1. Introduction

A decline in swallowing function is a condition in which a disorder occurs somewhere in the series of swallowing processes that causes aspiration, choking, and dehydration [

1]. In older people, a long-term decline in swallowing function can easily lead to malnutrition, and consequently, a reduced quality of life (QOL) [

2]. In Japan, the proportion of older people with a decline in swallowing function has been increasing in recent years, being found in 27.2% of older people in 2020 [

3]. In addition, a decline in swallowing function is often irreversible, making it difficult to return to a normal state, even with treatment [

4]. Therefore, the early detection and control of factors associated with a decline in swallowing function are important for maintaining QOL and of public health significance.

Previous studies have reported a relationship between oral status and swallowing function. For example, impaired swallowing function has been indicated as a potential contributing factor to decreased salivation [

5]. It is also known that impaired swallowing function is associated with a number of

Fusobacterium spp., one of the bacteria associated with periodontal disease [

6]. Furthermore, dysphagia is part of oral dysfunction, as all oral functions are interrelated and used to assess frailty in older people [

7]. However, because these observations are based on cross-sectional studies, whether oral factors contribute to a future decline in swallowing function in older people remains unclear.

Dental checkups in Gifu, Japan (

Gifu sawayaka koku kenshin) are conducted once a year for Japanese older people aged ≥ 75 years [

8,

9]. This checkup also includes content related to swallowing function. Therefore, a longitudinal study of these data may make it possible to search for factors that predict a future decline in swallowing function. In the present study, we hypothesized that some dental checkup items might be associated with a future decline in swallowing function. Therefore, we conducted a longitudinal study over a 2-year period with the aim of clarifying the longitudinal associations between dental checkup items and a decline in swallowing function in Japanese older people aged ≥ 75 years.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

