Submitted:

18 April 2024

Posted:

18 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

4. Discussion

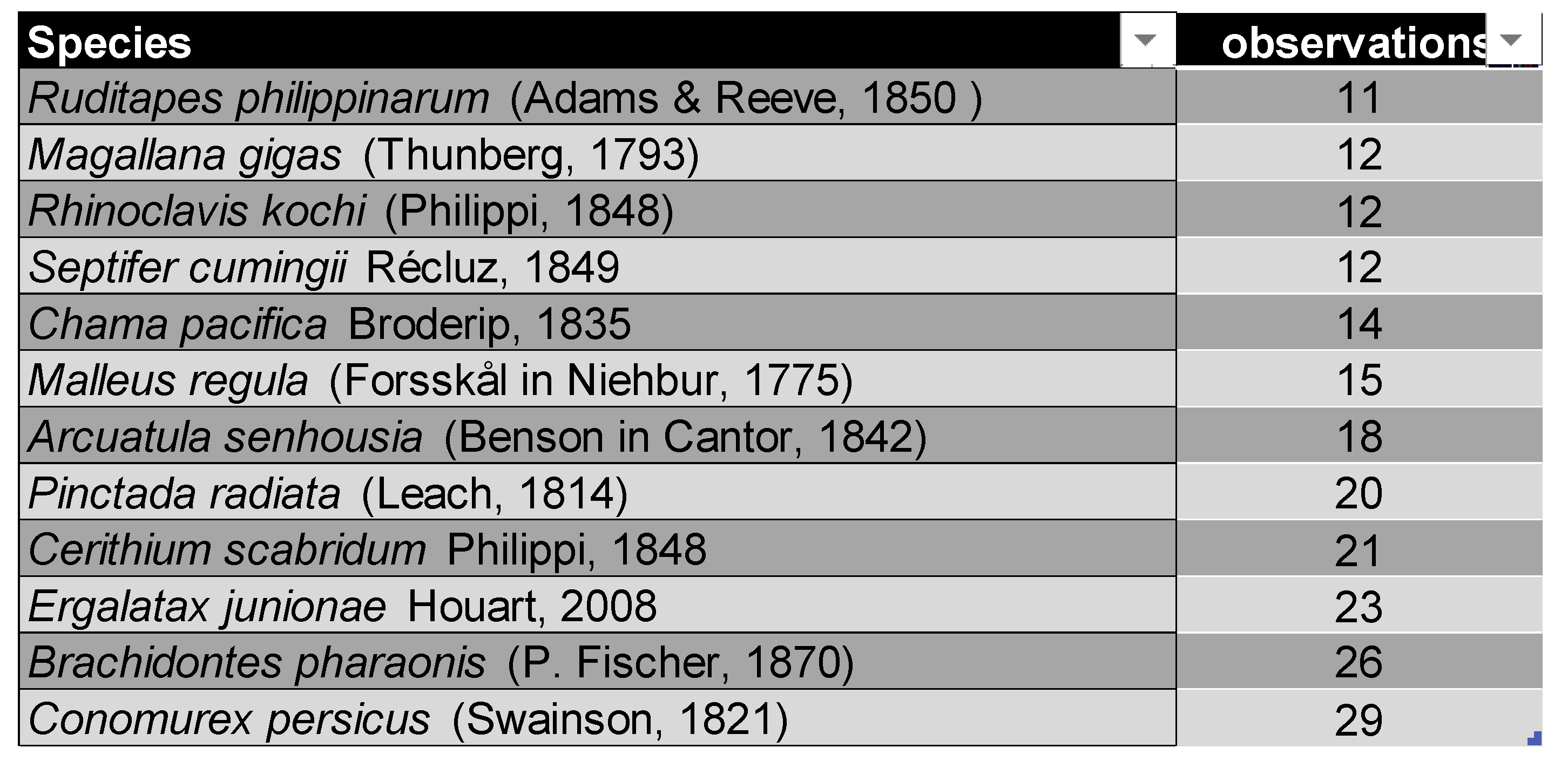

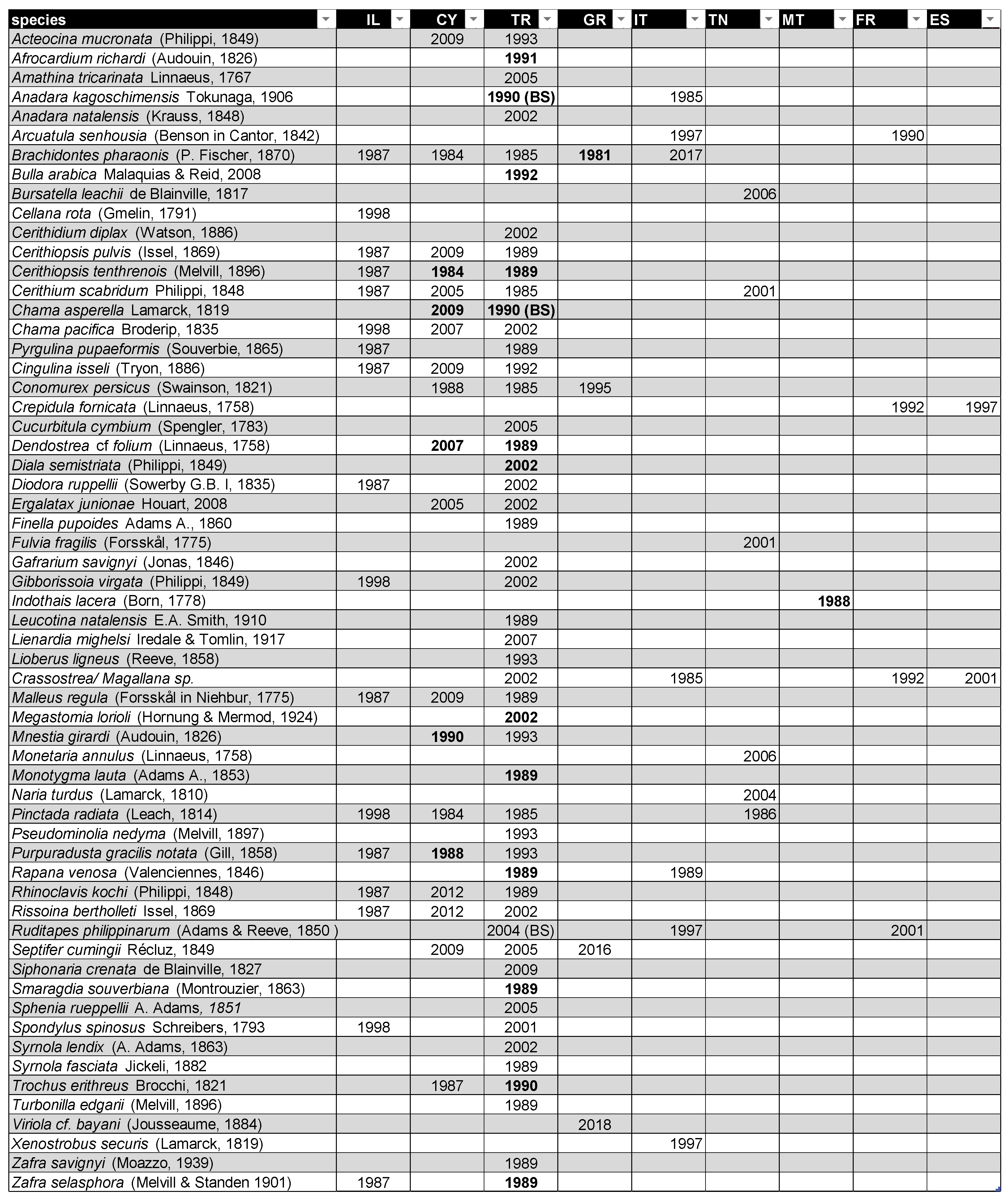

- Brachidontes pharaonis (P. Fischer, 1870) in east Rhodes (Levantine coast of Greece), 1981 backdating the 2010 record for the Levantine MSFD by [30];

- Bulla arabica Malaquias & Reid, 2008 in S. Türkiye 1992, backdating the 2000 record by [31];

- Cerithiopsis tenthrenois (Melvill, 1896) in S. Türkiye 1989, backdating the 2000 record by [32];

- Cerithiopsis tenthrenois (Melvill, 1896) in Cyprus 1984, backdating the 1985 record by [33];

- Purpuradusta gracilis notata (Gill, 1858) in Cyprus 1988, backdating the 2000 record [39];

- Trochus erithreus Brocchi, 1821 in S. Türkiye, 1990, backdating the 1992 record by [38].

