Submitted:

28 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Delayed Retirement Policy Affects the Sustainability of Pension Funds through Pension System Adjustments

2.2. Delayed Retirement Policies Affect the Sustainability of Pension Funds by Changing the Structure of the Labor Market

2.3. Delayed Retirement Policies Affect the Sustainability of Pension Funds by Changing Fertility Rates

3. Construction of Theoretical Model

3.1. Pension Fund Income Modeling

3.1.1. Model of Income from Pension Insurance Benefits in Social Integration Accounts

3.1.2. Individual Account Pension Income Model

3.1.3. Financial Subsidies

3.2. Model of Social Pension Expenditure

3.3. Urban Workers' Basic Pension Insurance Pension Revenue and Expenditure Gap Measurement Model

3.3.1. Current Urban Workers' Basic Pension Insurance Pension Income and Expenditure Gap

3.3.2. Accumulated Balance of Urban Workers' Basic Pension Insurance Pensions

4. Parameter Setting and Data Selection Parameter Setting and Data Selection

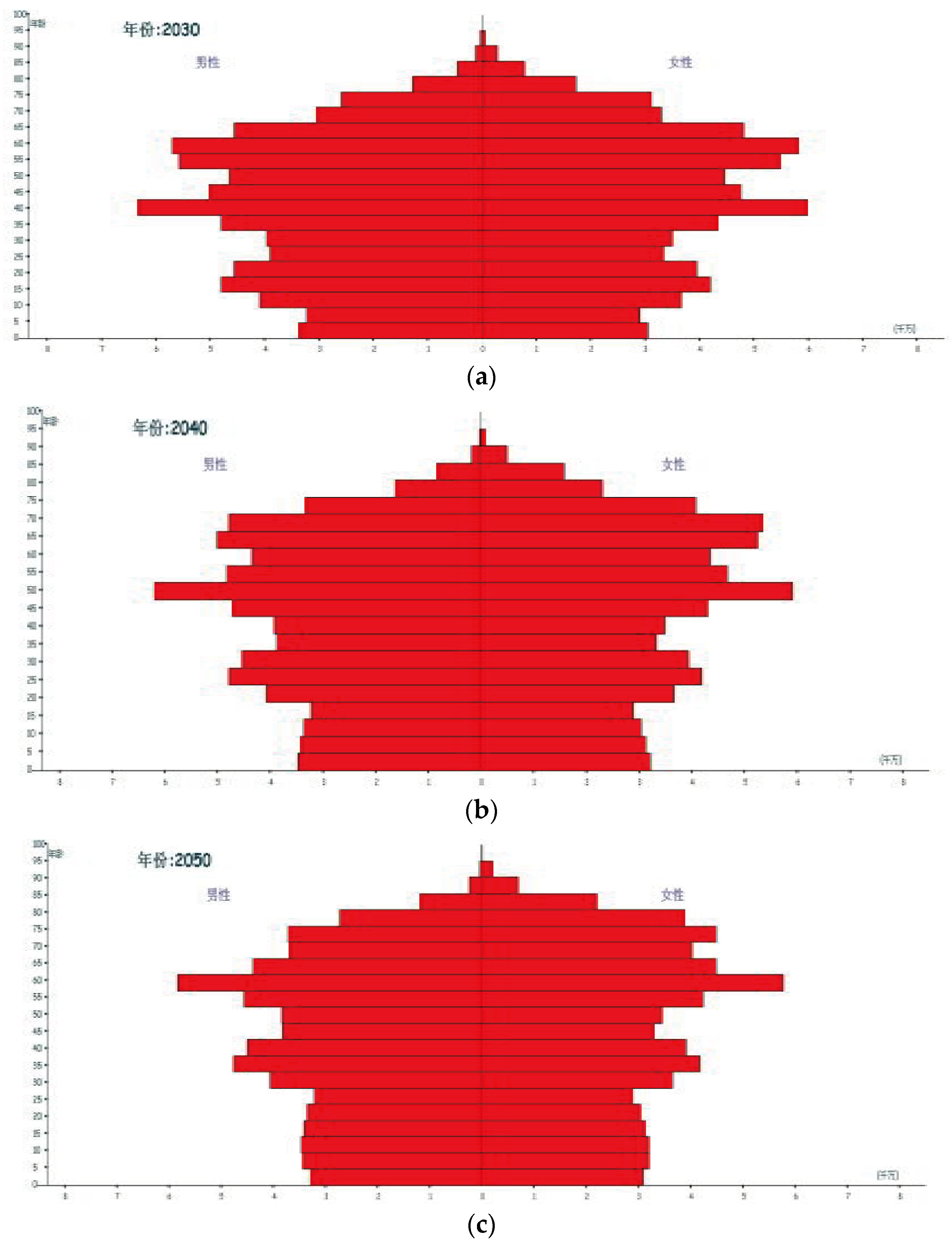

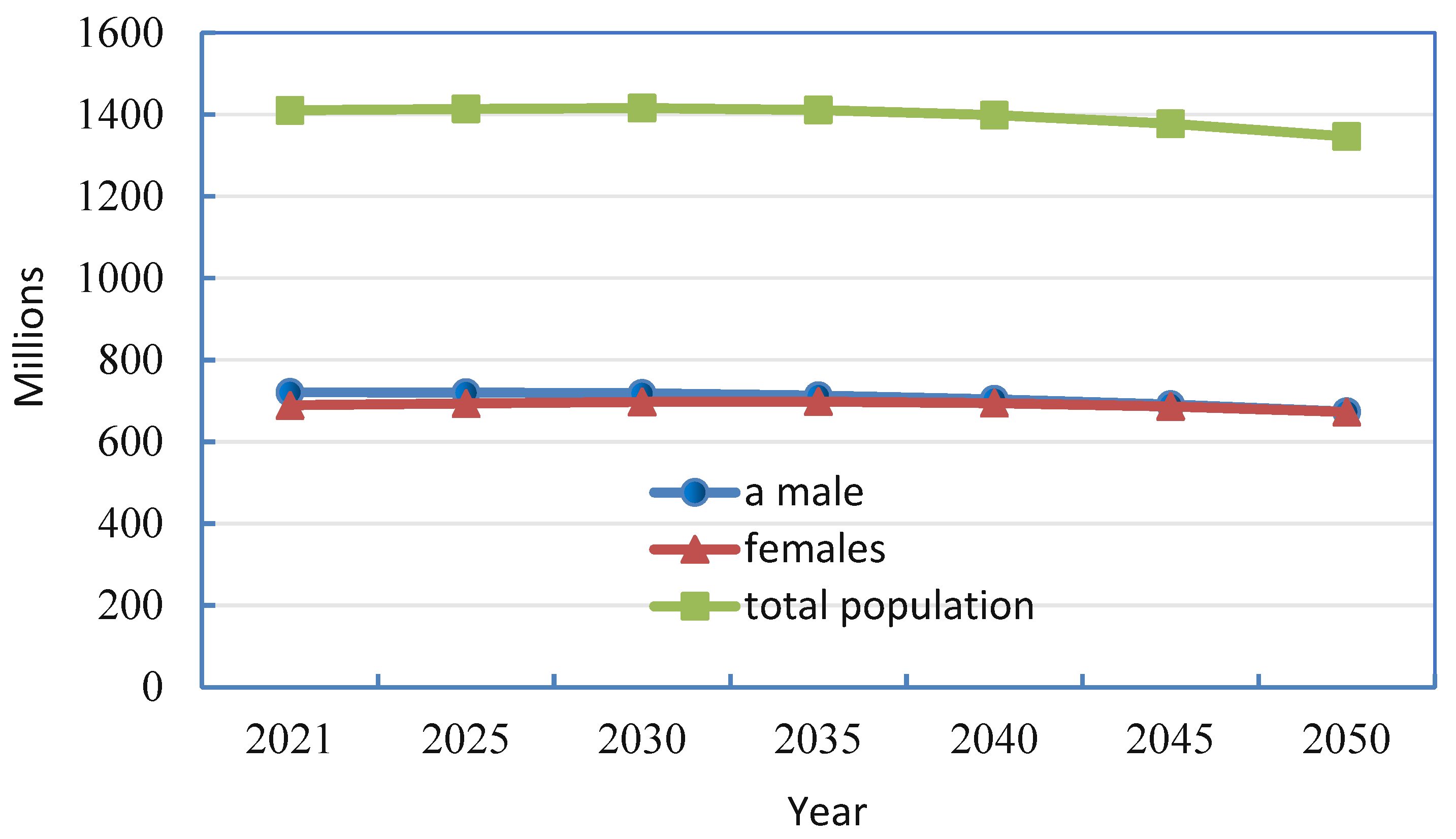

4.1. Total Population and Population by Sex

4.2. Working Age and Retirement Age

4.3. Maximum Age of Survival

4.4. Average Annual Wage Growth Rate

4.5. Population Urbanization Rate

4.6. Employment Rate of the Urban Population

4.7. Compliance Rate for Basic Pension Insurance for Urban Workers

4.8. Contribution Rate for Basic Pension Insurance for Urban Workers

4.9. Pension Replacement Rate

4.10. Pension Adjustment Rate

4.11. Pension Crediting Rate

4.12. Average Social Wage

4.13. Government Financial Subsidies as a Proportion of Urban Workers' Basic Pension Income

5. Calculation Results and the Analysis

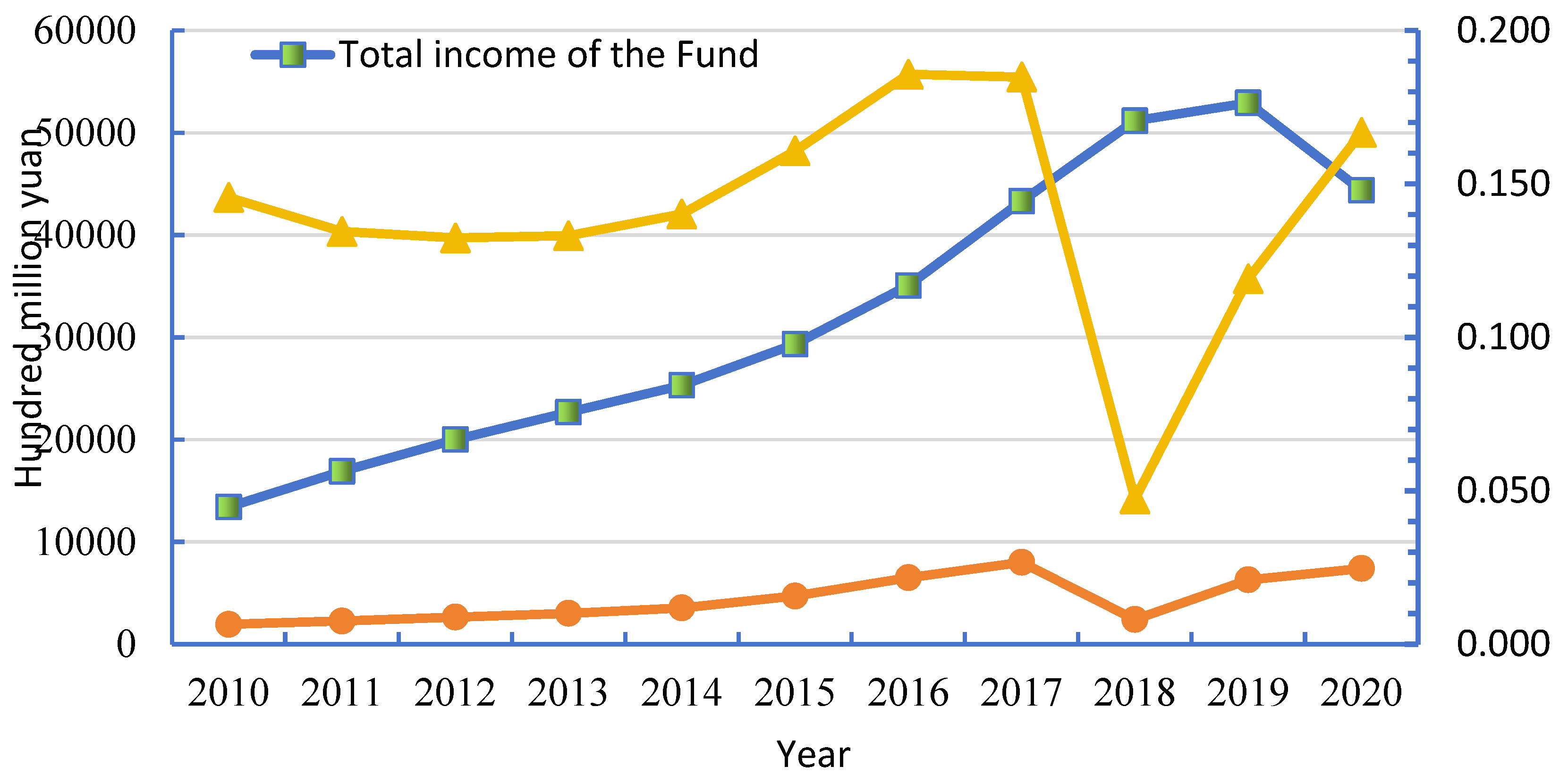

5.1. Results and Analysis of the Forecast of Income and Expenditure of the Urban Workers' Pension Insurance Fund

