Submitted:

29 March 2024

Posted:

02 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

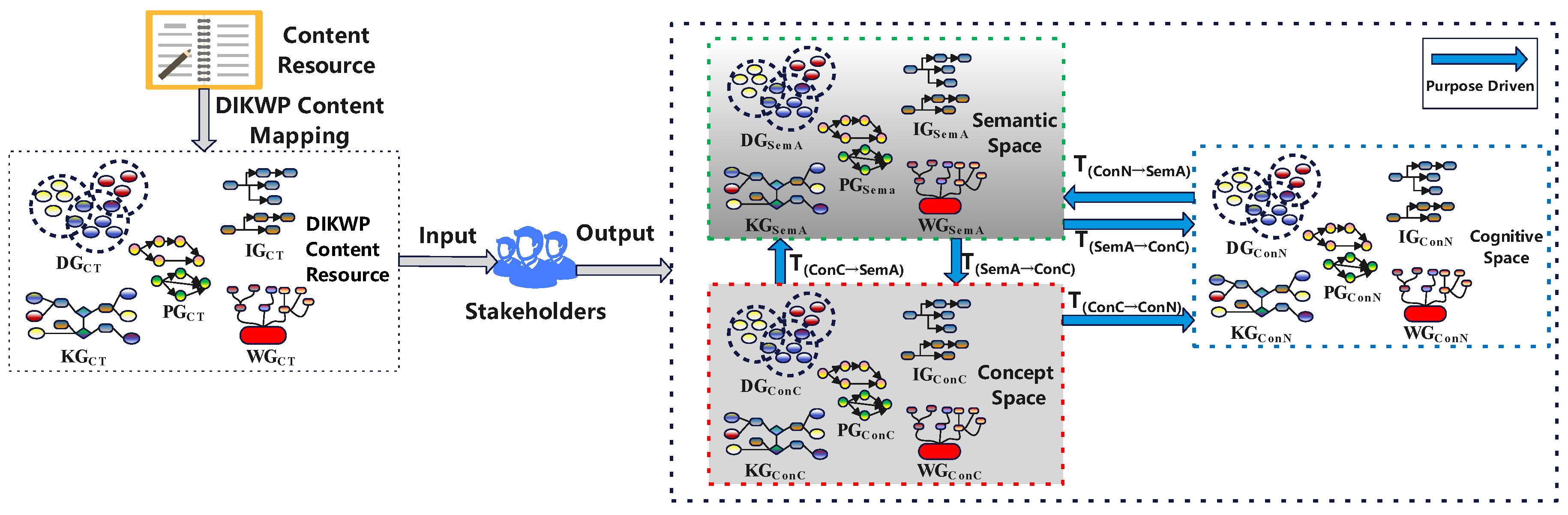

- Concept Space provides us with a framework for understanding and organizing the relationship between regulatory requirements and business practices. By mapping key concepts and their interactions, it reveals the possibilities and challenges of compliance pathways;

- Cognitive Space focuses on cognitive activities in the decision-making process, including how to identify, process, and utilize information to form knowledge, wisdom, and purpose, to support compliance and business decisions;

- Semantic Space emphasizes the relationships between semantic units, including the associations and dependencies among vocabulary, regulations, and concepts, thereby ensuring the accurate transmission and interpretation of information and knowledge.

- Innovative application of the DIKWP model: Our study innovatively applies the DIKWP model to analyze and address the complexity involved in HFT and its regulation. This approach enables a nuanced understanding of the regulatory challenges and operational uncertainties faced by HFT companies, providing a structured framework for addressing these issues;

- Addressing uncertainty in HFT regulations: We analyzed the inherent uncertainty in regulations affecting HFT practices during the early stages of the Dodd-Frank Act. By dissecting issues related to vague definitions, regulatory requirements, interpretational differences, and lack of detailed descriptions, this research offers clear insights for more effectively managing regulatory compliance;

- Elaboration on Concept, Cognitive, and Semantic Spaces: We provide detailed explanations and a set of definitions and analytical methods for Concept Space, Cognitive Space, and Semantic Space within the context of the DIKWP model. This enhances understanding of how HFT companies interpret, adapt to regulatory requirements, and formulate strategies around regulatory demands, thereby leveraging these spaces to improve operational coordination and decision-making.

