Introduction & Background

The landscape of medical education is in a state of continuous evolution, adapting to the ever-changing demands of healthcare and the advances in educational theory. A critical aspect of this transformation is the assessment strategies employed to evaluate medical students. Traditional examinations, predominantly closed-book in nature, have long been the cornerstone of academic evaluation [

1]. However, in recent decades, there has been a paradigm shift towards more innovative assessment methods, one of which is the open-book examination (OBE) [

2].

An OBE is a type of assessment method in which the students are allowed to consult approved resources permitted material while attempting the examination [

3].The approved resources could include class notes, textbooks, primary or secondary readings, and/or access the internet when answering questions. The inception of OBEs in medical education marks a significant departure from conventional memorization-based assessments. Unlike closed-book exams, which often prioritize rote learning and recall, open-book exams encourage students to understand, analyze, and apply knowledge, mirroring the realities of clinical practice where resources and references are readily available [

4]. This shift acknowledges the immense body of medical knowledge, continuously expanding and evolving, making it impractical and unnecessary for students to memorize vast quantities of information. [

1]

Critically, OBEs aim to assess a student's ability to efficiently locate and utilize information, skills that are essential for practising physicians who must navigate a plethora of clinical data and evidence-based guidelines in their daily practice [

2,

5,

6]. This approach aligns assessment methods with the practical demands of modern healthcare, emphasizing the application of knowledge rather than its mere recall. 6] It also reflects a broader educational philosophy that values lifelong learning and adaptability, skills that are indispensable in a profession characterized by rapid advancements and constant change [

7].

However, the implementation of OBEs in medical education is not without challenges. Questions arise regarding their ability to rigorously assess student competence, the potential for academic dishonesty, and the need for carefully crafted questions that probe deeper levels of understanding. Additionally, there is a debate on how well OBEs prepare students for high-stakes, closed-book examinations like licensing and board certification tests, which remain a reality in the medical profession [

8].

The efficacy of OBEs also hinges on the pedagogical framework within which they are employed. They demand a curriculum that fosters independent learning, critical thinking, and efficient information management. Instructors play a pivotal role in crafting questions that test knowledge application and problem-solving skills, mitigate the risk of superficial learning, and encourage a thorough understanding of core concepts [

9].

In exploring the role of OBEs, it is imperative to consider their impact on students' learning experiences, study behaviours, and academic performance. Research suggests that OBEs can reduce examination-related anxiety, promote a deeper engagement with the material, and encourage a more strategic approach to learning [

10]. However, there is also a need to understand the perspectives of both students and educators on the effectiveness of this assessment method, its impact on learning outcomes, and the challenges encountered in its implementation.

As the medical field continues to advance, so must the methods we use to educate and assess future physicians. Open-book examinations represent a progressive step in aligning medical education with the realities of clinical practice and the principles of adult learning theory. By embracing this innovative assessment approach, medical education can foster a generation of doctors who are not only knowledgeable but also adept at navigating the vast landscape of medical information, which is critical in making informed, evidence-based decisions in patient care [

11].

The exploration of open-book examinations in medical education offers valuable insights into how assessment strategies can evolve to better prepare students for the demands of modern medical practice. This exploration is not just about changing how we test but also about redefining what and how we teach, ensuring that medical education remains relevant, effective, and responsive to the needs of students and the healthcare systems they will serve.

Assessment in medical schools during times of crisis, such as pandemics like COVID-19, war, and natural disasters, poses unique challenges that can significantly impact the quality and effectiveness of medical education. Moat recently COVID-19 pandemic has had significant impacts both the delivery of education and the implementation of fair, effective evaluation methods, highlighting the need to evaluate our students with the utmost quality and reliability [

12,

13]. Social distancing requirements and the challenges associated with ensuring rigorous examination conditions have, in numerous instances, made the administration of conventional traditional closed-book exams impossible. The experience gained during this period should continue and be scientifically based to be used more effectively, with greater confidence and knowledge.

Thus, this study aimed to systematically investigate the integration of open-book examinations as an educational assessment method in the medical curriculum, with a focus on understanding the pedagogical approaches, challenges, and learning outcomes associated with their implementation.

