Submitted:

19 April 2024

Posted:

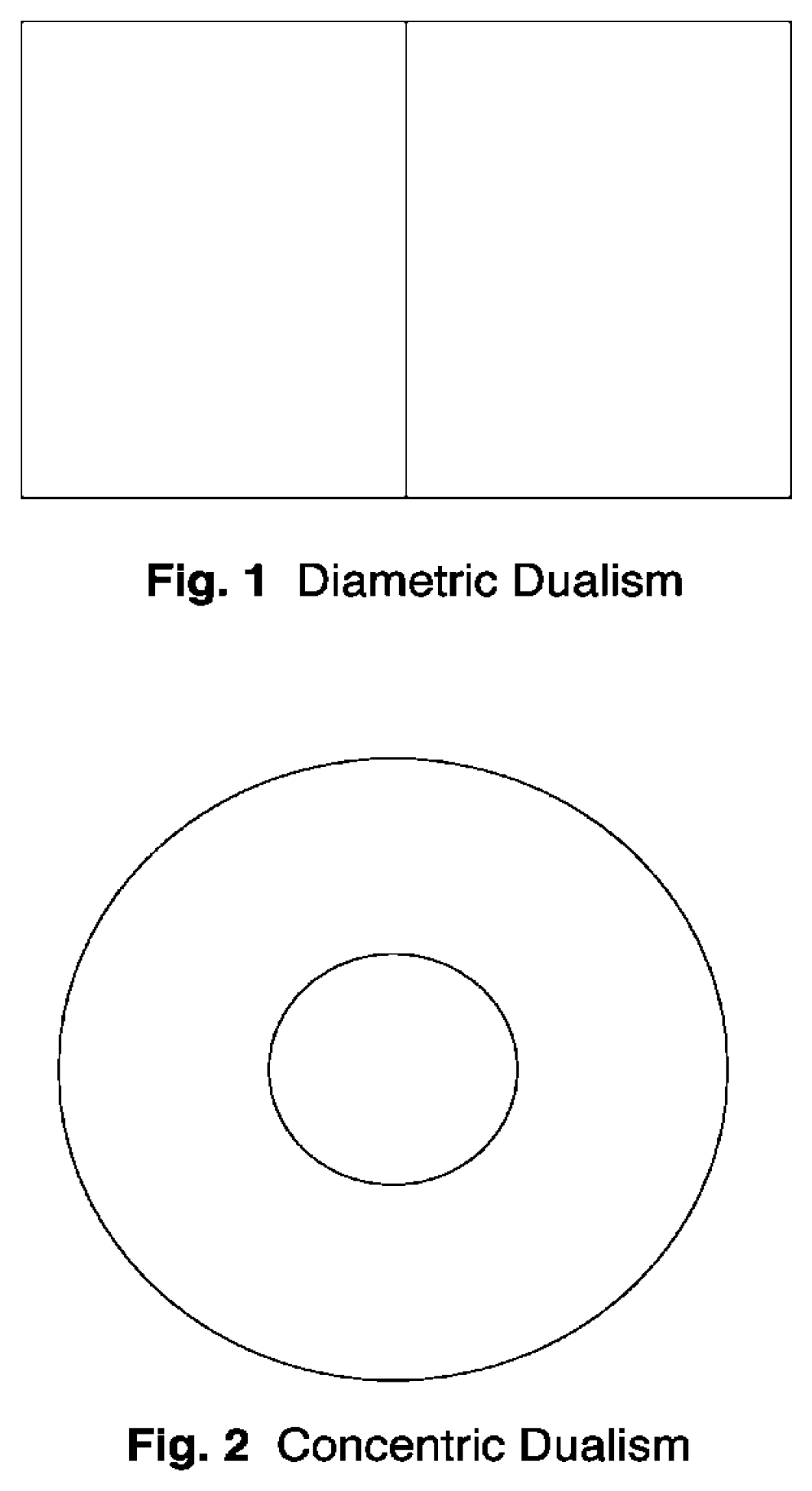

22 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Concentric Spatial Turn Building from the Initial Spatial Turn for Education, the Humanities and Social Sciences

