 period.

2.2. Study Population

Despite initial direct contact with the administrations of nearly all Swedish upper-secondary schools at the beginning of the fall semester in 2020, only 292 respondents were obtained, resulting in an unacceptably low response rate. To increase the sample size, the survey was made available on social media platforms during the Christmas holidays of 2020, specifically targeting 15-19-year-old upper-secondary school students. This expanded recruitment strategy yielded a total of 1370 responses, representing all 21 counties in Sweden. Among these 1662 responses, 1608 fulfilled the age requirements set by the national ethical committee. Only one participant did not specify their gender, leaving a total of 1607 female, male, and non-binary gendered Swedish upper-secondary school students whose data was utilised for the present study.

2.3. Instruments

The measures listed below have been previously employed in studies conducted with adolescent populations [

22,

24].

2.3.1. COVID Impact

This item assessed the extent to which COVID-19 personally impacted the lives of adolescents. Participants provided their responses on a numeric analogue scale ranging from 0 (indicating minimal or no effect) to 10 (indicating significant and profound impact).

2.3.2. Changes in Adolescents’ Behaviours during COVID-19

The structure of this measure was originally established through repeated principal component analyses, as outlined in Kerekes et al. [

24]. However, in our study population, the factors described in that research did not demonstrate acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha below 0.5 for each factor). Consequently, in the present study, we chose not to adhere to the factor structure when presenting the results. Instead, we opted to present the items in accordance with their contextual relevance.

2.3.3. Risk Behaviours

including the following: 1) consuming alcohol, 2) getting intoxicated by alcohol, 3) smoking cigarettes, 4) illicit drug use, including prescription drugs used for reasons other than prescribed, 5) arguing/fighting with a parent or parents, and 6) staying outside or being in the city without parents’ knowledge. Cronbach’s alpha for the risk behaviors in the present study was 0.69.

2.3.4. Norm-Breaking Behaviours

consisting of the following: 1) stealing from shops, people, or from own or someone else’s home, and 2) harassing someone on the internet using written language or uploaded pictures and/or videos.

2.3.5. Salutogenic Approaches

incorporating the following: 1) having the opportunity to be in control over one’s daily life, 2) keeping up with school projects and/or work, 3) spending time doing things that one did not have time to do before, 4) working out or exercising, 5) being outside and (for example) taking walks, 6) spending time with family and taking part in fun activities, 7) staying in contact with relatives and friends over the phone/internet, 8) staying connected with friends through social media or video games, and 9) meeting up with friends in real life. Cronbach’s alpha for the Salutogenic approaches, in the present study was 0.60.

Participants were provided with the following response options: I didn’t before and haven’t started after, decreased a lot, decreased a little, no change, increased a little, and increased a lot.

2.3.6. Changes in Adolescents’ Mental Health

This questionnaire comprised 10 items and aimed to evaluate adolescents’ self-reported changes in sleep, stress, satisfaction, loneliness, involvement in society, and various affective states. Participants were asked to rate each item on a response scale consisting of four options: I strongly disagree, I disagree, I agree, and I strongly agree.

2.3.7. Changes in Adolescents’ Victimisation

The frequency of changes in victimisation was evaluated using a subset of five items adapted from the Swedish Crime Survey [

25]. These items included physical violence, threats, sexual harassment, and two items related to online victimisation. Participants rated the frequency of these experiences on a 5-point scale, with response options ranging from decreased a lot to increased a lot.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28. Descriptive statistics, including mean (M), median (Md), standard deviation (SD), and frequencies (%), were utilised to summarise the data. Chi-square tests and risk ratios were employed to compare the prevalence and risks associated with changes in mental health, risk behaviours, psychosocial functioning, and victimisation across genders. The distribution of responses for the COVID-19 impact item was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which revealed a significant deviation (p<0.001) from normality. Therefore, differences in this item between genders were examined using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. The significance level was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Swedish Adolescents

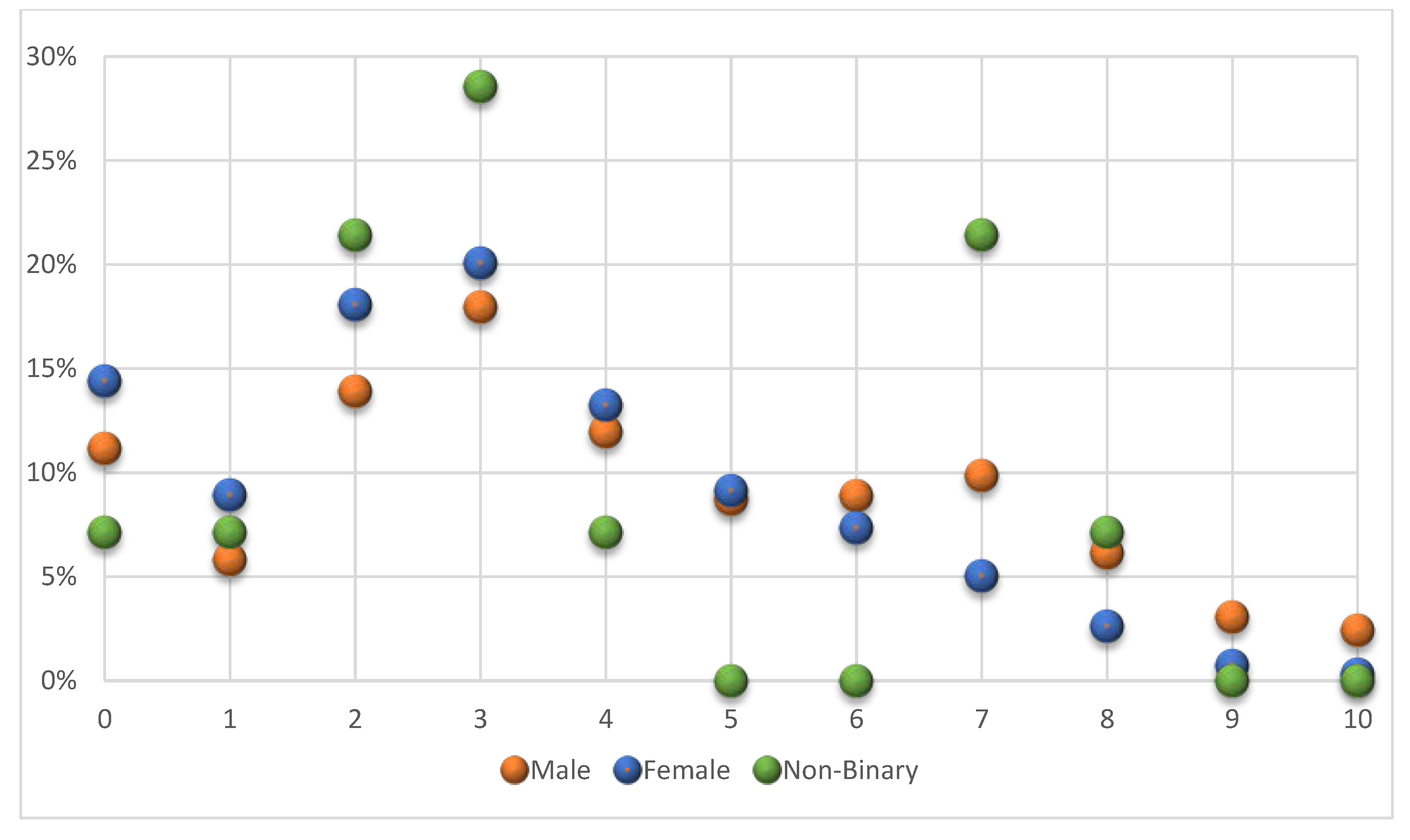

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of responses from Swedish adolescents regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their everyday lives, measured on a scale from 0 to 10. The proportions of male, female, and non-binary gendered adolescents reporting their perceived impact are displayed.

