1. Introduction

Flooding is a catastrophic natural disaster progressively growing in frequency and severity, primarily attributed to climate change-induced phenomena such as heightened rainfall intensity. Generally, there are three prevalent flood types: fluvial or river floods, pluvial or flash floods, and coastal floods. A flash flood is a sudden and severe local inundation often resulting from high-intensity rainfall (e.g., tropical cyclones, slow-moving tropical depressions, or thunderstorms) within a short period (usually less than six hours) and/or may also be caused by sudden discharge of impounded water (e.g., dam or levee failures, ice jam release, or a glacier lake outburst) [

1,

2]. Flash floods can affect a range of locations, including river plains, valleys, and areas with steep terrain, elevated surface runoff rates, constrained stream channels, and persistent heavy convective rainfall [

1]. They often necessitate prompt action to mitigate their severe impact, typically relying on expeditious decision-making and emergency response. Flash floods make up about 85% of all floods, resulting in more than 5,000 deaths annually and causing severe social, economic, and environmental impacts [

3]. The repercussions of flood disasters are more devastating in developing countries such as Fiji [

4], where this study is focused. Therefore, developing a real-time flood risk monitoring tool remains an ongoing research motivation to enable an assessment of flood occurrences for early warning systems in Fiji.

Fiji experiences regular flooding events arising from orographic rainfall due to the topography of its larger islands, including Viti Levu and Vanua Levu, which have a maximum elevation of 1300 meters above sea level, along with the impact of prevailing southeast trade winds [

5]. For Fiji, about 90% of its population resides in coastal areas susceptible to floods [

6]. Between 1970 and 2016, Fiji faced 44 major flood events, impacting approximately 563,310 people and resulting in 103 fatalities [

7]. The most catastrophic floods occurred in 2004, 2009, 2012 (including the January and March flood events), and 2014. The 2009 and 2012 events, considered among the worst in the nation’s history, resulted in over 200 million FJD in damages and losses, causing 15 fatalities and directly affecting more than 160,000 people [

7]. For Fiji, the estimated average annual flood losses exceed 400 million FJD, equivalent to 4.2 percent of Fiji’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [

7]. These are substantial losses for a small island nation with a population of less than a million and a GDP of less than 5 billion USD [

8]. Under the assumption that climate change conditions will significantly increase rainfall, flood-related asset losses could exceed 5 percent of the GDP by 2050 [

7]. As a result, it is imperative to develop reliable methods for accurately monitoring flood risk on near real-time (e.g., hourly) timescales to mitigate the severe impacts of flooding.

In many developing nations where flood monitoring resources, hydro-meteorological datasets and risk monitoring facilities are underdeveloped, applying a mathematically derived flood index utilising only the rainfall data provides a key incentive to assess an impending flood risk situation. Some of the key mathematical indices used previously in flood risk monitoring include the Standardised Precipitation Index (

) [

9], the Available Water Resources Index (

) [

10], the Weighted Average of Precipitation (

) [

11], the Standardised

(

) [

12], the Flood Index (

) [

13] and the Standardised Antecedent Precipitation Index (

) [

14]. The flood indices, such as

,

,

, and

, are robust as they are designed to account for changes in antecedent or immediate past rainfall by employing a suitable time-dependent reduction function that accounts for the depletion of water resources through various hydrological processes. For example, the daily flood index,

applied in Australia [

13], Iran [

15], Bangladesh [

16] and Fiji [

4] has shown good performance in monitoring flood events albeit over daily scales. Despite its benefits, one primary weakness of

and other indices, such as

, lies in their utilisation of daily, monthly, or annual accumulated rainfall data, which represent much longer timescales than what is required in a flash flood monitoring system. Consequently, these indices fail to adequately represent the flood risk caused by bursts of high-intensity rainfall and rapid responses leading to flash flood events.

The present study draws relevance from a pilot study conducted by Deo et al. [

17] that has proposed a 24-hourly water resource index (

) based on the concept similar to the

, which was applied in two study locations, Australia and South Korea, to monitor the flash flood risk in sustained extreme rainfall periods. The

monitors flood risk by considering the contribution of accumulated rainfall in the past 24 hours, whereby the rainfall contribution from the preceding hours is subjected to the time-dependent reduction function that accounts for the depletion of water resources through various hydrological processes such as evaporation, percolation, seepage, runoff, and drainage [

17]. However, unlike

and

, which are normalised values derived from the Antecedent Precipitation Index (

) and the

, respectively, the identification of flood events and the computation of their characteristics are not achievable with the current form of

, primarily because this index is unnormalised and does not enable objective assessment of flood risk.

To comprehensively understand flood risks, it is essential to calculate the flood characteristics, including the volume (

V), peak (

Q) and duration (

D) that concurrently results in major collateral damage [

14]. As the flood characteristics such as the

D,

V and

Q are mostly interrelated, we envisage that these characteristics should be jointly considered in a multivariate analysis model to estimate the actual probability of a flood occurrence [

14,

18]. Importantly, any model representing the joint distribution of

D,

V,

Q, and other crucial flood characteristics, such as the onset and withdrawal of a flood event, can provide significant insights into the relative severity of any flood event. After the initial study of Sklar [

19], copula-based models became attractive in modelling interrelated variables, albeit using a multivariate approach. As such, copulas can jointly model the distribution of flood characteristics such as the

D,

V and

Q, regardless of their marginal distributions or whether their dependence structure is linear or non-linear [

14]. Vine copulas have recently shown superior capabilities in modelling flood characteristics compared to traditional Archimedean and elliptical copulas [

14,

20,

21,

22]. Therefore, this research follows a recent study by Nguyen-Huy et al. [

14], which used the vine copulas to model the joint distribution of extreme flood characteristics derived using the

in Myanmar. Their study has provided interesting insights into the probabilistic flood risk analysis. Besides the study of Nguyen-Huy et al. [

14] in Myanmar, no prior research has applied vine copulas to analyse the probabilistic flood risk in Fiji despite flash floods being a catastrophic phenomenon in this small island nation.

The scientific contributions of this paper, with significant implications for flood risk monitoring and assessment, are threefold. Firstly, the paper advances the concept of the 24-hour water resources index pioneered by Deo et al. [

17] and formulates a novel hourly flood index (

) (a normalised metric) by normalising the 24-hourly water resources index in such a way that enables the objective assessment of flood risk at an hourly scale. Secondly, the present study adopts the

, which is computed using real-time hourly rainfall data from 2014 to 2018 obtained from the Fiji Meteorological Services (FMS), to evaluate its practical utility in identifying flood situations and computing their associated flood characteristics (i.e.,

D,

V, and

Q) for seven different study sites in Fiji. Thirdly, the present study develops the vine copula approach for the first time to model the joint distribution of

D,

V and

Q derived from the

for specific cases of Fiji’s flood events to extract their joint exceedance probabilities for probabilistic flood risk assessment. The methodologies presented in this study aim to enhance and contribute to the existing monitoring and early warning systems for flash floods in Fiji and their potential application to other flood-prone regions around the globe.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides information on the study area, the dataset used, and data pre-processing steps. It also encompasses the mathematical methodology for computing the hourly flood index and the flood characteristics. Additionally, it provides details on Vine copula models and equations used for computing the joint exceedance probability of flood characteristics.

Section 3 provides the results and discussion.

Section 4 highlights the key findings, the study’s limitations, and insights for future research.

4. Conclusions, Limitations of the Study and Future Research Directions

This study has made novel contributions to flood risk monitoring and assessment by developing a mathematically convenient hourly flood index, and testing its practical use in identifying flood situations over 2014-2018 at seven different study sites in Fiji while jointly modelling the flood characteristics such as flood duration, volume, and peak using a vine copula model for probabilistic flood risk assessment.

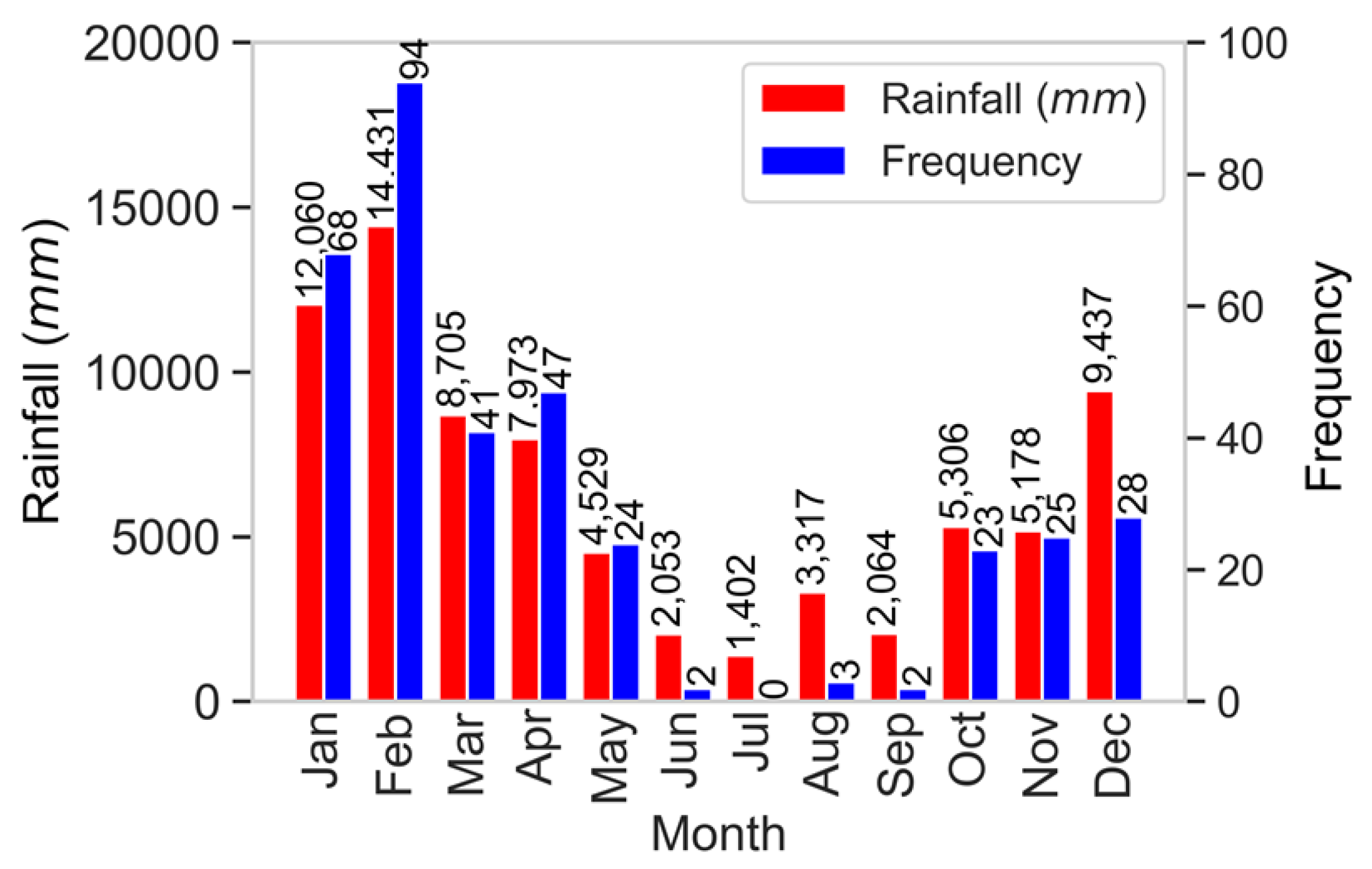

The results have unambiguously established the practical use of the newly proposed

as a potent indicator to identify the flood situation at an hourly scale while computing the associated flood characteristics that were impossible with a 24-hourly water resources index used in literature. The results also showed that Fiji mainly experienced high rainfall during the wet/cyclone season (November to April), including May and October. Consequently, the number of flood events was higher in these months than in the other months. This highlights the critical importance of implementing comprehensive and well-structured flood preparedness and risk mitigation strategies tailored explicitly for these months characterised by heightened rainfall and food events, thus ensuring the safety and security of communities and their properties. This study also presented the flood characteristics and water-intensive properties of five severe flood events for each study site. Relevant organisations, such as Fiji’s NDMO, are expected to use these findings to understand the attributes of past flood events at these study sites. This, in turn, can support future decision-making on flood mitigation, ultimately reducing the severe impacts of such events.