Methods

Ethics statement

This was a literature-based study; therefore, neither approval from the institutional review board nor informed consent was required.

Design

This was an integrative review, described in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

The following research question guided this review: How do open-book examinations impact the learning process and academic performance of medical students compared to traditional closed-book examinations?

To structure this review, and answer this research question, we used Whittemore and Knafl's framework for integrated reviews [

14] Integrative review is a form of research that reviews, critiques and synthesises representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. It presents a unique approach by combining and synthesizing data from diverse research designs including qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of interest [

15,

16].

Eligibility criteria

The PICOS (population, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design) framework was used to develop search term for the systematic review and was the foundation for study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Search strategies.

Information sources

A comprehensive systematic search of the literature was conducted using four electronic databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and ERIC.

The databases were checked for English-language studies published from 2013 to 2023.

Search strategy.

Two reviewers (Y.A., S.K.) independently conducted a systematic search for studies evaluating open-book examination in medical education.

We utilized a group of descriptors, combined using the Boolean operator "AND" and "OR" The following key search terms were used for databases “medicine,” “assessment,” “open book examination,” “open book exam,” “open book test,” and “open book assessment.” Using 6 descriptors, we performed a total of 30 search combinations.

Selection process.

The process began by defining the theme, in this case, open-book examinations in medical education. This allowed us to identify specific descriptors or keywords relevant to the subject.

Data management of this systematic review study was done using Zotero version 6.0.30 (Corporation for Digital Scholarship, Vienna, VA, USA).

Titles and abstracts were initially screened by 2 researchers (YA, SK) separately to identify potentially included articles. Subsequently, the full articles were thoroughly reviewed by both reviewers against the eligibility criteria. Consensus was reached by the research team on the final list of articles to be included. The other 2 researchers (MW, MA) resolved any contradictions between the 2 researchers in selecting studies. Given the diverse range of research methodologies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was adapted. This adaptation closely followed the well-documented modifications introduced by Halcomb et al [

17,

18]. Finally, to prevent data loss, the list of study references was evaluated manually.

