1. Introduction

Pneumonia, an infection of the pulmonary parenchyma, is a significant health concern globally and associated with considerable mortality [

1]. Many studies have reported prognostic factors for pneumonia, and patients with severe pneumonia have higher mortality and a poorer prognosis [

2,

3,

4]. Even if they survive, patients with severe pneumonia are prone to becoming chronically and critically ill, and this long-term detrimental outcome can lead to economic collapse of the patient’s family due to the financial burden and ultimately national loss [

5,

6].

To alleviate the financial burden on hospitalized patients, various healthcare insurance systems exist in different countries [

7]. In Korea, there is a system known as the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) program. The entire Korean population can receive financial support through the NHIS [

8], which has been updated annually since its inception in 1977. One of the most important updates of the NHIS was implementation of the health insurance benefit extension policy, which targets patients with rare incurable disease such as hemato-oncological, cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and rare diseases [

9]. These benefit items under the health insurance benefit extension policy has provided great financial assistance and its coverage has progressively expanded. A previous study investigated the relationship between the benefit items and the clinical outcomes of patients requiring mechanical ventilation (MV) in intensive care units (ICUs), and reported the usefulness of this policy in ventilated patients [

10]. However, this study was performed at a single center and the etiology of the patient population was highly heterogeneous.

In the critical care field, the utilization of big data has emerged as a powerful tool for comprehensive analyses. The NHIS database provides extensive patient data, covering patients’ demographics, treatment modalities, and outcomes [

11]. Based on analysis of big data from the NHIS database, we hypothesized that the health insurance benefit extension policy may be beneficial for critically ill patients.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the relationship between 1-year mortality and the benefit items in patients with severe pneumonia requiring MV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Patient Population

This study was conducted by extracting data from the NHIS database. This database represents a public health insurance system in South Korea, containing information about disease diagnoses, drug prescriptions and procedural data for all citizens. It encompasses a stratified random sample of 1 million individuals enrolled in the NHIS since 2002. Diseases are registered based on the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10 codes).

Data of patients who were admitted to ICUs in South Korea between January 2016 and December 2018 were retrospectively evaluated using the NHIS database. Adult (age ≥ 18 years) patients who were primarily diagnosed with pneumonia and required MV for more than 24 hours were included. Data on the survival status of all patients was collected until December 31, 2019. Beneficiaries of Medical Aid (MA) were not included because MA caters for low-income families, offering healthcare benefits and establishing an upper limit for out-of-pocket medical expenditure in accordance with the National Basic Living Security Act. Consequently, the benefit items have minimal impact on the clinical outcomes of MA beneficiaries.

The research protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Hospital (IRB No. 2208-020-118). The NHIS permitted data sharing after approval of the study protocol (NHIS-2023-2-063).

2.2. Data Collection and Definitions

From the NHIS database, demographic and clinical information such as age, sex, duration of stay in both the ICU and hospital, and the length of mechanical ventilation (MV) usage, was collected retrospectively. ICD-10 codes of pneumonia range from viral pneumonia (J10) to unspecified pneumonia (J18). We did not distinguish between community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia according to practice guidelines [

12,

13]. Diseases covered by the health insurance benefit extension policy have codes beginning with ‘V’, which are separate from the ICD-10 codes. We divided patients covered by the benefit items into four groups, namely, the hemato-oncological disease, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, and rare disease groups. Hemato-oncologic diseases included solid and liquid malignant tumors. Cerebrovascular diseases included cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, carotid artery dissection, and any brain damage that required brain surgery. Cardiovascular diseases included ischemic heart disease, pulmonary thromboembolism, aortic dissection, and other heart diseases. Rare diseases included various congenital, autoimmune, and neuromuscular diseases and other rare diseases. The detailed codes for each group are listed in

Supplementary Table S1.

