1. Introduction

The popularity of using local foods is not a new concept or just a passing fad. The emphasis on local food usage has been tied to several reasons: a rebuttal against the global agri-food business conglomerate, an unending gourmand search for the tastiest selections available, a display of community pride in an area’s unique agricultural variety, or just renewed interest in healthy lifestyles. Today, Americans are being constantly reminded about the tangible, positive attributes of using fresh, preferably locally produced foods. Celebrity chefs often speak of the appreciation and awareness they have concerning the use of local foods. Chef Rick Bayless has poetically stated that, “Great food, like all art, enhances and reflects a community’s vitality, growth, and solidarity. Yet history bears witness that great cuisines spring only from healthy local agriculture [

1].” While Emeril Lagasse simply said, “I think you’ve got to keep it simple, keep it fresh. Stay away from all that processed stuff, read the labels [

2].” As more of these celebrity chefs speak about the virtues of local foods, their fans listen and go in search of their own local food treasures.

The National Restaurant Association’s (NRA) 2018 Restaurant Industry Trends Forecast cited three of their ten trends as directly related to local food sourcing, not including the idea of sustainability and vegetable-centric dishes [

3]. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the local food movement showed no sign of slowing as the 2019 Restaurant Industry Forecast predicted hyper-local foods as a top ten trend [

4]. Now that the United States has passed through the global pandemic and people are eating out again, the National Restaurant Association’s yearly trend watch has placed its focus back on consumer preferences. Overall, the top trends for 2022 pointed to plant-based sandwiches and immunity-boosting “superfoods” [

5]. Both trends are decidedly associated with local foods.

While there has been greater demand for the benefits in local food, the convenience and practicality for staying with the current supply system cannot be overlooked. The supply chain currently in place is highly efficient and accessible allowing both home and foodservice buyers to acquire products year-round, regardless of their region’s growing season. On the contrary, to secure local foods, a foodservice buyer may have to overcome several barriers such as delivery times, seasonality, or quantity availability [

6]. Even when these barriers are overcome, there may still be a pricing factor which simply do not make economic sense. For the commercial buyer, this could result in not maximizing profit margins and for the home consumer it could mean going over their household food budget. Considering the additional efforts that must be made to secure local foods, there needs to be compelling motivational reasons for a foodservice buyer to take a path peppered with increased obstacles.

The purpose of this paper is to build an expanded motivational model to identify the significant attitudinal factors identified by South Carolina foodservice buyers in their selection of local food products versus non-local products. This study will advance the research in motivational behavior models by using a modified version of the Theory of Trying to develop a more complete understanding of local food purchasing motivators.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Local Food

Being able to specify what exactly qualifies as a local food has always been debated, yet still needs to have some type of working definition. From the review of previous studies, there are numerous meanings to be considered. The spatial relationship between where a product is grown compared to where it is consumed is a strong indicator for how people define local. There also seems to be a positive connection for local foods when produced or grown within a state, especially for smaller states. Given the comparatively smaller size of South Carolina, ranked 40th in land size of all the U.S. states [

7], the boundaries should be generally agreeable for a local food designation. When drawing a 100-mile radius from the state capital of Columbia, which is centrally located, the majority of the state is also covered. The longest foreseeable distance within the state would be foods travelling between Charleston and Greenville which is 212 miles. This is somewhat longer than most studies have found when defining local through mileage but is still well within the 400-mile radius as defined by the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. When combining these two delineations, it is reasonable to define local food, for purposes of this study, as any food grown within the state of South Carolina or holds a certification from the South Carolina Department of Agriculture as “Certified South Carolina Grown” or “Certified South Carolina Product.”

