Submitted:

15 April 2024

Posted:

16 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Data

3. Pathological Features

3.1. Macroscopic Findings

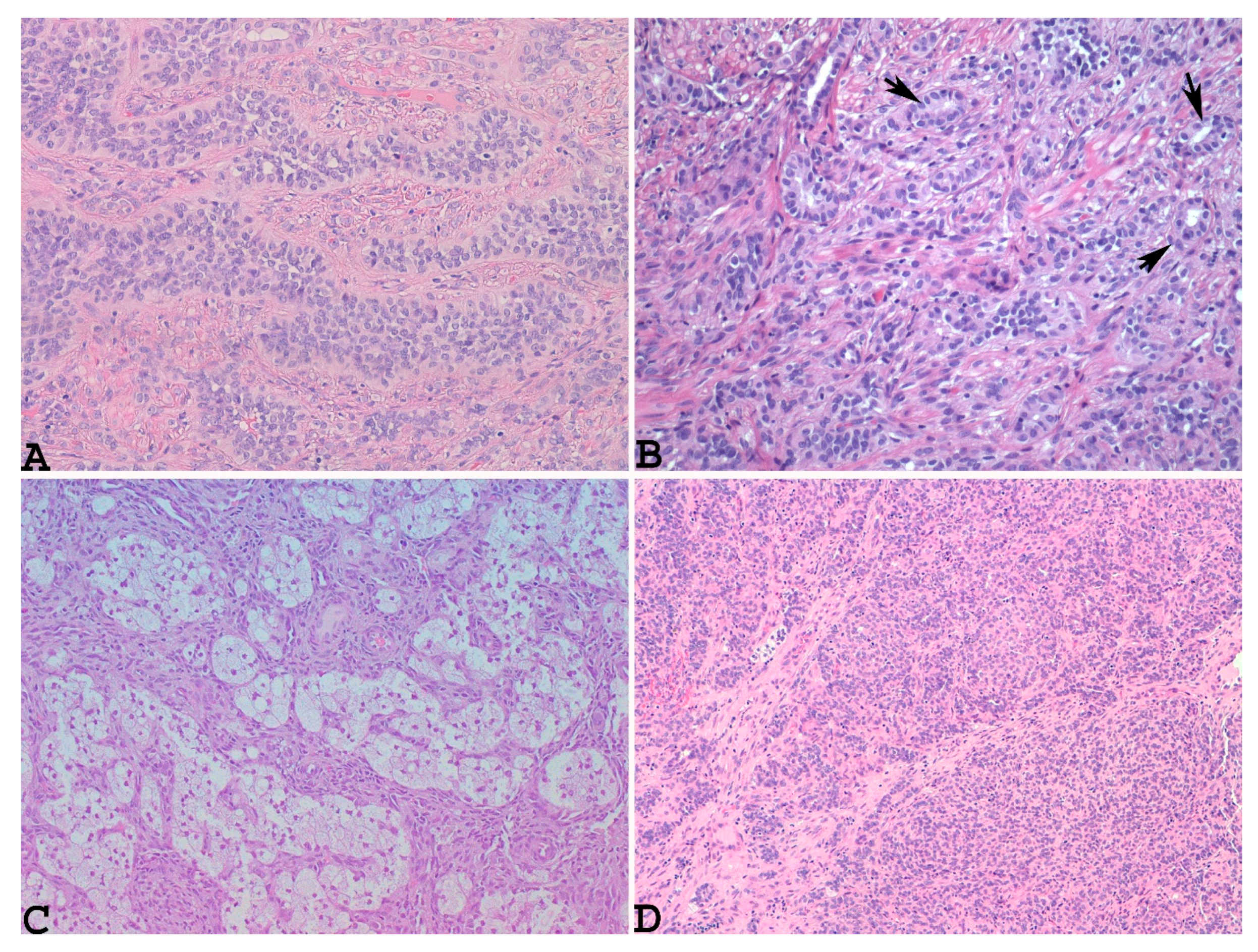

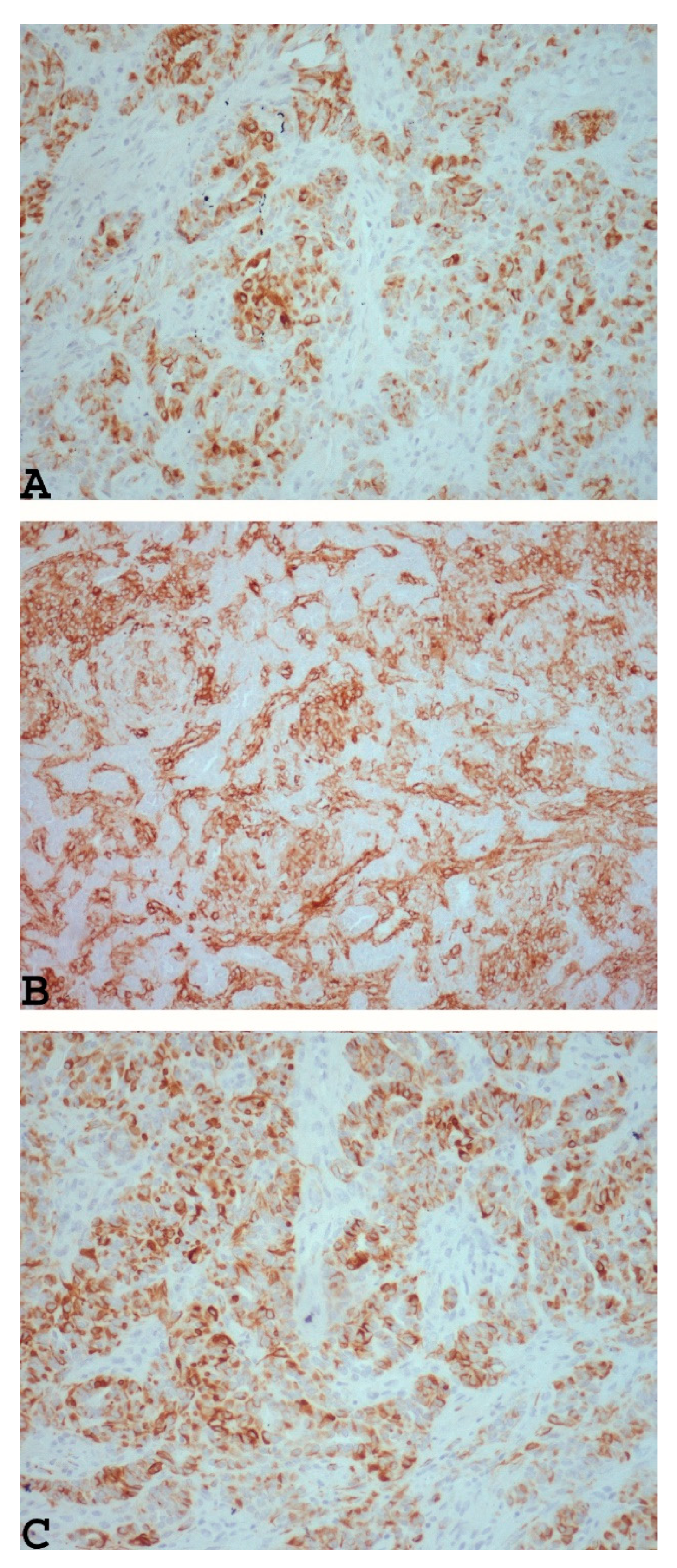

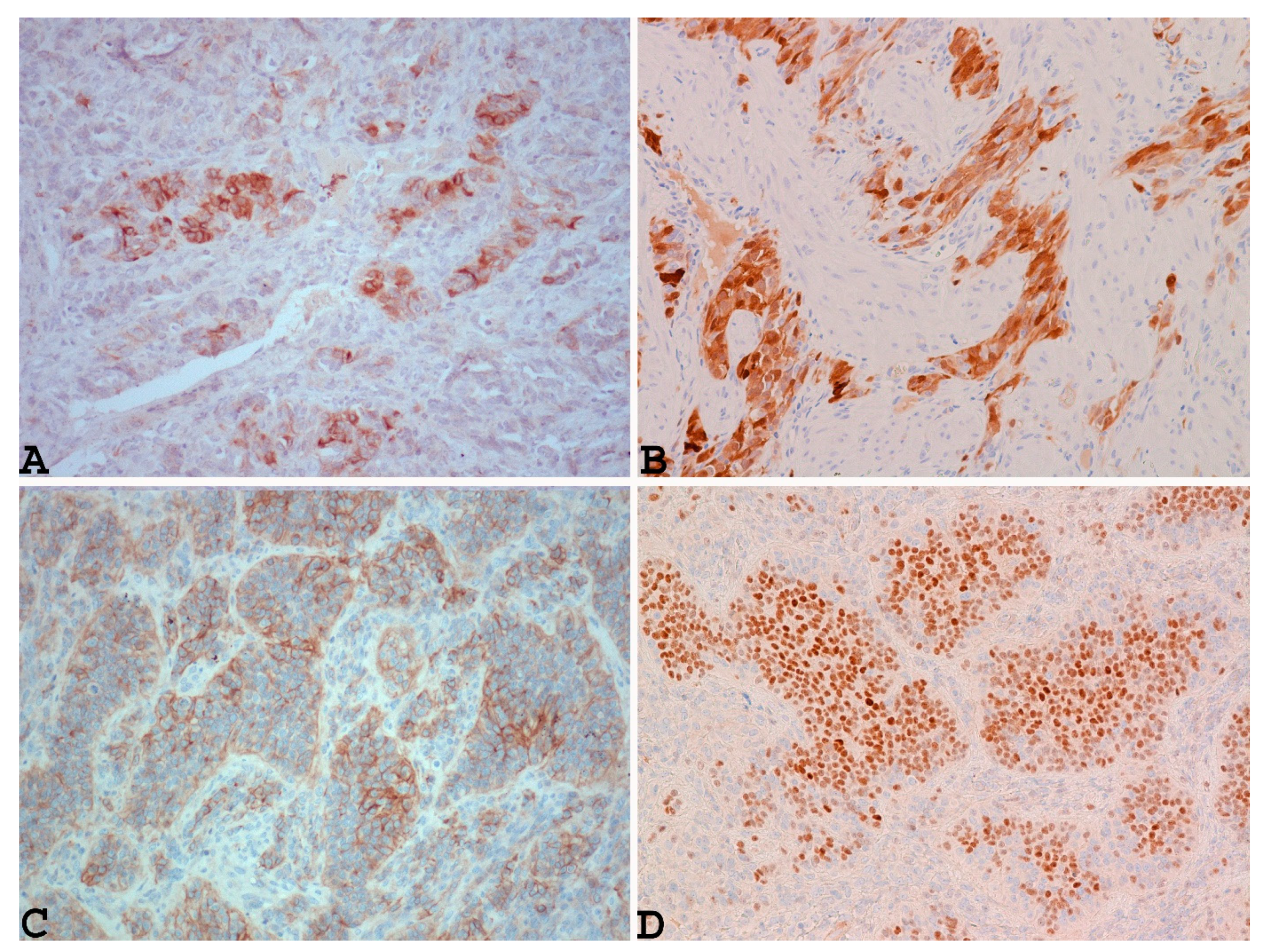

3.2. Microscopic Findings

3.3. Electron Microscopy Findings

4. Impact of Pathological Features on Recurrences or Metastases in UTROSC

5. Molecular Alterations of UTROSC and its Impact on Prognosis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crum, C.P.; Quick, C.M.; Laury, A.R.; Peters, W.A.; Hirsch, M.S. Uterine tumor resembling sex cord stromal tumor. In Gynecologic and Obstetric Pathology. High Yield Patholog; Elsiever: Philadelphia, 2016; pp. 459–460. [Google Scholar]