Results

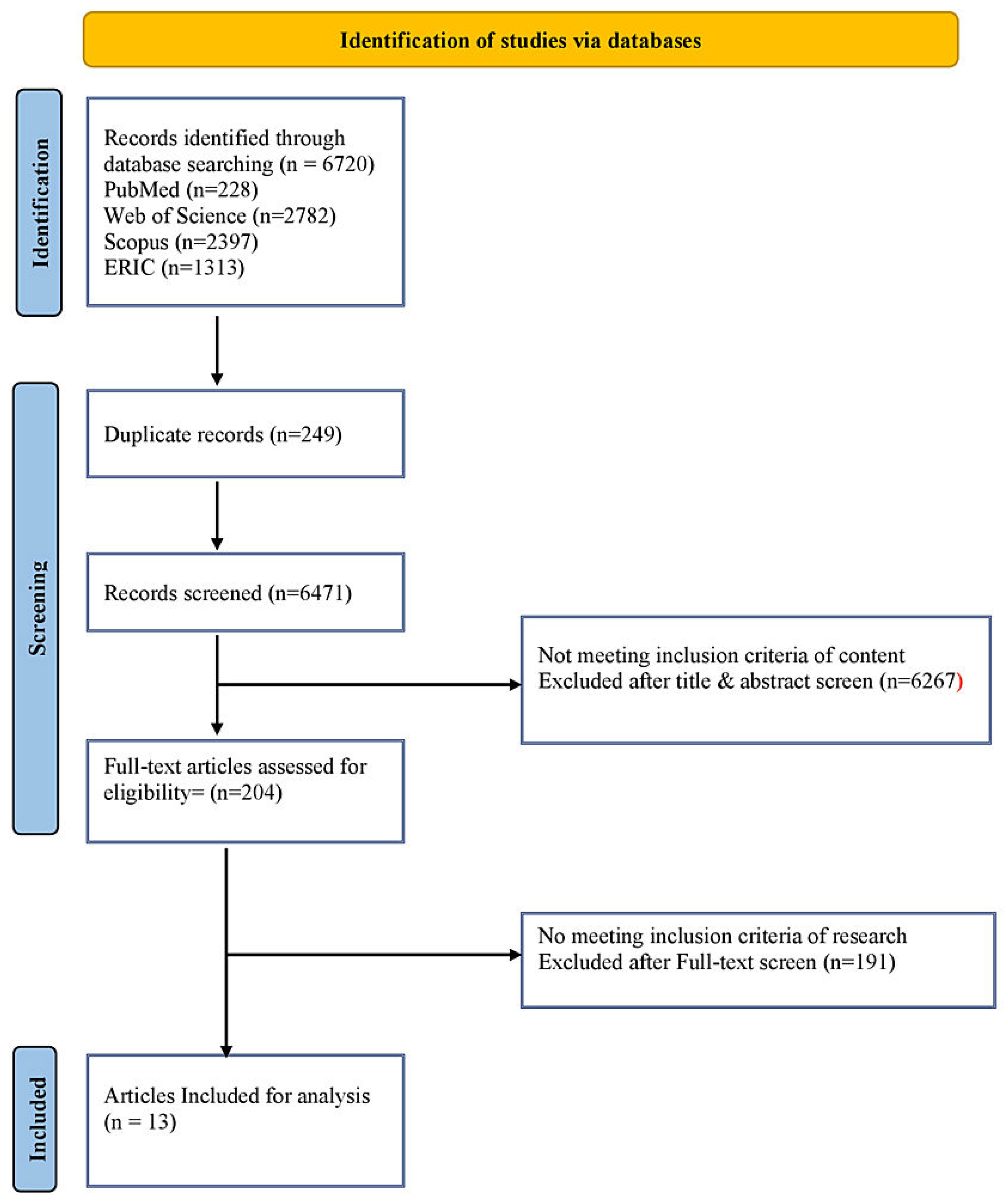

Study selection.

A total of 6,720 articles were identified from the electronic databases. Initially, a total of 249 duplicate records were identified and removed from the dataset to ensure data integrity. The comprehensive search yielded 6,471 records relevant to the research question, which underwent the initial screening process. After careful screening based on titles and abstracts (inclusion criteria of content), many records (n=6,267) were found not to meet the inclusion criteria of content and were consequently excluded from further consideration. Further scrutiny was applied to the remaining records, resulting in the exclusion of all but 204 full-text articles, which were assessed for eligibility in the systematic review. After conducting a thorough full-text screening, 191 articles were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria of the research. Subsequently, a total of 13 articles were deemed eligible and included in the final analysis for this systematic review. A detailed literature search is presented in

Figure 1.

Abbreviations: PubMed, United States National Library of Medicine. ERIC , Education Resources Information Center

This review identified 13 publications that met the eligibility criteria (

Table 2).

Study characteristics.

The findings from the 13 publications reviewed are categorised to three primary categories providing a structured framework for discussing the central evidence identified in the publications. These categories, ‘Teaching Strategy for Pandemic and Challenging Conditions, Tool of Learning and Educational Impact in Medical Education, and Operational Challenges and Future Directions will be used to guide our discussion of the findings.

This table provides a structured framework for understanding the three primary categories identified in the study, each encompassing various aspects related to open-book examinations in medical education.

Discussion

This section review commences by underscoring the adaptability and effectiveness of OBEs during the unprecedented challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting their role in maintaining educational continuity and integrity. Conditions similar to the COVID-19 pandemic that would rationalize the use of open book exams (OBEs) include any situation where traditional, in-person examination methods are impractical or pose health, safety, or logistical issues. These conditions often necessitate a shift towards more flexible, inclusive, and accessible assessment methods that can be administered remotely. This includes public health crises, natural disasters, political or civil unrest and technological disruptions. As we delve deeper, we explore OBEs' enduring utility beyond the pandemic context, examining their impact on student learning strategies, performance, and anxiety levels.

