Submitted:

05 April 2024

Posted:

08 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire Validation

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

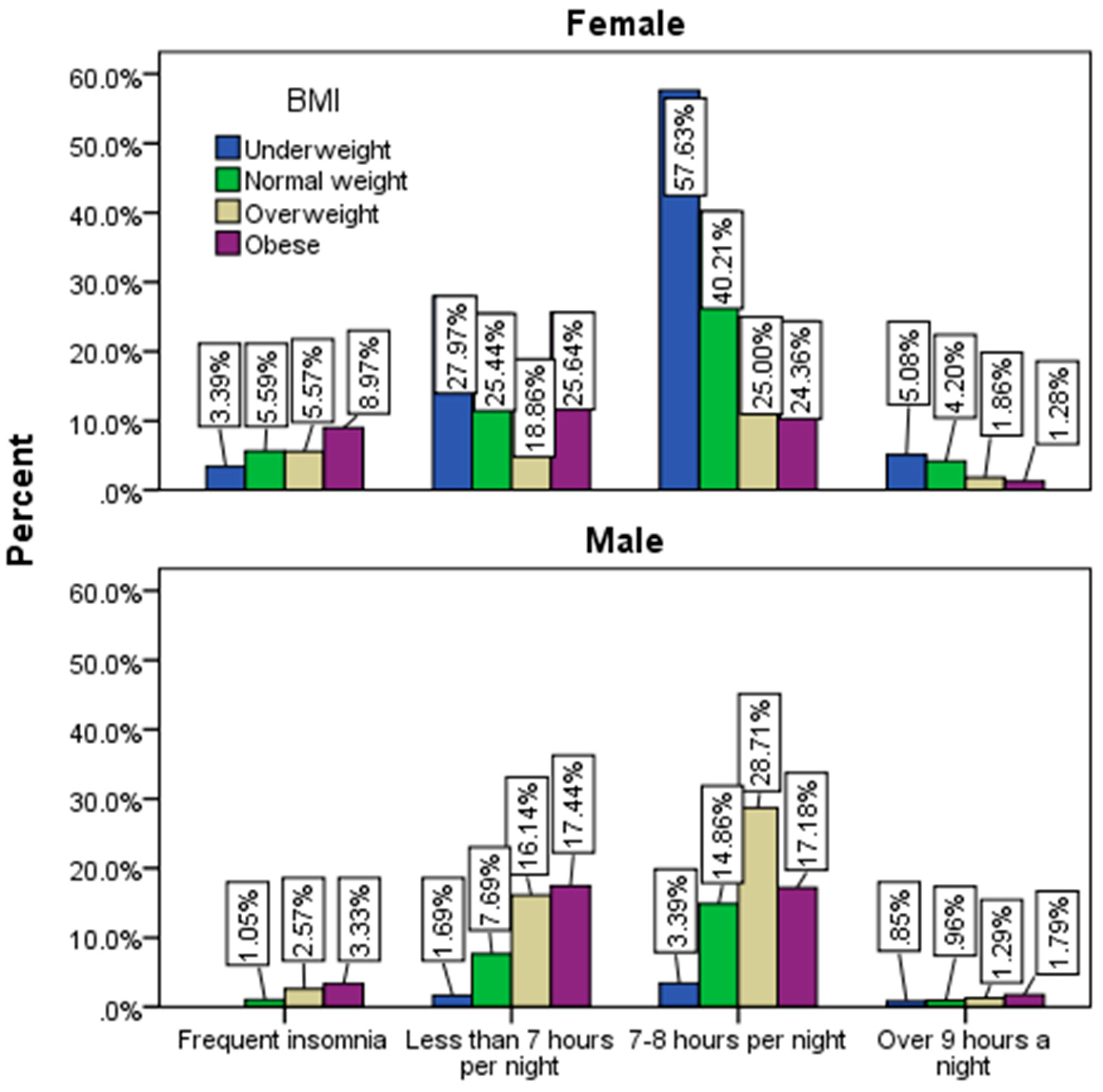

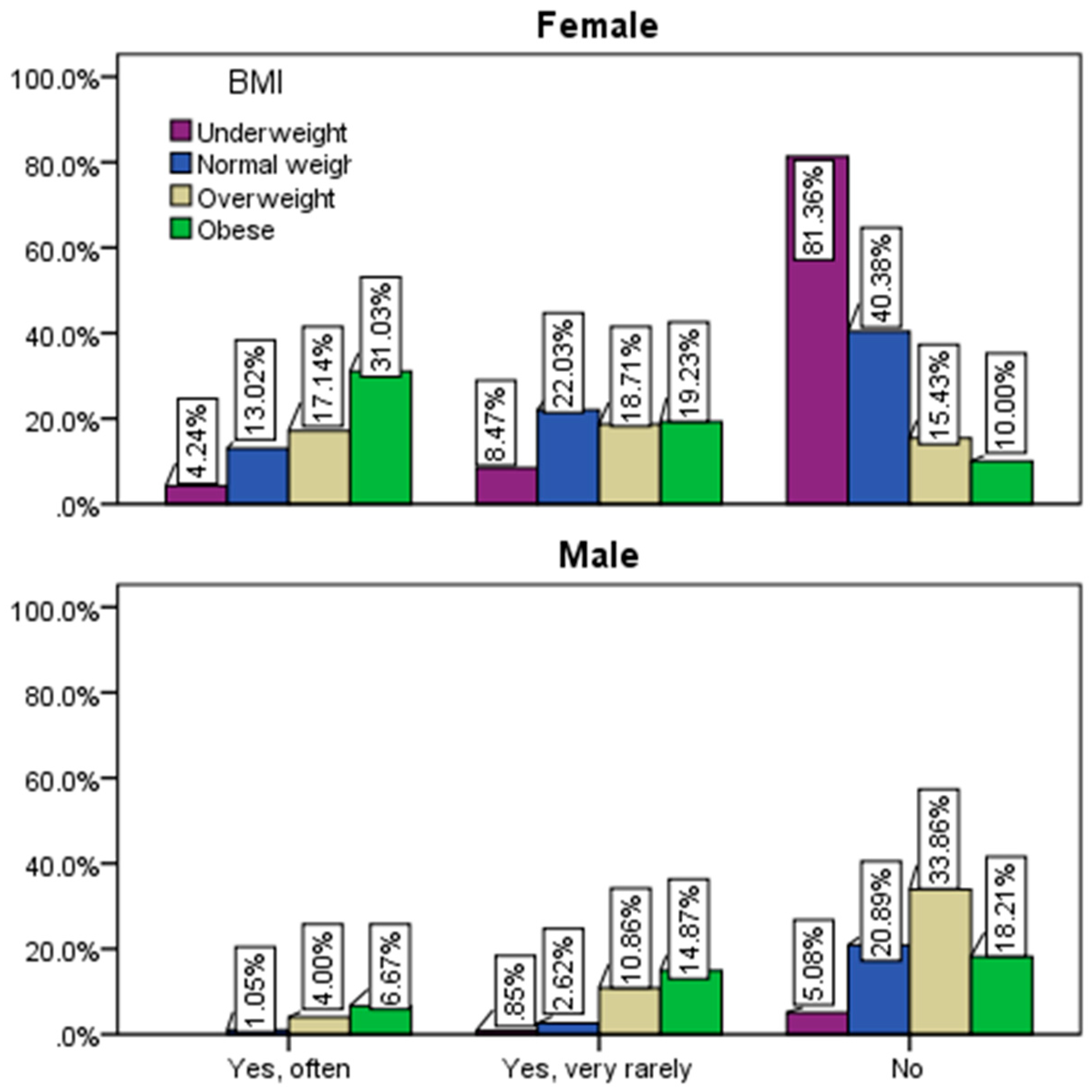

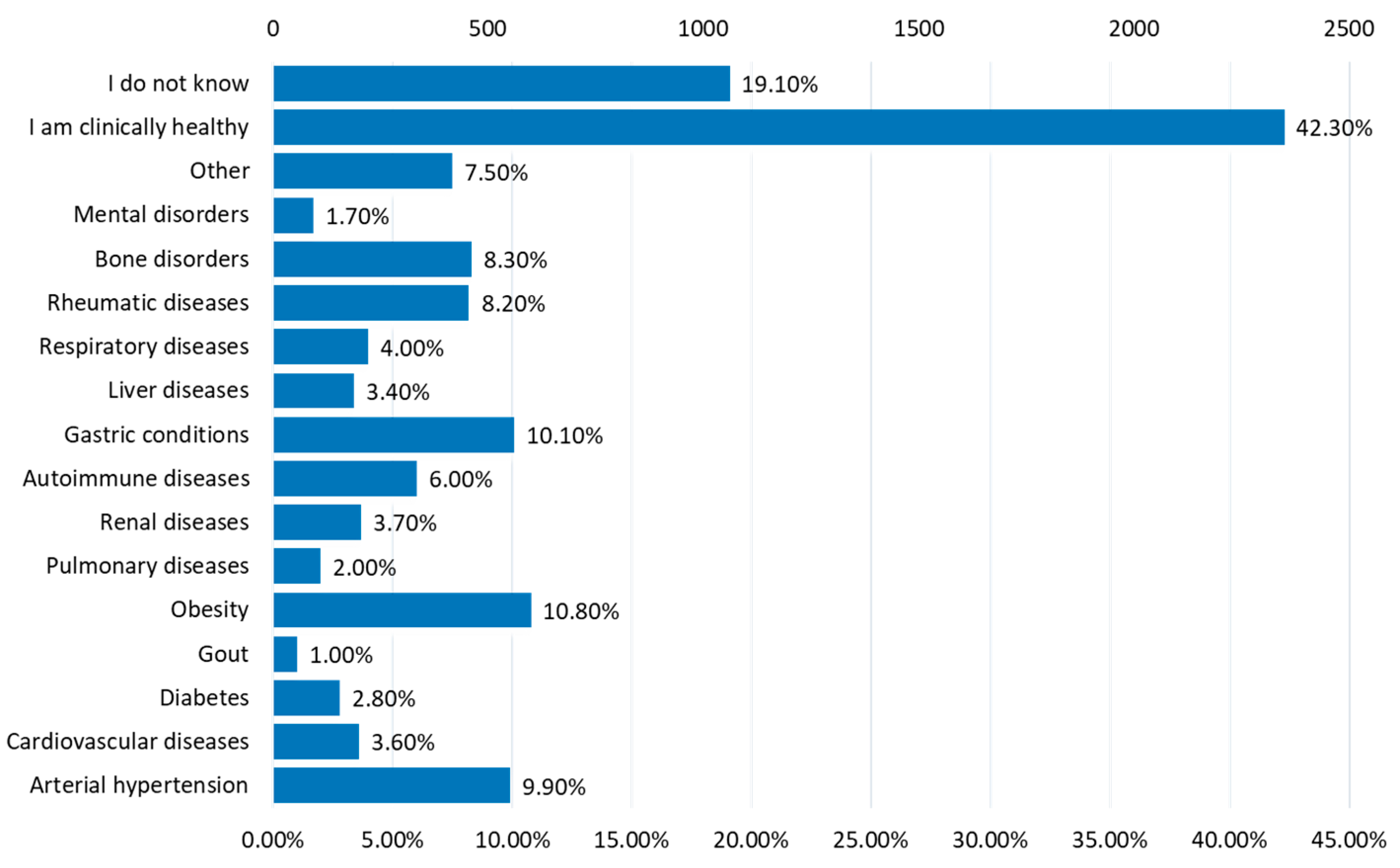

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Anthropometric Data

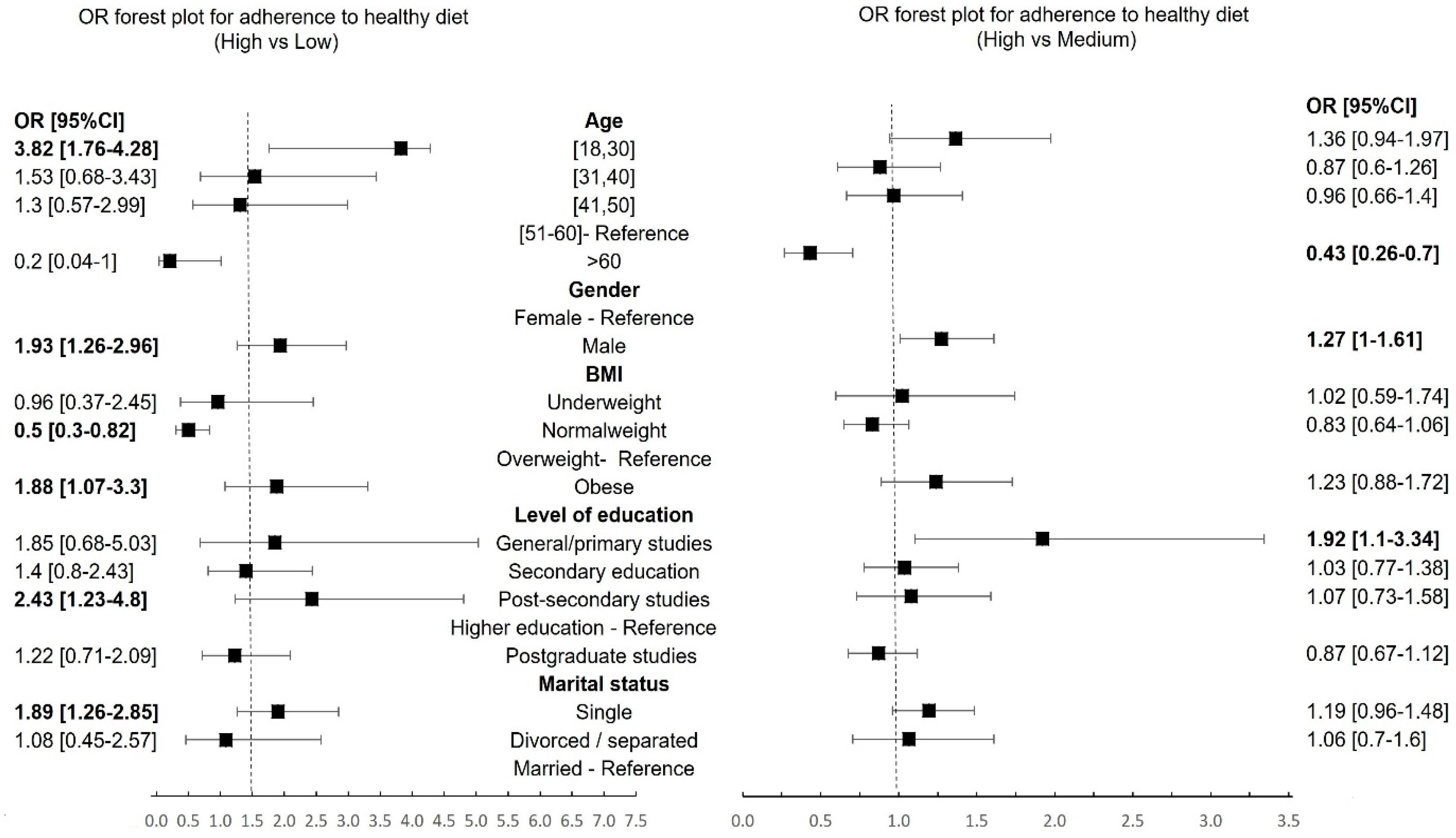

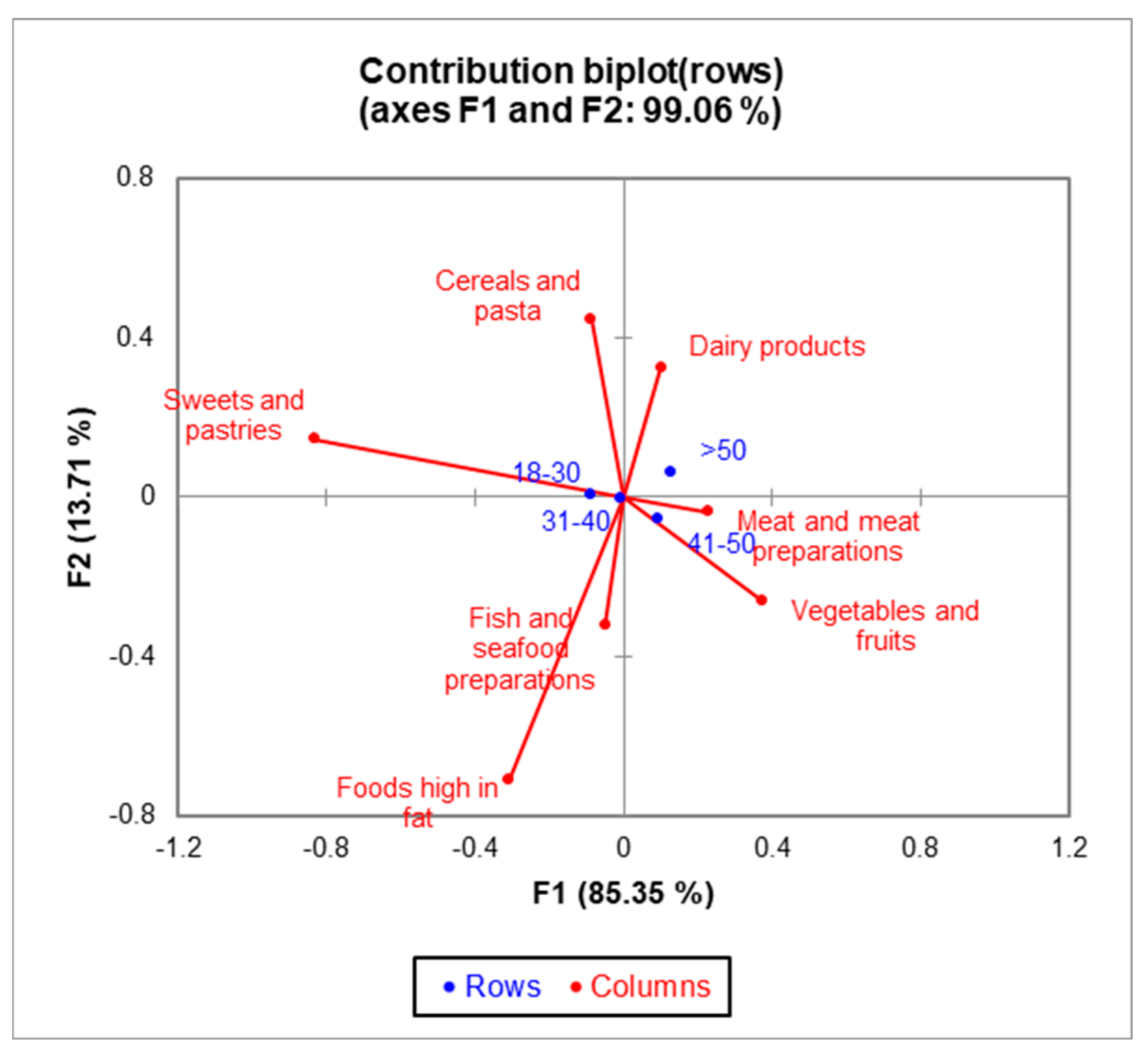

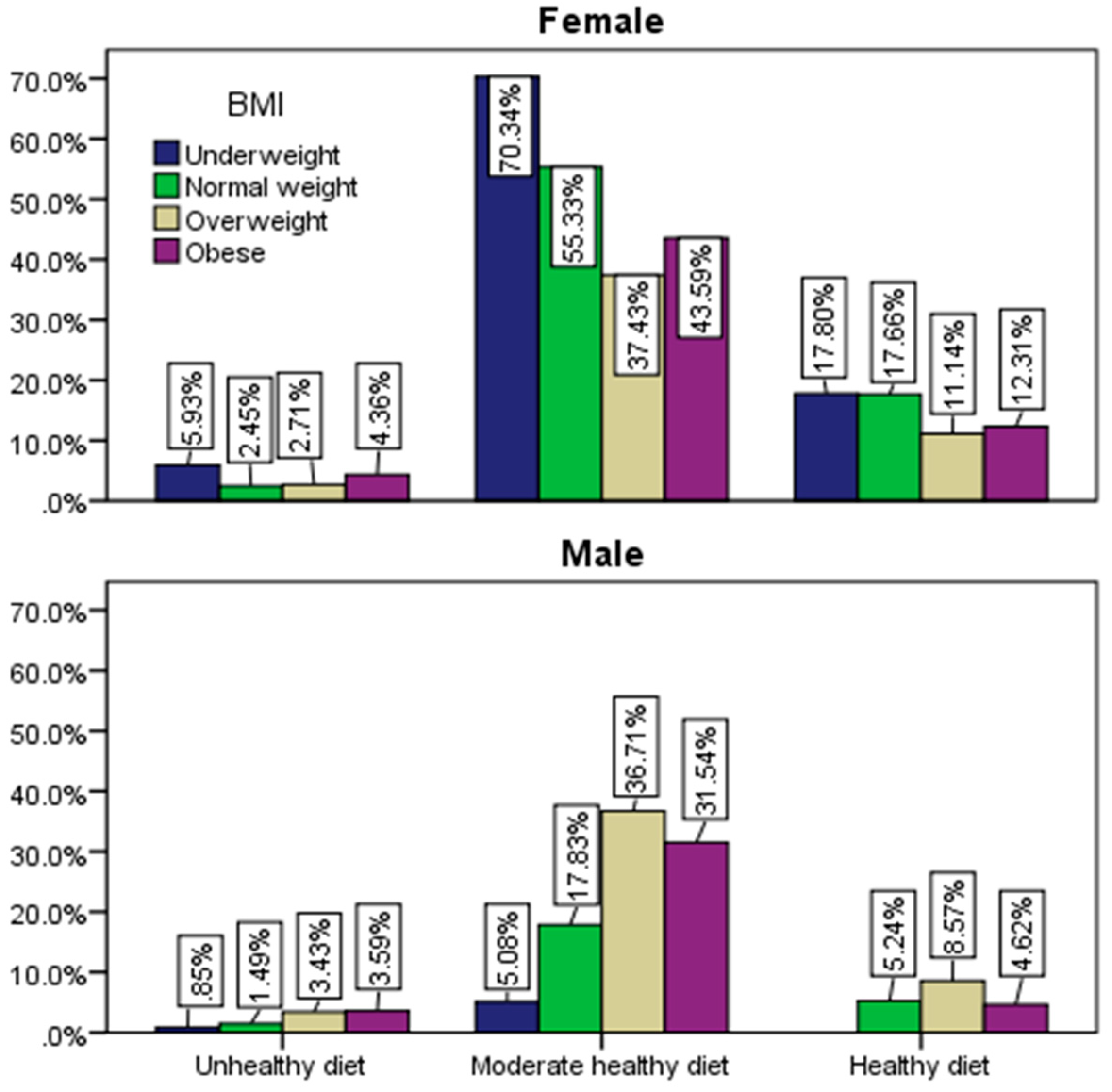

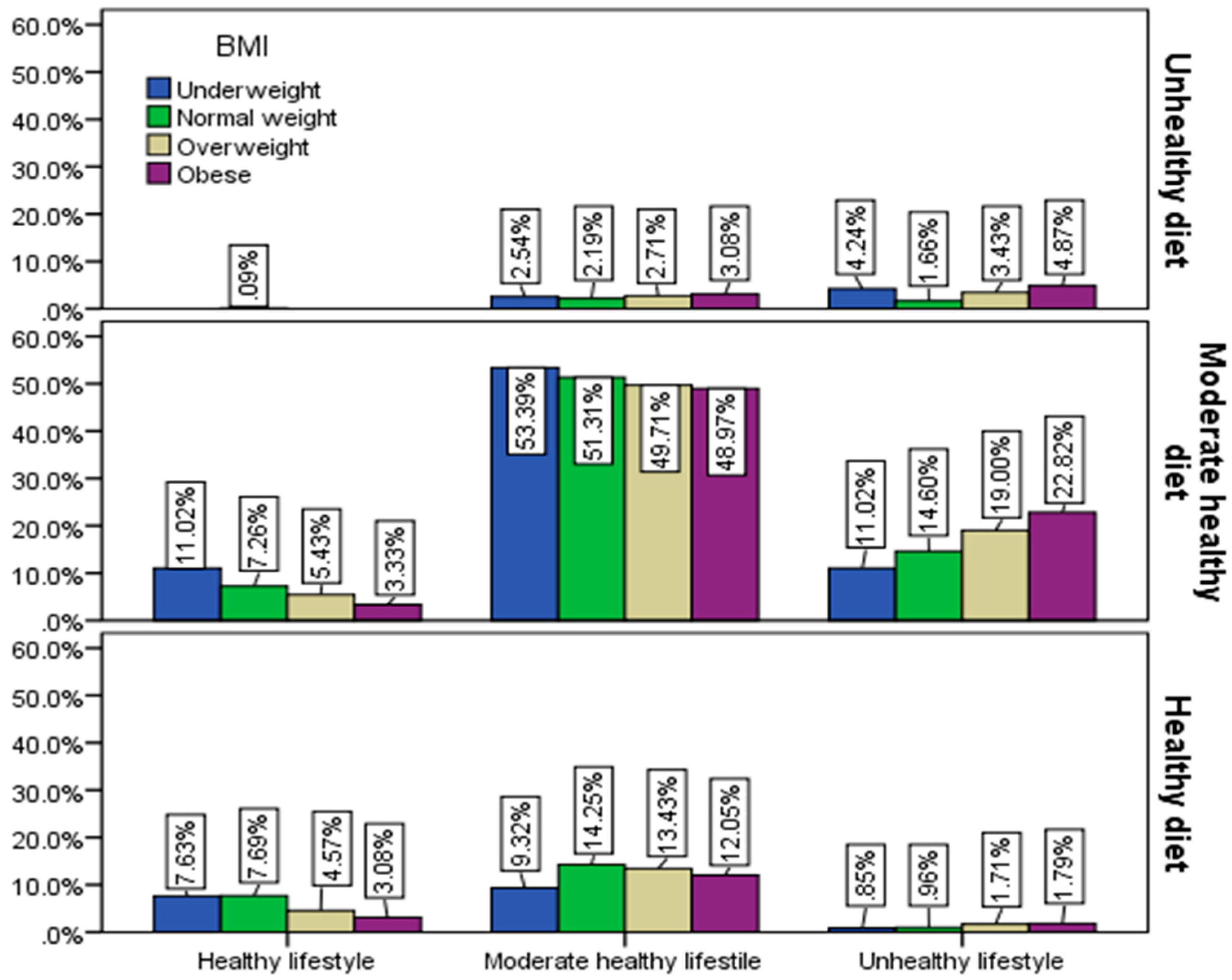

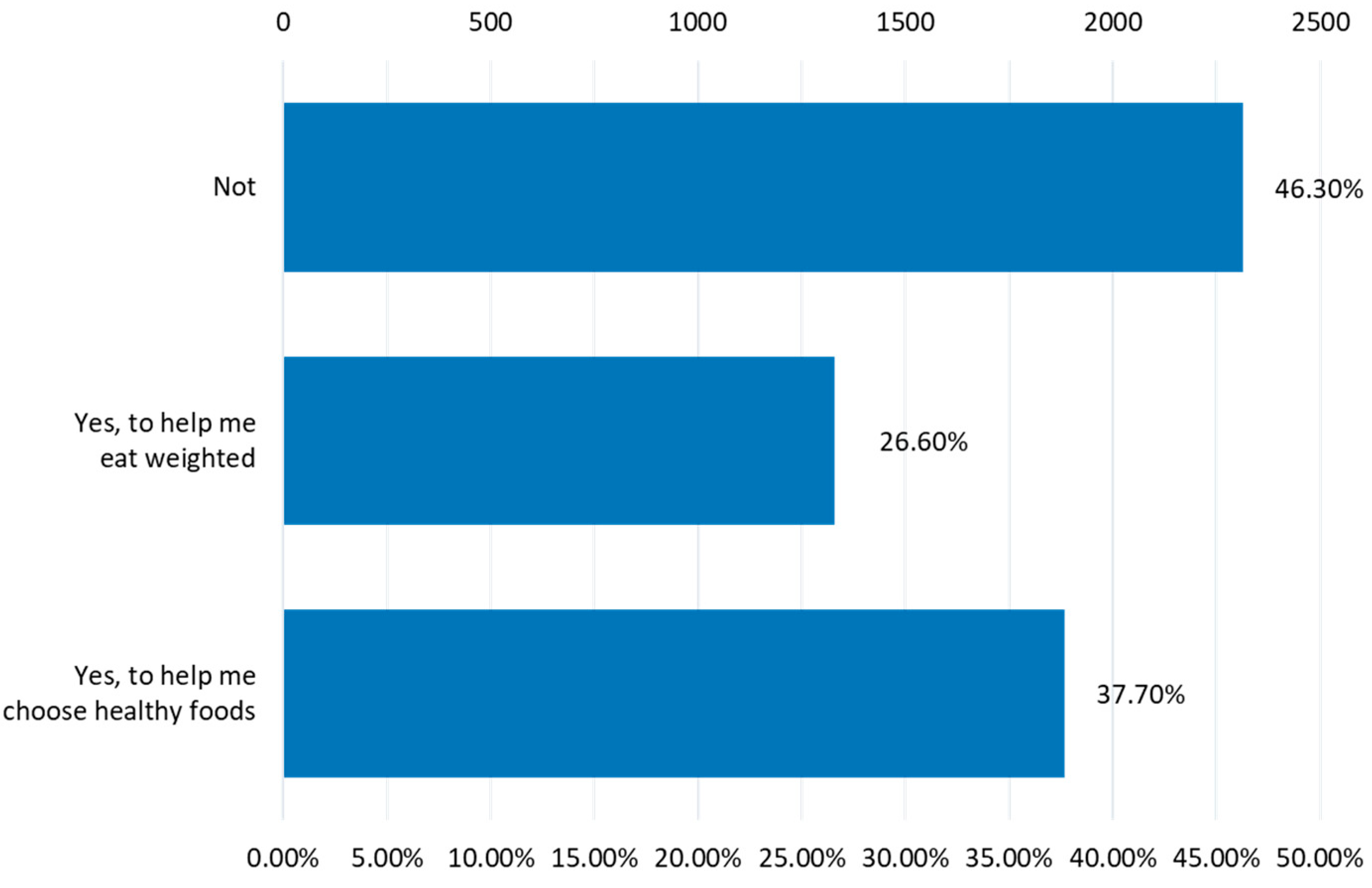

3.2. Adherence to a Healthy Diet

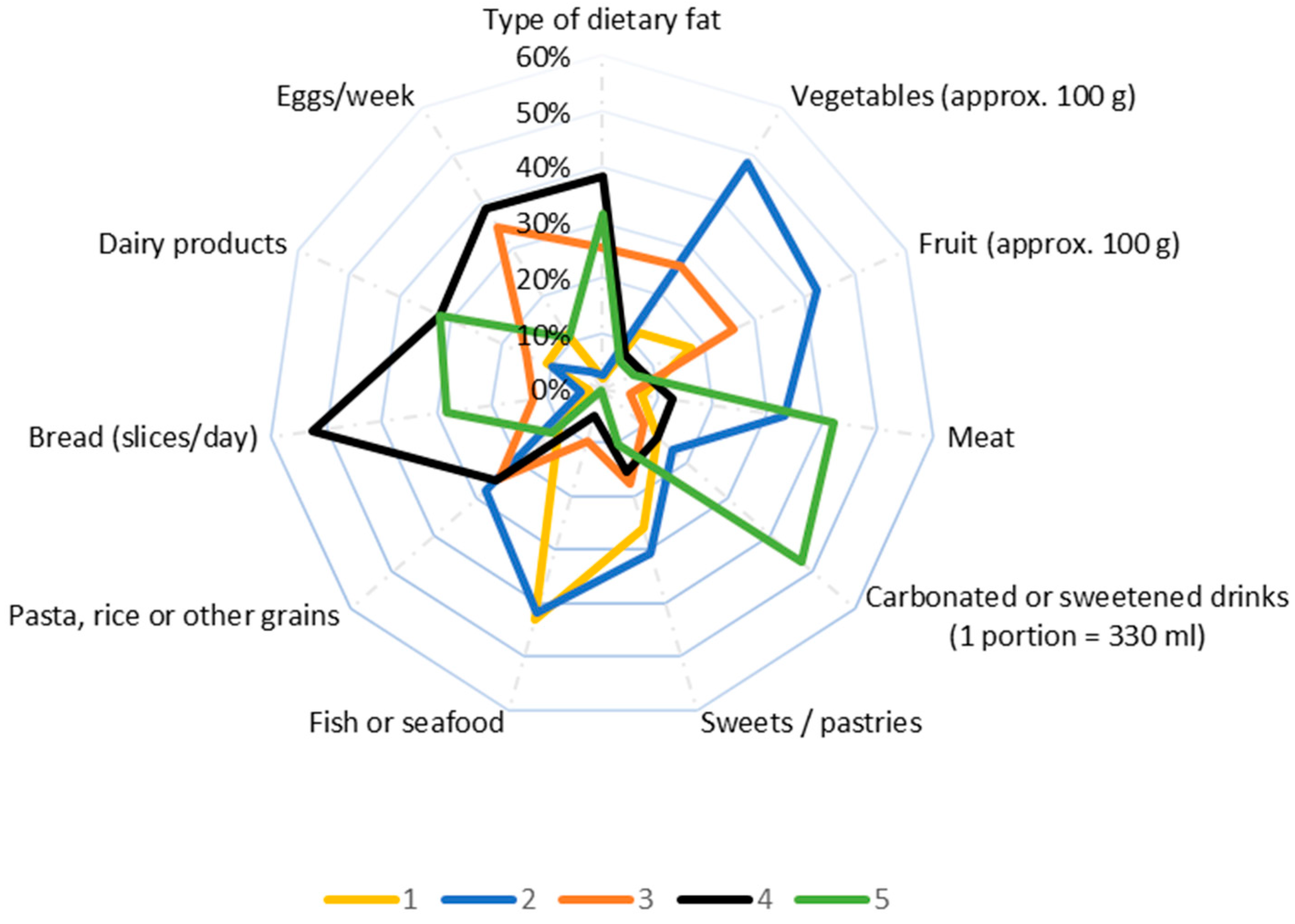

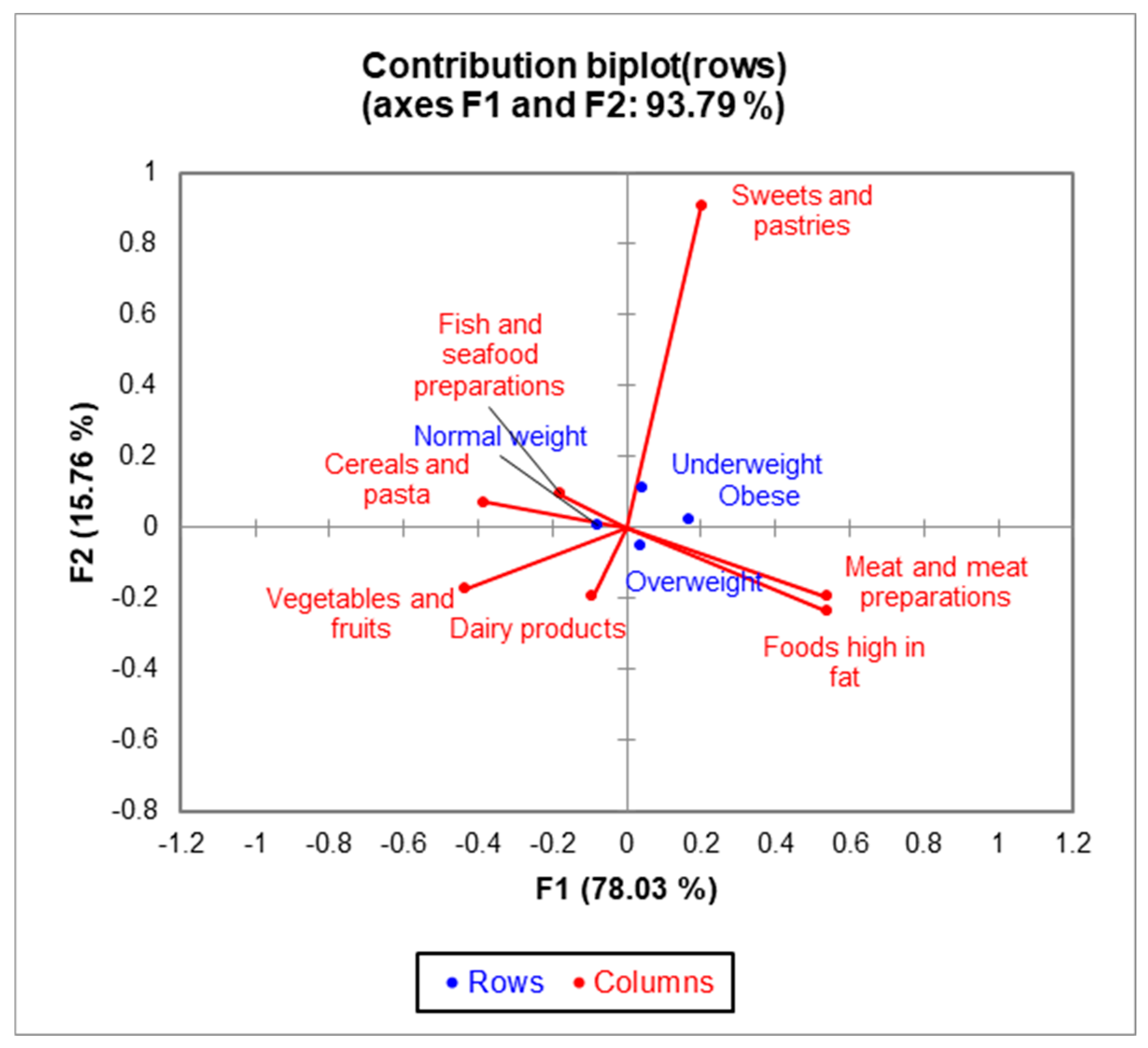

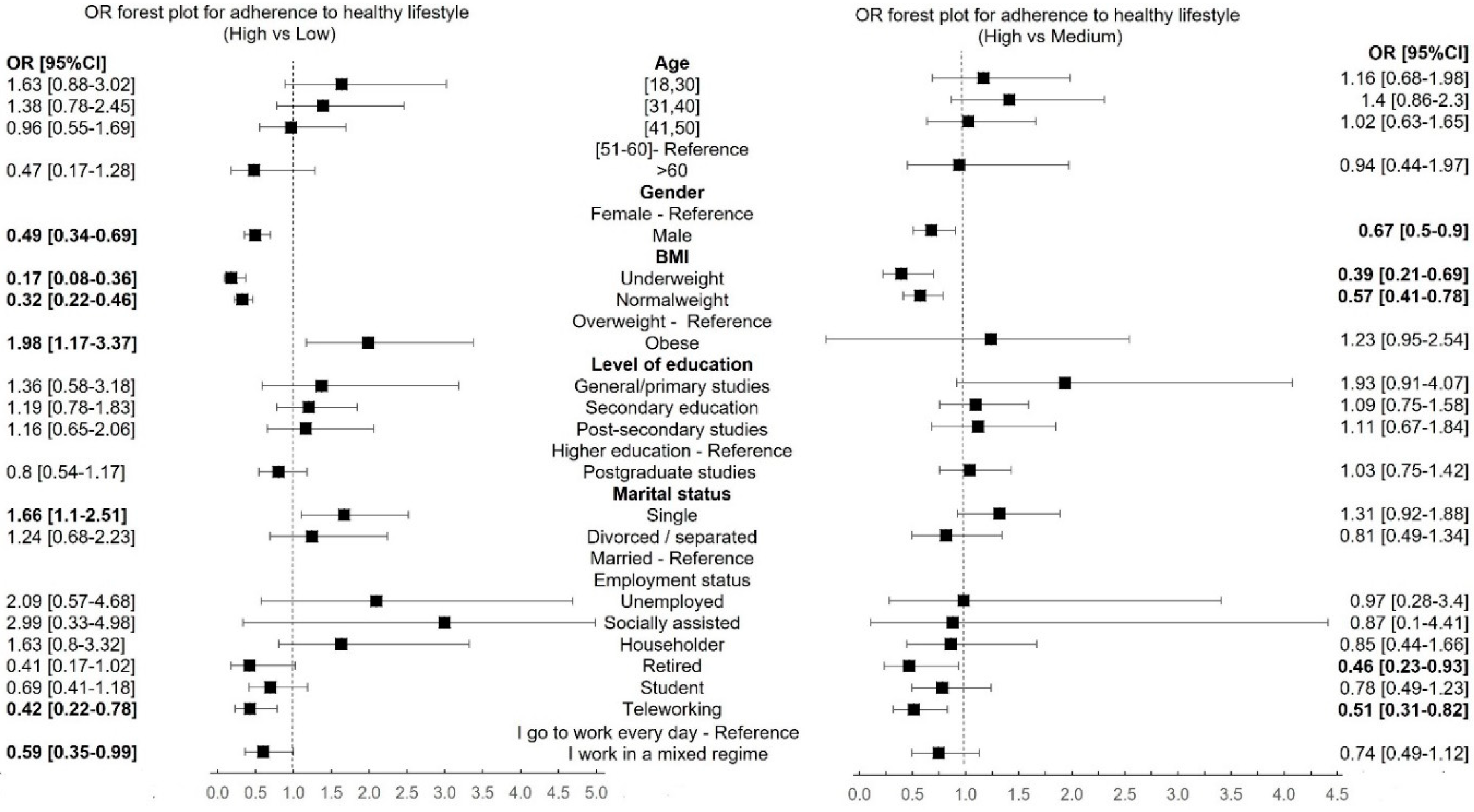

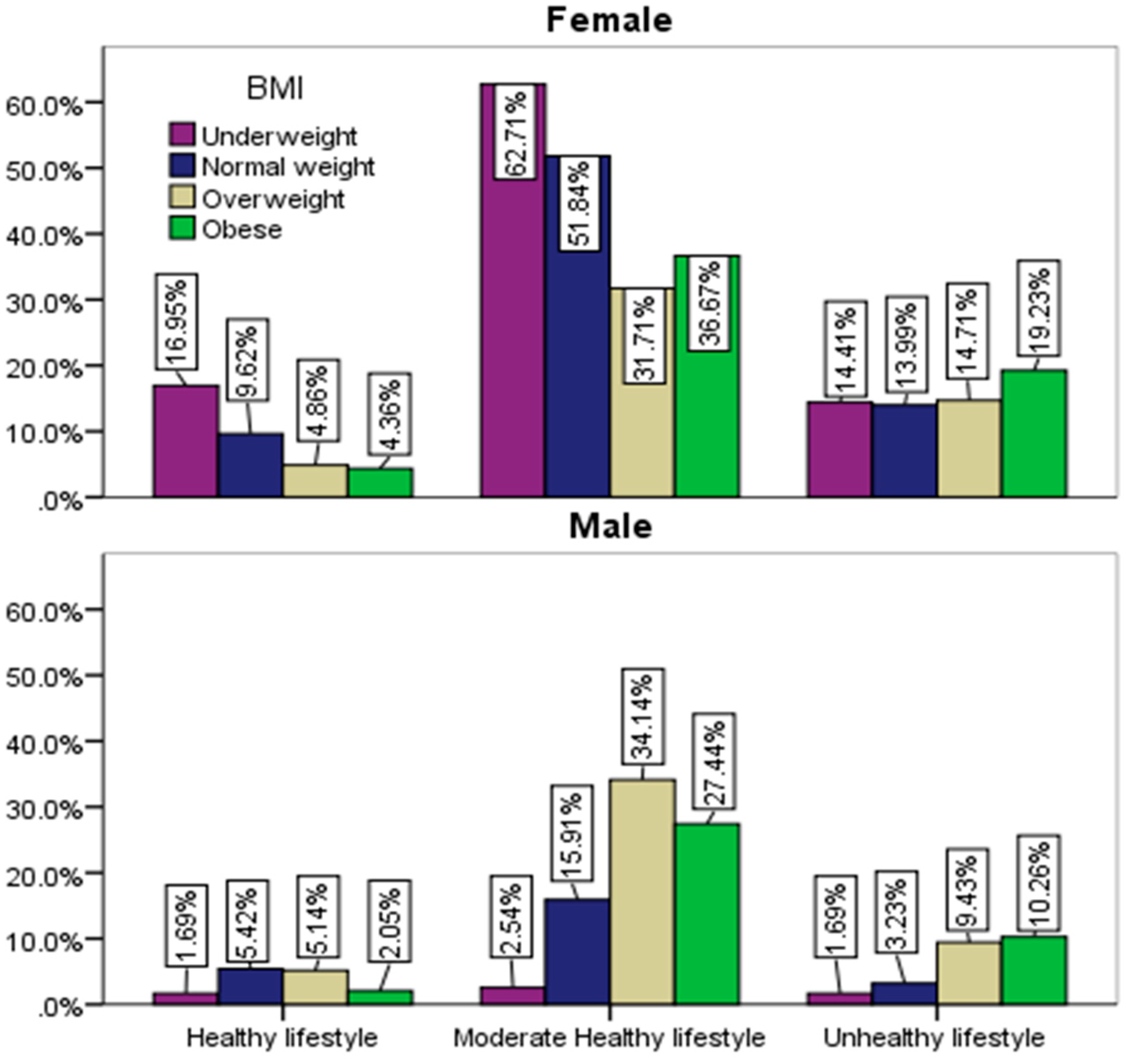

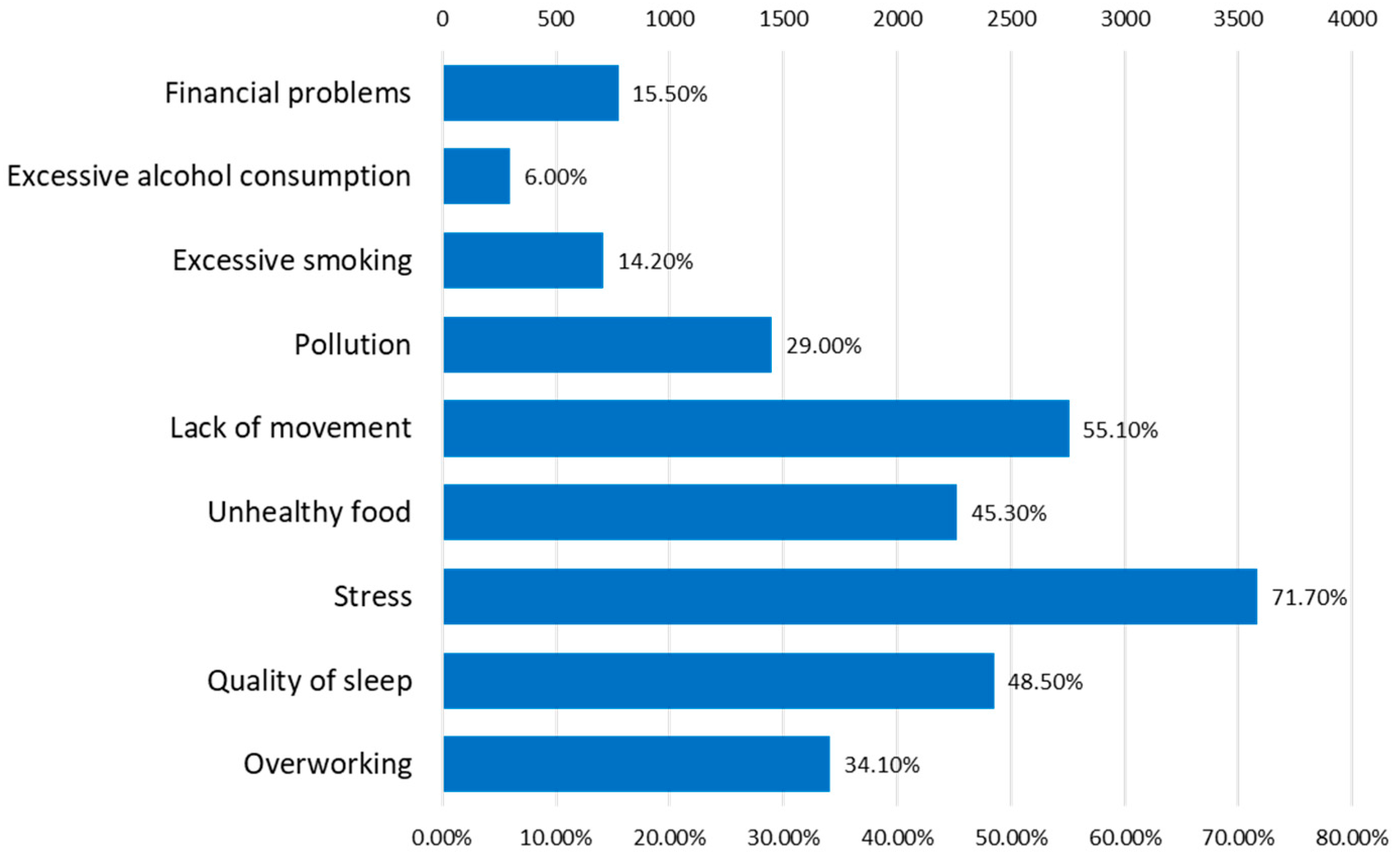

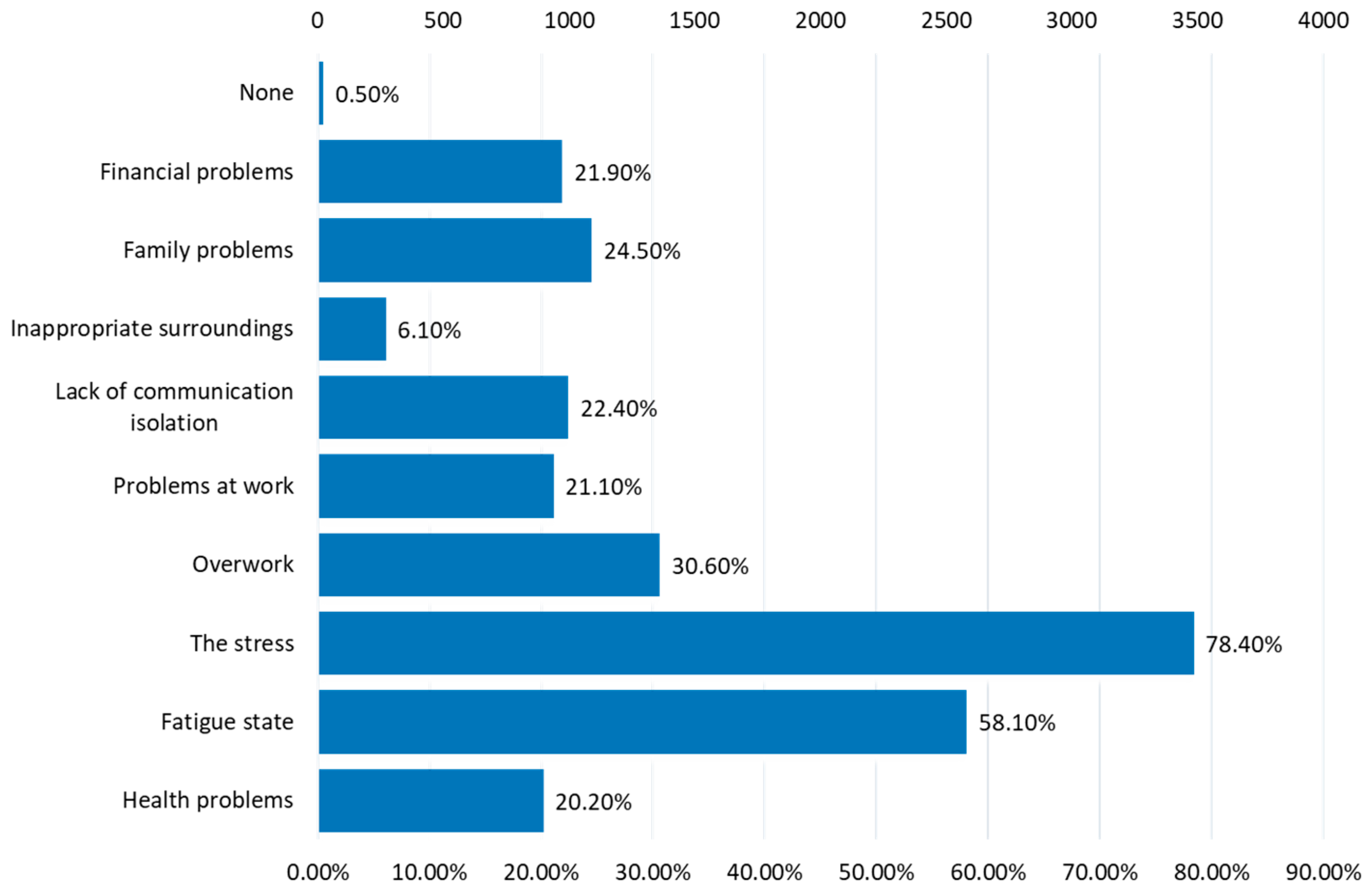

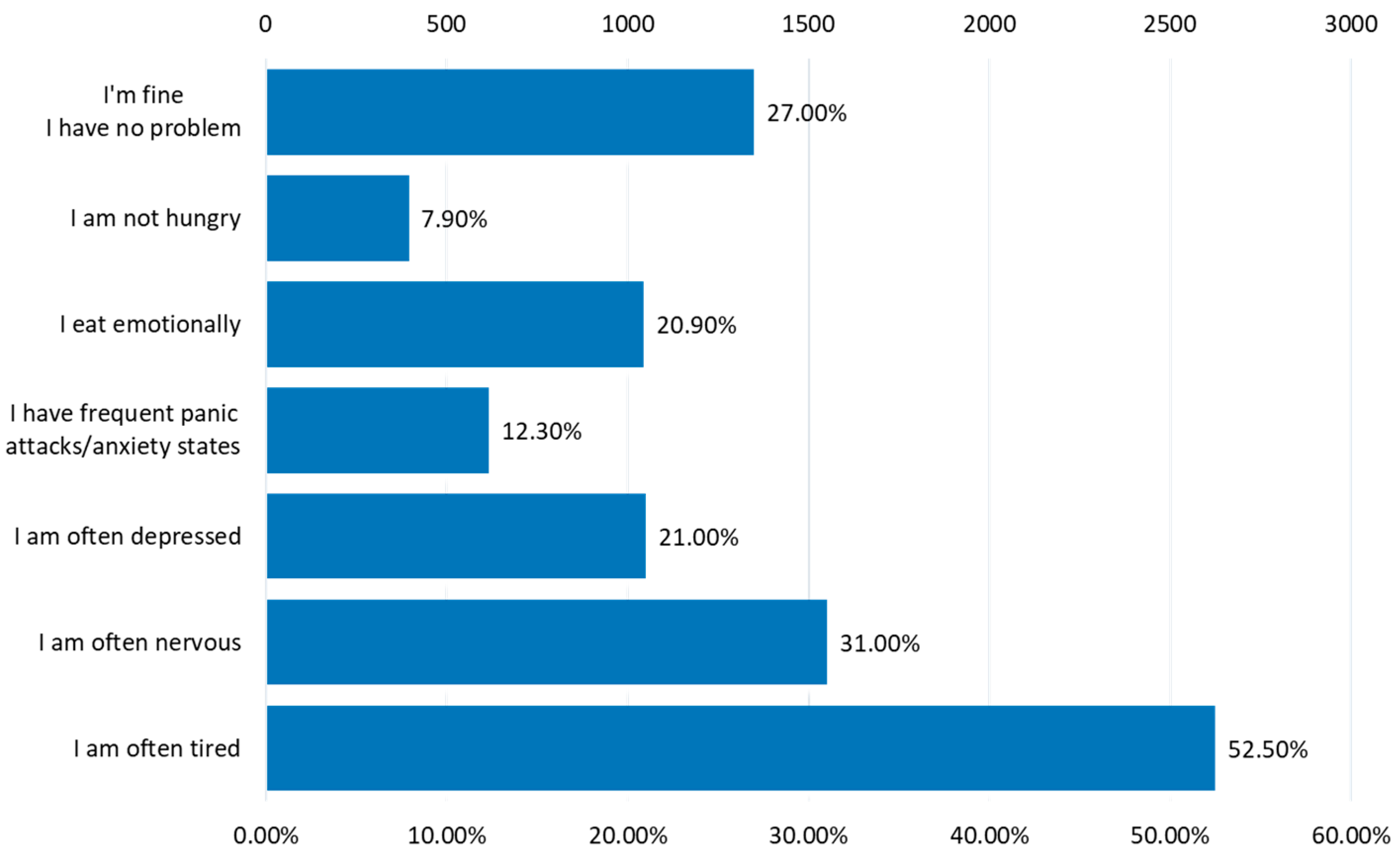

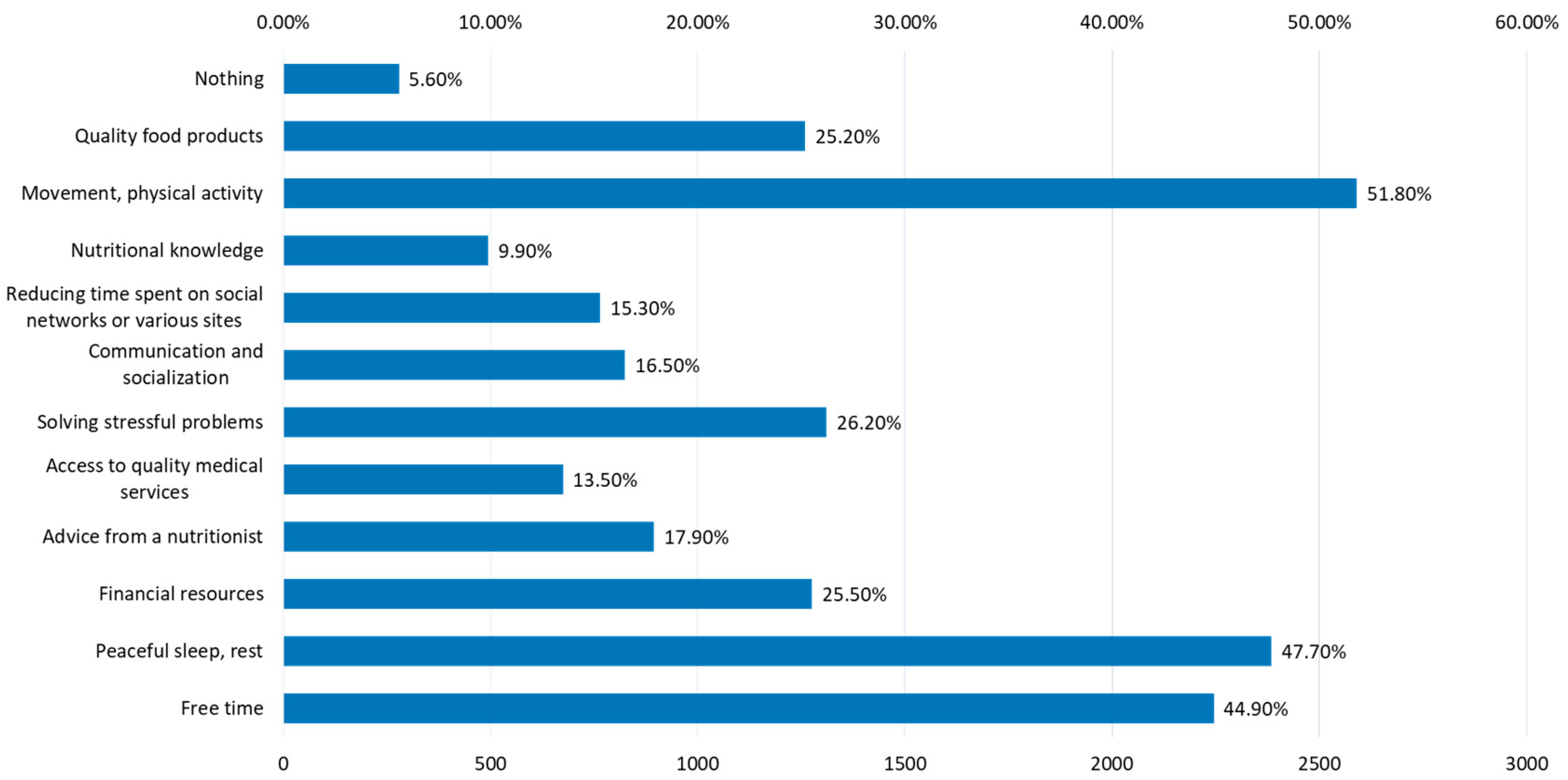