- Morehead, R.P.; Bowman, M.C. Heterologous mesenchymal tumors of the uterus: Report of a neoplasm resembling a granulosa cell tumor. Am J Pathol. 1945, 21, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clement, P.B.; Scully, R.E. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex-cord tumors: A clinicopathologic analysis of fourteen cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976, 66, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staats, P.N.; Irving, J.A.; McCluggage, W.G. Uterine tumour resembling ovarian sex cord tumour. WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Female Genital Tumours, 5th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Czernobilsky, B. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors: An update. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008, 27, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Level, L.; Lim, G.S.; Waltregny, D.; Oliva, E. Diverse phenotypic profile of uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors: An immunohistochemical study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010, 34, 1749–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staats, P.N.; Garcia, J.J.; Dias-Santagata, D.C.; Kuhlmann, G.; Stubbs, H.; McCluggage, W.G.; De Nictolis, M.; Kommoss, F.; Soslow, R.A.; Iafrate, A.J.; et al. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors (UTROSCT) lack the JAZF1-JJAZ1 translocation frequently seen in endometrial stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009, 33, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.; McCluggage, W.G. Uterine tumour resembling ovarian sex cord tumour: First report of a large series with follow-up. Histopathology. 2017, 71, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolnicu, S.; Balachandran, K.; Aleykutty, M.A.; Loghin, A.; Preda, O.; Goez, E.; Nogales, F.F. Uterine adenosarcomas overgrown by sex-cord-like tumour: Report of two cases. J Clin Pathol. 2009, 62, 942–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, C.; Houghton, O.P.; McCluggage, W.G. Juvenile granulosa cell tumour arising in ovarian adenosarcoma: An unusual form of sarcomatous overgrowth. Hum Pathol. 2015, 46, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, S.; de Kock, L.; Boshari, T.; Hostein, I.; Velasco, V.; Foulkes, W.D.; McCluggage, W.G. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor (UTROSCT) Commonly Exhibits Positivity With Sex Cord Markers FOXL2 and SF-1 but Lacks FOXL2 and DICER1 Mutations. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2016, 35, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, S.; Staats, P.N.; Senz, J.; Kommoss, F.; De Nictolis, M.; Huntsman, D.G.; Gilks, C.B.; Oliva, E. FOXL2 mutation is absent in uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015, 39, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztekin, O.; Soylu, F.; Yigit, S.; Sarica, E. Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumors in a patient using tamoxifen: Report of a case and review of literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006, 16, 1694–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargiulo, M.N.; Capellino, P.; Bacigaluppi, A.D.; Cassanello, G.; Guagnini, M.C.F.; Danieli, F.P.; Crivelli, R. Tumor endometrial sìmil tumor de cordones sexuales asociado al uso de tamoxifeno. Revista del HPC, 2008; 11, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Nogales, F.F.; Stolnicu, S.; Harilal, K.R.; Mooney, E.; García-Galvis, O.F. Retiform uterine tumours resembling ovarian sex cord tumours. A comparative immunohistochemical study with retiform structures of the female genital tract. Histopathology. 2009, 54, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, G.; Lombardi, M.; Brigati, F.; Mancini, C.; Silini, E.M. Clinicopathologic features of 2 new cases of uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010, 29, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Pecharroman, A.; Tirado-Zambrana, P.; Pascual, A.; Rubio-Marin, D.; García-Cosío, M.; Moratalla-Bartolomé, E.; Palacios, J. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor Associated With Tamoxifen Treatment: A Case Report and Literature Review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014, 33, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segala, D.; Gobbo, S.; Pesci, A.; Martignoni, G.; Santoro, A.; Angelico, G.; Arciuolo, D.; Spadola, S.; Valente, M.; Scambia, G.; et al. Tamoxifen related Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor (UTROSCT): A case report and literature review of this possible association. Pathol Res Pract. 2019, 215, 1089–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.A.; Lastra, R.R.; Barroeta, J.E.; Parilla, M.; Galbo, F.; Wanjari, P.; Young, R.H.; Krausz, T.; Oliva, E. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Stromal Tumor (UTROSCT): A Series of 3 Cases With Extensive Rhabdoid Differentiation, Malignant Behavior, and ESR1-NCOA2 Fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020, 44, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyraz, B.; Watkins, J.C.; Young, R.H.; Oliva, E. Uterine Tumors Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumors: A Clinicopathologic Study of 75 Cases Emphasizing Features Predicting Adverse Outcome and Differential Diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2023, 47, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabbani, W.; Deavers, M.T.; Malpica, A.; Burke, T.W.; Liu, J.; Ordoñez, N.G.; Jhingran, A.; Silva, E.G. Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex-cord tumor: Report of a case mimicking cervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2003, 22, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillard, J.B.; Malpica, A.; Ramirez, P.T. Conservative management of a uterine tumour resembling an ovarian sex cord-stromal tumour. Gynecol Oncol. 2004, 92, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasakis, E.; Magos, A.L.; Mould, T.; Economides, D.L. Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumors treated by hysteroscopy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008, 101, 194–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berretta, R.; Patrelli, T.S.; Fadda, G.M.; Merisio, C.; Gramellini, D.; Nardelli, G.B. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors: A case report of conservative management in young women. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009, 19, 808–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garuti, G.; Gonfiantini, C.; Mirra, M.; Galli, C.; Luerti, M. Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumors treated by resectoscopic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009, 16, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakula-Zalewska, E.; Danska-Bidzinska, A.; Kowalewska, M.; Piascik, A.; Nasierowska-Guttmejer, A.; Bidzinski, M. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors, a clinicopathologic study of six cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014, 18, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.H.; Lee, H.N.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, M.L.; Seong, S.J.; Shin, E. Successful delivery after conservative resectoscopic surgery in a patient with a uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with myometrial invasion. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015, 58, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watrowski, R.; Jäger, C.; Möckel, J.; Kurz, P.; Schmidt, D.; Freudenberg, N. Hysteroscopic treatment of uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord-like tumor (UTROSCT). Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015, 31, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Franciscis, P.; Grauso, F.; Ambrosio, D.; Torella, M.; Messalli, E.M.; Colacurci, N. Conservative Resectoscopic Surgery, Successful Delivery, and 60 Months of Follow-Up in a Patient with Endometrial Stromal Tumor with Sex-Cord-Like Differentiation. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2016, 2016, 5736865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraag, S.M.; Caduff, R.; Dedes, K.J.; Fink, D.; Schmidt, A.M. Uterine Tumors Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumors - Treatment, recurrence, pregnancy and brief review. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017, 19, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondi, G.; Tesei, M.; De Crescenzo, E.; Boussedra, S.; Giunchi, S.; Perrone, A.M.; De Iaco, P. Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex-cord tumor: A case report of recurrence after conservative management and review of the literature. Gynecol Pelvic Med. 2021, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.V.; Cavaliere, A.F.; Fedele, C.; Vidiri, A.; Aciuolo, D.; Zannoni, G.; Scambia, G. Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex-cord tumor: Conservative surgery with successful delivery and case series. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021, 256, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraoui, G.; Sassi, F.; Charfi, L.; Ltaief, F.; Doghri, R.; Mrad, K. Unusual presentation of uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumor: A rare case report of cervical involvement. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023, 108, 108477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, J.A.; Carinelli, S.; Prat, J. