1. Introduction

Thyroid nodules are common findings, and as thyroid cancer has become more prevalent globally over the past several decades, it is essential to evaluate thyroid nodules for malignancy as part of medical management [

1,

2]. While environmental and genetic aetiologies have been proposed to explain these rising patterns, a growing body of research suggests that improved healthcare availability and the use of advanced diagnostic technologies are the main causes of increases in the diagnosis of thyroid cancer [

3]. Nevertheless, other authors have discussed a genuine rise in the occurrence of thyroid cancer (TC), together with a shift in its mortality rate. However, analyses of mortality rates specific to papillary thyroid cancer in the US have shown annual rise in mortality of 1.1% overall and 2.9% specifically for papillary thyroid cancer between 1994 and 2013 [

4]. Furthermore, a rising body of evidence indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic might has increased the aggressiveness of papillary thyroid cancer. As a result, it is essential to devote more attention to the comprehensive evaluation of thyroid nodule patterns [

5,

6]. Therefore, fine needle aspiration cytology is a widely used technique for the initial evaluation of thyroid nodules, and the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology is commonly used to categorize the results of FNAC [

7,

8]. Although fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is a valuable diagnostic instrument, it presents a number of technical challenges, including sample adequacy; therefore, representative samples must be obtained using the correct technique [

9]. Nevertheless, patient cooperation, needle size, and operator expertise can all impact the sufficiency of the obtained sample. Additional obstacles in thyroid FNAC include the location and accessibility of nodules, blood interference, and cellular degeneration, which can be caused by prolonged aspiration or improper sample processing. Cellular degeneration compromises the quality of the specimen and subsequent interpretation. At last the FNAC specimens are subjectively interpreted, and cytopathologists may differ in their assessments. To tackle these technical obstacles, operator experience, procedural technique, and the implementation of supplementary measures like on-site assessment and ancillary testing are crucial for optimising the diagnostic yield and accuracy of FNAC in the context of thyroid nodules [

10].

The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (TBSRTC), third edition, made significant adjustments to improve thyroid nodule reporting and treatment. The nomenclature in this revised version was changed to clarify and standardise cytological results, minimising ambiguity and promoting uniform reporting across institutions. Also, the risk stratification approach was modified to better predict thyroid nodule malignancy based on cytology. This helped physicians make better-informed choices about patient care and follow-up [

11].

However, thyroid nodules present a significant clinical challenge due to the need to distinguish between benign and malignant nodules. Category 3 in the Bethesda System, as "Atypia of Undetermined Significance or Follicular Lesion of Undetermined Significance" (AUS/FLUS), poses particular uncertainty, as it indicates cellular abnormalities that are not definitive for malignancy. This classification requires further investigation to determine the risk of malignancy and guide appropriate clinical management. Various factors such as patient age, nodule size, and ultrasound characteristics play a crucial role in assessing the risk of malignancy in these cases [

12]. Additionally, molecular testing of FNAC material has emerged as a valuable tool in stratifying the risk of malignancy in thyroid nodules categorized as AUS/FLUS, providing deeper insights into their biological behaviour and aiding in clinical decision-making [

13,

14]. However, some experts argue that the reliance on molecular testing for risk stratification of AUS/FLUS nodules may lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment. They suggest that genetic alterations within the nodules do not always directly translate to an increased risk of malignancy, and there is a potential for unnecessary interventions based solely on molecular test results. Critics propose that a more cautious approach should be taken when interpreting molecular test findings in order to avoid unnecessary harm to patients through aggressive treatments[

15,

16]. Furthermore, the integration of clinical, radiological, and molecular data has enhanced the precision of risk stratification, allowing for a more personalized approach to the management of Bethesda category III thyroid nodules. As a result, clinicians are better equipped to recommend appropriate clinical interventions, including close monitoring, repeat fine needle aspiration, or surgical excision, based on the individualized risk assessment of AUS/FLUS nodules [

17]. Nevertheless, there are controversial data about the risk of malignancies, recurrence and clinical management of nodules in Bethesda categories III, as the reported risks of malignancy vary significantly, from 6 to 52% [

18,

19,

20].

This research examines the risk for malignancy in thyroid nodules FNAC samples categorised as Bethesda III. It is essential to comprehend the risk associated with this category in order to guide subsequent decisions and management, specifically regarding the necessity for repeated FNAC or surgical intervention.

2. Material and Methods

Particularly for patients enduring thyroid surgery, Burjeel Endocrine Surgery Centre has established a prospectively maintained surgical database. Data from 1038 consecutive patients who had bilateral or unilateral thyroidectomy by a single endocrine surgeon (I.H.) at a tertiary hospital were retrospectively analysed between January 2020 and March, 2024. Our study included 670 out of 1038 patients who underwent thyroid surgery and had preoperative FNAC of thyroid nodules with at least 30 days of follow-up. We have previously described the standard operating room (OR) procedures for thyroid surgery at our institution, including patient placement on the OR table, anaesthesia selection, equipment setup, and 9 neuromonitoring [

21].