5.2. Analysis of the Effect of Delayed Retirement on Pension Sustainability

5.2.1. Delayed Retirement Program Design

5.2.2. Impact of Delayed Retirement on Pension Sustainability

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Huang, J.; Liu, J. External support for elderly care social enterprises in China: A government-society-family framework of analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 8244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Mi, H. Evaluation on the sustainability of urban public pension system in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Edwards, R. The fiscal effects of population aging in the US: Assessing the uncertainties. Tax Policy and the Economy 2002, 16, 141–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecchenino, R.A.; Pollard, P.S. The effects of annuities, bequests, and aging in an overlapping generations model of endogenous growth. The Economic Journal 1997, 107, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; et al. The new fertility policy and the actuarial balance of China urban employee basic endowment insurance fund based on stochastic mortality model. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhao, X. Stochastic forecast of the financial sustainability of basic pension in China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A.; Berkel, B. Pension reform in Germany: The impact on retirement decisions. Finanz Archiv/Public Finance Analysis 2004, 60, 393–421. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9913. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Stauvermann, P.J.; Sun, J. The impact of the two-child policy on the pension shortfall in China: A case study of Anhui province. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, C.; Yi, M. The optimal choice of delayed retirement policy in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecki, M.; Goraus, K.; Hagemejer, J.; et al. Decreasing fertility vs increasing longevity: Raising the retirement age in the context of ageing processes. Economic Modelling 2016, 52, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, E.; Ludwig, A.; Börsch-Supan, A. Aging and pension reform: Extending the retirement age and human capital formation. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 2017, 16, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.H. The welfare effects of pension reforms in an aging economy. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management 2017, 7, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yang, J. Does delayed retirement crowd out workforce welfare? Evidence in China. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.H.; Zhai, S.; Zhou, M. Research on the accumulation effect of pension income and payments caused by progressive retirement age postponement policy in China. Journal of aging & social policy 2019, 31, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, J.; Yang, Q. Assessing the financial sustainability of the pension plan in China: The role of fertility policy adjustment and retirement delay. Sustainability 2019, 11, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalive, R.; Magesan, A.; Staubli, S. How social security reform affects retirement and pension claiming. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2023, 15, 115–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A.H.; Berkel, B. Pension reform in Germany: The impact on retirement decisions. Finanz Archiv / Public Finance Analysis 2004, 60, 393–421. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9913. [CrossRef]