A total of 1,584 participants (98.5% of the study population) provided responses to this question. Among them, there were 618 males, 951 females, and 14 non-binary gendered adolescents. Due to the limited number of non-binary gendered respondents, statistical analysis could not be conducted for this group. The median score for the entire study population was three (Md=3), indicating a moderate level of perceived impact.

Significant gender differences were observed, with male students reporting a significantly higher impact of COVID-19 on their everyday lives compared to female students (Md=4 and 3; M=4.03 and 3.14; SD=2.49 and 2.21, respectively;

p<0.001) (

Figure 1).

3.2. Changes in Swedish Adolescents’ Behaviour During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The questionnaire used in this study aimed to capture any changes in adolescents’ behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic and to determine the direction of those changes. It also assessed whether adolescents had engaged in specific behaviours before the pandemic.

Responses on the absence of these behaviours provide insight into the overall behaviour patterns of Swedish adolescents, regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic. By utilising these data, we can calculate gender-dependent risk ratios for specific defined behaviours.

Regarding risk behaviours, no gender differences were observed in the proportion of adolescents who reported not smoking (approximately 80%), not consuming alcohol (around 50%), and not getting intoxicated by alcohol (approximately 40%). However, significant differences (

p<0.001) were noted in the frequency of illicit drug use and staying outside/being in the city without parental knowledge. Males were 41% likelier to indicate occasional engagement in these behaviours compared to females. On the other hand, females exhibited an increased risk of arguing with their parents even before the COVID-19 outbreak (

Table 1).

In the context of norm-breaking behaviours, there were no gender differences found in the proportion of male and female adolescents, indicating that they had never stolen from shops, people, or their own home (over 90%). However, a slightly higher proportion of females (98%) reported that they had never harassed someone on the internet using written language or uploaded pictures and/or videos compared to male students (96%). This indicated that the male gender was associated with a significant (

p=0.025; 43%) increased risk generally (not as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic) of engaging in harassment (

Table 1).

In terms of salutogenic behaviours, the proportion of adolescents reporting that they had never utilised these approaches was relatively low, ranging from 2% to 13%. Overall, Swedish adolescents indicated a high level of engagement in these behaviours as a general trend. There were, however, significant differences (

p ranging between 0.003 and <0.001) between genders in some of these behaviours. Male adolescents were 36% less likely than females to report that they had never been outside, 34% less likely than females to report that they had never used phone/internet to keep in contact with relatives and friends, and 39% less likely than females to report that they never met with friends in real life. In other words, these behaviours were more often present in female adolescents’ behaviour even before the COVID-19 outbreak. Conversely, a higher proportion of female students reported that they had never used social media or video games to stay in contact with friends (14% vs. 8% of males), indicating that this type of behaviour is generally more associated with males (

Table 1).

Table 2 describes the proportion of adolescents who reported changes (either a decrease or increase) compared to those who reported no change in these behaviours (including responses indicating that they had never engaged in the behaviour or that it remained unchanged during the COVID-19 pandemic) (

Table 2).

For most behaviours, there were no significant differences in the proportion of male and female students who reported changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, females reported a significantly higher proportion of changes in four behaviours—spending quality time with family, having the opportunity to control everyday life, frequency of arguments with parents, and frequency of meeting friends in real life. On the other hand, males reported a significantly higher proportion of changes in two behaviours—illicit drug use and staying in contact with friends via social media (

Table 2).

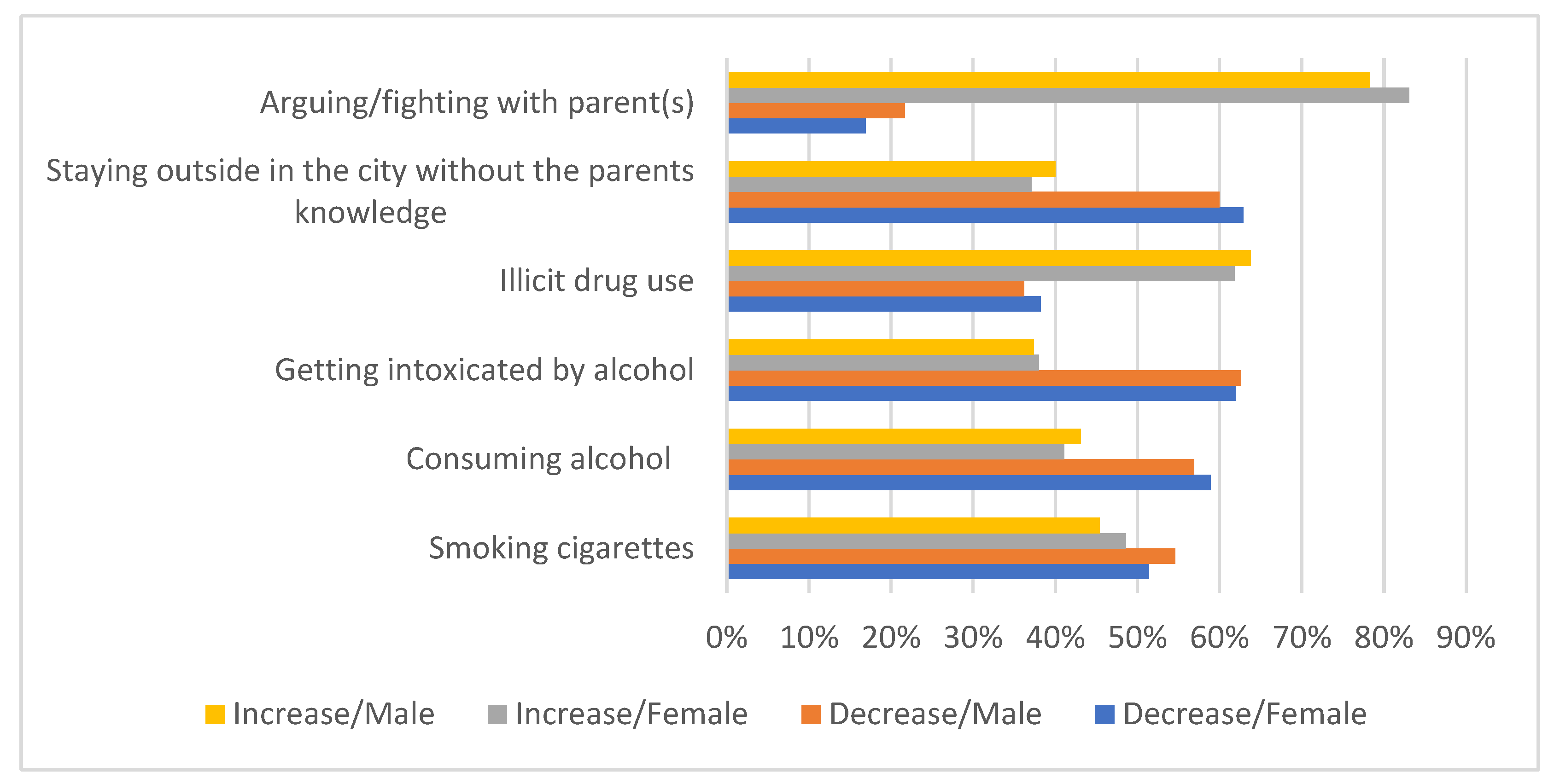

Risk behaviours generally decreased in a higher proportion among both male and female adolescents, with the exception that a greater proportion of male students (

p=0.83) reported increased illicit drug use, and a larger proportion of female students (

p=0.15) reported an increase in the frequency of arguing with their parents. (

Figure 2).

