Submitted:

02 April 2024

Posted:

03 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. HIV Epidemiology

1.2. Scoping Review

2. Materials and Methods

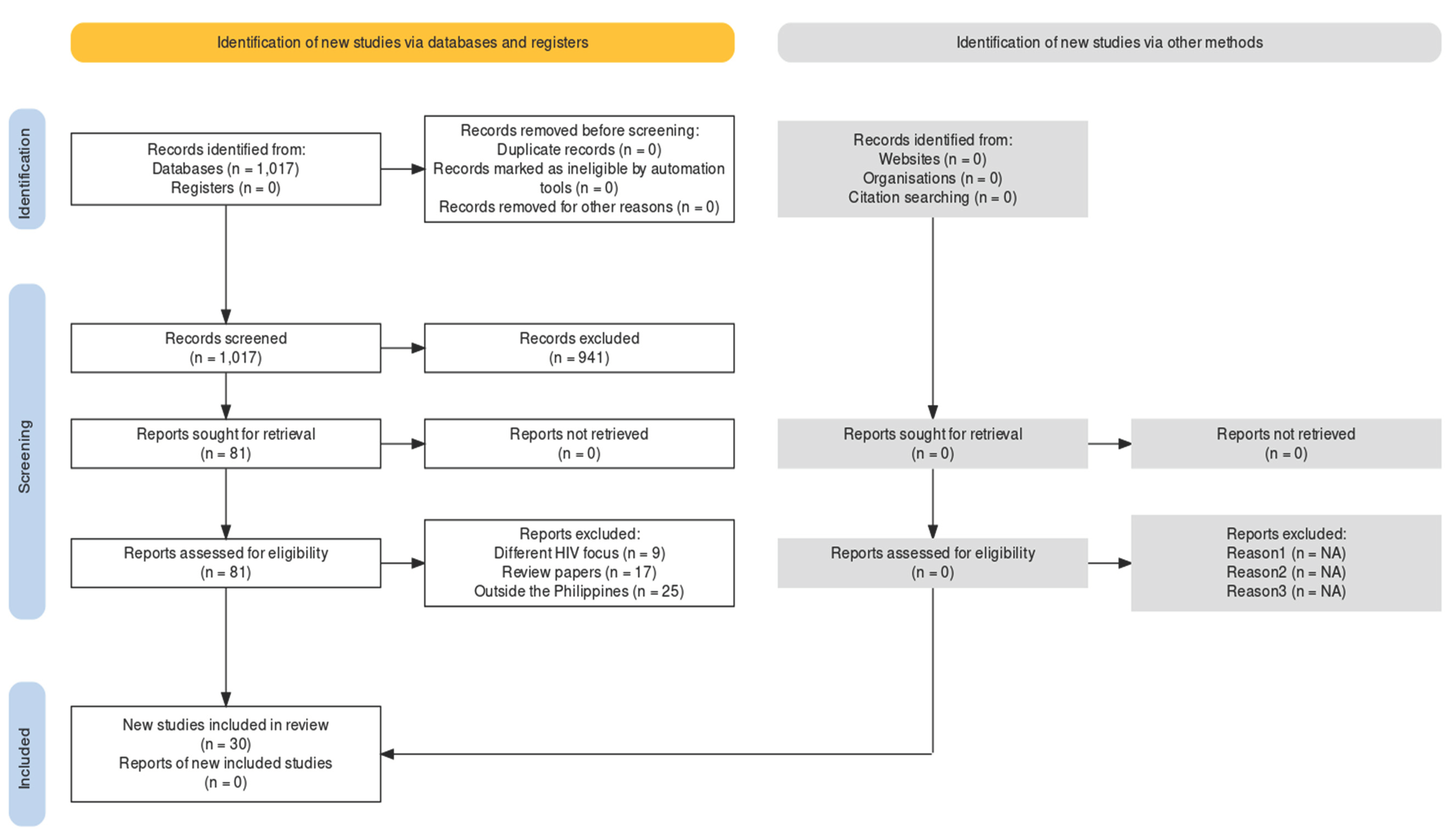

2.1. Study Search Procedures

2.2. Search Outcome and Quality Appraisal

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.4. Coding Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Reporting Review Findings