Teaching Strategy for Pandemic and Challenging Conditions

Since the beginning of the year 2020, we have witnessed significant challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. Its global impacts have rippled across all sectors and activities, including education. Social distancing measures became imperative to contain viral transmission, resulting in the abrupt suspension of in-person teaching activities. To prevent potential disruptions, adaptations were made to teaching and assessment methods [

31]. This period of remote learning extended far beyond its initial expectations. This would be applied in all similar scenarios where there are challenges that disrupt traditional examination methodologies (natural disasters, public health crises, political or civil unrest etc). In the following sections, we shall delve into a comprehensive discussion of studies of assessments conducted within this unique context.

Response to the Digital Era and the Pandemic Challenge

Utilization of open-book examinations in distance learning has emerged as a promising approach to adapt to the evolving landscape of education, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. This assessment method aligns well with the principles of remote and online education, where students have access to vast digital resources [

19,

20,

22]. Open-book exams acknowledge the reality that in the era of information abundance, memorization of facts and figures holds less importance compared to the ability to locate, synthesize, and apply knowledge. As such, these assessments emphasize critical thinking, problem-solving, and the practical application of information - skills that are highly relevant in the digital age and future medical practice [

20,

21].

Additionally, the use of open-book exams in distance education offers flexibility and adaptability. This approach enhances the learning experience, promoting active engagement with the content [

23]. Moreover, open-book exams often necessitate continuous engagement with the course material, reinforcing the principles of active learning. In a remote learning environment, where self-directed learning is crucial, open-book exams support students in becoming more independent and resourceful learners [

21]. This is in agreement with Bobby et al [

24] who assessed the effectiveness of "Test enhanced learning" via "open-book examination" as a formative assessment tool in the context of medical education. Most of the students opined that the open-book examination enhanced their self-directed focused learning process. The students felt that open-book examination is more beneficial than “Self-study” in reinforcing the learning concepts after regular didactic lectures.

Efficacy in a remote online setting

During the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the challenges encountered, it presented an excellent opportunity for medical educators to carefully explore the utilization of open-book assessments in an online environment [

31]. This mode of assessment can evaluate students' ability to efficiently research and translate information, a crucial skill requisite for future clinical practice. Furthermore, the same authors advocate for hybrid assessment strategies, including an initial section without access to reference materials to assess the learning of fundamental concepts that students should possess without external aids. Subsequently, a second section permits access to resources, evaluating students' ability to research, synthesize, correlate, construct arguments, and apply clinical reasoning to specific topics.

Eurboonyanun et al. [

20] compared the final-year medical students' online surgery clerkship assessment scores to the traditional written examinations in the previous three rotations, using the same question bank. Students who took the online open-book examination scored higher on average in multiple-choice and essay questions but lower on short-answer questions. This result is important as it highlights the need to establish comparable pass rates and minimum passing grades for assessments with and without open-book access, procedures that should be replicated in other institutions wishing to change their assessment methodologies. Similarly, Sarkar et al. [

21] conducted a study on an online open-book assessment in the otolaryngology discipline, also due to adaptations to remote teaching during the pandemic. The authors compared these results with previous traditional in-person assessments without open-book access and demonstrated similar pass rates in both methodologies.

Student Perspectives

In a study conducted by Elsalem et al. [

19], the findings revealed that only one-third of the students preferred online open-book exams as an assessment modality during the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors attributed this low level of acceptance among students toward open-book assessments to several factors, the need for more effort/time to prepare for online open-book exams, challenges encountered during pre-examination preparations, and perceived disparities between the examination questions and the study materials provided. These findings are valuable for planning academic strategies aimed at effectively addressing the challenges associated with remote open-book assessments. Such strategies may include enhancements in distance learning methods, reorganization of assessment strategies, and review of academic curricula to ensure alignment with the evolving educational landscape.