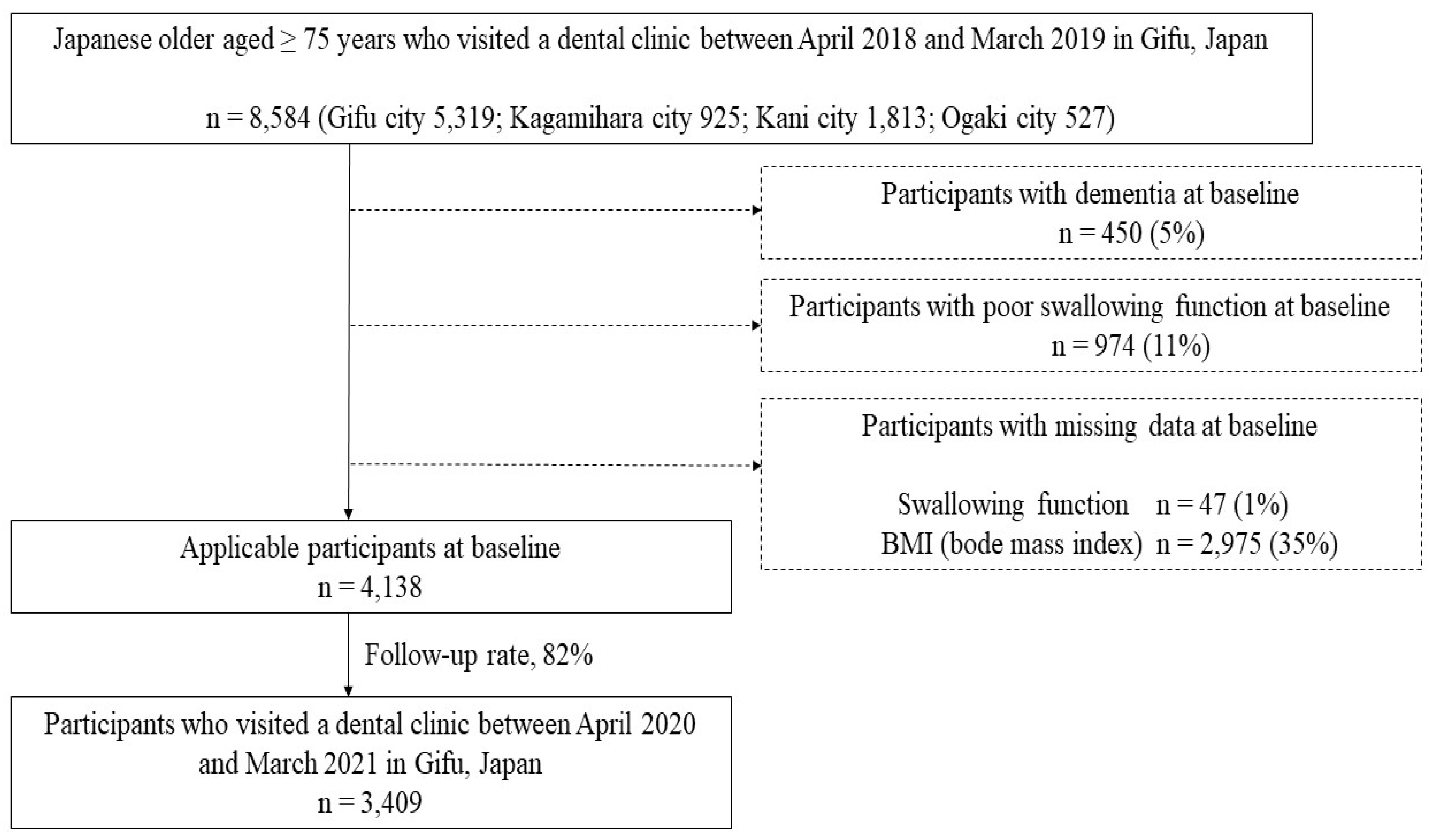

Data were analyzed from local residents who had undergone a dental checkup in Gifu city, Kagamihara city, Kani city, and Ogaki city in Gifu Prefecture, Japan. Between April 2018 and March 2019, a total of 8,584 Japanese older people aged ≥ 75 years participated in the baseline survey. Participants with dementia (n = 450) and those showing a decline in swallowing function at baseline (those who could not swallow at least three times in 30 second in a repetitive saliva swallowing test [

10]; n = 974) were excluded. Participants with missing data on swallowing function (n = 47) and body mass index (BMI) (n = 2,975) were also excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 4,138 participants, 3,409 were followed from April 2020 to March 2021 (follow-up rate: 82%). Therefore, data from 3,409 community-dwelling residents (1,428 males and 1,981 females; mean age at baseline: 81 years) were analyzed in the present study (

Figure 1).

Checkup Items by Dentists

Data on the following dental checkup items by dentists were collected: swallowing function, presence or absence of ≥ 20 present teeth, presence or absence of decayed teeth, and presence or absence of a periodontal pocket depth (PPD) ≥ 4 mm. The data for the dental checkup items were provided by the Gifu Dental Association, Japan. For swallowing function, patients who could not swallow at least three times in 30 second in a repetitive saliva swallowing test were evaluated as having a decline in swallowing function [

10]. The coded values of the Community Periodontal Index were used to evaluate PPD ≥ 4 mm, with codes 1 and 2 being evaluated as PPD ≥ 4 mm [

11].

Self-Administered Questionnaires Items

Data on difficulty in biting hard food, choking on tea and water, dry mouth, and smoking habits were provided by the Gifu Dental Association, Japan. On the self-administered questionnaire, the participants were asked to choose “yes” or “no” for the following items: “I have difficulty biting hard food”, “I choke on tea and water”, and “I have dry mouth” [

12]. Regarding smoking habits, participants who smoked at least one cigarette per day were included (presence or absence) [

13].

Survey Items in the National Health Insurance Database System

Data on gender, age, BMI, and presence or absence of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, musculoskeletal disorders, and support/care-need certification were obtained from the National Health Insurance Database of Japan (NDB) [

14,

15].

Statistical Analysis

Differences in the participants’ characteristics at baseline and after 2 years were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed with the presence of a decline in swallowing function as the dependent variable. In multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis, in addition to gender and age, variables that were significantly different in the univariate logistic regression analysis were selected as confounders and set as adjustment variables. We confirmed the suitability of this model using the Hosmer–Lemeshow fit test. These data were then analyzed using SPSS statistical analysis software (version 27; IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). All p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Asahi University (No. 33006) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Brazil 2013).

3. Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants at baseline and after 2 years. The proportions of participants with hypertension (p = 0.009), diabetes (p = 0.008), musculoskeletal disorders (p = 0.005), and support/care-need certification (p < 0.001) were significantly higher after 2 years than at baseline. In addition, the proportion of participants with ≥ 20 present teeth were significantly lower after 2 years than at baseline (p < 0.001). However, no significant differences in decayed teeth, PPD ≥ 4 mm, difficulty in biting hard food, choking on tea and water, and dry mouth were found between at baseline and after 2 years.

Table 2 shows the crude odds ratios [ORs] and 95% confidence intervals [CIs] for a decline in swallowing function after 2 years. In the present study, 429 participants (13%) were newly diagnosed with a decline in swallowing function after 2 years. The results indicated that the risk of a decline in swallowing function after 2 years was significantly correlated with male gender (ORs: 0.711; 95% CIs: 0.550–0.918), age ≥ 81 years (presence; ORs: 1.834; 95% CIs: 1.493–2.251), musculoskeletal disorders (presence; ORs: 1.419; 95% CIs: 1.102–1.828), support/care-need certification (presence; ORs: 2.743; 95% CIs: 2.121–3.546), decayed teeth (presence; ORs: 1.319; 95% CIs: 1.058–1.645), PPD ≥ 4 mm (presence; ORs: 1.424; 95% CIs: 1.137–1.784), difficulty in biting hard food (yes; ORs: 1.907; 95% CIs: 1.538–2.365), choking on tea and water (yes; ORs: 3.020; 95% CIs: 2.436–3.744), and dry mouth (yes; ORs: 1.844; 95% CIs: 1.497–2.272) at baseline.

Table 3 shows the adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for a decline in swallowing function after 2 years. After adjusting for gender, age, musculoskeletal disorders, support/care-need certification, decayed teeth, PPD, difficulty in biting hard food, choking on tea and water, and dry mouth, the risk of decline in swallowing function after 2 years was significantly correlated with male gender (ORs: 0.772; 95% CIs: 0.615–0.969), age ≥ 81 years (presence; ORs: 1.523; 95% CIs: 1.224–1.895), support/care-need certification (presence; ORs: 1.815; 95% CIs: 1.361–2.394), PPD ≥ 4 mm (presence; ORs: 1.469; 95% CIs: 1.163–1.856), difficulty in biting hard food (yes; ORs: 1.439; 95% CIs: 1.145–1.808), choking on tea and water (yes; ORs: 2.543; 95% CIs: 2.025–3.193), and dry mouth (yes; ORs: 1.316; 95% CIs: 1.052–1.646) at baseline.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to examine the associations between dental checkup items and a decline in swallowing function in Japanese older people. The results of a logistic regression analysis showed that, after adjusting for gender, age, musculoskeletal disorders, support/care-need certification, decayed teeth, PPD, difficulty in biting hard food, choking on tea and water, and dry mouth, the presence or absence of a decline in swallowing function after 2 years was associated with PPD ≥ 4 mm, difficulty in biting hard food, choking on tea and water, and dry mouth at baseline. From these results, having PPD ≥ 4 mm, difficulty in biting hard food, choking on tea and water, and dry mouth were predicted to be associated with a higher risk of a decline in swallowing function in the future.

Previous studies have reported a relationship between a decline in swallowing function and overall health, showing that dysphagia was associated with diabetes and the development of dementia [

16,

17]. A decline in swallowing function has also been reported to be associated with malnutrition and future mortality [

18]. These reports indicate that a decline in swallowing function could be detrimental to overall health. In addition, once swallowing function declines, it is difficult to return to the original state [

4]. Therefore, early screening to prevent a decline in swallowing function through dental checkups is important for the maintenance and promotion of overall health. However, early dental intervention may be necessary, especially for those with factors found to be associated with a decline in swallowing function during dental checkups.

