1. Introduction

Agents to modify checkpoint inhibition by PD-L1 (programmed death ligand 1) and its immune cell receptor (PD-1) are widely used to treat malignant melanoma and other malignancies. However, response to treatment is unpredictable and may not be sustained [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Treatment with exogenous activated Arylsulfatase B (ARSB; N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase), the enzyme that removes 4-sulfate groups at the non-reducing end from chondroitin 4-sulfate (C4S), was recently shown to reduce tumor progression and improve the survival of C57BL/6J mice with B16F10 subcutaneous melanomas [

6]. The potential impact of ARSB on PD-L1 expression and on PD-L1-mediated checkpoint therapy was unknown.

In prior work, decline in ARSB was associated with increasing invasiveness of human melanoma cell lines, as well as with more aggressive human prostate and colonic cancers and in association with malignant mammary cells [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. As ARSB decreases, chondroitin 4-sulfation increases, leading to increased binding of SHP2 (PTP11; non-receptor tyrosine phosphatase) and reduced binding of galectin-3 with C4S [

11,

12,

13]. Subsequent effects attributed to decline in SHP2 availability include increases in phospho-ERK1/2 and phospho-p38 MAPK and transcriptional effects, including by hypermethylation of the DKK3 promoter and reduced expression of DKK (Dickkopf WNT pathway signaling inhibitor) 3, leading to activation of Wnt signaling in prostate cells [

14]. Other transcriptional events following silencing of ARSB and increased availability of galectin-3 include the increased expression of CSPG4 and CHST15 in melanoma cells [

6,

7], increased expression of versican in prostate epithelial cells [

13], and increased expression of Wnt9A in colonic epithelial cells [

15]. The transcriptional events initiated by changes in SHP2 or galectin-3 binding with C4S, which follow either decline or increase in ARSB activity, exerted profound effects on vital cell processes. The relationship between these ARSB-C4S-initiated transcriptional mechanisms and immune-mediated effects on melanoma tumor proliferation had not been addressed previously.

Initial experiments showed that silencing ARSB in melanoma cells increased the expression of PD-L1 mRNA and protein and, inversely, treatment by exogenous ARSB reduced PD-L1 expression in human and mouse melanoma cells, as well as in human prostate cell lines [

16]. The experiments detailed in this report were performed to clarify the mechanism by which ARSB regulated PD-L1 expression in the subcutaneous B16F10 mouse melanomas, in human A375 melanoma cells, and in normal human melanocytes.

Reports in the literature have presented several different transcriptional mechanisms affecting PD-L1 expression, including epigenetic mechanisms involving methylations and histone deacetylations, as well as transcription factors [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. HDACs 3, 6, and 8 have been implicated in effects on histone acetylation in melanoma [

18,

24,

30,

31,

32,

34,

35]. Changes in ARSB or chondroitin-4 sulfate had not previously been associated with regulation of histone acetylation and HDACs. The findings which follow support the impact of ARSB and chondroitin 4-sulfation on galectin-3, c-jun, HDAC3, and H3 on the regulation of PD-L1 expression in melanoma and suggest that attention to ARSB may help to inform treatment decisions about checkpoint inhibition.

3. Discussion

Initial measurements of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) in human prostate cell lines, including metastatic PC-3 cells, normal prostate epithelial cells, and normal prostate stromal cells, showed that PD-L1 mRNA expression increased to 1.8 times, 2.2 times, and 1.6 times the baseline level when ARSB was silenced (

Supplementary Figure 1a). Other measurements indicated that in mononuclear cells of participants with prediabetes in a dietary study of carrageenan withdrawal [

45], PD-L1 expression declined by 62% in participants on the no-carrageenan diet over a 12-week period, as ARSB activity increased by 34% (

Supplementary Figure 1b). These findings indicated significant impact of ARSB on PD-L1 expression in other human cells and are consistent with the findings in this report about the effects of both ARSB knockdown and exogenous, bioactive ARSB on PD-L1 expression through an epigenetic mechanism.

PD-L1 has emerged as a major focus in immune-mediated control of tumor proliferation. The PD-1 – PD-L1 binding between tumor-invading immune cells and tumor cells has been elucidated as a checkpoint which impedes other, potentially more cytotoxic, immune cell-tumor cell interactions from proceeding. Many excellent clinical responses arise from treatment by checkpoint inhibitors using antibodies directed at either PD-1 or PD-L1; however, responses may not endure, some patients do not respond, and treatment toxicity may be severe [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Recognition that exogenous ARSB reduces PD-L1 expression may help to focus interest and treatment on the impact of chondroitin sulfate- and sulfatase-mediated effects in cancer biology and on regulation of immune-mediated effects.

Recent work has demonstrated that exogenous, bioactive ARSB reduces progression and improves survival of mice with B16F10 subcutaneous melanomas is provocative [

6], and further evaluation of the potential therapeutic benefit of exogenous ARSB treatment is of interest. Treatment benefit from rhARSB occurred at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg SQ on days 2, 7, and 14 post tumor inoculation, with no evidence of toxicity. Recombinant human ARSB is used successfully in enzyme replacement therapy of the congenital deficiency of ARSB, Mucopolysaccharidosis VI, by administration of a weekly dose of 1.0 mg/kg IV [

46].

In cultured prostate stem and epithelial cells, effects of ARSB on signaling events, including increase in phospho-JNK, were attributed to enhanced binding of SHP2 with C4S when ARSB activity was reduced, leading to sustained phosphorylation of vital signaling molecules [

12,

13,

14,

15]. In the current experiments, the SHP2 inhibitor PHPS1 had no impact on PD-L1 expression, and did not affect nuclear c-Jun, phospho-JNK, or HDAC activity. The pathway by which phospho-JNK is modified in the melanoma cells appears to be independent of SHP2 and is not yet clarified. The epigenetic mechanism in the melanoma cells affecting PD-L1 expression resembles the previously observed mechanisms by which ARSB and chondroitin 4-sulfation affect galectin-3 and AP-1, as shown with transcriptional effects on HIF-1α and versican [

11,

13]. The impact of ARSB on chondroitin 4-sulfation and, thereby, on binding of galectin-3 and restriction of free galectin-3 leads to exogenous ARSB acting as an inhibitor of galectin-3. Inhibition of galectin-3 is under investigation as a treatment approach to interfere with PD-1-PD-L1 interaction in melanoma and other malignancies [

47,

48,

49,

50]. Additional, detailed investigations are required to elucidate further how ARSB-induced changes in C4S impact on galectin-3, c-Jun, HDACs, and histones, potentially regulating multiple transcriptional events sites and malignant progression.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

A375 human melanoma cells (CRL-1619, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; ATCC), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (ATCC). The cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 environment with media exchange every 2 days. Confluent cells in T-25 flasks were harvested by EDTA-trypsin (ATCC), and sub-cultured. Primary normal melanocytes were cultured in Airway Epithelial cell basal medium (ATCC, Manassas, VA) with melanocyte growth kit (ATCC). The cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 environment with media exchange every 3 days. Confluent cells in T-25 flasks were harvested by trypsin for primary cells (ATCC) and sub-cultured. B16F10 mouse melanoma cells were purchased (ATCC), and cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were screened for pathogens by IDEXX BioAnalytics (Columbia, MO). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 environment with media exchange every 2 days, and confluent cells in T-25 flasks were harvested by EDTA-trypsin, and sub-cultured.

4.2. Animal Procedures

Eight-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (n = 40) were purchased (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) and housed in the Veterinary Medicine Unit at the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center (JBVAMC, Chicago, IL, USA) [

6]. Principles of laboratory animal care were followed, and all procedures were approved by the AALAC accredited Animal Care Committee of the JBVAMC. Mice were fed a standard diet and maintained in groups of three in a cage with routine light–dark cycles. Mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 2.5 x 10

5 B16F10 mouse melanoma cells (ATCC) in 100 μl of normal saline. Treatment by injection of recombinant, human, bioactive ARSB, which was expressed in

E. coli (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or normal saline control injection was started 48 hours following tumor inoculation. Recombinant ARSB was diluted in sterile, normal saline and injected subcutaneously around the tumor with a 25-gauge needle at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg body weight on days 2, 7, and 14 [

6]. Body weight and tumor volume were measured using calipers, and the volume was expressed in cm3 [0.5 × L × W2] (L=long diameter; W=short diameter of the tumor).

4.3. Treatment of A375 Human Melanoma Cells by Exogenous ARSB, siRNAs, and Other Agents

A375 cells were treated by exogenous, bioactive rhARSB (1 ng/ml x 24h; R&D, Biotechne). ARSB, galectin-3, mannose-6 phosphate receptor, and IGFII receptor were silenced by specific siRNA in the A375 cells at 70% confluence using standard procedures and verified siRNA (Oncogene, Thermofisher s7218, s8375). Media were exchanged after 24h, and cell treatments were initiated. Treatments were for 24h, unless indicated otherwise, and included:

cJP (400 μ

m with 2h pre-incubation and total 26h exposure; #1989, R&D Systems, Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN, USA), a cell-permeable c-Jun mimetic peptide, [

36]; JIP-1 (10 μ

m with 2h pre-incubation and total 26h exposure; #1565, Tocris, Bio-Techne), an inhibitor of activated JNK based on interacting protein-1 [

37]; RGFP966 (5 µM, SelleckChem, Houston, TX, USA), an HDAC3 inhibitor; PHPS1 (phenylhydrazonopyrazolone sulfonate or PTPN11, 30 μM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), a chemical inhibitor of SHP2, the tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11; JQ1 (10 µM, MedChem Express, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA), a thienotriazolodiazepine and a potent inhibitor of the BET family of bromodomain proteins [

38]; and methyl β-D-xylopyranoside (1 mM, #M5878, Sigma-Aldrich).

4.4. Treated and Control Cells Were Harvested and Frozen at -80°C for Subsequent Analysis

Small interfering (si) RNAs for ARSB (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), galectin-3 (Qiagen), mannose-6-phosphate receptor (#s8375. Thermofisher) and IGF2R (#s7218, Thermofisher) were validated by QRT-PCR to confirm effective inhibition. The siRNA sequences for ARSB (NM_000046) silencing were: sense 5′- GGGUAUGGUCUCUAGGCA - 3′ and antisense: 5′- UUGCCUAGAGACCAUACCC - 3′. The sequence of the DNA template for human galectin-3 silencing (Hs_ LGALS3_9) was: 5΄ - ATGATGTTGCCTTCCACTTTA - 3′. A375 cells and normal melanocytes were grown to ~60% confluence, then silenced by adding 0.6 μl of 20 μM siRNA (150 ng), mixed with 100 μl of serum-free medium and 12 μl of HiPerfect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen).

4.5. Immunohistochemistry of PD-L1 in A375 Cells

A-375 human melanoma cells were plated in compartment slides and grown to 70–80 % confluence. Cells were treated with ARSB siRNA (Qiagen) or control siRNA (Qiagen) for 24 h or by recombinant human ARSB (1 ng/ml x 24 h). Preparations were then fixed for 2 h with 2 % paraformaldehyde and washed in 1×-PBS containing 1 mM calcium chloride (pH 7.4) for 5 min. Cells were then incubated with 5 % normal goat serum (#501972, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Hanover Park, IL) for blocking and permeabilized with 0.08 % saponin in 1×-PBS/Ca++/saponin. Slides were incubated overnight with PD-L1 antibody (#13684, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) at 4 °C, washed four times in 1×-PBS/Ca++/saponin, and then stained with secondary antibody rabbit anti-mouse FITC IgG (1:100, ab8517, Abcam) for 1 h. Slides were washed four times in 1×-PBS/Ca++/saponin and coverslipped using ProLong™ Gold anti-fade reagent with DAPI (P36941, Invitrogen) for nuclear staining. The fluorochromes were scanned using EVOS M5000 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 20x. The captured TIFF images were exported for analysis and reproduction.

4.6. Arylsulfatase B (ARSB) Activity Assay

ARSB measurements were performed using a fluorometric assay, following a standard protocol with 20 μl of homogenate and 80 μl of assay buffer (0.05 M Na acetate buffer with 20 mM barium sulfate pH 5.6 at 37°C) with 100 μl of substrate (5mM 4-methylumbelliferyl sulfate in fresh assay buffer) in a black microplate, as previously reported [

11].