References

- Roy, H.; Groom, Q.; Adriaens, T.; Agnello, G.; Antic, M.; Archambeau, A.; Bacher, S.; Bonn, A.; Brown, P.; Brundu, G.; et al. Increasing understanding of alien species through citizen science (Alien-CSI). Res. Ideas Outcomes 2018, 4, ff10. [Google Scholar]

- Encarnação, J.; Teodósio, M.A.; Morais, P. Citizen science and biological invasions: A review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 8, 602980.

- Chandler, M.; See, L.; Copas, K.; Bonde, A.M.; López, B.C.; Danielsen, F.; Legind, J.K.; Masinde, S.; Miller-Rushing, A.J.; Newman, G.; et al. Contribution of citizen science towards international biodiversity monitoring. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 213, 280–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchante, E. , López-Núñez, F.A., Duarte, L.N., & Marchante, H. The role of citizen science in biodiversity monitoring: when invasive species and insects meet. pp. 291-314 In Biological Invasions and Global Insect Decline 2024. Academic Press.

- Johnson, B.A.; Mader, A.D.; Dasgupta, R.; Kumar, P. Citizen science and invasive alien species: An analysis of citizen science initiatives using information and communications technology (ICT) to collect invasive alien species observations. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 21, e00812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iNaturalist. Available online: http://www.inaturalist.org (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- EASIN, European Commission - Joint Research Centre - European Alien Species Information Network (EASIN), 2022, https://easin.jrc.ec.europa.eu / (accessed 2024-03-16).

- Kousteni, V.; Tsiamis, K.; Gervasini, E.; Zenetos, A.; Karachle, P.K.; Cardoso, A.C. Citizen scientists contributing to alien species detection: The case of fishes and mollusks in European marine waters. Ecosphere2022, 13(1), e03875. 10.1002/ecs2.3875.

- Sandahl, A.; Tøttrup, AP. Marine citizen science: recent developments and future recommendations. Citizen Sci: Theory Pract. 2020, 5(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Giovos, I.; Kleitou, P.; Poursanidis, D.; Batjakas, I.; Bernardi, G.; Crocetta, F.; Doumpas, N.; Kalogirou, S.; Kampouris, T.E.; Keramidas, I.; et al. Citizen-science for monitoring marine invasions and stimulating public engagement: A case project from the eastern Mediterranean. Biol. Invasions 2019, 21, 3707–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiralongo, F.; Crocetta, F.; Riginella, E.; Lillo, A.O.; Tondo, E.; Macali, A.; Mancini, E.; Russo, F.; Coco, S.; Paolillo, G.; et al. Snapshot of rare, exotic and overlooked fish species in the Italian seas: A citizen science survey. J. Sea Res. 2020, 164, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, C.; Tanduo, V.; Crocetta, F.; Giovos, I.; Litsiou, S.; Kleitou, P. Engagement of fishers in citizen science enhances the knowledge on alien decapods in Cyprus (eastern Mediterranean Sea). Aquat. Ecol. 2024, 58(1), 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetta, F.; Gofas, S.; Salas, C.; Tringali, L.P.; Zenetos, A. Local Ecological Knowledge versus published literature: a review of Non-Indigenous mollusca in Greek marine waters. Aquat. Invasions 2017, 12, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species. Available from https://www.marinespecies.org at VLIZ. Accessed 2024-04-01. [CrossRef]

- Galanidi, M.; Aissi, M.; Ali, M.; Bakalem, A.; Bariche, M.; Bartolo, A.G.; Bazairi, H.; Beqiraj, S.; Bilecenoglu, M.; Bitar, G.; et al. Validated inventories of non-indigenous species (NIS) for the Mediterranean Sea as tools for regional policy and patterns of NIS spread. Diversity 2023, 15, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Colonisation des côtes de la République Turque de Chypre du Nord par un Muricidae originaire du Golfe Persique (Egalatax Iredale, 1931). NOVAPEX 2008, 9(1), 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Strombus decorus raybaudii en Méditerranée, nouvelles localités de récolte. Arion 1985, 10(6), 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Palmadusta gracilis (Gaskoin, 1849)-Récolte d’un spécimen sur la côte méditerranéenne d’Israël. Arion 1989, 14(1), 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Erosaria turdus (Lamarck, 1810) (Gastropoda - Cypraeidae) dans le Golfe de Gabès (Tunisie). NOVAPEX 2004, 5(4), 147–148. [Google Scholar]

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Illustration de Gastrochaena cymbium Spengler, 1783 en Méditerranée orientale sur Hexaplex pecchiolianus (d’Ancona, 1871). NOVAPEX 2005, 6(4), 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Afrocardium richardi (Audouin, 1826) alive on Spondylus spinosus Schreibers, 1793 in the Gulf of Iskenderun (Eastern Mediterranean Sea). Neptunea, 2006a5(1), 13–14.

