1. Introduction

It is predicted that by 2050, due to the exponential increase in the world's population, the planet will need 70% more food, putting great pressure on limited natural resources and highlighting pre-existing problems linked to biodiversity loss [

1], greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [

2] and deforestation [

3,

4]. Insect production is the only source of protein production with a low impact on GHG emissions. Recourse to entomophagy would therefore be both ecologically and economically sustainable, given insects' high reproductive capacity, rich protein content and low CO2 emissions when raised [

5].

Interest in insect consumption by humans in Africa has long been emphasized. The earliest written source on the subject dates from 1656, and focuses on caterpillar consumption in Madagascar at that time [

6]. Several recent publications testify to the continuing importance of this practice. Thus, [

7] list in their bibliographic synthesis no less than 370 references relating to "Lepidopterophagy" in Africa. It is difficult to draw up an inventory of the taxa concerned, because in addition to the species duly determined. More than a hundred according to [

8], we still have to consider taxa known only by a vernacular name and whose appearance, according to the photos available, does not correspond to those of the species determined.

In his book "Les pygmées Aka et la forêt centrafricaine", Bahuchet discusses the quantity of caterpillars harvested in the rainy season. He specifies yields per hectare and their denomination [

9]. As for Roulon-Doko, in her work entitled "Hunting, gathering and cultivation among the Gbaya of Central Africa", she develops the subject of caterpillar collecting and, in particular, the naming of 82 caterpillars, detailing the corpus concerning these names [

10].

The importance of local knowledge in the identification of taxa was highlighted a long time ago [

11]. Taking local names into account in such research is a self-evident step, as it constitutes the royal way of valorizing age-old empirical knowledge on the one hand, and the endogenous conception of the subject treated on the other. What's more, the association of these local names with the corresponding scientific name is essential, enabling this knowledge to be standardized and exploited on a larger scale, for example to identify the consumption zones of the same caterpillar around the world. This approach, which we will adopt here, comes under the heading of ethnoscience, defined by the LAROUSSE dictionary as "the branch of ethnology that studies the concepts and classification systems that each society develops to understand nature and the world".

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), many households in peri-urban areas are seeing their livelihoods threatened by the loss of biological diversity [

12]. Wildlife is scarce, crops are becoming less and less yielding, and so on [

12]. The main cause is the over-exploitation of natural resources, sometimes using devastating techniques, to improve livelihoods and meet the needs of the (urban) market by increasing production. As far as entomophagy is concerned, insects play an important role in the dietary traditions of tropical populations. Their diversity is high, and caterpillars play an important role [

13,

14]. This is particularly the case in Africa, where they occupy first place [

15] and especially in the Democratic Republic of Congo [

8,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, there are many territories/cities in this country for which no information is currently available. This is particularly the case of Kinshasa, which was the subject of a first brief study recently [

23] and which we propose to study in depth.

Kinshasa is experiencing a change in the dietary habits of its population. Insect consumption is one of the new dietary habits [

5]. However, over the years, the population has reported a decline in the availability of caterpillars and crickets, which they often consume. This decline calls for special research to establish a balance between species diversity and/or abundance of edible insects and entomophagy. This is the reason for our commitment to undertake this study to assess the relationship between humans and edible insects in Kinshasa. More specifically: (i) to assess the diversity of edible insects in Kinshasa and (ii) to evaluate the relationship between human-edible insects and entomophagy in Kinshasa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Presentation of the Study Area

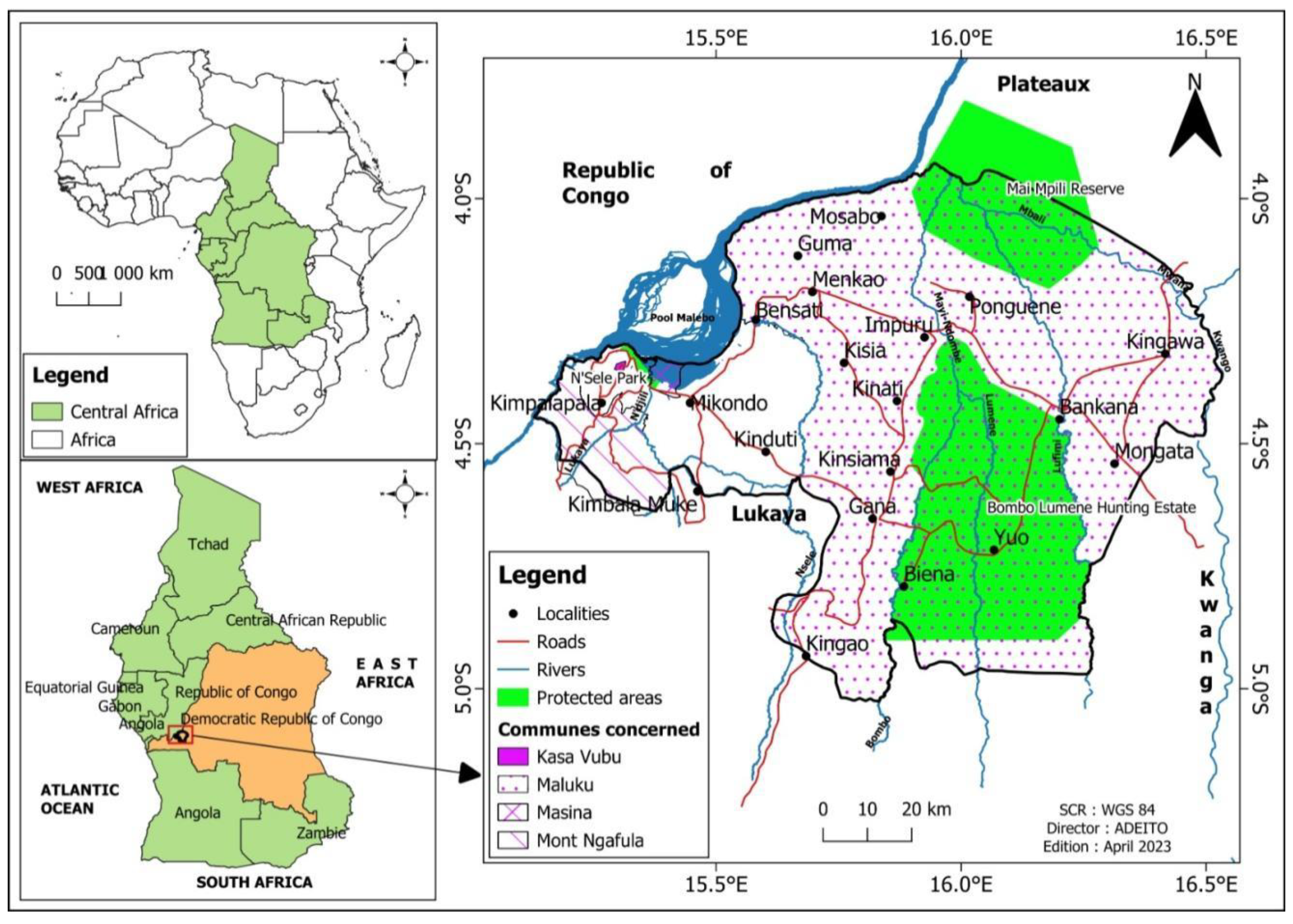

The City-Province of Kinshasa covers an area of 9 965 km

2 [

24]. It stretches along the southern bank of the "Pool Malebo", forming a huge crescent covering a low, flat surface with an average altitude of around 300 m. Located between 4° and 5° south latitude and between 15° and 16°32' east longitude (

Figure 1). Kinshasa is bordered to the east by the provinces of Mai-Ndombe, Kwilu and Kwango; to the west and north by the Congo River, forming a natural border with the Republic of Congo; and to the south by the province of Kongo Central [

25]. The climate is tropical, hot and humid. The average annual temperature is 25°C and average annual rainfall is 1,400 mm, with an average of 112 rainy days per year, peaking in April with 18 rainy days [

26]. Vegetation used to consist of Guinean-Congolian ombrophilous gallery forests in the wet valleys and grassy formations, but is now characterised by heavily degraded, intensively exploited pre-forest fallows in the form of forest recruits of various ages. In addition, a small group of typically ruderal vegetation grows along a strip a few metres wide along the railroad [

27].