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Evidence

3.2. Factors Contributing to the High HIV Incidence in the Philippines

3.2.1. Individual Factors

3.2.2. Sociocultural Factors

3.2.3. Economic Factors

3.2.4. Environmental Factors

3.2.5. Political Factors

3.2.6. Educational Factors

3.2.7. Biological Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Included Evidence

4.2. Factors Contributing to the High HIV Incidence in the Philippines

5. Conclusion

5.1. Conclusion

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). HIV Country Profiles, 2022. Cfs.hivci.org. https://cfs.hivci.org/.

- Gangcuangco, L. M. A., & Eustaquio, P. C. The state of the HIV epidemic in the Philippines: progress and challenges in 2023. Trop Med and Inf Dis, 2023, 8(5), 258. [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Philippines. 2016. Unaids.org. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/philippines.

- Devi, S. Stigma, politics, and an epidemic: HIV in the Philippines. The Lancet, 2019, 394, 2139-2140. [CrossRef]

- Govender, R.D., Hashim, M.J., Khan, M., Mustafa, H., & Khan, G. Global epidemiology of HIV/AIDS: a resurgence in North America and Europe. J of Epidemiology and Global Health, 2021, 11(3), 296-301. [CrossRef]

- Department of Health (DOH). HIV/AIDS & ART Registry of the Philippines – April 2022. 2022. Manila, Philippines. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BA1SvIP3wkLrpSq1BjV57jjTzh7rQJxC/view?usp=sharing.

- De Torres, R.Q. Facilitators and barriers to condom use among Filipinos: A systematic review of literature. Health Promot Perspect. 2020 Nov 7;10(4):306-315. PMID: 33312926; PMCID: PMC7722996. [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, K.R., d’Aquila, E., Fonner, V., Kennedy, C., & Sweat, M. Can policy interventions affect HIV-related behaviors? A systematic review of the evidence from low- and middle-income countries. AIDS Behavior, 2017, 21, 626-642. [CrossRef]

- Pitpitan, E.V. & Kalichman, S.C. Reducing HIV risks in the places where people drink: prevention interventions in alcohol venues. AIDS Behavior, 2016, 20:S119. [CrossRef]

- Restar, A., Nguyen, M., Nguyen, K., Adia, A., Nazareno, J., Yoshioka, E., et al. Trends and emerging directions in HIV risk and prevention research in the Philippines: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE, 2018, 13(12): e0207663. [CrossRef]

- Mak, S., & Thomas, A. An Introduction to Scoping Reviews. J of Graduate Med Educ, 2022, 14(5), 561–564. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D., Peters, M. D. J., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Alexander, L., Tricco, A. C., Evans, C., de Moraes, É. B., Godfrey, C. M., Pieper, D., Saran, A., Stern, C., & Munn, Z. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 2022, Publish Ahead of Print(3). [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18, e1230. [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.W. Publish or Perish. 2007. https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). 2018. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- SahBandar, I. N., May, G., Freda, E., Nalyn Siripong, Mahdi Belcaid, Schanzenbach, D., Leano, S., Haorile Chagan-Yasutan, Hattori, T., Shikuma, C., & Ndhlovu, L. C. Ultra-Deep Sequencing Analysis on HIV Drug-Resistance-Associated Mutations Among HIV-Infected Individuals: First Report from the Philippines. AIDS Res and Human Retroviruses, 2017, 33(11), 1099–1106. [CrossRef]