Previous studies have reported that poor chewing function in older people reduces the ability to form and retain a food bolus and contributes to a decline in swallowing function [

19]. It has also been reported that decreased salivation causes a decline in swallowing function [

20]. These previous observations are consistent with the present results, which indicated that difficulty in biting hard food, choking on tea and water, and dry mouth were associated with a decline in future swallowing function according to a self-administered questionnaire using data from dental checkups. Furthermore, the previous diagnoses were self-reported, not based on specialized knowledge or instruments. In other words, these factors can be noticed by one’s own senses, regardless of whether one has undergone a dental checkup. The results of the present study suggest that if a person is aware of a difficulty with chewing hard foods, choking on tea or water, or dry mouth, they should undergo a dental checkup or visit a dental clinic to help prevent a decline in swallowing function.

The results of the present study indicated that a PPD ≥ 4 mm is a risk factor for a decline in swallowing function. A previous epidemiological study reported that approximately 56% of older patients with a decline in swallowing function had periodontal disease [

21]. Another study reported that people with a decline in swallowing function possess greater amounts of periodontal disease-associated bacteria (such as

Fusobacterium spp.) than do those with normal swallowing function [

6]. The present and these previous studies are consistent in that they all found that periodontal disease is associated with a decline in swallowing function.

In Japan, based on the Long-Term Care Insurance Law, people who require daily and continuous support and care because of various disabilities can receive support/care-need certification [

22]. This certification can then be classified into seven types, starting with those with minor illnesses, namely, support-need certification 1–2 and care-need certification 1–5 [

22]. The results of the present study indicated that support/care-need certification is a risk factor for a decline in swallowing function. This observation is in agreement with previous studies reporting that a significantly higher proportion of people with support/care-need certification had a decline in swallowing function compared with those without support/care-need certification [

23,

24]. Therefore, the present and previous studies support the need for measures to prevent a decline in swallowing function precisely for those with support/care-need certification.

In the present study, we evaluated multivariate logistic regression analysis models using the Hosmer–Lemeshow fit test. The Hosmer–Lemeshow fit test is used to examine the fit of a multivariate logistic regression analysis model and tests whether the observed event rate in a subgroup model fits the expected event rate. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test is considered to fit well with

p-values > 0.05 [

25]. In the present study, the

p-value was 0.432, suggesting that it fit well.

However, this study has several limitations. First, because the participants underwent regular dental checkups (at least once in both 2018 and 2020), they may have been a more health-conscious sample than the general population. Therefore, if different health populations are targeted, the results may differ. Second, because the NDB was used, the presence or absence of diseases and disorders not in the database were unknown. On the other hand, a major strength of this study is that it was a longitudinal study of more than 3,400 Japanese older people aged ≥ 75 years, which is useful for establishing causal associations with a decline in swallowing function. Furthermore, it was possible to gather study population data from multiple areas in Japan (Gifu city, Kagamihara city, Kani city, and Ogaki city).

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study indicate that among dental checkup items, PPD ≥ 4 mm, difficulty in biting hard food, choking on tea and water, and dry mouth are associated with a higher risk for a future decline in swallowing function among Japanese older people aged ≥ 75 years. PPD status and confirming to the self-administered questionnaire about biting, choking, and dry mouth may be useful in predicting future decline in swallowing function.

Author Contributions

The present study was carried out with the collaboration of all authors. K.I., T.A., and T.T. conceived the study. T.A., T.Y., Y.S., T.K., K.T., T.N., I.S., Y.I., Y.M., S.N., and Y.A. collected the data. K.I. and T.T. analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Review Committee of Asahi University (protocol code 33006).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Gifu National Health Insurance Federation and Wide-Area Federation of Medical Care for Late-Stage Older People, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the present study and are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the Gifu National Health Insurance Federation and Wide-Area Federation of Medical Care for Late-Stage Older People.

Acknowledgments

This study was self-funded by the authors and their institution. The authors are grateful to the Gifu National Health Insurance Federation and the Wide-Area Federation of Medical Care for Late-Stage Older People for providing the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rajati, F.; Ahmadi, N.; Naghibzadeh, A.Z.; Kazeminia, M. The global prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in different populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Transl Med. 2022, 20, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christmas, C.; Rogus-Pulia, N. Swallowing disorders in the older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019, 67, 2643–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2020. [Accepted March 26 2024]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000711005.