2.2. Ego as a Motivator

When discussing ego, there are two categories: altruistic and self-interest. An altruistic motive would mean that the person is buying the product for the good of others. This could mean it is being purchased to help stimulate the local economy, because it is healthier for the person eating it, or the local food is just better for the environment. Regarding green purchasing, a recent study has confirmed previous studies which show either a positive correlation between attitude and intent to purchase, whereas altruism is at least a mediating effect on attitude for intent to purchase [

8]. A self-interest purchase, however, is based on making the buyer feel better about themselves, or as an attempt to look better in the eyes of their peers. Several studies have looked at these intrinsic qualities and have found many local food purchases are made for health-conscious reasons [

9,

10,

11]. There have also been several studies which have shown that food purchases are made for extrinsic reasons as well [

12,

13,

14]. As discussed previously, both reasonings are rational; for some it was a simple issue of cost and convenience which droves their purchases. For others, there may have been more time to decide, money was not a factor, or personal preferences had already been established and the consumer was inclined to buy those food products which more closely aligned with their beliefs.

Ego has been shown to be factor in the purchasing decisions of consumers in a number of models. These studies have crossed a gamut of products and services. The typical hospitality food buyer is the buyer-user. This means that the person who is buying the product is also the person who will use it and, by default, also associates the product with themselves. Rusu [

15] found that both restaurants and bars were likely to purchase local foods, but restaurants were more likely to purchase for egotistical motivations as opposed to altruistic reasons. This would seem to be in line with the perception of the egotistical chef who projects their importance to the food they serve and is making food purchases more for their own self-worth and less for the benefit to others.

By understanding if there are intangible motivators, such as ego, as opposed to purely quantitative reasons for purchasing a product, suppliers will be able to better market their products. This could also lead to newer methods of production. If it is found that food buyers are interested in local products because of the altruistic properties, growers may find newer methods of raising their foods which reduces or eliminates several chemicals or institutes Good Agricultural Practices (GAP). This may be a more important factor the buyers need as opposed to pricing, packaging, or distribution. There is also the significance of evaluating the buyer who is not necessarily the end user of the product. By end user in this case, we refer to the consumer who is buying the final, prepared meal. As mentioned before, most studies have looked at the buyer/consumer outside of the hospitality arena. Of the studies which did evaluate buyers in foodservice establishments, they were typically looking at barriers to the purchasing process and not necessarily personal motivators. Given the nature that buyers in independent properties are allowed more freedom in their decisions, it is important to understand if there are internal motivators which push the local food purchase when it is not an obvious financial gain just from a cost per unit point of view.

This idea of doing better for others has been typically assigned to the personal morals or beliefs as being an individual decision. Studies have shown that this may not be case. For example, although people may recycle and not make anyone aware of the fact, their action may be pushed because of social norms. It has been difficult to separate personal norms from social norms [

16]. Several studies have shown a strong relationship between personal norms and social norms; numerous studies have also shown a strong relationship between social norms and eco-friendly actions. At issue is the relationship between the personal norms and the eco-friendly action. For this reason, ego was selected as the personal norm variable to help determine if there is a connection between personal norms and eco-friendly actions.

Hypothesis 1: Higher levels of ego will have a positive correlation to trying to purchase local foods.

In addition, this study used a modified version of the Theory of Trying to understand what motivators best explain a commercial food service buying agent actually purchasing local foods for use in their operation. The goal is to help determine the explanatory power of modifying the Theory of Trying through the addition of ego. It is also significant that this model is already considering that perceived success or failure is not being used as a motivator as newer modifications of the model have leaned on past behaviors and frequency.

