1. Introduction

Specialized palliative care is associated with improved symptoms, better end-of-life quality, decreased medical costs, and higher satisfaction with family assessments [

1,

2]. Early and continuous intervention in palliative care contributes to the quality of life of patients and improved prognosis [

3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) [

4] states that palliative care “can be applied in the early stages of the disease in combination with other therapies aimed at prolonging life, such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy.” However, patients with cancer reported that their palliative care needs were unmet [

1].

Palliative care must be multidisciplinary, and guidelines have been established regarding the role of pharmacists in palliative care [

5]. Cancer is the leading cause of death in Japan, and the involvement of pharmacists in palliative care is important [

6]. A wide range of knowledge is required for the palliative care of patients with cancer. However, if a pharmacist’s knowledge is insufficient, it leads to hesitation in being proactive [

7]. For example, a report stated that a lack of training and clinical expertise is a barrier to the practice of evidence-based medicine [

8]. Therefore, complementary training should be provided to pharmacists to be proactively involved in palliative care for patients with cancer.

In a previous study, we developed an extensive and systematic educational program on palliative care for patients with cancer and found that it improves their palliative care knowledge [

9,

10]. Pharmacists must acquire knowledge and be able to provide better drug therapy to patients based on this knowledge. In other words, a pharmacist’s behavior must change after attending an educational program. Therefore, we used Transtheoretical Model 10 to evaluate how the behavior of pharmacists who participated in the palliative care educational program changed after attending the program.

2. Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Survey

A web-based questionnaire survey was conducted with the participants of an educational program held from May 2018 to March 2021 for pharmacists in nine prefectures in the southwest region of Japan: Fukuoka, Saga, Nagasaki, Kumamoto, Oita, Miyazaki, Kagoshima, Okinawa, and Yamaguchi. It assessed age, years of experience as a pharmacist, place of work, residence, and behavior (12 questions) regarding palliative care.

For each behavior related to palliative care, the behavior content and changes were investigated before attending the program (April 2018), two months after attending the program (May 2021), and eight months after attending the program (November 2021). First, from May 10 to June 21, 2021, we surveyed participants before they attended the program and two months after attending the program. The agreement forms were received before the program, and participants were asked to complete the survey while reflecting on the past. Next, from November 9 to December 14, 2021, we conducted a survey eight months after attending the program. In addition, a written questionnaire was administered to compare the participants’ behavioral changes at each time point. However, the analysis was conducted anonymously. We did not compensate the respondents for their participation. Participants agreed to participate in the survey before submitting their responses.

2.2. Behavioral Questions Regarding Palliative Care

Table 1 shows the questionnaire form regarding behavior change related to palliative care. At each time point, we asked the participants to answer the same 12 questions regarding their behavioral on a scale of 1 (“not at all”) to 10 (“good enough”).

Q1–3 addressed whether specific actions had been taken regarding pain symptoms in patients. Q4–7 addressed whether the participants could take specific actions regarding symptoms other than pain. Q8–12 addressed whether in-team medical care takes any actions toward other occupations.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Friedman’s test was used to determine whether there was a change in scores for each participant across the three time points, and Bonferroni’s adjustment [

11] was used for group comparison (post-hoc analyses). The significance level was set at p<0.05. SPSS statistics version 27.0 was used for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Collection

A total of 365 participants participated in this study. Of these, 138 (37.8%) responded to the questionnaire survey two months after attending the program, and 142 (38.9%) responded eight months after attending the program. We analyzed the responses of 96 (20.6%) participants who completed the survey both two and eight months after attending the program.

3.2. Respondents’ Characteristics

Table 2 presents the respondents’ age, years of experience as a pharmacist, place of work, and residence eight months after attending the program. The most common age group was participants in their 40s (34, 35.4 %), followed by those in their 50s (33, 34.4%). There were 0 participants in their 20s. Regarding years of experience as a pharmacist, 50 (52.1%) participants indicated “21 years or more.” Seventy-five participants (78.1%) worked at pharmacies, twenty (20.8%) at hospitals or clinics, and one (1.1%) at other hospitals. Most participants were from Fukuoka Prefecture (47, 49.0%), followed by Yamaguchi Prefecture (10, 10.4%), Saga Prefecture, Kumamoto Prefecture, and Oita Prefecture (8 each, 8.3%).