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Mollusques associés à Spondylus spinosus Schreibers, 1793 dans le golfe d’Iskenderun (Turquie). NOVAPEX, 2006b, 7(2-3), 29–33.

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Echantillonnage de mollusques invasifs et première signalisation de Chama aspersa Reeve, 1846 à Chypre Nord. NOVAPEX 2010a, 11(1), 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Importante population de Siphonaria crenata Blainville, 1827 implantée à l’ouest du golfe d’Iskenderun (Turquie). NOVAPEX 2010b, 11(1), 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Note concernant la présence de Monetaria annulus (Linnaeus, 1758) dans le Golfe de Gabès. NOVAPEX 2013, 14(4), 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Micali, P.; Palazzi, S. Contributo alla conoscenza dei Pyramidellidae della Turchia, con segnalazione di due nuove immigrazioni dal Mar Rosso. Boll. Malacol. 1992, 28 (1-4), 83-90.

- Buzzurro, G.; Greppi, E. Presenza di Smaragdia (Smaragdella) souverbiana (Montrouzier, 1863) nel Mediterraneo orientale. Boll. Malacol. 1994, 29(9-12), 319–321.

- Palazzi, S. Ci sono due Zafra in Mediterraneo, ma come si chiamano? Notiziario del CISMA 1993, 14, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aartsen J.J., van; Goud, J. European marine Mollusca: notes on less well-known species. XV. Notes on Luisitanian species of Parvicardium Montesoraro, 1884, & Afrocardium richardi (Audouin, 1826) (Bivalvia, Heterodonta, Cardiidae). Basteria, 2000, 64, 171-186.

- Zenetos, A.; Karachle, P.K.; Corsini-Foka, M.; Gerovasileiou, V.; Simboura, N.; Xentidis, N.J.; Tsiamis, K. Is the trend in new introductions of marine non-indigenous species a reliable criterion for assessing good environmental status? The case study of Greece. Meditter. Mar. Sci. 2020, 21, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokes, B.; Rudman, W.B. Lessepsian opisthobranchs from southwestern coast of Turkey: Five new records for Mediterranean. Rapp. Comm. Int. Explor. Mer Méditerranée 2004, 37, 557. [Google Scholar]

- Tringali, L.; Villa, R. Rinvenimenti malacologici dalle coste turche (Gastropoda, Polyplacophora, Bivalvia). Notiziario del CISMA, 1990, 11(12), 33-41.

- Tornaritis, G. Mediterranean Sea Shells. 1987, Nicosia, Cyprus, published by the author. 190 pp.

- Çeviker, D. Recent Immigrant Bivalves in the Northeastern Mediterranean off Iskenderun. La Conchiglia 2001, 298, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zenetos, A.; Konstantinou, F.; Konstantinou, G. Towards homogenization of the Levantine alien biota: Additions to the alien molluscan fauna along the Cypriot coast. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 2009, 6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecalupo, A.; Quadri, P. Contributo alla conoscenza malacologica per il nord dell’isola di Cipro (Parte I). Boll. Malacol. 1994, 30(1-4), 5–16.

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. Les espèces invasives de mollusques en Méditerranée. NOVAPEX 2007, 8(2), 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zenetos, A.; Gofas, S.; Russo, G.; Templado, J. CIESM atlas of exotic species in the Mediterranean. Vol 3. Molluscs. [F. Briand, Ed.] 376 pp. 2004, CIESM Publishers, Monaco.

- Engl, W. Specie prevalentemente Lessepsiane attestate lungo le coste Turche. Boll. Malacol. 1995, 31 (1-4), 43-50.