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors are polyphenotypic neoplasms with true sex cord differentiation. Mod Pathol. 2006, 19, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cömert, G.K.; Kiliç, Ç.; Çavuşoğlu, D.; Türkmen, O.; Karalok, A.; Turan, T.; Başaran, D.; Boran, N. Recurrence in Uterine Tumors with Ovarian Sex-Cord Tumor Resemblance: A Case Report and Systematic Review. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2018, 34, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, G.K.; Wajman, D.S.; Bidmead, J.; Diaz-Cano, S.J.; Arshad, S.; Bakhit, M.; Lewis, D.; Aylwin, S.J.B. Ectopic hyperprolactinaemia due to a malignant uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumors (UTROCST). Pituitary 2020, 23, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, C.; Matsumoto, T.; Fukunaga, M.; Itoga, T.; Furugen, Y.; Kurosaki, Y.; Suda, K.; Kinoshita, K. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex-cord tumors producing parathyroid hormone-related protein of the uterine cervix. Pathol Int. 2002, 52, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Xia, Y.; Chen, J.; Tang, J.; Shao, Y.; Yu, W. NCOA1/2/3 rearrangements in uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor: A clinicopathological and molecular study of 18 cases. Hum Pathol. 2023, 135, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullazade, S.; Kosemehmetoglu, K.; Adanir, I.; Kutluay, L.; Usubutun, A. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors: Synchronous uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors and ovarian sex cord tumor. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010, 14, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, J.G.; Qu, P.P. Clinical experience of uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors: A clinicopathological analysis of 6 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015, 8, 4158–4164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bi, R.; Yao, Q.; Ji, G.; Bai, Q.; Li, A.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Tu, X.; Yu, L.; Chang, B.; et al. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumors: 23 Cases Indicating Molecular Heterogeneity With Variable Biological Behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2023, 47, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantelip, B.; Cloup, N.; Dechelotte, P. Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumors: Report of a case with ultrastructural study. Hum Pathol. 1986, 17, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, K.; Heukamp, L.C.; Büttner, R.; Zhou, H. Uterine tumor resembling an ovarian sex cord tumor associated with metastasis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008, 27, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Meara, A.C.; Giger, O.T.; Kurrer, M.; Schaer, G. Case report: Recurrence of a uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex-cord tumor. Gynecol Oncol. 2009, 114, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeda, S.; Tateno, M.; Miyagi, E.; Sakurai, K.; Tanaka, R.; Tateishi, Y.; Tokinaga, A.; Ohashi, K.; Furuya, M. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors (UTROSCT) with metastasis: Clinicopathological study of two cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014, 7, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Mačák, J.; Dundr, P.; Dvořáčková, J.; Klát, J. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors (UTROSCT). Report of a case with lymph node metastasis. Cesk Patol. 2014, 50, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeong, K.H.; Lee, H.N.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, M.L.; Seong, S.J.; Shin, E. Successful delivery after conservative resectoscopic surgery in a patient with a uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with myometrial invasion. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015, 58, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.R.; Carvalho, F.M.; Abrão, M.; Maluf, F.C. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex-cord tumor: A case-report and a review of literature. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2015, 15, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, D.; Todo, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Suzuki, H. A case of recurrent group II uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex-cord tumors, against which two hormonal agents were ineffective. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2016, 55, 751–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viau, M.; Grondin, K.; Grégoire, J.; Renaud, M.C.; Plante, M.; Sebastianelli, A. Clinicopathological features of two cases of uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex-cord tumors (UTROSCTs) and a comprehensive review of literature. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2017, 38, 93–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.; McCluggage, W.G. Uterine tumour resembling ovarian sex cord tumour: First report of a large series with follow-up. Histopathology. 2017, 71, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznicki, M.L.; Robertson, S.E.; Hakam, A.; Shahzad, M.M. Metastatic uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor: A case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017, 22, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Sakaguchi, S.; Mikubo, M.; Naito, M.; Shiomi, K.; Ohbu, M.; Satoh, Y. Lung metastases of a uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex-cord tumor: Report of a rare case. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018, 46, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrucci, O.; Nicoletti, P.; Mauriello, A.; Facchetti, S.; Patrizi, L.; Ticconi, C.; Sesti, F.; Piccione, E. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumors Type II with Vaginal Vault Recurrence. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2019, 2019, 5231219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croce, S.; Lesluyes, T.; Delespaul, L.; Bonhomme, B.; Pérot, G.; Velasco, V.; Mayeur, L.; Rebier, F.; Ben Rejeb, H.; Guyon, F.; et al. GREB1-CTNNB1 fusion transcript detected by RNA-sequencing in a uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor (UTROSCT): A novel CTNNB1 rearrangement. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2019, 58, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goebel, E.A.; Hernandez Bonilla, S.; Dong, F.; Dickson, B.C.; Hoang, L.N.; Hardisson, D.; Lacambra, M.D.; Lu, F.I.; Fletcher, C.D.M.; Crum, C.P.; et al. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor (UTROSCT): A Morphologic and Molecular Study of 26 Cases Confirms Recurrent NCOA1-3 Rearrangement. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020, 44, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Rajeshwari, M.; Gurung, N.; Kumar, H.; Sharma, M.C.; Yadav, R.; Kumar, S.; Manchanda, S.; Singhal, S.; Mathur, S.R. Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor: A series of six cases displaying varied histopathological patterns and clinical profiles. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2020, 63, S81–S86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, B.; Bai, Q.; Liang, L.; Ge, H.; Yao, Q. Recurrent uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex-cord tumors with the growth regulation by estrogen in breast cancer 1-nuclear receptor coactivator 2 fusion gene: A case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2020, 15, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devereaux, K.A.; Kertowidjojo, E.; Natale, K.; Ewalt, M.D.; Soslow, R.A.; Hodgson, A. GTF2A1-NCOA2-Associated Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor (UTROSCT) Shows Focal Rhabdoid Morphology and Aggressive Behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021, 45, 1725–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bini, M.; Gantzer, J.; Dufresne, A.; Vanacker, H.; Romeo, C.; Franceschi, T.; Treilleux, I.; Pissaloux, D.; Tirode, F.; Blay, J.Y.; et al. ESR1Rearrangement as a Diagnostic and Predictive Biomarker in Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor: A Report of Four Cases. JCO Precis Oncol. 2023, 7, e2300130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, S.P.; Luo, R.Z.; Wang, F.; Yang, X.; Lai, J.P.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L.L. PD-L1 expression, morphology, and molecular characteristic of a subset of aggressive uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor and a literature review. J Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, C.V.; Phung, H.T.; Dao, L.T.; Ta, D.H.H.; Tran, M.N. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor: Clinicopathological Characteristics of a Rare Case. Case Rep Oncol. 2020, 13, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Wu, J.; Yao, L.; He, J. Clinicopathological characteristics and genetic variations of uterine tumours resembling ovarian sex cord tumours. J Clin Pathol. 2022, 75, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, D.P.; McCluggage, W.G. Uterine tumour resembling ovarian sex cord tumour is an immunohistochemically polyphenotypic neoplasm which exhibits coexpression of epithelial, myoid and sex cord markers. J Clin Pathol. 2007, 60, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.J.; Hildebrandt, R.H.; Rouse, R.V.; Hendrickson, M.R.; Longacre, T.A. Inhibin and CD99 (MIC2) expression in uterine stromal neoplasms with sex-cord-like elements. Hum Pathol. 