2. Problem Description

2.1. Uncertainty in Market Conditions

2.1.1. Political Factors

- Geopolitical tensions (): Geopolitical tensions, such as sudden outbreaks of conflict, wars, or sanctions, typically lead to fluctuations in global stock markets. These fluctuations not only impact global markets but also have a particular influence on companies or industries with significant interests in regions of geopolitical tension. For instance, during a political crisis in 2014, concerns over escalating tensions between Country A and Country B led to turmoil in the global energy markets. Country A is one of the world’s largest natural gas suppliers, and any threat to its supply capacity could result in energy price volatility. During this period, stocks related to the energy sector, especially European energy companies reliant on Country A’s energy supplies, may experience price fluctuations. HFT may exploit this volatility by swiftly buying and selling energy stocks to generate profits, while closely monitoring any further political developments that could affect energy supply and prices.

- Policy changes (): Changes in government or international organizations’ policies, such as adjustments to trade policies or monetary policies, can significantly impact economic activities and the profitability of multinational corporations. For example, in 2018, Country D’s imposition of tariffs on goods from Country C intensified global trade tensions, leading to profound effects on global stock markets, commodity markets, and currency markets. High-frequency traders may analyze the impact of such policy changes on different markets and assets, adjusting stock trading strategies swiftly in the short term to capture price fluctuations and generate profits.

2.1.2. Market Sentiment

- Market overreaction (): Market participants may overreact to certain news or events, leading to sharp short-term fluctuations in asset prices that may be unrelated to fundamentals. For example, if the CEO of a large technology company suddenly announces resignation, even though the long-term impact of this resignation on the company’s fundamentals may be limited, the stock price may experience a significant decline in the short term due to market sentiment. High-frequency traders can profit from these short-term price fluctuations by capturing them swiftly after the news is announced, trading based on anticipated systematic model expectations.

- Unconfirmed news (): Unconfirmed news or rumors spread on social media and news websites can quickly alter market sentiment, causing short-term fluctuations in the prices of certain assets. For instance, if rumors about the imminent acquisition of a listed company circulate online, even though this news is unconfirmed, the company’s stock price may temporarily rise due to investors buying in. High-frequency traders may capitalize on these short-term price movements for trading, but they also face high risks because once the news is confirmed to be false, the stock price may quickly fall back, indicating precise control over risk assessment is required.

- Herd behavior (): Investors may mimic the behavior of other investors rather than make investment decisions based on their analysis, leading to herd behavior in the market, and exacerbating asset price fluctuations. For example, when a particular stock or industry suddenly becomes favored by the market, a large number of investors may follow suit and buy-in, driving up prices. However, this price increase is often not supported by the fundamentals of the company. Once the trend reverses, followers may rush to sell their stocks, causing prices to plummet sharply. High-frequency traders can identify the formation and reversal of such trends through algorithms, thus swiftly entering and exiting the market when market sentiment changes, capturing profits.

2.1.3. Counterparty

- Competitors executing similar strategies (): When multiple participants in the market simultaneously execute similar trading strategies, competition may lead to diminishing profit margins. If multiple high-frequency traders are exploiting the same arbitrage strategy, such as a rapid response strategy based on certain economic indicators, arbitrage opportunities in the market may quickly disappear, as the first participant to execute the trade captures the profit, leaving subsequent participants finding the market adjusted without the expected profit space.

- Opposing strategy opponents (): Other traders may be executing strategies that are entirely opposed to yours, which may directly impact your trading results negatively. For instance, if one HFT firm is executing a buy strategy based on pattern recognition, while another firm may be executing a sell strategy based on the same data or predictive model. If the latter’s trading volume is larger or executed faster, it may lead to market price trends contrary to the expectations of the former, resulting in losses for the former.

- Unpredictable market participant behavior (): Market participant behavior may be driven by various factors, including irrational behavior, making it extremely difficult to predict the behavior of other participants. For example, the 2021 GameStop (GME) trading event[22] demonstrated the extreme unpredictability of collective market participant behavior when driven by non-traditional factors such as collective action on social media. This behavioral pattern is far from predictable based on traditional financial theories and is challenging for HFT algorithms to accurately forecast.

- Opponents using covert strategies (): New participants may continuously join the market, employing covert strategies or using technologies not widely known, adding additional uncertainty to market behavior. For example, an emerging HFT firm may develop an advanced artificial intelligence algorithm capable of identifying and exploiting minor fluctuations in the market more rapidly. The deployment of such a new algorithm may suddenly alter market dynamics, causing unexpected impacts on existing participants.