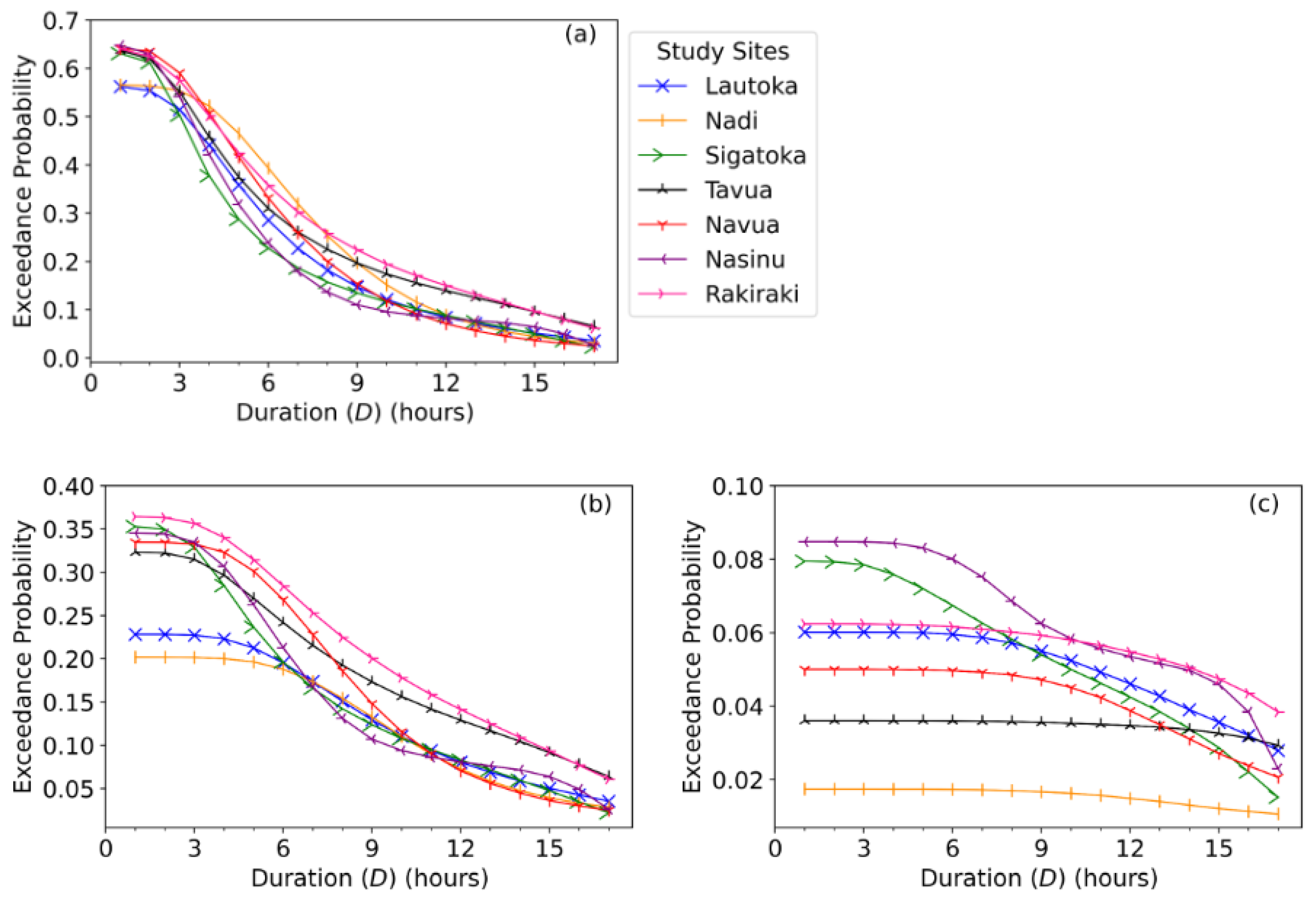

The correlation analysis showed a strong positive correlation among flood characteristics. Vine copulas were applied to model the joint distributions amongst the extreme flood characteristics derived from the hourly flood index to extract their joint exceedance probability, thus providing vital information for probabilistic flood risk assessment at each study site. The results revealed moderate variations in the spatial patterns of joint exceedance probability of extreme flood event characteristics across different combination scenarios, highlighting exceptionally low probabilities of floods with extreme duration, volume, and peak at all study sites.

Despite the merits of the present study, a primary limitation of this research was the unavailability of rainfall data required for many of the flood-prone sites across Fiji. Consequently, this research was confined to selected sites within the western and central divisions of the country. As a result, this study could not perform a comparative analysis across all four divisions (i.e., the western, central, northern, and eastern divisions), which could have provided valuable insights into extreme flood risk areas in the nation. It is important to note that the Ba study site in the western division of Fiji, a frequent flooding zone, had to be excluded due to a high percentage of missing rainfall data. Therefore, in future research, our methodology can be improved with

derived from satellite-based rainfall products covering a wider area, including major towns and cities, following the recent approach for Myanmar [

14].

Another limitation of the present study was using a prior/fixed time-dependent reduction function with the weighting factor,

W = 3.8, derived by the earlier study [

17], to determine the contributions of accumulated rainfall in the latest 24 hours. As discussed, the proposed

is a normalised version of an existing

that used a suitable time-dependent reduction function to account for the depletion of water resources through various hydrological processes. In future, further studies can test the correctness of this weighting factor more comprehensively for study sites where the topography may vary widely. This could require a major correlation of this weighting factor against rainfall-runoff and other physical models to capture more accurately the actual value of the decay of accumulated rainfall and its impacts on a flood event [

11,

17]. Several tests with hydrological parameters, including evapotranspiration rates, percolation, seepage, surface run-off and drainage conditions, etc., may be required to ascertain the time-dependent reduction function for the

. In regions with different decay rates of rainfall-accumulated water volume, it is crucial to incorporate them when formulating the

. The proposed

must also be verified for its broader adoption as an index-based risk monitoring tool. Therefore, its feasibility is expected to be demonstrated in other flood-prone regions globally in future studies, contingent on the availability of well-documented flood records for validation and hourly rainfall data.

This study has undertaken a purely mathematical-based approach to monitoring flood risk, so in future studies, it is anticipated that the proposed , in conjunction with additional data such as the catchment hydrology as well as drainage information, river flows, etc., are being utilised to develop hourly hydrograph for various sites. This approach will further cement the accuracy of flood characteristic estimation and the monitoring of flash flood events. There is also a potential to develop an innovative -based forecasting system with sufficient lead time, presenting a novel approach for early flash flood warnings in Fiji and other regions.

A key advantage of , as an hourly flood risk monitoring tool, is its simplistic mathematical formula that is easy to compute, analyse, and interpret for non-expert audiences compared to physical or hydrological models, including rainfall-runoff models for flood risk monitoring that involves complex development. However, in future, especially in varied hydrological and topographic settings, it is crucial to comprehensively compare the proposed with other established flood monitoring systems, including a Flash Flood Guidance System (FFGS).

Despite these limitations, using has demonstrated acceptable accuracy in detecting flood situations on an hourly scale. Therefore, our proposed methodology can be considered a feasible and cost-effective tool for hourly flood risk monitoring in Fiji and perhaps elsewhere with similar geographical locations. Applying the proposed probabilistic flood risk analysis using vine copula can enhance the nation’s overall flood risk assessment and mitigation strategies.