2.1. Concentric Space as an Ancient and Cross-Cultural Structure

2.2. Emerging Research Towards the Concentric Spatial Turn

3. Key Contrasts between Diametric and Concentric Spatial Systems of Relation

3.1. Diametric Space as Assumed Separation between its Poles: Concentric Space as Assumed Connection between its Poles

3.2. Diametric Space as Mirror Image Inverted Symmetry

3.2. Diametric Space as Relative Closure and NonInteraction with Background: Concentric Space as Relative Openness and Interaction with Background

4. Developing a Concentric Space of Belonging with Nature, Being-Alongside the Natural World to Challenge Bacon’s Diametric Spatial Projection of Human’s Apart, Side-by-Side and Above the Natural World

5. Interpretative Methodological Issues for Uncovering Contrasts between Concentric and Diametric Space

5.1. Concentric and Diametric Spaces as Malleable Sustaining Conditions in Systems

5.2. Distinguishing Concentric and Diametric Spaces as Structures Versus Functions

5.3. Beyond Static Versus Dynamic Oppositions for Space to Treating Space as Both Positional and Directional Movement

5.4. A Concentric Spatial Turn as Broader Than Structuralism through Incorporating Phenomenology and Causal Reference in Systems

6. Discussion

Conclusion

Future Directions

References

- Schopenhauer, A. (1859/2010). The world as will and representation (Vol. I., Trans. J. Norman, A. Welchman, & C. Janaway). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p.379.

- Descartes, R. (1954). Descartes: Philosophical writings. Trans. E. Anscombe & P.T. Geach. London: Nelson, p.200.

- Downes, P. (2020a). Reconstructing agency in developmental and educational psychology: Inclusive Systems as Concentric Space. New York/London/New Delhi: Routledge.

- Massey, D. (2005). For space. London: Sage Publications.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Foucault, M. (1986). Of Other Spaces. Diacritics 16 (1) 22–27.

- Ferrare, J. J., & Apple, M. W. (2010). Spatializing critical education: Progress and cautions. Critical Studies in Education, 51, 209–221, p.216.

- Robertson, S. (2009). ‘Spatialising’ the Sociology of Education: Stand-points, Entry-points, Vantage-points. In S. Ball, M. Apple and L. Gandin (eds), Handbook of Sociology of Education, London and New York: Routledge.

- Vendra, M.C. & Furia, P. Introduction – Ricœur and the Problem of Space. Perspectives on a Ricœurian “Spatial Turn”. Ricœur Studies 2021, 12((2)), 1–7.

- Downes, P. At the Threshold of Ricoeur’s Concerns in La Métaphore Vive: A Spatial Discourse of Diametric and Concentric Structures of Relation Building on Lévi-Strauss. Ricoeur Studies/Etudes Ricoeuriennes 2016, 7 (2), 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E. W. (1996). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Downes, P. (2020b). Concentric Space as a Life Principle Beyond Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Ricoeur: Inclusion of the Other. New York/London/New Delhi: Routledge.

- Brand, A. L. The duality of space: The built world of Du Bois’ double-consciousness. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2018, 36(1), 3–22, p.7.

- Mannion, G. Going spatial, going relational: Why ‘listening to children’ and children’s participation needs reframing. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 2007, 28, 405–420, p.410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, F. (2007). Disability, education and space: Some critical reflections. In K. Gulson & C. Symes (Eds.), Spatial theories of education: Policy and geography matters (pp. 95–110). New York: Routledge, p.107.

- Cross, W. E. Jr. Ecological factors in human development. Child Development 2017, 88(3), 767–769, p.768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, M.A., Beech, J. Spatial theorizing in comparative and international education research. Comparative Education Review 2014, 58 (2), 191–214.