The primary outcome was 1-year mortality. The secondary outcomes were vasopressor use, renal replacement therapy use, LOS in the ICU and hospital, and medical expenditures. Expenditures, both total and out-of-pocket, are reported in U.S. dollars (USD), converted from Korean won at a rate of 1 USD to 1,303.0 Korean won, based on the exchange rate as of December 18, 2023. Furthermore, the main applicable benefit items under the health insurance benefit extension policy to reduce each patient’s out-of-pocket medical expenditure during their hospital stay were assessed.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data, or the median with interquartile range otherwise. For continuous variables, the Student's t-test was applied to those with a normal distribution, while the Wilcoxon rank sum test was utilized for variables without normal distribution. Categorical variables are presented as counts (percentages) and were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test (for small numbers), as applicable. ANOVA test was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference of a continuous variable between three or more study groups. Post hoc analysis was conducted for multiple comparisons, and the significance level was adjusted using the Bonferroni method. The Kruskal-Wallis test was employed to evaluate the statistical significance of differences in an ordinal variable between three or more study groups. Univariate proportional hazard models were constructed to evaluate the association between the benefit items and in-hospital mortality. Hazard ratios are presented along with 95% confidence intervals. In-hospital mortality rates, estimated via Kaplan-Meier methods, were categorized based on the status of benefit items, and the differences between these curves were analyzed using the log-rank test. Each test was conducted using a two-tailed approach, with P-values <0.05 regarded as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the SAS Enterprise Guide version 8.3 (2017-2020, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Total Patients

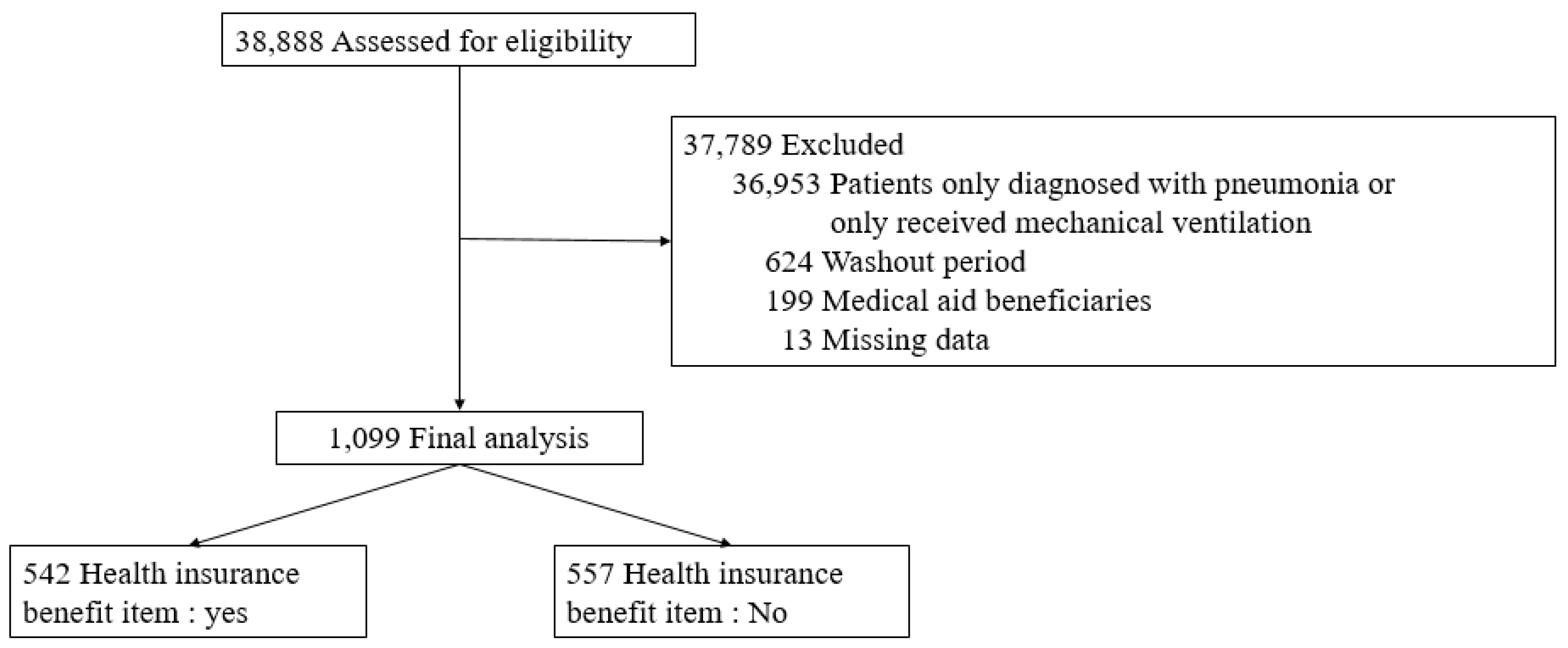

During the enrollment period, 38,888 patients were screened, of whom 37,789 were excluded (

Figure 1). Thus, 1,099 patients were included in the final analysis. Their baseline characteristics are shown in

Table 1. The 6-month and 1-year cumulative mortality rates were 56.5% and 61.9%, respectively. The median LOS was 35.7 days (SD: 36.9 days) in the ICU and 139.6 days (SD: 215.8 days) in the hospital. During the hospitalization, the median total medical expenditures were 22,261 USD (range: 11,707–43,233 USD), while out-of-pocket expenses were a median of 2,733 USD (range: 1,279–6,122 USD), respectively.