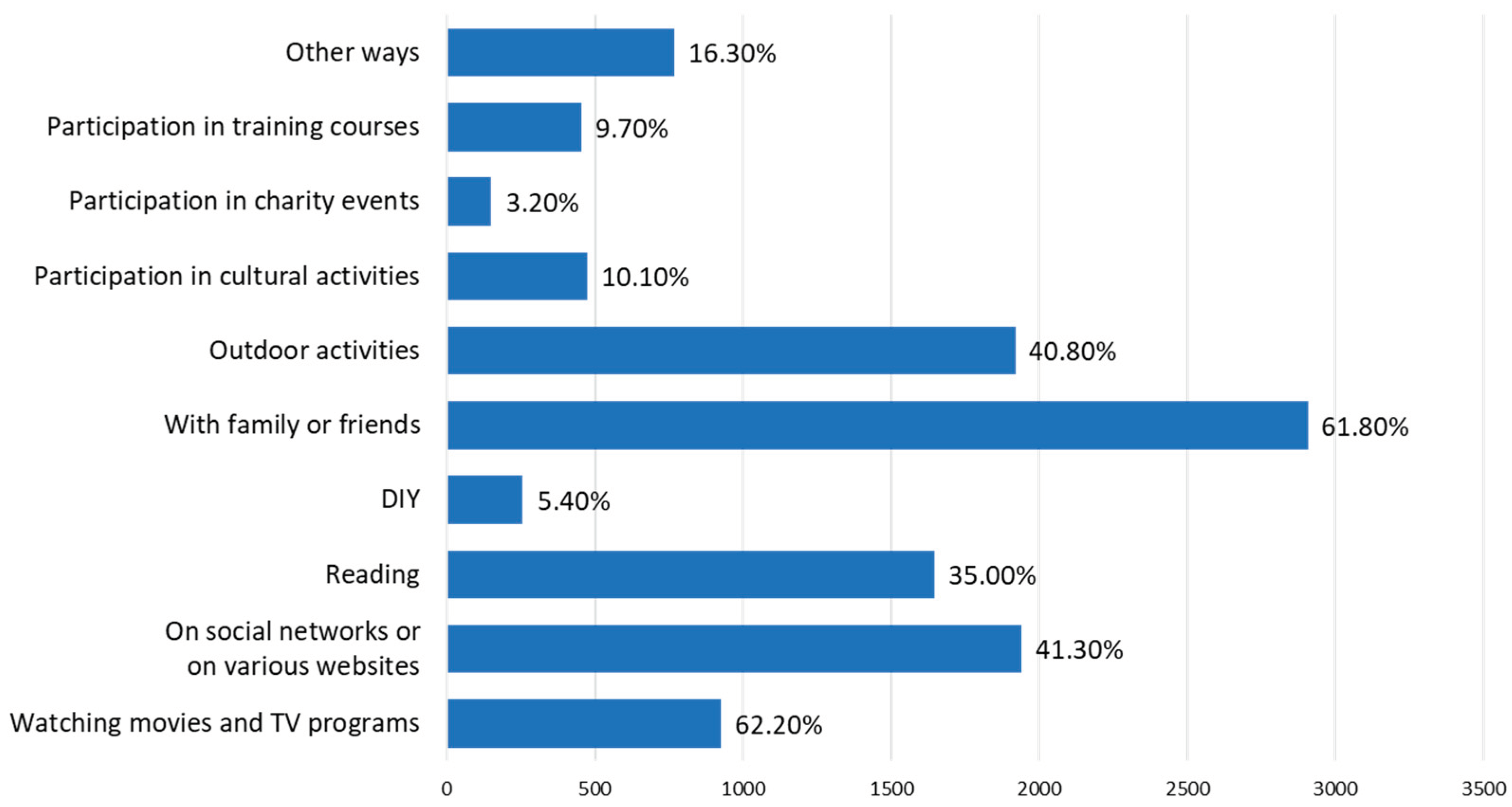

3.3. Eating Habits and Lifestyle

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ahmad Malik, J.; Ahmed, S.; Shinde, M.; Almermesh, M.H.S.; Alghamdi, S.; Hussain, A.; Anwar S. The Impact of COVID-19 On Comorbidities: A Review Of Recent Updates For Combating It. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022, 29(5):3586-3599. [CrossRef]

- Moccia, F.; Gerbino, A.; Lionetti, V.; Miragoli, M.; Munaron, L.M.; Pagliaro, P.; Pasqua, T.; Penna, C.; Rocca, C.; Samaja, M.; Angelone T. COVID-19-associated cardiovascular morbidity in older adults: a position paper from the Italian Society of Cardiovascular Researches. Geroscience, 2020, 42(4):1021-1049. [CrossRef]

- WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/353747/9789289057738-eng.pdf, accessed on 1.08.2023.

- https://www.era-learn.eu/network-information/networks/era-for-health; accessed on 1.08.2023.

