1. Introduction

Brazil makes constant efforts to promote Adequate and Healthy Eating (AHE) in different environments, in line with the Brazilian Dietary Guidelines [

1]. The places where we live, work, live and study form the food environment, and impose factors such as the availability and price of products; these in turn directly influence the purchase of food, which can facilitate or hinder AHE, in addition to being permeated by advertisements and social media, also negatively associated with eating habits [

2,

3,

4]. The assessment of food environments is extremely important to understand the determinants of habits and the behaviors.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the school food environment covers all spaces (school canteens, classrooms, courtyards, external areas, cafeterias, self-service machines, street vendors, and others), and the infrastructure in and around schools in which food is offered, purchased and consumed, as well as its form, advertising and price (marketing, advertisements, brands, labels, and food packaging) [

5]. This environment is a suitable place to promote healthy habits, as it is a training and learning space for students, in addition to having a very expressive community of actors: parents, teachers, students, and other employees [

4].

The creation of healthy eating habits must begin in childhood with family members, and must continue in the school environment, where the child spends at least a third of the day and eats one to two meals. This is an important opportunity to encourage consumption of adequate and healthy foods which are essential for physical, psychosocial and academic growth and development, in addition to improving the feeling of well-being and promoting quality of life that is essential in adulthood [

6,

7].

Among Brazilian efforts, we highlight the National School Feeding Program (

Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar – PNAE), which has existed since the 1950s for public schools throughout Brazil, with emphasis on offering school meals. It serves more than 40 million students, decentralized in 5,570 Brazilian municipalities, and follows the Brazilian Dietary Guidelines [

1,

8]. Another highlight is Interministerial Ordinance #1.010, published in 2006; this ordinance is focused on promoting national nutrition education actions in schools, considering the cultural differences of each state and recommending monitoring the nutritional and dietary status of students, implementation of good food handling practices and restriction of the sale of fatty foods and foods with high salt and sugar content in schools [

9]. Then Decree #11.821 was published in 2023, providing principles, objectives, strategic axes and guidelines which guide actions to promote AHE in the school environment [

10].

Despite these initiatives, Brazil’s territorial extension and diversity require assessments and monitoring that have not yet been achieved by the competent bodies. According to the 2019 National School Health Survey (

Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar – PeNSE), 96.2% of private schools and 27.9% of public schools had commercial school canteens, despite these establishments being prohibited in the public network.

PeNSE also showed the sale of soft drinks (75%), industrialized snacks (68.3%) and fried snacks (72.4%) around schools. The presence of soft drinks in canteens was reported in more than half of the sample surveyed, despite their sale already having been discouraged for almost two decades (2006) [

11]. The supply of these foods has a significant impact on students’ eating choices and behavior, with a strong association with the development of excess weight in children and adolescents. Sweetened beverages are responsible for approximately 10% of childhood obesity and ultra-processed foods (UPF) are related to elevated total and LDL cholesterol levels and increased waist circumference in children [

12]. Therefore, it is important to carry out research that analyzes exposure to these foods in order to propose timely changes.

The study “Food Marketing in Brazilian Schools” (

Comercialização de Alimentos em Escolas Brasileiras – CAEB) was carried out in private schools in 19 of the 27 Brazilian capitals. Aracaju, the capital of Sergipe, has only one study on the adequacy of

PNAE menus [

13], and another on commercial canteens in public schools in the state [

14], with this being pioneering research in the city. Therefore, the objective of this study was to analyze the sale of food in private school canteens, verifying exposure and influence on students’ eating behavior.

2. Methods

This is an analytical cross-sectional study carried out in Aracaju, which is the capital city of one of the nine states in the Northeast region of Brazil. It has a population of 672,614 inhabitants [

15], has 161 private schools, 110 of which are at the preschool level, 128 at the primary level, and 61 at secondary level [

16].

The canteens of private primary and secondary schools in the capital were researched to characterize the schools’ food environment. The sample universe was defined based on the School’s catalog of the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (Inep) from 2021. The simple random probabilistic sampling method was used, with primary and secondary education schools being selected. Verification of the canteens’ eligibility was carried out by local researchers through telephone contact and/or other means of communication. After this screening contact, schools that did not have canteens, deactivated schools, schools that were not possible to contact and pre-school education schools were excluded, as they had fewer canteens. Of the 189 private schools in Aracaju, 71 confirmed that they have a school canteen. The replacement method adopted was reverse sampling due to the lack of information regarding the presence of canteens on the Inep list and the expectation that the percentage of schools with a canteen varies between cities, aiming to guarantee the randomness of replacement throughout the data collection. The minimum sample size was 54 schools, and in the end 71 schools participated in the study from October to December 2022.