3.3. Pharmacists’ Behavioral Changes in Each Question

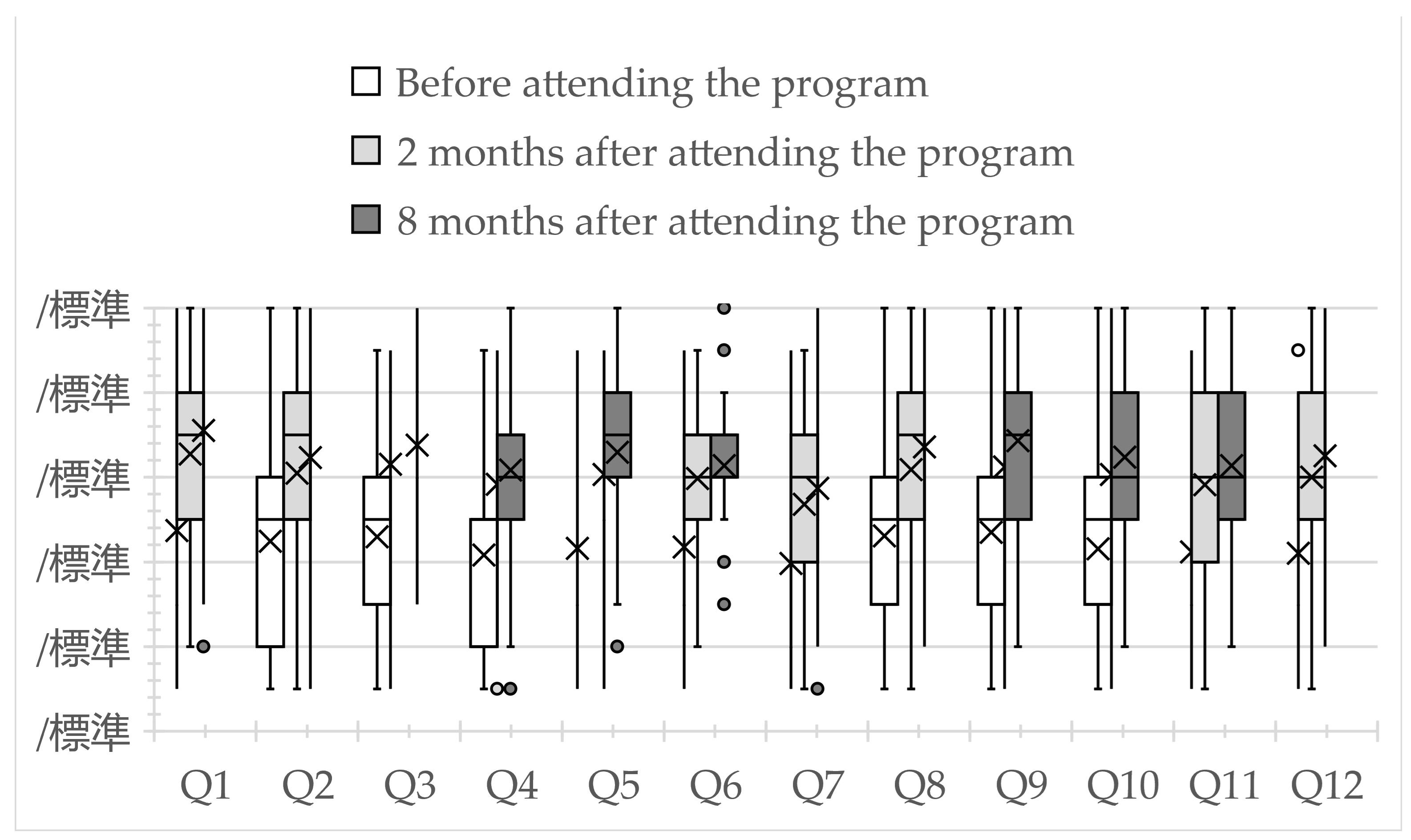

Figure 1 depicts the participants’ behavioral change scores for each question, at all three time points. Question items are shown in

Table 1. For all questions, scores were higher two and eight months after attending the program than before attending (p<0.05). In addition, no significant difference was observed between two and eight months after attending the program for all questions (p=0.504–1.000).

4. Discussion

In this study, changes in pharmacists’ behavior toward patients and healthcare professionals were observed, with scores on all 12 questions increasing at two and eight months after attending the palliative care program compared with before attending the program. This result is similar to our previous report on better behavioral changes among pharmacists in a single prefecture after attending a palliative care educational program for cancer [

12]. The program proved effective even when it was extended to nine prefectures. The results of this study are supported by previous reports of behavioral changes in pharmacists after attending an evidence-based medicine-learning program [

13]. Pharmacists who participated in a health promotion training program that included blood pressure control reported changes in their behavior and attitudes, indicating that training programs are needed to increase pharmacists’ confidence [

14]. These findings suggest that pharmacists can act proactively toward patients and healthcare professionals based on the knowledge gained from our educational program. Continuing education is required to correct the learning gap in community pharmacy [

15]. The continuation of this program appears to be important for providing better palliative care to patients.