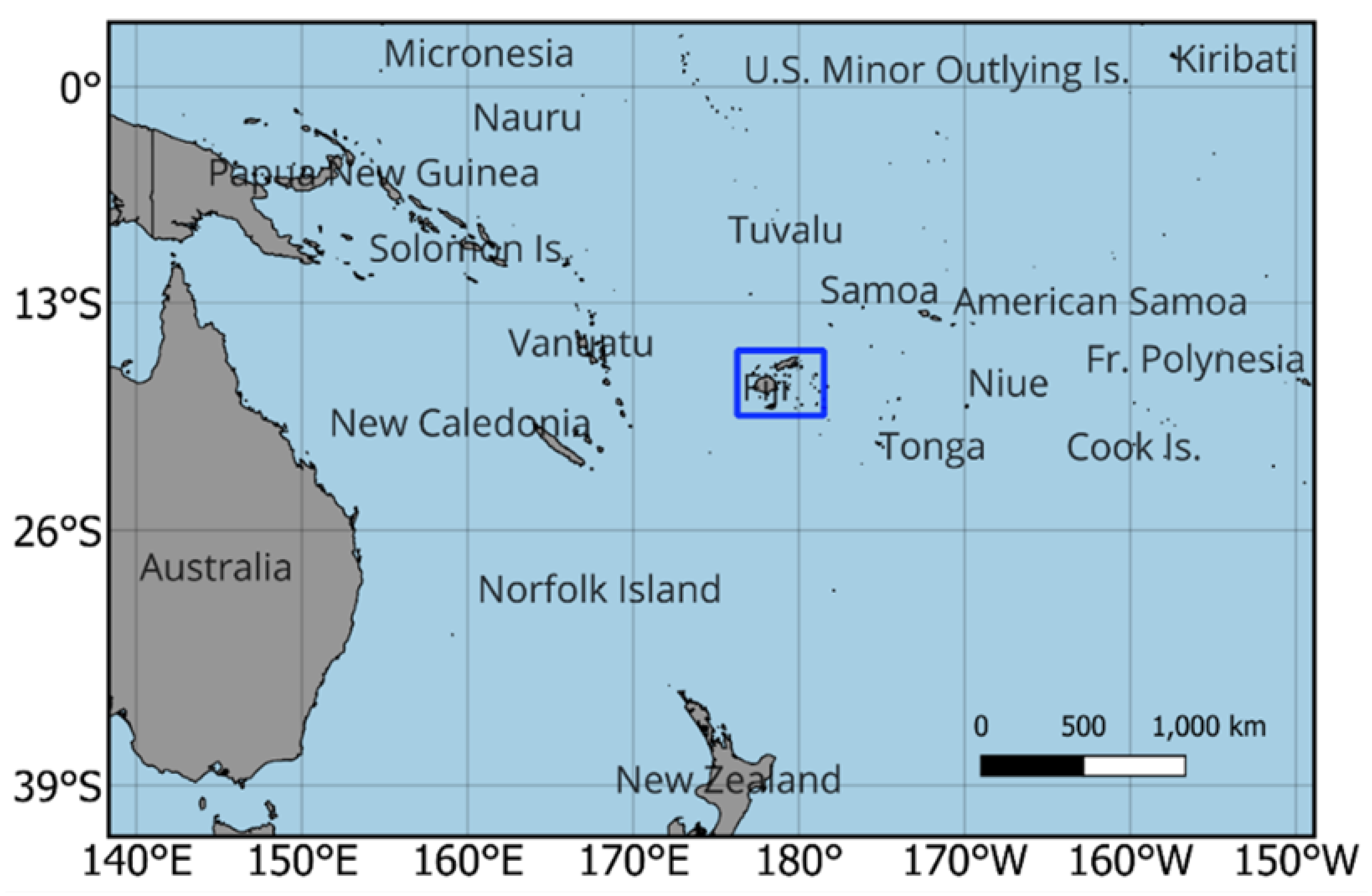

Figure 1.

The geographical map shows Fiji situated in the South Pacific region.

Figure 1.

The geographical map shows Fiji situated in the South Pacific region.

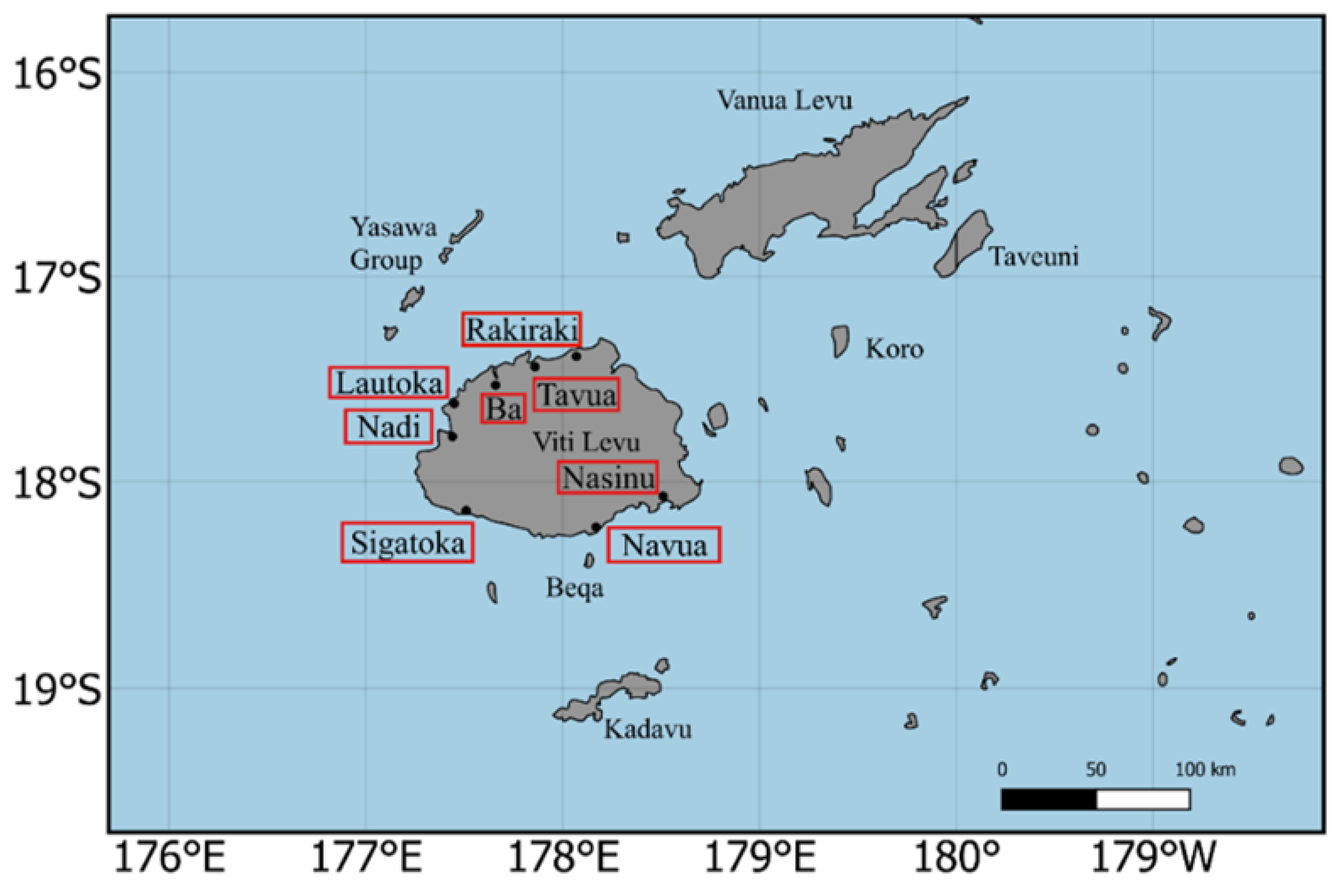

Figure 2.

The map of Fiji shows the various study sites.

Figure 2.

The map of Fiji shows the various study sites.

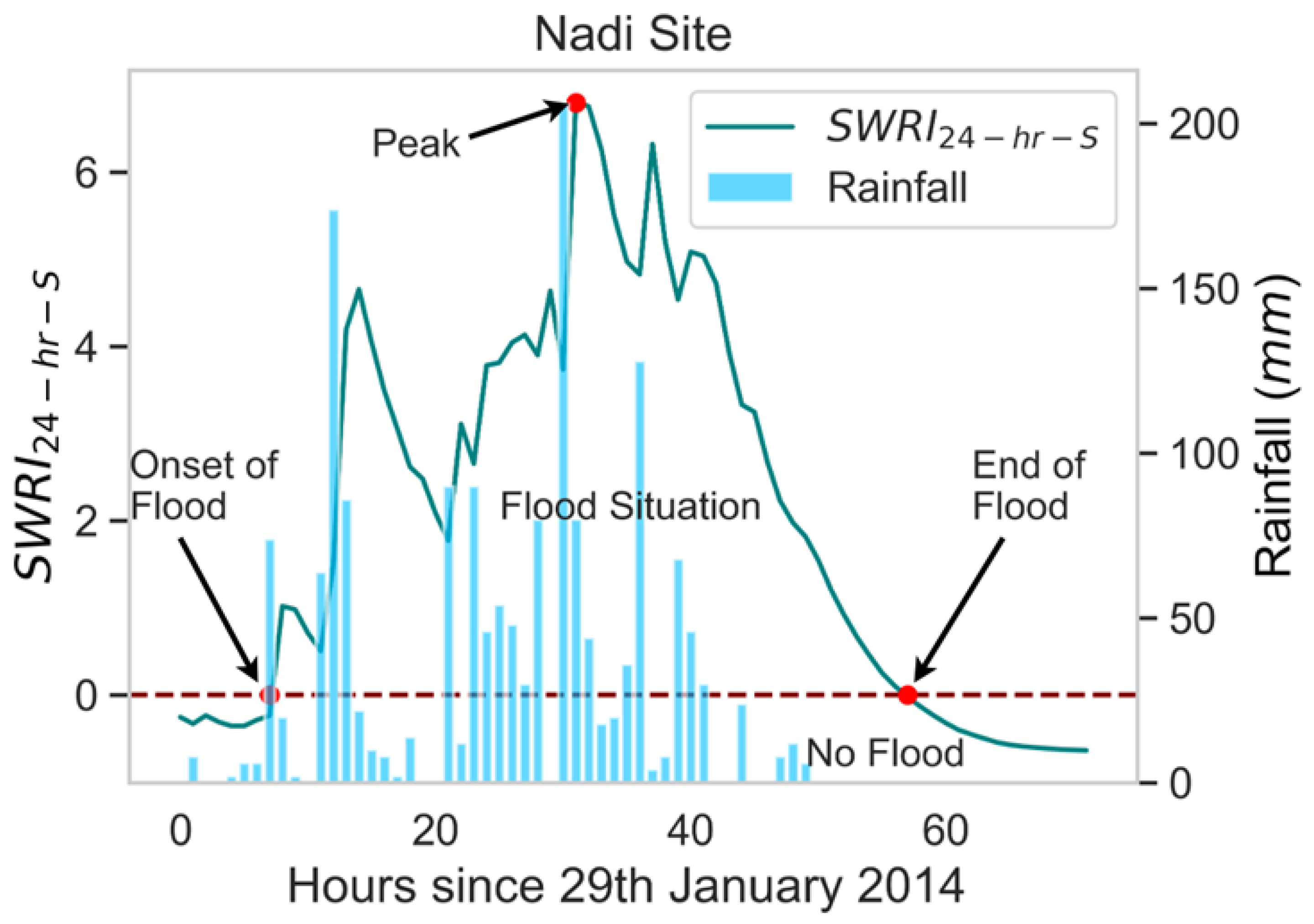

Figure 3.

The developed to identify a flood event in January 2014 at the Nadi study site demonstrating its capability to determine the duration, volume, and peak of any flood event. The flood volume, representing the accumulated water resources, is the cumulative under the curve closed by the onset and end of a flood situation and the zero line.

Figure 3.

The developed to identify a flood event in January 2014 at the Nadi study site demonstrating its capability to determine the duration, volume, and peak of any flood event. The flood volume, representing the accumulated water resources, is the cumulative under the curve closed by the onset and end of a flood situation and the zero line.

Figure 4.

The and rainfall since 29th of January 2014 (72 hours) for the Nadi site.

Figure 4.

The and rainfall since 29th of January 2014 (72 hours) for the Nadi site.