4.7. Measurement of Total Sulfated Glycosaminoglycans (sGAG) and Chondroitin-4-sulfate

Total sulfated glycosaminoglycans (sGAG) were measured in the cell extracts by sulfated GAG assay (Blyscan

™, Biocolor Ltd, Newtownabbey, Northern Ireland), as previously described [

2]. Chondroitin sulfate (CS) or chondroitin 4-sulfate (C4S) in the samples was determined following immunoprecipitation by dynabeads (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) coated with a total CS antibody (CS-56, Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) or C4S antibody (LY111, Amsbio, Cambridge, MA, USA). Beads were mixed with samples and incubated, and the immunoprecipitated CS molecules were eluted and subjected to the Blyscan sulfated GAG assay, as above.

4.8. Total Sulfotransferase Activity

Total Sulfotransferase activity was determined using the Universal Sulfotransferase Activity kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The activity results were normalized using the total cellular protein and expressed as percentage of the control value.

4.9. ELISAs for Galectin-3, phospho-(Thr183/Tyr185)-JNK, PD-L1

Galectin-3 in the cell lysates was determined by a sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems) for human galectin-3. The wells of a microtiter plate were coated with specific anti-galectin-3 monoclonal antibody, and nonspecific sites were blocked by a blocking buffer with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Sample galectin-3 captured into the microtiter wells was detected by biotin-conjugated secondary galectin-3 antibody and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Hydrogen peroxide-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) chromogenic substrate was used to develop the color, and color intensity was measured at 450 nm in an ELISA plate reader (FLUOstar, BMG Labtech, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The galectin-3 concentrations were extrapolated from a standard curve, and sample values were normalized using total protein content. Galectin-3 in mouse tumor tissues was determined by a similar mouse sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Galectin-3 was also measured following immunoprecipitation of mouse tumor treated and control tissue lysates with the C4S antibody. Chondroitin 4-sulfate was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates, as previously described, and the immunoprecipitate was eluted with dye-free elution buffer and subjected to mouse galectin-3 ELISA.

Cell extracts were prepared from both treated and control cells in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; 9803S). Tumor tissues from treated and untreated animals were homogenized for the measurement of phospho-(Thr183/Tyr185)-JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1). Phospho-JNK was measured in cell and tissue samples using a DuoSet sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Samples and standards were added to the wells of the microtiter plate precoated with a capture antibody to human JNK. Phospho-JNK in the lysates was captured by the coated antibody on the plate and detected with biotinylated antibody to phospho-JNK. Streptavidin-HRP and hydrogen peroxide/TMB substrate were used to develop color which was read at 450 nm in a plate reader (FLUOstar). Phospho-JNK concentrations in the samples were extrapolated from a curve derived using known standards and expressed as % control.

Cell extracts were prepared from both treated and untreated control cells in cell lysis buffer. Malignant tumor issues from treated and untreated mice were homogenized. PD-L1 was measured in cell and tissue samples using a DuoSet sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Samples and standards were added to the wells of the microtiter plate precoated with a capture antibody to human/mouse PD-L1. PD-L1 in the lysates was captured by the coated antibody on the plate and detected with biotinylated antibody to PD-L1. Streptavidin-HRP and hydrogen peroxide/TMB substrate were used to develop color proportional to the bound HRP activity. The reaction was stopped, and the optical density of the color was read at 450 nm in a plate reader (FLUOstar). PD-L1 concentrations in the samples were extrapolated from a curve derived using known standards. PD-L1 was also measured by ELISA (Abcam ab278124) following immunoprecipitation with chondroitin sulfate antibody (CS-56, Abcam), which reacts with C4S and chondroitin 6-sulfate.

4.10. Oligonucleotide-based ELISA to Detect Nuclear c-Jun

Oligonucleotide binding assay (TransAM Kit, Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) was used to detect nuclear c-Jun in the rhARSB-treated and control mouse melanoma tissue, in A375 melanoma cells and in normal melanocyte cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared using a nuclear extract preparation kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and were added to the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate, pre-coated with the AP-1 consensus oligonucleotide sequence (5′-TGAGTCA-3′). The bound c-Jun was recognized by a specific c-Jun primary antibody and finally detected by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Color was developed, using hydrogen peroxide/TMB substrate, and was proportional to the activity of the bound HRP. The reaction was stopped by acid stop solution, and the optical density of the color was read at 450 nm in a plate reader (FLUOstar). Sample values were normalized by total cell protein and expressed as percent of untreated control.

4.11. HDAC3 Activity and Expression

Histone Deacetylase (HDAC)3 in the tissue and cell samples was determined following immunoprecipitation with a specific HDAC3 antibody (Rabbit mAb #85057, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA 01923). Dynabeads (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) were coated with specific HDAC3 (D201K) antibody, and beads were mixed with samples, incubated, and immunoprecipitated. Immunoprecipitated HDAC3 molecules were eluted and subjected to HDAC Activity Assay (ab156064, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Assay buffer and substrate peptide were added to the wells of a black microtiter plate. Reactions were initiated by adding 5 μl buffer for the no enzyme control assay or the enzyme sample to each well, mixed thoroughly, and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature (RT). 20 μL of stop solution were added to each well of the microtiter plate and mixed thoroughly, before adding 5 μL of developer to each well and mixed thoroughly. Following incubation for 20 min at RT, fluorescence intensity was read at Ex/Em = 350 – 380 nm / 440 – 460 nm. HDAC3 activity was expressed as % control.

4.12. mRNA Expression of HDAC3 and PDL1

Total RNA was prepared from treated and control cells using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Equal amounts of purified RNAs from the control and treated cells were reverse-transcribed and amplified using Brilliant SYBR Green QRT-PCR Master Mix (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). Human β-actin was used as an internal control. QRT-PCR was performed using the following specific primers-

PDL1 human (NM_014143) forward: 5′-TTTACTGTCACGGTTCCCAAG-3′ and reverse: 5′-GCTGAACCTTCAGGTCTTCCT-3′;

PDL1 mouse (NM_021893) forward: 5′-AGTTTGTGGCAGGAGAGGAG-3′ and reverse: 5′-CTGGTTGATTTTGCGGTATG-3′.

HDAC3 human (NM_003880) forward: 5′-GAGTTCTGCTCGCGTTACACAG-3′ and reverse: 5′-CGTTGACATAGCAGACAGAG-3′;

HDAC3 mouse (NM_010411) forward: 5′-AACCTCATCGCCTGGCATTGAC-3′ and reverse: 5′-GTAGTCCTCAGAGAAGCGG-3′;

4.13. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay for Histone 3-Acetylation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed using the Acetyl-Histone H3 Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay Kit (#17–245, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). A375 melanoma cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. This was followed by shearing of chromatin by sonication on ice to obtain DNA lengths between 200 and 1000 base pairs. Soluble chromatin fragments of 200 to 1000 bp in length were incubated with 5 μg of anti-acetyl-histone H3 antibodies at 4°C overnight. Normal rabbit IgG was used as a negative control for validating the ChIP assay. Protein–DNA complexes were precipitated by protein A/G-coupled magnetic beads. DNA was purified from the immunoprecipitated complexes by reversal of cross-linking and followed by proteinase K treatment. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green QRT-PCR master mix (BIORAD). Two sets of ChIP primers covering 1800 bp upstream of the human PD-L1 gene start codon and designed by NCBI-Blast software were: primer 1 (− 1178 bp to − 1117 bp), forward 5′-GCT GGG CCC AAA CCC TAT T−3′ and reverse 5′-TTT GGC AGG AGC ATG GAG TT-3′; primer 2 (− 455 bp to − 356 bp), forward 5′-ATG GGT CTG CTG CTG ACT TT-3′ and reverse 5′-GGC GTC CCC CTT TCTGAT AA-3′ [

25]. The ChIP qPCR result was calculated using the ΔΔCt method. Briefly, each ChIP fractions’ Ct value was normalized to the input DNA fraction and expressed as % Input. Band intensity was compared among the IgG, treated, and control samples on a 1.5% agarose gel, and densitometric analysis was carried out using ImageJ software.

4.14. Statistical Analysis

Data presented are the mean ± SD of at least six independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-tests, two-tailed, corrected for unequal variance using Microsoft Excel or Prizm 10 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA), unless stated otherwise. In the figures, **** represents p<0.0001, *** represents p≤0.001, ** represents p≤ 0.01, and * is for p≤ 0.05. The top of the bar is the mean value and horizontal bars indicate one standard deviation. Each dot represents an independent experiment.