- Salvaña, E. M. T., Schwem, B. E., Ching, P. R., Frost, S. D. W., Ganchua, S. K. C., & Itable, J. R. The changing molecular epidemiology of HIV in the Philippines. Int J of Inf Dis, 2017, 61, 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Calaguas, N. P. Predictors of condom use among gay and bisexual men in the Philippines. Int J of Sexual Health, 2020, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ofreneo, M. A. P., Gamalinda, T. B., & Canoy, N. A. Culture-embedded drivers and barriers to (non) condom use among Filipino MSM: a critical realist inquiry. AIDS Care, 2020, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Adams, J., Coquilla, R., Montayre, J., Manalastas, E. J., & Neville, S. Views about HIV and sexual health among gay and bisexual Filipino men living in New Zealand. Int J of Health Promotion and Educ, 2020, 59(6), 342–353. [CrossRef]

- De Irala, J. Safe sex belief and sexual risk behaviors among adolescents. PubMed, 2016, 31(2), 185–190. [CrossRef]

- Deuba, K., Kohlbrenner, V., Koirala, S., & Ekström, A. M. Condom use behaviour among people living with HIV: a seven-country community-based participatory research in the Asia-Pacific region. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2017, sextrans-2017-053263. [CrossRef]

- Estacio, L., Estacio, J. Z., & Alibudbud, R. Relationship of psychosocial factors, HIV, and sex work among Filipino drug users. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gohil, J., Baja, E. S., Sy, T. R., Guevara, E. G., Hemingway, C., Medina, P. M. B., Coppens, L., Dalmacion, G. V., & Taegtmeyer, M. Is the Philippines ready for HIV self-testing? BMC Public Health, 2020, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Hall, B. J., Yang, X., Huang, L., Yi, G. Y., Chan, E. D., Tucker, J. D., & Latkin, C. A. Barriers and facilitators of rapid HIV and syphilis testing uptake among Filipino transnational migrants in China. Aids and Behavior, 2020, 24(2), 418–427. [CrossRef]

- Millalos, M. G., & Cutamora, J. From testing to coping: the voices of people living living with HIV/AIDS. Philippine J of Nursing, 2019, 89(2).

- Mosende, A. G., Lacambra, C. B., & De los Santos, J. A. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors toward HIV/AIDS among health care workers in urban cities in Leyte Philippines. Malaysian J of Nursing, 2023, 14(03), 185–193. [CrossRef]

- Palma, D. M., & Parr, J. Behind prison walls: HIV vulnerability of female Filipino prisoners. Int J of Prisoner Health. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pepito, V. C. F., & Newton, S. Correction: Determinants of HIV testing among Filipino women: Results from the 2013 Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey. PLOS ONE, 2021, 16(1), e0246013. [CrossRef]

- Bijker, R., Jiamsakul, A., Kityo, C., Kiertiburanakul, S., Siwale, M., Phanuphak, P., Akanmu, S., Chaiwarith, R., Wit, F. W., Sim, B. L., Boender, T. S., Ditangco, R., Rinke De Wit, T. F., Sohn, A. H., & Hamers, R. L. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia: a comparative analysis of two regional cohorts. J of the Int AIDS Society, 2017, 20(1), 21218. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-H. E., Gipson, J. D., Perez, T. L., & Cochran, S. D. Same-Sex Behavior and Health Indicators of Sexually Experienced Filipino Young Adults. Archives of Sex Beh, 2016, 45(6), 1471–1482. [CrossRef]

- Noble, M. D., & Austin, K. F. Gendered dimensions of the HIV pandemic: A cross-national investigation of women’s international nongovernmental organizations, contraceptive use, and HIV prevalence in less-developed nations. Sociological Forum, 2014, 29(1), 215–239. [CrossRef]

- Restar, A. J., Chan, R. C. H., Adia, A., Quilantang, M. I., Nazareno, J., Hernandez, L., Cu-Uvin, S., & Operario, D. Prioritizing HIV Services for Transgender Women and Men Who Have Sex With Men in Manila, Philippines. J of the Asso of Nurses in AIDS Care, 2019, 31(4), 1. [CrossRef]