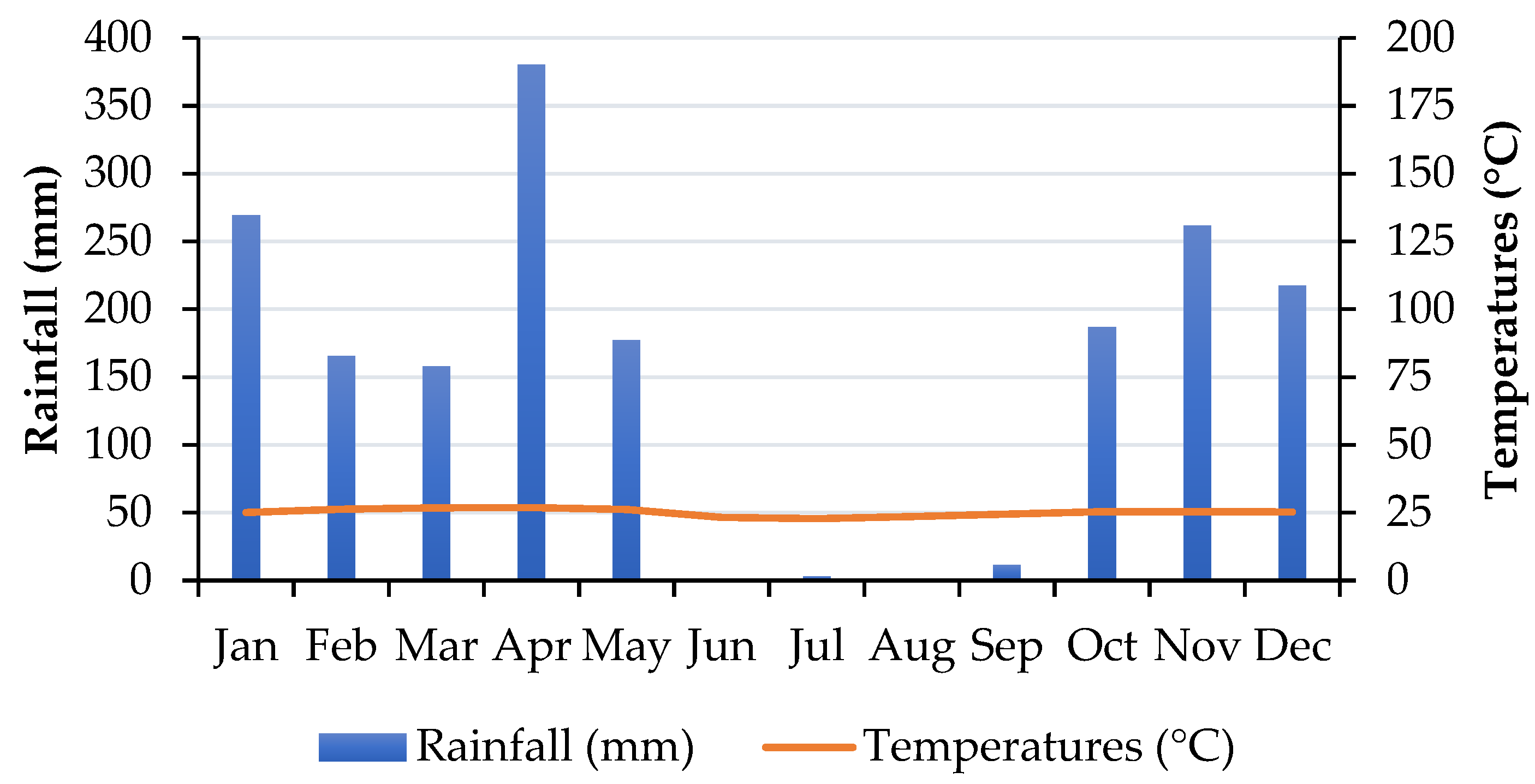

It rains in Kinshasa on average 112 days a year, with a peak of 18 rainy days in April. The city has a unimodal rainfall pattern, with a rainy season and a dry season (

Figure 2). The rainy season extends from mid-September to mid-May, with peaks of heavy rainfall in November and April. The relatively short dry season runs from mid-May to mid-September. The average relative humidity is 79% [

26].

2.2. Collect and Data Analysis

Four communes (Maluku, Mont-Ngafula, Masina and Kasa Vubu) were the target of this study on the basis of their geographical position, the availability of peri-urban ecosystems and the possibility of supplying edible insects. Pre-survey and survey sampling was random and purposive. Pre-surveys were carried out with a sample of four well-targeted people (non-timber forest product (NTFP) warehouse manager, head of household, restaurant manager and head of the environment department) per commune, i.e. a total of 16 pre-surveyed people, aged 45 or over, with at least 25 years' service/residence in the commune. These semi-selective criteria for respondents and pre-respondents would guarantee that information would be available in the area over a long period. In this pre-survey phase, the key questions concerned the diversity of edible insects in the area and entomophagy.

This was followed by an actual survey using a pre-established questionnaire. These included 30 heads of households, 30 restaurant managers and 30 edible insect sellers per commune. The respondents identified were aged 45 or over, had been in the profession for at least 25 years and had lived in the region for at least 25 years. A total of 360 people were surveyed to identify the insect species consumed in Kinshasa, the ecosystems that provide them (types of habitat/plant formations), their place of origin (province/city), the preference of species consumed in relation to ethnolinguistic groups, in relation to churches (religious denomination) and the frequency of their consumption by commune (administered by a survey form). Insect species cited/enumerated in French or local languages during the surveys were given their scientific names following the work of [

28,

29,

30].

All these data were entered and processed in Excel spreadsheets and R3.6.3 software, which made it possible to discriminate the three most consumed insect species (based on the formula: % = n/N * 100) in Kinshasa, their places of origin or supply, their habitat types, and other supplementary information [

31].

