Submitted:

21 April 2024

Posted:

22 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Participants

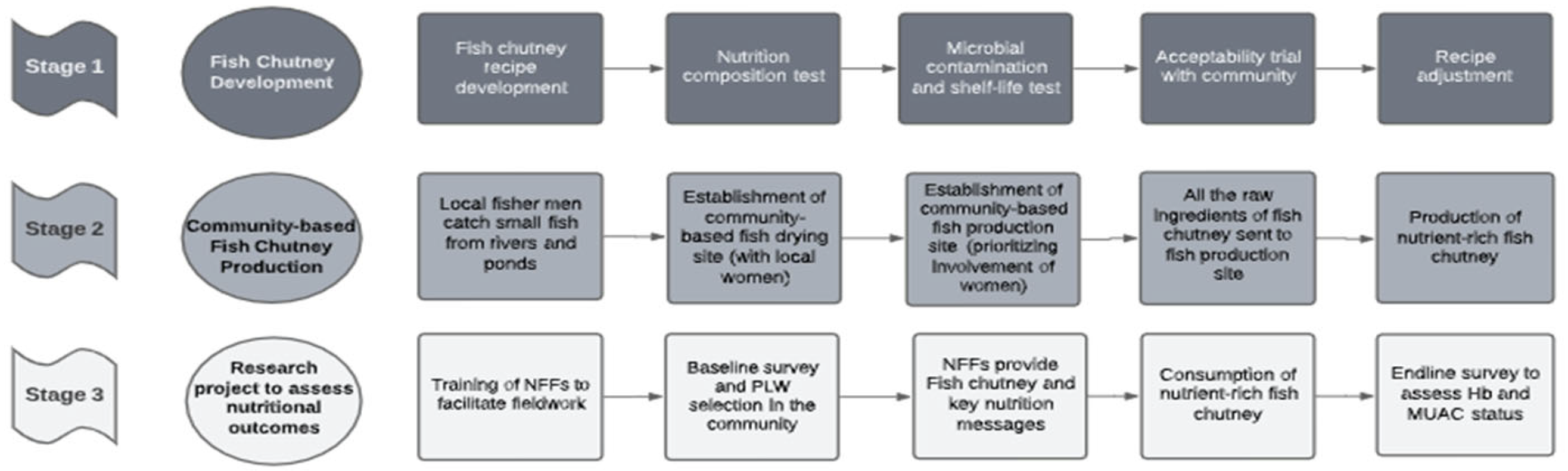

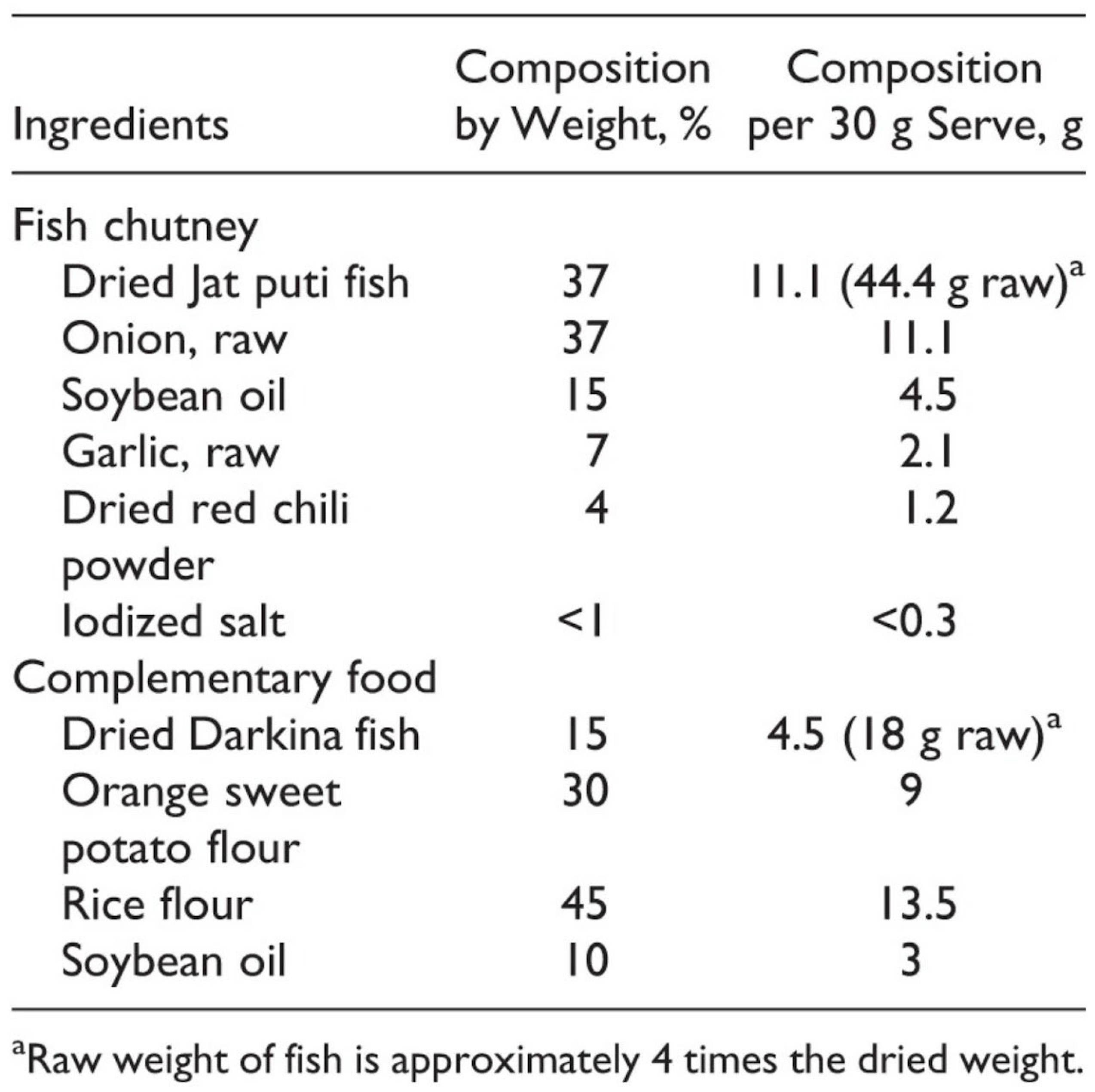

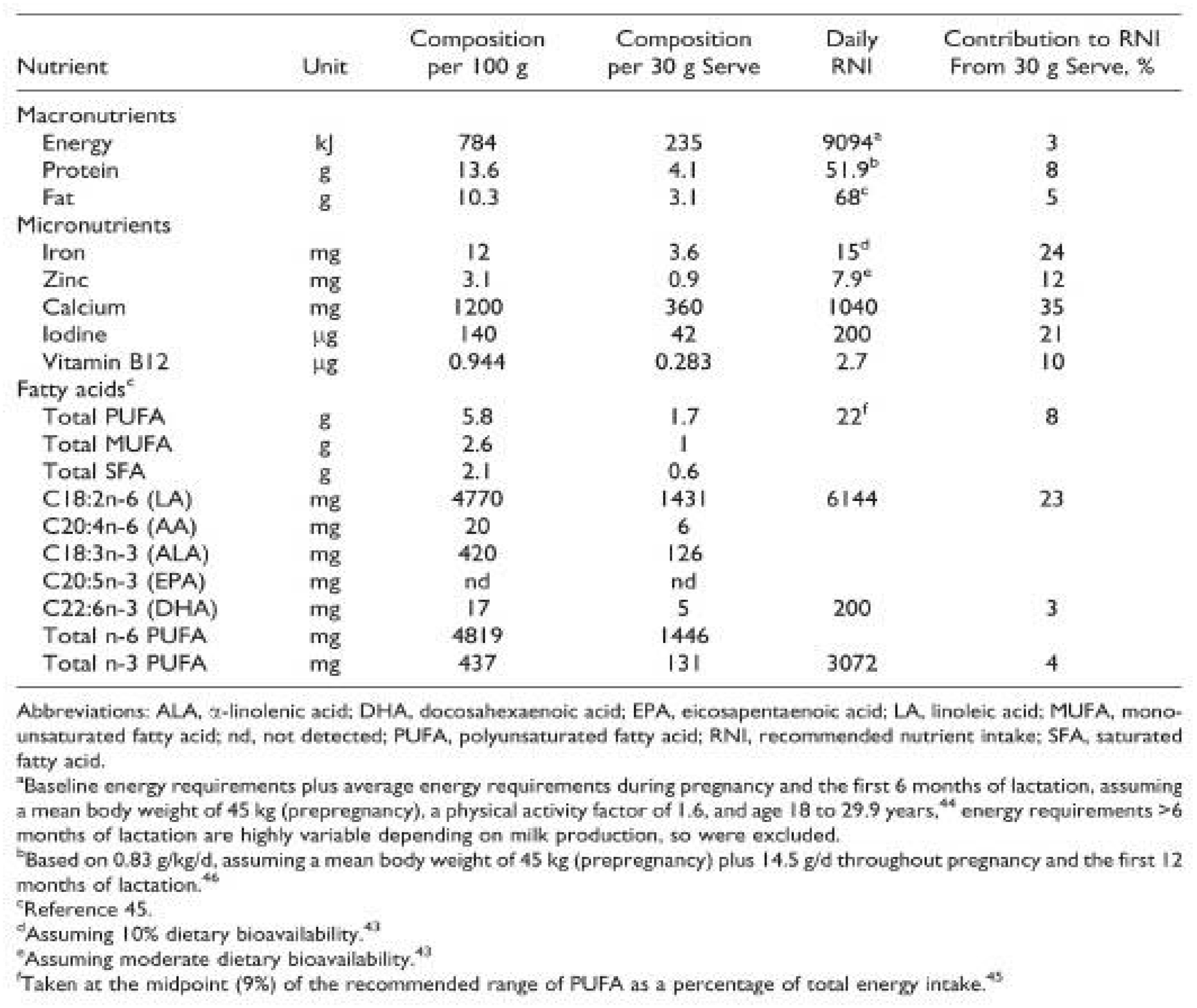

2.2. Stage 1: Fish Chutney Development

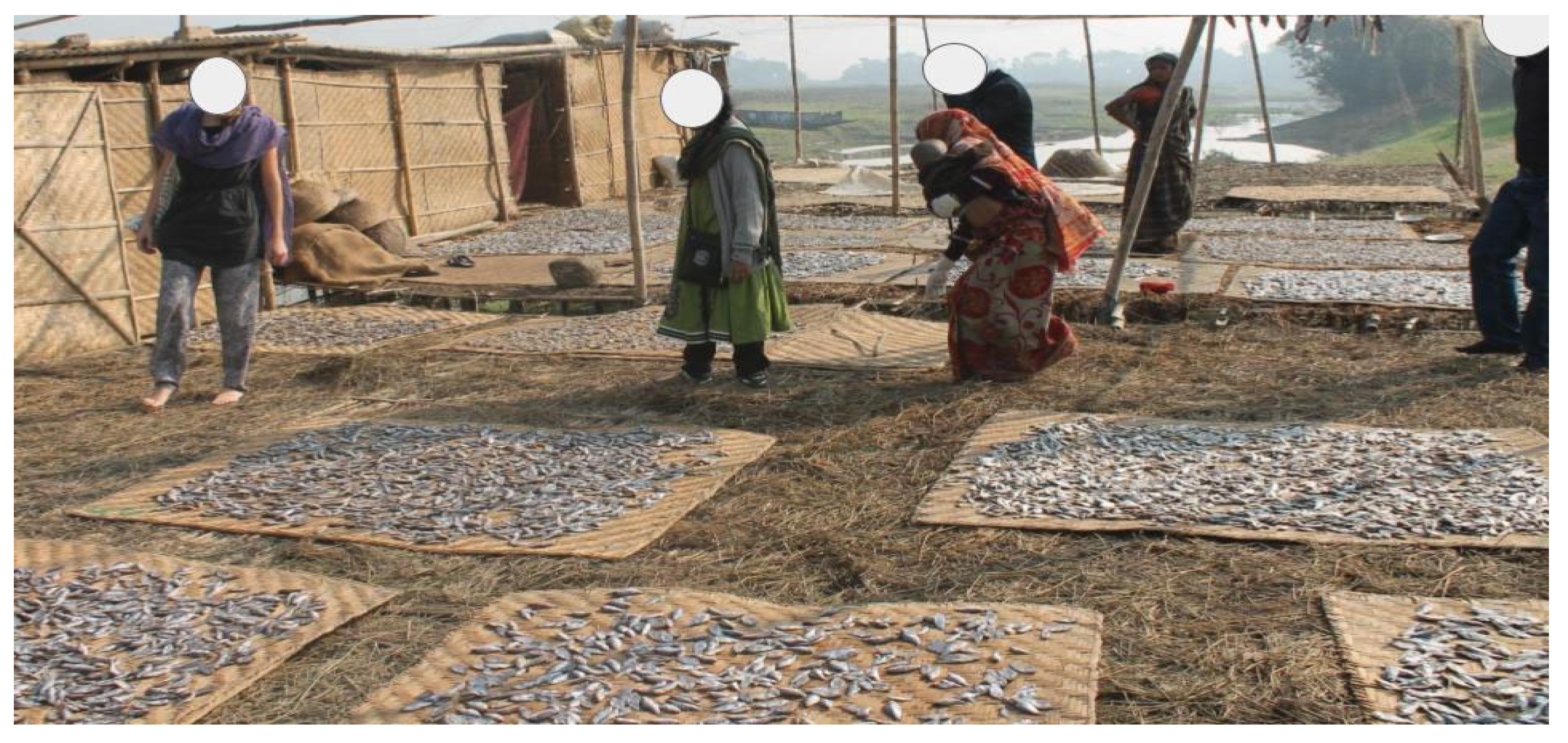

2.3. Stage 2: Community-Based Fish-Chutney Production

2.4. Stage 3: Nutritional Outcomes Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Blood Hemoglobin Concentration

3.2. Mid-Upper Arm Circumference

4. Discussion

- A rich source of protein and essential micronutrients, while ingredients are locally available and easy to prepare, providing opportunity for dietary diversity and a micronutrient rich diet during the food scarcity period in dry seasons;