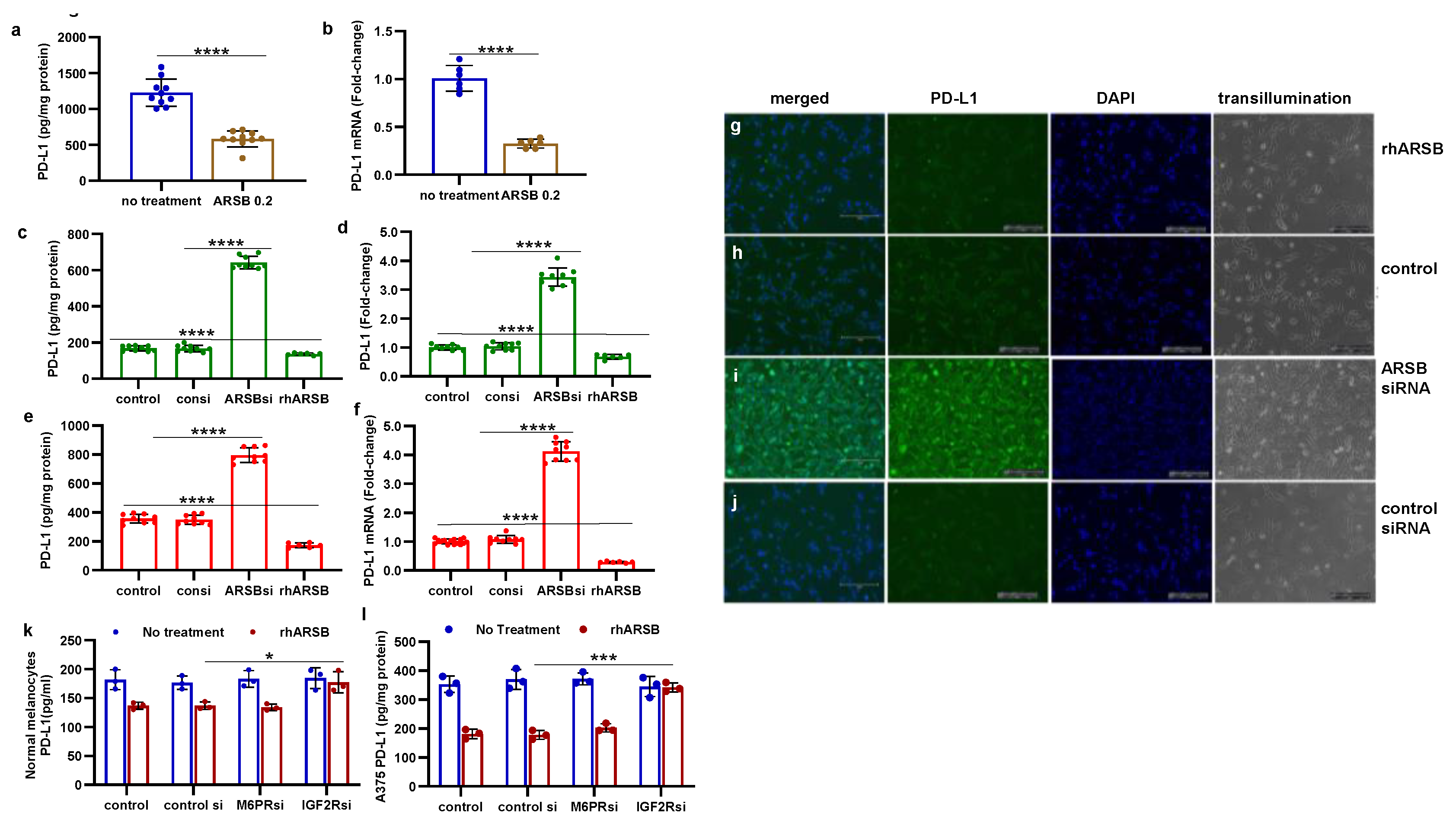

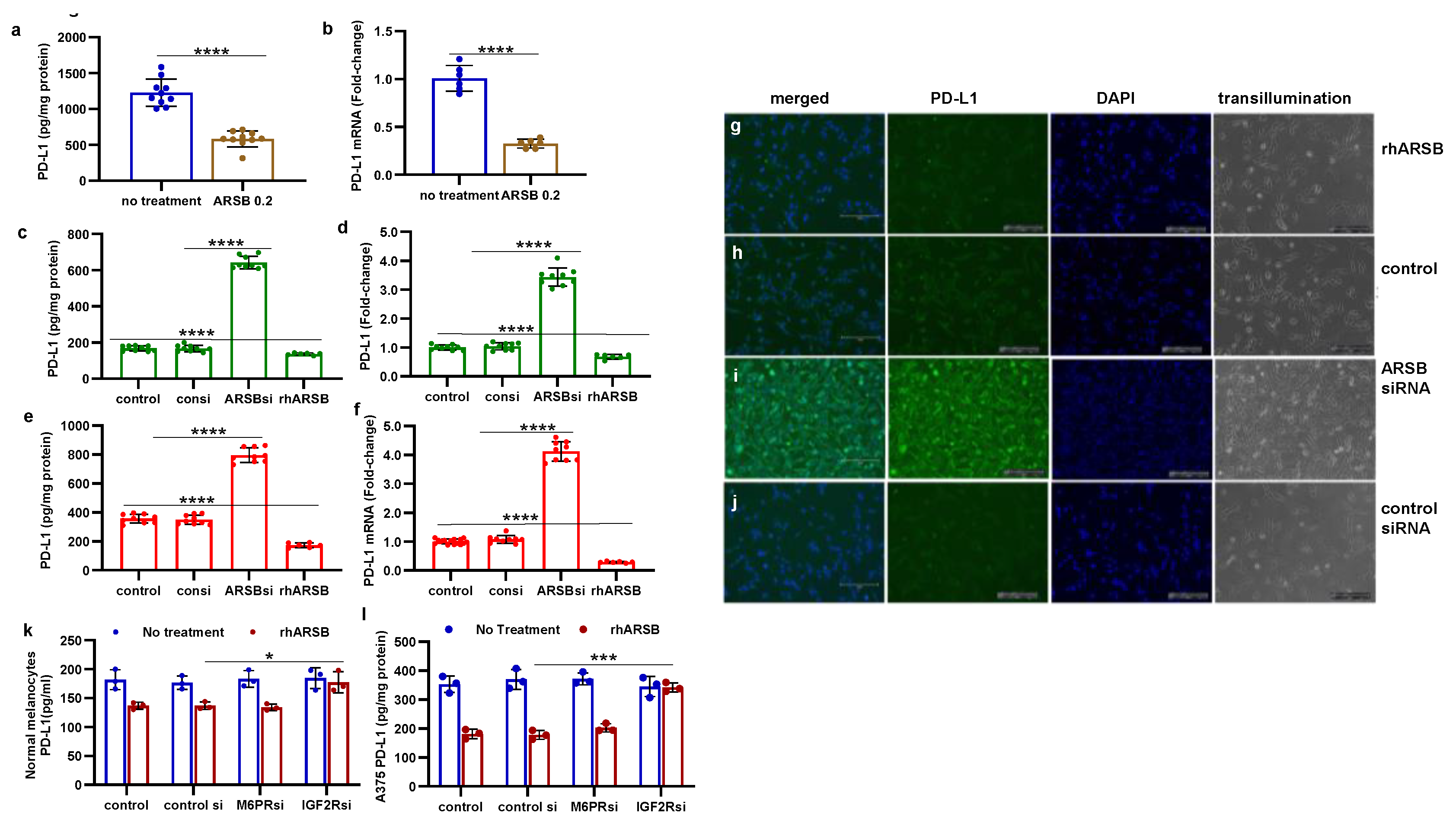

Figure 1.

PD-L1 expression and protein in B16F10 subcutaneous melanomas, normal melanocytes, and A375 melanoma cells following ARSB silencing and exposure to exogenous ARSB. A,B. In the mouse melanomas, PD-L1 protein (n=9) and mRNA expression (n=6) are reduced following treatment with exogenous, bioactive ARSB (p<0.0001). C,D. In normal human melanocytes, ARSB silencing increases protein and mRNA expression of PD-L1 (p<0.0001, n=9). E,F. Similarly, in the malignant A375 cells, PD-L1 protein and mRNA are increased by ARSB silencing and reduced by rhARSB (p<0.0001, n=9). The baseline PD-L1 value is greater in the malignant than in the normal cells. G-J. Immunohistochemistry of cultured A375 cells stained for PD-L1 demonstrates decline following rhARSB (G) and marked increase following ARSB siRNA (I), compared to control (H) and control siRNA (J). K,L. In the normal melanocytes and the A375 cells, silencing of the mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6PR) by siRNA did not block the effect of exogenous ARSB on PD-L1 expression. In contrast, silencing of the calcium-independent insulin growth factor 2 receptor (IGF2R) by siRNA blocked almost completely the rhARSB-induced decline in PD-L1. P-values are <0.0001, determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance and n=>6. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; IGF2R=insulin growth factor 2 receptor; M6PR = mannose-6-phosphate receptor; PD-L1=programmed death ligand-1; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

Figure 1.

PD-L1 expression and protein in B16F10 subcutaneous melanomas, normal melanocytes, and A375 melanoma cells following ARSB silencing and exposure to exogenous ARSB. A,B. In the mouse melanomas, PD-L1 protein (n=9) and mRNA expression (n=6) are reduced following treatment with exogenous, bioactive ARSB (p<0.0001). C,D. In normal human melanocytes, ARSB silencing increases protein and mRNA expression of PD-L1 (p<0.0001, n=9). E,F. Similarly, in the malignant A375 cells, PD-L1 protein and mRNA are increased by ARSB silencing and reduced by rhARSB (p<0.0001, n=9). The baseline PD-L1 value is greater in the malignant than in the normal cells. G-J. Immunohistochemistry of cultured A375 cells stained for PD-L1 demonstrates decline following rhARSB (G) and marked increase following ARSB siRNA (I), compared to control (H) and control siRNA (J). K,L. In the normal melanocytes and the A375 cells, silencing of the mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6PR) by siRNA did not block the effect of exogenous ARSB on PD-L1 expression. In contrast, silencing of the calcium-independent insulin growth factor 2 receptor (IGF2R) by siRNA blocked almost completely the rhARSB-induced decline in PD-L1. P-values are <0.0001, determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance and n=>6. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; IGF2R=insulin growth factor 2 receptor; M6PR = mannose-6-phosphate receptor; PD-L1=programmed death ligand-1; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