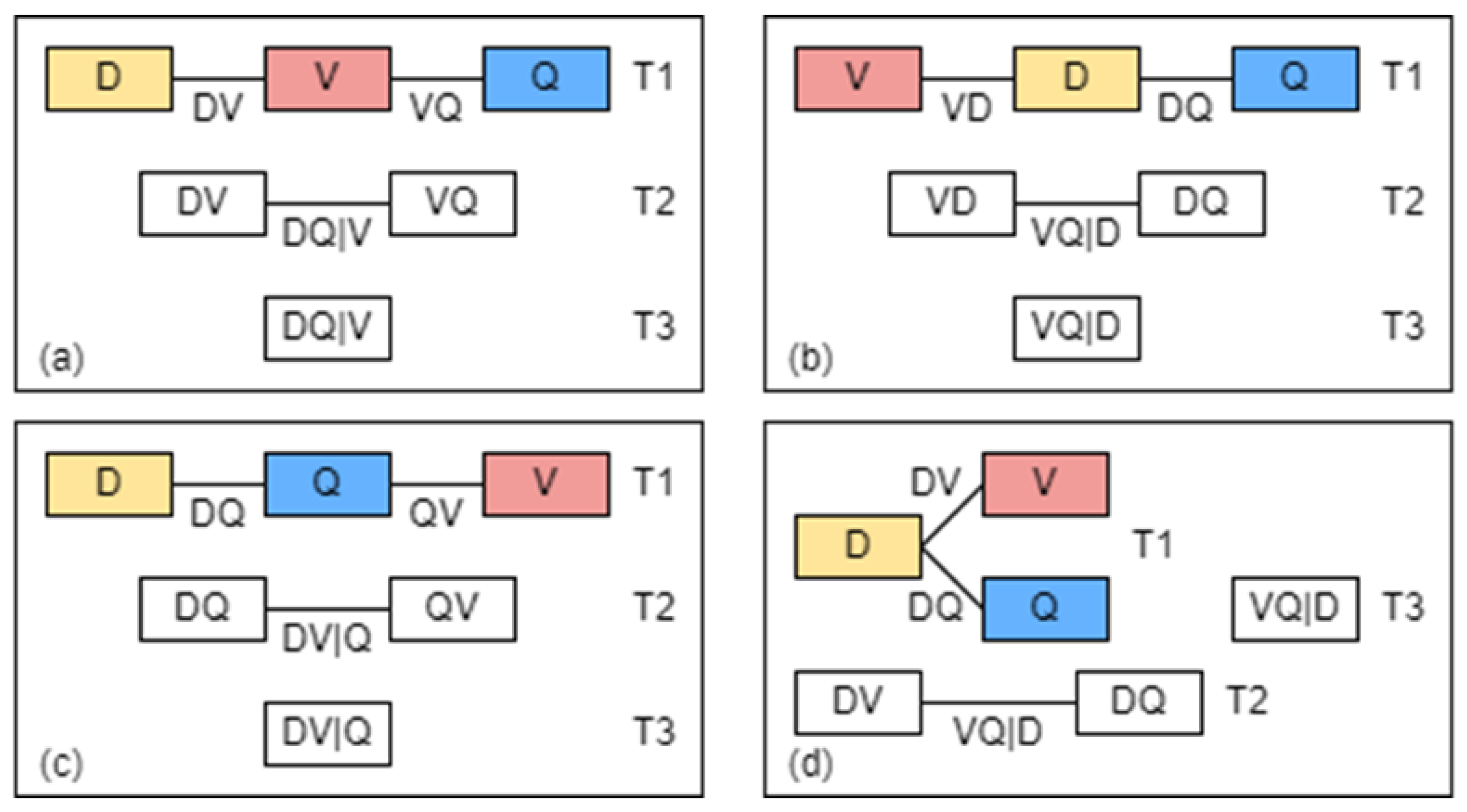

Figure 5.

An example of a 3-dimensional D-vine copula (

a-c) and a C-vine copula (

d). The vine copulas have 3 trees and 3 edges with duration (

D), volume (

V), and peak (

Q) as nodes, and each edge is associated with a pair-copula. Source: Adapted from Nguyen-Huy et al. [

14].

Figure 5.

An example of a 3-dimensional D-vine copula (

a-c) and a C-vine copula (

d). The vine copulas have 3 trees and 3 edges with duration (

D), volume (

V), and peak (

Q) as nodes, and each edge is associated with a pair-copula. Source: Adapted from Nguyen-Huy et al. [

14].

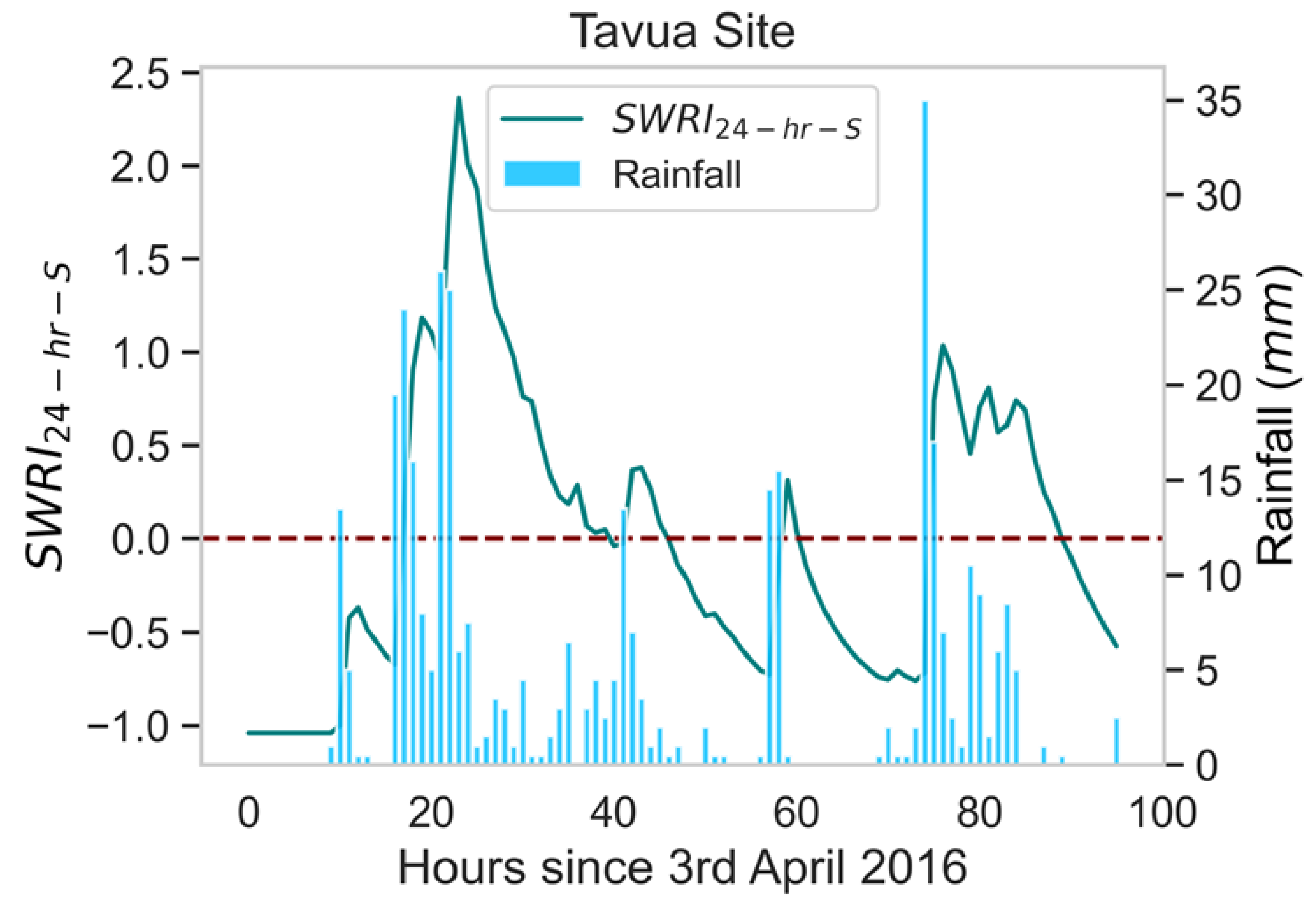

Figure 6.

The applied to identify the flood events in April 2016 at the Tavua site (96 hours).

Figure 6.

The applied to identify the flood events in April 2016 at the Tavua site (96 hours).

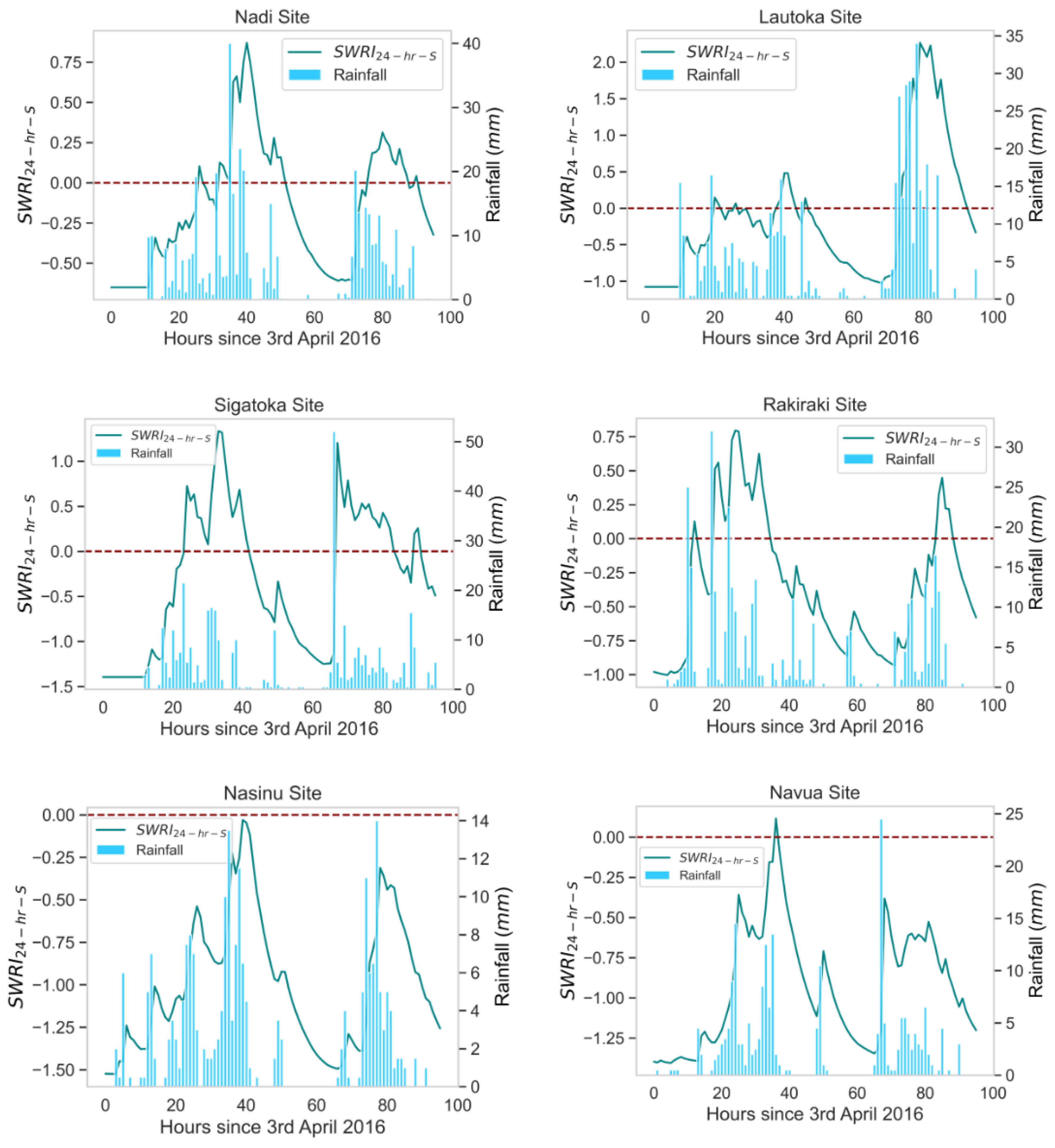

Figure 7.