- Fish chutney has a long shelf life of about 5-6 months, it uses of mustard oil, turmeric, garlic and vinegar, which increases its shelf life, as well as reducing the workload of the women by storing;

- Ready-to-use: fish chutney can be added to any traditional meal, such as rice, bread or chapatis;

- Suitable for local small-scale fisheries and community-based production to expand to commercial production and larger markets;

- Opportunity for women participation at each stage of production, especially in dried fish value chain approaches, which are already common in Bangladesh [45] and establish women’s empowerment in the community.

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malnutrition. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/malnutrition (accessed 2021-11-09).

- FAO, I. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020: Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets; The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI); FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO: Rome, Italy, 2020.

- Black, R. E.; Victora, C. G.; Walker, S. P.; Bhutta, Z. A.; Christian, P.; Onis, M. de; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; Uauy, R. Maternal and Child Undernutrition and Overweight in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. The Lancet 2013, 382 (9890), 427–451. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Mustafa, G.; Paul, T.; Wheeler, D. The Socioeconomics of Fish Consumption and Child Health: An Observational Cohort Study from Bangladesh. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105201. [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, Z. A.; Das, J. K.; Rizvi, A.; Gaffey, M. F.; Walker, N.; Horton, S.; Webb, P.; Lartey, A.; Black, R. E. Evidence-Based Interventions for Improvement of Maternal and Child Nutrition: What Can Be Done and at What Cost? The Lancet 2013, 382 (9890), 452–477. [CrossRef]

- Ruel, M. T.; Alderman, H. Nutrition-Sensitive Interventions and Programmes: How Can They Help to Accelerate Progress in Improving Maternal and Child Nutrition? The Lancet 2013, 382 (9891), 536–551. [CrossRef]

- Shepon, A.; Gephart, J. A.; Henriksson, P. J. G.; Jones, R.; Murshed-e-Jahan, K.; Eshel, G.; Golden, C. D. Reorientation of Aquaculture Production Systems Can Reduce Environmental Impacts and Improve Nutrition Security in Bangladesh. Nat. Food 2020, 1 (10), 640–647. [CrossRef]

- Committee on World Food Security. Coming to Terms with Terminology 2012; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2012; p 14. https://www.fao.org/3/md776e/md776e.pdf (accessed 2022-05-03).