2.2. Uncertainty of Internal Conditions

2.2.1. System Uncertainty

- Network latency (): In HFT, even milliseconds of delay can lead to significant losses, as market conditions can change drastically within extremely short periods. For instance, suppose a trading firm relies on the fastest network connection from New York to London to execute arbitrage strategies. However, due to the cross-geographical nature, the risk associated with network connectivity is much higher compared to intra-geographical risks. If this network connection experiences delays due to technical issues, the firm may miss out on executing lucrative trades, or worse, may fail to withdraw in time before market conditions deteriorate, resulting in losses.

- Processing latency (): The impact of processing latency on HFT is significant, as in this trading mode, the advantages of every millisecond or even microsecond can determine profits or losses. For example, a company encounters technical issues during the development of its trading system, resulting in a 5-millisecond delay in the execution of trade orders. Although seemingly insignificant, in the world of HFT, such delays can have substantial effects. Due to execution latency, when the company’s algorithms identify an arbitrage opportunity and attempt to execute trades, market prices have already adjusted, causing the arbitrage opportunities to vanish. This implies that the company may have missed out on numerous potentially profitable trading opportunities.

- System failures (): Defects introduced during software updates or modifications are common issues in HFT systems. Even with rigorous testing, defects may remain undetected, especially those that manifest only in actual trading environments. For instance, a financial services company in 2012 updated its trading software one day, and a flaw in the new software resulted in abnormal behavior of the trading system, erroneously executing millions of orders at high speed that should not have been executed. Within less than an hour, this system failure incurred hundreds of millions of dollars in losses for the company. This event underscores the importance of software updates and defect management in HFT systems. When new code runs in an actual trading environment, even after rigorous testing, undiscovered software defects may exist.

2.2.2. Differences in Content Understanding

- Differences in market data interpretation (): Various HFT algorithms may interpret the same set of market data differently, leading to divergent or diversified trading decisions. For instance, during the release of significant information in the stock market, different HFT systems may have varied interpretations of the positive or negative impact of the data. Some algorithms may interpret it as a bullish signal and opt to buy related stocks, while others may perceive it as bearish and choose to sell. Such differences in content understanding can increase market volatility in a short period.

- Diverse interpretations of news reports (): News reports and announcements often contain ambiguous or multi-interpretable language, prompting different trading systems to interpret this information based on their algorithms. For example, if a large tech company’s financial report exceeds market expectations but its future revenue forecast appears slightly conservative, various HFT systems may react differently. Some may focus on the short-term bullish aspects and buy, while others may be concerned about the uncertainty in long-term revenue forecasts and choose to sell. Such diversity in news interpretation can lead to significant fluctuations in stock prices.

- Differing interpretations of regulatory announcements (): Regulatory announcements from governing bodies typically have a direct impact on the market, but the complexity of their language and terms sometimes leads to varying interpretations and expectations. For example, if a regulatory agency issues new rules aimed at tightening oversight of HFT, some trading entities may interpret it as a direct threat to their business model and decrease trading activities. In contrast, others may seek gray areas within the new regulations, attempting to adjust their strategies to continue leveraging the advantages of HFT. Such differing interpretations of regulatory content may result in divergent behaviors among market participants, consequently affecting market structure and liquidity.

2.3. Regulatory Uncertainty

2.3.1. Changes in Regulatory Interpretations

- Increased compliance costs (): Regulatory agencies’ new interpretations of existing rules may escalate compliance costs for enterprises. Companies may need to allocate additional resources to comprehend new interpretations, adjust their business processes, update compliance strategies, or even redesign products or services. For instance, financial regulatory bodies may reinterpret rules regarding algorithmic trading, necessitating entities employing algorithms in trading to engage in more frequent self-assessment and reporting. For HFT firms, this could entail investment in advanced compliance monitoring systems, thereby escalating operational costs.

- Adjustment of business models (): When regulatory interpretations change, businesses may need to modify their business models, especially if the new interpretations impact their core revenue streams. For example, if regulatory bodies decide to classify a widely adopted HFT strategy as market manipulation, trading firms relying on this strategy may have to completely revamp their trading models, potentially affecting their profitability and business continuity.

2.3.2. Regulatory Enforcement

- Increased transparency requirements (): Regulatory bodies demanding enhanced transparency in situations necessitating more disclosure of trading information may affect the operational methods of HFT firms. For instance, regulatory agencies may require all trading entities, including HFT firms, to provide more detailed trading data and strategy information to augment market transparency. This may compel HFT entities to adjust their data reporting processes and systems. While this aids regulatory bodies in better monitoring market activities, it may also increase the operational burden and costs for trading firms, as well as the risk of technology strategy leaks.