- De los Santos, J. A., Tuppal, C., & Milla, N. The correlates of health facility-related stigma and health-seeking behaviors of people living with HIV. Acta Medica Philippina. 2022, . [CrossRef]

- Jegonia, F. (2019). “Stigma and level of care among health care providers to HIV/AIDS patients.” 2019. [CrossRef]

- Adia, A. C., Bermudez, A. N. C., Callahan, M. W., Hernandez, L. I., Imperial, R. H., & Operario, D. “An Evil Lurking Behind You”: Drivers, experiences, and consequences of HIV–related stigma among men who have sex with men with HIV in Manila, Philippines. AIDS Educ and Prev, 2018, 30(4), 322–334. [CrossRef]

- Melgar, J. L. D., Melgar, A. R., Festin, M. P. R., Hoopes, A. J., & Chandra-Mouli, V. Assessment of country policies affecting reproductive health for adolescents in the Philippines. Reproductive Health, 2018, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Restar, A. J., Adia, A., Nazareno, J., Hernandez, L., Sandfort, T., Lurie, M., Cu-Uvin, S., & Operario, D. Barriers and facilitators to uptake of condoms among Filipinx transgender women and cisgender men who have sex with men: A situated socio-ecological perspective. Global Public Health, 2019, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Hollingshead, B. M., Dowsett, G. W., & Bourne, A. “It’s like getting an Uber for sex”: social networking apps as spaces of risk and opportunity in the Philippines among men who have sex with men. Health Sociology Review, 2020, 29(3), 264–278. [CrossRef]

- Wong, J., Co, S. A., Espinosa, C. I., Zeck, W., Bermejo, R., & Silfverberg, D. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome benefit package: A financial review. Int J of Tech Assessment in Health Care, 2018, 34(S1), 54–55. [CrossRef]

- Ofreneo, M. A., & Canoy, N. Falling into poverty: the intersectionality of meanings of HIV among overseas Filipino workers and their families. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 2017, 19(10), 1122–1135. [CrossRef]

- Seposo, X. T., Okubo, I., & Kondo, M. Assessing frontline HIV service provider efficiency using data envelopment analysis: a case study of Philippine social hygiene clinics (SHCs). BMC Health Services Research, 2019, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Newman, P. A., Prabhu, S. M., Akkakanjanasupar, P., & Tepjan, S. HIV and mental health among young people in low-resource contexts in Southeast Asia: A qualitative investigation. Global Public Health, 2021, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Icamina, P. Internet “major” factor in Philippines’ HIV epidemic. Asia & Pacific. 2018, October 18. https://www.scidev.net/asia-pacific/news/internet-major-factor-in-philippines-hiv-epidemic/.

- Canoy, N. A., & Ofreneo, M. A. P. Struggling to care: A discursive-material analysis of negotiating agency among HIV-positive MSM. Health: An Interdisciplinary J for the Soc Study of Health, Illness and Med, 2016, 21(6), 575–594. [CrossRef]

- De Torres, R.Q., Pacquiao, D., Ngaya-an, F., & Tuazon, J. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and scheduled clinic visits of persons living with HIV in the Philippines. J of Nurs Practice and Rev of Research, 2021, 11(2), 19-30. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N=30 | Percentage(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Year of Publication 2014-2019 2020-2024 |

14 16 |

46.7 53.3 |

| Research Design Quantitative studies Qualitative studies |

17 13 |

56.7 43.3 |

| Population Men who have sex with men/gay men (with and without HIV) People living with HIV Women Community-based workers Healthcare professionals Key informants on HIV programs and policies Overseas Filipino workers Transgender women Prisoners |

12 9 3 3 3 3 2 2 1 |

40.0 30.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 6.70 6.70 3.33 |

| Factors | N=30 | Percentage(%) |

|---|---|---|

| HIV Contributory factors Individual factors Sociocultural factors Economic factors Environmental factors Political factors Educational factors Biological factors |