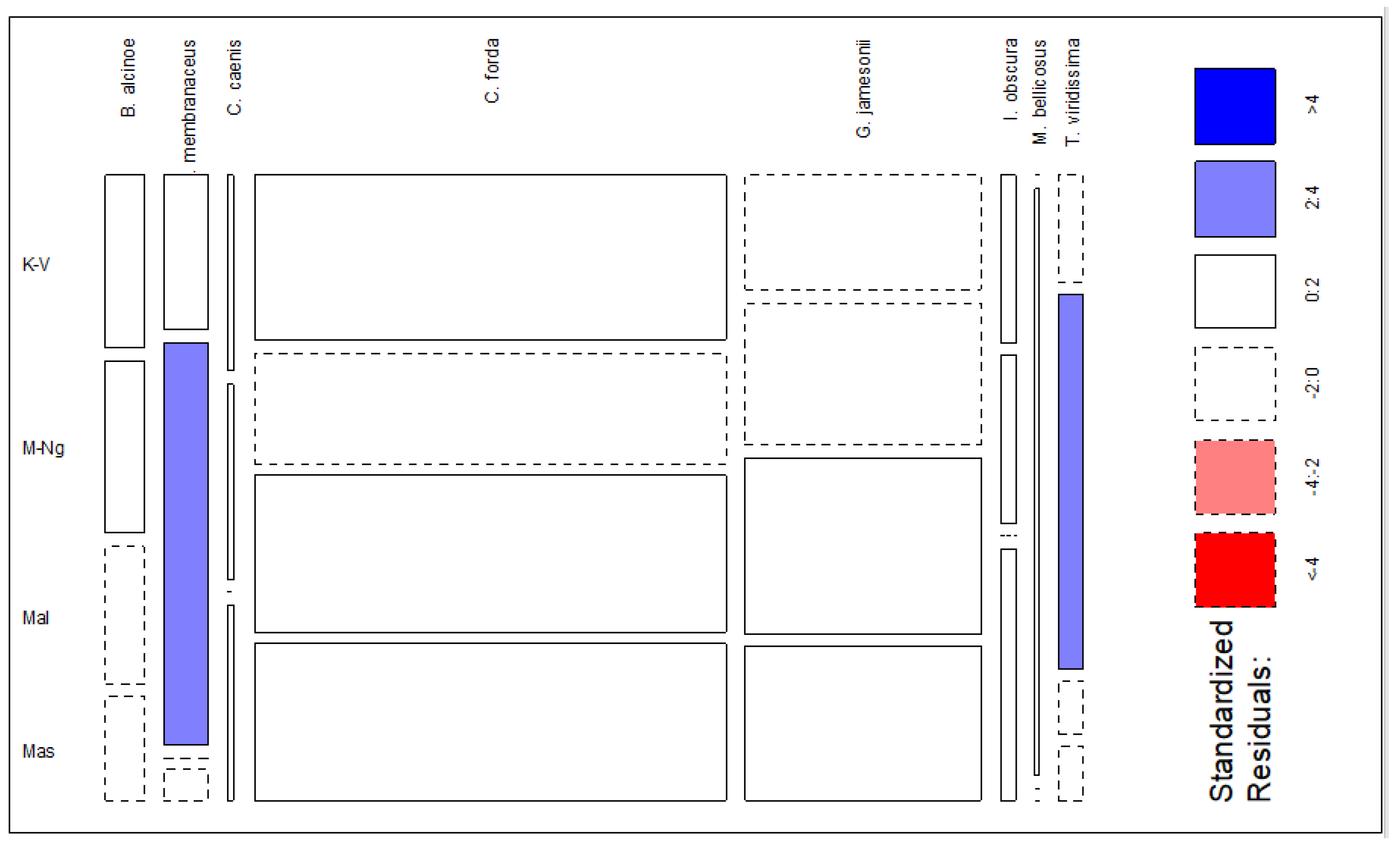

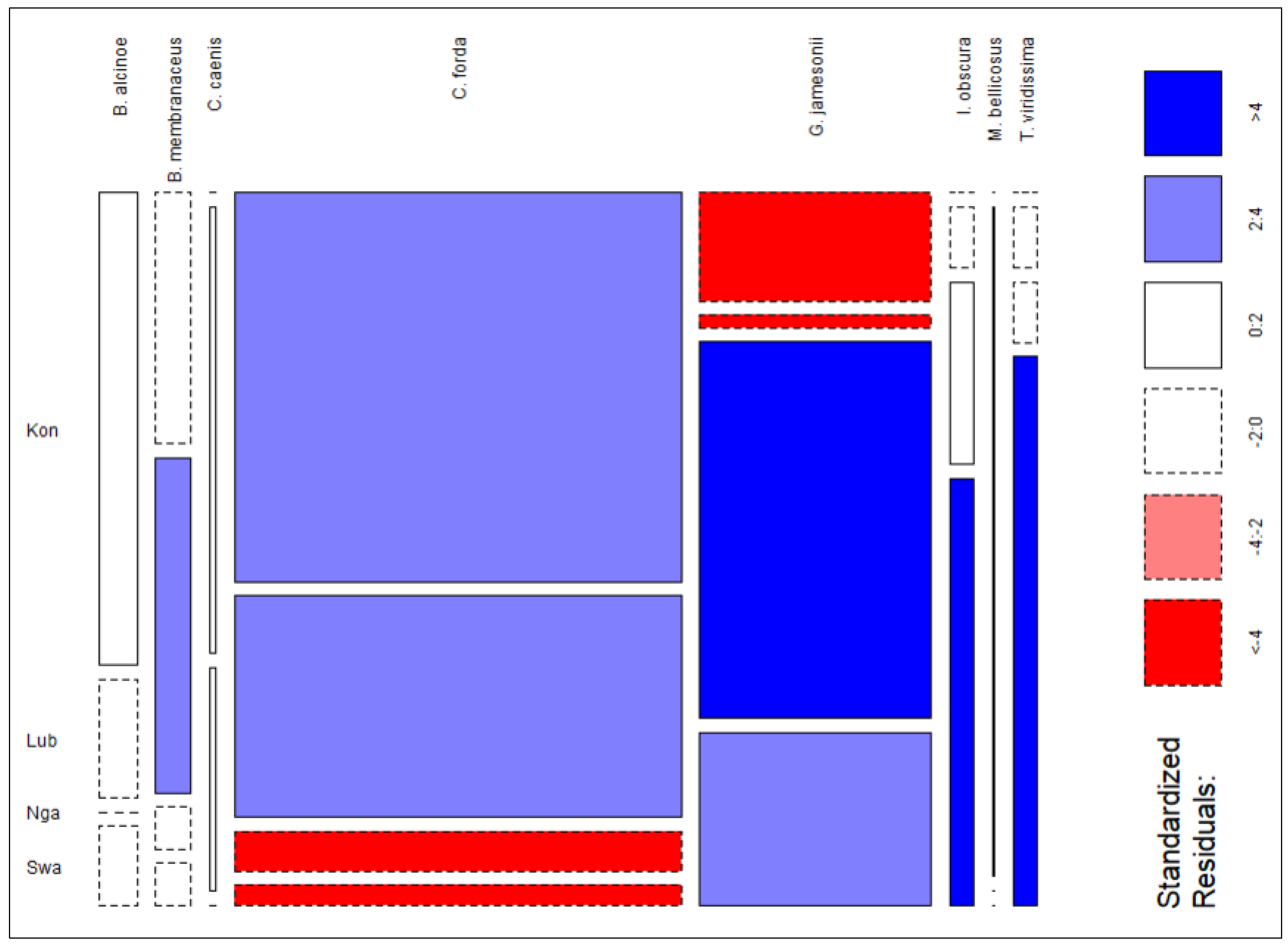

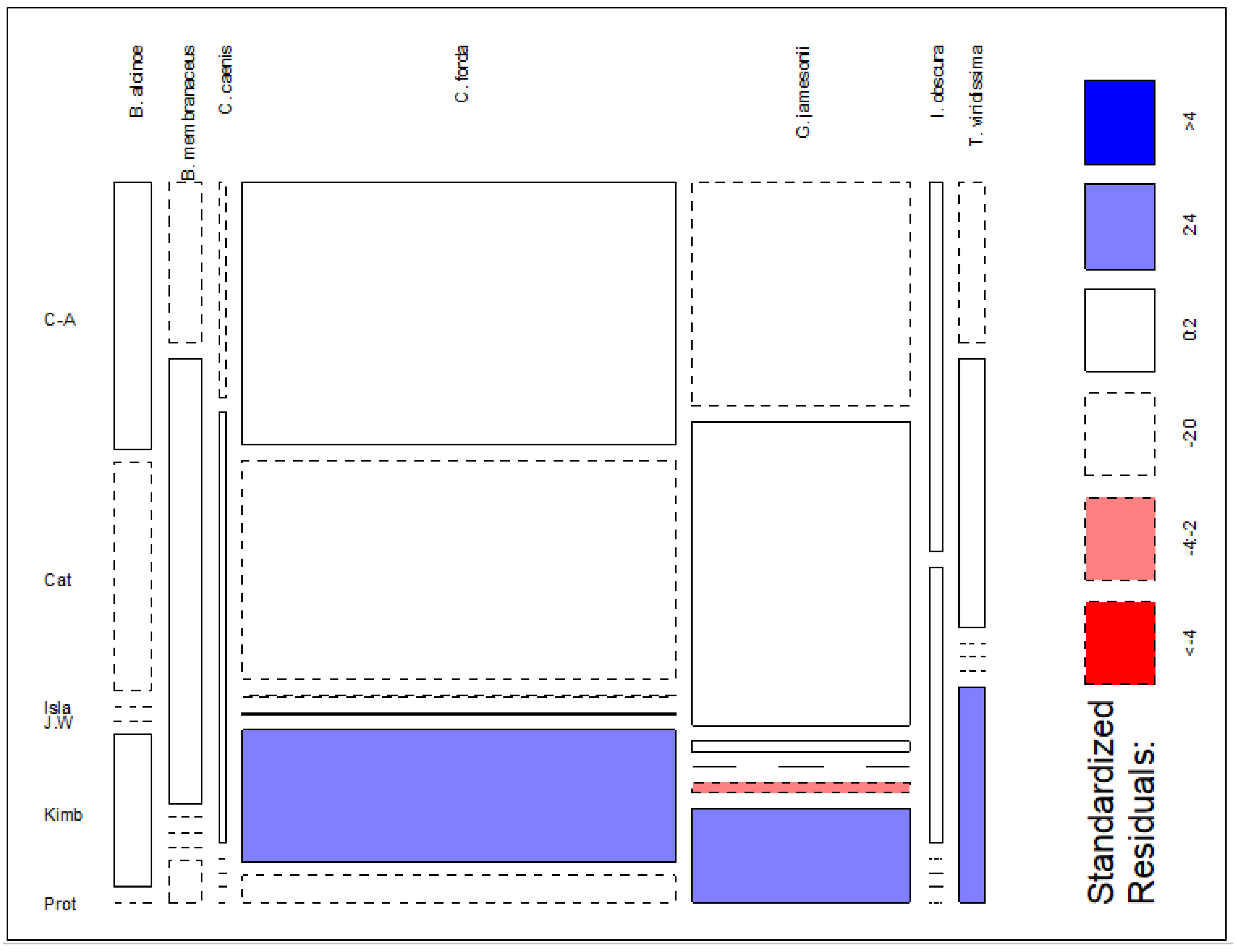

R software was used to express the relationship between communes and species consumed, ethnic groups and insect species consumed; and between churches and species consumed. Each rectangle in the graphs represented a table cell. Its width corresponds to the proportion of species consumed, represented in columns. Its height corresponds to the proportion of consumption by commune, ethnic group or religion. Finally, the color of the cell corresponds to the residual of the corresponding "k²" test: red cells are under-represented, blue cells are over-represented, and white cells are close to the expected numbers under the hypothesis of independence.