After contact, the name of the person responsible for carrying out data collection was requested, respecting the location’s workflow, availability and acceptance to participate in the study. For this stage, a company specialized in carrying out the study, Vox Populi, was hired, which was responsible for collecting data from all states participating in the study. The collection in Aracaju also included volunteer students from the nutrition course at the Federal University of Sergipe (UFS) who participated in prior training on the instrument and the data collection procedure, as well as on the confidentiality of the information collected and reliable recording of the data.

The data collection instrument used was developed by the national study team based on the NOVA food classification, and consists of a checklist of 87 questions. The questions extracted for use in this study refer to the profile and identification of the school, information about the canteen, the meals offered (section 1), the food sold (section 2), the production form (whether homemade or industrialized), the reason for choosing these foods for sale, and the presence or absence of a nutritionist and educational materials to promote adequate and healthy eating (section 3).

Frequencies and associations were performed using Pearson’s Chi-Squared test. The analysis of the foods sold was based on the NOVA food classification from the Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population regarding the degree and extent of processing [

1]:

in natura, animal or vegetable origin, which are taken from nature, and distributed for consumption without any alteration; minimally processed, with minimal changes for consumption, such as cutting and drying; processed, made with the addition of oil, salt, sugar or vinegar, to make them last longer; and ultra-processed foods (UPFs), made with many ingredients and generally have additives for exclusively industrial use [

1]. After classifying the degree of processing, the foods sold were quantified and categorized according to the variety present in schools: sales of less than five types and more than six types of food in each category.

An analysis of the canteens’ profile was also carried out using Latent Class Analysis (LCA) [

17]. This statistical procedure sought to group canteens according to similar response patterns modeled with covariates, forming classes with greater homogeneity and interclass heterogeneity. The latent classes were generated from 45 variables that describe the characteristics of the establishments. Models were created and tested in the construction of this latent variable, with different numbers of categories until finding the ideal model to describe this variable. The following criteria were observed for this choice: Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (adjusted BIC), always observing the lowest values when comparing the current model with the previous one.

The Kruskal-Wallis [

18] and Duun [

19] tests were used to test the association of latent classes with the independent variables when crossing with quantitative variables, and the Fisher’s Exact test [

20] when crossing with qualitative variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test [

21] was used to evaluate the adherence of quantitative variables to the Normal distribution. Statistical analyzes were performed using R version 4.3.2 program [

22]. The significance level adopted throughout the work was 5%.

3. Results

The majority of those responsible/managers of the school canteen participated in the study (78.9%), followed by the owners (21.1%), 80.7% of whom were female, with an average age of 29 years (SD±16.6). Moreover, 57.9% had completed secondary education, and 42.1% had completed higher education.

A total of 69.8% of participating schools in Aracaju had fewer than five employees, serving an average of 262 students (SD±265.3). Of these, 50.7% are managed by the school itself in a self-management system, and essentially offer snacks (100%) (

Table 1).

Only 9.9% of schools produce educational materials on healthy eating and those responsible for their preparation are those responsible for the canteens, nutritionists, students and school management. The canteens presented an average of 2.3 (SD±1.2) types of food in the fresh or minimally processed category, 2.1 (SD±1.5) varieties classified as processed and an average of 7.5 types of UPFs (SD±4.0). In total, 98.6% of canteens have less than 5 types of fresh or minimally processed foods as an option for students, compared to 66.2% of canteens which have more than 6 types of UPFs in their canteens (

Table 2).

The presence of a nutritionist on site was associated with the characteristics of the canteens and demonstrated a statistically significant association with the nutritional information available (p<0.001), with the choice of food based on legislation (p=0.022) and with the existence of educational material on healthy eating in the canteen (p=0.038), as shown in

Table 3.