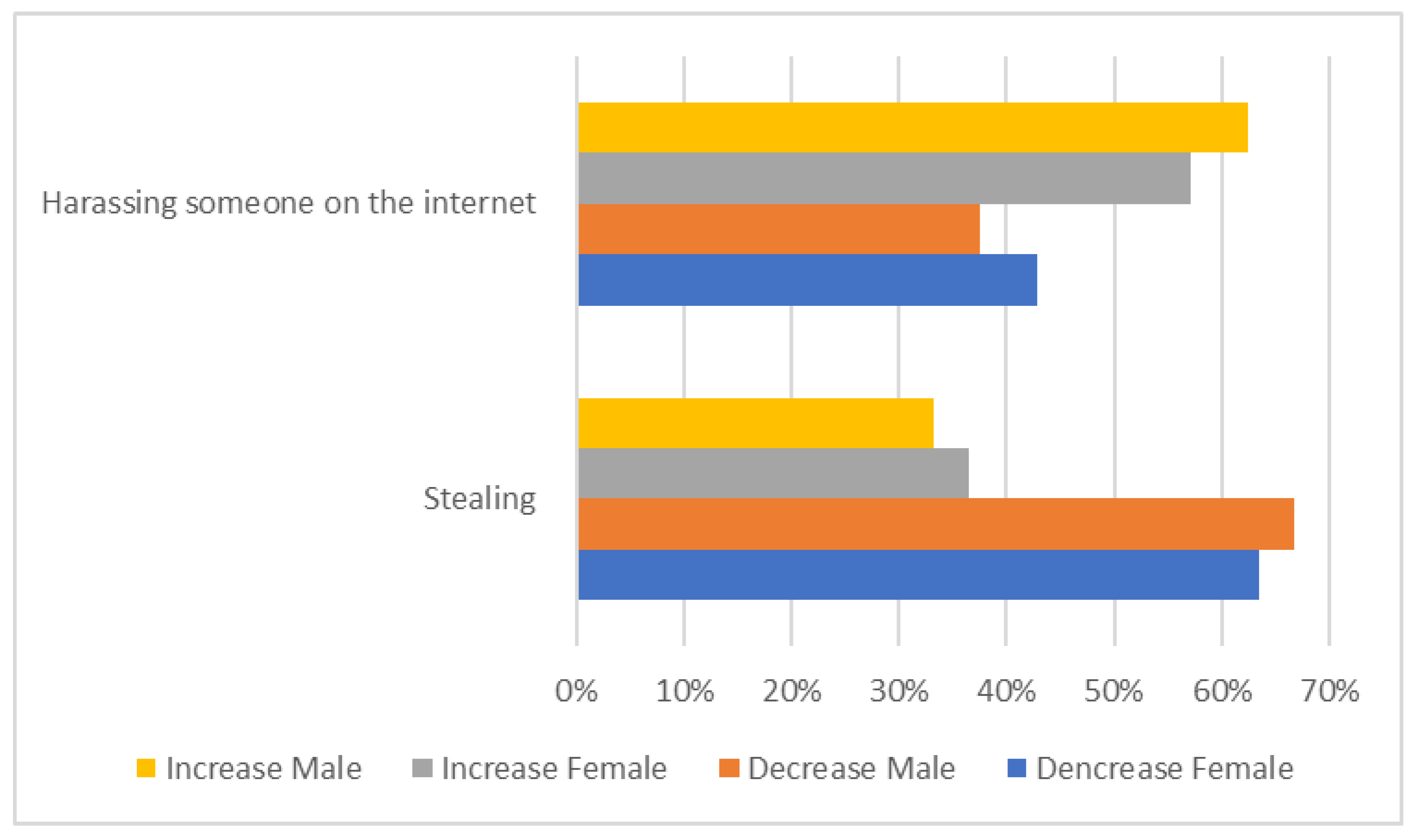

No significant differences were found between females and males in the proportion of adolescents who reported an increase or decrease in either of the two norm-breaking behaviours. Both males and females reported similar proportions, with the majority indicating a decrease in incidents of stealing while reporting an increase in incidents of harassing someone over the internet (

Figure 3)

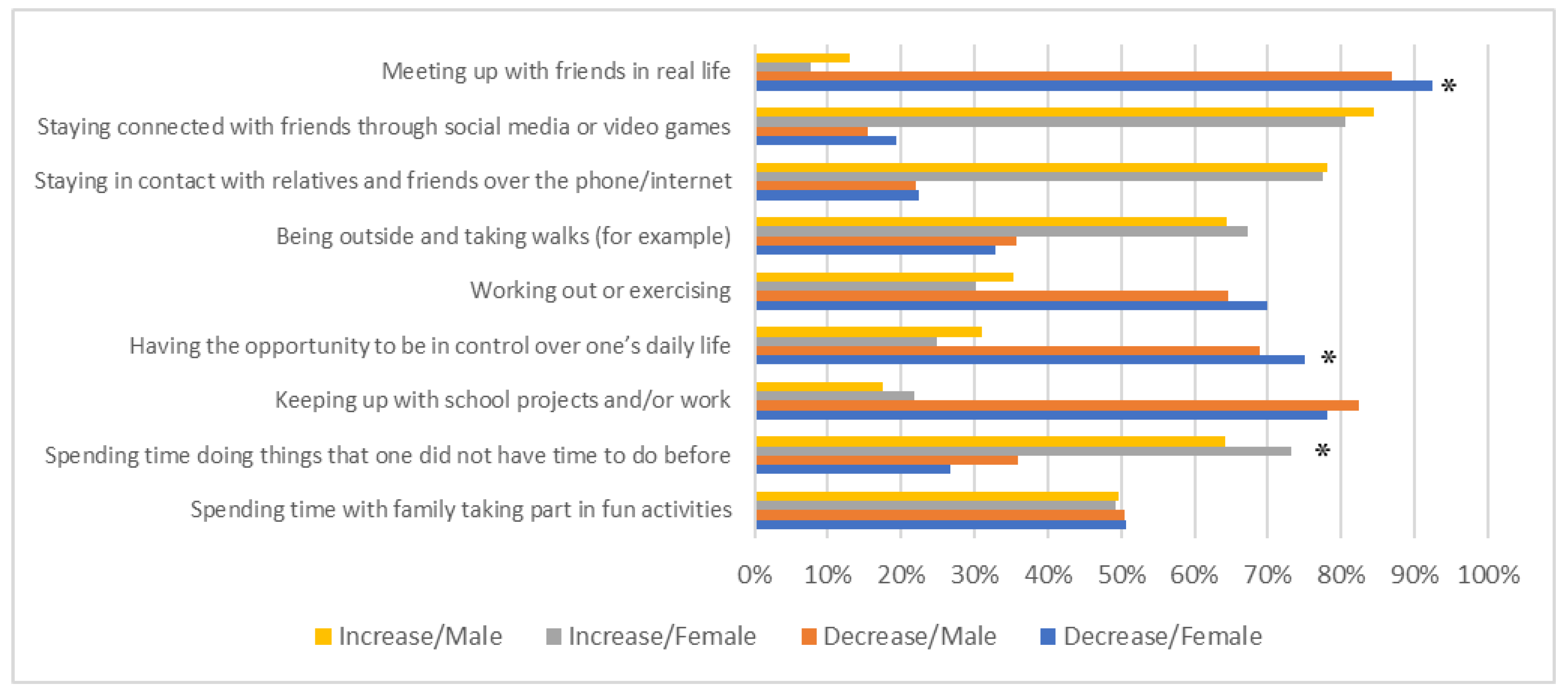

Significant gender differences were found within reported changes in salutogenic behavioural approaches. Specifically, 73% of females reported an increase in “spending time doing things that I did not have time to do before," compared to 64% of males (

p=0.005). Additionally, 75% of females indicated a decrease in having a sense of control over one´s daily life, while 68% of males reported a decrease in this aspect (

p=0.029). Furthermore, a significantly higher proportion of female adolescents (

p=0.002) reported a decrease in meeting up with friends in real life. (

Figure 4).