- Akhtar, S. Malnutrition in South Asia—A Critical Reappraisal. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56 (14), 2320–2330. [CrossRef]

- Ghose, B.; Tang, S.; Yaya, S.; Feng, Z. Association between Food Insecurity and Anemia among Women of Reproductive Age. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1945. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, E. L.; Watson, L.; Berger, J.; Chea, M.; Chittchang, U.; Fahmida, U.; Khov, K.; Kounnavong, S.; Le, B. M.; Rojroongwasinkul, N.; Santika, O.; Sok, S.; Sok, D.; Do, T. T.; Thi, L. T.; Vonglokham, M.; Wieringa, F.; Wasantwisut, E.; Winichagoon, P. Realistic Food-Based Approaches Alone May Not Ensure Dietary Adequacy for Women and Young Children in South-East Asia. Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23 (1), 55–66. [CrossRef]

- NIPORT/Bangladesh, N. I. of P. R. and T.-; Associates/Bangladesh, M. and; Macro, O. R. C. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2004. 2005.

- NIPORT/Bangladesh, N. I. of P. R. and T.-; Associates/Bangladesh, M. and; International, I. C. F. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2013.

- Fishing for a future : women in community based fisheries management | WorldFish. https://www.worldfishcenter.org/publication/fishing-future-women-community-based-fisheries-management (accessed 2021-11-05).

- Hotz, C.; Loechl, C.; Brauw, A. de; Eozenou, P.; Gilligan, D.; Moursi, M.; Munhaua, B.; Jaarsveld, P. van; Carriquiry, A.; Meenakshi, J. V. A Large-Scale Intervention to Introduce Orange Sweet Potato in Rural Mozambique Increases Vitamin A Intakes among Children and Women. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108 (1), 163–176. [CrossRef]

- Hotz, C.; Loechl, C.; Lubowa, A.; Tumwine, J. K.; Ndeezi, G.; Nandutu Masawi, A.; Baingana, R.; Carriquiry, A.; de Brauw, A.; Meenakshi, J. V.; Gilligan, D. O. Introduction of β-Carotene–Rich Orange Sweet Potato in Rural Uganda Resulted in Increased Vitamin A Intakes among Children and Women and Improved Vitamin A Status among Children. J. Nutr. 2012, 142 (10), 1871–1880. [CrossRef]

- Khanam, M.; Ara, G.; Rahman, A. S.; Islam, Z.; Farhad, S.; Khan, S. S.; Sanin, K. I.; Rahman, M. M.; Majoor, H.; Ahmed, T. Factors Affecting Food Security in Women Enrolled in a Program for Vulnerable Group Development. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4 (4). [CrossRef]

- The Status of Food Security in the Feed the Future Zone and Other Regions of Bangladesh | FAO. https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/417259/ (accessed 2021-11-05).

- Byrd, K. A.; Thilsted, S. H.; Fiorella, K. J. Fish Nutrient Composition: A Review of Global Data from Poorly Assessed Inland and Marine Species. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24 (3), 476–486. [CrossRef]

- Byrd, K. A.; Pincus, L.; Pasqualino, M. M.; Muzofa, F.; Cole, S. M. Dried Small Fish Provide Nutrient Densities Important for the First 1000 Days. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2021, e13192. [CrossRef]

- Wheal, M. S.; DeCourcy-Ireland, E.; Bogard, J. R.; Thilsted, S. H.; Stangoulis, J. C. R. Measurement of Haem and Total Iron in Fish, Shrimp and Prawn Using ICP-MS: Implications for Dietary Iron Intake Calculations. Food Chem. 2016, 201, 222–229. [CrossRef]

- Sigh, S.; Roos, N.; Chamnan, C.; Laillou, A.; Prak, S.; Wieringa, F. T. Effectiveness of a Locally Produced, Fish-Based Food Product on Weight Gain among Cambodian Children in the Treatment of Acute Malnutrition: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10 (7), 909. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E.; Stacey, N.; Sunderland, T. C. H.; Adhuri, D. S. Dietary Diversity and Fish Consumption of Mothers and Their Children in Fisher Households in Komodo District, Eastern Indonesia. PLOS ONE 2020, 15 (4), e0230777. [CrossRef]

- Bogard, J. R.; Farook, S.; Marks, G. C.; Waid, J.; Belton, B.; Ali, M.; Toufique, K.; Mamun, A.; Thilsted, S. H. Higher Fish but Lower Micronutrient Intakes: Temporal Changes in Fish Consumption from Capture Fisheries and Aquaculture in Bangladesh. PLOS ONE 2017, 12 (4), e0175098. [CrossRef]

- Economic Empowerment of the Poorest in Bangladesh – Social Security Policy Support (SSPS) Programme. https://socialprotection.gov.bd/social-protection-pr/economic-empowerment-of-the-poorest-in-bangladesh/ (accessed 2023-07-06).