3.2. Comparisons of Patients with and without Benefit Items under the Health Insurance Benefit Extension Policy

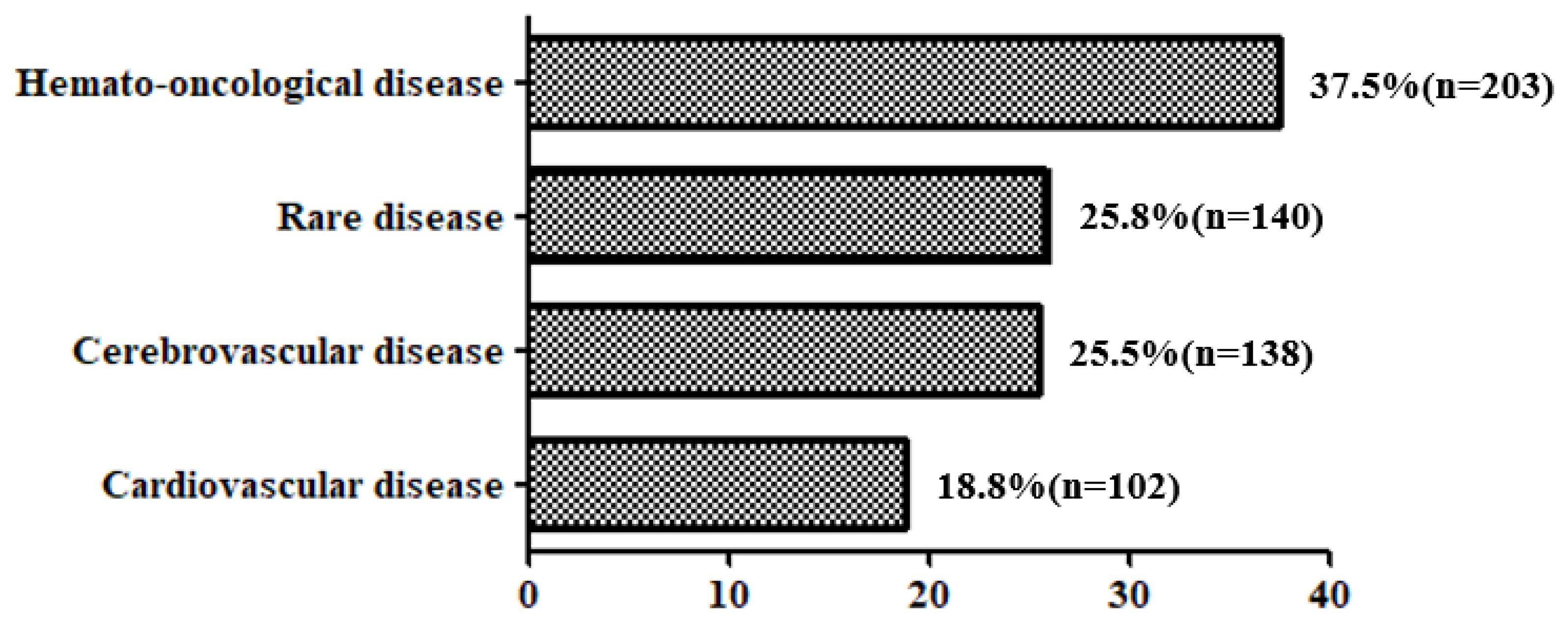

Of total patients, 542 patients (49.3%) had each benefit items under this policy (

Figure 2). The clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients in the four benefit item categories are shown in

Supplementary Table S2. We further divided these four categories into two groups. Patients with hemato-oncological diseases as benefit items were classified into group A, while other patients were classified into group B.