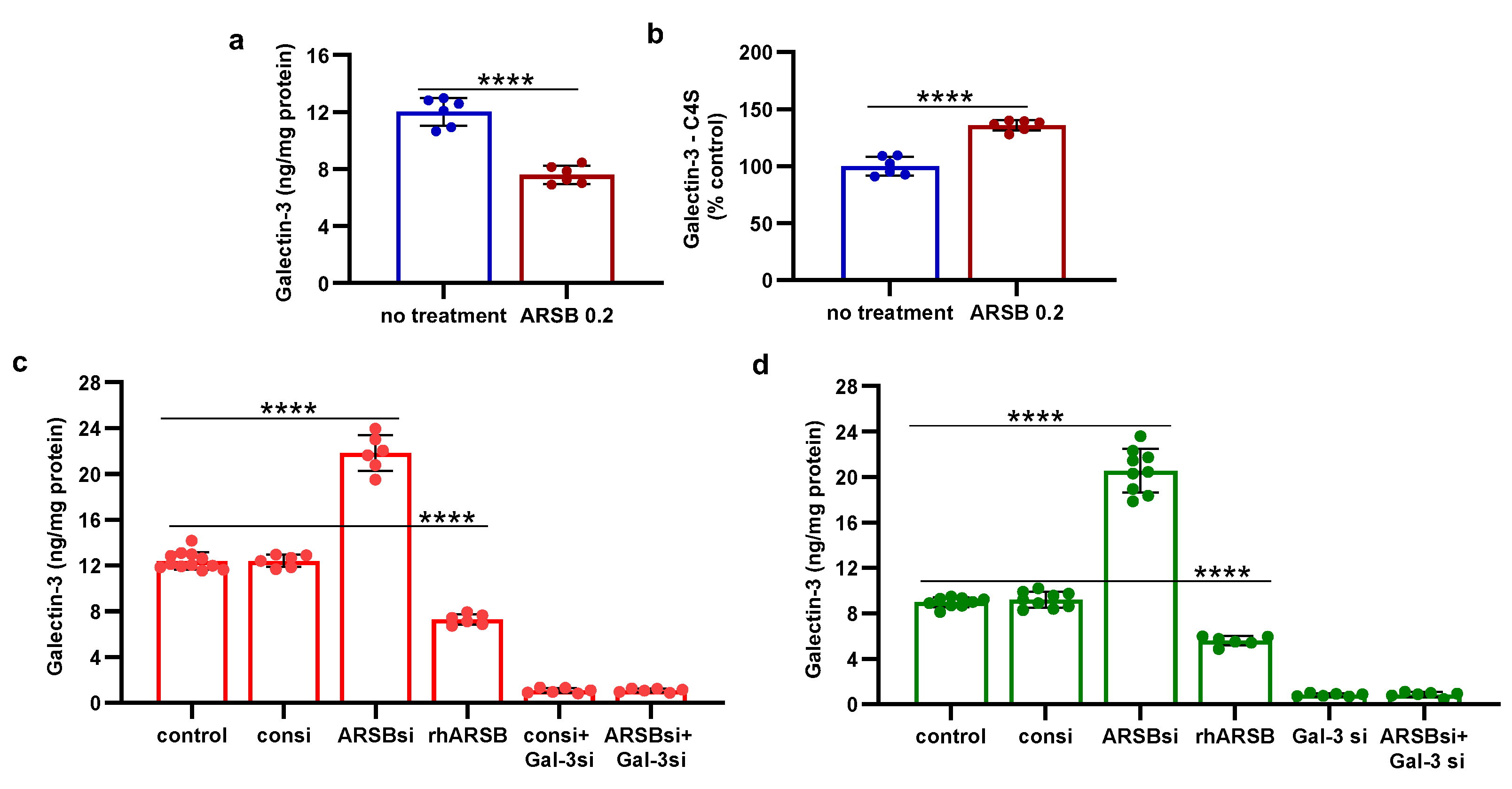

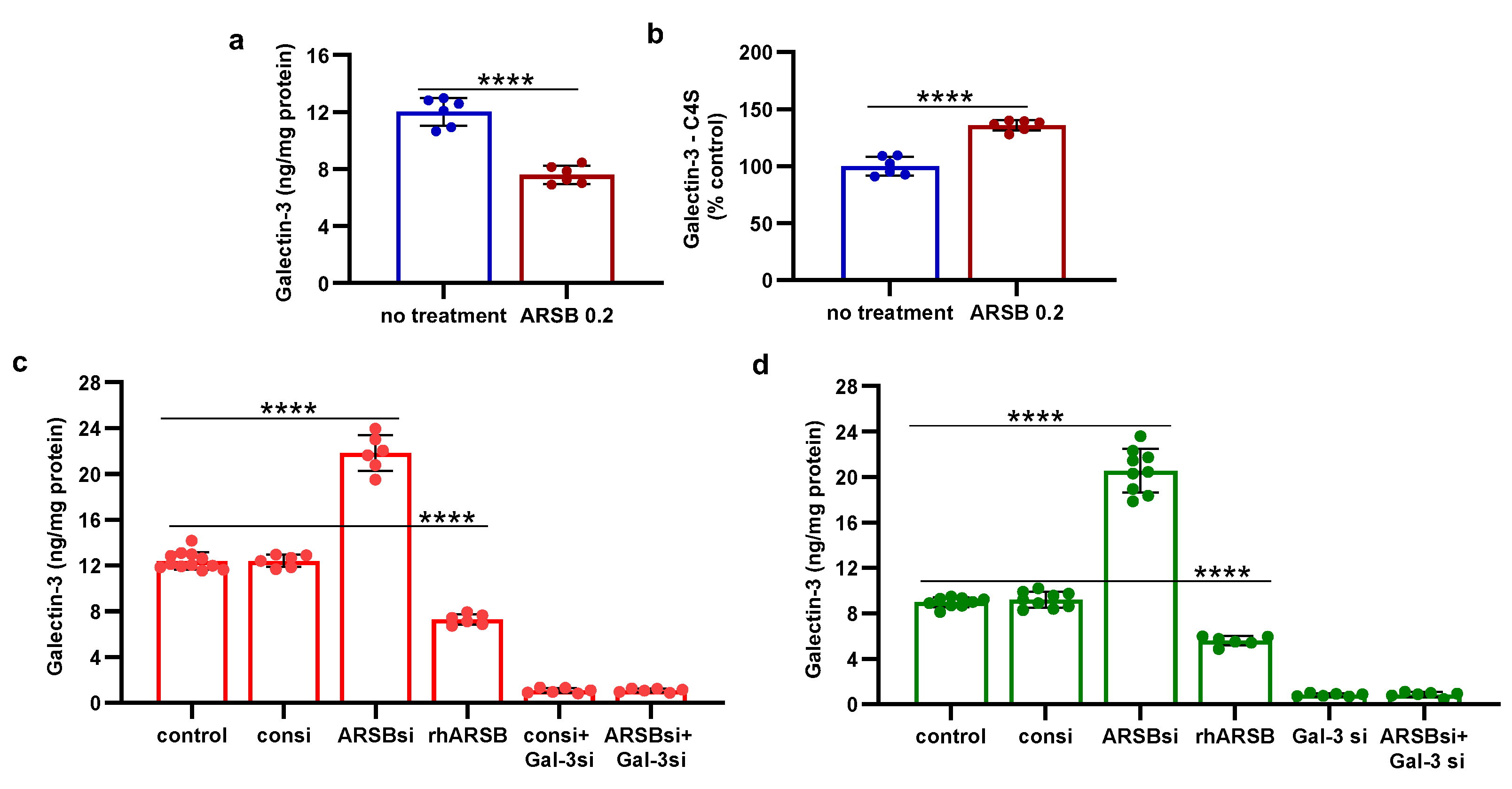

Figure 2.

Inverse effects of silencing ARSB and rhARSB on galectin-3 due to altered binding with chondroitin 4-sulfate. A. In the mouse melanoma tissue, treatment by recombinant ARSB reduced the free galectin-3, as measured by ELISA (p<0.0001, n=6). B. The decline in free galectin-3 is attributed to increased binding of galectin-3 with chondroitin 4-sulfate, which was detected following immunoprecipitation of tumor tissue with C4S antibody. C. In the A375 melanoma cells, free galectin-3 increased when ARSB was silenced and declined following exogenous ARSB (p<0.0001), consistent with altered binding with C4S following decline or increase in ARSB activity. Galectin-3 siRNA effectively reduced galectin-3 protein. D. Similarly, in the normal human melanocytes, ARSB siRNA led to increase in free galectin-3 and exogenous ARSB led to decline (p<0.0001). P-values are <0.0001, determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance and n>6 for all determinations. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; gal-3=galectin-3; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

Figure 2.

Inverse effects of silencing ARSB and rhARSB on galectin-3 due to altered binding with chondroitin 4-sulfate. A. In the mouse melanoma tissue, treatment by recombinant ARSB reduced the free galectin-3, as measured by ELISA (p<0.0001, n=6). B. The decline in free galectin-3 is attributed to increased binding of galectin-3 with chondroitin 4-sulfate, which was detected following immunoprecipitation of tumor tissue with C4S antibody. C. In the A375 melanoma cells, free galectin-3 increased when ARSB was silenced and declined following exogenous ARSB (p<0.0001), consistent with altered binding with C4S following decline or increase in ARSB activity. Galectin-3 siRNA effectively reduced galectin-3 protein. D. Similarly, in the normal human melanocytes, ARSB siRNA led to increase in free galectin-3 and exogenous ARSB led to decline (p<0.0001). P-values are <0.0001, determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance and n>6 for all determinations. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; gal-3=galectin-3; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

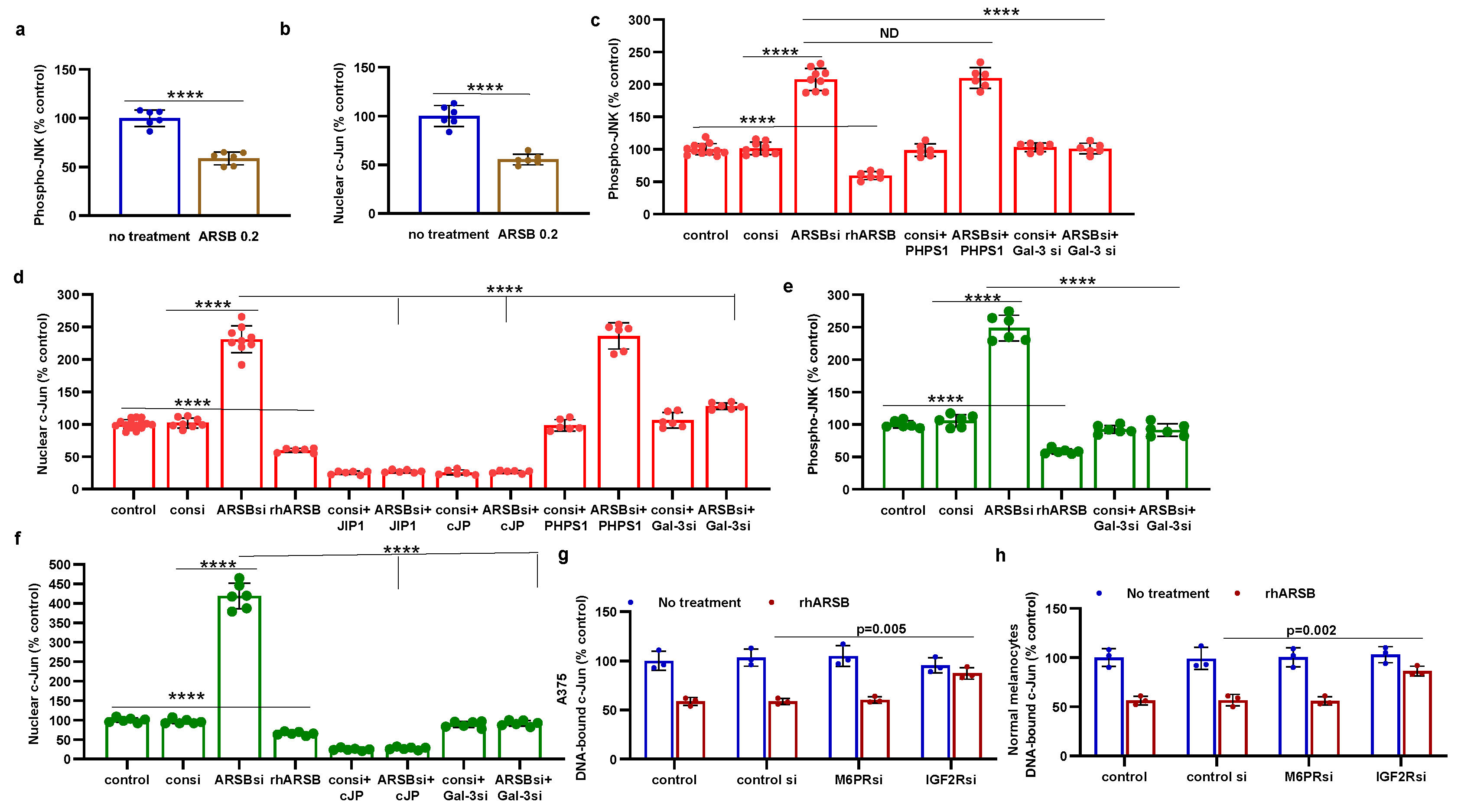

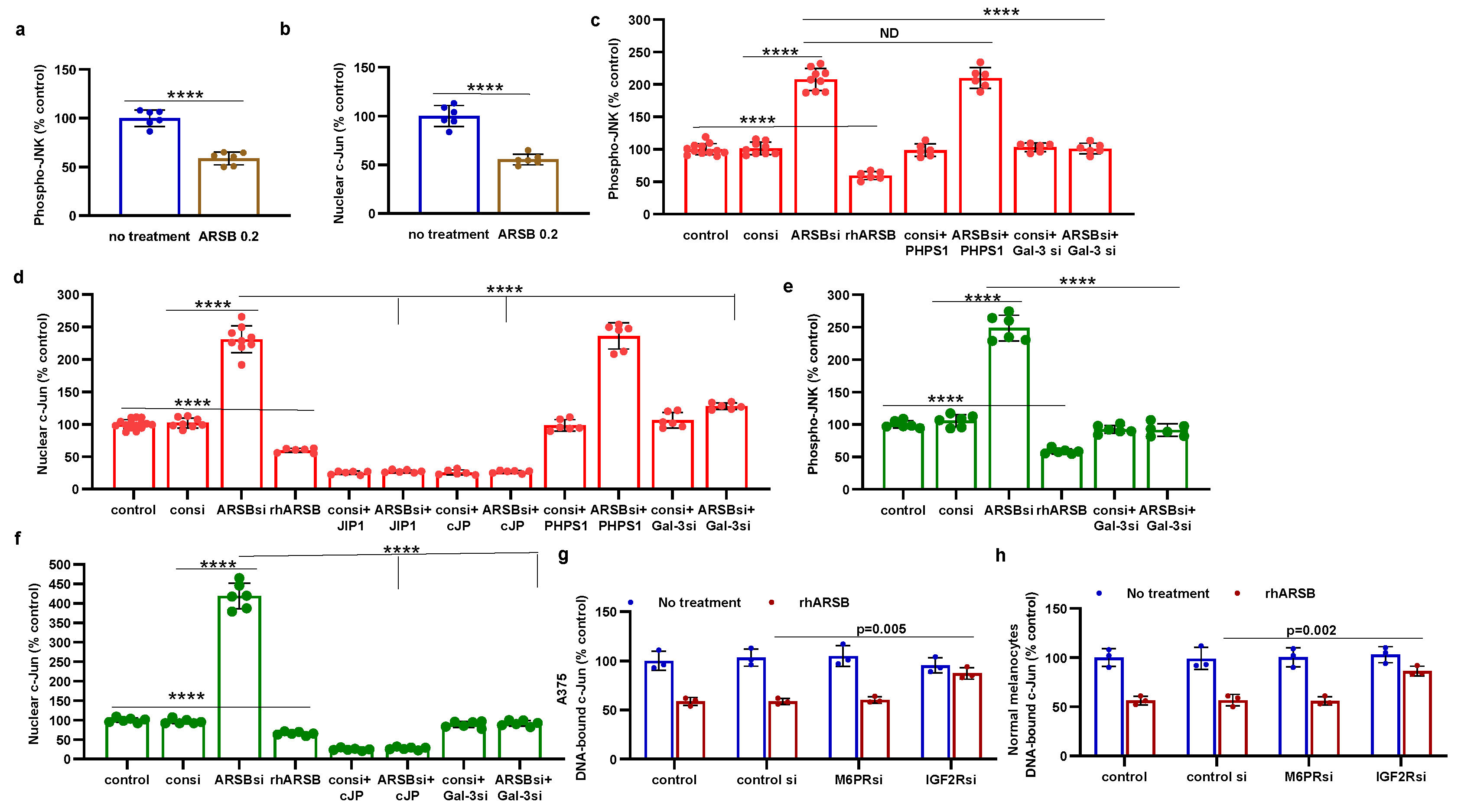

Figure 3.