1999, 30, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ise, K.; Tanei, Z.I.; Oda, Y.; Tanikawa, S.; Sugino, H.; Ishida, Y.; Tsuda, M.; Gotoda, Y.; Nishiwaki, K.; Yanai, H.; et al. A Case of Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor With Prominent Myxoid Features. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2024, 43, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubruc, E.; Alvarez Flores, M.T.; Bernier, Y.; Gherasimiuc, L.; Ponti, A.; Mathevet, P.; Bongiovanni, M. Cytological features of uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex-cord tumors in liquid-based cervical cytology: A potential pitfall. Report of a unique and rare case. Diagn Cytopathol. 2019, 47, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.; Mohanty, S.K. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013, 137, 1832–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Busam, K.J.; Rosai, J. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex-cord tumors have an immunophenotype consistent with true sex-cord differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998, 22, 1078–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekete, P.S.; Vellios, F.; Patterson, B.D. Uterine tumor resembling an ovarian sex-cord tumor: Report of a case of an endometrial stromal tumor with foam cells and ultrastructural evidence of epithelial differentiation. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1985, 4, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, R.; Segev, Y.; Schmidt, M.; Schendler, J.; Baruch, T.; Lavie, O. Uterine Tumors Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumors: Case Report of Rare Pathological and Clinical Entity. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017, 2017, 2736710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, B.C.; Childs, T.J.; Colgan, T.J.; Sung, Y.S.; Swanson, D.; Zhang, L.; Antonescu, C.R. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor: A Distinct Entity Characterized by Recurrent NCOA2/3 Gene Fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019, 43, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usadi, R.S.; Bentley, R.C. Endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium with sertoliform differentiation. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1995, 14, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, J.H.; Young, R.H.; Clement, P.B. Sertoliform endometrial adenocarcinoma: A study of four cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1996, 15, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.X.; Patel, K.; Pearl, M.; Liu, J.; Zheng, W.; Tornos, C. Sertoliform endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium with dual immunophenotypes for epithelial membrane antigen and inhibin alpha: Case report and literature review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2007, 26, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.B.; Hart, W.R. Metastases to the uterine corpus from extragenital cancers: A clinicopathologic study of 63 cases. Cancer. 1982, 50, 2163–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Schneider, V. Metastases to the uterus from extrapelvic primary tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1983, 2, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Blakey, G.L.; Zhang, L.; Bane, B.; Torbenson, M.; Li, S. Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor: Report of a case with t(X;6)(p22.3;q23.1) and t(4;18)(q21.1;q21.3). Diagn Mol Pathol. 2003, 12, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusiol, T.; Parolari, A.M.; Piscioli, F. Uterine leiomyoma with tubules. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2008, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, G.; Oliva, E. Smooth muscle tumors of the uterus: A practical approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008, 132, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.A.; Sung, C.J.; Lawrence, W.D.; Quddus, M.R. Vascular plexiform leiomyoma mimicking uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010, 14, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeler, V.M.; Røyne, O.; Thoresen, S.; Danielsen, H.E.; Nesland, J.M.; Kristensen, G.B. Uterine sarcomas in Norway. A histopathological and prognostic survey of a total population from 1970 to 2000 including 419 patients. Histopathology. 2009, 54, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.; Kawar, N.M.; Shin, J.Y.; Osann, K.; Chen, L.M.; Powell, C.B.; Kapp, D.S. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: A population-based analysis. Br J Cancer. 2008, 99, 1210–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, T.W.; Buchanan, R.; Buckley, C.H. Uterine stromal sarcoma following tamoxifen treatment. J Clin Pathol. 1995, 48, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, E. CD10 expression in the female genital tract: Does it have useful diagnostic applications? Adv Anat Pathol. 2004, 11, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; de Level, L.; Selig, M.; Oliva, E.; Nielsen, G.P. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors: An ultrastructural analysis of 13 cases. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2010, 34, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Motoi, T.; Khanin, R.; Olshen, A.; Mertens, F.; Bridge, J.; Dal Cin, P.; Antonescu, C.R.; Singer, S.; Hameed, M.; et al. Identification of a novel, recurrent HEY1-NCOA2 fusion in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma based on a genome-wide screen of exon-level expression data. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012, 51, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosquera, J.M.; Sboner, A.; Zhang, L.; Kitabayashi, N.; Chen, C.L.; Sung, Y.S.; Wexler, L.H.; LaQuaglia, M.P.; Edelman, M.; Sreekantaiah, C.; et al. Recurrent NCOA2 gene rearrangements in congenital/infantile spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013, 52, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaggio, R.; Zhang, L.; Sung, Y.S.; Huang, S.C.; Chen, C.L.; Bisogno, G.; Zin, A.; Agaram, N.P.; LaQuaglia, M.P.; Wexler, L.H.; et al. A Molecular Study of Pediatric Spindle and Sclerosing Rhabdomyosarcoma: Identification of Novel and Recurrent VGLL2-related Fusions in Infantile Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016, 40, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumegi, J.; Streblow, R.; Frayer, R.W.; Dal Cin, P.; Rosenberg, A.; Meloni-Ehrig, A.; Bridge, J.A. Recurrent t(2;2) and t(2;8) translocations in rhabdomyosarcoma without the canonical PAX-FOXO1 fuse PAX3 to members of the nuclear receptor transcriptional coactivator family. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010, 49, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svoboda, L.K.; Harris, A.; Bailey, N.J.; Schwentner, R.; Tomazou, E.; von Levetzow, C.; Magnuson, B.; Ljungman, M.; Kovar, H.; Lawlor, E.R. Overexpression of HOX genes is prevalent in Ewing sarcoma and is associated with altered epigenetic regulation of developmental transcription programs. Epigenetics. 2014, 9, 1613–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, C.B.; Selleri, L. Hox cofactors in vertebrate development. Dev Biol. 2006, 291, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Kao, Y.C.; Lee, W.R.; Hsiao, Y.W.; Lu, T.P.; Chu, C.Y.; Lin, Y.J.; Huang, H.Y.; Hsieh, T.H.; Liu, Y.R.; et al. Clinicopathologic Characterization of GREB1-rearranged Uterine Sarcomas With Variable Sex-Cord Differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019, 43, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.C.; Lee, J.C. An update of molecular findings in uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor and GREB1-rearranged uterine sarcoma with variable sex-cord differentiation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2021, 60, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, S.; Uchiyama, F.; Ohaki, Y.; Kamoi, S.; Kawamura, T.; Kumazaki, T. MRI findings of a case of uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex-cord tumors coexisting with endometrial adenoacanthoma. Radiat Med. 2001, 19, 151–153. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, L.; Dai, Y.; Ren, F.; Peng, X.; Guo, Z. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumors (UTROSCT): Two Case Reports of the Rare Uterine Neoplasm with Literature Review. Curr Med Imaging. 2022, 18, 125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilos, A.G.; Zhu, C.; Abu-Rafea, B.; Ettler, H.C.; Weir, M.M.; Vilos, G.A. Uterine Tumors Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumors Identified at Resectoscopic Endometrial Ablation: Report of 2 Cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermsen, B.; Bogliatto, F.; Bleeker, M.; Leidi, L.; Trum, H.; Comello, E. Uterine tumour resembling ovarian sex cord tumour (UTROSCT): Experience with a rare disease. Two case reports and overview of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Cases Rev, 2015; 2, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Wang, M.; He, H.; Ru, G.; Zhao, M. Uterine Tumor Resembling Ovarian Sex Cord Tumor With Aggressive Histologic Features Harboring a GREB1-NCOA2 Fusion: Case Report With a Brief Review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2023, 42, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors and year (malignant cases/total of cases) |