Academic Integrity

Researchers have raised questions about the occurrence of academic dishonesty or cheating in remote open-book assessments. Elsalem et al. [

19] investigated the occurrence of cheating and dishonesty during these exams and showed that 55.07% of students reported no exam dishonesty or misconduct, while 20.41% mentioned seeking help from friends, and 24.52% used other unauthorized sources of information. Additionally, it is noteworthy that, Sarkar et al. [

21] obtained similar results, with 72.2% of students did not consult with their friends during the examination and answered independently. Monaghan [

22] argues that to safeguard against cheating or collusion, strategies like randomizing the order of questions for each student were employed, rendering communication between them ineffective. This demonstrates that the occurrence of dishonesty and cheating in remote open-book assessments does not appear to be as frequent, and there are methods to discourage such behaviour. However, the current literature lacks studies comparing the frequency of these dishonest actions between in-person and remote assessment methods, as well as comparisons between open-book and closed-book assessments, to determine whether permitting reference materials or open-book access inhibits or reduces the occurrence of cheating.

Operational Challenges and Future Directions

Exam Preparation and Study Strategies

Regarding the influence of the assessment on the preparation and study method, researchers have different opinions. Durning et al. [

11] showed that students do not change their study tactics for open-book examinations. Similarly, Davies [

28] found no difference in preparation time or study tactics for open-book examinations.

In contrast, Sarkar et al. [

21] evaluated student feedback after an online open-book examination and reported that they spent more time understanding the subject rather than just memorizing it. They also realized that they would not be able to write answers to the examination questions if the subjects had not been read and studied beforehand. This may indicate that open-book examinations do not hinder the method of study and preparation, or even better, that student’s study more deeply, focusing less on memorizing concepts and more on higher functions such as correlation, argumentation, and synthesis. This view is shared by Erlich [

29], who emphasizes that in an era of internet-based knowledge evolution, medical professionals and medical students must be competent in quickly accessing, synthesizing, and applying continually updated information for decision-making.

Time Efficiency

In a study conducted by Durning et al. [

11], students took 10% to 60% more time to complete open-book examinations when compared to similar closed-book assessments. These findings are in line with the results of studies carried out in the United States of America. Brossman et al. [

27] reported the need for 40% more time to complete open-book examinations. Studies that evaluated the time required to complete the assessments are in agreement, showing an increase in the time needed for open-book examinations. This finding has direct implications for the implementation of open-book assessments, as the additional time required for completion should be taken into account to ensure that it does not become a factor that negatively influences the assessment outcome [

27].

Anxiety Levels

Other researchers assessed the level of anxiety related to open-book assessments. Sarkar et al. [

21] analyzed student feedback and found a lower level of stress during open-book assessments, in agreement with Prigoff, et al. [

30].

Davies et al. [

28] suggest that anxiety may have played a role in the exam performance, but the researchers did not measure the examinees' anxiety directly. They considered it unlikely that those sitting the open-book exam felt less anxious, given that they had no experience within the course of performing open-book exams and the uncertainty and disruption caused by COVID-19. Furthermore, while examinees may expect themselves to be less anxious in an open-book exam, there is evidence that their experienced anxiety is similar.

However, in Durning et al. [

11], it is observed that students associated open-book assessments with lower anxiety levels, but only a minority of them reported lower anxiety when they performed this type of assessment. Thus, there does not seem to be a consensus on whether students experience reduced anxiety with open-book assessments. However, none of the studies demonstrated an increase in stress or anxiety related to open-book assessments.

Discrimination Power

The power of discrimination in a test or assessment is an index indicating how well the question separates the high-scoring from the low-scoring examinees [

31]. To assess discriminative power, Brossman et al [

27] employed Item Response Theory (IRT), which considers three characteristics of test items: their ability to evaluate whether students have the necessary knowledge to answer them, the level of difficulty, and the likelihood of guessing the correct answer by chance or random guessing. Using this methodology, they demonstrated that open-book assessments have greater discriminative power than similar closed-book assessments. This means that the questions in an open-book assessment have a greater capacity to differentiate high-performing candidates from low-performing ones. This appears to be linked to the depth and complexity of the questions in open-book assessments, which tend to require higher-order thinking skills. At this point, it is worth questioning whether the improved discriminative results are attributed solely to the use of external reference materials or if they are driven by the formulation of questions demanding higher levels of clinical reasoning.

Additionally, it is noteworthy that, Rehman et al. [

23] obtained similar results. The open-book examination was highly discriminatory between high-performing and low-performing students as the majority of the items were found to have moderate [index ranging from 16 to 30) to high discrimination indices of more than 30. Clearly written unambiguous test questions of medium difficulty, which improve the reliability of assessment, are again supportive of these findings.