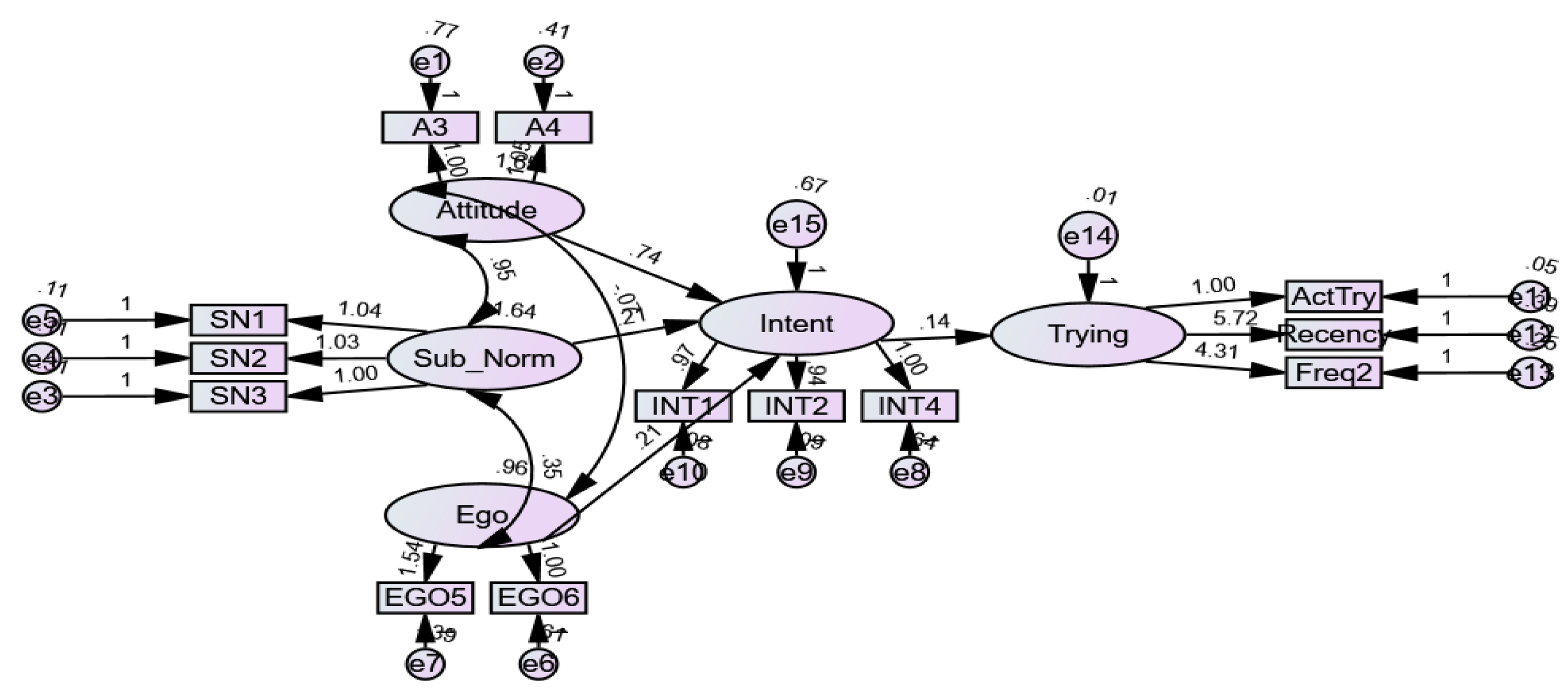

Hypothesis 2: The addition of Ego as a factor to the Theory of Trying will be a statistically predictive model for food buyers trying to purchase local foods.

There are several consumer-purchasing models which have been used in various studies. The Theory of Trying has not been as extensively tested as other classic models such as the Theory of Reasoned Action or the Theory of Planned Behavior, but it holds its place as a model framework for this proposed research. First, the concept of social norms and personal norms can be separated using ego as a new variable. Second, attitude toward purchase is an individual’s preference. This is a measure of the person’s willingness to make a certain purchase based on how they personally perceive any difficulties or personal costs they may need to endure. Third, intent can validate that the person has volition over their situation. Should the buyer have no control over the purchase of a certain good, then they would have no intention of trying to make a purchase.