- Bogard, J. R.; Hother, A.-L.; Saha, M.; Bose, S.; Kabir, H.; Marks, G. C.; Thilsted, S. H. Inclusion of Small Indigenous Fish Improves Nutritional Quality During the First 1000 Days. Food Nutr. Bull. 2015, 36 (3), 276–289. [CrossRef]

- Nkrumah, B.; Nguah, S. B.; Sarpong, N.; Dekker, D.; Idriss, A.; May, J.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y. Hemoglobin Estimation by the HemoCue® Portable Hemoglobin Photometer in a Resource Poor Setting. BMC Clin. Pathol. 2011, 11 (1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Maternal Anthropometry and Pregnancy Outcomes. A WHO Collaborative Study. Bull. World Health Organ. 1995, 73 (Suppl), 1–98.

- Ververs, M.; Antierens, A.; Sackl, A.; Staderini, N.; Captier, V. Which Anthropometric Indicators Identify a Pregnant Woman as Acutely Malnourished and Predict Adverse Birth Outcomes in the Humanitarian Context? PLoS Curr. 2013, 5, ecurrents.dis.54a8b618c1bc031ea140e3f2934599c8. [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, S. H.; Chopra, H.; Sahariah, S. A.; Bhat, D.; Munshi, R. P.; Panchal, F.; Young, S.; Brown, N.; Tarwande, D.; Gandhi, M.; Margetts, B. M.; Potdar, R. D.; Fall, C. H. D. Effects of a Food-Based Intervention on Markers of Micronutrient Status among Indian Women of Low Socio-Economic Status. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113 (5), 813–821. [CrossRef]

- Persson, L. Å.; Arifeen, S.; Ekström, E.-C.; Rasmussen, K. M.; Frongillo, E. A.; Yunus, M.; MINIMat Study Team, for the. Effects of Prenatal Micronutrient and Early Food Supplementation on Maternal Hemoglobin, Birth Weight, and Infant Mortality Among Children in Bangladesh: The MINIMat Randomized Trial. JAMA 2012, 307 (19), 2050–2059. [CrossRef]

- The role of small indigenous fish species in food and nutrition security in Bangladesh | WorldFish. https://www.worldfishcenter.org/publication/role-small-indigenous-fish-species-food-and-nutrition-security-bangladesh (accessed 2021-11-05).

- Ziauddin Hyder, S. M.; Haseen, F.; Khan, M.; Schaetzel, T.; Jalal, C. S. B.; Rahman, M.; Lönnerdal, B.; Mannar, V.; Mehansho, H. A Multiple-Micronutrient-Fortified Beverage Affects Hemoglobin, Iron, and Vitamin A Status and Growth in Adolescent Girls in Rural Bangladesh. J. Nutr. 2007, 137 (9), 2147–2153. [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Hoque, M. Perception and Practices of Food Habit and Nutritional Status of Adolescent Girls in Bangladesh: A Comparative Study between Garment Workers and School Going Girls. Int. J. Health Econ. Dev. 2015, 1 (2), 28–41.

- Hossain, M.; Belton, B.; Thilsted, S. Dried Fish Value Chain in Bangladesh; 2015.

- Gomna, A.; Rana, K. Inter-Household and Intra-Household Patterns of Fish and Meat Consumption in Fishing Communities in Two States in Nigeria. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 97 (1), 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.-A.; Garaway, C. J. “Fish Rescue Us from Hunger”: The Contribution of Aquatic Resources to Household Food Security on the Rufiji River Floodplain, Tanzania, East Africa. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46 (6), 831–848. [CrossRef]

- Thorne-Lyman, A. L.; Valpiani, N.; Akter, R.; Baten, M. A.; Genschick, S.; Karim, M.; Thilsted, S. H. Fish and Meat Are Often Withheld From the Diets of Infants 6 to 12 Months in Fish-Farming Households in Rural Bangladesh. Food Nutr. Bull. 2017, 38 (3), 354–368. [CrossRef]

- Thilsted, S. H. The Potential of Nutrient-Rich Small Fish Species in Aquaculture to Improve Human Nutrition and Health; 2012.