3. Results

3.1. Diversity of Edible Insects in Kinshasa

In Kinshasa, nine (9) species of insects are consumed and sold. These are:

Gonimbrasia jamesonii (Druce),

Cirina forda (Westwood),

Brachytrupes membranaceus (Drury),

Macrotermes bellicosus (Smeathman),

Cymothoe caenis (Drury),

Imbrasia obscura (Butler),

Bunaea alcinoe (Stoll),

Teigonia viridissima (Linnaeus) and

Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier). Three of these species are the most popular, namely:

G. jamesonii (28%)

, C. forda (27%) et

B. membranaceus (18%) (

Figure 3).

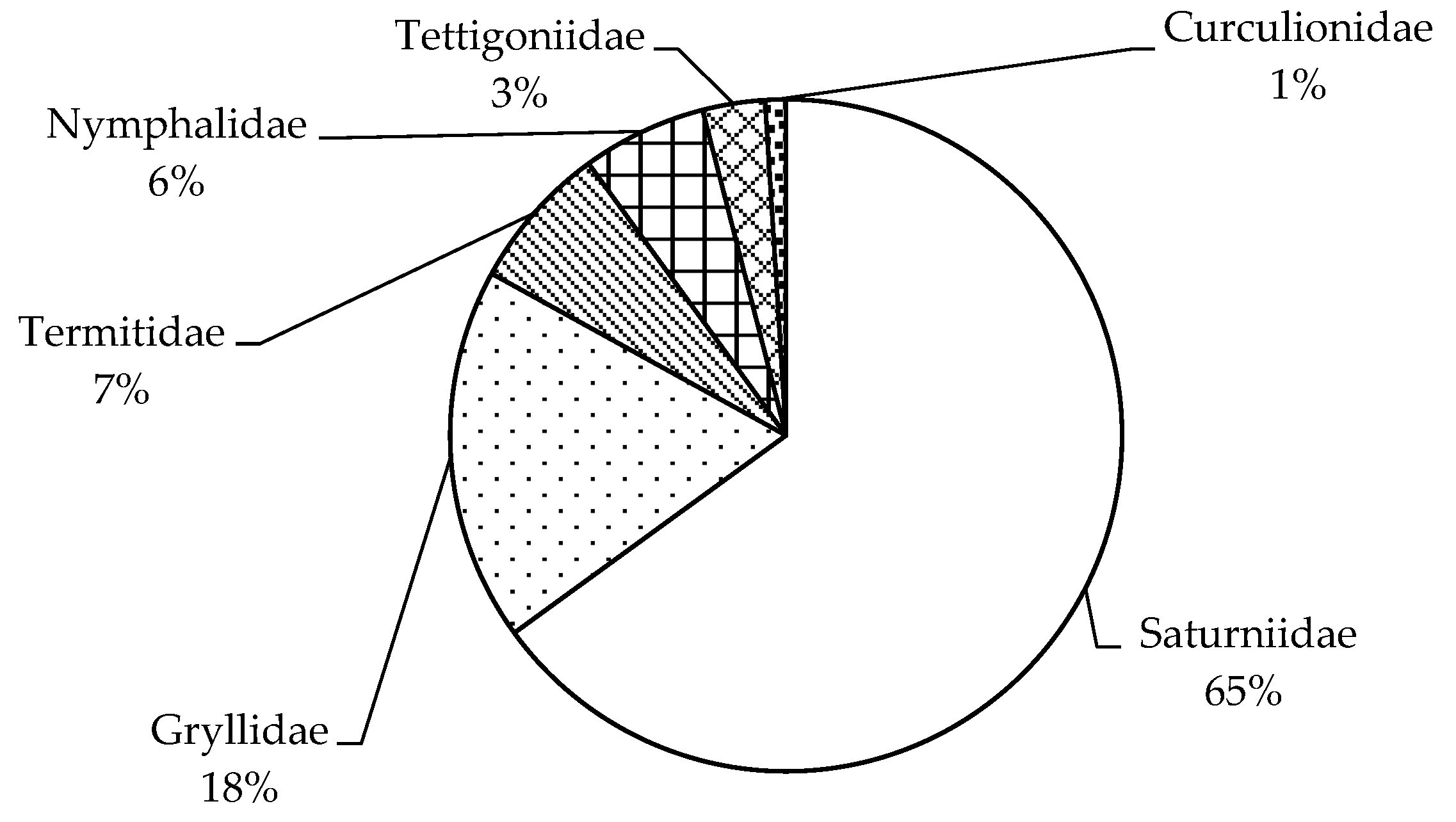

The various families most represented among the insect species identified are those of : Saturniidae (65%), Gryllidae (18%), Termitidae (7%), Nymphalidae (6%), Tettigoniidae (3%) and Curculionidae (1%); with a high dominance of Saturnuudae compared to other identified families (

Figure 4).