2.1. FNAC Technique

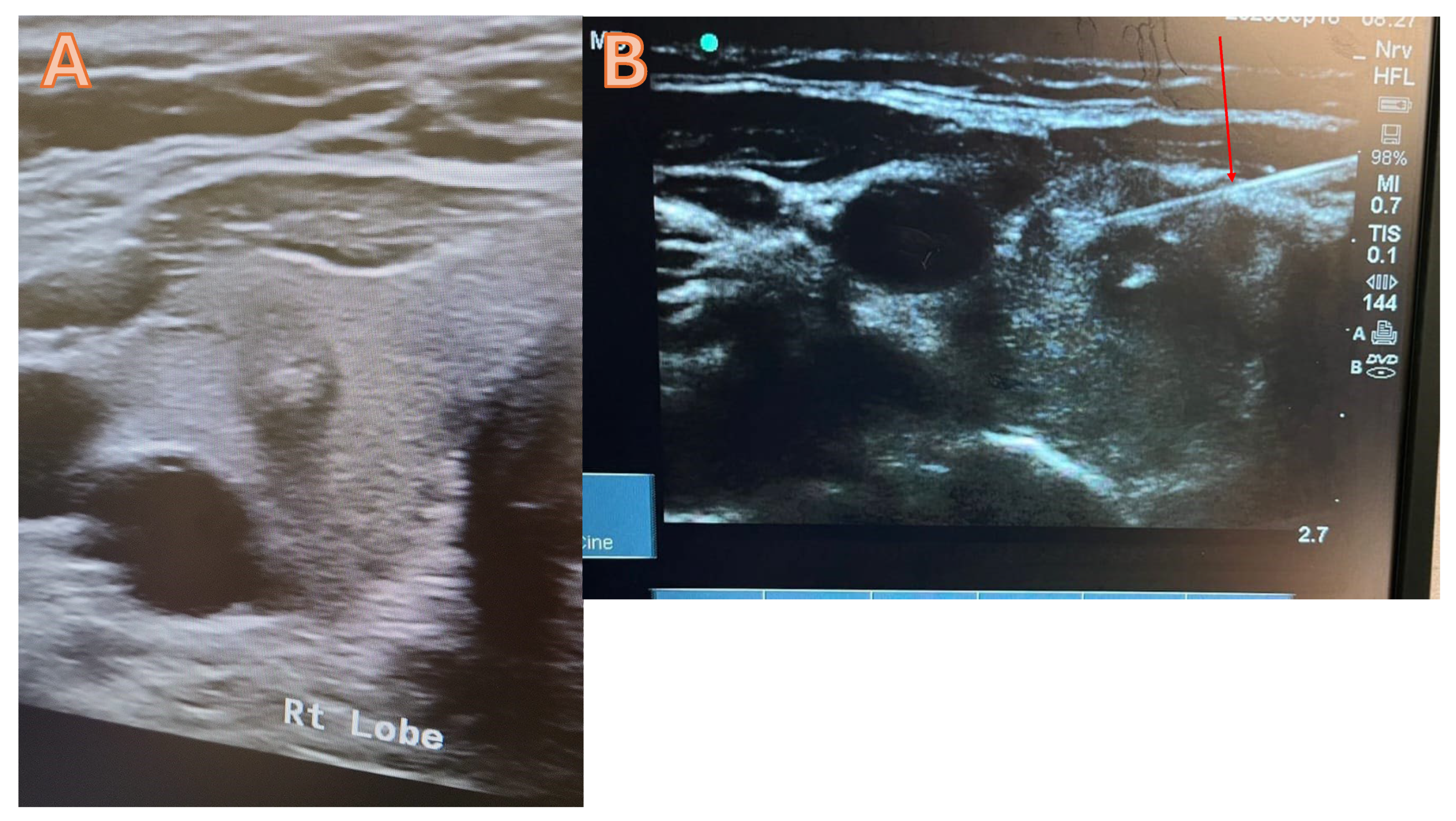

Typically, the thyroid FNAC is carried out under local anaesthesia in an outpatient setting with ultrasound guidance. In order to complete the procedure, fasting is not required. A thorough explanation of the procedure will be given to the patient by using pictures and video, and then a consent form will be obtained. Starting the procedure with the use of high-resolution ultrasound to determine the dominant nodule that requires FNAC (figure 1 a). After cleaning and sterilising the area, administer 1 mL of lidocaine (2%) to the intended site. The next step involves the trans-isthmic insertion of a 21G needle into the thyroid nodules under ultrasound guidance, requiring multiple passes to ensure proper material delivery (figure 1B). Next, withdraw the needle and equally distribute the aspirate among the slides. Before the slides have dried, immerse them in a 95% alcohol container for 30 minutes to guarantee sufficient fixation. Afterwards, the pathology lab will get the slides and proceed with their analysis. At the injection site, a plaster and an Eis pack will be applied. The patient will be monitored for thirty minutes before being discharged.