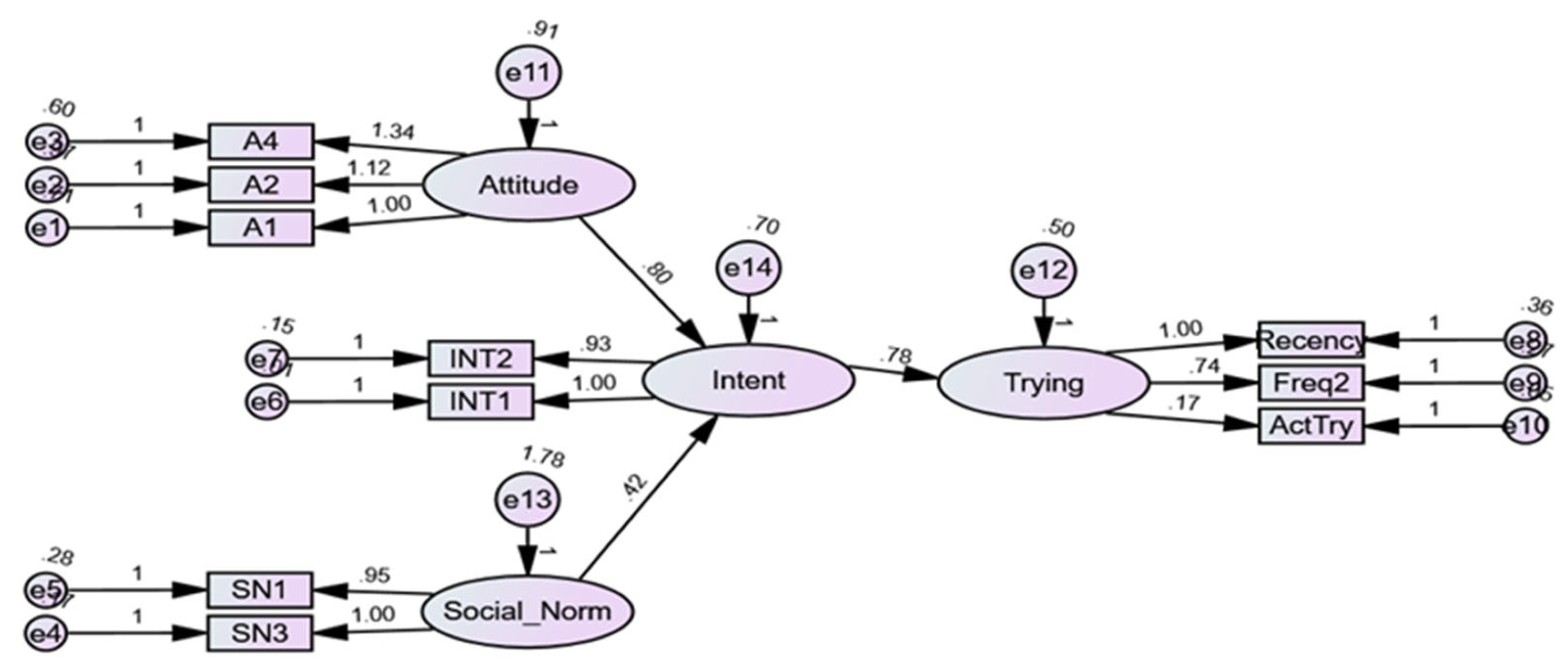

Hypothesis 3: The Theory of Trying in its current model will be a statistically predictive model for food buyers trying to purchase local foods.

In the modified model, intent is the mediating variable because no intent would nullify a person’s attitude, personal belief (ego), or any persuasion through social norms. Finally, past behaviors are included in the model. These are important factors because they can establish actual actions having been taken. Theories such as the Theory of Reasoned Action or the Theory of Planned Behavior do not consider actual actions. Normative models make the case for separating social and personal norms; however, they also raise question as to how much a social norm has become so embedded in a person that they indeed become the social norm. These studies have used personal norm to be the mediating factor for purchase intent [

17]. The Theory of Trying can more accurately gauge the effect of personal norm because actual trying can be incorporated in the model.

2.3. Conceptual Framework

The relationship between social norms, attitudes, and ego in trying to purchase local foods as mediated by intent is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Methodology

Based on the proposed hypotheses, an initial survey was developed using questions from previous research which have proven validity and reliability. All the questions which have been modified from previous studies had a Cronbach alpha of at least .70.

Before the final survey was made available, it was pilot tested by five purchasing agents who fulfilled the qualifications of a buyer in this study. These buying agents were not part of the final data collection sample. There were no recommended changes concerning the online survey.