- Bratun, U.; Zurc, J. The motives of people who delay retirement: An occupational perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 2022, 29, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levanon, G.; Cheng, B. US workers delaying retirement: Who and why and implications for businesses. Business Economics 2011, 46, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, A.G. The case for raising social security’s early retirement age. Retirement Policy Outlook 2010, 3, 1. http://www.aei.org/.

- Hu, J.; Stauvermann, P.J.; Nepal, S.; Zhou, Y. Can the policy of increasing retirement age raise pension revenue in China—A case study of Anhui province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhong, S.; Qi, T. Delaying retirement and China’s pension payment dilemma: Based on a general analysis framework. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 126559–126572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Truesdale, B.C. Working longer and population aging in the US: Why delayed retirement isn’t a practical solution for many. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2023, 24, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkarnain, A.; Rutledge, M.S. How does delayed retirement affect mortality and health? Center for retirement research at Boston College, CRR WP 2018, 11. http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108178. [CrossRef]

- König, S.; Lindwall, M.; Johansson, B. Involuntary and delayed retirement as a possible health risk for lower educated retirees. Journal of Population Ageing 2019, 12, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Fan, H.; Liu, X.; Ma, C. Delayed retirement policy and unemployment rates. Journal of Macroeconomics 2022, 71, 103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnell, A.H.; Wu, A.Y. Will delayed retirement by the baby boomers lead to higher unemployment among younger workers? Boston College Center for Retirement Research Working Paper. 2012-22. http://crr.bc.edu.