Figure 1.

A high-resolution ultrasound suggests a potentially malignant tumour in the right lobe of the thyroid, categorised as Tirad 4. B= FNAC trans isthmic, the red arrow denotes the accurate placement of the needle into the nodule.

Figure 1.

A high-resolution ultrasound suggests a potentially malignant tumour in the right lobe of the thyroid, categorised as Tirad 4. B= FNAC trans isthmic, the red arrow denotes the accurate placement of the needle into the nodule.

Staining of the thyroid FNAC sample

95% ethanol-fixed smears are stained with Papanicolaou with the Dako Cover Staining System (Dako SP30, Dako Agilent USA). Fixation prepares the sample from different sites of the body for the purpose of preserving and maintaining the existing form and structure of all constituent elements. Delay in fixation will result in air-dried artefact changes with a loss of cellular details. However, nuclear details are well visualised in Papaniolaou-stained smears at 200 or 400x magnification.

Staining of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections of surgical specimens

Specimens are accessioned and macroscopically described by anatomic pathologists. The samples were paraffin embedded according to standard techniques after 24 to 48 hours of fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Specimens sampled in cassettes are dehydrated with various grades of alcohol, cleared by xylene, and impregnated with paraffin wax with the aid of a vacuum infiltration processor (Tissue Tek VIP 6, Sakura, USA). Samples are embedded, ready for microtomy. (Tissue-Tek TEC 5, Sakura, USA). Sections of 3 to 5 μm thickness were cut from FFPE using an Accu-Cut® SRM™ 200 Rotary Microtome (Sakura, USA), and the sections were mounted on glass slides. Sections were baked before being subjected to staining. An automated haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining machine is used (VENTANA HE 600 system, Roche, USA). The HE600 deparaffinizes the sections using xylene and is rehydrated with various grades of alcohol. Primary dye Harris haematoxylin is used for nuclear staining, differentiated by acidified alcohol and blued by alkaline water. Sections are subjected to the secondary dye Eosin Y to stain the cytoplasm and extracellular matrix. The sections are again dehyrated with various graded alcohols, cleared with xylene, and coverslipped using a mounting medium. Thyroid samples were stained by immunohistochemistry using Dako Link48/PT Link (Dako Agilent,USA) if required. For further research, all stained sections were examined using a light microscope (Olympus microscope BX 46F, Japan).

2.2. Data Acquisition

The prospective surgical database combines preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative clinicopathological criteria that are particularly relevant to the progression of thyroid cancer. Standard patient characteristics, laboratory findings, and imaging investigations are also included in this resource.

Upon completing the microscopic review, the results were evaluated and double-checked by at least one additional qualified pathologist at our institution. They described the Bethesda category based on typical Cytomorphologic characteristics include architectural atypia, characterised by the presence of cellular clusters exhibiting pale and enlarged nuclei, as well as nuclear crowding and overlapping. Also histopathological assessment of surgical specimen of papillary thyroid cancer. The diagnostic criteria for this condition are as follows. Papillary architecture: Tumor cells protrude into thyroid follicles in a papillary growth pattern. The formations are called “papillae.” Nuclear features: PTC cells display nuclear expansion, clearing (ground-glass appearance), grooves, and pseudo inclusions. The “Orphan Annie eye” nuclei of PTC cells are widely mentioned. Psammoma bodies: Tumor stroma calcifications are concentric and lamellated. Classic PTC has psammoma bodies.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS version 29 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The parametric data are shown as the average value together with the measure of variability, which is the standard deviation. On the other hand, the non-parametric data are represented by the middle value (median rank) along with the range between the first and third quartiles (interquartile range). The univariate analysis included Student's t-tests and Mann-Whitney U-tests for continuous variables and Fischer's exact test for categorical data. A p-value was considered statistically significant if it was below 0.05.

3. Results

From January 2020 to March 2024, a grand total of 1038 patients who had thyroidectomy for a thyroid condition were identified. A total of 670 patients had preoperative FNAC which were included in the final analysis. In this study, the ratio of females to males was 137:533 in the entire group, and the median age was 43 years (SD 11.8). However, 47.5% of surgical histologies were malignant. Younger patients had a more malignant surgical histology than benign ones. Patients diagnosed with benign disease had an average age of 44.7 years, whereas those diagnosed with malignancy had an average age of 41.1 years (Anova test, p = 0.0001). The histopathology features showed a trend towards larger tumour foci in male patients (average 13.4 mm) when compared to females (average 11.7 mm). However, while female patients has significant more less invasive tumors (chi-square test, p = 0.0001) further poor prognostic factors, including bilateral multifocality did not differ between the genders (chi-square test, p = 0.052).