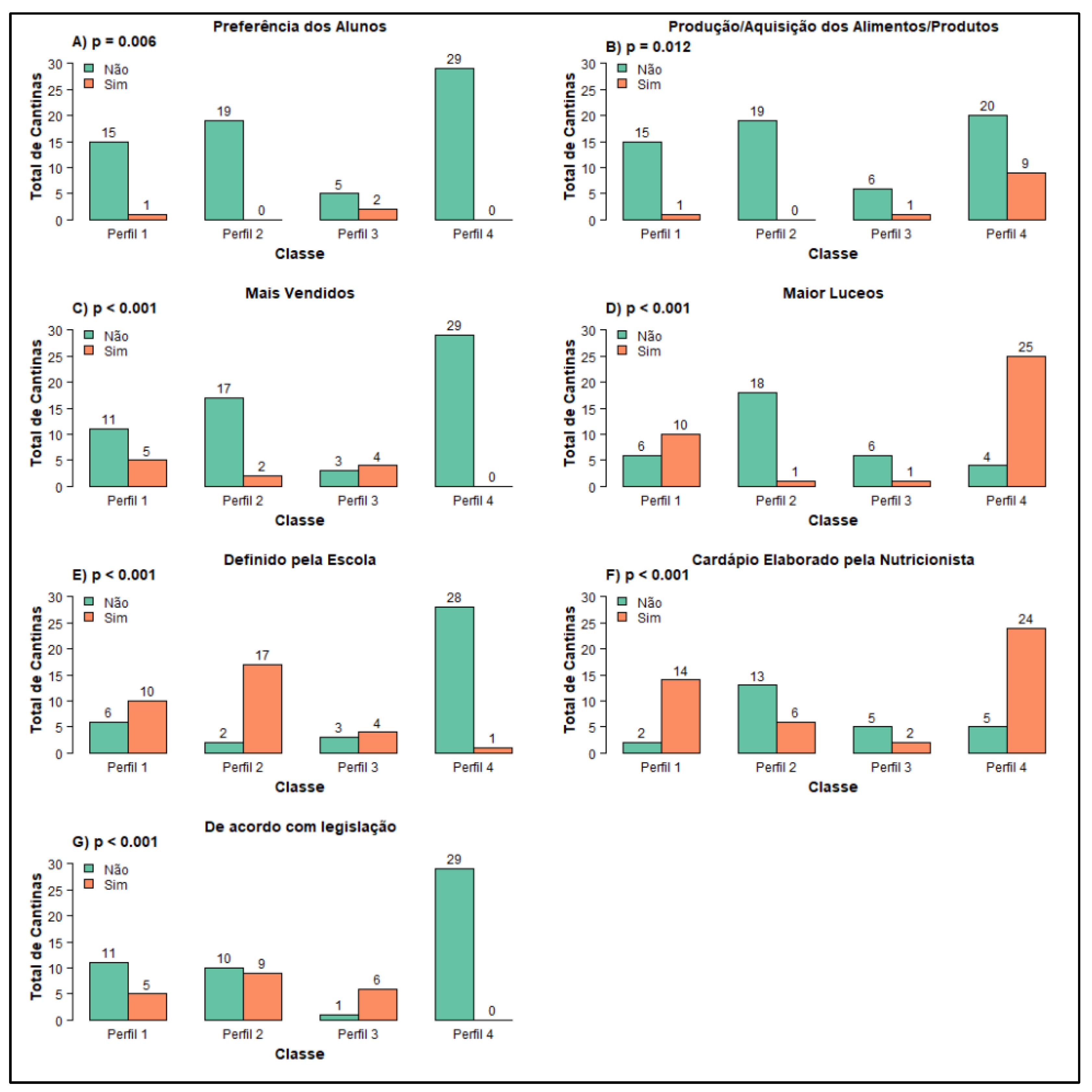

The sale of UPFs in canteens had a statistically significant association with all criteria for choosing foods to be offered in canteens (