- World Health Organization. Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic; accessed on 1.08.2023.

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard; https://covid19.who.int/; accessed on 5.08.2023.

- Svalastog, A.L.; Donev, D.; Jahren Kristoffersen, N.; Gajović, S. Concepts and definitions of health and health-related values in the knowledge landscapes of the digital society. Croat Med J., 2017, 58(6):431-435. [CrossRef]

- Ng, R.; Sutradhar, R.; Yao, Z.; Wodchis, W.P.; Rosella, L.C. Smoking, drinking, diet and physical activity-modifiable lifestyle risk factors and their associations with age to first chronic disease. Int J Epidemiol., 2020, 49(1):113-130. [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B. Globalization of diabetes: the role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care. 2011, 34(6):1249-57. PMID: 21617109. [CrossRef]

- Thavorn, K.; Maxwell, C.J.; Gruneir, A.; Bronskill, S.E.; Bai, Y.; Koné Pefoyo, A.J.; Petrosyan, Y.; Wodchis W.P. Effect of socio-demographic factors on the association between multimorbidity and healthcare costs: a population-based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017, 7(10):e017264. [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.D.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Kemnitz, J.W.; Klein, S.; Schoelle, D.A.; Speakman, J.R. Energy balance and its components: implications for body weight regulation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 95(4):989-94. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Michalak, M.; Agellon, L.B. Importance of Nutrients and Nutrient Metabolism on Human Health. Yale J Biol Med. 2018, 91(2):95-103.

- Choi, S.W.; Friso, S. Epigenetics: A New Bridge between Nutrition and Health. Adv Nutr. 2010, 1(1):8-16. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Araki, M.; Goto, S.; Hattori, M.; Hirakawa, M.; Itoh, M.; Katayama, T.; Kawashima, S.; Okuda, S.; Tokimatsu, T.; Yamanishi, Y. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36(Database issue):D480-4. [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J.L.; Lloyd, B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv Nutr. 2012, 3(4):506-16. [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Derito, C.M.; Liu, M.K.; He, X.; Dong, M.; Liu, R.H. Cellular antioxidant activity of common vegetables. J Agric Food Chem. 2010, 58(11):6621-9. [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M.; Boucher, B.A.; Cheung, A.M.; Beyene, J.; Shah, P.S. Fruit and vegetable intake and bone health in women aged 45 years and over: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int. 2011, 22(6):1681-93. [CrossRef]

- Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Ziani, K.; Mititelu, M.; Oprea, E.; Neacșu, S.M.; Moroșan, E.; Dumitrescu, D.-E.; Roșca, A.C.; Drăgănescu, D.; Negrei, C. Therapeutic Benefits and Dietary Restrictions of Fiber Intake: A State of the Art Review. Nutrients, 2022, 14, 2641; [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, Y.; Jeong, H.S.; Lee, J.; Sung, J. Effect of different cooking methods on the content of vitamins and true retention in selected vegetables. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2017, 27(2):333-342. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Chen, J.; Lv, F.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Ye, X. Domestic cooking methods affect the phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of purple-fleshed potatoes. Food Chem. 2016, 197 Pt B:1264-70. [CrossRef]

- Knecht, K.; Sandfuchs, K.; Kulling, S.E.; Bunzel, D. Tocopherol and tocotrienol analysis in raw and cooked vegetables: a validated method with emphasis on sample preparation. Food Chem. 2015, 169:20-7. [CrossRef]

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet; accesed on 14.09.2022.