- Enhanced monitoring of abnormal trading activities (): Regulatory agencies intensifying monitoring efforts on abnormal trading activities, especially those indicative of market abuse or manipulation, represent a significant change. For example, regulatory bodies adopting more advanced surveillance technologies to identify abnormal trading patterns may more frequently flag certain trading activities of HFT firms as suspicious. This may result in these firms facing more investigations and reviews, compelling them to adjust trading algorithms to mitigate the risk of being flagged by regulatory agencies as suspicious trades.

3. Problem Definition

3.1. Incompleteness of Content

- Lack of descriptive details in the legislation: Initially, the legislation lacked specific details, including the identification and management of trading activities deemed to pose risks to market stability, compliance with targeted regulatory requirements, understanding regulatory expectations, and addressing potential regulatory enforcement and penalty standards.

3.2. Inconsistency of Content

- Lack of descriptive details in the legislation: Initially, the legislation lacked specific details, including the identification and management of trading activities deemed to pose risks to market stability, compliance with targeted regulatory requirements, understanding regulatory expectations, and addressing potential regulatory enforcement and penalty standards.

3.3. Imprecision of Content

- Ambiguity in regulatory requirements and boundaries: Due to certain provisions of the legislation being rather vague, HFT companies are required to expend more resources in interpreting regulations to ensure compliance with legal requirements. This entails not only direct financial costs, such as hiring legal consultants for advice, but also time costs, especially in the initial phase of new regulations. The uncertainty regarding compliance may necessitate a more cautious approach by companies, thereby slowing down their decision-making and trading speed.

3.4. Incorrectness of Content

- Misunderstanding of HFT definition: The lack of clear definition or ambiguity in the definition of HFT in the regulations may lead to misunderstandings among companies. This could result in the incorrect adjustment or cessation of certain legitimate trading strategies, or the oversight of some regulated activities.

| Data | Information | Knolwdge | Wisdom | Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | N/A | The uncertainty caused by inconsistency lies in the differences in interpreting trading data, such as varying understandings of what constitutes "abnormal trading behavior." | Inconsistencies in data quality and completeness may affect knowledge construction, such as developing risk assessment models based on incomplete trading data. | Subjectivity in data interpretation may influence wise judgments regarding compliance and risk, such as how to remain competitive while adhering to regulatory requirements. | The objectives of data collection may vary due to inconsistent understandings, such as collecting data related to regulatory reporting vs. data related to profit optimization. |

| Information | N/A | N/A | Different interpretative frameworks of information may lead to inconsistencies in knowledge construction, such as varying understandings of market trends. | In the transformation from information to wisdom, stakeholders’ values may result in different uses of the same information, influencing decisions regarding compliance and risk management. | Inconsistent interpretation of information and goal setting may result in a disconnect between objectives and actual operations, such as misunderstandings of regulatory information leading to non-compliant transactions. |

| Knowledge | N/A | N/A | N/A | The transformation of knowledge into wisdom is influenced by individual or corporate values, which may lead to different applications of compliance and ethical standards. | Inconsistencies between knowledge and purpose may result in strategy implementation not aligning with company objectives, such as conflicts between risk preferences and compliance requirements. |

| Wisdom | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Wisdom significantly influences the formation of purpose, but differences in individual or team values may lead to different strategies and goal setting. |

| Purpose | The direction of data collection and analysis is influenced, but if the goals are unclear or changeable, it may result in inconsistent data strategies. | Purpose-driven information needs, if inconsistent with actual operations, may lead to overlooking important information. | Purpose influence the direction of knowledge application, and inconsistency may result in a disconnect between strategic execution and actual needs. | Purpose are influenced by wisdom, but inconsistent values may lead to misjudgments in execution direction. | N/A |

| Data | Information | Knowledge | Wisdom | Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | N/A | Ambiguous regulatory requirements may result in collected data not meeting the expectations of regulatory agencies. | Insufficient data can impact the accurate understanding of regulatory implications. | Data uncertainty leads to incomplete considerations in decision-making. | The imprecision of data results in the inability to accurately devise compliance strategies. |

| Information | N/A | Imprecise interpretation of information leads to discrepancies in understanding regulations. | The diversity of information results in ethical decision-making dilemmas. | Imprecise information affects the clarity of compliance objectives. | N/A |

| Knowledge | Enhancing understanding of regulatory purpose. | N/A | Limited knowledge restricts effectiveness in complex decision-making. | Knowledge constraints impact strategy formulation and goal attainment. | Enhancing understanding of regulatory purpose. |

| Wisdom | Data selection and optimization from the perspective of wisdom. | Wisdom guides deeper information analysis. | Wisdom aids in identifying critical knowledge. | N/A | Wisdom directs goal setting and strategic realignment. |

| Purpose | Purpose-driven data collection and analysis. | Clear goal-setting guides information gathering and utilization. | Objective-driven accumulation and application of knowledge. | N/A | N/A |

| Data | Information | Knowledge | Wisdom | Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | N/A | Data of incompleteness or incorrectness collection. | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Information | N/A | N/A | Misinterpretation or oversimplification of information. | N/A | N/A |

| Knowledge | N/A | N/A | N/A | Decision-making based on incorrect information. | N/A |

| Wisdom | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Wisdom directs goal setting and strategic realignment. |

| Purpose | Collecting irrelevant or misleading data. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