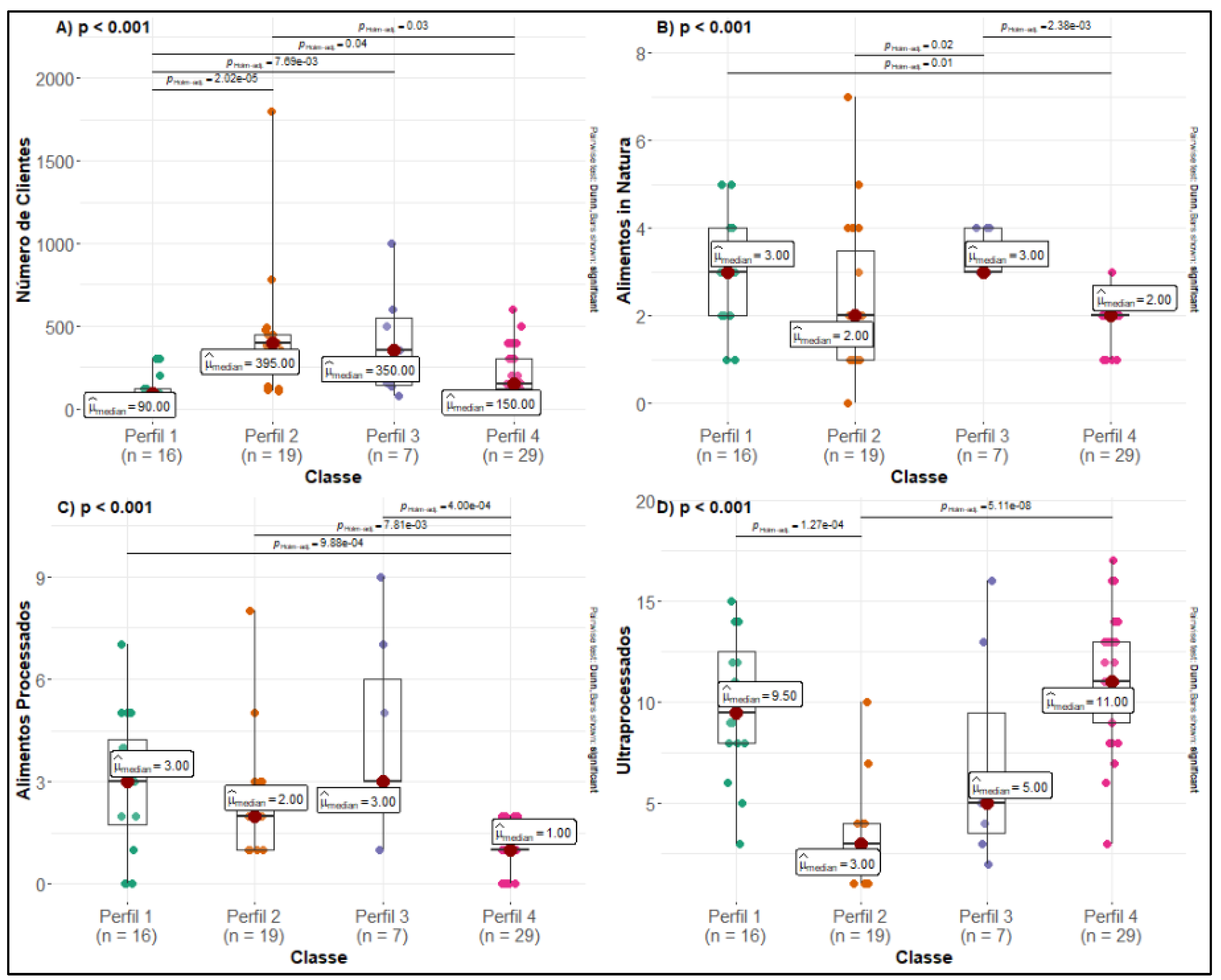

Table 4), except the nutritionist’s decision (p=0.410). The canteen profiles were stratified into four options (described in the supplementary material), and were correlated with the criteria for choosing the foods sold, number of customers served and type of food sold (

Figure 1) and demonstrated statistical significance in all associations (p <0.05).

Figure 2 shows the analysis of the four profiles generated in association with the degree of food processing. Profiles 1 and 4 are characterized by the high probability of having nutritionists and having nutrition education actions shared and materials distributed, and presented a statistical difference from profile 2. These specific probability-based differences were observed for fresh foods.

Figure 1.

Association between canteen profiles and the criteria for choosing food sold in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe, 2024. (n=71).

Figure 1.

Association between canteen profiles and the criteria for choosing food sold in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe, 2024. (n=71).

Figure 2.

Association between canteen profiles and number of customers and foods by processing level that are sold in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe. 2024. (n=71).

Figure 2.

Association between canteen profiles and number of customers and foods by processing level that are sold in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe. 2024. (n=71).

4. Discussion

The Brazilian Dietary Guidelines advises that the diet should be predominantly composed of fresh and minimally processed foods, with limits consumption of processed foods and that UPFs should be avoided [

1]. This recommendation is strongly related to the prevention of an obesogenic food environment in school canteens. To this end, changes must be made to the supply and availability of food. It is possible and recommended to replace UPFs with culinary preparations, such as replacing industrialized juice and soda with natural fruit juice, and baked cakes instead of packaged snacks and sweets made in the canteens themselves. When these preparations combine fresh, minimally processed foods, and culinary ingredients (oils, sugar and salt), they are healthier, more economical, sustainable and in line with food culture [

1].

A high availability of UPFs was observed among the foods sold in the evaluated sample (

Table 2). This result was similar to that found in the evaluation of 19 state public school canteens in Aracaju in 2017 [

14], and to the findings of other studies in Brazilian states, which showed high sales of processed foods and UPFs in school canteens [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. These foods are related to the increased incidence of chronic diseases which are frequently observed in adults and older adults, and with an increase in young people [

1].

Providing quality food is essential for students to make good food choices. In the case of the sample evaluated, a small percentage of schools (32.4%) responded that the menu choice was based on state legislation, Law #8178-A, which prohibits the sale of foods that negatively affect the prevalence of childhood obesity, and provides that this commercialization meets the nutritional quality necessary to maintain the health of students [

30]. This result demonstrates a probable lack of knowledge about the existence and importance of legislation for the school community. It is worth mentioning that there was a statistically significant association between the presence of a nutritionist and the criterion for choosing the menu based on legislation (p=0.022). Regarding the association with the amount of UPFs, no statistical significance was found with the menu prepared by this professional (p=0.410).