Age (ys) | Surgery | Gross appearance | Tumor size (cm) | Microscopic appearance (architecture / rhabdoid features) | Nuclear atypia | Mitotic rate | Tumor margins | LVI | Necrosis | Stage | Molecular findings | Site and time of recurrence/ metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kantelip et al., 1985 (1/1 case) ref (42) |

86 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Multiple intamyometral cysts filled with hemorragic and necrotic fluid, surrounded by a fibrotic capsule | Ranging from 2 to 10 | Cords, trabeculae, nests, tubules | Not significant | <1/10 HPF | Well circumscribed | Absent | Present | NR | NR | One nodule in the left ovary and two epiploic nodules present at the time of diagnosis |

|

Biermann et al., 2007 (1/1 case) ref (43) |

68 | NR | Graysh-yellow intramyometral nodule | 4.5 | Tubules, pseudorosettes, sheets, cords | Not significant | Ki-67 < 5% | Focally infiltrative | Absent | NR | NR | NR | Mesentery and small bowel (48 mo) |

|

O’Meara et al., 2009 (1/1 case) ref (44) |

35 | Hysterectomy | Soft and partly cystic yellow mass | 9.9 | Sertoliform | NR | Ki-67 = 5% | Expansive /serosal infiltration | NR | NR | NR | NR | Bladder, abdominal and intestinal wall, peritoneum, ovaries, lymph nodes (36 mo) |

|

Umeda et al., 2014 (2/2 cases) ref (45) |

38 | Transvaginal myomectomy followed by total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy + LND | Yellowish-white intramyometral mass | 4.5 | Solid, cords, tubules | Not significant | 1/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Present | Absent | NR | NR | Left internal iliac lymph node methastasis present at the time of diagnosis |

| 57 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Polypoid submucosal mass | 6.4 | Cords, tubules | Not significant | 0/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Present | Absent | NR | NR | Nodule in the epiploic appendix at the time of diagnosis | |

|

Mačák et al., 2014 (1/1 case) ref (46) |

53 | Polyectomy followed by hysteresctomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Polypoid mass and intramyometral mass | 1.5 and 1.5 | Solid nests, trabeculae, ribbons | Not significant | <1/10 HPF | NR | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Pelvic limph node methastatis at the time of diagnosis |

|

Liu et al., 2015 (1/6 cases) ref (40) |

50 | Trans-vaginal submucosal myomectomy | Isthmus mass protruding through cervical os | 4.5 | NR | NR | NR | Well circumscribed | Absent | NR | NR | NR | Local recurrence (10 mo) |

|

Jeong et al., 2015 (1/1 case) ref (47) |

32 | Submucosal resection | Submucosal protruding mass | 3.6 | Cords, tubules and nests | NR | NR | Infiltrative | NR | NR | NR | NR | Local recurrence (17 mo) |