In general, among those who reported any changes, a higher proportion indicated a decrease in their ability to keep up with schoolwork, having control over their lives, and engaging in exercise. On the other hand, a higher proportion reported an increase in the frequency of spending time doing things that they did not have time to do before (

Figure 4).

3.3. Changes in Swedish Adolescents’ Mental Health During COVID-19 Pandemic

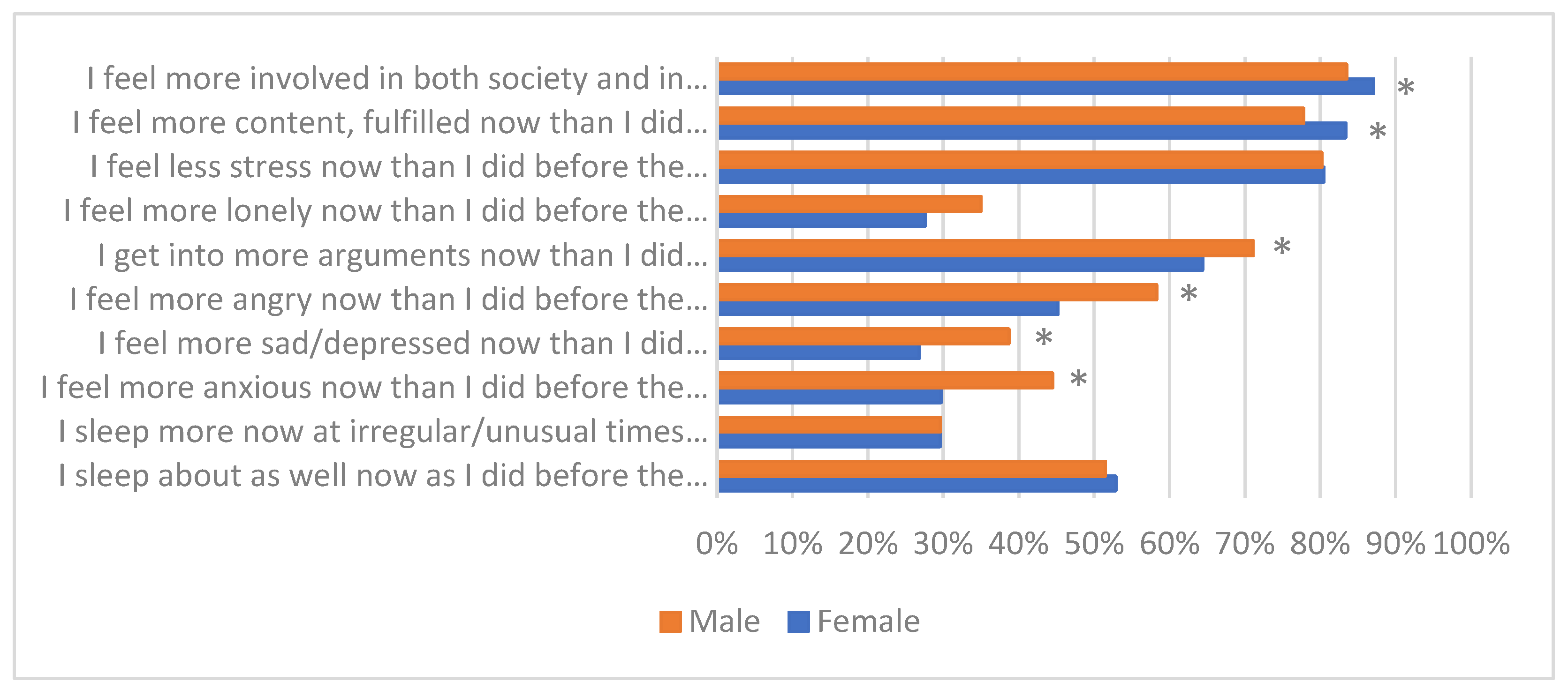

Several significant differences were observed in the proportion of female and male students, indicating negative changes in their mental health during COVID-19 (

Figure 5). A significantly higher proportion of males reported increased anxiety (44% of males, 30% of females,

p=<0.001), increased depression (39% of males, 27% of females,

p=<0.001), increased anger (58% of males, 45% of females,

p=<0.001), increased frequency of conflicts (71% of males, 64% of females, p=0.006), and feelings of loneliness (35% of males, 28% of females,

p=0.002) during COVID-19, compared to before the outbreak. On the other hand, a higher proportion of females reported feeling more content or fulfilled (83% of females, 79% of males,

p=0.043), and being more active in society during the COVID-19 pandemic (87% of females, 84% of males,

p=0.043), compared to before the outbreak (

Figure 5).