- Wong, B. Exploring the spatial belonging of students in higher education. Studies in Higher Education 2024, 49(3), 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, P., Li, G., Van Praag, L. & Lamb, S. (Eds.) (2024). The Routledge International Handbook of Equity and Inclusion in Education. London: Routledge.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Boston: Harvard University Press, p.22.

- Cefai, C. Downes, P. Cavioni.,V. (2021). A formative, inclusive, whole school approach to the assessment of social and emotional education in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union/EU bookshop.

- European Commission, European Education and Training Expert Panel (2019). Issue paper on Inclusion and citizenship. Brussels: Education and Training ET 2020.

- Downes, P., Anderson, J., Behtoui, A., Van Praag, L. (Eds.), (2024). Promoting Inclusive Systems for Migrants in Education. London: Routledge.

- Downes, P., Anderson, J., Nairz-Wirth E. Conclusion: Developing conceptual understandings of transitions and policy implications. European Journal of Education 2018, 53, 541–556. [CrossRef]

- Permana, A. S., Er, E., Aziz, N. A., & Ho, C. S. Three Sustainability Advantages of Urban Densification in a Concentric Urban Form: Evidence from Bandung City, Indonesia. International Journal of Built Environment and Sustainability 2015, 2(3). [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M.M.; Noaime, E. (2024). Spatial Dynamics and Social Order in Traditional Towns of Saudi Arabia’s Nadji Region: The Role of Neighborhood Clustering in Urban Morphology and Decision-Making Processes. Sustainability 16, 2830. p.6, p.12, p.14, p.19, p.11.

- Zhao, D., Shao, L., Li, J., & Shen, L. (2024). Spatial-performance evaluation of primary health care: Evidence from Xi’an, China. Sustainability, 16, 2838, p.1, p.12.

- Downes, P. (2012). The Primordial Dance: Diametric and Concentric Spaces in the Unconscious World. Oxford/Bern: Peter Lang.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural anthropology: Vol. 1. Trans. C. Jacobsen & B. Grundfest Schoepf. Allen Lane: Penguin, p.148., p.152, pp.139-140.

- Oslisy, R. (1996). The rock art of Gabon: Techniques, themes and estimation of its age by cultural association. In G. Pwiti, R.C. Soper (eds), Aspects of African archaeology: Papers from the 10th Congress of the PanAfrican Association for Prehistory and Related Studies, 361–70. Zimbabwe: University of Zimbabwe Publications.

- Nichols, R. (1990). The book of druidry. J. Matthews & P. Carr-Gorman (eds). London: Thorsons.

- Kriiska, A., Lougas, L. and Saluaar, U. (1997). Archaeological excavations of the Stone Age settlement site and ruin of the stone cist grave of the Early Metal Age in Kasekula. In U. Tamla (ed.), Archaeological field works in Estonia. Tallinn: Muinsuskaitseinspektsioon.

- Mandel, M. (1984). Minevikult tanapaevani. Estonia: Eesti raanat.

- Downes, P. (2011). Concentric and diametric structures in yin/yang and the mandala symbol: A new wave of Eastern frames for psychology.Psychology and Developing Societies, 23 (1), 121-153.

- Wilhelm, H. (1977). Heaven, earth and man in the Book of Changes. University of Washington Press.

- Leidy, D. P. (2008). The art of Buddhism: An introduction to its history and meaning. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

- Kerenyi, C. (1976). Dionysos: Archetypal image of indestructible life. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, p.95-96.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1973). Structural anthropology: Vol. 2. Trans. M. Layton, 1977. Allen Lane: Penguin Books, p.73, p.247, p.250, p.261.

- Bachelard, G. (1964). The poetics of space. Boston: Beacon Press, 1994, p.212, p. 116.

- Giorgi, S., Padiglione, V., & Pontevorco, C. Appropriations: Dynamics of domestic space negotiations in Italian middleclass working families. Culture and Psychology 2007, 13, 147–178.