- Burtless, G. The impact of population aging and delayed retirement on workforce productivity. Available at SSRN. 2013, 2275023. http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104764.

- Oyaro Gekara, V.; Snell, D.; Chhetri, P. Are older workers ‘crowding out’ the young? A study of the Australian transport and logistics labour market. Labour & Industry: a Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 2015, 25, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, H.; Pestieau, P. The double dividend of postponing retirement. International Tax and Public Finance 2003, 10, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laun, T.; Wallenius, J. A life cycle model of health and retirement: The case of Swedish pension reform. Journal of Public Economics 2015, 127, 127–136. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/56215. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Shen, Z. Delaying retirement, the burden of working population, subjective well being. Journal of Guizhou University of Finance and Economics 2020, 38, 69. https://gcxb.gufe.edu.cn/EN/Y2020/V38/I04/69.

- Boado-Penas, M.C.; Eisenberg, J.; Korn, R. Transforming public pensions: A mixed scheme with a credit granted by the state. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 2021, 96, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, F.; et al. Projecting sex imbalances at birth at global, regional and national levels from 2021 to 2100: Scenario-based bayesian probabilistic projections of the sex ratio at birth and missing female births based on 3.26 billion birth records. BMJ Global Health 2021, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Jing, Z.; Cheng, J.; et al. National and provincial population projected to 2100 under the shared socioeconomic pathways in China. Advances in Climate Change Research 2017, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, Z. Stochastically assessing the financial sustainability of individual accounts in the urban enterprise employees’pension plan in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, Z. Forecast and analysis of national GDP in China based on Arima model. Academic Journal of Science and Technology 2022, 3, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Guan, W.; Liu, H. Chinese urbanization 2050: SD modeling and process simulation. Science China Earth Sciences 2017, 60, 1067–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lv, H.; et al. The new fertility policy and the actuarial balance of China urban employee basic endowment insurance fund based on stochastic mortality model. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zeng, Y. Retirement age, fertility policy and the sustainability of China’s basic pension insurance fund. Finance Research 2015, 41, 46–57+69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bai, M.; Feng, P.; Zhu, M. Stochastic assessments of urban employees’ pension plan of China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.C.; Lugauer, S.; Mark, N.C. Demographics and aggregate household saving in Japan, China and India. J. Macroecon. 2017, 51, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| particular year | Levy income | financial subsidy | Pension income | Pension expenditure | Current income and expenditure | Cumulative balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 67684.52 | 11100.86 | 78785.38 | 74483.33 | 4302.05 | 52619.05 |

| 2022 | 73098.53 | 11988.81 | 85087.34 | 83155.23 | 1932.11 | 54551.16 |

| 2023 | 78447.86 | 12866.14 | 91314.00 | 93721.76 | -2407.76 | 52143.40 |

| 2024 | 84202.00 | 13809.87 | 98011.88 | 105533.92 | -7522.04 | 44621.36 |

| 2025 | 90621.32 | 14862.70 | 105484.02 | 118289.79 | -12805.78 | 31815.58 |

| 2026 | 96839.13 | 15882.47 | 112721.61 | 132239.11 | -19517.50 | 12298.08 |

| 2027 | 103745.24 | 17015.14 | 120760.38 | 146024.54 | -25264.16 | -12966.07 |

| 2028 | 111212.13 | 18239.77 | 129451.90 | 161089.26 | -31637.36 | -44603.43 |

| 2029 | 119111.65 | 19535.36 | 138647.02 | 177893.78 | -39246.76 | -83850.19 |

| 2030 | 127624.15 | 20931.49 | 148555.64 | 196054.06 | -47498.43 | -131348.62 |

| 2031 | 135851.90 | 22280.91 | 158132.81 | 215453.02 | -57320.21 | -188668.83 |

| 2032 | 144800.08 | 23748.49 | 168548.57 | 235219.12 | -66670.55 | -255339.38 |

| 2033 | 154370.53 | 25318.13 | 179688.66 | 256459.68 | -76771.02 | -332110.40 |

| 2034 | 164712.63 | 27014.33 | 191726.96 | 278772.70 | -87045.74 | -419156.14 |

| 2035 | 175751.27 | 28824.76 | 204576.03 | 302271.35 | -97695.32 | -516851.46 |

| 2036 | 185797.92 | 30472.50 | 216270.42 | 327498.29 | -111227.87 | -628079.33 |