The WHO states that palliative care is multifaceted and focuses on approaches to improving the quality of life of patients with life-threatening illnesses and their families. Palliative care is aimed at “the early identification of pain and other physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems, and the prevention and alleviation of suffering through impeccable assessment and treatment.” [

16] Guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommend that patients with cancer receive palliative care when standard treatment is initiated [

17]. Therefore, the role of pharmacists in palliative care is expected to become increasingly important. Pain is one of the most common symptoms in patients with cancer [

18]. Opioid analgesics are important drugs for pain treatment, and pharmacists have a great responsibility to alleviate patients' pain. [

19]. In addition to pain, patients with cancer unpleasant experience respiratory, psychosomatic, gastrointestinal, and urinary symptoms [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Furthermore, in palliative care, healthcare professional teams must include doctors, nurses, nutritionists, physical therapists, and medical social workers [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Namely, pharmacists need to fully understand the roles of other healthcare professionals and collaborate appropriately. Importantly, this study showed positive behavioral changes in patients’ pain and non-pain symptom relief (Q1–7). Although the level of medical resource availability differed from region to region, pharmacists in all nine prefectures deepened their understanding of multiple professionals, and were able to put them into practice (Q8–12).

This study found no change in pharmacists’ behavior scores two and eight months after completing the program, and the scores remained relatively high. In other words, the score after two months was maintained for six additional months. The repeated performance of a new behavior increases the likelihood that the behavior will become habitual and maintained [

28]. The results suggest that the knowledge gained from the educational program was used to repeatedly intervene with patients with cancer to address the various symptoms they experienced, and that the behavior was maintained. According to the transtheoretical model, when a person changes their behavior or lifestyle, they undergo five stages: “pre-contemplation,” “contemplation,” “preparation,” “action,” and “maintenance” [

29]. The maintenance phase is defined as a behavior change lasting more than six months. As applied to the present results, the pharmacists’ behavior change after attending the educational program lasted six months, implying that the pharmacists’ behavior improvement was not temporary.

This study had a limitation, including the possible bias that the pharmacists who participated in this study were highly motivated because the study was conducted retrospectively. Therefore, prospective studies are required to obtain more accurate results. This study suggests that expanding the palliative care program would result in better behavioral changes among pharmacists. In addition, we found that pharmacists’ behavioral changes were maintained. We believe that this palliative care program can serve as a stepping stone and model for nationwide expansion, as we were able to validate the program in multiple prefectures rather than in a single prefecture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M. Y. and M. U.; methodology, M. Y. and M. U.; software, M. Y., M. U., M. H., D. I., and S. A.; validation, M. Y., M. U., and M. H.; formal analysis, M. H.; investigation, D. I.; resources, H. W. and D. I.; data curation, M. Y. and M. H.; writing—original draft preparation, M. Y. and M. U.; writing—review and editing, M. Y., M. U., and M. H.; visualization, M. Y., M. U., and M. H.; supervision, S.A.; project administration, T.H.; funding acquisition, M.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a research grant of Doshisha Women's College of Liberal Arts.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethics Committee of Osaka University of Pharmaceutical Sciences on July 24, 2018 (approval no. 0060).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this study will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank all seminar participants who completed the questionnaire survey for this study. We thank Editage (

www.editage.com) for editing this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest disclosed concerning the study.

References

- Akgün, K.M. Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Patients with Malignancy. Clin Chest Med. 2017, 38, 363-376. [CrossRef]

- Schlick, C.J.R.; Bentrem, D.J. Timing of palliative care: When to call for a palliative care consult. J Surg Oncol. 2019, 120, 30-34. [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F., et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363, 733-742. [CrossRef]

- Organization, T.W.H. Availabe online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed on.

- Herndon, C.M.; Nee, D.; Atayee, R.S.; Craig, D.S.; Lehn, J.; Moore, P.S.; Nesbit, S.A.; Ray, J.B.; Scullion, B.F.; Wahler, R.G., Jr., et al. ASHP Guidelines on the Pharmacist's Role in Palliative and Hospice Care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016, 73, 1351-1367. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Kume, N. Pharmacy Practice in Japan. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2017, 70, 232-242. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, M.; Hewitt, L.Y.; Tuffin, P.H. Community pharmacists' attitudes toward palliative care: an Australian nationwide survey. J Palliat Med. 2013, 16, 1575-1581. [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, A.F.; Nakagawa, S.; Jackevicius, C.A. Cross-cultural Comparison of Pharmacy Students' Attitudes, Knowledge, Practice, and Barriers Regarding Evidence-based Medicine. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019, 83, 6710.