4. Problem Processing

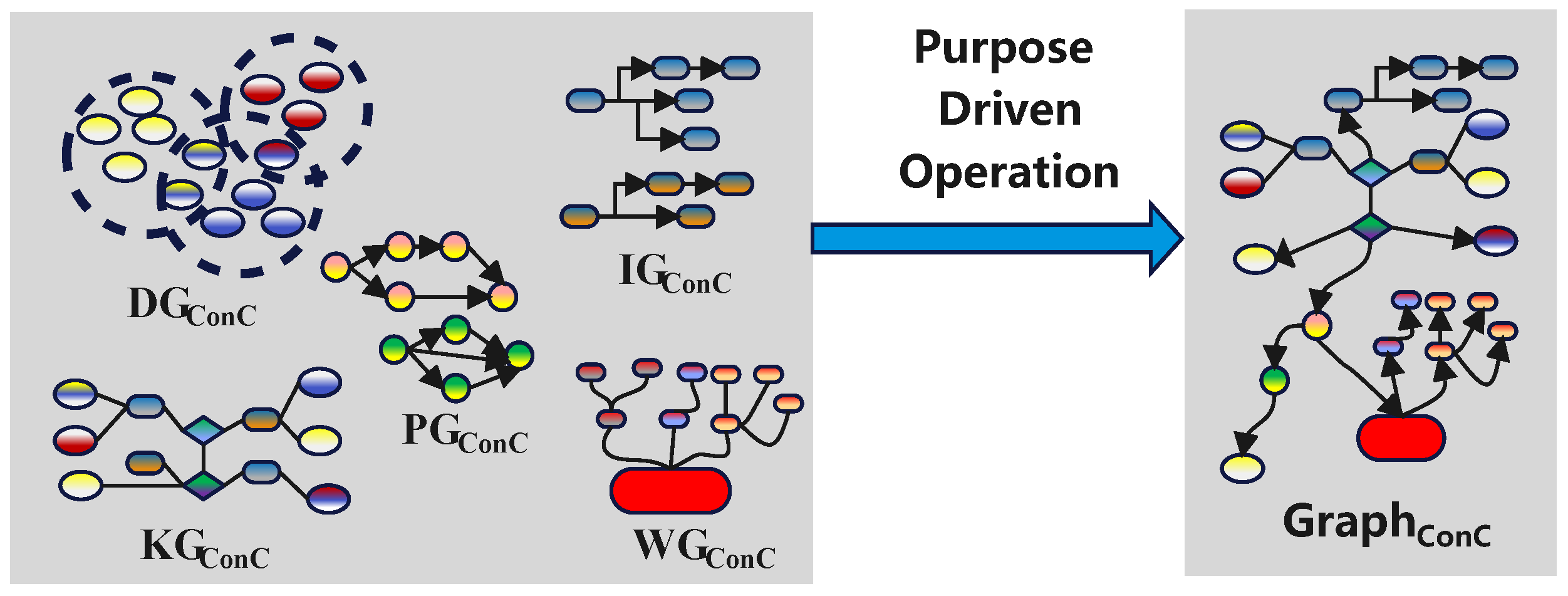

4.1. Concept Space

4.1.1. Definition

4.1.2. Basic Attributes

- According to the definition of HFT [26], where the attribute is:the attributes represented by from to respectively are: whether it is algorithmic trading, whether high-speed and sophisticated computer programs or systems are used for trading, order-to-trade ratio threshold, short-term holding threshold, and whether positions are closed at the end of the trading day.

- Regulatory boundaries , with attributes as follows:where attributes represented by through respectively are: statutory item, type of regulation, upper regulatory limit, lower regulatory limit, and penalty content.

- Interpretation details of the legislation , with attributes as follows:where represents the content of the statute, represents the provisions of the statute, and represents the interpretation of the statute.