The applied to identify the flood events in April 2016 at the other study sites (96 hours).

Figure 7.

The applied to identify the flood events in April 2016 at the other study sites (96 hours).

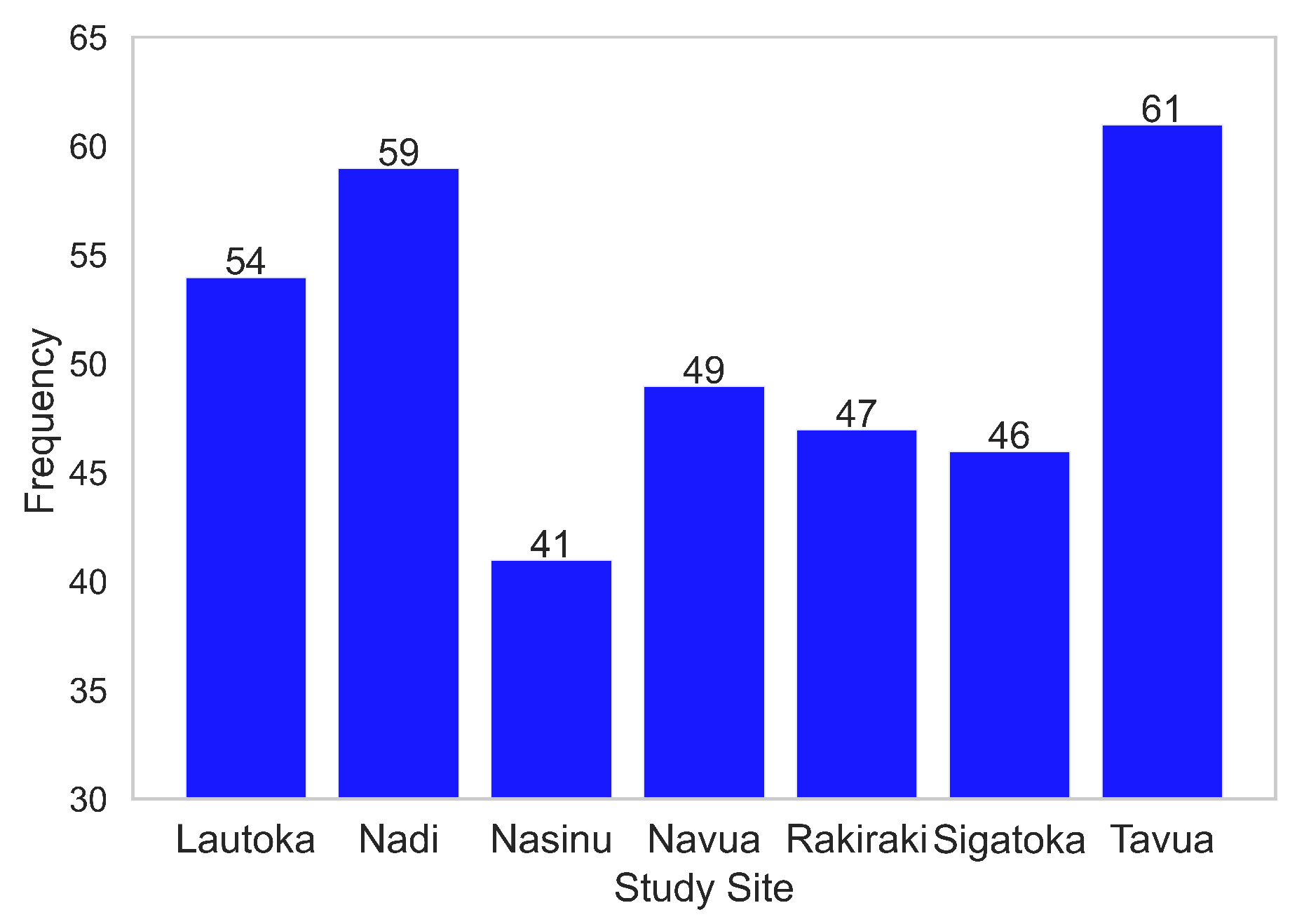

Figure 8.

Geographic analysis of flood frequency between 2014 and 2018.

Figure 8.

Geographic analysis of flood frequency between 2014 and 2018.

Figure 9.

Temporal (monthly) analysis of flood frequency and total monthly rainfall aggregated from 2014-2018.

Figure 9.

Temporal (monthly) analysis of flood frequency and total monthly rainfall aggregated from 2014-2018.

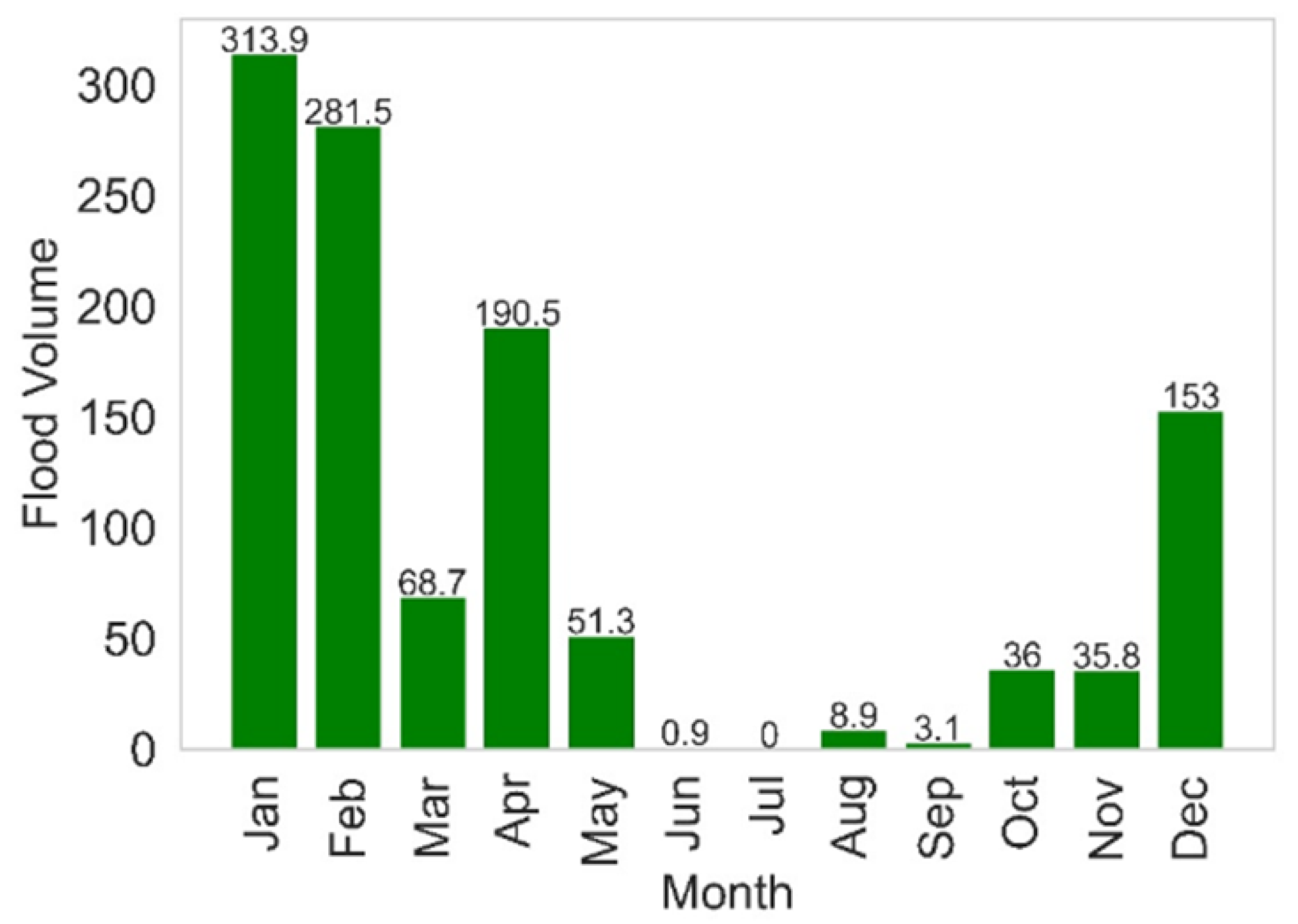

Figure 10.

Temporal (monthly) analysis of the combined volume of flood events across 7 study sites from 2014-2018.

Figure 10.

Temporal (monthly) analysis of the combined volume of flood events across 7 study sites from 2014-2018.