Inverse effects of ARSB siRNA and rhARSB on phospho-JNK and nuclear c-jun. A,B. In the mouse melanoma tissue, phospho-(Thr183/Tyr185)-JNK and nuclear c-Jun declined following exogenous ARSB (p<0.0001, n=6). C,D. In the A375 cells, ARSB siRNA increased phospho-JNK (p<0.0001, n=9) and nuclear c-Jun (p<0.0001, n=9).. In contrast, rhARSB reduced both phospho-JNK (p<0.0001, n=6) and c-Jun (p<0.0001, n=6). The SHP-2 inhibitor PHPS1 did not reduce the effect of ARSB siRNA. In contrast, galectin-3 siRNA significantly reduced the ARSB si-induced increases. JIP1, a JNK-selective inhibitory peptide, and cJP, a c-Jun mimetic peptide, both completely blocked the increases caused by ARSB siRNA. E,F. Similarly, in the normal melanocytes, phospho-JNK and DNA-bound c-Jun were affected by ARSB siRNA and recombinant ARSB (p<0.0001, n=6). Galectin-3 silencing blocked the effect of ARSB siRNA. G,H. In the A375 cells and the normal melanocytes, the effect of exogenous ARSB on DNA-bound c-Jun was inhibited by the IGF2R siRNA (p=0.005, p=0.002; n=3, n=3), but not by M6PR silencing. P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; gal-3=galectin-3; IGF2R=insulin growth factor 2 receptor; JIP1=JNK-selective inhibitory peptide; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide; JNK=c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1; M6PR = mannose-6-phosphate receptor; PD-L1=programmed death ligand-1; PHPS1=SHP2 inhibitor; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

Figure 3.

Inverse effects of ARSB siRNA and rhARSB on phospho-JNK and nuclear c-jun. A,B. In the mouse melanoma tissue, phospho-(Thr183/Tyr185)-JNK and nuclear c-Jun declined following exogenous ARSB (p<0.0001, n=6). C,D. In the A375 cells, ARSB siRNA increased phospho-JNK (p<0.0001, n=9) and nuclear c-Jun (p<0.0001, n=9).. In contrast, rhARSB reduced both phospho-JNK (p<0.0001, n=6) and c-Jun (p<0.0001, n=6). The SHP-2 inhibitor PHPS1 did not reduce the effect of ARSB siRNA. In contrast, galectin-3 siRNA significantly reduced the ARSB si-induced increases. JIP1, a JNK-selective inhibitory peptide, and cJP, a c-Jun mimetic peptide, both completely blocked the increases caused by ARSB siRNA. E,F. Similarly, in the normal melanocytes, phospho-JNK and DNA-bound c-Jun were affected by ARSB siRNA and recombinant ARSB (p<0.0001, n=6). Galectin-3 silencing blocked the effect of ARSB siRNA. G,H. In the A375 cells and the normal melanocytes, the effect of exogenous ARSB on DNA-bound c-Jun was inhibited by the IGF2R siRNA (p=0.005, p=0.002; n=3, n=3), but not by M6PR silencing. P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; gal-3=galectin-3; IGF2R=insulin growth factor 2 receptor; JIP1=JNK-selective inhibitory peptide; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide; JNK=c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1; M6PR = mannose-6-phosphate receptor; PD-L1=programmed death ligand-1; PHPS1=SHP2 inhibitor; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

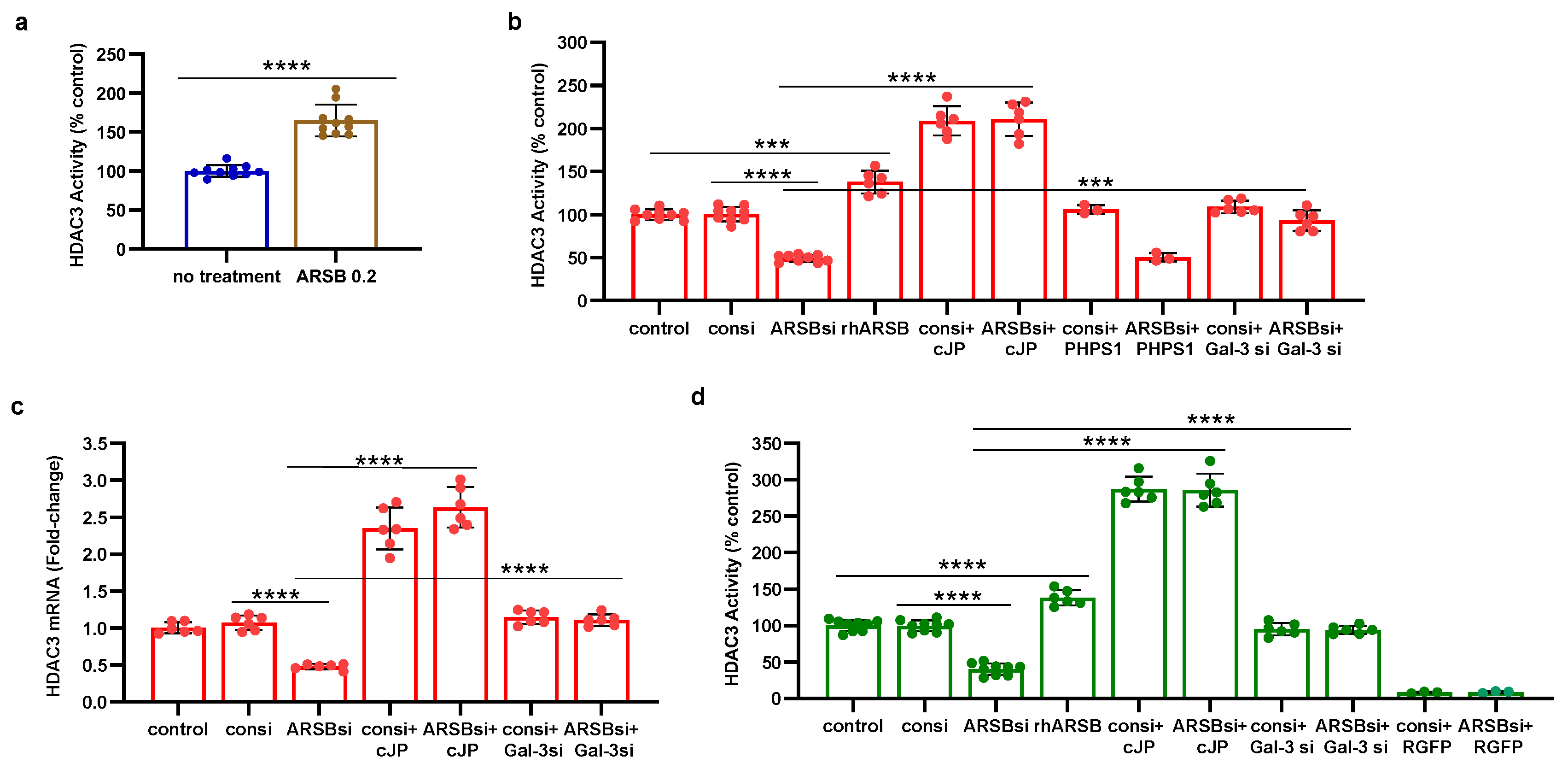

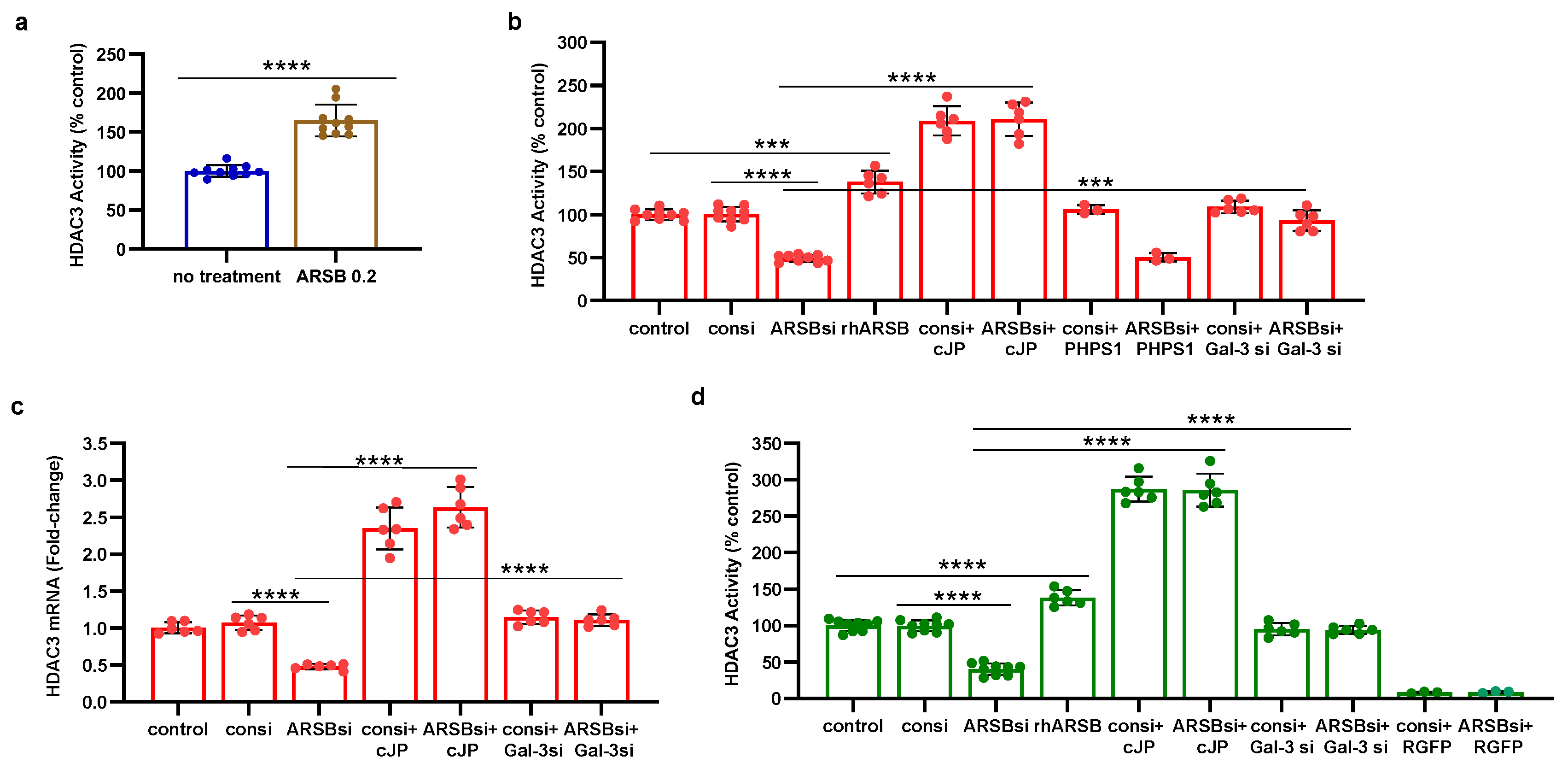

Figure 4.

HDAC3 activity and expression are increased following exogenous ARSB A. In the B16F10 tumors, histone deacetylase (HDAC)3 activity was increased by over 50% following local treatment by exogenous ARSB (0.2 mg/kg x 3 doses) (p<0.001, n=9). B. In the A375 melanoma cells, ARSB silencing reduced (p<0.0001, n=9) and rhARSB increased (p<0.001, n=6) the HDAC3 activity. Treatment by c-Jun mimetic peptide (cJP) markedly increased the HDAC3 activity to 200% of the control level. The SHP2 inhibitor PHPS1 did not affect the ARSB siRNA induced decline, but galectin-3 silencing restored the HDAC-3 activity to near baseline (p<0.001, n=6). C. HDAC3 expression was reduced by ARSB siRNA (p<0.0001, n=6) and normalized by galectin-3 silencing (p<0.0001, n=6). HDAC3 mRNA was increased to 2.3 ± 0.3 times baseline following treatment by cJP. D. In the normal human melanocytes, similar effects of ARSB siRNA, cJP, and galectin-3 siRNA are apparentas in the malignant A375 cells (p<0.0001). RGFP699 completely blocked the HDAC3 activity. P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance, and n>6. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; gal-3=galectin-3; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide; RGFP=RGFP966=HDAC3 inhibitor; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

Figure 4.