4.1.3. Relation

-

The relationship between HFT definition and legislative interpretation details:In the preceding equation, the relational link signifies the association between the definition of HFT and the specific interpretation of its regulatory content, thereby ensuring completeness and consistency for stakeholders within the concept space.

-

The relationship between regulatory boundaries and legislative interpretation details:In the previous equation, the relational link signifies the association between each regulatory boundary and the specific interpretation of legislative content, ensuring stakeholders’ understanding of the precision and correctness of regulations within the concept space.

4.1.4. Operation

-

Query operation:The querying operation involves retrieving a relevant set of concepts within the concept space based on query conditions q (such as specific attributes or relations). It can be expressed as follows:We can utilize the aforementioned equation to query all concepts related to HFT, for instance, retrieving all companies employing HFT within a certain order-to-trade ratio range.

-

Add operation:We can add a new concept v to the concept set using the following equation:For example, due to the addition of a new regulation, we need to add the interpretation of this regulation to the corresponding concept set.

-

Modify operation:Furthermore, we can maintain the relevant attributes of existing concepts through the following operation:For example, due to changes in the thresholds for HFT stipulated in the regulations, we need to modify the threshold attribute in the HFT definition clause to update the concept space.

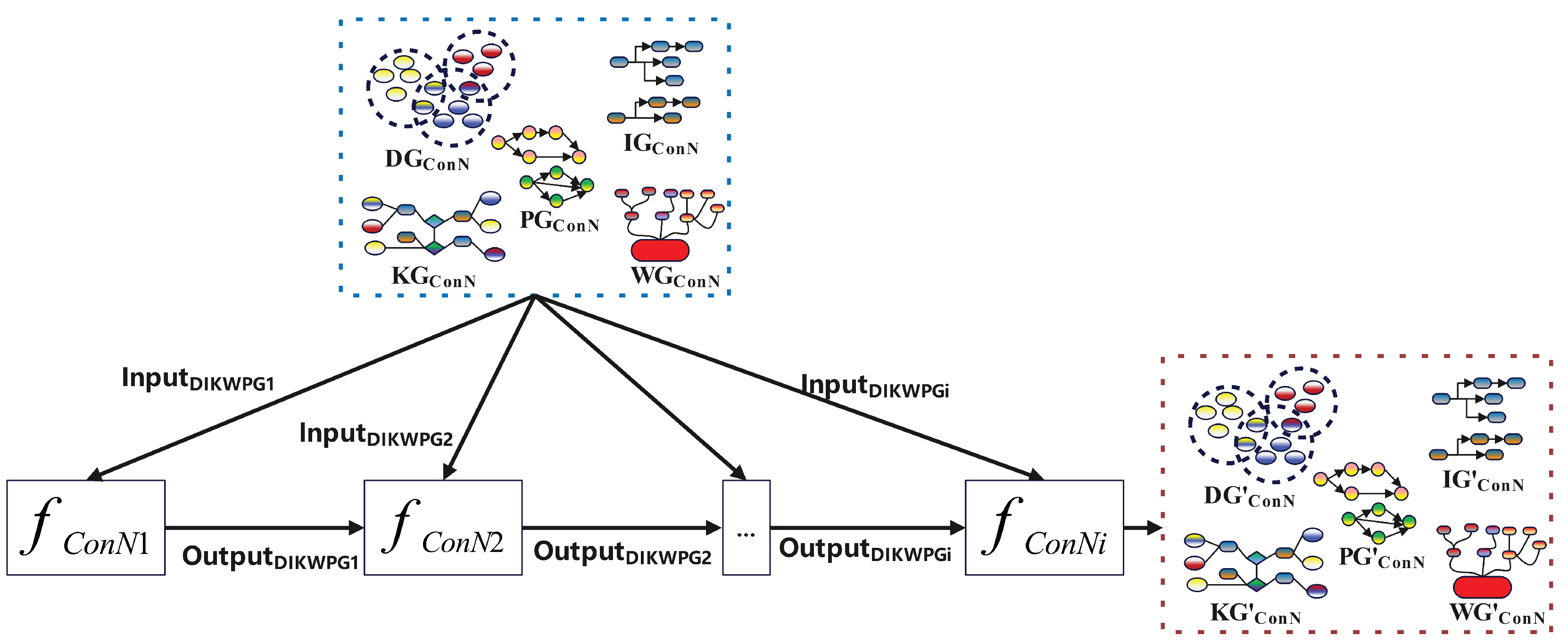

4.2. Cognitive Space

4.2.1. Definition

4.2.2. Input and Output Space

- Input space represents the collection of perceived data or information in Figure 3, which can originate from observations from the external world, signals received from other systems, or internally generated data.For the cognitive content input space of n financial companies, there is only one, denoted as , representing the input of legislative content.