21 19 13 11 7 4 2 |

70.0 63.3 43.3 36.7 23.3 13.3 6.67 |

| No. | Author | Year | Methods | Relevant findings | Factors contributing to high HIV incidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adams et al. | 2021 | Qualitative descriptive n=19 Gay and straight men |

Lack of awareness on prevention other than condoms, unprotected sex; low HIV testing (requirement of immigration process); lack of education, accessibility of healthcare resources, lack of quality information on HIV; shame and stigma; lack of regular check-ups | Individual, sociocultural, political, educational, environmental |

| 2 | Adia et al. | 2018 | Qualitative; n=21 HIV+ MSM, community-based HIV workers |

Stigma influences testing and leads to late diagnosis and causes barriers to access to healthcare; religious society | Sociocultural |

| 3 | Bijker et al. | 2017 | Quantitative; n=3,994 PLHIV in Asia (including the Philippines) and Africa |

Sub-optimal adherence (SOA) is 4.8% in Asia; SOA to treatment is higher in MSM and IVDU; LMICs have higher SOA | Individual, economic, environmental |

| 4 | Canoy & Ofreneo | 2017 | Qualitative n=20 HIV+ gay men |

Fear of disclosure to family, friends, and co-workers due to stigma; entering into same sex relationship for financial support; Catholic culture | Individual, sociocultural, economic |

| 5 | Calaguas | 2020 | Quantitative n=491 MSM, gay men |

MSM, marital status, gender expression, relationship status, their predominant sexual position, and the sexes of their sexual partners are significantly associated with the use or non-use of condoms during their last sexual intercourse. | Individual |

| 6 | Cheng et al. | 2016 | Quantitative n=1,912 Young adults |

Same sex behavior is a predictor of age at first sex, lifetime substance abuse particularly smoking, and drug use. | Individual, sociocultural |

| 7 | Deuba et al. | 2018 | Quantitative n=3,827 in 7 Asia-Pacific countries including the Philippines |

55% has partners who are HIV+, 35% and 10% unknown; 43% practiced inconsistent condom use with regular partner and 46% with a casual partner; Filipinos have the highest sexual risk behavior with 63% inconsistent condom use with regular partner and 60% with a casual partner; lack of condom availability; lack of awareness that condom is still needed if both partners are HIV+. Living in rural areas less likely to report inconsistent condom use. More likely to report inconsistent condom use: sex workers, partners who are HIV+, those who do not know their partner’s status. | Individual, sociocultural, environment, economic |

| 8 | De Irala | 2016 | Quantitative; n=8,994 4 countries including the Philippines |

Low knowledge on condom effectiveness in preventing HIV; peer pressure not to use condom, wanted to feel having sex without condom | Individual, sociocultural |

| 9 | De los Santos et al. | 2022 | Quantitative n=100 |

Health workers who lack awareness of HIV care are prone to discriminating against people with HIV. Health care workers gossip about gay people with HIV. The experience of stigma is more prevalent in RHUs than hospitals, polyclinics and private treatment hubs. | Sociocultural, environment |

| 10 | De Torres et al. | 2021 | Quantitative PLHIV |

9% were non-adherent to treatment; time and activity constraints were the primary reasons for lack of adherence to ART and scheduled clinic visits. | Individual |

| 11 | Estacio et al. | 2021 | Quantitative, cross-sectional; n=292 Sex workers |

Sex work engagement high among drug users, abused individuals, and problems with friends; low HIV testing and case finding | Individual, sociocultural |

| 12 | Gohil et al. | 2020 | Qualitative; n=57 Key informants on HIV policies and HIV test users, MSM, TGW |