HDAC3 activity and expression are increased following exogenous ARSB A. In the B16F10 tumors, histone deacetylase (HDAC)3 activity was increased by over 50% following local treatment by exogenous ARSB (0.2 mg/kg x 3 doses) (p<0.001, n=9). B. In the A375 melanoma cells, ARSB silencing reduced (p<0.0001, n=9) and rhARSB increased (p<0.001, n=6) the HDAC3 activity. Treatment by c-Jun mimetic peptide (cJP) markedly increased the HDAC3 activity to 200% of the control level. The SHP2 inhibitor PHPS1 did not affect the ARSB siRNA induced decline, but galectin-3 silencing restored the HDAC-3 activity to near baseline (p<0.001, n=6). C. HDAC3 expression was reduced by ARSB siRNA (p<0.0001, n=6) and normalized by galectin-3 silencing (p<0.0001, n=6). HDAC3 mRNA was increased to 2.3 ± 0.3 times baseline following treatment by cJP. D. In the normal human melanocytes, similar effects of ARSB siRNA, cJP, and galectin-3 siRNA are apparentas in the malignant A375 cells (p<0.0001). RGFP699 completely blocked the HDAC3 activity. P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance, and n>6. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; gal-3=galectin-3; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide; RGFP=RGFP966=HDAC3 inhibitor; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

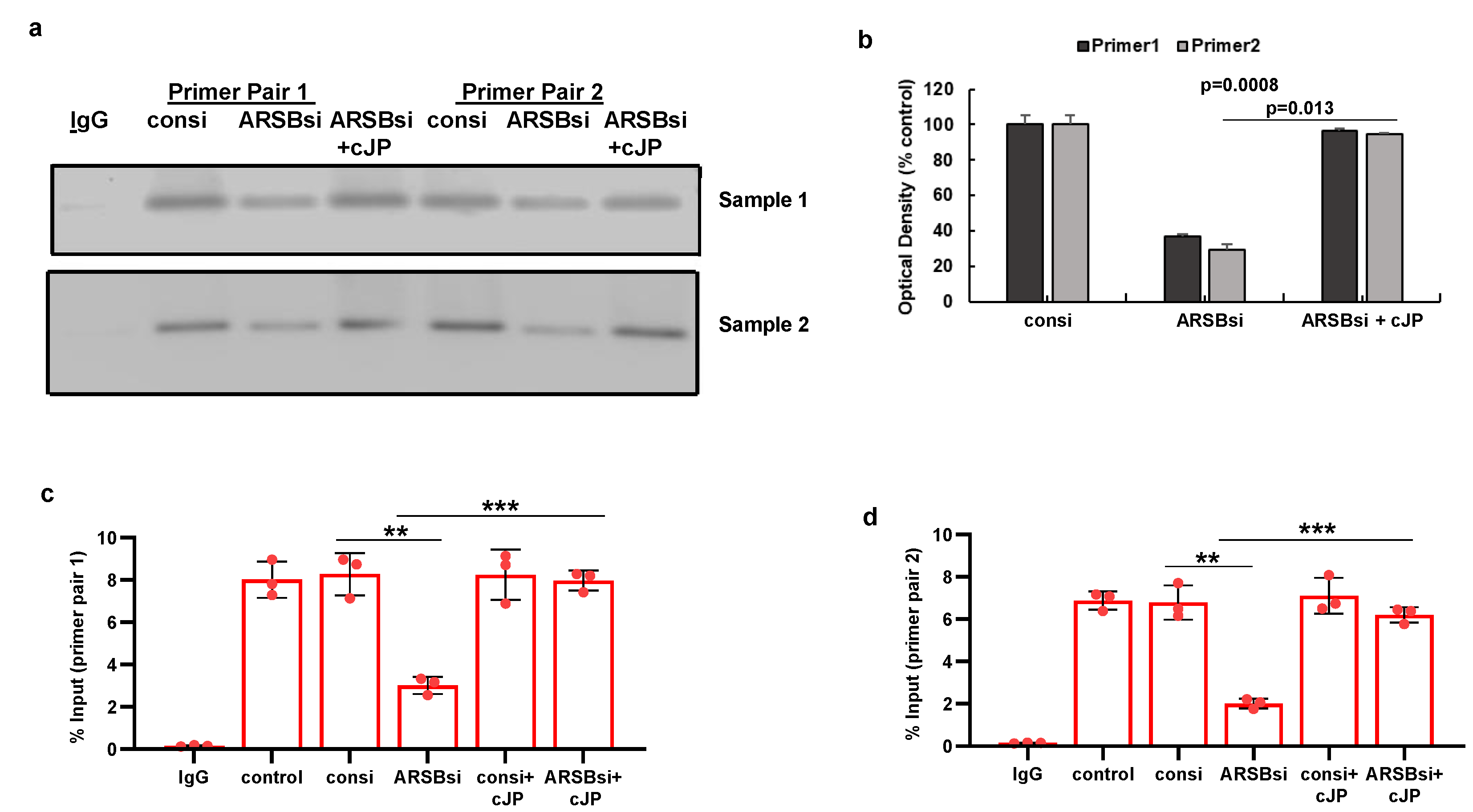

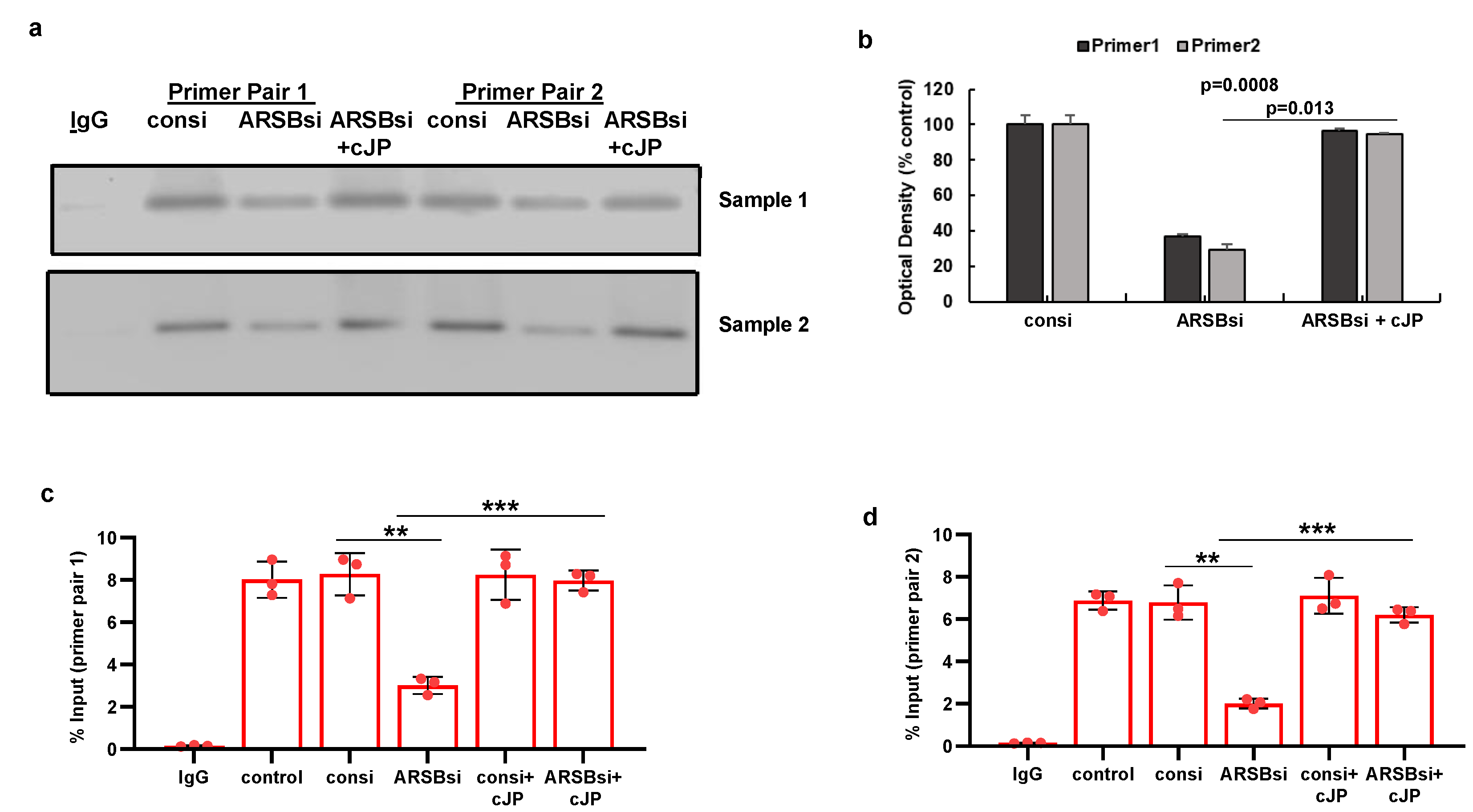

Figure 5.

Histone-3 acetylation at PD-L1 promoter follows ARSB silencing in A375 cells. A. A375 melanoma cells, including cells treated by ARSB siRNA, control siRNA, ARSB siRNA + cJP, and IgG negative control, were fixed with 1% formaldehyde, chromatin was sheared, and soluble chromatin fragments were incubated with acetyl-H3 antibodies. Protein–DNA complexes were precipitated, DNA was immunoprecipitated by reversal of cross-linking, and QRT-PCR was performed using two sets of primers upstream of the PD-L1 start codon. Band intensity is diminished when ARSB was silenced, consistent with open chromatin and increased expression of PD-L1. Treatment of the cells ARSB siRNA and cJP normalized the band intensity. B. Densitometry of the bands quantifies the observed differences in intensity using two treated cell samples. C,D. Primer pair 1 yields slightly greater % DNA input than primer pair 2. Both show similar effects of ARSB siRNA and ARSB siRNA + cJP. P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide].

Figure 5.

Histone-3 acetylation at PD-L1 promoter follows ARSB silencing in A375 cells. A. A375 melanoma cells, including cells treated by ARSB siRNA, control siRNA, ARSB siRNA + cJP, and IgG negative control, were fixed with 1% formaldehyde, chromatin was sheared, and soluble chromatin fragments were incubated with acetyl-H3 antibodies. Protein–DNA complexes were precipitated, DNA was immunoprecipitated by reversal of cross-linking, and QRT-PCR was performed using two sets of primers upstream of the PD-L1 start codon. Band intensity is diminished when ARSB was silenced, consistent with open chromatin and increased expression of PD-L1. Treatment of the cells ARSB siRNA and cJP normalized the band intensity. B. Densitometry of the bands quantifies the observed differences in intensity using two treated cell samples. C,D. Primer pair 1 yields slightly greater % DNA input than primer pair 2. Both show similar effects of ARSB siRNA and ARSB siRNA + cJP. P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide].