Congruent with this, research carried out with data from the Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (

Estudo dos Riscos Cardiovasculares em Adolescentes – Erica) showed an association between schools that follow the laws that regulate food marketing, restricting the sale of food and drinks, and a lower chance of obesity in children and adolescents enrolled in public and private schools. This study also points out the need for the country to establish national regulations regarding the sale of food in school canteens, which goes further and improves local instruments so that they become clearer and more efficient [

31].

It was observed that the administration forms were almost proportional, with a slight inclination towards canteens administered by self-management. According to Wognski et al. [

23], schools with self-managed canteens prioritize offering healthier foods with better nutritional value due to greater concern for the well-being and development of students, but to the detriment of profit. On the contrary, profit is often prioritized in canteens with outsourced management due to the low level of interference from the school community (management and parents), with the consequent commercialization of more practical and caloric foods. However, regardless of management, some studies state that private schools are more likely to sell unhealthy foods when compared to public schools [

32,

33,

34].

Einloft

et al. [

35] assert that students’ food choices are related to autonomy and empowering behavior, which is important for this stage of life. However, when they have financial resources to purchase food, those chosen are generally UPFs with high energy density, such as cookies, candies and soft drinks [

23,

24,

25,

26]. These foods are hyperpalatable, can compromise the feeling of satiety and cause an addictive relationship [

36]. Furthermore, greater exposure to UPFs is associated with adverse health effects, mainly cardiometabolic and mental disorders and mortality [

37].

With regard to public schools in Brazil, the existence of

PNAE, which is the largest and most comprehensive school feeding program in the world, meets the needs of students, exclusively offering adequate and healthy food [

8,

38]. However, the marketing of food in private schools is the responsibility of their managers, who as a rule, tend to prioritize profit over the nutritional quality of the food, offering low quality food [

23]. This scenario is also in line with Decree #11,821 [

10] of the federal government, which has the prioritization of fresh and minimally processed foods in the sale of food and drinks in the school environment as one of its guidelines.

The development of nutrition education actions, as well as implementation of the good practices’ manual, specific assistance to schoolchildren with associated illnesses and disabilities, and the development of menus in these locations, is the responsibility of the local nutritionist [

39,

40]. In this study, more than half of the school canteens evaluated did not have a nutritionist (57.7%), and only 43.7% followed the menu prepared by this professional. Although the presence of nutritionists was scarce, the availability of nutritional information about food, the occurrence of nutrition education actions and educational materials on healthy eating were more prevalent in schools where the professional was present, especially regarding to the availability of nutritional information about food (p<0.001) and educational materials on healthy eating (p=0.038).

Healthier food choices promote a feeling of self-care and promote autonomous and voluntary practice of habits. In this process of strengthening autonomy to make choices, nutrition education actions, the principles of autonomy and self-care aim to make people agents of their own health through the creation of skills and absorption of knowledge necessary for healthy food choices.

It is important to highlight some limitations that were observed in the study, such as the lack of food pricing in canteens in this capital city, which is essential information to understand the influence that value has on students’ food choices and eating behavior. However, with the data obtained it is possible to observe the pattern of food trade in private schools in Aracaju, and thus envisage new actions and research to delve deeper into the topic in order to improve the food environment in schools. It is also recommended that research be carried out to directly evaluate the food consumption of schoolchildren.

5. Conclusions

It was observed that the sale of food in the canteens of private schools in Aracaju is inadequate from using the Brazilian Dietary Guidelines and current state legislation as an analysis parameter. There is a clear need to create public policies with the aim of promoting a healthier food environment in schools, with an emphasis on food sales. Nutrition education actions are essential for disseminating knowledge to the school community, allowing students greater autonomy in relation to good food choices. Stricter control over compliance with state legislation that regulates school meals is also necessary, as well as the improvement of existing legislation. Furthermore, the importance of the presence of the nutritionist as responsible technician is highlighted to develop healthier menus with the purpose of contributing to the healthy eating behavior of students, meeting nutritional needs, and helping to prevent noncommunicable chronic diseases in schools.

Funding information

Funded by the Scientific Initiation Scholarship from the Federal University of Sergipe (PIA11318-2022), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq) and financial support from Tobacco Control Alliance – TCA Health Promotion (Aliança de Controle do Tabagismo – ACT Promoção da Saúde), the Brazilian Institute for Consumer Protection (Instituto de Defesa do Consumidor - Idec), Desiderata Institute, and Ibirapitanga Institute.