The survey was distributed electronically through the South Carolina Restaurant and Lodging Association (SCRLA). There are 903 members of Restaurant Division of the South Carolina Restaurant and Lodging Association [

18] which receive a weekly member e-mail. These members consist of “restaurants, commercial foodservice facilities, nightclubs, bars, private clubs and others types of businesses that sell food to the public” [

19]. The survey was sent as a direct e-mail to members as well as being made available on the SCRLA website.

Of these direct emails, not all members are purchasing agents for their properties, but the relatively large membership was projected to yield a useful sample size. Members of this group were used because they are the most likely to be using South Carolina local products. South Carolina has an estimated 9,669 eating and drinking establishments which places the SCRLA as representing approximately 9% of the total state employment [

20]. That representational ratio may be even higher considering that several multi-unit owners may only have one member representing all of their properties. Although the SCRLA should be representative of the state’s restaurant population, only 237 usable surveys were returned. This represents 24.5% of the representational sample, but only 2% of the total population. The survey was available from August 1, 2019, through August 31, 2019. This was in line with the data collection period used in a study of intent to purchase by [

21].

3.1. Response Rate

Of the 903 members who received emails to participate in the survey, there were 261 responses to the survey for a response rate of 28.9%. Surveys which were incomplete were discarded resulting in a total of 237 usable surveys for a final usable rate of 90.8% and an overall usable response rate of 24.5%. Although a 60% response rate has been touted as the general “rule of thumb,” it has also been noted that lowered response rates do not necessarily mean a poor representation of findings [

22]. Realistically, a response rate between 10% and 30% is considered acceptable [

23]. The response rate falls within those parameters for the sample population, but this sample is not generalizable for the population as it only represents 2.5% of the total state population.

3.2. Data Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics v.27.0.1.0 was used to perform Exploratory Factor Aalysis (EFA) for data analysis. In a study of likelihood of buying locally produced food, exploratory factor analysis was performed, and significant factor loadings were examined to help determine purchase intention [

24]. This was also the method used in the consumer emotion study by Kim, Njite, & Hancer [

25].

5. Discussion

The results from running the initial model and the modified model using the variable of ego show that both models are useful in predicting the act of trying to purchase local foods. Both of the models fit goodness indices support the convergent and discriminate validity of the factor loadings. Although the modified model does not return a stronger overall fit than the original, it does show that ego can be a valuable predictive variable. The study supports the final hypothesis, H3: The Theory of Trying in its current model will be a predictive model for food buyers trying to purchase local foods. The study also supports the second hypothesis, H2: The addition of Ego as a factor will be a statistically predictive model for food buyers trying to purchase local foods. Additionally, the study supports many of the previous findings which tried to connect ego to purchasing motivators which validates H1: Higher levels of ego will have a positive correlation to trying to purchase local foods. The buyers in this study had many years of purchasing experience and scored high in the ego sensitivity part of the survey. This had a positive relationship to their local food purchasing trend. This confirms the same findings as Sun, Li, and Wang [

28] which found moral obligations, green self-identity, environmental concern, and social pressure have the same positive correlation to green purchase intention.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This research confirms a number of studies which have found positive correlations to environmental awareness and intent to purchase. These studies have covered a wide range of products and actions. However, this study does add a new factor to the decision-making process of food buyers. Many studies of commercial food buyers and their decisions to purchase (or not purchase) local foods have been centered around the barriers to making the actual purchase. This study reveals that long-held beliefs about some purchasing barriers may not be supported. Although buyers may state that price, invested time, or delivery schedules are indeed reasons for concern, the underlying reason for not making a purchase may have been a lack of information regarding the environmental impact their local food purchase would actually be making. Had these buyers known enough about the difference, the additional feeling of doing good may have been high enough to overcome their hesitancy. A modified Model of Trying could more accurately take this into account as a predictive model.

This study has also built on previous speculation and calls for future research to find self-motivating factors for the theory of trying. The self-motivating factor would fall into ego. As more studies are conducted which examine and refine the use of ego in the Theory of Trying, a more substantial predictive model can be built, possibly to the extent of the foundational consumer buying models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior.