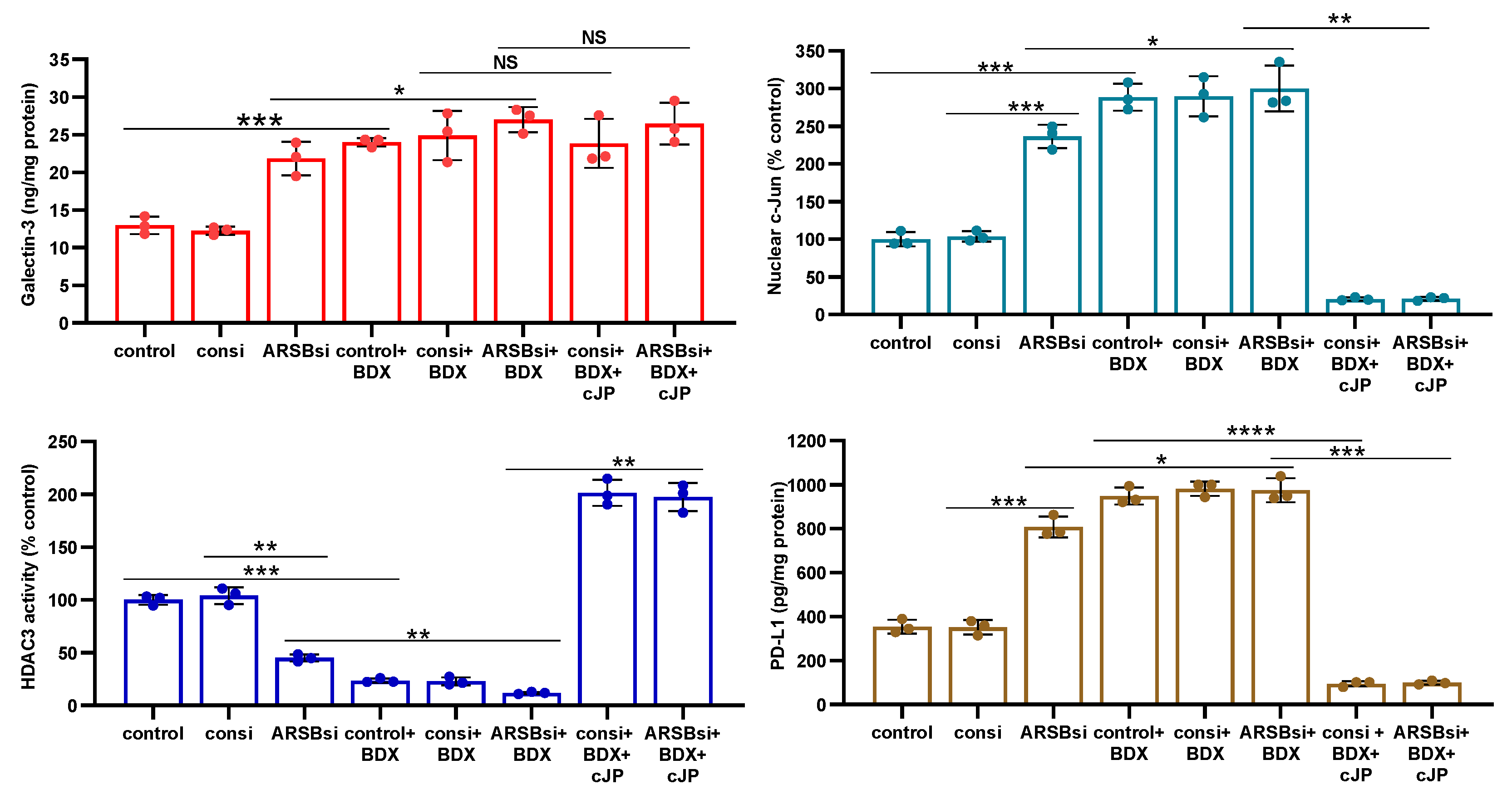

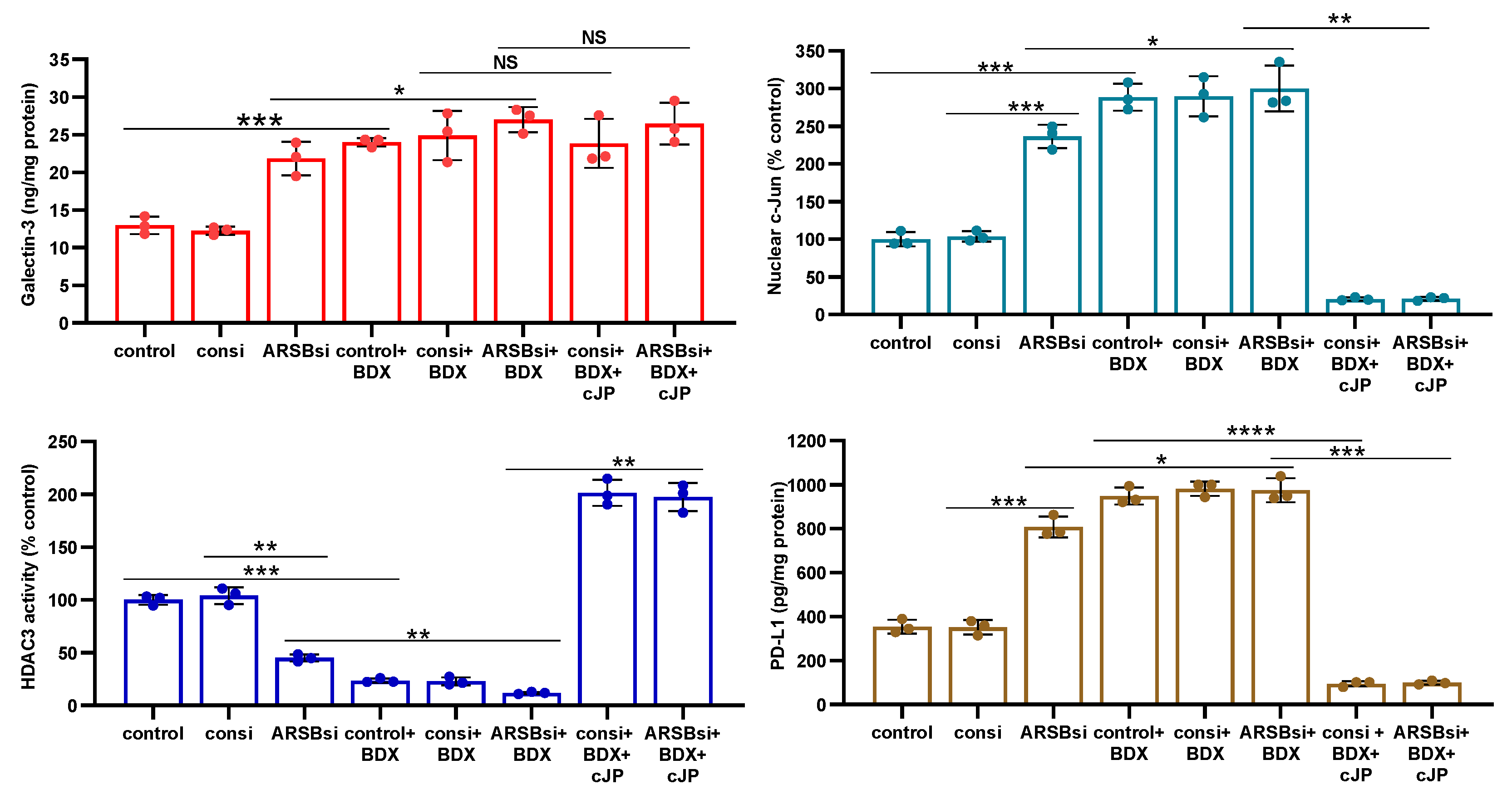

Figure 6.

Impact of methyl-β-D-xylopyranoside (BDX) on mediators of PD-L1 expression. A. Methyl-β-D-xylopyranoside (BDX), an inhibitor of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan biosynthesis, increases free galectin-3 in the A375 cells (p<0.001, n=3). The combination of ARSB siRNA and BDX has slightly greater effect than ARSB siRNA alone (p<0.05, n=3). B. Nuclear c-Jun is increased by BDX (p<0.001, n=3) and ARSB siRNA (p<0.001, n=3). cJP inhibits the effects of BDX and ARSB siRNA. C. HDAC3 activity is reduced by both ARSB siRNA (p=0.002, n=3) and BDX (p=0.0002, n=3), and further reduced by their combination (p=0.002, p=0.003). These effects are reversed by cJP. D. PD-L1 expression is increased by both ARSB siRNA and BDX, and these increases are inhibited by cJP. P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; BDX=methyl-β-D-xylopyranoside; consi=control siRNA; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide; HDAC=histone deacetylase; PD-L1=programmed death ligand-1; PHPS1=SHP2 inhibitor; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose].

Figure 6.

Impact of methyl-β-D-xylopyranoside (BDX) on mediators of PD-L1 expression. A. Methyl-β-D-xylopyranoside (BDX), an inhibitor of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan biosynthesis, increases free galectin-3 in the A375 cells (p<0.001, n=3). The combination of ARSB siRNA and BDX has slightly greater effect than ARSB siRNA alone (p<0.05, n=3). B. Nuclear c-Jun is increased by BDX (p<0.001, n=3) and ARSB siRNA (p<0.001, n=3). cJP inhibits the effects of BDX and ARSB siRNA. C. HDAC3 activity is reduced by both ARSB siRNA (p=0.002, n=3) and BDX (p=0.0002, n=3), and further reduced by their combination (p=0.002, p=0.003). These effects are reversed by cJP. D. PD-L1 expression is increased by both ARSB siRNA and BDX, and these increases are inhibited by cJP. P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; BDX=methyl-β-D-xylopyranoside; consi=control siRNA; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide; HDAC=histone deacetylase; PD-L1=programmed death ligand-1; PHPS1=SHP2 inhibitor; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose].