Ethics Statements

Approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Sergipe, under Opinion #5,531,874, and all participants signed the free and informed consent form.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available to anyone for further analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Guia alimentar para população brasileira. Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, 2014.

- Henriques, P.; Alvarenga, C.R.T.D.; Ferreira, D.M.; Dias, P.C.; Soares, D.D.S.B.; Barbosa, R.M.S.; Burlandy, L. Ambiente alimentar do entorno de escolas públicas e privadas: oportunidade ou desafio para alimentação saudável? Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva. 2021, 26, 3135–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Desiderata. Guia prático para a cantina saudável. Instituto Desiderata, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, GEPPAAS, Eds: Instituto Desiderata: Belo Horizonte 2023.

- Brasil, Ministério da Saúde; Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais; Universidade Federal de Sergipe; Universidade Federal de Santa Maria. Cantina escolar saudável: promoção da alimentação adequada e saudável nas cantinas escolares, Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, 2024.

- 5. FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization. School Food and Nutrition Framework. FAO.

- Reed, S.F.; Viola, J.J.; Lynch, K. School and Community-Based Childhood Obesity: Implications for Policy and Practice. J Prev Interv Community. 2014, 42, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, G.M.; Cunha, T.C. de O. A importância da alimentação saudável para o desenvolvimento humano. POHSA. 2020, 10, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixinho, A.M.L. A trajetória do Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar no período de 2003-2010: relato do gestor nacional. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva. 2013, 18, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria No 1.010, de 08 de maio de 2006. Institui as diretrizes para a promoção da alimentação saudável nas escolas de educação infantil, fundamental e nível médio das redes públicas e privadas, em âmbito nacional. 2006.

- Brasil. Decreto no 11.821, de 12 de dezembro de 2023. Dispõe sobre os princípios, os objetivos, os eixos estratégicos e as diretrizes que orientam as ações de promoção da alimentação adequada e saudável no ambiente escolar. 2023.

- IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; Coordenação de População e Indicadores Sociais. Pesquisa nacional de saúde do escolar: análise de indicadores comparáveis dos escolares do 9o ano do ensino fundamental municípios das capitais: 2009/2019; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro 2022.

- Giesta, J.M.; Zoche, E.; Corrêa, R. da S.; Bosa, V.L. Fatores associados à introdução precoce de alimentos ultraprocessados na alimentação de crianças menores de dois anos. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva. 2019, 24, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagundes, A.; Gabriel, C.G.; Mendonça, I. de A. Cardápios das escolas públicas municipais de Aracaju, Sergipe. Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional 2018, 25, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.F. dos; Fagundes, A.A.; Gabriel, C.G. Caracterização das cantinas comerciais de escolas estaduais no município de Aracaju, Sergipe. Revista Baiana de Saúde Pública, 2017; 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística Aracaju (SE) | Cidades e Estados | IBGE: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/se/aracaju.html. (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Brasil, Ministério da Educação. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Censo Escolar 2021: Divulgação dos Resultados, Ministério da Educação: Brasília 2022.

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis; John Wiley & Sons,: New York 2002.

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple Comparisons Using Rank Sums. Technometrics 1964, 6, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, S.; Jr, N.J.C. Estatística não-paramétrica para ciências do comportamento, 2o edição., Porto Alegre: Artmed 2017.

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing.; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wognski, A.C.P.; Ponchek, V.L.; Schueda Dibas, E.E.; Orso, M.D.R.; Vieira, L.P.; Ferreira, B.G.C.S.; Mezzomo, T.R.; Stangarlin-Fiori, L. Comercialização de alimentos em cantinas no âmbito escolar. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2019, 22, e2018198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, J.D.L.; Mendes, L.L. Comercialização de lanches e bebidas em escolas públicas: análise de uma regulamentação estadual. DEMETRA: Alimentação, Nutrição & Saúde 2016, 11, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, F.; Marais, M.; Koen, N. The Provision of Healthy Food in a School Tuck Shop: Does It Influence Primary-School Students’ Perceptions, Attitudes and Behaviours towards Healthy Eating? Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre, T. de O.; Paini, D.; Bauermann, C.C.; Bohrer, C.T.; Kirsten, V.R. Alimentos vendidos em escolas e no seu entorno: uma análise do acesso e da qualidade dos alimentos no ambiente escolar. Saúde (Santa Maria). [CrossRef]