| 2037 | 196411.85 | 32213.28 | 228625.13 | 352134.37 | -123509.23 | -751588.57 |

| 2038 | 207211.53 | 33984.52 | 241196.06 | 378244.60 | -137048.55 | -888637.11 |

| 2039 | 217812.47 | 35723.17 | 253535.64 | 406079.49 | -152543.85 | -1041180.96 |

| 2040 | 228244.31 | 37434.09 | 265678.39 | 435721.20 | -170042.80 | -1211223.77 |

| 2041 | 236411.52 | 38773.58 | 275185.10 | 466587.41 | -191402.31 | -1402626.08 |

| 2042 | 244924.54 | 40169.79 | 285094.33 | 493779.98 | -208685.66 | -1611311.74 |

| 2043 | 253917.11 | 41644.65 | 295561.76 | 521579.91 | -226018.14 | -1837329.88 |

| 2044 | 263550.18 | 43224.56 | 306774.74 | 549671.96 | -242897.23 | -2080227.11 |

| 2045 | 273554.41 | 44865.34 | 318419.75 | 578712.82 | -260293.07 | -2340520.17 |

| 2046 | 281322.76 | 46139.42 | 327462.18 | 609126.28 | -281664.10 | -2622184.27 |

| 2047 | 288729.71 | 47354.23 | 336083.93 | 636392.76 | -300308.82 | -2922493.09 |

| 2048 | 296219.03 | 48582.54 | 344801.57 | 664598.74 | -319797.17 | -3242290.27 |

| 2049 | 304112.74 | 49877.18 | 353989.92 | 693085.36 | -339095.45 | -3581385.72 |

| 2050 | 310013.49 | 50844.96 | 360858.45 | 718122.17 | -357263.72 | -3938649.43 |

| particular year | Pre-delayed retirement | Post-delayed retirement | particular year | Pre-delayed retirement | Post-delayed retirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 78785.38 | 78785.38 | 2036 | 216270.42 | 233077.76 |

| 2022 | 85087.34 | 85087.34 | 2037 | 228625.13 | 248565.41 |

| 2023 | 91314.00 | 91947.71 | 2038 | 241196.06 | 264813.88 |

| 2024 | 98011.88 | 99361.95 | 2039 | 253535.64 | 281134.45 |

| 2025 | 105484.02 | 107573.56 | 2040 | 265678.39 | 297670.74 |

| 2026 | 112721.61 | 115591.01 | 2041 | 275185.10 | 311394.51 |

| 2027 | 120760.38 | 124421.06 | 2042 | 285094.33 | 325057.23 |

| 2028 | 129451.90 | 134045.13 | 2043 | 295561.76 | 341254.67 |

| 2029 | 138647.02 | 143641.04 | 2044 | 306774.74 | 358864.32 |

| 2030 | 148555.64 | 155516.11 | 2045 | 318419.75 | 377325.02 |

| 2031 | 158132.81 | 166427.67 | 2046 | 327462.18 | 393160.74 |

| 2032 | 168548.57 | 176885.12 | 2047 | 336083.93 | 409524.73 |

| 2033 | 179688.66 | 189939.73 | 2048 | 344801.57 | 426536.11 |

| 2034 | 191726.96 | 203934.83 | 2049 | 353989.92 | 444281.19 |

| 2035 | 204576.03 | 218958.40 | 2050 | 360858.45 | 458944.02 |

| particular year | Pre-delayed retirement | Post-delayed retirement | particular year | Pre-delayed retirement | Post-delayed retirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 74483.33 | 74483.33 | 2036 | 327498.29 | 290452.05 |