Limitations and Future Research Direction

There are limitations within this study which need to be acknowledged. One limitation of this study is the relatively limited number of research literature available concerning open-book assessments in medical education, resulting in a small pool of studies included in this review. However, it's worth noting that among these, there are robust and technically sound studies, that allow for important conclusions to be drawn on this subject and provide a foundation for future research initiatives. Therefore, it is anticipated that the insight and knowledge generated in this review will not only stimulate more in-depth discussions on open-book assessments but also serve as a basis for further studies in the future.

Conclusions

There is a clear growing need for appropriate assessment tools, particularly in the biomedical field, to keep bound with the rapid expansion and accessibility of knowledge. These tools should be dynamic, adaptable, and reflective of the evolving landscape of biomedical knowledge. These tools should aim to evaluate not only factual knowledge but also higher-order cognitive skills, critical thinking, and the ability to apply knowledge in practical scenarios.

This review comprehensively examined the current applications of open-book examinations and their integration into medical education. It has presented robust evidence supporting the utilization of remote online open-book assessments, demonstrating their effectiveness, reliability, and compatibility with active teaching methodologies that emphasize student engagement. These assessments enable thorough and high-quality evaluations without compromising their ability to distinguish student performance and reliability. Consequently, they emerge as highly valuable tools for assessing medical students. However, its implementation within medical curricula remains somewhat limited, although it has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, notably through remote examinations on online platforms.

We have highlighted several potential advantages of open-book assessments, as studies show that it contributes to the development of professionals with critical thinking, and problem-solving skills, prepared for lifelong learning and aware of the constant evolution of medical knowledge. However, there are also various challenges associated with this assessment method, including the need to redefine cut-off points and grading criteria, the operational aspects of conducting open-book exams, and the training of both educators and students in using this assessment format.

While open-book examinations in medical education show promise for fostering critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and an appreciation for the evolving nature of medical knowledge, some challenges warrant attention. These include redefining assessment criteria, addressing concerns about academic integrity, and ensuring that such examinations are used complementarily with traditional assessment methods. Therefore, while open-book examinations are a valuable addition to medical curricula, their implementation should be carefully balanced with other forms of assessments to ensure a comprehensive evaluation of student competence.

References

- Boursicot K, Kemp S, Wilkinson T, Findyartini A, Canning C, Cilliers F, et al. Performance assessment: Consensus statement and recommendations from the 2020 Ottawa Conference. Medical Teacher. 2021 Jan 2;43(1):58–67. [CrossRef]

- Pangaro L, ten Cate O. Frameworks for learner assessment in medicine: AMEE Guide No. 78. Medical Teacher. 2018 Jun 1;35(6):e1197–210.

- Myyry L, Joutsenvirta T. Open-book, open-web online examinations: Developing examination practices to support university students’ learning and self-efficacy. Active Learning in Higher Education. 2015 Jul 1;16(2):119–32.

- Epstein, RM. Assessment in Medical Education. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007 Jan 25;356(4):387–96. [CrossRef]

- GMC. Assessment in undergraduate medical education-Tomorrow’s Doctors. General Medical Council-UK; 2018.

- Ben-David, MF. AMEE Guide No. 18: Standard setting in student assessment. Medical Teacher. 2000 Jan 1;22(2):120–30.

- Mahajan R, Saiyad S, Virk A, Joshi A, Singh T. Blended programmatic assessment for competency based curricula. J Postgrad Med. 2021;67(1):18–23.

- Schuwirth LWT, van der Vleuten CPM. How ‘Testing’ Has Become ‘Programmatic Assessment for Learning’. Health Professions Education. 2019 Sep 1;5(3):177–84. [CrossRef]

- Vleuten C, Lindemann I, Schmidt L. Programmatic assessment: the process, rationale and evidence for modern evaluation approaches in medical education. Medical Journal of Australia. 2018 Nov;209(9):386–8.