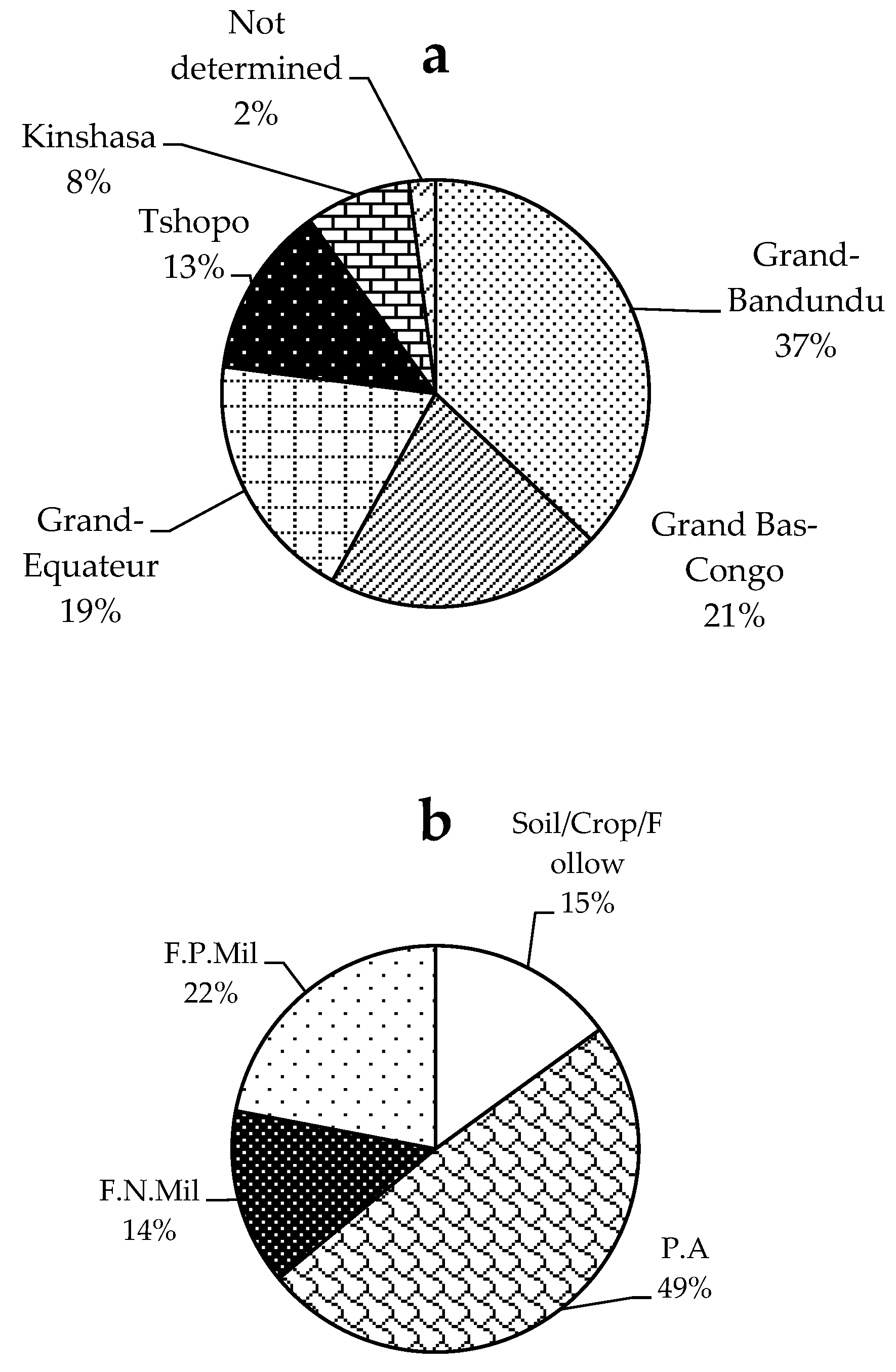

The most widely consumed insects come from five localities (provinces) bordering and surrounding Kinshasa. The province of Grand Bandundu is the main supply point (37%), followed by Grand Bas-Congo (21%), Grand Equateur (19%), the province of Tshopo (13%), 8% exclusively in the periphery of Kinshasa and 2% from undetermined areas (

Figure 5a). The ecosystems providing edible insects in the Kinshasa periphery are:

Acacia plantations (49%), planted

Millettia forests (22%), natural

Millettia forests (14%) and soil/field/ fallow land (15%) (

Figure 5b). Forest ecosystems (woodland formations) are dominated mainly by

A. auriculiformis and

M. laurentii in

Acacia plantations and

Millettia stands respectively.

3.2. Entomophagy in Kinshasa

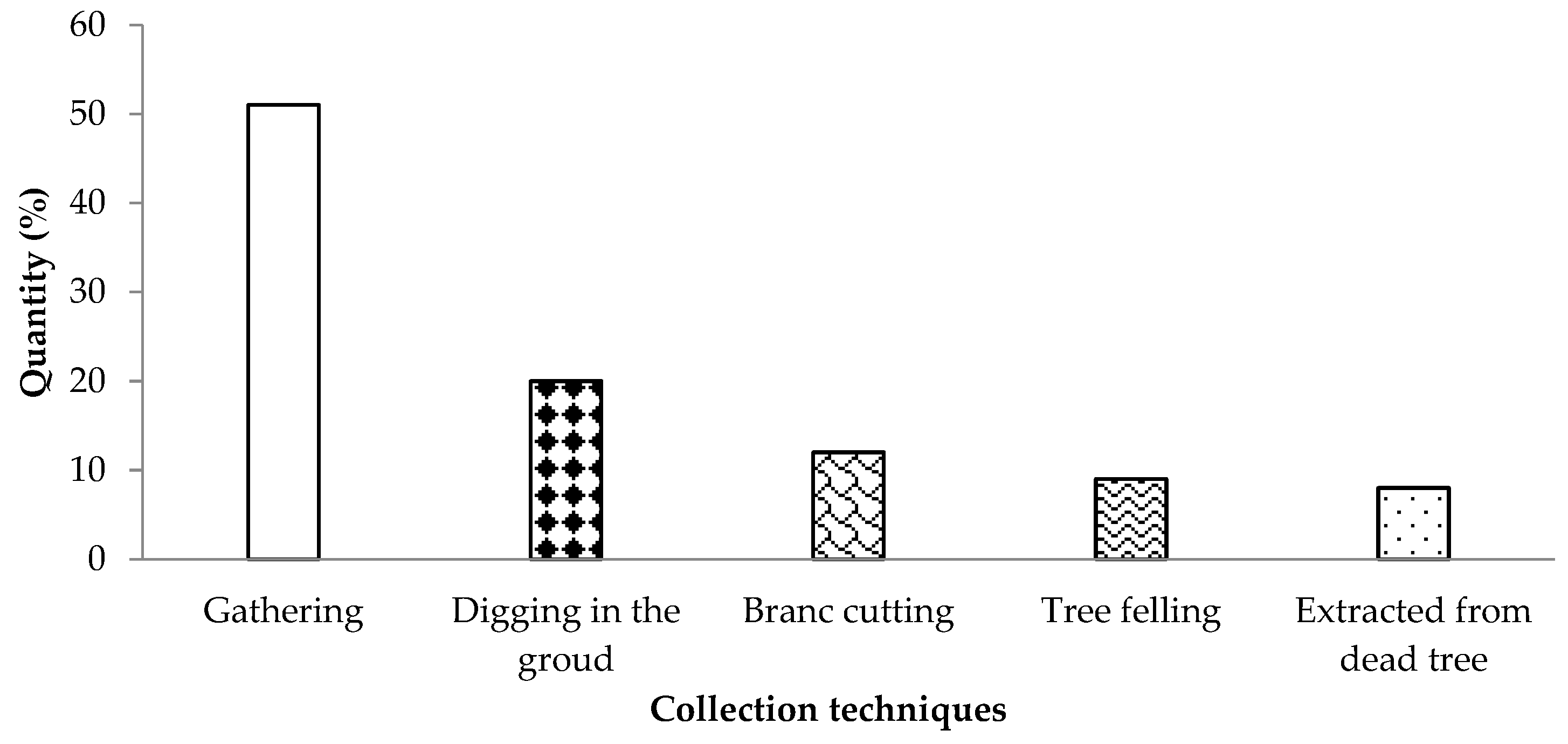

The

Figure 6 below shows the different techniques used to collect edible insects in Kinshasa: 50% of insects are collected by gathering, 20% by digging in the ground, 12% by cutting tree branches, 9% by tree felling and 8% by extracting them from dead trees.