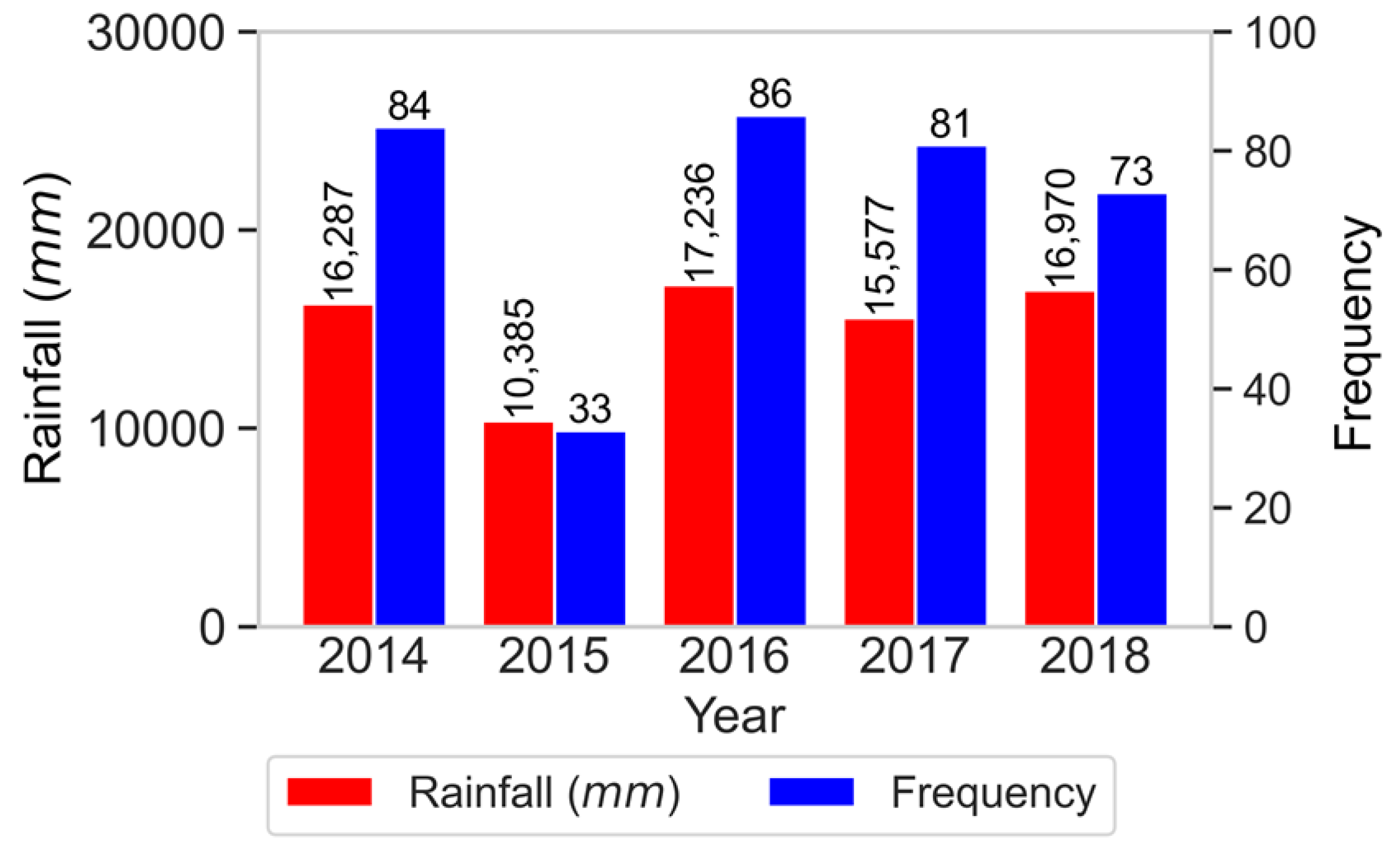

Figure 11.

Frequency of floods and total rainfall across 7 study sites aggregated from 2014 to 2018.

Figure 11.

Frequency of floods and total rainfall across 7 study sites aggregated from 2014 to 2018.

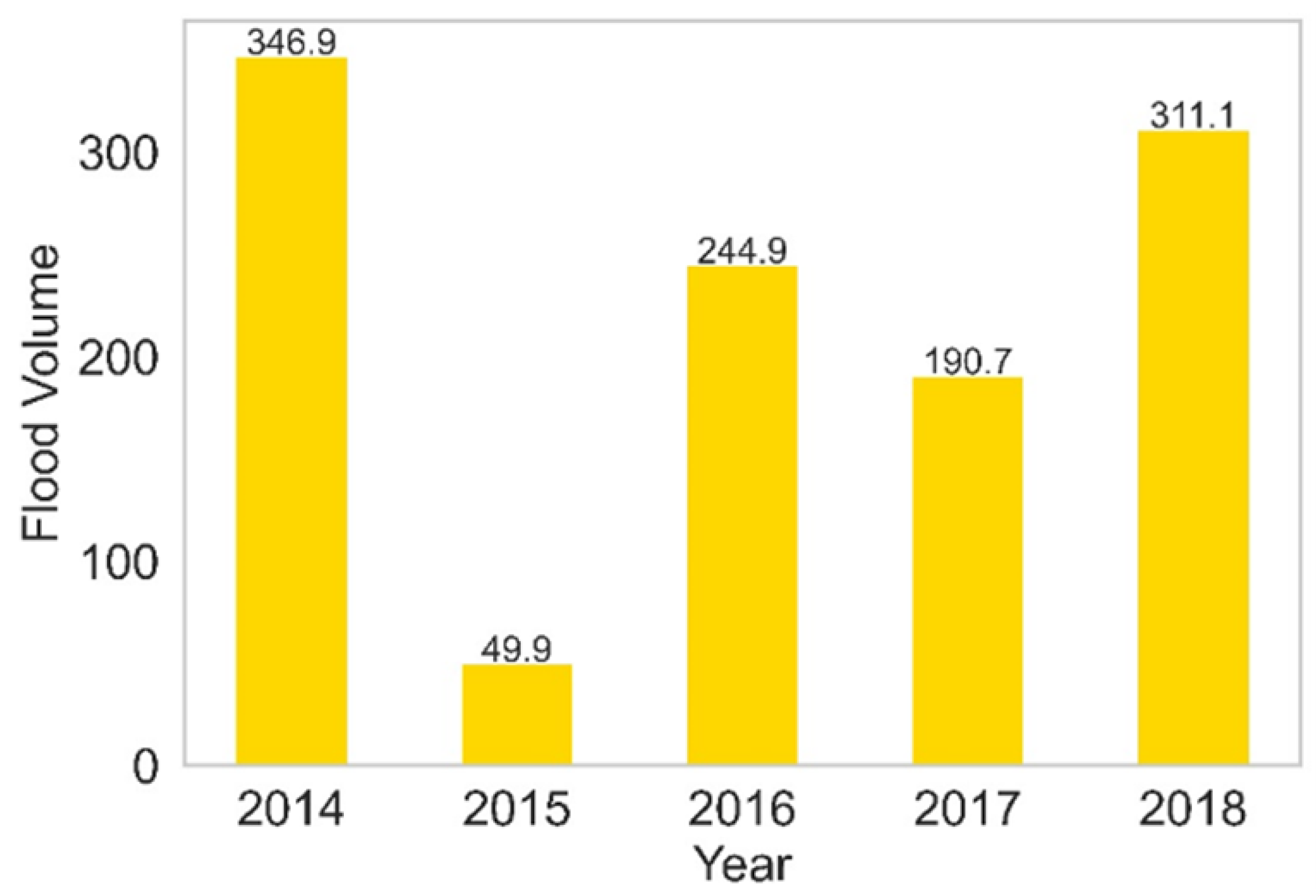

Figure 12.

Yearly combined volume of flood events across the 7 study sites from 2014 to 2018.

Figure 12.

Yearly combined volume of flood events across the 7 study sites from 2014 to 2018.

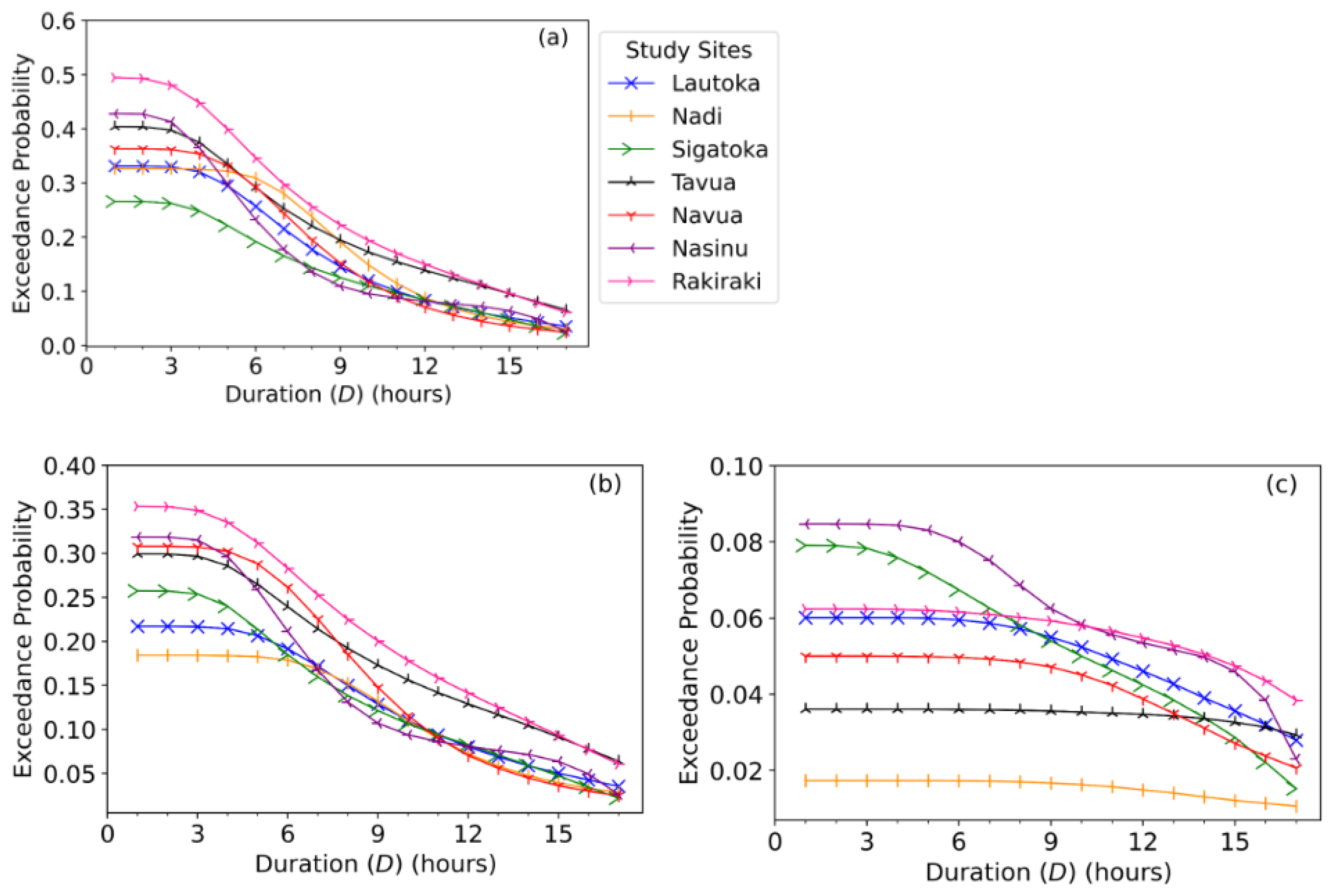

Figure 13.