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet, 2019, 393(10170):447-492; [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for The Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2020, 12(2):334. [CrossRef]

- Probst, Y.C.; Guan, V.X.; Kent, K. Dietary phytochemical intake from foods and health outcomes: A systematic review protocol and preliminary scoping. BMJ Open. 2017; 7:e013337. [CrossRef]

- Ionita, A.C.; Mititelu, M.; Moroşan, E. Analysis of heavy metals and organic pollutants from some Danube river fishes, Farmacia, 2014, 62(2):299-305.

- Mititelu, M.; Moroşan, E.; Neacsu, S.M.; Ioniţă, E.I. Research regarding the pollution degree from romanian Black Sea coast. Farmacia, 2018, 66, 1059–1063. http://doi.org/10.31925/farmacia.2018.6.20.

- Mititelu, M.; Nicolescu, T.O.; Ioniţă, C.A.; Nicolescu, F. Study of Heavy Metals and Organic Polluants From Some Fisches of Danube River, Journal of Enviromental Protection and Ecology, 2012, 13(2A):869-874.

- Mititelu, M.; Nicolescu, T.O.; Ioniţă, C.A.; Nicolescu, F. Heavy Metals Analisys in Some Wild Edible Mushrooms. J. Environmental Prot. Ecol. 2012, 13, 875–879.

- Mititelu, M.; Ioniţă, A.C.; Moroşan, E. Research regarding integral processing of mussels from Black Sea. Farmacia 2014, 62, 625–632.

- Mititelu, M.; Neacsu, S.M.; Oprea, E.; Dumitrescu, D.-E.; Nedelescu, M.; Drăgănescu, D.; Nicolescu, T.O.; Rosca, A.C.; Ghica, M. Black Sea Mussels Qualitative and Quantitative Chemical Analysis: Nutritional Benefits and Possible Risks through Consumption. Nutrients, 2022, 14, 964. [CrossRef]

- Ioniţă, A.C.; Ghica, M.; Moroşan, E.; Nicolescu, F.; Mititelu, M. In vitro effects of some synthesized aminoacetanilide n’-substituted on human leukocytes separated from peripheral blood, Farmacia, 2019, 67(4), 684-690. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.; Holt, D.W. Substandard drugs: a potential crisis for public health. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014, 78(2):218-43. [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.F. Sustaining Health-Protective Behaviors Such as Physical Activity and Healthy Eating. JAMA. 2018, 320(7):639-640. [CrossRef]

- Jakicic, J.M.; Rogers, R.J.; Davis, K.K.; Collins, K.A. Role of physical activity and exercise in treating patients with overweight and obesity. Clin. Chem. 2018, 64, 99–107. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Moon, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kong, M.H.; Oh, Y.H. Sedentary Lifestyle: Overview of Updated Evidence of Potential Health Risks. Korean J Fam Med. 2020, 41(6):365-373. [CrossRef]

- Rees-Punia, E.; Evans, E.M.; Schmidt, M.D.; Gay, J.L.; Matthews, C.E.; Gapstur, S.M.; Patel, A.V. Mortality Risk Reductions for Replacing Sedentary Time With Physical Activities. Am J Prev Med. 2019; 56(5):736-741. [CrossRef]

- Mullane, S.L.; Buman, M.P.; Zeigler, Z.S.; Crespo, N.C.; Gaesser, G.A. Acute effects on cognitive performance following bouts of standing and light-intensity physical activity in a simulated workplace environment. J Sci Med Sport. 2017, 20(5):489-493. [CrossRef]

- Magnon, V.; Vallet, G.T.; Auxiette, C. Sedentary Behavior at Work and Cognitive Functioning: A Systematic Review. Front Public Health. 2018, 31;6:239. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th Edition, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, December 2010. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01/DietaryGuidelines2010.pdf, accesed on 14.09.2022.

- Jequier, E.; Constant, F. Water as an essential nutrient: The physiological basis of hydration. Eur. J. Nutr. 2010, 64:115–123. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, I.; Serra-Prat, M.; Yébenes, J.C. The Role of Water Homeostasis in Muscle Function and Frailty: A Review. Nutrients. 2019; 11(8):1857. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Tanaka, A.; Yasui, M.; Nishihira, J.; Murayama, N. Effect of Increased Daily Water Intake and Hydration on Health in Japanese Adults. Nutrients. 2020, 12(4):1191. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, L.E.; Ganio, M.S.; Casa, D.J.; Lee, E.C.; MacDermott, B.P.; Klau, J.F.; Jimenez, L.; Lieberman, H.R. Mild dehydration affects mood in healthy young women. J. Nutr. 2012, 142:328–388. [CrossRef]

- Benton, D.; Burgess, N. The effect of the consumption of water on the memory and attention of children. Appetite. 2009, 53:143–146. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, X.; Qin, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Huang, H.; Xu, Y. Association between total water intake and dietary intake of pregnant and breastfeeding women in China: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019, 19(1):172. [CrossRef]

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Whiton, K.; Albert, S. M.; Alessi, C.; Bruni, O.; DonCarlos, L.; Hazen, N.; Herman, J.; Katz, E. S.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; Neubauer, D. N.; O'Donnell, A. E.; Ohayon, M.; Peever, J.; Rawding, R.; Sachdeva, R. C.; Setters, B.; Vitiello, M. V.; Ware, J. C.; Adams Hillard, P. J. National Sleep Foundation's sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep health, 2015, 1(1), 40–43. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovskiy, V.V. Sleep, recovery, and metaregulation: explaining the benefits of sleep. Nat Sci Sleep. 2015, 7:171-84. [CrossRef]

- Cirelli, C.; Tononi, G. Is sleep essential? PLoS Biol. 2008, 6(8):e216. [CrossRef]

- Vassalli, A.; Dijk, D.J. Sleep function: current questions and new approaches. Eur J Neurosci. 2009, 29(9):1830-41. [CrossRef]

- Passarino, G.; De Rango, F.; Montesanto, A. Human longevity: Genetics or Lifestyle? It takes two to tango. Immun Ageing. 2016, 13:12. [CrossRef]

- Limpens, M.A.M.; Asllanaj, E.; Dommershuijsen, L.J.; Boersma, E.; Ikram, M.A.; Kavousi, M.; Voortman, T. Healthy lifestyle in older adults and life expectancy with and without heart failure. Eur J Epidemiol, 2022, 37, 205–214; [CrossRef]

- Chudasama, Y.V.; Khunti, K.; Gillies, C.L.; Dhalwani, N.N.; Davies, M.J.; Yates, T.; Zaccardi, F. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy in people with multimorbidity in the UK Biobank: A longitudinal cohort study. PLoS Med, 2020, 17(9): e1003332. [CrossRef]

- Reichenberger, J.; Schnepper, R.; Arend, A.K.; Blechert, J. Emotional eating in healthy individuals and patients with an eating disorder: evidence from psychometric, experimental and naturalistic studies. Proc Nutr Soc. 2020, 79(3):290-299. [CrossRef]

- European Commission - State of Health in the EU · România · Profilul de țară din 2021 în ceea ce privește sănătatea; https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/2021_chp_romania_romanian.pdf; accessed on 10.05.2023.

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol., 1975, 28 (4): 563-575.

- Yusoff, M.S.B. ABC of Content Validation and Content Validity Index Calculation, Educ. Med. J., 2019, 11, 49-54.

- Connelly, L. M. Pilot studies. Medsurg Nursing, 2008, 17(6):411-2.

- Viechtbauer, W.; Smits, L.; Kotz, D.; Budé, L.; Spigt, M.; Serroyen, J.; Crutzen, R. A simpleformula for the calculation of sample size in pilot studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2015, 68(11):1375-1379. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 1974, 39(1):31-36. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. A note on the multiplying factors for various χ2 approximations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 1954, 16(2):296-298.

- Bonkat, G.; Bartoletti, R.; Bruyére, F.; Cai, T.; Geerlings, S.E.; Köves, B.; Schubert, S.; Wagenlehner, F. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections 2020. In European Association of Urology Guidelines. 2020 Edition. (Vol. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Amsterdam 2020). European Association of Urology Guidelines Office. http://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-infections/ accessed on 05.05.2023.

- Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Mititelu, M.; Musuc, A.M.; Oprea, E.; Ziani, K.; Neacșu, S.M.; Grigore, N.D.; Negrei, C.; Dumitrescu, D.-E.; Mireșan, H.; Roncea, F.N.; Ozon, E.A.; Măru, N.; Drăgănescu, D.; Ghica, M. Honey and Other Beekeeping Products Intake among the Romanian Population and Their Therapeutic Use. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9649. [CrossRef]

- Năstăsescu, V.; Mititelu, M.; Stanciu, T.I.; Drăgănescu, D.; Grigore, N.D.; Udeanu, D.I.; Stanciu, G.; Neacșu, S.M.; Dinu-Pîrvu, C.E.; Oprea, E.; Ghica, M. Food Habits and Lifestyle of Romanians in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2022, 14, 504. [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Addinsoft (2020) XLSTAT Statistical and Data Analysis Solution. New York. https://www.xlstat.com.

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S. Fourth Edition. Springer, New York., 2002, ISBN 0-387-95457-0.

- Branca, F.; Nikogosian, H.; Lobstein, T. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. In The Challenge of Obesity in the WHO European Region and the Strategies for Response; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007; ISBN 9789289014083.

- Ashwell, M.; Gibson, S. Waist-to-height ratio as an indicator of early health risk: Simpler and more predictive than using a matrix based on BMI and waist circumference. BMJ Open, 2016, 6, e010159. [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.M.; Webster, J.; McKenzie, B.; Geldsetzer, P.; Manne-Goehler, J.; Andall-Brereton, G.; Houehanou, C.; Houinato, D.; Gurung, M.S.; Bicaba, B.W.; McClure, R.W.; Supiyev, A.; Zhumadilov, Z.; Stokes, A.; Labadarios, D.; Sibai, A.M.; Norov, B.; Aryal, K.K.; Karki, K.B.; Kagaruki, G.B.; Mayige, M.T.; Martins, J.S.; Atun, R.; Bärnighausen, T.; Vollmer, S.; Jaacks, L.M. Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables Among Individuals 15 Years and Older in 28 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J Nutr. 2019; 149(7):1252-1259. [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D.; Sogari, G.; Mora, C. Explaining Vegetable Consumption among Young Adults: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Nutrients. 2015; 7(9):7633-50. [CrossRef]

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Nutritional_habits_statistics&oldid=572524; accesed on 14.06.2023.

- Mititelu, M; Stanciu, T.I.; Udeanu, D.I.; Popa, D.E.; Drăgănescu, D.; Cobelschi, C.; Grigore, N.D.; Pop, A.L.; Ghica, M. The impact of covid-19 lockdown on the lifestyle and dietary patterns among romanian population, Farmacia, 2021, (69)1, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Nitu, I.; Rus, V.A.; Sipos, R.S.; Nyulas, T.; Cherhat, M.P.; Ruta, F.; Nitu, C.C. Assessment of Eating Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic Period. A Pilot Study. Journal of Interdisciplinary Medicine, June 2021, Volume 6/Issue 2/ ISSN: 2501 – 8132.