Table 2 compares the clinical characteristics and outcomes between patients without benefit items and those within groups A and B. Patients without benefit items were older than those with benefit items. Patients in group B had significantly longer hospital, ICU, and MV LOS. During their hospital stay, they had significantly higher total medical expenditure and exhibited an increased need for renal replacement therapy and tracheostomy. Furthermore, they had significantly lower 6-month and 1-year cumulative mortality rates. By contrast, patients in group A showed a significantly lower percentage of out-of-pocket medical expenditure in relation to total medical expenditure compared to those in the other two groups. They also had a higher rate of requirement for vasopressor infusion during their hospital stay and a higher 1-year cumulative mortality rate.

3.3. Characteristics of Total Patients

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to analyze the relationship between benefit items and 1-year mortality among all enrolled patients (

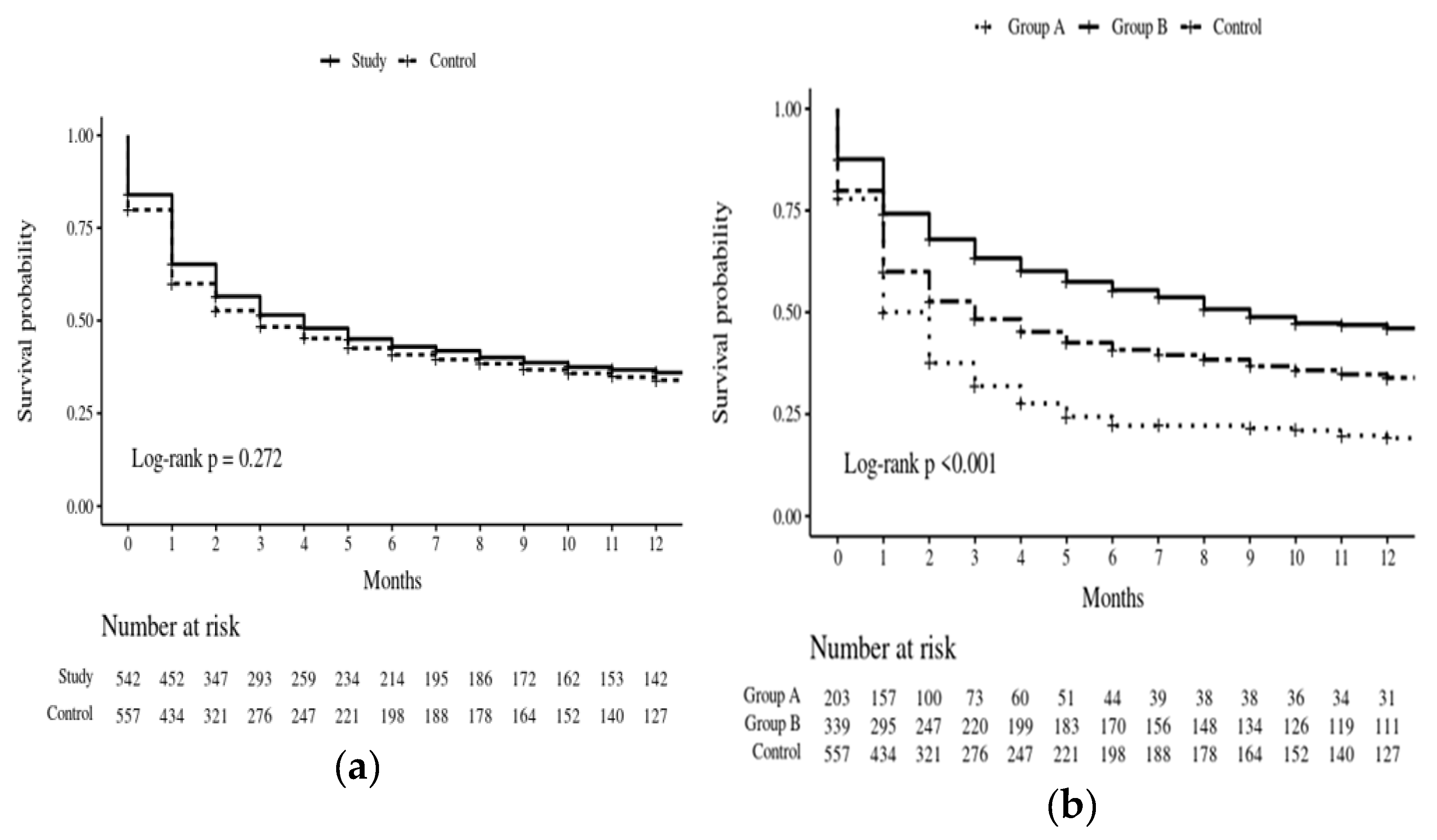

Table 3). Group B benefit items were associated with a better survival rate in both univariate and multivariate analyses. The Kaplan-Meier survival estimate correlated with the categories of benefit items, as shown in