- Balestrin, M.; Brasil, C.C.B.; Kirsten, V.R.; Wagner, M.B. Cantinas escolares saudáveis no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil: diagnóstico e adequação à legislação. DEMETRA: Alimentação, Nutrição & Saúde 2022, 17, e63179–e63179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.O.; Höfelmann, D.A. Cantinas de escolas estaduais de Curitiba/PR, Brasil: adequação à lei de regulamentação de oferta de alimentos. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva. 2019, 24, 3805–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomelli, S. de C.; Londero, A. de M.; Benedetti, F.J.; Saccol, A.L. de F. Comércio informal e formal de alimentos no âmbito escolar de um município da região central do Rio Grande do Sul. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2017, 20, e2016136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Lei No 8178-A de 21/12/2016. Proíbe a comercialização de produtos que colaborem para a obesidade infantil em cantinas e similares, instalados em escolas públicas e privadas situadas em todo o estado de Sergipe. 2017.

- Assis, M.M.; Pessoa, M.C.; Gratão, L.H.A.; do Carmo, A.S.; Jardim, M.Z.; Cunha, C. de F.; de Oliveira, T.R.P.R.; Rocha, L.L.; Silva, U.M.; Mendes, L.L. Are the laws restricting the sale of food and beverages in school cafeterias associated with obesity in adolescents in brazilian state capitals? Food Policy 2023, 114, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andretti, B.; Goldszmidt, R.B.; Andrade, E.B. How Changes in menu quality associate with subsequent expenditure on (un)healthy foods and beverages in school cafeterias: a three-year longitudinal study. Prev Med. 2021, 146, 106456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, P. Do Junk food bans in school really reduce childhood overweight? evidence from Brazil. Food Policy 2021, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, P.R.E.S.; Noll, M.; de Abreu, L.C.; Baracat, E.C.; Silveira, E.A.; Sorpreso, I.C.E. Ultra-processed food consumption by brazilian adolescents in cafeterias and school meals. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 7162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einloft, A.B. do N.; Cotta, R.M.M.; Araújo, R.M.A. Promoting a healthy diet in childhood: weaknesses in the context of Primary Health Care. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva. 2018, 23, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEC. Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor. Alimentação saudável nas escolas: guia para municípios, S: de Defesa do Consumidor, 2022.

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-Processed Food Exposure and Adverse Health Outcomes: Umbrella Review of Epidemiological Meta-Analyses. BMJ. 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FNDE. Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação. Nota Técnica No 2974175/2022/COSAN/CGPAE/DIRAE; Brasília. 2022.

- CFN. Conselho Federal de Nutrição. Resolução CFN n° 378. Dispõe sobre o registro e cadastro de pessoas jurídicas nos conselhos regionais de nutricionistas e dá outras providências. 2005.

- CFN. Conselho Federal de Nutrição. Resolução CFN n° 600 Dispõe sobre a definição das áreas de atuação do nutricionista e suas atribuições. 2018.

- Brasil, Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome. Marco de referência de educação alimentar e nutricional para as políticas públicas, Ministério da Cidadania: Brasília, 2012.

Table 1.

Characterization of canteens in the Private Food Sales survey in Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil, 2024. (n=71).

Table 1.

Characterization of canteens in the Private Food Sales survey in Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil, 2024. (n=71).

| Variables |

n |

% |

| Type of administration |

| Outsourced |

33 |

46.5 |

| Self-managed |

36 |

50.7 |

| Other |

2 |

2.8 |

| Meals offered in the canteen |

| Breakfast |

3 |

4.2 |

| Lunch |

9 |

12.7 |

| Snacks |

71 |

100.0 |

| Dinner |

1 |

1.4 |

| Presence of nutritionist |

30 |

42.3 |

| Criteria for choosing the foods sold |

| Student preference |

65 |

91.5 |

| Possibility of production or acquisition |

36 |

50.7 |

| Best-selling foods |

55 |

77.5 |

| Higher profit percentage |

43 |

60.6 |

| Recommendation of the school |

44 |

62.0 |

| Nutritionist’s menu |

31 |

43.7 |

| State/municipal legislation |

23 |

32.4 |

| Existence of educational material on healthy eating in the canteen |

7 |

9.9 |

| Responsible for preparing educational material |

| Canteen |

6 |

8.5 |

| Nutritionist |

3 |

4.2 |

| Direction |

2 |

2.8 |

| Students |

1 |

1.4 |

| Carrying out educational activities to encourage healthy eating |

8 |

11.8 |

| Food production site |

| Canteen |

40 |

56.3 |

| Employee’s house |

6 |

8.5 |

| Seller’s house |

11 |

15.5 |

| Factory/Production center |

49 |

69.0 |

| Features of food marketing |

| Nutritional information not available |

32 |

45.1 |

| Available in all preparations |

25 |

35.2 |

| Available in some preparations |

14 |

19.7 |

| Availability of special purpose foods* |

23 |

32.4 |

| Availability of table/counter for meals |

46 |

64.8 |

| Prohibition of the sale of any food/product |

15 |

21.1 |

| Combo offer (food and beverage) at a lower price |

5 |

7.0 |

| Food and beverage promotion |

9 |

12.7 |

| Selling food by others (students, teachers, parents) |

3 |

4.2 |

Table 2.