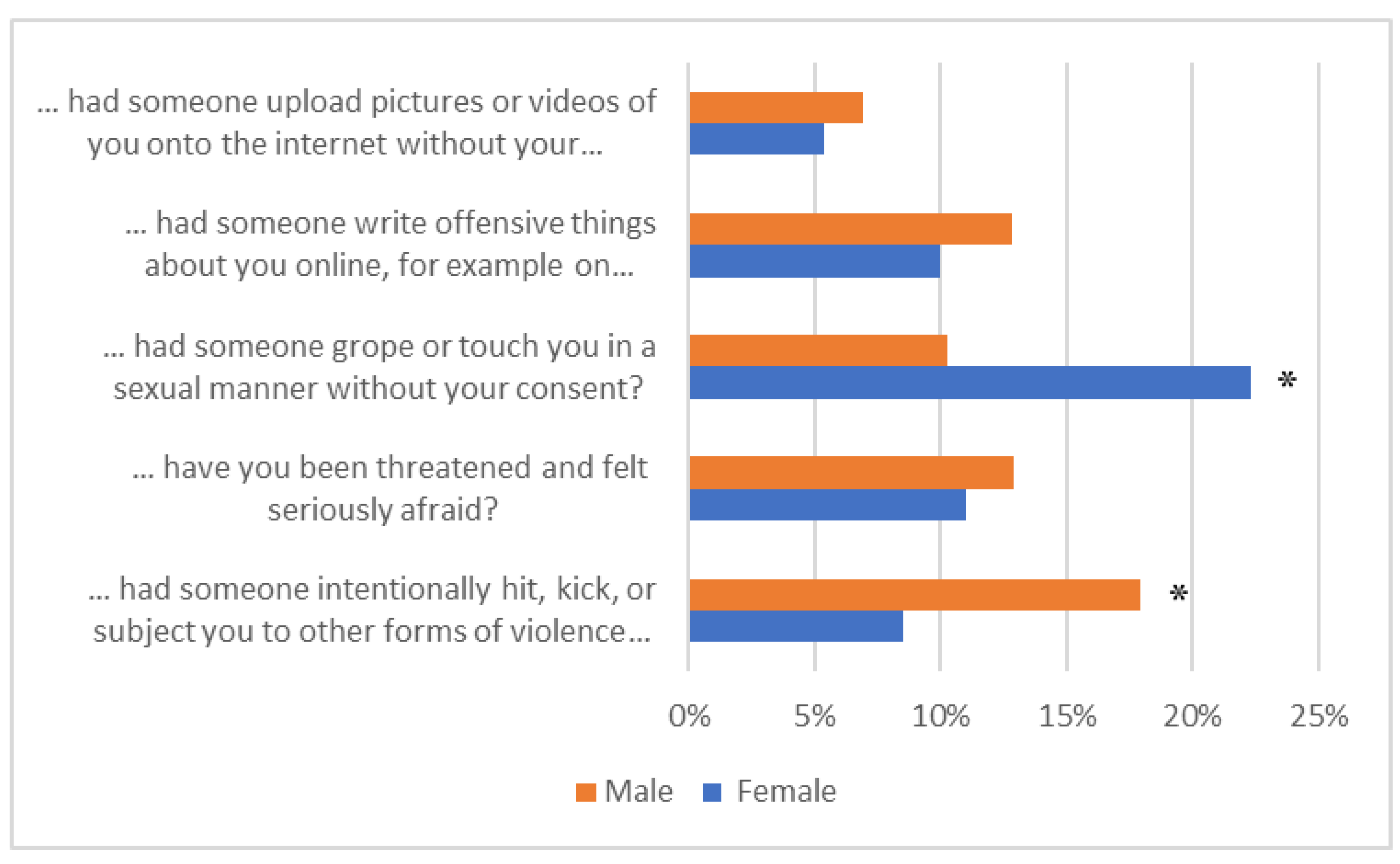

3.4. Changes in Experiencing Victimisation During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Most Swedish adolescents (77%-95% of males and 82%-93% of females) respondents did not experience any form of victimisation during the COVID-19 pandemic. A significantly higher proportion of males than females (18% of males, 9% of females, p=0.001) reported being intentionally hit, kicked, or subjected to other forms of violence that caused injuries but did require them to visit the hospital. On the other hand, a significantly higher proportion of females than males (22% of females, 10% of males, p=0.001) indicated that someone groped or touched them in a sexual manner without their consent (

Figure 6).

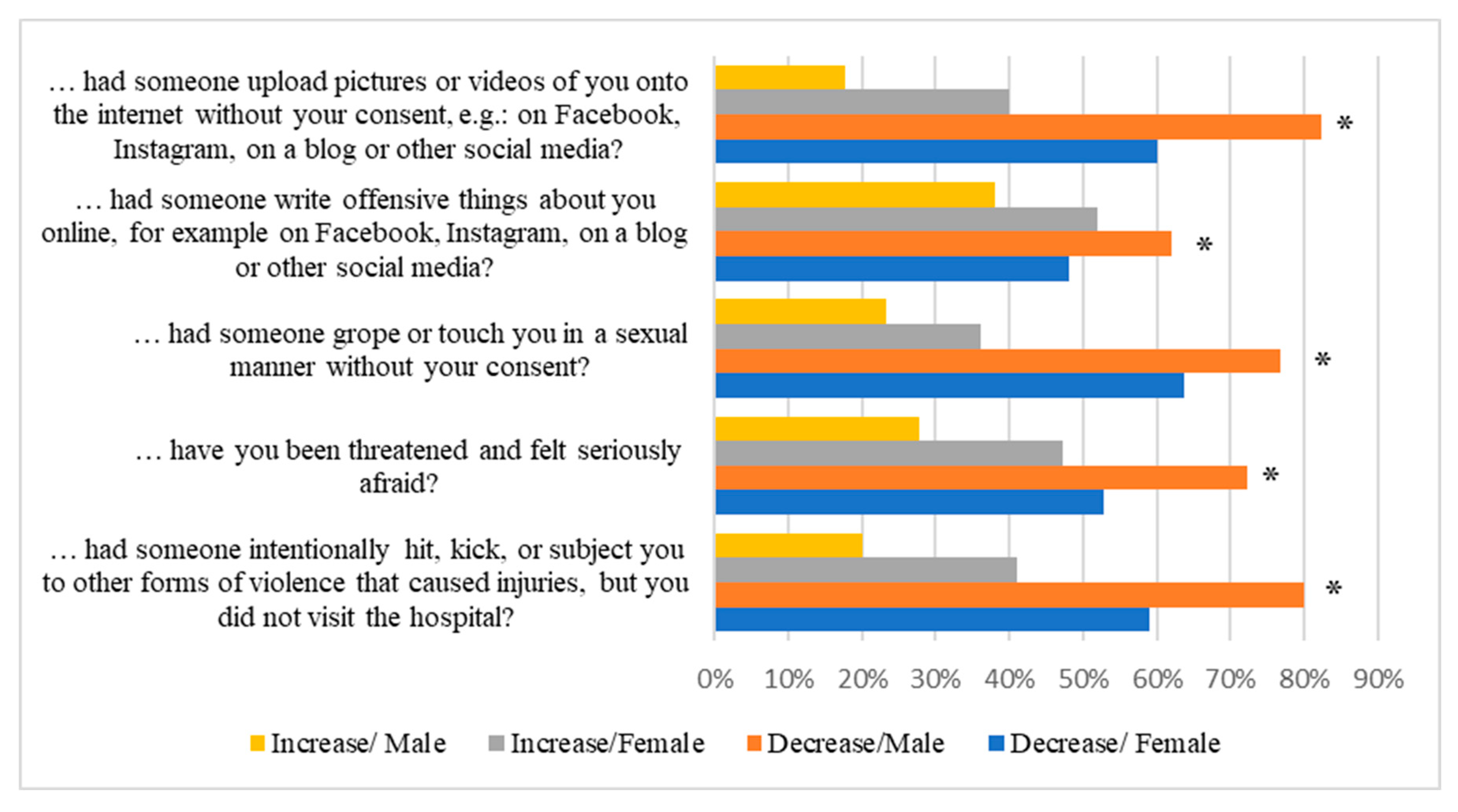

For all items assessing changes in experiencing victimisation during the COVID-19 pandemic, a higher proportion of adolescents reported a decrease rather than an increase in different types of victimisation. There was a significantly higher proportion of males who reported decreased victimisation compared to females (

p ranging between <0.001 and 0.035) (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that the pre-existing salutogenic behaviours exhibited by Swedish adolescents played a significant role in mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on their psychosocial functioning and mental health. It is evident that the majority of participants actively engaged in various life events by maintaining social connections with friends and family, continuing to engage in physical activity, and staying on track with school projects, among other activities. These findings correspond to the research conducted by de Zarate et al. [

26], who explored the association between physical activity, personal social contact, and well-being among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. They observed a positive correlation between physical activity, personal social contact, and the well-being of young individuals. Thus, the salutogenic behaviours mentioned in the present study can be interpreted as protective factors. In a similar vein, Fan et al. [

27] emphasised the significance of employing effective coping strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of the pandemic on daily life.

In this section, the study’s results concerning adolescents’ everyday lives and psychosocial functioning will be discussed in relation to factors supporting health, well-being, and resilience. Moreover, the study's findings pertaining to Swedish adolescents' experiences of mental health, risk behaviour, and victimisation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic will be explored, and gender differences and their implications will also be discussed.

4.1. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Adolescents’ Everyday Lives

The present study reveals that Swedish upper-secondary school students reported a generally low impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their everyday lives. This data file was part of a multinational analysis comparing the impact of COVID-19 across different countries [

24], where it was noted that Swedish adolescents reported a lower impact compared to adolescents from other countries. One possible explanation could be that restrictions in Sweden were less severe than in other countries. Another possible explanation for this phenomenon is that their pre-existing salutogenic behaviours are rooted in positive sociocultural and socioeconomic factors. Such factors may have equipped Swedish adolescents with strong adaptability, contributing to their reports of being less negative impacted of the COVID-19 pandemic than adolescents from other countries. Masten [

28] described how all individuals possess the capacity to adapt, but some exhibit greater resilience due to their positive relationships with family, peers, and even teachers, which act as protective factors. Sweden is a highly developed country with a high standard of living. For example, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [

29] notes that Swedes report higher-than-average life satisfaction and have stronger social networks when compared to the OECD average. This is important to consider, as it paints a picture of a nation of content individuals who can rely on their relationships during challenging times, elucidating why the resilience described by Masten [

28] is more apparent among Swedish youth. Another relevant study that explored psychological resilience among slightly older adolescents (18-24 years) was conducted by Renati et al. [

30] in Italy. Their findings suggest that psychological resilience serves as a mitigating factor for potential emotional disturbances arising from adverse circumstances, such as pandemics.