3.2.1. Entomophagy by Ethnolinguistic Group and Church

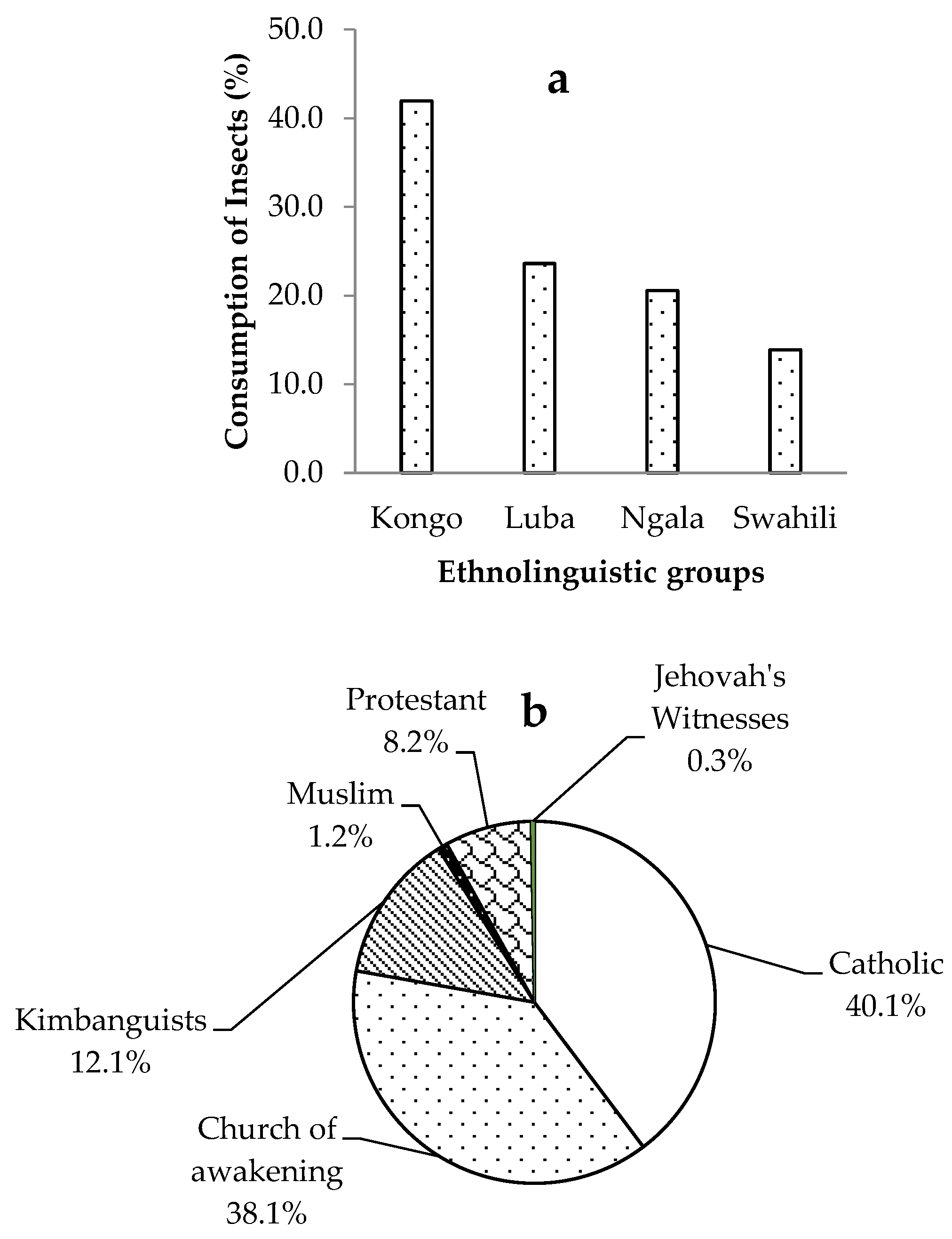

Figure 7a shows that Kongo is the ethnolinguistic group with the highest insect consumption (41.9%), followed by Luba (23.6%), Ngala (20.6%) and Swahili (13.9%).

Figure 7b shows that insect consumers are more Catholic (40.1%), Church of awakening (38.1%), then Kimbanguists (12.1%), then Protestants (8%), Muslims (1.2%), and finally Jehovah's Witnesses.

3.2.2. Correlation between Communes and Species Consumed, Ethnolinguistic Groups and Species Consumed, Churches and Species Consumed, Household Size and Species Consumed

Figure 8 shows that people in the communes of Kassa Vubu (57%), Maluku (54%), Masina (54%) and Mont-Ngafula (39%) mainly consume

C. forda and

G. jamesonii. The proportion of C. forda consumed in the commune of Kasa Vubu (63.3%) is higher than in the other three communes studied. However, the proportion of

G. jamesonii consumed in the commune of Maluku (34.4%) is higher than in the other communes studied. With regard to

C. forda consumption by commune, there is no statistical difference between Kasa Vubu, Masina and Maluku (k

2 = -0.2), but these communes differ statistically from the commune of Mont-Ngafula (k

2 = -2.0). With regard to

G. jamesonii consumption, there is no statistical difference between the communes of Kasa Vubu and Mont-Ngafula (k

2 = -2.0); and no significant difference between Masina and Maluku (k

2 = -0.2).

The figure below shows the consumption/preference of insect species by ethnic group. It shows that the Luba (79%) and Kongo (78%) consume/prefer

C. forda; and that the Ngala (76%) and Swahili (52%) consume more

G. jamesonii (

Figure 9).

C. forda is consumed by 64% of the Kongo ethnolinguistic group and 36% of the Luba ethnolinguistic group. In contrast,

G. jamesonii is consumed by 59% of the Ngala ethnolinguistic group and 41% of the Swahili ethnolinguistic group. With regard to

C. forda consumption by ethnolinguistic groups, there is statistical equality between Kongo and Luba (k

2 = 2.4), but the latter differ from Swahili and Ngala (k

2 =-0.4). Regarding

G. jamesonii consumption, there is also no statistical difference between Luba and Kongo (k

2 = -0.4); but there is a statistical difference between Swahili (k

2 = 2.4) and Ngala (k

2 = >4).

Figure 10 shows that believers in the Catholic (39.7%), Church of awakening (38.1%), Kimbagu (13.3%), Islam (0.8%), Protestant (7.8%) and Johovah's Witness churches (0.3%) mainly consume

C. forda and

G. jamesonii. These two species are consumed respectively at 48.8% and 32.9% by Catholic believers, 59.9% and 26.3% by Revivalist churches, 87.5% and 4.2% by Kimbanguists, 33.3% and 66.7% by Muslims, 53.6% and 28.6% by Protestants and 100% of the

C. forda species by Jehovah's Witnesses. With regard to

C. forda consumption by church believers, there is statistical equality between the Catholic, Islamic and Protestant churches (k

2 = -2.0), between the Revivalist and Jehovah's Witness churches (k

2 = 0.2), and the Kimbangu church (k

2 = 2.4) differs from all the others. With regard to

G. jamesonii consumption, there is statistical equality between the Catholic and Islamic churches (k

2 = 0.2), between the Revivalist and Jehovah's Witness churches (k

2 = -2.0), and a statistical difference between Kimbagu (k

2 = [-4, -2]) and Protestant (k

2 = 2.4).

Table 1 shows the insect species most consumed in relation to the size of the households surveyed. It shows that

C. forda is the species most consumed/preferred in all households, whatever their size. The difference is statistically significant between the quantity of insect species consumed (p = 0.00871**) and the household size classes ([1-5], [6-10], [11-15] and [16-20]).

4. Discussion

4.1. Diversity of Edible Insects in Kinshasa

The result of this study inventoried 9 species of edible insects based on a survey of 360 respondents. The population is familiar with the region's edible insects. They identify them on the basis of morphological traits and not by their host plants/habitats or ecosystems [

15,

20]. Nine edible insect species were listed by the population for the purposes of this study. However, all nine were identified to species level. Latham's study of edible caterpillars and their food plants mentions nine caterpillar species consumed by the population of Bas-Congo, notably that of the Cataractes district [

31] and that of [

28] mentions four categories of caterpillars, including those identified in our study area In Kisangani, 14 species are consumed [

20]. Several of the local caterpillar species mentioned by interviewees were not found during field observations. This may be due to the fact that our survey period was not necessarily the period of appearance of all the species mentioned. Also, not all the species cited in our surveys appear at the same time of year.

In Central Africa, nearly 500 species of edible insects have been recorded. In southern Cameroon, for example, beetle species such as palm weevil larvae (Rhynchophorus sp.) and certain Lepidoptera species are highly prized, whereas in the north of the country, orthopterans (locusts and grasshoppers) and isopterans (termites) are preferred [

32]. It is therefore likely that entomophagy depends on the composition and structure of the local community of edible insects, which would be strongly linked to the characteristics of the environment. This result does not corroborate the findings of the present study, which showed low specific diversity but also a contradiction in terms of preference for consumption. It should be noted that this difference in specific diversity is due to the difference in surface areas considered in the two studies, but also to the difference in ecological zones considered (urban/peri-urban against rural/forest zones).

Edible insects are also of significant ecological interest, given the diversity of species consumed and the diversity of habitats they occupy [

33]. This result corroborates with the findings of this study, which counted 4 different ecosystems/habitats providing edible insects. This diversity of ecosystems/habitats providing (4) edible insects in the city of Kinshasa would be proportional to the diversity of insect species inventoried (9) in the area. Their importance is also illustrated by the increasing number of studies dealing with the subject and the growing worldwide repertoire (500 species listed in 1992 [

34], estimated at 2111 species in 2017 [

32]). However, these insect species are potentially threatened by anthropogenic factors, including overexploitation [

35].

4.2. Entomophagic Monodominance: The Case of C. forda in Kinshasa

In many countries around the world, entomophagy is a common practice rooted in tradition. Edible insects are an important source of protein, unsaturated fatty acids, minerals and numerous vitamins [

2,

24]. In addition, they are a substantial source of income, as they are sold in markets, supplementing household income (30 to 75% of household income) [

34].