Additional characteristics related to the comparison between the two genders are shown in

Table 1 and 2.

3.1. Comparison with other Bethesda Categories

The prevalence of cancer in Bethesda III nodules was comparable to that of Bethesda IV, with rates of 33.5% and 33.8%, respectively. However, the incidence of cancer in Bethesda III nodules was lower than that in Bethesda V nodules, which had a malignancy rate of 98.3%. It is worth noting that the risk of malignancy in Bethesda VI nodules is precisely the same as that in Bethesda V nodules. However, the risk of malignancy for Bethesda I was 17.6%, which is comparable to the risk of malignancy in the Bethesda II group, which is 18.3% (

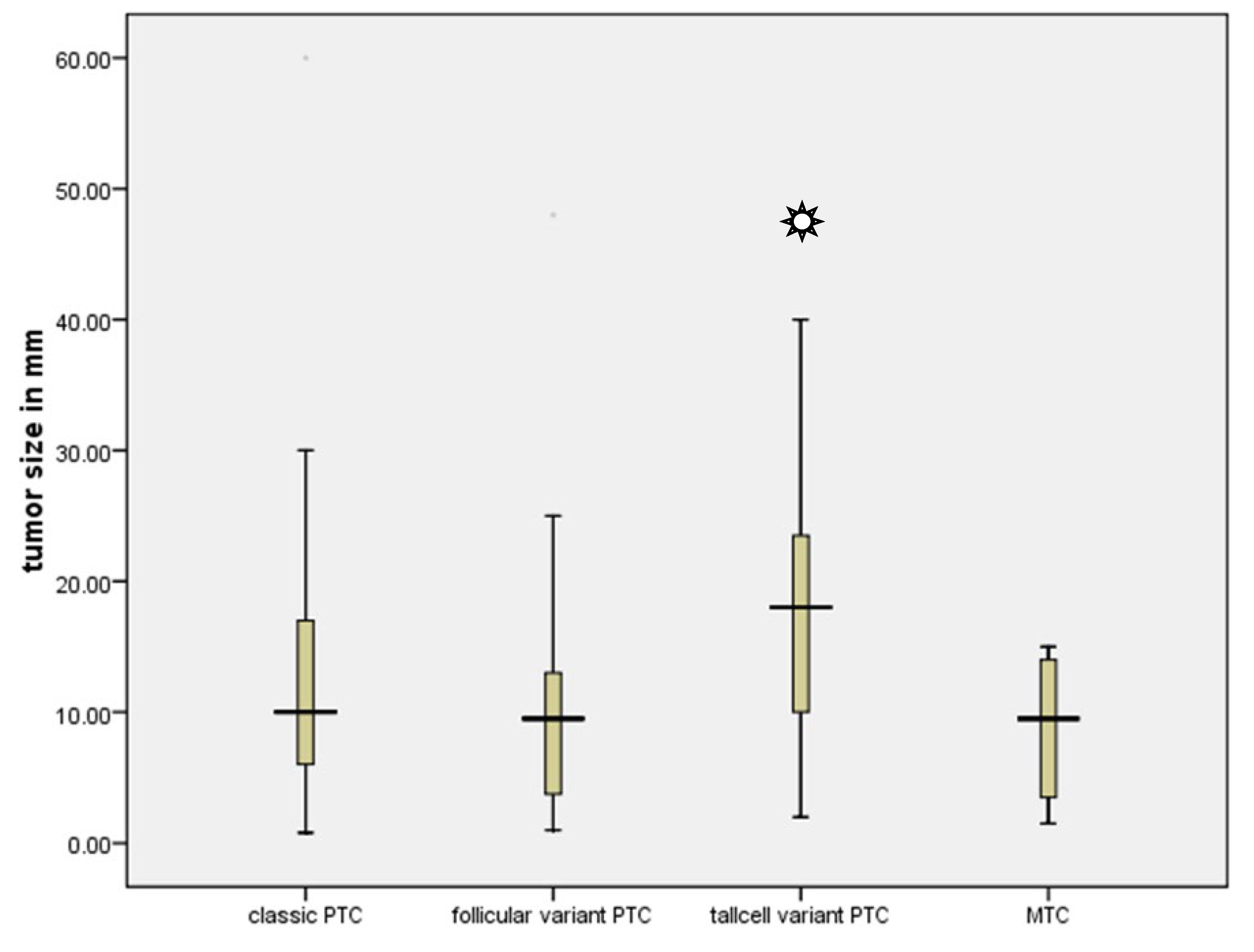

Table 3). In addition, the complete group consisted of 201 instances of classic papillary thyroid cancer, 52 cases of follicular variation of papillary thyroid cancer, 19 cases of tall cell variant, and 12 cases of medullary thyroid cancer. Nevertheless, the tall cell variant exhibited a significantly larger mean diameter of 17.5 mm in comparison to all other tumours (Kruskal-Wallis Test, p=0.49) (

Figure 2).