|

Gomes et al., 2015 (1/1 case) ref (48) |

53 | Supracervical hysterectomy followed by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, parametrectomy, uterine cervical resection + LND | Myometral mass | 12 | Cords, trabeculae | NR | NR | Infiltrative | Present | Present | NR | NR | Parametrial and right ovarian hilum involvement present at the time of diagnosis |

|

Endo et al., 2016 (1/1 case) ref (49) |

62 | Hysterectomy | NR | NR | Trabeculae, nests, cords | Not significant | Ki-67 < 5% | Myometral infiltration | NR | NR | NR | NR | Pelvic limph-node (23 yr) |

|

Viau et al., 2017 (1/2 cases) ref (50) |

43 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy + debulking | Peduncolated solid mass attached to the uterine fundus, with ruptured surface and whitish-yellow colour and solid subserosal mass in the anterior myometrium | 13 and 5.5 | Solid, trabeculae | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | IIB | NR | Pelvis (40 mo). Sigmoid serosa and peritoneal implants present at the time of diagnosis. |

|

Schraag et al., 2017 (2/3 cases) ref (30) |

24 | Submucosal resection | Submucosal nodule | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Local recurrence (9 mo) |

| 28 | Partial resction (due to intraoperative complication) followed by fertility sparing surgery. Hysterectomy + partial bilateral salpingectomy after delivery | Cystic-solid tumor in the anterior uterine wall | 10 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Initial persistence of disease (3 mo). Pelvis, peritoneum, right fallopian tube, ovaries, vagina (39 mo) |

|

|

Moore and McCluggage, 2017 (8/34 cases) ref (51) |

44 | Hysterectomy | NR | 12.5 | NR | Not significant | ≥2/10 HPF |

NR | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Para-aortic limph nodes, peritoneum (11 mo) |

| 75 | NP | NR | NA | NR | Not significant | ≤1/10 HPF | NR | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Para-aortic limph nodes, retroperitoneal and sacral metastatis present at the time of diagnosis | |

| 62 | Hysterectomy | NR | 7 | NR | Not significant | ≤1/10 HPF | NR | Absent | Present | NR | NR | Peritoneum, lung (33 mo) |

|

| 43 | Hysterectomy | NR | 1 | NR | Not significant | ≥2/10 HPF |

NR | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Pelvis, peritoneum (25 mo) |

|

| 47 | Hysterectomy | NR | 6 | NR | Not significant | ≤1/10 HPF | NR | Absent | Present | NR | NR | Vertebra, ovary (78 mo) |

|

| 68 | Hysterectomy | NR | 8 | NR | Significant | ≥2/10 HPF |

NR | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Death (12 mo) Peritoneum, liver (11 mo) |

|

| 61 | Hysterectomy | NR | 12.5 | NR | Not significant | ≥2/10 HPF |

NR | Present | Present | NR | NR | Death (23 mo) Vertebra, clavicle (12 mo) |

|

| 72 | Hysterectomy | NR | 7 | NR | Not significant | ≥2/10 HPF |

NR | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Death (23 mo) Liver (23 mo) |

|

|

Kuznicki et al., 2017 (1/1 case) ref (52) |

49 | Cytoreductive surgery post NACT | Intramyometrial mass | 6 | Trabeculae, rosette-like structures, nests, tubules |

NR | High | Myometral invasion / tumor present at 1mm from | Present | NR | NR | NR | Death (15 mo) Liver, peritoneum and pelvis (4 mo). Bilateral ovarian and omental metastasis at the time of diagnosis. |

|

Kondo et al., 2018 (1/1 case) ref (53) |

69 | Hysterectomy | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Lung (36 mo) |

|

Cömert et al., 2018 (1/1 case) ref (35) |

61 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Endometrial located tumor, suspect for superficial myometral invasion | 7 | Cords, trabeculae, nests, tubules | NR | 2/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Pelvis, omentum and splenic hilum (60 mo) Pelvis, anterior surface of the abdominal wall (75 mo) |

|

Marrucci et al., 2019 (1/1 case) ref (54) |

54 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Graysh-yellow intramyometral mass with poorly delineated margins | 9 | Trabeculae, alveolar-like structures, tubules | NR | 3/10 HPF | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Vaginal vault (59 mo) |

|

Croce et al., 2019 (1/1 case) ref (55) |

70 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Yellow, well circumscribed myometral mass | 10 | Diffuse, tubules, nests, trabeculae / focal rhadoid cells | Not significant | 1/10 HPF | Well circumscribed, with serosal involmement | NR | NR | NR | GREB1-CTNNB1 fusion | Pelvis (17 mo) Lung and peritoneum (29 mo) |

|

Goebel et al., 2020 (1/26 cases) ref (56) |

74 | Hysterectomy | NA | 13 | Cords, trabeculae, sertoliform, retiform | NR | 1/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | NR | NR | GREB1-NCOA2 fusion | Pelvis (66 mo) |

|

Kaur et al., 2020 (1/6 cases) ref (57) |

47 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Mass in the uterine body | 9.3 | Cords, nests, trabeculae, sheets | Not significant | 1-3/10 HPF | Infiltrative | NR | Absent | NR | NR | Pelvis, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, lungs (7 mo) |

|

Chang et al., 2020 (1/1 case) ref (58) |

57 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Intramyometrial, well circumscribed, soft, yellow mass | 10 | Diffuse sheets, nests, cords, trabeculae, glands | Not significant | 3/10 HPF | Infiltrative | NR | Absent | IB | GREB1-NCOA2 fusion | Pelvis (30 mo) |

|

Bennett et al., 2020 (3/3 cases) ref (19) |

37 | Hysterectomy | Yellow white myometral mass | NA | Sheets, cords, trabeculae, occasional pseudopapillary appereance / extensive Rhabdoid component | NR | 0/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Suspect | Absent | I | ESR1-NCOA2 fusion | Pelvis (7 yr) |

| 54 | Supracervical hysterectomy followed by complection trachelectomy and staging | Multiple red brown myometral nodules | Ranging from 1.5 to 6.5 | Sheets, cords, trabeculae, occasional pseudopapillary appereance /extensive rhabdoid component | NR | 4/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | II | ESR1-NCOA2 fusion | Pelvis (9 yr). Cervical involvement and paratubal soft tissue localization at the time of dagnosis |