For many city residents in Africa, caterpillars are a popular, even sought-after, foodstuff. The availability of caterpillars is seasonal, and their supply and marketing have attracted the attention of several researchers. The cities of Ibadan [

36,

37], Abidjan [

38], Yaoundé [

39], Lubumbashi [

40,

41], Harare [

42], Brazzaville [

43], Kisangani [

20], Bangui [

44], Ilorin [

45], Ndola [

46], Kikwit [

47], are good examples. These results support the findings of this study, which show that edible insect supply areas in urban areas (in the case of Kinshasa) are predominantly the nearby forest localities and a small proportion in the peripheries of these cities. The decline of the local economy, and the use of organic foods based on the abusive exploitation of natural capital, have led to new food practices in Kinshasa, including the collection and consumption of insects. Campeophagy is accentuated by media campaigns on the nutritional importance of caterpillars, their prescription in medical or nutritional prescriptions and cultural mixing [

28].

Very few studies have been carried out on edible insects in Central Africa at the urban level. The work of [

19,

20] specified a few edible species in the Kinsagani region and [

28] in the Luki reserve region, all located in secondary towns (in provinces/forest localities) in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The additional data provided by this study provide information on the reality of a main town with a high human density.

All ethnolinguistic groups living in Kinshasa have become "campeophages", and the number of actors belonging to groups originating from this area is significant. The study of [

15], reviewing the knowledge of ethnolinguistic groups practicing campéophagy in Africa, reports this practice among several ethnolinguistic groups in the DRC. However, the Kongo ethnolinguistic groups, originally part of the ethnic groups mentioned in our study area, are also included in these studies. Other ethnolinguistic groups found in Kinshasa are the Luba, the Ngala and the Swaahili, thus enriching information on the relationship between entomophagy and ethnolinguistic groups.

C. forda's preference for consumption by all the above-mentioned ethnolinguistic groups would be due to its availability and low purchase cost throughout the year [

28].

5. Conclusions

Insect consumption is attracting growing interest these days. In this study, we have shown that insect collecting and consumption in Kinshasa is a culturo-ethnic practice that concerns all stakeholders in the area. Many populations around the world consume insects. These facts, reported by various authors, are also confirmed in the case of Kinshasa.

The results of this study shed light on both the diversity of edible insects and their contribution to food security in Kinshasa. In the light of the surveys carried out and the analysis of the information gathered, we can conclude that:

- -

all nine insect species are consumed in Kinshasa, of which C. forda, G. jamesonii and B. membranaceus are the three best consumed, with Saturniidae as the best represented family;

- -

the supply of edible insects in Kinshasa is concentrated in the large provinces of Bandundu, Bas-Congo, Equateur, Tshopo and the periphery of Kinshasa;

- -

In Kinshasa, these insects are collected by gathering, digging underground, extracting from dead trees, cutting tree branches and felling trees.

- -

The Kongo linguistic group is the biggest consumer of these insects, and Catholic Christians are the biggest consumers of these insects as a church (religion).

- -

In all communes, all ethnic groups, all churches and all household size categories, C.forda is the most consumed species.

The results of this study contribute to a better understanding of the motivations of the population of Kinshasa with regard to insect consumption. The outlook for the future will be to provide a better framework for this sector, to envisage other types of valorization/processing of this foodstuff, to identify demand and to innovate. Indeed, it remains entirely possible to integrate insects into other types of products and/or to promote them in other ways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.M. and M.D.; methodology, C.A.M. and F.F.; software, M.K. and D.M.-e.B.: formal analysis, C.A.M..; investigation, C.A.M.; data curation, C.A.M.; writing original draft preparation, C.A.M.; writing review and editing, C.A.M., D.M.-e.B. and K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the World Bank through the Regional Center of Sustainable. Cities in Africa (CERViDA-DOUNEDON), Funding number IDA 5360 TG.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the World Bank and the University of Lomé. (UL) via the Regional Center of Excellence for Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERViDA-DOUNEDON) for their financial contribution and scientific supervision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Photos of the Three Most Commonly Consumed Insect Species in Kinshasa

References

- C. Bigard, B. Regnery, S. Pioch, and J. D. Thompson, “From theory to practice of the Avoid-Reduce-Compensate (ERC) sequence: avoid or legitimize biodiversity loss?,” Dév. Durable Territ. Économie Géographie Polit. Droit Sociol., vol. 11, no. 2, 2020, Accessed: Oct. 07, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://journals.openedition.org/developpementdurable/17488.

- B. Seguin and J.-F. Soussana, “Greenhouse gas emissions and climate change: causes and consequences observed for agriculture and livestock,” Courr. Environ. INRA, vol. 55, no. 55, pp. 79–91, 2008, Accessed: Oct. 07, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://hal.science/hal-01198631/.

- H. Aiking, “Future protein supply,” Trends Food Sci. Technol., vol. 22, no. 2–3, pp. 112–120, 2011, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092422441000107X.

- Van Huis, “Potential of Insects as Food and Feed in Assuring Food Security,” Annu. Rev. Entomol., vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 563–583, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Nsevolo, “‘Contribution to the study of entomophagy in Kinshasa’, Trav. Graduation Diploma,” Trav. Fin D’Etudes Diplôme, 2012.

- J. Kay, “Etienne de Flacourt, the history of the Grand Island of Madagascar (1658),” Curtiss Bot. Mag., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 251–257, 2004, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45065653.

- F. Malaisse and P. Latham, “Human consumption of Lepidoptera in Africa: an updated chronological list of references (370 quoted!) with their ethnozoological analysis,” Geo-Eco-Trop Rev. Int. Géologie Géographie DÉcologie Trop., vol. 38, no. 2, 2014, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/189275.

- L. Bocquet, “Nanofluidics coming of age,” Nat. Mater., vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 254–256, 2020, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41563-020-0625-8.

- S. Bahuchet, The Aka Pygmies and the Central African forest: ecological ethnology, vol. 1. Peeters Publishers, 1985. Accessed: Oct. 04, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=u7bfp-RDeSEC&oi=fnd&pg=PA2&dq=Bahuchet+Les+pygm%C3%A9es+Aka+et+la+for%C3%AAt+centrafricaine+&ots=RqnNGUuhQS&sig=X8hoFFx1Rs4Oh1glJW7XlhaOl0M.

- P. Roulon-Doko, “Hunting, gathering and cultivation among the Gbaya of Central Africa,” Chasse Cueillette Cult. Chez Gbaya Centrafrique, pp. 1–540, 1998.

- M. Berlin and L. J. Mester, “Debt covenants and renegotiation,” J. Financ. Intermediation, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 95–133, 1992, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/104295739290005X.

- Maindo, P. BAMBU, and A. Ntahobavuka, “Reconciling endogenous knowledge and livelihoods in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Une Strat. Gest. Durable Biodiversité Biol. Autour Kisangani Tropenbos RD Congo, 2017, Accessed: Oct. 07, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.tropenbos.org/file.php/2190/concilier-les-savoirs-endogenes-et-les-moyens-dexistence-en-rdc-low.pdf.

- J. Ramos-Elorduy, “Insects: A sustainable source of food?,” Ecol. Food Nutr., vol. 36, no. 2–4, pp. 247–276, Sep. 1997. [CrossRef]

- L. L. Boyombe et al., “Harvesting techniques and sustainable exploitation of edible caterpillars in the Yangambi region, DR Congo,” Geo-Eco-Trop, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 113–129, 2021, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.academia.edu/download/68265425/GET.45.1.10..pdf.

- F. Malaisse and P. Latham, “Human consumption of Lepidoptera in Africa: an updated chronological list of references (370 quoted!) with their ethnozoological analysis,” Geo-Eco-Trop Rev. Int. Géologie Géographie DÉcologie Trop., vol. 38, no. 2, 2014, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/189275.

- N. Leleup and H. Daems, “Kwango food caterpillars. Causes of their depletion and recommended measures to remedy it,” J. Tradit. Agric. Appl. Bot., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1–21, 1969, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.persee.fr/doc/jatba_0021-7662_1969_num_16_1_3015.

- M. Tango, Insects as human food. Zaïre, 1981.

- F. Malaisse and G. Lognay, “Edible caterpillars from tropical Africa,” Insectes Dans Tradit. Orale Leuven Peeters, pp. 279–304, 2003, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=2CUjBqvHEdIC&oi=fnd&pg=PA279&dq=MALAISSE+et+al.,+2003+&ots=4-cVUU903y&sig=Zk6m2ezmAfZ40i1QyUmyM3lq6uc.