Types of food sold in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil, 2024. (n=71).

Table 2.

Types of food sold in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil, 2024. (n=71).

| Food classification |

n (%) |

| In natural or minimally processed |

|

|

5 types of food |

70 (98.6) |

|

6 types of food |

1 (1.4) |

| Processed |

|

|

5 types of food |

67 (94.4) |

|

6 types of food

|

4 (5.6) |

| Ultra-processed |

|

|

5 types of food

|

24 (33.8) |

|

6 types of food

|

47 (66.2) |

Table 3.

Association between the presence of a nutritionist in canteens and characteristics of food sales in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil, 2024. (n=71).

Table 3.

Association between the presence of a nutritionist in canteens and characteristics of food sales in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil, 2024. (n=71).

| Variables |

Presence of nutritionist |

P-value |

Yes

n (%) |

No

n (%) |

| Nutritional information available |

| Not available |

5 (16.1) |

27 (67.5) |

<0.001 |

| Available in all preparations |

16 (51.6) |

9 (22.5) |

| Available in part of preparations |

10 (32.3) |

4 (10.0) |

| Marketing of foods for special purposes |

| Yes

|

14 (45.2) |

9 (22.5) |

0.072 |

| No

|

17 (54.8) |

31 (77.5) |

|

| Availability of table/counter for meals |

| Yes

|

20 (64.5) |

26 (65.0) |

0.581 |

| No

|

11 (35.5) |

14 (35.0) |

|

| Food choice criteria based on state/municipal legislation |

| Yes

|

15 (48.4) |

8 (20.0) |

0.022 |

| No

|

16 (51.6) |

32 (80.0) |

| Educational action to encourage healthy eating |

| Yes

|

6 (19.2) |

2 (5.0) |

0.072 |

| No

|

25 (80.6) |

38 (95.0) |

|

| Existence of educational material on healthy eating in the canteen |

| Yes

|

6 (19.4) |

1 (2.5) |

0.038 |

| No

|

25 (80.6) |

39 (97.5) |

|

| Prohibition of the sale of any food/product |

| Yes

|

5 (16.7) |

10 (25.0) |

0.558 |

| No

|

25 (83.3) |

30 (75.0) |

|

| Combo offer (food and beverage) at a lower price |

| Yes

|

2 (6.5) |

3 (7.5) |

1.000 |

| No

|

29 (93.5) |

37 (92.5) |

|

|

Food andbeveragepromotion

|

| Yes

|

5 (16.1) |

4 (10.0) |

0.490 |

| No

|

26 (83.9) |

36 (90.0) |

|

| Selling food by others (students, teachers, parents) |

| Yes

|

2 (6.5) |

1 (2.5) |

0.577 |

| No

|

29 (93.5) |

39 (97.5) |

|

Table 4.

Association between the amount of ultra-processed foods and the criteria for choosing foods sold in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil, 2024. (n=71).

Table 4.

Association between the amount of ultra-processed foods and the criteria for choosing foods sold in private schools in Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil, 2024. (n=71).

| Variable |

Ultra-processed foods |

P-value |

5

n (%) |

n (%) |

| Student preference |

| Yes

|

18 (75.0) |

47 (100.0) |

<0.001 |

| No

|

6 (25.0) |

0 |

|

| Best-selling foods |

| Yes

|

12 (50.0) |

43 (91.5) |

<0.001 |

| No

|

12 (50.0) |

4 (8.5) |

|

| Possibility of production or acquisition |

| Yes

|

20 (83.3) |

16 (34.0) |

<0.001 |

| No

|

4 (16.7) |

31 (66.0) |

|

| Higher profit percentage |

| Yes

|

6 (25.0) |

37 (78.7) |

<0.001 |

| No

|

18 (75.0) |

10 (21.3) |

|

| School recommendation |

|

|

|

| Sim |

21 (87.5) |

23 (48.9) |

0.002 |

| Não |

3 (12.5) |

13 (51.1) |

|

| Nutritionist’s menu |

| Yes

|

13 (54.2) |

18 (38.3) |

0.410 |

| No

|

11 (45.8) |

29 (61.7) |

|

| State or municipal legislation |

| Yes

|

17 (70.8) |

6 (12.8) |

<0.001 |

| No

|

7 (29.2) |

41 (87.2) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).