- Output space represents the collection of processed understandings or decisions in Figure 3, which may include categorization of information, formation of concepts, determination of purpose, or establishment of action plans. For the cognitive content output space of n financial companies, there are n spaces, denoted as

4.2.3. Cognitive Processing

4.3. Semantic Space

4.3.1. Definition

4.3.2. Semantic Units and Relations

-

Query operation:The previous equation returns a set of semantic units that satisfy the query condition q.

- Add operation:, adds a new semantic unit v to the set .

- Update operation:, updates or adds the relationship e between semantic units v and .

4.3.3. Operation and Application

- We define a semantic unit to represent interpretation bias, which belongs to the legal semantic space:

- We can use query operations to retrieve units of inconsistency in the execution process:where condition q is interpretation bias in law.

- The addition operation can be utilized to enrich the semantic space of legal understanding:where represents semantic units reflecting accurate legal comprehension.

- Furthermore, the semantic space can also be refined through update operations, as illustrated by the following equation.where is comprehending bias and the purpose of this operation is to establish new semantic units, , representing the understanding biases existing alongside the accurate legal comprehension .

4.4. Crossing-Space Processing of DIKWP

4.4.1. Mapping from Concept Space to Cognitive Space

-

Definition: The concepts in the concept space are combined through the intrinsic cognitive mechanisms of individuals or systems, along with personal experience and knowledge, to form unique understandings and interpretations.Equation (21) represents the process from the concept to cognitive processing , reflecting how individuals understand and interpret concepts.

- Application: For instance, financial firms adjust parameters related to high-frequency trading based on their trading and system development experience, ensuring compliance with the concept attributes of the regulatory boundary . Hence, this process can be regarded as a mapping from the concept space to the cognitive space.

4.4.2. Mapping from Cognitive Space to Semantic Space

-

Definition: Transforming internal understanding within the cognitive space into semantic expressions that can be comprehended and accepted by the external world.Equation (22) represents the transformation from cognitive processing to semantic expression, encompassing the selection and organization of language and symbols to accurately articulate cognitive content.

- Application: For instance, in situations where regulatory boundaries are ambiguous, some provisions merely describe illegal boundaries descriptively rather than quantitatively. However, as current computer systems require qualitative analysis of inputs to ensure the accuracy of outputs, it is necessary not only to represent these fuzzy boundaries in the semantic space and input them but also to first convert the expression of fuzziness into concepts in the cognitive space before processing them into parameters of the trading system to ensure compliance with legal standards. In the aforementioned process, we can interpret and express the mapping and processing from cognitive space to semantic space using Equation (22).

4.4.3. Feedback from Semantic Space to Concept Space and Cognitive Space

-

Definition: Feedback from the external world to semantic expression is transmitted through the semantic space, thereby influencing concept space and cognitive space, forming a closed-loop process of cognitive updating and learning.Equations (23) and (24) respectively represent the feedback process from semantic expression to concept updating and cognitive updating, achieving dynamic adjustments and learning of internal understanding and concepts in response to external feedback.

- Application: For instance, when a financial company faces penalties, it generates new semantic content and expressions regarding the regulatory boundaries of the legislation. The penalties prompt the company to develop new conceptual attributes regarding the legislation and to perform corresponding operations on its previously vague concept space. As the concept space changes, the mapping function from concept space to cognitive space varies accordingly, resulting in new cognition that is reflected in concrete actions. This refers to the process of handling the "4-N" problems under the acceptance of external feedback and purpose-driven circumstances, as outlined in the definition: this process constitutes a closed-loop cognitive updating and learning process.

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Lange, A.C.; Lenglet, M.; Seyfert, R. Cultures of high-frequency trading: Mapping the landscape of algorithmic developments in contemporary financial markets. Economy and Society 2016, 45, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogaard, J.; Hendershott, T.; Riordan, R. High-frequency trading and price discovery. The Review of Financial Studies 2014, 27, 2267–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkveld, A.J. The economics of high-frequency trading: Taking stock. Annual Review of Financial Economics 2016, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’hara, M. High frequency market microstructure. Journal of financial economics 2015, 116, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baily, M.N.; Klein, A.; Schardin, J. The impact of the Dodd-Frank Act on financial stability and economic growth. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 2017, 3, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, X.; Wu, J. Data privacy protection for edge computing of smart city in a DIKW architecture. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2019, 81, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Sun, X.; Che, H.; Cao, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, X. Modeling data, information and knowledge for security protection of hybrid IoT and edge resources. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 99161–99176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Duan, Y.; Yu, L.; Che, H. Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 250–267. ISBN 978-3-031-24386-8. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, R.F. Ambiguity Aversion in Algorithmic and High Frequency Trading. SSRN.