Interestingly, in a multinational sample, a higher proportion of males, compared to females or non-binary gender students, reported a lower impact of COVID-19 on their lives [

24]. However, in the present Swedish sample, male students reported a significantly higher impact of COVID-19 compared to female students. This finding suggests that the stronger impact on male adolescents in the Swedish context may be attributed to culturally specific gender differences in how adolescents coped and behaved during the first year of the pandemic.

4.2. Changes in Psychosocial Functioning During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Only a small proportion of Swedish adolescents reported a lack of salutogenic approaches in their lives, which partially explains the low impact of the pandemic on their everyday lives, as reported above. Among those who reported changes in suggested salutogenic approaches, a higher proportion indicated a decreased ability to keep up with schoolwork, feel control over their lives, and participate in exercise. However, a higher proportion also reported an increased frequency in engaging activities they didn't have time for before. A similar proportion of both genders reported an increased frequency of participating in outdoor activities, such as taking walks. While slightly more females than males reported feeling more content and active in society during the COVID-19 pandemic, more male adolescents reported increased internet use. Internet usage generally differs between genders, however, as noted by Sun et al. [

31]. Although more male adolescents reported increased internet usage, they may use it in different ways. Males were 57% likelier to use the internet to stay connected with friends through social media or video games, a behaviour that further increased during the pandemic for both genders.

Approximately 80% of both genders increased their online contact with relatives and friends, given the circumstances and restrictions in Sweden that focused on limiting in-person contact. This could be partially viewed as a potentially problematic use of the internet. Orhon et al. [

32] found that problematic internet use among adolescents during the pandemic was associated with poorer sleep quality. Lower psychosocial functioning, such as a lack of physical activity, reduced academic performance, and problematic relationships with parents, were identified as predictors. However, for adolescents, using the internet as a means to stay connected with others was also an important tool to avoid social isolation, maintain social networks, and protect their mental health, as supported by previous studies [

33].

4.3. Adolescents and Family Time during the COVID-19 Pandemic

It is common for young individuals to seek independence and distance themselves from their parents [

34]. However, the COVID-19 restrictions created a situation in which parents and adolescents were confined together at home throughout the day. Interestingly, our findings indicate that this increased family time had a more noticeable impact on female adolescents, leading to an increased frequency of arguments and conflicts.

It is noteworthy that only one-fifth of the female participants in our study reported never having arguments with their parents, whereas almost a third of the male participants reported the same. Despite this difference, both male and female adolescents spent a similar amount of time with their parents, and the proportion of adolescents experiencing changes (either a decrease or an increase in their behaviour) did not differ significantly between genders. These findings suggest that the majority of adolescents in our study had healthy relationships with their parents, which can be considered a protective factor against the impact of the pandemic. This can also be correlated with the findings of Herke et al. [

35], who posit that a favourable familial environment is significantly related to positive health and well-being outcomes among children and adolescents. To further extend the discussion concerning adolescents´ familial experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, the findings show that while females reported significantly more arguments with their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic, they also reported significantly less frequently than males that they had stayed outside without their parents’ knowledge. This suggests that female adolescents are likelier to ask for permission and engage in arguments with their parents, while males tend to act more independently.

In a study by Magson et al. [

14], an increase in conflicts between adolescents and their parents was found to be correlated with a decrease in life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. In line with this, our study revealed that a significantly higher proportion of female students reported a decrease in their sense of control over their daily lives, which may have contributed to a decrease in life satisfaction. This finding aligns with the results of the Moksnes et al. [

36], study, which demonstrated that female adolescents exhibited a stronger negative association between interpersonal and school-related stressors and life satisfaction compared to males. However, it is important to note that throughout the 10-year period of the Moksnes et al. [

36], study, life satisfaction remained consistently at high and stable levels, as measured in three cross-sectional assessments conducted in 2011, 2016, and 2022.

4.4. Changes in Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The present study revealed that more Swedish male adolescents reported an increase in feelings of anxiety, depression, loneliness, and anger, and involvement in conflicts (not limited to conflicts with their parents) compared to their female counterparts. Additionally, we observed that over 80% of those who reported worsened mental health also reported an increase in illicit drug use. This finding is noteworthy because a previous review [

37] and a study focused on the same population [

24] in a multinational context have shown a higher increase in mental health issues among females. In the context of Swedish adolescents, several studies demonstrated that female adolescents reported experiencing poorer mental health outcomes such as headaches, depression, feeling fear, stomach problems, difficulty sleeping, and poor appetite, increased anxiety and worry levels after exposure to COVID-19 compared to male adolescents [

23,

38,

39].

The conflicting findings between these Swedish studies are fascinating yet challenging to explain. One possible explanation could be that the different studies [

38,

39] examined only limited aspects of mental health, focusing on anxiety and various worry themes, as well as depression and somatic complaints [

23]. In contrast, the current study conceptualises mental health in a broader sense, encompassing symptoms of anxiety, depression, loneliness, and anger, and involvement in conflict. This comprehensive approach may distribute the load of negative effects across different factors, potentially leading to a reported decreased intensity compared to when it is expressed solely through one individual concept.

The different findings from studies with multinational samples may be attributed to the unique socio-cultural position of Swedish female adolescents. A previous study on Swedish adolescents’ psychological distress levels indicated that female adolescents exhibited a significantly stronger decrease in mental health in response to negative psychosocial factors within their families compared to male adolescents [

40]. Combined with our finding that more female adolescents reported an increased number of conflicts with their families, while more male students reported decreased mental health as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, this may suggest that changes at the micro-environmental level (such as within the family) may have a stronger impact on females, while changes at the macro-environmental level (such as a pandemic) may more strongly affect males. This underscores the significance of gender-differences in adolescents' ability to cope with their surrounding environment, and possible protective factors, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Top of FormBottom of Form

4.5. Risk Behaviours Before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic

One of the most important findings of the present study is that the majority of Swedish adolescents (93% of females and 87% of males) reported never using illicit drugs. Among the small percentage who used illicit drugs (13% of males and 7% of females), a significant proportion (84% of males and 71% of females) reported changes in the frequency of use. Approximately 60% of those (similar proportion in both genders) who reported changes also reported an increase in illicit drug use, representing almost 7% of males and 3% of females in the study population. The level of substance use (alcohol and drug) and the corresponding changes during the COVID-19 pandemic within the same sample as our study have been extensively examined and quantified using specific measures of alcohol and drug use (AUDIT and DUDIT) in a recent publication by Sfendla et al. [

41].

The increase in drug use among our study population contradicts the information about a general decrease in drug use from another developed country, Spain [

42]. It has been previously noted that adolescent males tend to self-medicate with illicit drugs or alcohol rather than seeking help when facing various mental health issues [

43]. The higher proportion of male adolescents in our study engaging in increased illicit drug use during the COVID-19 pandemic may be both a consequence and a contributing factor to their reported higher rates of worsened mental health, including increased anxiety, depression, sleep problems, and anger. This pattern of increased illicit drug use among males was also observed in the multinational sample [

24]. The significant prevalence of illicit drug use as a way of coping among Swedish adolescents, especially when compared to other countries, highlights the ongoing need for heightened awareness among their social networks, including family and friends as well as various organisations (such as schools, sports clubs, social services, and health services) to effectively recognise and respond to signs of addiction, self-harm, and norm-breaking behaviours even years after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding alcohol use, a similar proportion (about 40%) of female and male adolescents reported never using alcohol, and approximately 50% of both genders reported never getting intoxicated. Both genders, in similar ratios, reported decreasing their alcohol consumption and instances of getting intoxicated more than increasing them. Our finding that about 60% of adolescents used alcohol prior to the pandemic and that its use decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic aligns with a study conducted among Catalan adolescents (14-18 years old) [

42]. A study by Vallentin-Holbech [

44] observed a decline in alcohol consumption among Danish students during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, coinciding with increased restrictions. Decreased alcohol use was attributed to reduced opportunities to purchase alcohol and drink in public spaces, and the absence of social gatherings and parties, where alcohol is typically more accessible. The relatively high proportion of Swedish adolescents consuming alcohol reflects cultural norms and expectations in Western countries [

45].