3.2. The Impact of Hurthle Cells in FNAC Sample

Hurthle cells were prominently present in the fine needle aspiration samples from 122 out of 670 patients, representing 18.2% of the total. The final surgical histology revealed 44 malignant cases (36%) and 78 benign cases (64%) (Fisher Exact Test, sample size = 0.002). A Hurthle cell predominate nodule was discovered in 53 out of 170 patients (31.2%) in the Bethesda category III subgroup. Out of these 53 instances only 18 (34%) were identified to have a malignant nodule, whereas 35 cases (64%) were benign in the surgical histology (chi square test, p = 0.0001). On the other hand, out of the 117 patients who had a hurthle cell-negative FNAC sample, 39 instances (33.3%) were found to be malignant, whereas 78 cases (66.7%) were found to be benign in the final surgical histopathology (chi square test, p = 0.0001).

4. Discussion

Thyroid carcinoma is the most common kind of cancer affecting the endocrine system, and its occurrence is on the rise globally. Thyroid cancer is three times more common in women than in men in the United Arab Emirates. The evaluation of a thyroid gland lesion requires a thorough examination using clinical, radiographic, cytological, and histological techniques. Early detection of thyroid tumours is crucial, as new information suggests that more aggressive forms have emerged in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic [

4,

5]. Several classification strategies have been developed to reduce discrepancies among observers while reporting thyroid cytology. The Bethesda Reporting System of Thyroid Cytopathology was established in 2009 and has gained widespread acceptance in the United States of America, the Arabian Gulf, and several other regions of the globe. It experienced various adjustments throughout the years [

22,

23].

Thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda III, especially Atypia of Undetermined Significance or Follicular Lesion of Undetermined Significance (AUS/FLUS), provide unique challenge in medical management. The precise risk of malignancy for this category remains undetermined due to the presence of several nodules categorised as AUS/FLUS that have not undergone verification by surgical pathology. In 2009, the first edition of BRTCS projected that the probability of malignancy for Bethesda Category III was between 5-15% [

22]. However, the third edition of TBSRTC released in 2023 revealed a higher risk of malignancy at 22% [

23]. Other researcher of recent literature have even reported a higher risk of malignancy for Bethesda II and Bethesda category III. For instance Inabnet et al reported a large cohort of 21764 patients who underwent thyroidectomy in 314 institutions across 22 countries. The study compared the findings of FNAC with surgical specimens. In their analysis Bethesda category II was associated with an approximately 13% risk of malignancy, while Bethesda category III was associated with a 32% risk. A subsequent analysis of the same cohort revealed that male Bethesda III patients aged 36–40 had a 56% increas0ed risk of malignancy[

20].

In our study, the Bethesda II category of patients constituted 26.9%, followed by Bethesda III, constituting 25.4%. Our investigation showed that both Bethesda categories II and III had a malignancy rate that exceeded the limit specified by the Bethesda System first and third edition. The study's findings indicate that the higher malignancy incidence is closely linked to the presence of referral and selection bias since the research was conducted at a tertiary-care centre, where patients were referred due to a higher likelihood of malignancy.

The uncertainty surrounding the potential for malignancy in these nodules underscores the importance of accurate risk assessment and appropriate management strategies. In this context, the present study aimed to investigate the risk of malignancy of Bethesda category III in a large patient cohort operated at a high volume endocrine surgery center in the United Arab Emirate. Based on the findings of current study, the overall rate of malignancy has been estimated to be 47.5%. Additionally, for nodules classified as Bethesda category III, the malignancy rates was 33.5%. The prevalence of our data is similar to that of research conducted by thakar et al [

24], which suggested a range of 26.6%–37.8% for Bethesda category III. However, Alhassan et al also from the gulf region reported in only 137 patients who had underwent thyroid surgery, and FNAC a malignancy rate of 55.6% in Bethesda III category [

25]. Ali Khalil et al reported in previous study from UAE on 584 patients a malignancy rate of 20% for indetermined nodule [

26]. The discrepancy in the malignancy rate of an indeterminate nodule between Ali Khalil's published study and the current study may be attributed to the utilisation of distinct classification systems. Ali Khalil's study employed the UK Royal College of Pathologists Thy Terminology, whereas the current study adopted the Bethesda classification system. The limited number of their surgical cases may also account for the difference. Specifically, only 30 patients in their study received surgical resection for an indeterminate nodule, while our analysis included 170 individuals who underwent surgery for the same reason. A further study conducted in a related geographical area by -Fatima et al yielded comparable results for Bethesda category III. Out of the 104 resection specimens with preoperative FNAC der category Bethesda III in their study, 72 (69.2%) were determined to be benign, whereas 32 instances (30.7%) were diagnosed as malignant [

27]. However, some European research on the other hand revealed malignancy risk of 15% for Bethesda category III when compared to surgical histopatholgy which is in line with the original TBSRTC- data [

28].