5.2. Methodological Implications

Methodological implications are typically associated with qualitative studies; however, there are still study implications which can be extracted from quantitative studies as well. The Theory of Trying has, for the most part, been used in quantitative research. With the idea of adding ego, research could begin to investigate deeper associations of the participants and how their purchasing decisions are being made on a more personal level. This study seems to point in the direction of ego being a factor in the intent to try to purchase local foods, but it was studied using more of an altruistic slant. Not only can ego encompass two different reasons for a person to feel better, but there are certain nuances within those reasons. For example, an altruistic ego driver could be the person buying a local product because of the environmental effect. They could also be purchasing the product because of how another person feels when they consume local foods, and it could just as easily be a person buying local because they feel good about supporting their local community. Conversely, a more hedonistic take on ego where the person is buying local foods to feel better about themselves could have nothing to do with environment or society at all. They may feel better about purchasing locally because they know they can charge more and have a higher profit margin. They could just as easily be purchasing local foods because their peers would have more respect for them in their career. The methodology for this study was purely quantitative and it does not allow for a full picture of the driver, whether it be altruistic or hedonistic. Should ego become a more accepted factor in the Theory of Trying, it would be important to begin recognizing that more information about the participants may require the need for qualitative or mixed model methodology.

5.3. Practical Implications

This study has practical implications for the seller of local foods. Because the findings of This study reveal that the buyers are purchasing local foods because it makes them feel better about helping the environment and because it is based on their moral system. For suppliers, whether that supplier be the source or a distributor, an emphasis should be placed on the environmental impacts of their products compared to those with a larger footprint. Buyers did not seem to place as much emphasis on cost controls or even problematic issues such as additional procurement times.

Supplier sources and distributors can also use this opportunity to expand their product lines. By working with buyers, the realization of certain products (i.e., vegetable varietals or minimally processed foods) could find niche markets. Again, because of the prospect of appealing to a buyer’s altruistic ego, new product lines could be introduced to replaced what had been previously considered a closed market.

Buyers also have a takeaway from this study. Much in the same vein as any buyer should be aware of marketing claims, when buyers are looking for local foods, they need to be certain the product they are buying is indeed fulfilling the original intent. Because this study shows that buyers are purchasing local foods in part because of their feelings toward environmental protection, they need to do their due diligence to ensure the supplier or the source is upholding the same environmental points. Simply because a product is local, it does not mean the product is being grown or produced in an eco-friendly manner. Local farmers can be just as likely to use an abundance of chemicals to produce larger yields or be practicing in monocropping. Also, life cycle assessments should be used to track the environmental effects from farm to delivery. Even though a product may be raised with eco-friendly practices, processors or manufacturers may be using various additives and preservatives in the final product. Even various distribution methods may be causing the product to have a larger carbon footprint than products produced further away but with more efficient transportation methods. Depending on the egoistic driver of the buyer, other concerns such as animal husbandry or packaging could result in a local product not fully meeting the needs of the buyer.

Further studies can be conducted with modifications on the survey questions to make a stronger original model. This study also had a relatively homogenous group of participants which could skew results. Given that most participants have been in their positions for ten or more years, there may be a difference in those buyers who have less experience and be further swayed by ego than others. Analyzing the models through different demographic groupings may also find a significant difference in motivational factors as opposed to the population as a whole. Collecting data which measures restaurant size, guest demographics, buyer certifications, and buyer position in the organization (i.e., chef) could also yield significant correlations to ego.

Because ego does have predictive value in this model, wholesalers and sources for local foods can use this to their advantage. This study found the egoism drawing from environmental concerns can be used in marketing efforts to these buyers. As more studies build on the idea of ego, marketing programs can better target key points to the buyer. Upper management, at least supervisors who oversee the actual buyers, could look further into whether the purchase of local foods is improving the property in either financial positioning or guest perception.