In our study, males were 43% likelier than females to report engaging in online harassment as perpetrators, although this behaviour was reported by a very small proportion (4%) of the study population. The reported increased time spent on the internet provides more opportunities for harassment, which could explain the corresponding increase in this item. It is possible that females adhere more to gender-appropriate behaviour norms, leading to positive online experiences, while males may have negative experiences [

31]. This could also explain why more male adolescents reported experiencing increased victimisation and harassment online.

4.6. The Frequency of Victimisation before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The majority of Swedish adolescents in our study (ranging from 77% to 95% of males and 82% to 93% of females) reported not experiencing victimisation during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, among those who did report being victimised, a notable gender-specific pattern emerged. Significantly more males reported physical assault, while significantly more females reported sexual assault, aligning with well-documented patterns of victimisation. Westlund and Öberg [

46] highlighted that crimes against another person, including robbery, violence, and sexual offences, are common among youth, additionally aligning with our findings. Additionally, Axell [

47] revealed that young females aged 16-24 are likelier to experience intimate partner violence compared to females over 25 years, with one in five reporting various forms of victimisation by their partner or ex-partner. However, in the context of cyberbullying involving children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, Sorrentino et al. [

48] conducted a systematic review and found an increase in the prevalence of cyberbullying in several Asian countries and Australia, while Western countries experienced a decline. Interestingly, our study indicated a higher proportion of adolescents reporting a decrease rather than an increase of victimisation, with significantly more males reporting a decreased frequency compared to females. This overall decrease in victimisation could potentially be attributed to the increased time spent in online schooling, as previous research has indicated that most crimes against children and adolescents occur within school environments [

49]. Furthermore, our findings suggested that males experienced a greater decrease in all victimisation indicators, possibly indicating that male adolescents are both perpetrators and victims in environments outside of their homes, such as schools, of which they were partly deprived during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Conclusions

Our study provides valuable insights into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychosocial functioning, risk behaviours, and mental health among Swedish adolescents. One notable finding is that the pandemic appears to have had only a modest effect on Swedish upper-secondary school students. Particularly relevant is the higher proportion of male adolescents reporting a deterioration in their mental health as a consequence of the pandemic. Conversely, females demonstrated an increase in several salutogenic behaviours, such as spending time with family and taking part in fun activities and meeting up with friends in real life, while males displayed an increase in negative behaviours, such as engaging in illicit drug use. However, it is important to note that these response patterns were observed for only a limited number of selected questions, where the proportion of respondents represented a small fraction of the overall study population.

6. Practical Implications and Future Research

At the time of writing, it has been over four years since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, a global event that has had a profound impact on the world. It is crucial to carry the learning gained from the experiences of the pandemic into the future. To effectively understand and address the consequences of such events, especially their impact on younger generations, it is essential to build a comprehensive sociocultural database of evidence-based studies in this field.

Our study focuses on a sample of Swedish adolescents, providing insight into how they adapted to the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as their resiliency and ability to cope. Nevertheless, society still needs to be prepared to develop and offer both general and specialised psychological support and care to adolescents. One of the most significant findings of our study was the association between worsened mental health and increased illicit drug use among males. This underscores the importance of early intervention and involvement, particularly by educational institutions, in addressing mental health issues and preventing further deterioration among adolescents. It is crucial to raise awareness about how males express and experience poor mental health to ensure timely support and intervention. Further studies should focus on representative samples of adolescents in Sweden and examine not only the immediate but also the long-term effects of the pandemic, which spanned approximately two years and had a significant impact on various aspects of adolescent development. It is crucial to follow up on the well-being and experiences of individuals who reported worsened mental health, increased victimisation, and increased illicit drug use as a result of the pandemic. Additionally, researchers could explore the support and assistance that Swedish organisations involved with youth could offer in developing effective strategies for addressing the consequences of the pandemic and promoting positive mental health outcomes among adolescents. Ultimately, this study holds significance for policymakers as they deliberate on the potential duration and severity of future restrictions and the resulting consequences. This is particularly relevant due to the fact that Sweden's restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic were relatively more lenient or deviated from those imposed in other countries.

Author Contributions

The project was planned and led by NK, the principal investigator. Conceptualisation was conducted by NK, CJ, MB, and TB. Data collection was performed by BHA, KB, and NK. Methodology development and formal analyses were led by CJ, MB, TB, KB, and NK. The original draft was written and prepared by CJ, BHA, MB, TB, and NK. Visualisation was developed by MB, TB, and KB. These tasks were supervised by NK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project was approved by the Swedish National Ethics Review Board under registration numbers 689-17 and 2020-03351. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration [

50].

Informed Consent Statement

All participating students were provided with clear information stating that their involvement in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Prior to beginning the survey, participants were required to provide their agreement through an electronic informed consent document. Toward the end of the survey, information regarding available resources and links to support organisations was provided to the entire community.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the project leader, Professor Nóra Kerekes, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the young people who took the time to respond to the online questionnaire. Special thanks to Maria Erlandsson and Jan Hovensjö.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Shoshani, A.; Kor, A. The mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents: Risk and protective factors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.N 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher education for the future 2021, 8, 1, 133-141. [CrossRef]

- Lessard, L. M.; Puhl, R. M. Adolescent academic worries amid COVID-19 and perspectives on pandemic-related changes in teacher and peer relations. School Psychology 2021, 36, 5, 285-292. [CrossRef]

- Tasso, A. F.; Hisli Sahin, N.; San Roman, G. J. COVID-19 disruption on college students: Academic and socioemotional implications. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2021, 13, 1, 9. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. Skolbarns hälsovanor I Sverige 2017/18. [Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), results from Sweden of the 2017/18 WHO study] 2018. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/publikationer-och-material/publikationsarkiv/s/skolbarns-halsovanor-i-sverige-2017-2018-grundrapport/.

- Larsen, B.; Luna, B. Adolescence as a neurobiological critical period for the development of higher-order cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2018, 94, 179-195. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R. E. Adolescent brain development: a period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Keynote address. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2004, 1021, 1, 1-22.

- Golberstein, E.; Wen, H.; Miller, B. F. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA pediatrics, 2020, 174, 9, 819-820. [CrossRef]

- de Miranda, D. M.; da Silva Athanasio, B.; Oliveira, A. C. S.; Simoes-e-Silva, A. C. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International journal of disaster risk reduction 2020, 51, 101845. [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.; Russell, S.; Saulle, R.; Croker, H.; Stansfield, C.; Packer, J. ... ; Minozzi, S. School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave: a systematic review. JAMA pediatrics 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J. M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P. L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health 2020, 14, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Moya-Vergara, R.; Portilla-Saavedra, D.; Castillo-Morales, K.; Espinoza-Tapia, R.; Sandoval Pastén, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Mental Health in Adolescents from Northern Chile in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 1, 269. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, L. A.; Debenham, J.; Newton, N. C.; Chapman, C.; Wylie, F. E.; Osman, B.; ...; Champion, K. E. Lifestyle risk behaviours among adolescents: a two-year longitudinal study of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ open 2022, 12, 6, e060309. [CrossRef]

- Magson, N. R.; Freeman, J. Y.; Rapee, R. M.; Richardson, C. E.; Oar, E. L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of youth and adolescence 2021, 50, 44-57. [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, J.; Seto, S.; Fukuda, Y.; Funakoshi, S.; Amae, S.; Onobe, J.; Izumi, S.; Ito, K.; Imamura, F. Mental Health and Physical Activity among Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine 2021, 253, 3, 203–215. [CrossRef]

- Layman, H. M.; Thorisdottir, I. E.; Halldorsdottir, T.; Sigfusdottir, I. D.; Allegrante, J. P.; Kristjansson, A. L. Substance use among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Current psychiatry reports 2022, 24, 6, 307-324. [CrossRef]

- Bäker, N.; Schütz-Wilke, J. Behavioral Changes during the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Comparison of Bullying, Cyberbullying, Externalizing Behavior Problems and Prosocial Behavior in Adolescents. COVID 2023, 3, 2, 289-300. [CrossRef]

- Garthe, R. C.; Kim, S.; Welsh, M.; Wegmann, K.; Klingenberg, J. Cyber-victimization and mental health concerns among middle school students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of youth and adolescence 2023, 52, 4, 840-851. [CrossRef]

- Engel, G. L. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 4286, 129-136.