- Nsiah-Asamoah, C.N.A.; Buxton, D.N.B. Hydration and water intake practices of commercial long-distance drivers in Ghana: what do they know and why does it matter? Heliyon. 2021; 7(3):e06512. [CrossRef]

- Haghighatdoost, F.; Feizi, A.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Rashidi-Pourfard, N.; Keshteli, A. H.; Roohafza, H.; Adibi, P. Drinking plain water is associated with decreased risk of depression and anxiety in adults: Results from a large cross-sectional study. World Journal of Psychiatry, 2018, 8(3), 88–96. [CrossRef]

- Lotrean, L.M.; Ionut, C.; de Vries, H. Tobacco use among Romanian youth. Salud Publica Mex. 2006; 48 Suppl 1:S107-12. [CrossRef]

- Mota, M.; Popa, S.G.; Mota, E.; Mitrea, A.; Catrinoiu, D.; Cheta, D.M.; Guja, C.; Hancu, N.; Ionescu-Tirgoviste, C.; Lichiardopol, R.; Mihai, B.M.; Popa, A.R.; Zetu, C.; Bala, C.G.; Roman, G.; Serafinceanu C.; Serban, V.; Timar, R.; Veresiu, I.A.; Vlad, A.R. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and prediabetes in the adult Romanian population: PREDATORR study. J Diabetes. 2016; 8(3):336-44. [CrossRef]

- Popa, S.; Mota, M.; Popa, A.; Mota, E.; Timar, R.; Serafinceanu, C.; Cheta, D.; Graur, M.; Hancu N. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and its association with cardiometabolic factors and kidney function in the adult Romanian population: The PREDATORR study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019; 13(1):596-602. [CrossRef]

- Moţa, E.; Popa, S.G.; Mota, M.; Mitrea, A.; Penescu, M.; Tuţă, L.; Serafinceanu, C.; Hâncu, N.; Gârneaţă, L.; Verzan, C.; Lichiardopol, R.; Zetu, C.; Căpuşă, C.; Vlăduţiu, D.; Guja, C.; Catrinoiu, D.; Bala, C.; Roman, G.; Radulian, G.; Timar, R.; Mihai, B. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and its association with cardio-metabolic risk factors in the adult Romanian population: the PREDATORR study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015; 47(11):1831-8. [CrossRef]

- Searchinger, T.; Hanson, C.; Ranganathan, J.; Lipinski, B.; Waite, R.; Winterbottom, R.; et al. World Resources Report 2013–14: Interim Findings. Creating a Sustainable Food Future: Interim Findings. A menu of solutions to sustainably feed more than 9 billion people by 2050, World Resources Institute (WRI), 2014. https://www.wri.org/research/creating-sustainable-food-future-interim-findings.

| Characteristics | Total population - n (%) | Male - n (%) | Female - n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4704 (100) | 1568 (33.3) | 3136 (66.7) | |

| Age (years); p<0.0001 | |||

| 18-30 | 1756 (37.3) | 528 (33.7) | 1228 (39.2) |

| 31-40 | 1136 (24.2) | 354 (22.6) | 782 (24.9) |

| 41-50 | 1034 (22) | 344 (21.9) | 690 (22) |

| 51-60 | 534 (11.3) | 204 (13) | 324 (10.5) |

| >60 | 246 (5.2) | 138 (8.8) | 1008 (3.4) |

| Residence areas; p=0.0002 | |||

| Urban areas | 3648 (77.6) | 1144 (72.9) | 2504 (79.8) |

| Rural areas | 1056 (22.4) | 424 (23.1) | 632 (20.2) |

| Level of education; p<0.0001 | |||

| General/primary studies | 298 (6.3) | 154 (9.8) | 144 (4.6) |

| Secondary education | 1090 (23.2) | 392 (25.0) | 698 (22.3) |

| Post-secondary studies | 420 (8.9) | 132 (8.4) | 288 (9.2) |

| Higher education | 1616 (34.4) | 528 (33.7) | 1088 (34.7) |

| Postgraduate studies | 1280 (27.2) | 362 (23.1) | 918 (29.3) |

| Marital status; p=0.0049 | |||

| Single | 1688 (35.9) | 634 (53.7) | 1054 (59.6) |

| Divorced/separated | 306 (6.5) | 92 (5.9) | 214 (6.8) |

| Married | 2710 (57.6) | 842 (40.4) | 1868 (33.6) |

| Employment status; p<0.0001 | |||

| Unemployed | 78 (1.7) | 34 (2.2) | 44 (1.4) |

| Socially assisted | 26 (0.6) | 10 (0.6) | 16 (0.5) |

| Householder | 312 (6.6) | 36 (2.3) | 276 (8.8) |

| Retired | 270 (5.7) | 140 (8.9) | 130 (4.1) |

| Student | 838 (17.8) | 210 (13.4) | 628 (20) |

| Teleworking | 274 (5.8) | 92 (5.9) | 182 (5.8) |

| Going to work every day | 2406 (51.1) | 848 (54.1) | 1558 (49.7) |

| Mixed working regime | 500 (10.6) | 198 (12.6) | 302 (9.6) |

| Body mass index (BMI); p<0.0001 | |||

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 2288 | 562 (35.8) | 1726 (55.0) |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 1400 | 682 (43.5) | 718 (22.9) |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 236 | 14 (0.9) | 222 (7.1) |

| Obese (≥30) | 780 | 310 (19.8) | 470 (15.0) |

|

Variable |

Healthy diet |

Moderate healthy diet |

Unhealthy diet |

p-value Chi-squared test |

|||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 974 | 20.7 | 3476 | 73.9 | 234 | 5.4 | |

| Age | |||||||

| 18-30 | 292 | 30 | 1334 | 38.4 | 130 | 51.2 | <0.0001 |

| 31-40 | 270 | 27.7 | 810 | 23.3 | 56 | 22 | |

| 41-50 | 222 | 22.8 | 766 | 22 | 44 | 17.3 | |

| 51-60 | 106 | 10.9 | 408 | 11.7 | 20 | 7.9 | |

| >60 | 84 | 8.6 | 158 | 4.6 | 4 | 1.6 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| F | 698 | 71.7 | 2296 | 66.1 | 142 | 55.9 | 0.0020 |

| M | 276 | 28.3 | 1180 | 33.9 | 112 | 44.1 | |

| BMI | |||||||

| Underweight | 42 | 4.3 | 178 | 5.1 | 16 | 6.2 | 0.0102 |

| Normal weight | 524 | 53.8 | 1674 | 48.1 | 90 | 35.4 | |

| Overweight | 276 | 28.3 | 1038 | 29.8 | 86 | 33.8 | |

| Obese | 132 | 13.6 | 586 | 16.8 | 62 | 24.4 | |

| Residence areas | |||||||

| Urban | 788 | 80.9 | 2668 | 76.8 | 96 | 75.6 | 0.1315 |

| Rural | 186 | 19.1 | 808 | 23.2 | 62 | 24.4 | |

| Level of education | |||||||

| General/primary studies | 36 | 3.7 | 248 | 7.2 | 14 | 5.5 | 0.0087 |

| Secondary education |

202 | 20.7 | 818 | 23.5 | 70 | 27.5 | |

| Post-secondary studies | 84 | 8.6 | 300 | 8.6 | 36 | 14.2 | |

| Higher education |

344 | 35.3 | 1204 | 34.6 | 68 | 26.9 | |

| Postgraduate studies | 308 | 31.6 | 906 | 26.1 | 66 | 25.9 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single | 314 | 32.2 | 1254 | 36.1 | 120 | 47.2 | 0.0394 |

| Divorced/separated | 64 | 6.6 | 228 | 6.5 | 14 | 5.6 | |

| Married | 596 | 61.2 | 1994 | 57.4 | 120 | 47.2 | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Unemployed | 8 | 0.8 | 64 | 1.8 | 6 | 2.4 | 0.0038 |

| Socially assisted | 10 | 1 | 16 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Householder | 68 | 6.9 | 222 | 6.4 | 22 | 8.7 | |

| Retired | 84 | 8.6 | 182 | 5.2 | 4 | 1.6 | |

| Student | 140 | 14.4 | 632 | 18.2 | 66 | 25.9 | |

| Teleworking | 66 | 6.7 | 204 | 5.9 | 4 | 1.6 | |

| Going to work every day | 486 | 49.8 | 1796 | 51.7 | 124 | 48.8 | |

| Mixed regime | 112 | 11.5 | 360 | 10.3 | 28 | 11 | |

| Variable |

Healthy lifestyle |

Moderate healthy lifestyle |

Unhealthy lifestyle |

p-value Chi-squared test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 578 | 12.28 | 3126 | 66.45 | 1000 | 21.25 | |

| Age | |||||||

| 18-30 | 208 | 35.99 | 1118 | 35.76 | 430 | 43.00 | 0.0038 |

| 31-40 | 120 | 20.76 | 790 | 25.27 | 226 | 22.60 | |

| 41-50 | 134 | 23.18 | 698 | 22.33 | 200 | 20.00 | |

| 51-60 | 66 | 11.42 | 350 | 11.20 | 118 | 11.80 | |

| >60 | 50 | 8.65 | 170 | 5.44 | 26 | 2.60 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| F | 362 | 62.63 | 2064 | 66.03 | 710 | 71.00 | 0.0363 |

| M | 216 | 37.37 | 1062 | 33.97 | 290 | 29.00 | |

| BMI | |||||||

| Underweight | 44 | 7.61 | 154 | 4.93 | 38 | 3.80 | 0.0001 |

| Normal weight | 344 | 59.52 | 1550 | 49.58 | 394 | 39.40 | |

| Overweight | 140 | 24.22 | 922 | 29.49 | 338 | 33.80 | |

| Obese | 50 | 8.65 | 500 | 15.99 | 230 | 23.00 | |

| Residence areas | |||||||

| Urban areas | 484 | 83.74 | 2384 | 76.26 | 80 | 78.00 | 0.0193 |

| Rural areas | 94 | 16.26 | 742 | 23.74 | 220 | 22.00 | |

| Level of education | |||||||

| General/primary studies | 20 | 3.46 | 218 | 6.97 | 60 | 6.00 | 0.0167 |

| Secondary education | 124 | 21.45 | 692 | 22.14 | 274 | 27.40 | |

| Post-secondary studies | 46 | 7.96 | 268 | 8.77 | 100 | 10.00 | |

| Higher education | 212 | 36.68 | 1056 | 33.78 | 348 | 34.80 | |

| Postgraduate studies | 176 | 30.45 | 886 | 28.34 | 218 | 21.80 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single | 190 | 32.87 | 1104 | 35.32 | 394 | 39.40 | 0.1682 |

| Divorced/separated | 46 | 7.96 | 188 | 6.01 | 72 | 7.20 | |

| Married | 342 | 59.17 | 1834 | 58.67 | 534 | 53.40 | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Unemployed | 6 | 1.04 | 42 | 1.34 | 10 | 3.00 | p<0.0001 |

| Socially assisted | 2 | 0.35 | 14 | 0.45 | 10 | 1.00 | |

| Householder | 24 | 4.15 | 182 | 5.82 | 106 | 10.60 | |

| Retired | 58 | 10.03 | 178 | 5.69 | 34 | 3.40 | |

| Student | 12 | 17.65 | 542 | 17.34 | 194 | 19.40 | |

| Teleworking | 54 | 9.34 | 178 | 5.57 | 46 | 4.60 | |

| Going to work every day | 258 | 44.64 | 1648 | 52.72 | 500 | 50.00 | |

| Mixed working regime | 74 | 12.48 | 346 | 10.7 | 80 | 8.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).