Figure 3. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of survival did not significantly differ between patients covered by the health insurance benefit extension policy and control patients (

Figure 3A). However, the survival curves of patients in group A, group B, and the control group significantly differed according to the log-rank test (P<0.001), and patients in group B had the highest survival probability (

Figure 3B).

4. Discussion

Our study investigated the impact of the NHIS health insurance benefit extension policy on long-term outcomes of patients diagnosed with severe pneumonia requiring MV. This analysis utilized the largest national dataset representing the entire Korean population. Our findings revealed a positive association between the benefit items covered under this policy and 1-year mortality among critically ill patients receiving MV for severe pneumonia. To our knowledge, this study is the first to illustrate the potential influence of a government-driven medical expenditure reduction policy on the outcomes of critically ill patients.

There was no significant difference in the 1-year mortality rate between patients with benefit items and those without. However, upon further analysis by categorizing the entire range of benefit items into four groups, we observed variations in the 1-year mortality rate according to the specific benefit items. Notably, patients with group B benefit items had a lower 1-year mortality rate than those with group A benefit items and those without any benefit items. Patients of group B received more medical resources during their ICU stay, and their out-of-pocket medical expenditure was significantly lower than those of patients with group A benefit items and patients without any benefit items. These results suggest that critical care physicians have the opportunity to allocate more medical resources for optimal treatment in patients with these specific benefit items [

14]. Furthermore, it is imperative that physicians consider the benefit items of critically ill patients when planning future treatments in collaboration with their families and surrogates [

10].

Patients of group A had lower out-of-pocket medical expenditure as a proportion of total medical expenditure compared to those of group B and those without any benefit items. However, they had a significantly higher 1-year mortality rate. The clinical outcomes of patients with group A benefit items varied according to factors such as the type and stage at initial diagnosis and the treatment process. Additionally, outcomes depended on whether patients achieved remission following treatment or progressed to an advanced or terminal stage despite treatment. The retrospective design of this study limited our ability to assess the impact of these benefit items on clinical outcomes according to various clinical courses. Further research involving a larger number of patients is necessary to evaluate the effects of benefit items on the prognosis of critically ill patients with hemato-oncologic malignancies.

Approximately 50% of total enrolled patients were considered eligible for at least one benefit item during their hospitalization. Our findings suggest that national health insurance policies lower the threshold for medical utilization, potentially leading to increased use of medical resources [

14]. However, literature concerning the association between government-driven health insurance policies and clinical outcomes, particularly in the critical care field, is limited. The introduction of insurance benefits established by the government for patients with life-threatening diagnoses (such as septic shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome) may improve outcomes.

This study represents several limitations. First, our study had a retrospective observational design, making it susceptible to unmeasured confounders. Therefore, further research performing statistical analysis of various variables is necessary. Second, we were unable to assess severity-of-illness and organ failure scores, such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores [

15,

16], as well as pneumonia severity index (PSI) and CURB 65 scores [

17,

18], at ICU admission because various parameters necessary to calculate these scores were not recorded in the NHIS database. Third, although we hypothesized that long-term outcomes differed according to whether patients had community- or hospital-acquired pneumonia, we could not accurately distinguish between these diagnoses due to the retrospective design.

5. Conclusions

In this nationwide cohort analysis of patients with pneumonia requiring MV, patients eligible for benefit items in three categories (cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and rare diseases) under the national health insurance benefit extension policy in Korea had a lower 1-year mortality rate. Large-scale studies are warranted to assess the impact of these government-driven medical expenditure reduction items on clinical outcomes in the critical care field.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: ICD-10-based classification of V-coded diseases with health insurance benefit extension policy; Table S2: Demographic and Clinical characteristics of patients with each health insurance benefit extension policy item.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y. and K.L.; methodology, K.L.; software, J.S. and J.K.; validation, M.K.L., H.P. and Y.K.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, H.J.; resources, W.Y.; data curation, K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Y.; writing—review and editing, K.L.; visualization, J.S. and J.K.; supervision, M.K.L.; project administration, H.P.; funding acquisition, W.Y.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Hospital (IRB No. 2208-020-118).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived from all subjects or their families involved in the study, because our study was observational, retrospective design.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy regulations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Biomedical Research Institute Grant (20220195), Pusan National University Hospital