- Harris-Fry, H.; Shrestha, N.; Costello, A.; Saville, N. M. Determinants of Intra-Household Food Allocation between Adults in South Asia – a Systematic Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16 (1), 107. [CrossRef]

- Sraboni, E.; Malapit, H. J.; Quisumbing, A. R.; Ahmed, A. U. Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture: What Role for Food Security in Bangladesh? World Dev. 2014, 61, 11–52. [CrossRef]

- Women’s empowerment in agriculture index | IFPRI : International Food Policy Research Institute. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/womens-empowerment-agriculture-index (accessed 2021-11-05).

- Rabbanee, F. K.; Yasmin, S.; Haque, A. Women Involvement in Dry Fish Value Chain Approaches towards Sustainable Livelihood. Aust. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2012, 01 (12), 52–58. [CrossRef]

- The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. www.fao.org. [CrossRef]

- Harnessing aquaculture for healthy diets – Global Panel. https://www.glopan.org/resources-documents/harnessing-aquaculture-for-healthy-diets/ (accessed 2021-11-05).

- Pauly, D. How the Global Fish Market Contributes to Human Micronutrient Deficiencies. Nature 2019, 574 (7776), 41–42. [CrossRef]

- Kawarazuka, N.; Béné, C. Linking Small-Scale Fisheries and Aquaculture to Household Nutritional Security: An Overview. Food Secur. 2010, 2 (4), 343–357. [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.-J.; Taylor, W. W.; Lynch, A. J.; Cowx, I. G.; Douglas Beard, T.; Bartley, D.; Wu, F. Inland Capture Fishery Contributions to Global Food Security and Threats to Their Future. Glob. Food Secur. 2014, 3 (3), 142–148. [CrossRef]

- Owino, V. O.; Skau, J.; Omollo, S.; Konyole, S.; Kinyuru, J.; Estambale, B.; Owuor, B.; Nanna, R.; Friis, H. WinFood Data from Kenya and Cambodia: Constraints on Field Procedures. Food Nutr. Bull. 2015, 36 (1_suppl1), S41–S46. [CrossRef]

- Shekar, M.; Kakietek, J.; Dayton Eberwein, J.; Walters, D. An Investment Framework for Nutrition: Reaching the Global Targets for Stunting, Anemia, Breastfeeding and Wasting. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/nutrition/publication/an-investment-framework-for-nutrition-reaching-the-global-targets-for-stunting-anemia-breastfeeding-wasting (accessed 2021-11-05).

| Variable | Baseline (n=179) | Post-Intervention (n=156) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | CI (95%) | SD | P-Value3 | Mean | CI (95%) | SD | P-Value3 | ||

| All study women; pregnant and lactating | Hb1 (g/L) | 109.5 | 83 – 128 | 15.9 | 0.034 | 124.3 | 122– 126 | 13.7 | 0.003 |

| MUAC2 (mm) | 226.2 | 169 – 268 | 19.5 | <0.001 | 237.2 | 219– 292 | 25.2 | <0.001 | |

| Pregnant women | Hb1 (g/L) | 107.0 | 96 – 136 | 12.0 | 0.344 | 124.75 | 123– 127 | 12.7 | 0.410 |

| MUAC2 (mm) | 226.9 | 217 – 254 | 11.04 | <0.001 | 238.5 | 223– 257 | 15.9 | 0.183 | |

| Lactating women | Hb1 (g/L) | 111.6 | 69 – 120 | 16.2 | 0.132 | 124.1 | 123– 125 | 11.7 | 0.403 |

| MUAC2 (mm) | 209.4 | 198 –215 | 15.1 | 0.004 | 236.7 | 218– 253 | 12.7 | 0.011 | |

| Variable | Mean Difference | % Mean Difference | Significant Level (T-Test)3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All study women, pregnant and lactating | Hb1 | 14.8 | 13.5% | < 0.001 |

| MUAC2 | 11.0 | 4.9% | 0.548 | |

| Pregnant Women | Hb1 | 17.8 | 16.6% | 0.026 |

| MUAC2 | 11.6 | 5.11% | 0.874 | |

| Lactating Women | Hb1 | 12.5 | 11.2% | 0.023 |

| MUAC2 | 27.3 | 13.1% | 0.173 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).