- E. Okangola, “Contribution to the biological and ecological study of edible caterpillars in the Kisangani region,” Cas Réserve For. Yoko Ubundu RD Congo DEA Inéd Fac Sci Unikis 79p, 2007.

- J. Lisingo, J.-L. Wetsi, and H. Ntahobavuka, “Investigation of edible caterpillars and the various uses of their host plants in the districts of Kisangani and Tshopo (DR Congo),” Geo-Eco-Trop, vol. 34, no. 1–2, pp. 139–146, 2010, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Janvier-Lisingo-2/publication/295086294_Enquete_sur_les_chenilles_comestibles_et_les_divers_usages_de_leurs_plantes_hotes_dans_les_districts_de_Kisangani_et_de_la_Tshopo_RDCongo_Survey_on_the_edible_caterpillars_and_the_use_of_their_host_pl/links/56c74a3608aee3cee5394147/Enquete-sur-les-chenilles-comestibles-et-les-divers-usages-de-leurs-plantes-hotes-dans-les-districts-de-Kisangani-et-de-la-Tshopo-RDCongo-Survey-on-the-edible-caterpillars-and-the-use-of-their-host-pl.pdf.

- F. Malaisse, How to live and survive in Zambezian open forest (Miombo ecoregion). Presses agronomiques de Gembloux, 2010. Accessed: Sep. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=FcXW4MJUGYkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA7&dq=MALAISSE,+2010+&ots=8W7BhKKslQ&sig=MY40E6H-dRLkma6YKjYKvcB8qeo.

- J. Lisingo, F. Lokinda, J. L. Wetsi, and H. Ntahobavuka, “The artisanal exploitation of wood and edible caterpillars by the inhabitants of the city of Kisangani and its surroundings,” Benneker C Assumani -M Maindo Bola F Kimbuani G Lescuyer G Aléds Bois À L’ordre Jour Exploit. Artis. Bois D’øeuvre En RD Congo Sect. Porteur D’espoir Pour Dév. Petites Moy. Entrep. Wagening. Pays-Bas Tropenbos Int., pp. 248–262, 2012.

- C. Adeito Mavunda et al., “Kinshasa Province (Democratic Republic of Congo): Typology of Peri-Urban Ecosystems Providing Edible Insects,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 15, p. 11823, 2023.

- L. De Saint Moulin and T. Kalombo, Atlas of the administrative organization of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Cepas, 2005.

- C. A. Mavunda et al., “Spatio-temporal dynamics of land cover changes under anthropogenic impact in the city of Kinshasa (DRC) from 2001 to 2021,” Geo-Eco-Trop, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 137–148, 2022.

- S. S. Kinyamba, F. M. Nsenda, D. O. Nonga, T. M. Kaminar, and W. Mbalanda, Monograph of the city of Kinshasa. ICREDES, 2015.

- M. Habari, “Floristic, phytogeographical and phytosociological study of the vegetation of Kinshasa and the middle basins of the N’djili and N’sele rivers in DR Congo", PhD Thesis, Doctoral thesis, University of Kinshasa,” PhD Thesis, Doctoral thesis, University of Kinshasa, 2009.

- E. Lonpi Tipi et al., “Caterpillars consumed in the region of the Luki Biosphere Reserve in the Democratic Republic of Congo: actors, local knowledge and pressures,” BOIS FORETS Trop., vol. 355, pp. 21–34, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Franck, Capture, packaging, shipping, collection of insects and mites for identification. CIRAD, 2008. Accessed: Oct. 07, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/548605.

- G. Delvare and H.-P. Aberlenc, Insects from Africa and tropical America: keys to recognizing families. Editions Quae, 1989. Accessed: Oct. 07, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=Wrl61dIlJrAC&oi=fnd&pg=PA15&dq=identification+des+insectes%3B+afrique+centrale&ots=mNMCXED5b7&sig=isD2j6H9k6Y9enEQN7sL4c4I9bs.

- P. Latham, Edible caterpillars and their food plants in the province of Bas-Congo. Paul Latham, 2008. Accessed: Oct. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paul-Latham/publication/265381118_Les_chenilles_comestibles_et_leurs_plantes_nourricieres_dans_la_province_du_Bas-Congo/links/54103fa80cf2d8daaad2b829/Les-chenilles-comestibles-et-leurs-plantes-nourricieres-dans-la-province-du-Bas-Congo.pdf.

- P. Polepole, L. Laroumagne, F. J. Muafor, P. LeGall, and L. Brice, “Introducing edible insects into animal feed in Cameroon – a new opportunity?: Literature review”.

- P. Nsevolo, A. Taofic, R. Caparros, L. Sablon, É. Haubruge, and F. Francis, “Entomological biodiversity as a food source in Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo)”, in Annales de la Société entomologique de France,” in Annales de la Société entomologique de France (NS), Taylor & Francis, 2016, pp. 57–64.

- A. van Huis, “Insects eaten in Africa (Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Diptera, Heteroptera, Homoptera),” Ecol. Implic. Minilivestock N. H. USA Sci. Publ., pp. 231–244, 2005.

- G. R. DeFoliart, “An overview of the role of edible insects in preserving biodiversity,” Ecol. Food Nutr., vol. 36, no. 2–4, pp. 109–132, 1997.

- O. Akinnawo and A. O. Ketiku, “Chemical composition and fatty acid profile of edible larva of Cirina forda (Westwood),” Afr. J. Biomed. Res., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 93–96, 2000, Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajbr/article/view/140723.

- M. F. A. Ivbijaro, “Poverty Alleviation from Biodiversity Management. Ibadan, Book Builders,” Ed. Afr., 2012.

- R. A. Akpossan, E. A. Dué, J. Kouadio, and L. P. Kouamé, “Nutritional value and physicochemical characterization of caterpillar fat (Imbrasia oyemensis) dried and sold at the Adjamé market (Abidjan, Ivory Coast),” J Plant Sci, vol. 3, pp. 243–250, 2009, Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.m.elewa.org/JAPS/2009/3.3/4.pdf.

- M. P. Balinga, “Caterpillars and edible larvae in the forest zone of Cameroon. FAO, Rome.” 2003.

- M. Leblanc and F. Malaisse, Lubumbashi, a tropical urban ecosystem. International Center for Semiology, National University of Zaire, 1978. Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=12630491.

- F. Malaisse and G. Parent, “Edible caterpillars of southern Shaba (Zaire),” 1980, Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=PASCALZOOLINEINRA8050235274.

- P. A. Hobane, “The urban marketing of the mopane worm: the case of Harare,” 1994, Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/4635/Hobane,%20PA%20%20CASS%20Occ%20Paper%20NRM%20series%20June%201994.pdf?sequence=1.

- I. Truncata Aurivillius, “Imbrasia truncata Aurivillius (Saturniidae): Importance in Central Africa, marketing and valorization in Brazzaville,” Geo-Eco-Trop, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 313–330, 2013, Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://geoecotrop.be/uploads/publications/pub_372_13.pdf.

- E. Mbétid-Bessane, “Marketing of edible caterpillars in the Central African Republic,” Tropicultura, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 3–5, 2005, Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Roger-Djoulde/publication/232060180_Selection_d’un_starter_destine_a_la_bioconversion_des_tubercules_de_manioc/links/0fcfd507448845b264000000/Selection-dun-starter-destine-a-la-bioconversion-des-tubercules-de- cassava.pdf# page=5.

- J. O. Fasoranti and D. O. Ajiboye, “Some edible insects of Kwara state, Nigeria,” Am. Entomol., vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 113–116, 1993, Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://academic.oup.com/ae/article-abstract/39/2/113/2474364.

- N. Siulapwa, A. Mwambungu, E. Lungu, and W. Sichilima, “Nutritional value of four common edible insects in Zambia,” Int J Sci Res, vol. 3, pp. 876–884, 2014, Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alick-Mwambungu-2/publication/335893221_Nutritional_Value_of_Four_Common_Edible_Insects_in_Zambia/links/5d828ebe92851ceb79140e91/Nutritional-Value-of-Four-Common-Edible-Insects-in-Zambia.pdf.

- O. Ndoye and A. Awono, “Congo livelihood improvement and food security project Supported by the US Agency for International...,” 2005, Accessed: Oct. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.academia.edu/download/50813389/CONGO_LIVELIHOOD_IMPROVEMENT_AND_FOOD_SE20161210-6766-fw6axw.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).