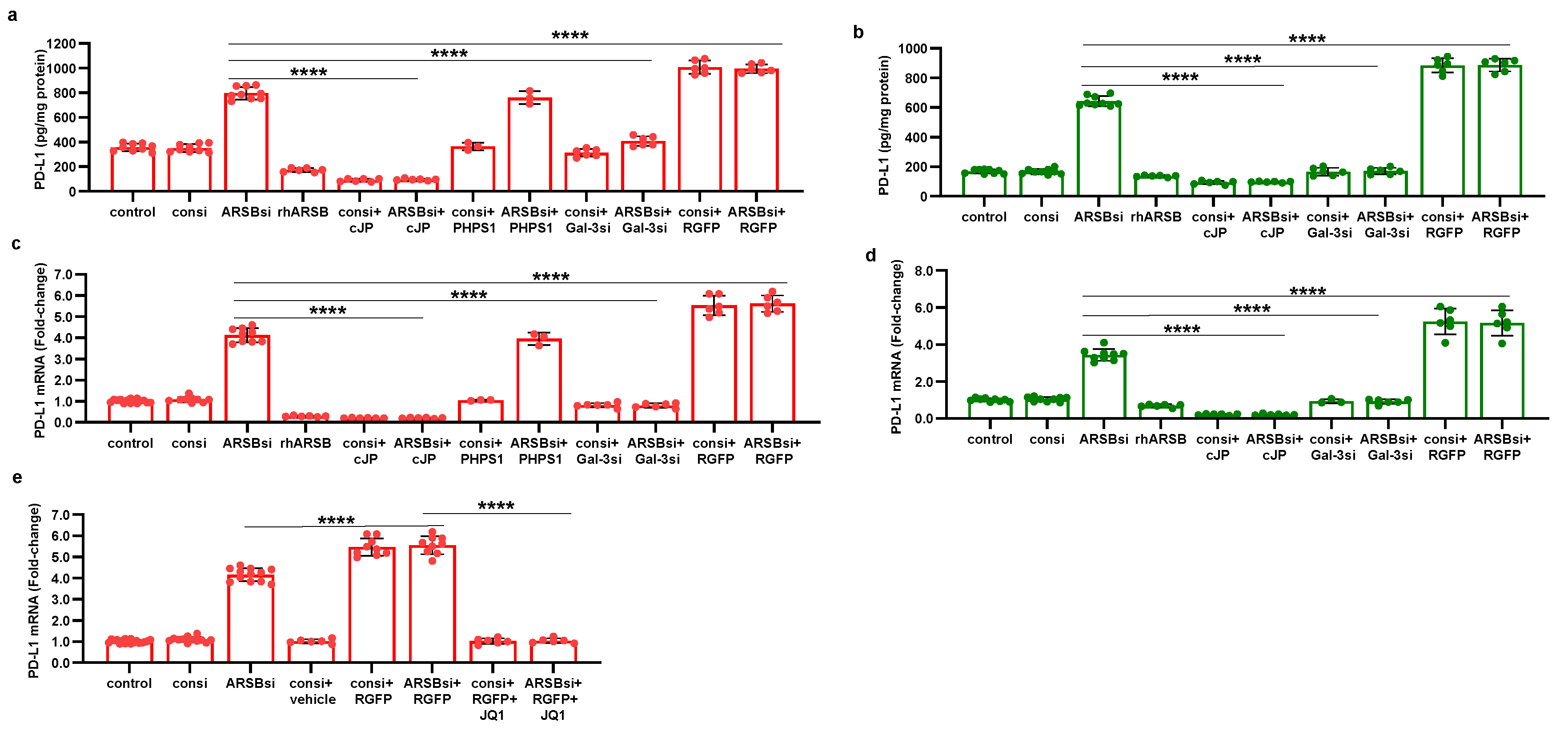

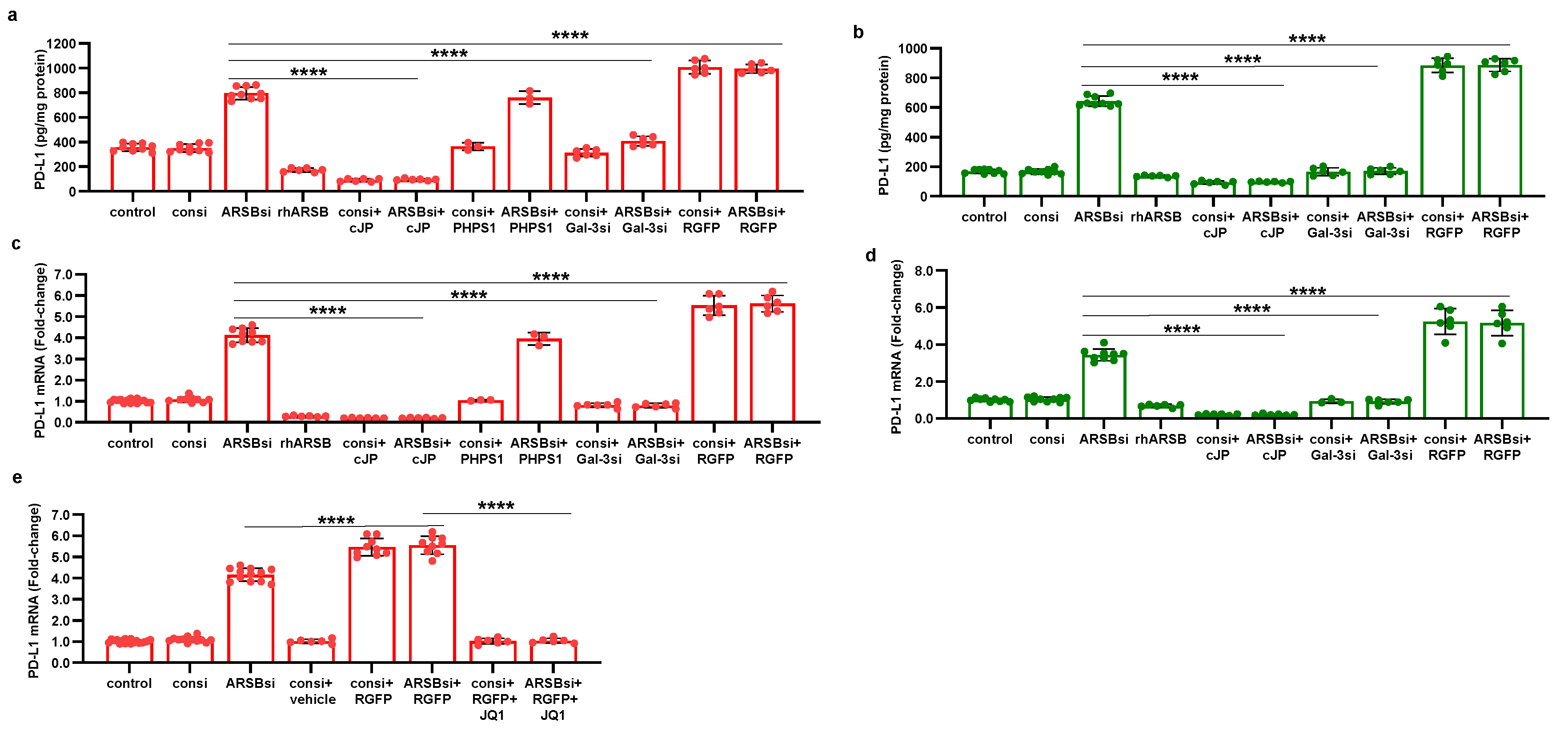

Figure 7.

Effects of inhibition of c-jun, galectin-3, and HDAC3 on ARSB-mediated changes in PD-L1 expression in A375 melanoma cells and normal melanocytes. A. In the A375 cells, PD-L1 protein is markedly increased by ARSB siRNA, and this increase is inhibited by cJP and galectin-3 siRNA. PHPS1 does not affect the PD-L1 expression. The HDAC3 inhibitor, RGFP966, further increases the ARSB siRNA-induced increase in PD-L1. B. In normal melanocytes, similar effects of ARSB siRNA, cJP, galectin-3 siRNA, and RGFP are observed. The total production of PD-L1 is less than in the A375 cells (642 ± 34 pg/mg protein vs. 796.± 50 pg/mg protein; p<0.0001, n=9). C,D. Similar effects are observed in PD-L1 mRNA expression in the A375 malignant cells and the normal melanocytes (p<0.0001). Galectin-3 siRNA inhibits the effect of ARSB silencing, consistent with dependence on galectin-3 for the observed effects. E. JQ1, the inhibitor of the BET family of bromodomain proteins, blocks the effects of ARSB siRNA and RGFP on PD-L1 expression (p<0.0001). P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; gal-3=galectin-3; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide; JQ1=inhibitor of the BET family of bromodomain proteins; PD-L1=programmed death ligand-1; PHPS1=SHP2 inhibitor; RGFP=RGFP966=HDAC3 inhibitor; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

Figure 7.

Effects of inhibition of c-jun, galectin-3, and HDAC3 on ARSB-mediated changes in PD-L1 expression in A375 melanoma cells and normal melanocytes. A. In the A375 cells, PD-L1 protein is markedly increased by ARSB siRNA, and this increase is inhibited by cJP and galectin-3 siRNA. PHPS1 does not affect the PD-L1 expression. The HDAC3 inhibitor, RGFP966, further increases the ARSB siRNA-induced increase in PD-L1. B. In normal melanocytes, similar effects of ARSB siRNA, cJP, galectin-3 siRNA, and RGFP are observed. The total production of PD-L1 is less than in the A375 cells (642 ± 34 pg/mg protein vs. 796.± 50 pg/mg protein; p<0.0001, n=9). C,D. Similar effects are observed in PD-L1 mRNA expression in the A375 malignant cells and the normal melanocytes (p<0.0001). Galectin-3 siRNA inhibits the effect of ARSB silencing, consistent with dependence on galectin-3 for the observed effects. E. JQ1, the inhibitor of the BET family of bromodomain proteins, blocks the effects of ARSB siRNA and RGFP on PD-L1 expression (p<0.0001). P-values are determined by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, with unequal variance. [ARSB=arylsulfatase B=N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase; consi=control siRNA; gal-3=galectin-3; cJP=c-Jun mimetic peptide; JQ1=inhibitor of the BET family of bromodomain proteins; PD-L1=programmed death ligand-1; PHPS1=SHP2 inhibitor; RGFP=RGFP966=HDAC3 inhibitor; rh=recombinant human; si=small interfering siRNA; 0.2=0.2 mg/kg treatment dose] .

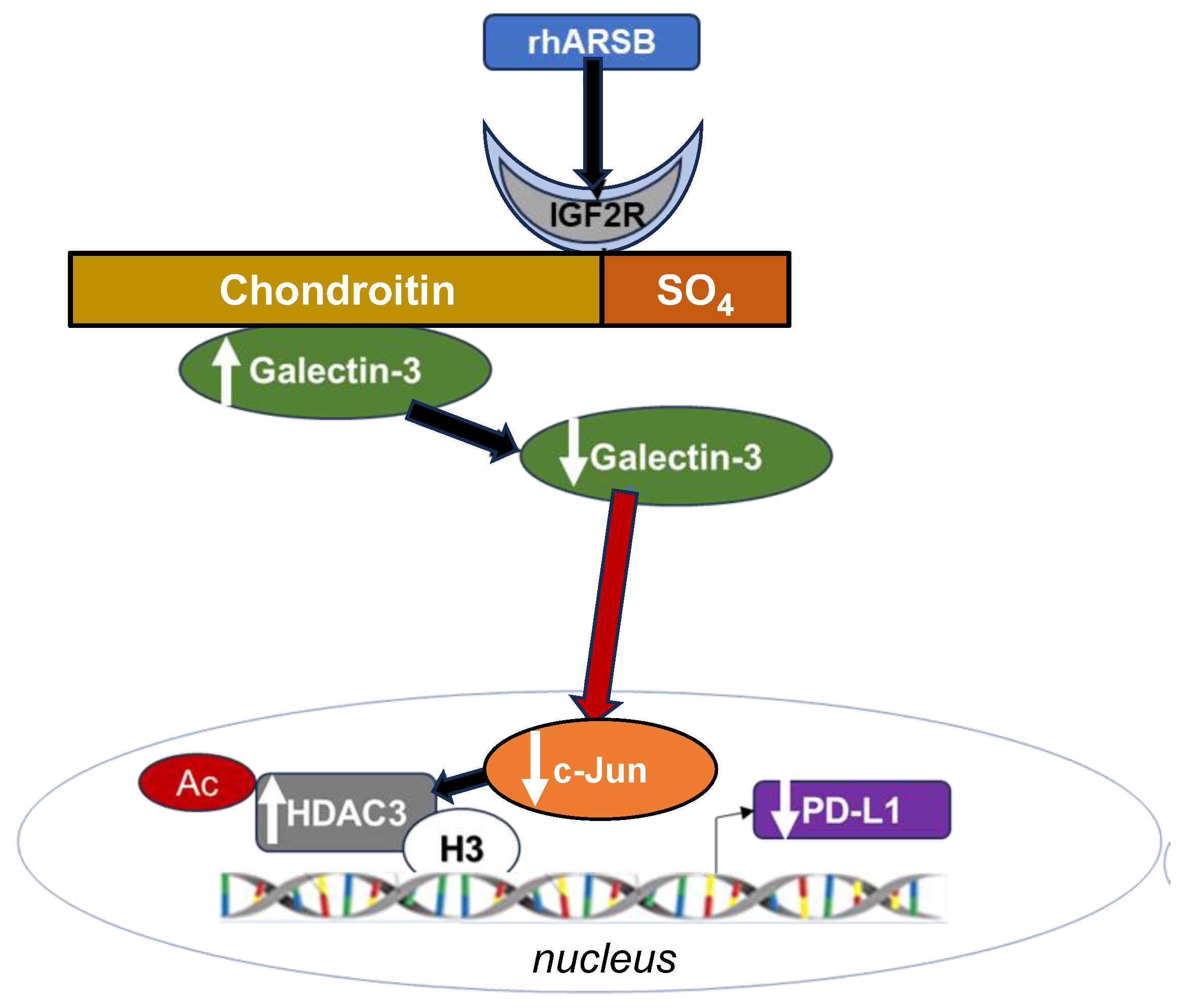

Figure 8.

Schematic of overall pathway. Following exposure to recombinant human ARSB, either in the A375 melanoma cells, normal melanocytes, or mouse subcutaneous B16F10 melanoma, the sulfate group of chondroit. in 4-sulfate is removed and galectin-3 binding with C4S is enhanced. This leads to decline in the free galectin-3 and reduced availability to undergo nuclear translocation and to impact on c-Jun DNA binding, which is then reduced. Reciprocal effects lead to increase in HDAC3, reduced acetyl-H3, increased availability of histone lysines to bind with DNA, leading to closed chromatin, and reduced expression of PD-L1. When ARSB is silenced, opposite effects occur, due to increased availability of galectin-3 and increased effects of c-jun, reduced HDAC3 activity, reduced binding of histone lysines to promoter DNA, leading to open chromatin, and enhanced PD-L1 expression.

Figure 8.

Schematic of overall pathway. Following exposure to recombinant human ARSB, either in the A375 melanoma cells, normal melanocytes, or mouse subcutaneous B16F10 melanoma, the sulfate group of chondroit. in 4-sulfate is removed and galectin-3 binding with C4S is enhanced. This leads to decline in the free galectin-3 and reduced availability to undergo nuclear translocation and to impact on c-Jun DNA binding, which is then reduced. Reciprocal effects lead to increase in HDAC3, reduced acetyl-H3, increased availability of histone lysines to bind with DNA, leading to closed chromatin, and reduced expression of PD-L1. When ARSB is silenced, opposite effects occur, due to increased availability of galectin-3 and increased effects of c-jun, reduced HDAC3 activity, reduced binding of histone lysines to promoter DNA, leading to open chromatin, and enhanced PD-L1 expression.