In contrast to previous research findings, our study did not demonstrate a gender bias towards malignancy in Bethesda Category III [

29]. This is because malignant nodules accounted for one-third of the total group in both males and females. However, malignant nodules in the Bethesda category III were more prevalent in younger individuals with a mean age of 41 years, while benign nodules were detected at an average age of 44 years. This finding might confirm the finding published by Walters et al., who observed in a cohort of comparable size to ours that the likelihood of malignancy for Bethesda III is 38.3%, with younger age being the only predictor that showed statistical significance in terms of increased risk of malignancy[

30].

Another noteworthy finding from our analysis is the impact of a FNAC sample with a significant amount of hurthle cells on estimating the risk of malignancy in the suspicious nodule. The reason for this is that FNAC samples with prominent hurthle cell features remain challenging for review. In our investigation, 18.2% of the samples had a hurthle cell predominance rate, meaning that over 50% of the cells in the FNAC sample were hurthle cells. These proportions are not markedly different from those reported by other investigators [

31,

32] . When compared to surgical pathology, we found only one third of the predominant hurthle cell nodules, as shown in the FNAC sample to be malignant. This is in line with recent reports by Ren et al who found malignancy risk is not impacted by hurthle cells predominant FNAC. [

33] . This is particularly important in order to avoid over-interpretation of hurthle cell lesions and facilitate appropriate patient management.

Lastly, our analysis revealed that the malignancy rate for nodules categorised as Bethesda category II was 18.3%, a much higher rate than that which was published in the third edition of Bethesda, which maintained the 4% risk of malignancy for Bethesda category II nodules[

23]. However, a recent study conducted by Mulita et al. observed that the malignancy risk for the Bethesda II category is even lower at 1.58% [

34]. In contrast, a study by Muri et al. involving 5030 patients showed a malignancy risk of 9% [

35], which is similar to the previously mentioned study from the European and American registry that reported a malignancy risk of 12.7% for the Bethesda II category [

20]. The underreporting of clinical variables that influence the decision to proceed with surgical intervention despite a benign cytological diagnosis may account for the discrepancy in the risk of malignancy associated with Category II specimens between our study and the others. Thyroid dysfunction, nodule size, local compression, ultrasound features, family history, patient preference, and radiation exposure history are a few more risk factors that need to be considered when evaluating the likelihood of malignancy and choosing a surgical procedure in 0this category.

There are several limitations inherent in our study. The main constraint is the lack of available data pertaining to patients who underwent molecular testing using the FNAC sample. The main hindrance to acquiring this vital measure was the absence of insurance coverage and the unavailability of the technology in the UAE, necessitating the dispatch of samples, hence further augmenting the expense. Furthermore, the Bethesda III group's even with 170 patients remains a small cohort and limited the ability to draw more definitive conclusions. We attribute the limited relevance of our results to the retrospective nature of our investigation, conducted at a single site. To assess our results, it is necessary to conduct prospective studies, preferably with larger sample sizes from diverse geographies and a specific emphasis on genetic and biological research.

5. Conclusions

Our study results indicate that high-volume centres may have a greater incidence of malignant thyroid nodules in the final surgical pathology since our endocrine surgery center detected malignancy in 47.5% of the thyroidectomy patients. Furthermore, Bethesda categories I-III are associated with a heightened risk of malignancy compared to third edition of TBSRTC, particularly among younger patients. Furthermore, our data indicate a notable gender disparity in malignancy risk within Bethesda category II, with female patients exhibiting a higher susceptibility compared to their male counterparts. This emphasises the necessity of individualised risk assessment and patient counselling, taking into account gender-specific factors when determining the optimal course of action.

In summary, our study underscores the evolving landscape of thyroid nodule risk stratification in the Arabian Gulf region and highlights the imperative for nuanced, patient-centred approaches to optimise diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying factors contributing to these observed trends and to refine risk assessment strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of the population under study.

Author Contributions

Data curation, M.A.; investigation, I.H.; writing, reviewing and editing, N.A, L.H and H.A.; promotion and inspiration, M.Al. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Burjeel Hospital in Abu Dhabi (BH/REC/Institutional Review Board/033/22). All patients who took part in the study signed a written informed consent form when they were admitted.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the results of this study can be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Burjeel Holdings founder and chairman, Dr. Shamsheer Vayalil, who is both the impetus behind our mission to improve the level of service that we provide to the community as well as our primary source of inspiration and the motivation for carrying on our work. Additionally, we would like to thank John Sunil, Waleed Tawfik, the endocrine surgery team and Deepan Gd, who make up the senior management team at Burjeel Hospital, for guiding us with their passionate support, insightful comments, and constructive criticism about this research. Finally, my son Wiam Hassan is the driving force behind my desire to better serve my community and my source of inspiration and motivation to keep going. Thanks a lot for everything, Wiam.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Horn-Ross, P.L.; Lichtensztajn, D.Y.; Clarke, C.A.; Dosiou, C.; Oakley-Girvan, I.; Reynolds, P.; Gomez, S.L.; Nelson, D.O. Continued rapid increase in thyroid cancer incidence in california: Trends by patient, tumor, and neighborhood characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 1067–1079.