The flood risk assessment presented in terms of the joint exceedance probability of a flood event’s duration (D) being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (median) (i.e., D ≥q (0.5) = 3 hours), 75th-quantile (moderate) (i.e., D≥q (0.75) = 6 hours), and 95th-quantile (extreme) (i.e., D≥q (0.95) = 15 hours) combined with: (a) both volume and peak being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.5) = 6.222 & Q≥q(0.5) = 0.352)), (b) volume being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.5) = 6.222 & Q≥q (0.75) = 0.821), (c) volume being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile (i.e., V≥ q (0.5) = 6.222 & Q≥ q (0.95) = 1.915).

Figure 13.

The flood risk assessment presented in terms of the joint exceedance probability of a flood event’s duration (D) being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (median) (i.e., D ≥q (0.5) = 3 hours), 75th-quantile (moderate) (i.e., D≥q (0.75) = 6 hours), and 95th-quantile (extreme) (i.e., D≥q (0.95) = 15 hours) combined with: (a) both volume and peak being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.5) = 6.222 & Q≥q(0.5) = 0.352)), (b) volume being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.5) = 6.222 & Q≥q (0.75) = 0.821), (c) volume being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile (i.e., V≥ q (0.5) = 6.222 & Q≥ q (0.95) = 1.915).

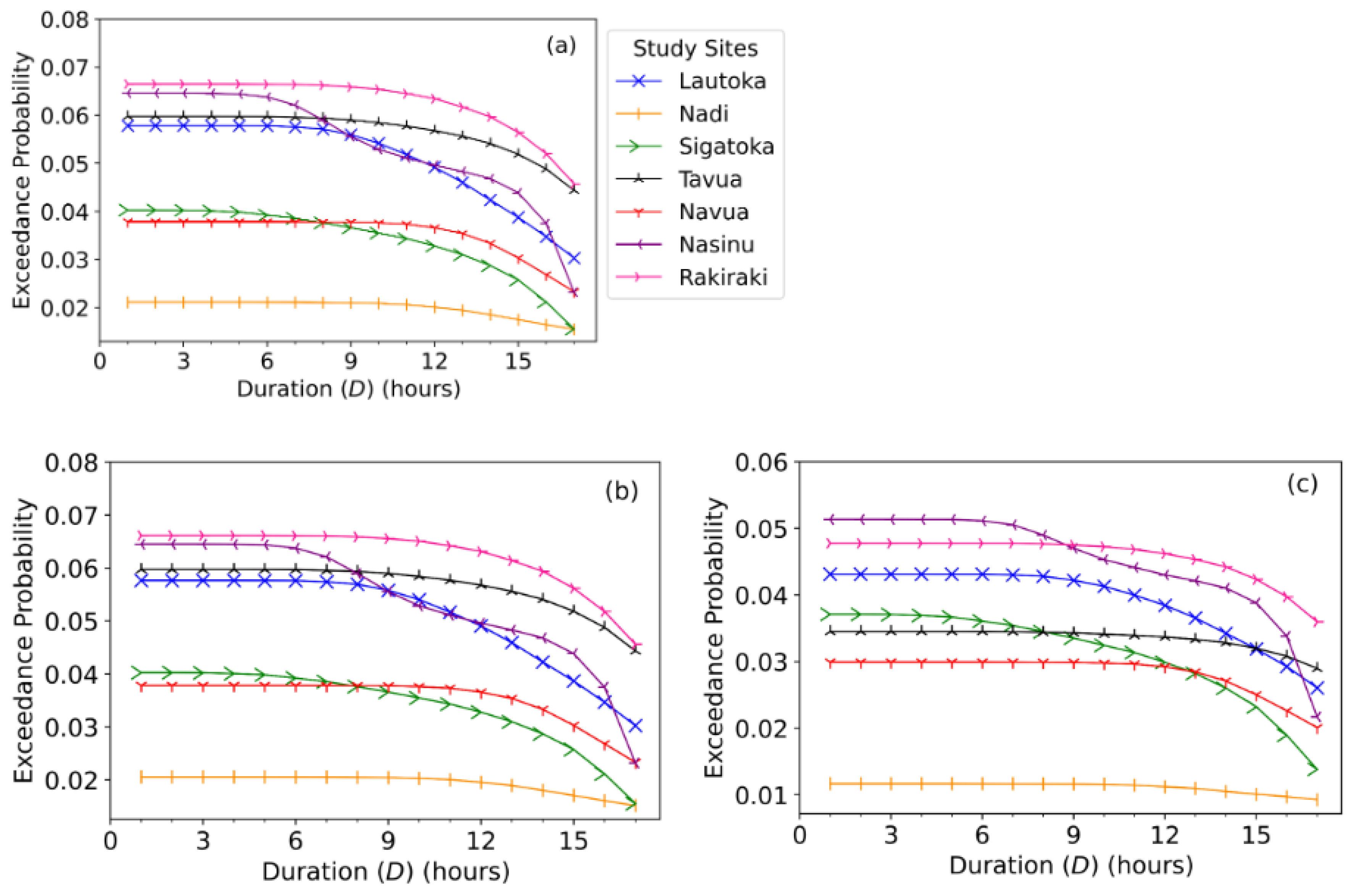

Figure 14.

The flood risk assessment presented in terms of the joint exceedance probability of flood duration (D) being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (median) (i.e., D ≥q (0.5) = 3 hours), 75th-quantile (moderate) (i.e., D≥q (0.75) = 6 hours), and 95th-quantile (extreme) (i.e.,D≥q (0.95) = 15 hours) combined with: (a) volume being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.75) = 2.473 & Q≥q (0.5) = 0.352), (b) both volume and peak being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.75) = 2.473 & Q≥q (0.75) = 0.821), (c) volume being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.75) = 2.473 & Q≥ q (0.95) = 1.915).

Figure 14.

The flood risk assessment presented in terms of the joint exceedance probability of flood duration (D) being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (median) (i.e., D ≥q (0.5) = 3 hours), 75th-quantile (moderate) (i.e., D≥q (0.75) = 6 hours), and 95th-quantile (extreme) (i.e.,D≥q (0.95) = 15 hours) combined with: (a) volume being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.75) = 2.473 & Q≥q (0.5) = 0.352), (b) both volume and peak being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.75) = 2.473 & Q≥q (0.75) = 0.821), (c) volume being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.75) = 2.473 & Q≥ q (0.95) = 1.915).

Figure 15.

The flood risk assessment presented in terms of the joint exceedance probability of flood duration (D) being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (median) (i.e., D ≥q (0.5) = 3 hours), 75th-quantile (moderate) (i.e., D≥q (0.75) = 6 hours), and 95th-quantile (extreme) (i.e., D≥q (0.95) = 15 hours) combined with: (a) volume being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.95) = 12.799 & Q≥q (0.5) = 0.352), (b) volume being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.95) = 12.799 & Q≥q (0.75) = 0.821), (c) both volume and peak being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.95) = 12.799 & Q≥ q(0.95) = 1.915).

Figure 15.

The flood risk assessment presented in terms of the joint exceedance probability of flood duration (D) being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (median) (i.e., D ≥q (0.5) = 3 hours), 75th-quantile (moderate) (i.e., D≥q (0.75) = 6 hours), and 95th-quantile (extreme) (i.e., D≥q (0.95) = 15 hours) combined with: (a) volume being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 50th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.95) = 12.799 & Q≥q (0.5) = 0.352), (b) volume being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile and peak being greater than or equal to 75th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.95) = 12.799 & Q≥q (0.75) = 0.821), (c) both volume and peak being greater than or equal to 95th-quantile (i.e., V≥q (0.95) = 12.799 & Q≥ q(0.95) = 1.915).

Table 1.

Geographic settings and the relevant metadata of hourly rainfall for the different study sites. Note that the hourly rainfall spans from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018, with 43,824 expected observations.

Table 1.

Geographic settings and the relevant metadata of hourly rainfall for the different study sites. Note that the hourly rainfall spans from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018, with 43,824 expected observations.

| Study Site |

Location |

Missing Data |

Average |

Maximum |

| |

|

(%) |

Hourly Rainfall (mm)

|

Hourly Rainfall (mm)

|

| Ba |

17.53 °S, 177.66 °E |

23.76 |

0.24 |

56.00 |

| Lautoka |

17.62 °S, 177.45 °E |

0.83 |

0.19 |

83.50 |

| Nadi |

17.78 °S, 177.44 °E |

1.17 |

0.27 |

260.00 |

| Nasinu |

18.07 °S, 178.51 °E |

1.18 |

0.33 |

72.00 |

| Navua |

18.22 °S, 178.17 °E |

1.57 |

0.36 |

62.50 |

| Rakiraki |

17.39 °S, 178.07 °E |

3.76 |

0.23 |

68.50 |

| Sigatoka |

18.14 °S, 177.51 °E |

1.99 |

0.21 |

59.00 |

| Tavua |

17.44 °S, 177.86 °E |

3.45 |

0.16 |

57.50 |

Table 2.

Analysis of the 5 severest flood events for different study sites in Fiji from 2014 to 2018. (a) Nadi, (b) Lautoka, (c) Nasinu, (d) Navua, (e) Rakiraki, (f) Sigatoka, (g) Tavua. Note that D = total number of hours between start and end of a flood event, V = sum of between start and end, and Q = maximum during a flood situation as per Eqs. 4-6.

Table 2.

Analysis of the 5 severest flood events for different study sites in Fiji from 2014 to 2018. (a) Nadi, (b) Lautoka, (c) Nasinu, (d) Navua, (e) Rakiraki, (f) Sigatoka, (g) Tavua. Note that D = total number of hours between start and end of a flood event, V = sum of between start and end, and Q = maximum during a flood situation as per Eqs. 4-6.