- Dai, L.; Zhang, B. Political uncertainty and finance: a survey. Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies 2019, 48, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matousek, R.; Panopoulou, E.; Papachristopoulou, A. Policy uncertainty and the capital shortfall of global financial firms. Journal of Corporate Finance 2020, 62, 101558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.C.; Zheng, D. An empirical analysis of herd behavior in global stock markets. Journal of Banking & Finance 2010, 34, 1911–1921. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.W.; Cliff, M.T. Investor sentiment and the near-term stock market. Journal of empirical finance 2004, 11, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benesh, G.A.; Peterson, P.P. On the Relation Between Earnings, Changes, Analysts’ Forecasts and Stock Price Fluctuations. Financial Analysts Journal 1986, 42, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomp, J. Financial fragility and natural disasters: An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial stability 2014, 13, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidis, L.; Daskalakis, G.; Markellos, R.N. Does the weather affect stock market volatility? Finance Research Letters, 7, 214–223.

- BALDAUF, M.; MOLLNER, J. High-Frequency Trading and Market Performance. The Journal of Finance 2020, 75, 1495–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulmerich, M.; Leporcher, Y.M.; Eu, C.H. Stock Market Anomalies. In Applied Asset and Risk Management: A Guide to Modern Portfolio Management and Behavior-Driven Markets; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 175–244. ISBN 978-3-031-24386-8. [Google Scholar]

- Serbera, J.P.; Paumard, P. The fall of high-frequency trading: A survey of competition and profits. 36, 271–287.

- Goldstein, M.A.; Kwan, A.; Philip, R. High-frequency trading strategies. Available at SSRN 2973019, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brogaard, J.; Garriott, C. High-Frequency Trading Competition. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 2019, 54, 1469–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malz, A.M. The GameStop episode: what happened and what does it mean? Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 2021, 33, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, M.; Brogaard, J.; Hagströmer, B.; Kirilenko, A. Risk and return in high-frequency trading. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 2019, 54, 993–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Zhu, W. Short-sales and stock price crash risk: Evidence from an emerging market. Economics letters 2016, 144, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jank, S.; Roling, C.; Smajlbegovic, E. Flying under the radar: The effects of short-sale disclosure rules on investor behavior and stock prices. Journal of Financial Economics 2021, 139, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharudin, K.Z.; Young, M.R.; Hsu, W.H. High-frequency trading: Definition, implications, and controversies. Journal of Economic Surveys 2022, 36, 75–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Information | Knowledge | Wisdom | Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | N/A | Ambiguous Legislation: Vague definitions hinder accurate translation into regulatory information. | Unclear Provisions: Lack of explicit guidelines hampers the conversion of data into knowledge. | Diverse Data Interpretation: Varied interpretations may lead to different decision-making strategies. | Unclear Business Objectives: Data fails to directly reflect the company’s specific purpose. |

| Information | Over-Simplification: Simplifying complex information into data may lead to the loss of critical details | N/A | Information Overload: A vast amount of regulatory information may be challenging to integrate into practical knowledge. | Subjectivity in Interpretation: Subjective interpretations of information may influence decision-making. | Disconnect between Information and Objectives: Collected information may not accurately reflect the pathway to achieving purpose. |

| Knowledge | Underutilization: Existing knowledge fails to translate into practically actionable data. | Lag in Updates: Delayed knowledge updates result in inaccurate information interpretation. | N/A | Knowledge Limitations: Inherent knowledge may restrict innovative decision-making. | Execution Bias: Existing knowledge may not fully align with the requirements for implementing new regulations. |

| Wisdom | Practice Deficiency: Wisdom is challenging to directly translate into specific data operations. | Ethical Considerations: Ethical and moral considerations influence information processing. | Innovation Constraints: Traditional wisdom may limit the acceptance of new knowledge. | N/A | Decision Conflicts: Considerations based on wisdom may conflict with business purpose. |

| Purpose | Difficulty in Concretizing Objectives: purpose is challenging to be transformed into clear data forms. | Goal-oriented Information Selection: Selecting information based on purpose may overlook crucial data. | Strategy Formulation: Purpose guide the formation and application of knowledge strategies. | Value-Driven Decision Making: Purpose influence the application of wisdom and decision-making direction. | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).