- Hauer KE, Boscardin C, Brenner JM, van Schaik SM, Papp KK. Twelve tips for assessing medical knowledge with open-ended questions: Designing constructed response examinations in medical education. Medical Teacher. 2020 Aug 2;42(8):880–5.

- Durning SJ, Dong T, Ratcliffe T, Schuwirth L, Artino ARJ, Boulet JR, et al. Comparing Open-Book and Closed-Book Examinations: A Systematic Review. Academic Medicine. 2016 Apr;91(4):583.

- Sam AH, Reid MD, Amin A. High-stakes, remote-access, open-book examinations. Med Educ. 2020 Aug;54(8):767–8.

- Greene J, Mullally W, Ahmed Y, Khan M, Calvert P, Horgan A, et al. Maintaining a Medical Oncology Service during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Irish medical journal. 2020 May 3;11:77.

- Whittemore, R. Combining Evidence in Nursing Research: Methods and Implications. Nursing Research. 2005 Feb;54(1):56. [CrossRef]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;52(5):546–53.

- Yu Xiao, Maria Watson. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 2019 Mar;9(1):93–112.

- Halcomb E, Stephens M, Bryce J, Foley E, Ashley C. Nursing competency standards in primary health care: an integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2016;25(9–10):1193–205.

- CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 6]. CASP Checklists - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- Elsalem L, Al-Azzam N, Jum’ah AA, Obeidat N. Remote E-exams during Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study of students’ preferences and academic dishonesty in faculties of medical sciences. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2021 Feb 1;62:326–33. [CrossRef]

- Eurboonyanun C, Wittayapairoch J, Aphinives P, Petrusa E, Gee DW, Phitayakorn R. Adaptation to Open-Book Online Examination During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(3):737–9.

- Sarkar S, Mishra P, Nayak A. Online open-book examination of undergraduate medical students - a pilot study of a novel assessment method used during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Laryngol Otol. 2021 Apr;135(4):288–92.

- Monaghan, AM. Medical Teaching and Assessment in the Era of COVID-19. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020 Oct 16;7:2382120520965255. [CrossRef]

- Rehman J, Ali R, Afzal A, Shakil S, Sultan AS, Idrees R, et al. Assessment during Covid-19: quality assurance of an online open book formative examination for undergraduate medical students. BMC Medical Education. 2022 Nov 15;22(1):792.

- Bobby Z, Meiyappan K. “Test-enhanced” focused self-directed learning after the teaching modules in biochemistry. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 2018;46(5):472–7.

- Dave M, Patel K, Patel N. A systematic review to compare open and closed book examinations in medicine and dentistry. Faculty Dental Journal [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Oct 10]; Available from: https://publishing.rcseng.ac.uk/doi/10.1308/rcsfdj.2021.41.

- Ibrahim NK, Al-Sharabi BM, Al-Asiri RA, Alotaibi NA, Al-Husaini WI, Al-Khajah HA, et al. Perceptions of clinical years’ medical students and interns towards assessment methods used in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31(4):757–62.

- Brossman BG, Samonte K, Herrschaft B, Lipner RS. A Comparison of Open-Book and Closed-Book Formats for Medical Certification Exams: A Controlled Study. American Educational Research Association; 2017 Apr 28; San Antonio, TX.

- Davies DJ, McLean PF, Kemp PR, Liddle AD, Morrell MJ, Halse O, et al. Assessment of factual recall and higher-order cognitive domains in an open-book medical school examination. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2022 Mar;27(1):147–65.

- Erlich, D. Because Life Is Open Book: An Open Internet Family Medicine Clerkship Exam. PRiMER. 2017 Jul 20;1:7.

- Prigoff J, Hunter M, Nowygrod R. Medical Student Assessment in the Time of COVID-19. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(2):370–4.

- Zagury-Orly I, Durning SJ. Assessing open-book examination in medical education: The time is now. Med Teach. 2021 Aug;43(8):972–3.

- Taha MH, Ahmed Y, El Hassan YAM, Ali NA, Wadi M. Internal Medicine Residents’ perceptions of learning environment in postgraduate training in Sudan. Future of Medical Education Journal. 2019 Dec 1;9(4):3–9.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).