5.4. Future Research

The data collection for this research was done before the Covid-19 pandemic. As vaccination rates began to increase and hospitalizations were decreasing, something unexpected happened: the worldwide supply chain became “sticky.” There were still labor shortages which greatly affected the transportation of material, especially in the food sector. A lack of workers in shipyards, truck drivers, and warehouse employees contributed to the slowdown of access to the world supply of food. The results of this study were measured at a time when commercial food buyers still had the luxury of essentially selecting anything they wanted at any time. When the pandemic occurred, due to the mire of supply chain consistency, buyers were forced to make purchases on a much more limited availability. It would be interesting to find the results of ego as a predictor of intent at a time when supply is short. Local foods may become, at least in the short-term as society normalizes after the pandemic, a necessity because of availability and a perceived safety protocol depending on the views of the consumer regarding imported foods.

Future research should also carry out more tests to confirm findings of the modified model. This study was done in a limited area and the acknowledgement of it not being generalizable is recognized. This was also a focused study concerning only local foods. To fully develop a new model of trying which includes ego, it would be best to examine the new framework on other purchasing types. Much of the research done using the Theory of Trying has centered around healthy options and green-friendly products. Other purchasing intent which includes those products which are not necessarily green-friendly should be used to make the framework generalizable. Ego inclusion could be of concern when buying name brand products vs generic, fair trade items, or products more inclined to be of social importance. These may include products which are viewed as abusing the labor market or products where the proceeds are used to finance unsavory actions. As has been seen with long-established models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior or the Consumer Decision Model, multiple studies were conducted over years to naturally improve and understand the interactions of factors to eventually build a stronger fitting model. This, in turn, helps to validate the findings of research using these various frameworks.

5.5. Post-Covid Implications

Because this study was done before the Covid-19 pandemic, there are numerous opportunities for applying the findings here to new food outlooks. As Rizou, Galamkis, Aldawood, and Galamakis [

29] noted, there may be additional safety concerns when purchasing food through the traditional food chain as opposed to obtaining foods directly from the farm or using local foods. The traditional food system has many more people handling the product and more opportunity for infection. This also lends itself to massive production areas which bottleneck the supply chain when they have too few employees and are unable to staff the plant. To help prevent shortages and produce a more flexile supply system a more localized system would be needed [

30]. Governments working with local and regional food suppliers was also noted as essential for helping these producers in being able to react quickly to large-scale episodes [

31].

Consumers are also having a new outlook on the products they are using at home, which should translate to new expectations at restaurants. During the pandemic, more people began cooking at home and preparing meals “from scratch.” Fountain [

32] found three different changes emerging in household: “Getting back to basics,” “Valuing local and locals,” and “ Food for well-being.” Each of these plays into the concept of using local food which may transfer to the use of more local foods and commercial buyers tapping into the idea of using foods which are perceived as being better for their guests.

5.6. Limitations of the Study

This study was conducted in South Carolina only. Thus, it would not be generalizable for the full population of food buyers in the United States. This is an initial attempt at improving the Theory of Trying model through the addition of ego and questions were taken from previous studies where ego was used as a motivator, but not for food buying managers. A more focused set of questions which better represent the traits of purchasing based on ego may need to be developed.

The participants in this study were also in their positions for a relatively long-time. A better sample of participants concerning their length of experience could also yield different results. Also, the source for the sample could be problematic in generalizing the restaurant buyer. Data could not be obtained concerning the breakdown of the types of restaurants which make up the entire state or for the types of restaurants which comprise the membership of the SCRLA.

In developing the final survey, the buying practices of the purchasing agents will be of essentially the same regional demographic which will not make it generalizable. Because the usable surveys only account for 2.5% of the total state population, it is unlikely that this sample is generalizable for the state.

Furthermore, this study does provide additional reasoning for further exploring the idea of the utility of ego in the Theory of Trying, but the lack of scope in the study cannot be considered conclusive.

Finally, demographic data was limited in determining the size of the properties that responded to the survey. The lack of information in this area impedes the ability of the research to assess the difference within groups (i.e., large volume independent users vs. small volume independent users). Although restaurants may lie within the same industry segment, their motivations may vary greatly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z. and W.K..; methodology, T.Z. and W.K.; software, W.K..; formal analysis, T.Z. and W.K.; data curation, W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Z, T.S., and W.K.; writing—review and editing, T.Z., and T.S.; visualization, T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.