- Uchida, M.; Hada, M.; Yamada, M.; Inma, D.; Ariyoshi, S.; Aoki, K.; Inoue, S.; Shimazoe, T.; Mitsuiki, K.; Haraguchi, T. Impact of a systematic education model for palliative care in cancer. Pharmazie. 2019, 74, 499-504. [CrossRef]

- Uchida, M.; Yamada, M.; Hada, M.; Inma, D.; Ariyoshi, S.; Kamimura, H.; Haraguchi, T. Effectiveness of educational program on systematic and extensive palliative care in cancer patients for pharmacists. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2022, 14, 1199-1205. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple comparisons among means. Journal of the American statistical association. 1961, 56, 52-64.

- Yamada, M.; Uchida, M.; Hada, M.; Inma, D.; Ariyoshi, S.; Kamimura, H.; Haraguchi, T. Evaluation of changes in pharmacist behaviors following a systematic education program on palliative care in cancer. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2021, 13, 417-422. [CrossRef]

- Aoshima, S.; Kuwabara, H.; Yamamoto, M. Behavioral change of pharmacists by online evidence-based medicine-style education programs. J Gen Fam Med. 2017, 18, 393-397. [CrossRef]

- Shoji, M.; Onda, M.; Okada, H.; Sakane, N.; Nakayama, T. The change in pharmacists' attitude, confidence and job satisfaction following participation in a novel hypertension support service. Int J Pharm Pract. 2019, 27, 520-527. [CrossRef]

- Utsumi, M.; Hirano, S.; Fujii, Y.; Yamamoto, H. Evaluation of the pharmacy practice program in the 6-year pharmaceutical education curriculum in Japan: community pharmacy practice program. J Pharm Health Care Sci. 2015, 1, 27. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Availabe online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed on.

- Ferrell, B.R.; Temel, J.S.; Temin, S.; Alesi, E.R.; Balboni, T.A.; Basch, E.M.; Firn, J.I.; Paice, J.A.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Phillips, T., et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2017, 35, 96-112. [CrossRef]

- Mawatari, H.; Shinjo, T.; Morita, T.; Kohara, H.; Yomiya, K. Revision of Pharmacological Treatment Recommendations for Cancer Pain: Clinical Guidelines from the Japanese Society of Palliative Medicine. J Palliat Med. 2022, 25, 1095-1114. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, M.; Iihara, H.; Okayasu, S.; Yasuda, K.; Matsuura, K.; Suzui, M.; Itoh, Y. Pharmaceutical interventions facilitate premedication and prevent opioid-induced constipation and emesis in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010, 18, 1531-1538. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Goya, S.; Kohara, H.; Watanabe, H.; Mori, M.; Matsuda, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Sakashita, A.; Nishi, T.; Tanaka, K. Treatment Recommendations for Respiratory Symptoms in Cancer Patients: Clinical Guidelines from the Japanese Society for Palliative Medicine. J Palliat Med. 2016, 19, 925-935. [CrossRef]

- Bush, S.H.; Lawlor, P.G.; Ryan, K.; Centeno, C.; Lucchesi, M.; Kanji, S.; Siddiqi, N.; Morandi, A.; Davis, D.H.J.; Laurent, M., et al. Delirium in adult cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2018, 29 Suppl 4, iv143-iv165. [CrossRef]

- Hisanaga, T.; Shinjo, T.; Imai, K.; Katayama, K.; Kaneishi, K.; Honma, H.; Takagaki, N.; Osaka, I.; Matsuo, N.; Kohara, H., et al. Clinical Guidelines for Management of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Cancer Patients: The Japanese Society of Palliative Medicine Recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2019, 22, 986-997. [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, T.; Miura, T.; Hachiya, T.; Nakamura, I.; Yamato, T.; Kishida, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Irie, S.; Meguro, N.; Kawahara, T., et al. Treatment Recommendations for Urological Symptoms in Cancer Patients: Clinical Guidelines from the Japanese Society for Palliative Medicine. J Palliat Med. 2019, 22, 54-61. [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento Medina, P.J.; Díaz Prada, V.A.; Rodriguez, N.C. [The role of the family doctor in the palliative care of chronic and terminally ill patients]. Semergen. 2019, 45, 349-355.

- George, T. Role of the advanced practice nurse in palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2016, 22, 137-140. [CrossRef]

- Wittry, S.A.; Lam, N.Y.; McNalley, T. The Value of Rehabilitation Medicine for Patients Receiving Palliative Care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018, 35, 889-896. [CrossRef]

- Bekelman, D.B.; Johnson-Koenke, R.; Bowles, D.W.; Fischer, S.M. Improving Early Palliative Care with a Scalable, Stepped Peer Navigator and Social Work Intervention: A Single-Arm Clinical Trial. J Palliat Med. 2018, 21, 1011-1016. [CrossRef]

- Kwasnicka, D.; Dombrowski, S.U.; White, M.; Sniehotta, F. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: a systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol Rev. 2016, 10, 277-296. [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997, 12, 38-48. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).