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Johnstone, J.; Eurich, D.T.; Majumdar, S.R.; Jin, Y.; Marrie, T.J. Long-term morbidity and mortality after hospitalization with community-acquired pneumonia: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008, 87, 329-334. [CrossRef]

- Metersky, M.L.; Waterer, G.; Nsa, W.; Bratzler, D.W. Predictors of in-hospital vs postdischarge mortality in pneumonia. Chest. 2012, 142, 476-481. [CrossRef]

- File T.M.; Ramirez, J.A. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2023, 389, 632-641.

- Cillóniz, C.; Torres, A.; Niederman, M.S. Management of pneumonia in critically ill patients. BMJ. 2021, 375, e065871. [CrossRef]

- Furman, C.D.; Leinenbach, A.; Usher, R.; Elikkottil, J.; Arnold, F.W. Pneumonia in older adults. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2021, 34, 135-141. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T.; Navathe, A.S.; Werner, R.M. Pneumonia is not just pneumonia: Differences in utilization and costs with common comorbidities. J Hosp Med. 2023, 18, 1004-1007. [CrossRef]

- Campling, J.; Wright, H.F.; Hall, G.C.; Mugwagwa, T.; Vyse, A.; Mendes, D.; Slack, M.P.E.; Ellsbury, G.F. Hospitalization costs of adult community-acquired pneumonia in England. J Med Econ. 2022, 25, 912-918. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/eng/pl/pl0101.jsp PAR_MENU_ID=1003&MENU_ID=100324. (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- An, J.; Kim, S. Medical cost trends under national health insurance benefit extension in Republic of Korea. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2020, 35, 1351-1370. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Jeong, E.; Lee, K. Association between the National Health Insurance coverage benefit extension policy and clinical outcomes of ventilated patients: a retrospective study. Acute Crit Care. 2022, 37, 53-60. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.S.; Park, S.H.; Shin, S.A.; Kim, K. Cohort Profile: The National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC), South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017, 46, e15. [CrossRef]

- Metlay, J.P.; Waterer, G.W.; Long, A.C.; Anzueto, A.; Brozek, J.; Crothers, K.; Cooley, L.A.; Dean, N.C.; Fine, M.J.; Flanders, S.A.; Griffin, M.R.; Metersky, M.L.; Musher, D.M.; Restrepo, M.I.; Whitney, C.G. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019, 200, e45-e67. [CrossRef]

- Kalil, A.C.; Metersky, M.L.; Klompas, M.; Muscedere, J.; Sweeney, D.A.; Palmer, L.B.; Napolitano, L.M.; O'Grady, N.P.; Bartlett, J.G.; Carratalà, J.; El Solh, A.A.; Ewig, S.; Fey, P.D.; File, T.M.; Restrepo, M.I.; Roberts, J.A.; Waterer, G.W.; Cruse, P.; Knight, S.L.; Brozek, J.L. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016, 63, e61-e111. [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Kim, S. Medical cost trends under national health insurance benefit extension in Republic of Korea. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2020, 35, 1351-1370. [CrossRef]

- Knaus, W.A.; Draper, E.A.; Wagner, D.P.; Zimmerman, J.E. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985, 13, 818-29.

- Vincent, J.L.; Moreno, R.; Takala, J.; Willatts, S.; Mendonça, A.; Bruining, H.; Reinhart, C.K.; Suter, P.M.; Thijs, L.G. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996, 22, 707-10. [CrossRef]

- Fine, M.J.; Auble, T.E.; Yealy, D.M.; Hanusa, B.H.; Weissfeld, L.A.; Singer, D.E.; Coley, C.M.; Marrie, T.J.; Kapoor, W.N. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997, 336, 243-50. [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.S.; Macfarlane, J.T.; Boswell, T.C.; Harrison, T.G.; Rose, D.; Leinonen, M.; Saikku, P. Study of community acquired pneumonia aetiology (SCAPA) in adults admitted to hospital: implications for management guidelines. Thorax. 2001, 56, 296-301.1. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).