|

| 30 | Hysterectomy | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ESR1-NCOA2 fusion | Omentum (32 yr and 34 yr) Rectosigmoid nodule (38 yr) |

|

|

Dimitriadis et al., 2020 (1/1 case) ref (36) |

46 | Hysterectomy followed by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Well circumscribed uterine mass | 11 | Sheets, cords, nests, trabeculae | NR | 6/10 HPF | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Intra-abdominal receurrence (24 mo) |

|

Devereaux et al., 2021 (1/1 case) ref (59) |

42 | Myomectomy | Myometral based lesion | 8.8 | Clusters, cords | NR | 2/10 HPF | NA | NR | Present | NR | GFT2A1-NCOA2 fusion (in recurrent tumor) | Uterus, bilateral ovarian surfaces, peritoneum, large bowel serosa, anterior abdominal wall (6 mo) |

|

Dondi et al., 2021 (1/1 case) ref (31) |

24 | Myomectomy | Submucosal mass | 3 | NR | NR | 1/10 HPF | NR | NR | Absent | NR | NR | Local recurrence (20 mo) |

|

Boyraz et al., 2023 (5/75 cases) ref (20) |

32 |

Hysterectomy or excision with negative margins |

NA | 11 | Diffuse, cords | Moderate to severe | 6/10 HPF | Infiltrative, with serosal involvement | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Lung metastasis present at the time of diagnosis |

| 47 | NA | 13 | Diffuse, cords / extensive rhabdoid component. |

Moderate | 7/10 HPF | Infiltrative, with serosal involvement | Absent | Present | NR | NR | Peritoneum (60 mo) |

||

| 58 | NA | 7 | Diffuse, cords | Moderate | 4/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Peritoneum (144 mo) | ||

| 68 | NA | 13 | Diffuse, cords | Moderate | 7/10 HPF | Infiltrative, with serosal involvement | Absent | Absent | NR | NR | Death (96 mo) Peritoneum (60 mo) |

||

| 73 | NA | 3 | Diffuse, cords | Moderate to severe | 9/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Present | NR | NR | Death (50 mo) Brain (30 mo) Femour (48 mo) |

||

|

Bini et al., 2023 (4/4 cases) ref (60) |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4/50 HPF | NR | NR | NR | NR | ESR1-NCOA2 fusion | All patients had metastatic disease and recived several sistemic treatments. After a median of 13.5 years of follow up (6 to 34 years), 3 patients died of disease. |

| NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 8/50 HPF | NR | NR | NR | NR | ESR1-NCOA3 fusion |

||

| NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5/50 HPF | NR | NR | NR | NR | ESR1-NCOA2 fusion | ||

| NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1/50 HPF | NR | NR | NR | NR | NA | ||

|

Bi et al., 2023 (7/22 cases, 1 already reported by Chen et al., 2021) ref (40) |

33 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy + LND | Endometrial thickening, intramyometral mass | 2 | Retiform, papillae, nests, diffuse, whorls, sex cords | Not significat | <1/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | IIIC | GREB1-NCOA2 fusion | Death (177 mo) Retroperitoneal recurrence with abdominal aorta involvement (167 mo) Pelvic lymph nodes involvement presents at the time of diagnosis |

| 48 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Intramyometral solid mass, partially cystic | 13 | Nests, sex cords, sertoliform trabeculae | Not significat | 1/10 HPF | Well-circumscribed | Absent | Absent | IB | GREB1-NCOA2 fusion | Pelvis and omentum (45 mo) |

|

| 38 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Intramyometrial solid mass | NA | Nests, diffuse, sex cords / focal rhabdoid cells. |

Not significat | NA | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | NA | GREB1-NCOA2 fusion | Pelvis and omentum (101 mo) |

|

| 48 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Protuberant and intramyometral solid mass | 3.5 | Diffuse, focal whorls, pseudopapillae, retiform, few cords | Not significat | <1/HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | IIB | GREB1-NCOA1 fusion | Pelvis (13 mo). Peritoneal involvement present at the time of diagnosis. |

|

| 65 | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Intramyometrial solid mass | 15 | Diffuse, sex cords, whorls, sertoliform trabeculae | Not significat | 3/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | IB | GREB1-NCOA1 fusion | Death (44 mo) Pelvis (35 mo) |

|

| 40 | Polypectomy | Polypoid mass | 4 | Sex cords, sertoliform trabeculae / Rhabdoid component | Not significat | <1/10 HPF | Well-circumscribed | Absent | Absent | IA | ESR1-NCOA2 fusion | Local recurrence (21 mo and 64 mo) |

|

| 45 | Hysterectomy | Intramyometral solid mass, partially cystic | 8 | Polypoid mass Diffuse, vague sex cords | Mild to moderate | 1/10 HPF | Well-circumscribed | Absent | Absent | IB | ESR1-NCOA3 fusion | Pelvis (56 mo) |

|

|

Xiong et al., 2023 (6/18 cases) ref. (61) |

41 |

Hysterectomy | NR | 5.5 | Sertoliform, nests, cords |

Not significat | 3/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | NR | ESR1-NCOA2 fusion | Peritoneum (144.4 mo) |

| 46 | NA | NR | 2.5 | Sertoliform, retiform | Not significant | 2/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | NR | Negative for NCOA1-3 fusion and JAZF1/SUZ12/PHF1 rearrangement | Death (26.3 mo) Pelvis, colon (2.5 mo) |

|

| 19 | NA | NR | 3 | Cords, trabeculae | Not significant | 2/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | NR | NA | Metastasis (site NA) (69.9 mo) |

|

| 36 | Hysterectomy | NR | 1.5 | Sertoliform, retiform | Significant | 10/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Present | NR | Negative for NCOA1-3 fusion and JAZF1/SUZ12/PHF1 rearrangement | Pelvis, lung (56.5 mo) |

|

| 55 | Hysterectomy | NR | 13 | Sertoliform, cords, trabeculae | Significant | 2/10 HPF | Infiltrative | Absent | Absent | NR | GREB1-NCOA2 fusion | Pelvis, colon (195.3 mo) |

|

| 48 | Hysterectomy | NR | 2.2 | Sertoliform, retiform | NA | NA | Infiltrative | Absent | NA | NR | NA | Lung (21.1 mo) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).