- Paterson, G.W. Dysphagia in the elderly. Can Fam Physician. 1996, 42, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maarel-Wierink, C.D.; Vanobbergen, J.O.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Schols, A.; Baat, C. Oral health care and aspiration pneumonia in frail older people: a systematic literature review. Gerodontology. 2013, 30, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morino, T.; Okawa, K.; Hagiwara, Y.; Seki, M. Relationship between decreased swallowing function and oral hygiene status in elderly people requiring care who currently have teeth. J Dent Hlth. 2012, 62, 478–483. [Google Scholar]

- Robison, R.; Garand, L.K.; Affoo, R.; Yeh, C.; Chin, N.; McArthur, C.; Pulia, M.; Rogus, N. New horizons in understanding oral health and swallowing function within the context of frailty. Age Ageing. 2023, 52, afac276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, K.; Azuma, T.; Yonenaga, T.; Sasai, S.; Nomura, T.; Sugiura, I.; Inagawa, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Nakashima, S.; Abe, Y.; Tomofuji, T. Longitudinal association of oral functions and dementia in Japanese older adults. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Wide-Area Federation of Medical Care for Late-Stage Older People. Gifu SAWAYAKA Oral Health Checkup [Accepted March 14 2024]. Available from: https://www.gikouiki.jp/seido/medical-checkup/.

- Tamura, F.; Mizukami, M.; Ayano, R.; Mukai, Y. Analysis of feeding function and jaw stability in bedridden elderly. Dysphagia. 2002, 17, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Oral health surveys, basic methods, 5nd edition; World Health Organization Publishers, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto, K.; Kiuchi, S.; Takeuchi, K.; Kusama, T.; Nakazawa, N.; Tamada, Y.; Aida, J.; Kondo, K.; Osaka, K. Oral status and incident functional disability: A 9-year prospective cohort study from the JAGES. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023, 111, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, Q.; Shereen, A.; Estabraq, M.; Jood, S.; Abdelfattah, A.T.; Adil, A. Electronic cigarette among health science students in Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2019, 14, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Iwai, K.; Azuma, T.; Yonenaga, T.; Nomura, T.; Sugiura, I.; Inagawa, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Nakashima, S.; Abe, Y.; Tomofuji, T. Relationship between oral function and support/care-need certification in Japanese older people aged ≥ 75 years: a three-year cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 16959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagakura, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Kajioka, S. Lifestyle habits to prevent the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia: analysis of Japanese nationwide datasets. Prostate Int. 2022, 10, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, A.D.; Bekhet, M.M.; Khodeir, S.M.; Bassiouny, S.S.; Saleh, M.M. Oropharyngeal dysphagia and diabetes mellitus: screening of 200 type 1 and type 2 patients in Cairo, Egypt. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2018, 70, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sura, L.; Madhavan, A.; Carnaby, G.; Crary, A.M. Dysphagia in the elderly: management and nutritional considerations. Clin Interv Aging. 2012, 7, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rommel, N.; Hamdy, S. Oropharyngeal dysphagia: manifestations and diagnosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016, 13, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmae, Y. Changes in swallowing function with aging. Speech and language medicine. 2013, 54, 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Arany, S.; Kopycka-Kedzierawski, T.D.; Caprio, V.T.; Watson, E.J. Anticholinergic medication: Related dry mouth and effects on the salivary glands. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2021, 132, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, O.; Parra, C.; Zarcero, S.; Nart, J.; Sakwinska, O.; Clavé, P. Oral health in older patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Age Ageing. 2014, 43, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Health and Welfare Division for the Elderly: Mechanism and procedure for support/care-need certi-fication [Accepted March 26 2024]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-11901000-Koyoukintoujidoukateikyoku-Soumuka/0000126240.

- Takeuchi, K.; Aida, J.; Ito, K.; Furuta, M.; Yamashita, Y.; Osaka, K. Nutritional status and dysphagia risk among community-dwelling frail older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014, 18, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, A.; Ishizaka, M.; Sawaya, Y.; Shiba, T.; Urano, T. Relationship between the swallowing function, nutritional status, and sarcopenia in elderly outpatients. J Geriatr Society. 2021, 58, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied logistic regression, 2nd edition; John Wiley and Sons, 2000. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).