- Bourdieu, P. (1970). The Berber house or the world reversed. Social Science Information, 9(2), 151-170.

- Streicker, J. (1997). Spatial reconfigurations, imagined geographies and social conflicts in Cartagena, Columbia. Cultural Anthropology, 12, 109–28.

- Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and time. Trans. J. MacQuarrie & E. Robinson, 1962. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, p.81-82.

- Heidegger, M. (1927a/1982). The basic problems of phenomenology. Trans. Albert Hofstadter Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Young, L., Vernon J. Linklater, V.J. and Pushor, D (2024). Walking Alongside: A Relational Conceptualization of Indigenous Parent Knowledge. In Downes, P., Li, G., Van Praag, L. & Lamb, S. (Eds.) (2024). The Routledge International Handbook of Equity and Inclusion in Education. London: Routledge.

- Cassirer, E. (1927/2020). The individual and the cosmos in Renaissance philosophy. Trans. M.Domandi. New York: Angelico Press, p.22, p.39, p.9, p.16, p.28.

- Said, E.W. (1978). Orientalism. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.45, p.68.

- Beauvoir, de S. (1949). The second sex. New York: Vintage, 1989.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1969). The elementary structures of kinship. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Bacon, F. (1620). Novum Organon, Aph. 59.

- Scalercio, M. (2018). Dominating nature and colonialism. Francis Bacon’s view of Europe and the New World. History of European Ideas, 44(8), 1076–1091.

- Descola, P. (2005/2013). Beyond nature and culture. University of Chicago Press, p.54, p.45.

- Montuschi, E. (2010). Order of man, order of nature: Francis Bacon’s idea of a ‘dominion’ over nature. Paper presented at the workshop ‘The Governance of Nature’, LSE 27/28 October 2010.

- Passmore, J. (1974). Man’s Responsibility for Nature, London: Duckworth,.

- D’Aquili, E. (1975). The influence of Jung on the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 11, 41–8.

- Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity. British Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 598–611, p.601.

- Gottlieb, G., & Halpern, C. T. (2002). A relational view of causality in normal and abnormal development. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 421–435.

- Mill, J.S. (1872). A system of logic. In R.F. McRae (ed.), Collected Works, Vol. VII, Books I, II, III. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1973, p.327.

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Evans, G. W. Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Social Development 2000, 9(1), 115–125, p. 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, S.C. (1987). Contributions of Roman Jakobsen. Annual Review of Anthropology, 16, 223–60.

- Ricoeur, P. (2006). Memory, History Forgetting. University of Chicago Press.

- Georgas, J., Mylonas, K., Bafiti, T., Poortinga, Y. H., Kag˘ itibas¸i, C., Orung, S., et al. (2001). Functional relationships in the nuclear and extended family: A 16-culture study. International Journal of Psychology, 36, 289–300.

- Marmor, A. (2001). Legal conventionalism. In J. Coleman (ed.), Hart’s postscript: Essays on the Postscript to the Concept of Law,193–218. Oxford: Oxford University Press p. 210.

- Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York: Basic Books, pp. 3–30.

- Kearney, R. (2003). Strangers, Gods and Monsters: Interpreting otherness. London & New York: Routledge.

- Jameson, F. (2009). Valences of the dialectic. London: Verso.

- Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling society. New York: Harper and Row.

- Brady, S (2022). A Reconceptualisation of Froebel’s Approach to Nature to Examine the Perceived Impact of Children’s Participation in a School Garden on their Social and Emotional Development in a DEIS Band 1 Primary School. M.Ed Thesis, DCU Institute of Education, Educational Disadvantage Centre.

- Gilligan, C. & Downes, P. (2022). Reconfiguring Relational Space: A Qualitative Study of the Benefits of Caring for Hens for the Socio-Emotional Development of 5 – 9-year-old Children in an Urban Junior School context of High Socio-Economic Exclusion. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning,22 (2) 148-164.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).