- Pellegriti, G.; Frasca, F.; Regalbuto, C.; Squatrito, S.; Vigneri, R. Worldwide increasing incidence of thyroid 2cancer: Update on epidemiology and risk factors. J. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013, 2013, 965212.

- Hu, J.; Yuan, I.J.; Mirshahidi, S.; Simental, A.; Lee, S.C.; Yuan, X. Thyroid Carcinoma: Phenotypic Features, Underlying Biology and Potential Relevance for Targeting Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1950. PMID: 33669363. [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Devesa, S.S.; Sosa, J.A.; Check, D.; Kitahara, C.M. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974–2013. JAMA 2017, 317, 1338–1348.

- Hassan I, Hassan L, Bacha F, Al Salameh M, Gatee O, Hassan W. Papillary Thyroid Cancer Trends in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Is There a Shift toward a More Aggressive Entity? Diseases. 2024 Mar 20;12(3):62. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhan, L.; Guo, L.; Yu, X.; Li, L.; Feng, H.; Yang, D.; Xu, Z.; Tu, Y.; Chen, C.; et al. More aggressive cancer behaviour in thyroid cancer patients in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era: A retrospective study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 7197–7206.

- Seagrove-Guffey MA, Hatic H, Peng H, Bates KC, Odugbesan AO. Malignancy rate of atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance in thyroid nodules undergoing FNA in a suburban endocrinology practice: A retrospective cohort analysis. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018 Oct;126(10):881-888. [CrossRef]

- Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The 2017 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid. 2017 Nov;27(11):1341-1346. [CrossRef]

- Chong Y, Park G, Cha HJ, Kim HJ, Kang CS, Abdul-Ghafar J, Lee SS. A stepwise approach to fine needle aspiration cytology of lymph nodes. J Pathol Transl Med. 2023 Jul;57(4):196-207. [CrossRef]

- Sujatha R, Gayathri J, Jayaprakash H.T. Thyroid FNAC: Practice and Pitfalls. Indian Journal of Pathology and Oncology. 2394-6784. Online ISSN : 2394-6792. 2017 (2) 203-206. [CrossRef]

- Ali SZ, Baloch ZW, Cochand-Priollet B, Schmitt FC, Vielh P, VanderLaan PA. The 2023 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid. 2023 Sep;33(9):1039-1044. [CrossRef]

- Prete A, Borges de Souza P, Censi S, Muzza M, Nucci N, Sponziello M. Update on Fundamental Mechanisms of Thyroid Cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020 Mar 13;11:102. [CrossRef]

- Suh YJ, Choi YJ. Strategy to reduce unnecessary surgeries in thyroid nodules with cytology of Bethesda category III (AUS/FLUS): a retrospective analysis of 667 patients diagnosed by surgery. Endocrine. 2020 Sep;69(3):578-586. [CrossRef]

- 1: Floridi C, Cellina M, Buccimazza G, Arrichiello A, Sacrini A, Arrigoni F, Pompili G, Barile A, Carrafiello G. Ultrasound imaging classifications of thyroid nodules for malignancy risk stratification and clinical management: state of the art. Gland Surg. 2019 Sep;8(Suppl 3):S233-S244. [CrossRef]

- Nishino M, Mateo R, Kilim H, Feldman A, Elliott A, Shen C, Hasselgren PO, Wang H, Hartzband P, Hennessey JV. Repeat Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology Refines the Selection of Thyroid Nodules for Afirma Gene Expression Classifier Testing. Thyroid. 2021 Aug;31(8):1253-1263. [CrossRef]

- Ling J, Li W, Lalwani N. Atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesions of undetermined significance: What radiologists need to know. Neuroradiol J. 2021 Apr;34(2):70-79. [CrossRef]

- Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133. [CrossRef]

- Yaprak Bayrak B, Eruyar AT. Malignancy rates for Bethesda III and IV thyroid nodules: a retrospective study of the correlation between fine-needle aspiration cytology and histopathology. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020 Apr 15;20(1):48. [CrossRef]

- Kasap ZA, Kurt B, Özsağır E, Ercin ME, Güner A. Diagnostic models for predicting malignancy in thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda Category III in an endemic region. Diagn Cytopathol. 2024 Apr;52(4):200-210. [CrossRef]