| Study Site |

|

Onset Time |

Volume |

Duration |

Peak |

Total |

Total Rain |

Maximum |

| |

|

() |

() |

() (hrs) |

() |

|

(mm)

|

|

| a |

Nadi |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

1 |

29-01-2014 at 8 a.m. |

157.28 |

49 |

6.80 |

10557.06 |

1590 |

416.05 |

| |

2 |

08-02-2017 at 4 a.m. |

11.88 |

18 |

1.31 |

1316.32 |

195.40 |

109.56 |

| |

3 |

04-04-2016 at 8 a.m. |

6.86 |

20 |

0.87 |

1108.52 |

161.40 |

84.87 |

| |

4 |

07-01-2014 at 6 p.m. |

6.31 |

10 |

1.73 |

715.09 |

84 |

133.10 |

| |

5 |

15-01-2014 at 6 p.m. |

5.77 |

13 |

1.18 |

794.02 |

84 |

102.03 |

| b |

Lautoka |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

1 |

14-01-2018 at 2 p.m. |

25.05 |

19 |

3.29 |

1315.15 |

175 |

126.10 |

| |

2 |

06-04-2016 at 2 a.m. |

23.95 |

19 |

2.27 |

1283.34 |

180 |

96.59 |

| |

3 |

01-04-2014 at 7 a.m. |

18.39 |

13 |

3.49 |

935.98 |

109 |

131.92 |

| |

4 |

06-02-2017 at 3 p.m. |

11.48 |

20 |

1.53 |

954.55 |

131.50 |

75.40 |

| |

5 |

08-02-2017 at 9 a.m. |

10.85 |

13 |

1.49 |

718.16 |

98 |

74.18 |

| c |

Nasinu |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

1 |

27-02-2014 at 9 a.m. |

24.90 |

18 |

2.83 |

1388.83 |

173 |

115.53 |

| |

2 |

21-02-2015 at 6 p.m. |

23.15 |

16 |

2.48 |

1261.37 |

163.50 |

106.16 |

| |

3 |

06-12-2014 at 4 a.m. |

19.15 |

16 |

2.92 |

1155.37 |

140 |

117.79 |

| |

4 |

11-11-2018 at 11 p.m. |

7.46 |

8 |

1.91 |

521.64 |

37 |

91.16 |

| |

5 |

28-05-2018 at 8 a.m. |

7.20 |

7 |

2.10 |

474.23 |

21 |

96.15 |

| d |

Navua |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

1 |

15-12-2016 at 6 a.m. |

56.98 |

28 |

4.29 |

2732.99 |

392.50 |

161.35 |

| |

2 |

17-03-2017 at 4 a.m. |

16.37 |

14 |

2.10 |

1023.68 |

114.50 |

99.48 |

| |

3 |

16/01/2014 at 1 a.m. |

9.82 |

14 |

1.16 |

838.28 |

123.50 |

72.87 |

| |

4 |

02-05-2016 at 6 a.m. |

8.15 |

13 |

1.38 |

751.01 |

110 |

79.03 |

| |

5 |

27-02-2014 at 3 p.m. |

7.98 |

10 |

1.61 |

626.25 |

83.50 |

85.60 |

| |

1 |

19-12-2016 at 5 a.m. |

33.99 |

21 |

4.28 |

1783.89 |

265.50 |

170.39 |

| |

2 |

14-01-2018 at 2 p.m. |

19.89 |

17 |

2 |

1199.35 |

156.50 |

97.02 |

| |

3 |

20-02-2016 at 8 p.m. |

16.89 |

17 |

2.68 |

1103.01 |

112.50 |

119.05 |

| |

4 |

17-12-2016 at 4 p.m. |

11.28 |

19 |

1.25 |

989.33 |

145.50 |

73.09 |

| |

5 |

05-03-2017 at 9 a.m. |

10.06 |

15 |

1.52 |

818.03 |

114.50 |

81.73 |

| f |

Sigatoka |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

1 |

30-01-2014 at 10 a.m. |

23.32 |

16 |

2.84 |

999.93 |

121 |

92.83 |

| |

2 |

03-02-2018 at 3 p.m. |

15 |

12 |

2.25 |

695.39 |

93 |

79.78 |

| |

3 |

01-05-2018 at 6 p.m. |

11.10 |

14 |

1.67 |

671.12 |

65 |

67.25 |

| |

4 |

04-04-2016 at 12 a.m. |

10.91 |

18 |

1.33 |

789.16 |

103 |

59.79 |

| |

5 |

01-04-2018 at 6 a.m. |

9.74 |

11 |

1.55 |

549.66 |

73 |

64.62 |

| g |

Tavua |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

1 |

08-02-2017 at 10 a.m. |

45.88 |

23 |

4.04 |

1612.79 |

238 |

117.34 |

| |

2 |

03-04-2016 at 5 p.m. |

20.37 |

23 |

2.36 |

1023.74 |

154 |

78.55 |

| |

3 |

17-05-2014 at 10 a.m. |

17.16 |

17 |

1.81 |

805.30 |

103.50 |

65.93 |

| |

4 |

06-02-2017 at 11 a.m. |

14.77 |

18 |

1.69 |

774.08 |

89.50 |

63.11 |

| |

5 |

06-03-2017 at 1 p.m. |

14.23 |

17 |

1.75 |

737.52 |

98.50 |

64.47 |

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of flood characteristics at each study site. Note that D = total number of hours between start and end of a flood event, V = sum of between start and end, and Q = maximum during a flood situation as per Eq. 4-6.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of flood characteristics at each study site. Note that D = total number of hours between start and end of a flood event, V = sum of between start and end, and Q = maximum during a flood situation as per Eq. 4-6.

| Flood Characteristic |

Site |

Min. |

Lower Quartile (Q1) |

Median (Q2) |

Upper Quartile (Q3) |

Max. |

Mean |

Standard Dev. |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

| Duration (D) (hours) |

Lautoka |

1 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

20 |

4.796 |

4.791 |

1.771 |

5.511 |

| |

Nadi |

1 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

49 |

5.424 |

7.135 |

4.286 |

24.981 |

| |

Rakiraki |

1 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

21 |

5.681 |

5.801 |

1.248 |

3.243 |

| |

Tavua |

1 |

2 |

3 |

7 |

23 |

5.525 |

5.749 |

1.590 |

4.492 |

| |

Sigatoka |

1 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

18 |

4.413 |

4.578 |

1.746 |

4.848 |

| |

Navua |

1 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

28 |

4.367 |

5.003 |

2.753 |

11.676 |

| |

Nasinu |

1 |

2 |

3 |

6 |

18 |

4.415 |

4.153 |

1.962 |

6.236 |

| Volume (V) |

Lautoka |

0.003 |

0.204 |

0.633 |

1.983 |

25 |

2.746 |

5.473 |

3.022 |

11.168 |

| |

Nadi |

0.002 |

0.132 |

0.517 |

2.271 |

157.276 |

4.156 |

20.404 |

7.538 |

55.625 |

| |

Rakiraki |

0.005 |

0.097 |

0.529 |

3.038 |

33.993 |

3.272 |

6.329 |

3.257 |

13.998 |

| |

Tavua |

0.016 |

0.185 |

0.617 |

2.272 |

45.879 |

3.190 |

7.123 |

4.230 |

22.984 |

| |

Sigatoka |

0.021 |

0.220 |

0.632 |

2.834 |

23.316 |

2.826 |

4.777 |

2.523 |

9.293 |

| |

Navua |

0.005 |

0.167 |

0.557 |

2.058 |

56.983 |

3.012 |

8.495 |

5.656 |

34.803 |

| |

Nasinu |

0.033 |

0.159 |

0.886 |

2.854 |

24.903 |

3.028 |

5.853 |

2.951 |

10.098 |

| Peak (Q) |

Lautoka |

0.003 |

0.179 |

0.348 |

0.701 |

3.490 |

0.597 |

0.725 |

2.519 |

9.356 |

| |

Nadi |

0.002 |

0.108 |

0.244 |

0.674 |

6.803 |

0.527 |

0.940 |

5.369 |

35.042 |

| |

Rakiraki |

0.005 |

0.097 |

0.323 |

0.816 |

4.282 |

0.606 |

0.809 |

2.663 |

10.954 |

| |

Tavua |

0.016 |

0.124 |

0.338 |

0.799 |

4.040 |

0.573 |

0.688 |

2.719 |

12.339 |

| |

Sigatoka |

0.021 |

0.207 |

0.393 |

1.121 |

2.841 |

0.718 |

0.714 |

1.369 |

3.945 |

| |

Navua |

0.005 |

0.167 |

0.401 |

0.723 |

4.289 |

0.601 |

0.747 |

2.924 |

13.398 |

| |

Nasinu |

0.033 |

0.139 |

0.419 |

0.916 |

2.915 |

0.720 |

0.763 |

1.566 |

4.596 |

Table 4.

The statistical correlation in terms of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient () computed between the pairs of various flood characteristics in respect to the Duration (D, in hours), Volume (V) and Peak (Q) for each study site. D = total number of hours between start and end of a flood event, V = sum of between start and end and Q = maximum during a flood situation (see Eq. 4-6).

Table 4.

The statistical correlation in terms of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient () computed between the pairs of various flood characteristics in respect to the Duration (D, in hours), Volume (V) and Peak (Q) for each study site. D = total number of hours between start and end of a flood event, V = sum of between start and end and Q = maximum during a flood situation (see Eq. 4-6).

| Study Site |

D & V

|

D & Q

|

V & Q

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lautoka |

0.895 |

0.941 |

0.860 |

0.877 |

0.931 |

0.971 |

| Nadi |

0.863 |

0.950 |

0.929 |

0.891 |

0.924 |

0.978 |

| Rakiraki |

0.855 |

0.934 |

0.842 |

0.902 |

0.949 |

0.987 |

| Sigatoka |

0.895 |

0.929 |

0.810 |

0.869 |

0.887 |

0.979 |

| Tavua |

0.838 |

0.946 |

0.859 |

0.902 |

0.942 |

0.960 |

| Navua |

0.891 |

0.937 |

0.937 |

0.892 |

0.899 |

0.982 |

| Nasinu |

0.942 |

0.945 |

0.895 |

0.844 |

0.896 |

0.964 |

Table 5.

The duration (D) (hours), volume (V), and peak (Q) at the 50th-quantile (median), 75th-quantile (moderate), and 95th-quantile (extreme) for each study site.

Table 5.

The duration (D) (hours), volume (V), and peak (Q) at the 50th-quantile (median), 75th-quantile (moderate), and 95th-quantile (extreme) for each study site.

| Flood Characteristic |

Study Site |

50th-quantile |

75th-quantile |

95th-quantile |

|

D (hours) |

Lautoka |

3 |

6 |

15 |

| |

Nadi |

3 |

7 |

13 |

| |

Rakiraki |

3 |

8 |

17 |

| |

Tavua |

3 |

7 |

17 |

| |

Sigatoka |

3 |

5 |

16 |

| |

Navua |

3 |

5 |

14 |

| |

Nasinu |

3 |

6 |

16 |

| |

Average |

3 |

6 |

15 |

| V |

Lautoka |

0.633 |

1.983 |

13.898 |

| |

Nadi |

0.517 |

2.271 |

6.365 |

| |

Rakiraki |

0.529 |

3.038 |

15.205 |

| |

Tavua |

0.617 |

2.272 |

14.767 |

| |

Sigatoka |

0.632 |

2.834 |

11.054 |

| |

Navua |

0.557 |

2.058 |

9.149 |

| |

Nasinu |

0.866 |

2.854 |

19.153 |

| |

Average |

0.622 |

2.473 |

12.799 |

| Q |

Lautoka |

0.348 |

0.701 |

1.840 |

| |

Nadi |

0.244 |

0.674 |

1.365 |

| |

Rakiraki |

0.323 |

0.816 |

1.976 |

| |

Tavua |

0.338 |

0.799 |

1.750 |

| |

Sigatoka |

0.393 |

1.121 |

2.305 |

| |

Navua |

0.401 |

0.723 |

1.694 |

| |

Nasinu |

0.419 |

0.916 |

2.477 |

| |

Average |

0.352 |

0.821 |

1.915 |