Policy and regulatory issues (no policy on HIV self-testing), conservative culture; poor HIV knowledge, cost, fake test kits | Individual, political, sociocultural, economic |

| 13 | Hall et al. | 2020 | Quantitative; n=1,362 OFW in Hong Kong |

Reasons for not having HIV testing: No perceived need, unwillingness, and no time (work) | Individual, economic |

| 14 | Hollingshead et al. | 2020 | Qualitative virtual ethnography MSM, community, key informants |

Use of gay dating mobile apps makes sex partners more accessible | Individual, sociocultural |

| 15 | Jegonia | 2019 | Quantitative Nurses and physicians Sample not specified |

Marked stigma among healthcare workers correlates with care and services provided. Religion, profession, workplace, and years of experience were significantly correlated with stigma. Stigma is inversely related with level of care. | Individual, sociocultural, economic, environment |

| 16 | Melgar et al. | 2018 | Qualitative Records analysis |

Restrictive policies, conservative religious society | Political, sociocultural |

| 17 | Milallos & Cutamora | 2019 | Qualitative, Husserlian phenomenology, n=7 PLHIV | High-risk sex practices | Individual |

| 18 | Mosende et al. | 2023 | Quantitative n=171 health care workers |

Lack of knowledge on HIV transmission | Individual |

| 19 | Newman et al. | 2022 | Qualitative n=132 Youth and key informants |

Peer, family (fear of disclosure), school (lack of discussion on sexual issues; fragmentation between educational and healthcare systems), and healthcare factors (lack of gender-affirmative health services); stigma and negative beliefs about HIV | Sociocultural, political, educational |

| 20 | Noble & Austin | 2014 | Quantitative n=women in 80 less-developed countries |

Democracy encourages women’s participation in HIV programs, female empowerment measured by schooling, having birth attendant at delivery, and fertility rates influence contraceptives rates and HIV rates; GDP influences women empowerment; Muslim influences HIV prevalence | Sociocultural, economic, political |

| 21 | Ofreneo & Canoy | 2017 | Qualitative n=13 OFW |

Risk of infecting spouse upon return from overseas work | Individual, sociocultural, economic |

| 22 | Ofreneo et al. | 2021 | Qualitative n=105 MSM |

Low socioeconomic status bisexual, multiple sex partners are unsafe | Individual, sociocultural, economic |

| 23 | Palma & Parr | 2021 | Qualitative n=18 Female prisoners |

Prison management and practices increases HIV risk, low HIV knowledge, increased vulnerability before prison | Individual, environment |

| 24 | Pepito & Newton | 2020 | Quantitative, secondary data analysis n=16,155 Women |

Low HIV testing (2.4%); tobacco use, middle class, TV/internet access, rural area, Muslim were more likely to get tested | Individual, sociocultural, environment |

| 25 | Restar et al. | 2019 | Qualitative phenomenology n=15 Health care providers (HCP) |

Hesitancy in providing HIV services due lack of awareness and training on health needs of MSM and TGW, and unsure how to prioritize HIV services. | Environment, education |

| 26 | Restar et al. | 2020 | Qualitative n=30 MSM, TGW |

Friends, lack of education in schools, church, cost, accessibility | Sociocultural, education, economic, environmental |

| 27 | SahBandar et al. | 2017 | Quantitative n=110 PLHIV |

Low ART treatment rate (0.9%); high HIV prevalence in IVDU; drug-resistant HIV variants; limited resources | Individual, sociocultural, environment, biological, political |

| 28 | Salvana et al. | 2017 | Quantitative n=81 |

Shift in HIV molecular biology with more resistant HIV strain and increased local transmission, low consistent condom use, transactional sex, sex with HIV+ individuals | Biological, individual, sociocultural, economic |

| 29 | Seposo et al. | 2019 | Quantitative; n=9 Social hygiene clinics (SHC) |

Higher HIV prevalence in areas with suboptimal SHCs | Environmental, economic, political |

| 30 | Wong et al. | 2020 | Quantitative | High cost and inconsistent implementation of AIDS treatment package | Economic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).