- Inabnet WB 3rd, Palazzo F, Sosa JA, Kriger J, Aspinall S, Barczynski M, Doherty G, Iacobone M, Nordenstrom E, Scott-Coombes D, Wallin G, Williams L, Bray R, Bergenfelz A. Correlating the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology with Histology and Extent of Surgery: A Review of 21,746 Patients from Four Endocrine Surgery Registries Across Two Continents. World J Surg. 2020 Feb;44(2):426-435. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, I.; Hassan, L.; Gamal, I.; Ibrahim, M.; Omer, A.R. Abu Dhabi Neural mapping (ADNM) during minimally invasive thyroidectomy enables the early identification of non-recurrent laryngeal nerve and prevents voice dysfunction. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 5677. [CrossRef]

- Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid. 2009 Nov;19(11):1159-65. [CrossRef]

- Ali SZ, Baloch ZW, Cochand-Priollet B, Schmitt FC, Vielh P, Vander Laan PA. The 2023 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid. 2023 Sep;33(9):1039-1044. [CrossRef]

- Thakur A, Sarin H, Kaur D, Sarin D. Risk of malignancy in Thyroid "Atypia of undetermined significance/Follicular lesion of undetermined significance" and 0its subcategories - A 5-year experience. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2019 Oct-Dec;62(4):544-548. [CrossRef]

- Alhassan R, Al Busaidi N, Al Rawahi AH, Al Musalhi H, Al Muqbali A, Shanmugam P, Ramadhan FA. Features and diagnostic accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology of thyroid nodules: retrospective study from Oman. Ann Saudi Med. 2022 Jul-Aug;42(4):246-251. [CrossRef]

- Khalil AB, Dina R, Meeran K, Bakir AM, Naqvi S, Al Tikritti A, Lessan N, Barakat MT. Indeterminate Thyroid Nodules: A Pragmatic Approach. Eur Thyroid J. 2018 Jan;7(1):39-43. Epub 2017 Nov 21. PMID: 29594053; PMCID: PMC5836223. [CrossRef]

- Fatima S, Qureshi R, Imran S, Idrees R, Ahmad Z, Kayani N, Ahmed A. Thyroid cytology in Pakistan: An institutional audit of the atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance category. Cytopathology. 2021 Mar;32(2):205-210. [CrossRef]

- Huhtamella R, Kholová I. Thyroid Bethesda Category AUS/FLUS in Our Microscopes: Three-Year-Experience and Cyto-Histological Correlation. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Oct 28;11(11):1670. PMID: 31661800; PMCID: PMC6895794. [CrossRef]

- Cho JS, Yoon JH, Park MH, Shin SH, Jegal YJ, Lee JS, Kim HK. Age and prognosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma: retrospective stratification into three groups. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012 Nov;83(5):259-66. Epub 2012 Oct 29. PMID: 23166884; PMCID: PMC3491227. [CrossRef]

- Walters BK, Garrett SL, Aden JK, Williams GM, Butler-Garcia SL, Newberry TR, Mckinlay AJ. Diagnostic Lobectomy for Bethesda III Thyroid Nodules: Pathological Outcomes and Risk Factors for Malignancy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2021 Sep;130(9):1064-1068. Epub 2021 Feb 10. PMID: 33567896. [CrossRef]

- Yuan L, Nasr C, Bena JF, Elsheikh TM. Hürthle cell-predominant thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology: /A four risk-factor model highly accurate in excluding malignancy and predicting neoplasm. Diagn Cytopathol. 2022 Sep;50(9):424-435. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal S, Bychkov A, Jung CK, Hirokawa M, Lai CR, Hong S, Kwon HJ, Rangdaeng S, Liu Z, Su P, Kakudo K, Jain D. The prevalence and surgical outcomes of Hürthle cell lesions in FNAs of the thyroid: A multi-institutional study in 6 Asian countries. Cancer Cytopathol. 2019 Mar;127(3):181-191. [CrossRef]

- Ren Y, Kyriazidis N, Faquin WC, Soylu S, Kamani D, Saade R, Torchia N, Lubitz C, Davies L, Stathatos N, Stephen AE, Randolph GW. The Presence of Hürthle CellsDoes Not Increase the Risk of Malignancy in Most Bethesda Categories in Thyroid Fine-Needle Aspirates. Thyroid. 2020 Mar;30(3):425-431. [CrossRef]

- Mulita F, Iliopoulos F, Tsilivigkos C, Tchabashvili L, Liolis E, Kaplanis C, Perdikaris I, Maroulis I. Cancer rate of Bethesda category II thyroid nodules. Med Glas (Zenica). 2022 Feb 1;19(1). Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34734516. [CrossRef]

- Muri R, Trippel M, Borner U, Weidner S, Trepp R. The Impact of Rapid On-Site Evaluation on the Quality and Diagnostic Value of Thyroid Nodule Fine-Needle Aspirations. Thyroid. 2022 Jun;32(6):667-674. Epub 2022 May 20. PMID: 35236111. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).