- Public Health Agency of Sweden (n.d.). https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/folkhalsomyndighetens-roll-under-arbetet-med-covid-19/nar-hande-vad-under-pandemin/. Accessed June 28, 2023.

- Worldometers.info. Sweden COVID - Coronavirus Statistics – Worldometer 2022. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/sweden/.

- Kapetanovic, S.; Gurdal, S.; Ander, B.; Sorbring, E. Reported Changes in Adolescent Psychosocial Functioning during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Adolescents 2021, 1, 1, 10-20. [CrossRef]

- Källmen, H.; Hallgren, M. Mental health problems among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a repeated cross-sectional study from Sweden. Scandinavian journal of public health 2024, 14034948231219832.

- Kerekes, N.; Bador, K.; Sfendla, A.; Belaatar, M.; Mzadi, A. E.; Jovic, V.; ... Zouini, B. Changes in adolescents’ psychosocial functioning and well-being as a consequence of long-term covid-19 restrictions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(16), 8755. [CrossRef]

- The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. 2013. https://bra.se/bra-in-english/home/publications/archive/publications/2014-10-30-crime-statistics-2013.html.

- de Zarate, A. E. R.; Thiel, A.; Sudeck, G.; Dierkes, K.; John, J. M.; Nieß, A. M.; Gawrilow, C. Well-Being of Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Zeitschrift für Psychologie. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Menhas, R.; Laar, R. A. Repercussions of Pandemic and Preventive Measures on General Well-Being, Psychological Health, Physical Fitness, and Health Behavior: Mediating Role of Coping Behavior. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2023, 2437-2454. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S. Ordinary Magic: Lessons from Research or Resilience in Human Development. Education Canada 2010, 49, 3, 28-32. https://www.edcan.ca/wp-content/uploads/EdCan-2009-v49-n3-Masten.pdf.

- The Organisation of Economical Co-operation and Development (n.d). Sweden. https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/sweden/. Accessed June 28, 2023.

- Renati, R.; Bonfiglio, N. S.; Rollo, D. Italian University Students’ Resilience during the COVID-19 Lockdown—A Structural Equation Model about the Relationship between Resilience, Emotion Regulation and Well-Being. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2023, 13, 2, 259-270. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Mao, H.; Yin, C. Male and Female Users’ Differences in Online Technology Community Based on Text Mining. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Orhon, F.; Ergin, A.; Topçu, S.; Çolak, B.; Almiş, H.; Durmaz, N.; ... Başkan, S. The role of social support on the relationships between internet use and sleep problems in adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: a multicentre study. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 2023, 28, 1, 117-123. [CrossRef]

- Deolmi, M.; Pisani, F. Psychological and psychiatric impact of COVID-19 pandemic among children and adolescents. Acta bio-medica: Atenei Parmensis 2020, 91, 4, e2020149. [CrossRef]

- McElhaney, K. B.; Allen, J. P.; Stephenson, J. C.; Hare, A. L. Attachment and autonomy during adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Vol 1. Individual bases of adolescent development 2009 3, 358–403. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Herke, M.; Knöchelmann, A.; Richter, M. Health and well-being of adolescents in different family structures in Germany and the importance of family climate. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17, 18, 6470.

- Moksnes, U. K.; Innstrand, S. T.; Lazarewicz, M.; Espnes, G. A. The Role of Stress Experience and Demographic Factors for Satisfaction with Life in Norwegian Adolescents: Cross-Sectional Trends over a Ten-Year Period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 3, 1940. [CrossRef]

- Bera, L.; Souchon, M.; Ladsous, A.; Colin, V.; Lopez-Castroman, J. Emotional and behavioral impact of the COVID-19 epidemic in adolescents. Current psychiatry reports 2022, 24, 1, 37-46.

- Nyberg, G.; Helgadóttir, B.; Kjellenberg, K.; Ekblom, Ö. COVID-19 and unfavorable changes in mental health unrelated to changes in physical activity, sedentary time, and health behaviors among Swedish adolescents: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Hagquist, C. Worry and Psychosomatic Problems Among Adolescents in Sweden in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Unequal Patterns Among Sociodemographic Groups?. Journal of Adolescent Health 2023, 72, 5, 688-695. [CrossRef]

- Kerekes, N.; Zouini, B.; Tingberg, S.; Erlandsson, S. Psychological Distress, Somatic Complaints, and Their Relation to Negative Psychosocial Factors in a Sample of Swedish High School Students. Frontiers in public health 2021, 9, 669958. [CrossRef]

- Sfendla, A.; Bador, K.; Paganelli, M.; Kerekes, N. Swedish High School Students' Drug and Alcohol Use Habits throughout 2020. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19, 24, 16928. [CrossRef]

- Rogés, J.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Colom, J.; Folch, C.; Barón-Garcia, T.; González-Casals, H.; Fernández, E.; Espelt, A. Consumption of Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco in a Cohort of Adolescents before and during COVID-19 Confinement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 15, 7849. [CrossRef]

- Tiburcio, N. J.; Baker, S. L.; Kimmell, K. S. Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Co-Morbidities Among Teens in Treatment: SASSI-A3 Correlations in Screening Scores. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences 2021, 10, 1, 10-17. http://. [CrossRef]

- Vallentin-Holbech, L.; Ewing, S. W. F.; Thomsen, K. R. Hazardous alcohol use among Danish adolescents during the second wave of COVID-19: Link between alcohol use and social life. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sudhinaraset, M.; Wigglesworth, C.; Takeuchi, D. T. Social and Cultural Contexts of Alcohol Use. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews 2016, 38(1), 35–45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4872611/.

- Westlund, O.; Öberg, J. Strategiska brott bland ungdomar på 2010-talet - och faktorer av betydelse för att leva ett kriminellt liv. [Strategic crimes among young people in the 2010s - and factors of importance for living a criminal life] (2021:5) 2021. https://bra.se/download/18.1f8c9903175f8b2aa7087f9/1618295581817/2021_5_Strategiska_brott.pdf.

- Axell, S. Kortanalys 6/8: Brott i nära relationer bland unga. [Short analysis 6/8: Crimes in close relationships among young people.]2018.https://bra.se/download/18.c4ecee2162e20d258c4a9ea/1553612799682/2018_Brott_i_nara_relationer_bland_unga.pdfland unga (bra.se).

- Sorrentino, A.; Sulla, F.; Santamato, M.; di Furia, M.; Toto, G. A.; Monacis, L. Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization Prevalence among Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 10, 5825. [CrossRef]

- Westberg, S. Skolundersökning om brott 2019: Om utsatthet och delaktighet i brott. [School survey on crime 2019: About vulnerability and participation in crime.] (2020:11). 2020. https://bra.se/download/18.7d27ebd916ea64de5306dead/1606817015507/2020_11_Skolundersokningen_om_brott_2019.pdf.

- WMA. Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principal för Medical Reseaech. Adopted by the 18th WMA General Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, June 1964 and amended by the: 64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).