| 2022 | 83155.23 | 83155.23 | 2037 | 352134.37 | 308182.60 |

| 2023 | 93721.76 | 92356.04 | 2038 | 378244.60 | 326186.90 |

| 2024 | 105533.92 | 102624.31 | 2039 | 406079.49 | 345247.01 |

| 2025 | 118289.79 | 113786.54 | 2040 | 435721.20 | 365204.60 |

| 2026 | 132239.11 | 126003.12 | 2041 | 466587.41 | 385934.77 |

| 2027 | 146024.54 | 138068.88 | 2042 | 493779.98 | 404766.84 |

| 2028 | 161089.26 | 151106.93 | 2043 | 521579.91 | 419803.78 |

| 2029 | 177893.78 | 165474.95 | 2044 | 549671.96 | 433647.91 |

| 2030 | 196054.06 | 180927.06 | 2045 | 578712.82 | 447507.53 |

| 2031 | 215453.02 | 197324.39 | 2046 | 609126.28 | 461517.18 |

| 2032 | 235219.12 | 216999.38 | 2047 | 636392.76 | 471388.68 |

| 2033 | 256459.68 | 234055.70 | 2048 | 664598.74 | 480960.57 |

| 2034 | 278772.70 | 252092.08 | 2049 | 693085.36 | 490222.27 |

| 2035 | 302271.35 | 270838.30 | 2050 | 718122.17 | 497747.10 |

| particular year | Pre-delayed retirement | Post-delayed retirement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference between current income and expenditure | Cumulative balance | Current income and expenditure | Cumulative balance | |

| 2021 | 4302.05 | 52619.05 | 4302.05 | 52619.05 |

| 2022 | 1932.11 | 54551.16 | 1932.11 | 54551.16 |

| 2023 | -2407.76 | 52143.40 | -408.33 | 54142.83 |

| 2024 | -7522.04 | 44621.36 | -3262.36 | 50880.47 |

| 2025 | -12805.78 | 31815.58 | -6212.98 | 44667.49 |

| 2026 | -19517.50 | 12298.08 | -10412.11 | 34255.38 |

| 2027 | -25264.16 | -12966.07 | -13647.81 | 20607.57 |

| 2028 | -31637.36 | -44603.43 | -17,061.80 | 3545.77 |

| 2029 | -39246.76 | -83850.19 | -21833.91 | -18288.15 |

| 2030 | -47498.43 | -131348.62 | -25410.94 | -43699.09 |

| 2031 | -57320.21 | -188668.83 | -30896.72 | -74595.81 |

| 2032 | -66670.55 | -255339.38 | -40114.25 | -114710.07 |

| 2033 | -76771.02 | -332110.40 | -44115.97 | -158826.04 |

| 2034 | -87045.74 | -419156.14 | -48157.26 | -206983.29 |

| 2035 | -97695.32 | -516851.46 | -51879.89 | -258863.19 |

| 2036 | -111227.87 | -628079.33 | -57374.29 | -316237.48 |

| 2037 | -123509.23 | -751588.57 | -59617.18 | -375854.66 |

| 2038 | -137048.55 | -888637.11 | -61373.02 | -437227.68 |

| 2039 | -152543.85 | -1041180.96 | -64112.56 | -501340.24 |

| 2040 | -170042.80 | -1211223.77 | -67533.86 | -568874.09 |

| 2041 | -191402.31 | -1402626.08 | -74540.26 | -643414.35 |

| 2042 | -208685.66 | -1611311.74 | -79709.61 | -723123.96 |

| 2043 | -226018.14 | -1837329.88 | -78549.11 | -801673.07 |

| 2044 | -242897.23 | -2080227.11 | -74783.59 | -876456.65 |

| 2045 | -260293.07 | -2340520.17 | -70182.51 | -946639.16 |

| 2046 | -281664.10 | -2622184.27 | -68356.44 | -1014995.61 |

| 2047 | -300308.82 | -2922493.09 | -61863.95 | -1076859.56 |

| 2048 | -319797.17 | -3242290.27 | -54424.45 | -1131284.01 |

| 2049 | -339095.45 | -3581385.72 | -45941.08 | -1177225.09 |

| 2050 | -357263.72 | -3938649.43 | -38803.08 | -1216028.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).