- Delongueville, C.; Scaillet, R. The genus Lioberus Dall, 1898 (Bivalvia - Mytilidae), some thoughts about its distribution in the Mediterranean Sea. NOVAPEX 2023, 24(2), 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetta, F.; Bitar, G.; Zibrowius, H.; Oliverio, M. Biogeographical homogeneity in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. II. Temporal variation in Lebanese bivalve biota. Aquat. Biol. 2013, 19, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galil, B.S.; Mienis, H.K.; Hoffman, R.; Goren, M. Non-indigenous species along the Israeli Mediterranean coast: Tally, policy, outlook. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 2011–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çinar, M.E.; Bilecenoglu, M.; Yokes, M.B.; Ozturk, B.; Taskin, E.; Bakir, K.; Dogan, A.; Acik, S. Current status (as of end of 2020) of marine alien species in Turkey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenetos, A.; Albano, P.G.; Garcia, E.L.; Stern, N.; Tsiamis, K.; Galanidi, M. Established non-indigenous species increased by 40% in 11 years in the Mediterranean Sea. Meditter. Mar. Sci. 2022a, 23, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenetos, A.; Albano, P.G.; Garcia, E.L.; Stern, N.; Tsiamis, K.; Galanidi, M. Corrigendum to the Review Article (Medit. Mar. Sci. 23/1 2022, 196-212) Established non-indigenous species increased by 40% in 11 years in the Mediterranean Sea. Meditter. Mar. Sci, 2022b, 23, 876-878. [CrossRef]

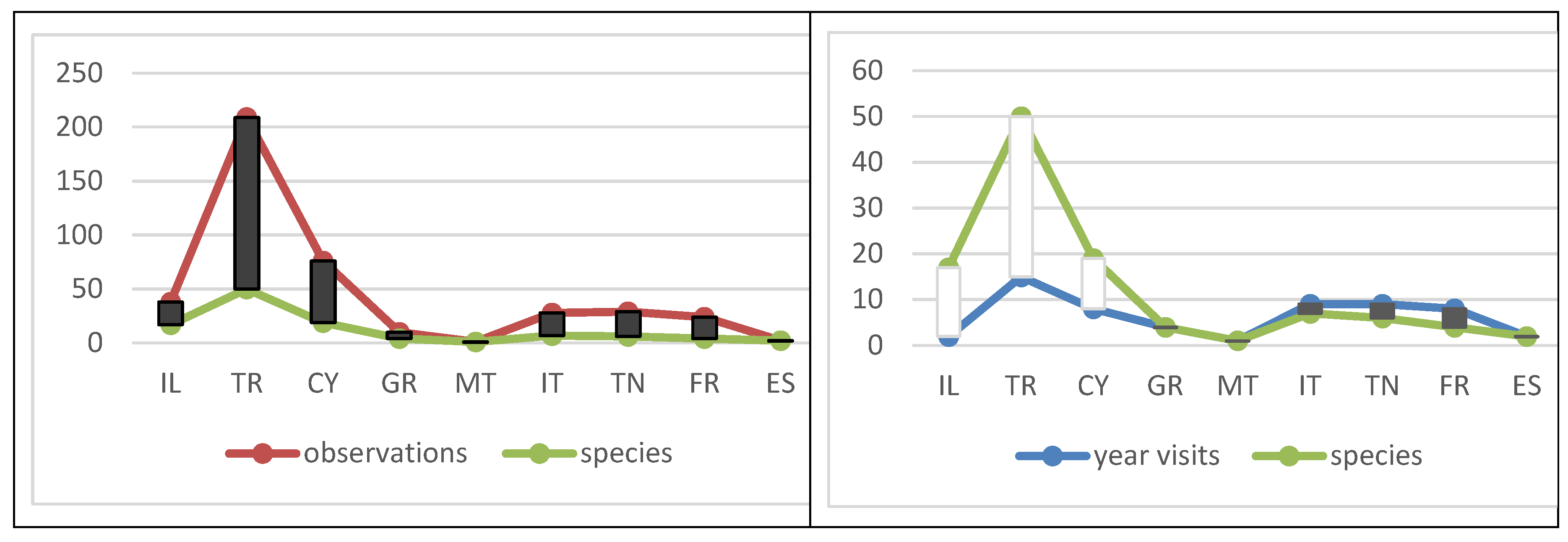

| Country | Year |

|---|---|

| Greece (GR) | 1981, 1995, 2016, 2018 |

| Cyprus (CY) | 1984, 1987, 1988, 1990, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2012 |

| Italy (IT) | 1985, 1987, 1989, 1997, 2000, 2005, 2009, 2012, 2017 |

| Türkiye (TR) | 1986, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012 |

| Israel (IL) | 1987, 1998 |

| Malta (MT) | 1988 |

| France (FR) | 1990, 1992, 1994, 1998, 1999, 2001, 2003, 2009 |

| Spain (ES) | 1997, 2001 |

| Tunisia (TN) | 1986, 1990, 2001, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2010, 2011, 2012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).