Introduction

The field of Learning Sciences (LS) continues to evolve as an academic discipline and community. Over the past 30 years, LS has gained increasing attention among academics and scientists, and many universities around the globe now offer graduate programs in learning sciences. Yet, little is known about how the increasingly multidisciplinary nature of LS and how socio-environmental factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic or the call for more equity-based research are changing LS practices, methods, or disciplines of interest. At its core, LS is multifaceted and characterized by the integration of diverse scientific disciplines, each contributing to research on learning and supporting learning in the real world (Sommerhoff et al., 2018). LS brings together scientists from different backgrounds like psychology, design studies, computer science, cognitive sciences, and medical sciences. These scientists adopt varying theories and methods to support and make sense of how people teach and learn (Hoadley, 2018).

Knowing the extent to which learning sciences methods and practices have evolved might be crucial to understanding the current status of the learning sciences and its future development, which might depend on the evolving diverse methods that future scientists across disciplines adopt (Nathan et al., 2016). The current study aims to investigate the evolving trends in the learning sciences across several years and thereby extend existing studies that have examined the territory (Packer & Maddox, 2016), curricula (Sommerhoff et al., 2018), and nature (Nathan et al., 2016; Sawyer, 2014) of the learning sciences. We examined trends in LS regarding methods, practices, domains of interest, techniques, participants, and alignment with contemporary ideas like promoting equity and inclusion.

Specifically, we set out to answer the broad question: what are the trends in learning sciences research from 2005 to 2021? To answer this question, we explored proceedings in the International Society of Learning Sciences (ISLS) repository from 2005 to 2021. ISLS is a professional community dedicated to expanding the impact and relevance of learning science research. Its annual meeting brings academics, professionals, and students from the learning sciences and the Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) community. It remains the primary venue for learning sciences and CSCL researchers to share and publish their work and new ideas about learning across multiple contexts.

Literature

This section examines some characteristics of the Learning Sciences (LS) as an academic field and a community. Based on Sommerhoff et al. (2018) study, we discussed five core features of the learning sciences that distinguish it as a discipline.

LS as a Discipline

According to Sommerhoff et al. (2018), LS uses theoretical approaches to understand how children and adults develop new knowledge and make sense of their world (Sommerhoff et al., 2018). Theories employed by learning scientists usually emphasize the physical, social, and at times emotional context of cognition that allows learners to accomplish authentic and meaningful tasks. Similarly, learning scientists often focus on understanding how learning occurs in specific contexts and disciplines like mathematics, sciences, arts, and computer science (Tabak & Radinsky, 2015). The third feature of LS is its focus on supporting learning through the use of innovative pedagogical practices like scaffolding, problem-based learning, and project-based learning (Sawyer, 2014) and the design of rich learning environments like games and simulations. Relatedly, LS research also emphasizes using technology and multimedia to enhance learning and collaboration. As digital technology continues to drive society, learning scientists are increasingly examining the effect of technology on human learning and behavior.

Finally, LS uses a broad range of methods to develop theories and investigate questions related to how people learn and behave. Diverse methods shape LS due to its multidisciplinary nature (Hoadley & Van Haneghan, 2011). Learning scientists are interested in understanding the amount of learning that took place and how learning occurred, including the processes, activities, and environmental factors that facilitate or inhibit learning. For this reason, design-based research is a common method among learning scientists (Sawyer, 2014), as the method allows researchers to use an iterative process when attempting to understand the complex exchanges and outcomes that occur as learners interact with other variables in the learning environment. Other methods commonly used in the learning sciences include participatory design, qualitative, and mixed methods (Hoadley, 2018).

Methods

Data Collection

To examine the evolving trends in LS research, we scraped data from the ISLS repository (

https://www.isls.org/) using the Web Scraper tool (

https://webscraper.io/). Web Scraper works as a developer tool within the browser console, and it allows researchers to scrape data across several pages through its crawler and sitemaps. We created site maps for each proceeding year using Web Scraper (see

Figure 1). Once the site maps were created and guided to navigate from the web pages into each article page metadata (See

Figure 2) we pulled all available proceeding data from the ISLS repository from 2005 to 2021. Prior to 2021, ISLS publishes the ICLS and ISLS proceedings on alternate years such that ICLS proceedings were published on even years (e.g. 2006, 2008, 2010, etc.) while CSCL publications were published in odd years (2005, 2007, 2009, etc.). However, in 2021, both proceedings were published together, marking the first time when both conferences and proceedings occurred simultaneously.

To answer our research question, we pulled the following variables from the ISLS repository, (a) title, (b) abstract, (c) issue_date, (d) publisher, (e) abstract and (f) collection. Since the abstracts of the articles were very important for data analysis, we only scraped data from proceeding years with an abstract on the article metadata page. The articles published from 1995 - 2004 and 2011 fell into the category without an abstract on the metadata web page and were therefore omitted from the data. Once the data has been scraped, Web Scraper allows the users to download it as a json or spreadsheet. At the end of the web scraping process, we had a total of 3,689 ICLS and CSCL articles published between 2005 and 2021.

Data Analysis

The 3,689 collected articles were analysed using “Rstudio”. RStudio is a free and open-source integrated development environment (IDE) for R programming language. R is used for statistical computing and allows researchers to explore and analyze patterns within a dataset using statistical methods like text analysis, and regression. Within RStudio, we first cleaned the dataset using the {janitor} and {tidyverse} package to make the variables consistent across each year. Next we read through the abstract to identify concepts that were prevalent across the years. To aid our understanding of the data, we performed an initial key word analysis of the publication titles and abstract, and generated word clouds that visualized the distribution of concepts in the data (see Appendix 1).

Based on this preliminary analysis and existing LS literature, we narrowed on the LS trends to examine the data. Specifically, we investigated methods, domains or disciplines, population of interest, and practices relative to the following key words: (a) methods - “design-based” research, “collaborative” research, “participatory” research, (b) practices - problem-based, project-based, embodied learning, game-based (c) domains - “science”, “mathematics”, “arts”, “engineering”, “technology”, (d) population - “teachers” and “students.” Additionally, we examined the data for evidence of LS promotion of equity using the regular expression “equity|equit|diversity|inclusion|inclusive.” The key words expressions are not yet validated but they will be validated in future works. Finally, we analyzed and visualized the trends within the data using graphs and summary tables. The findings of our analysis are presented in following section.

Findings

Methods and Practices in Learning Sciences

In our analysis, we attempt to examine research methods and practices that LS studies have adopted over the last fifteen years.

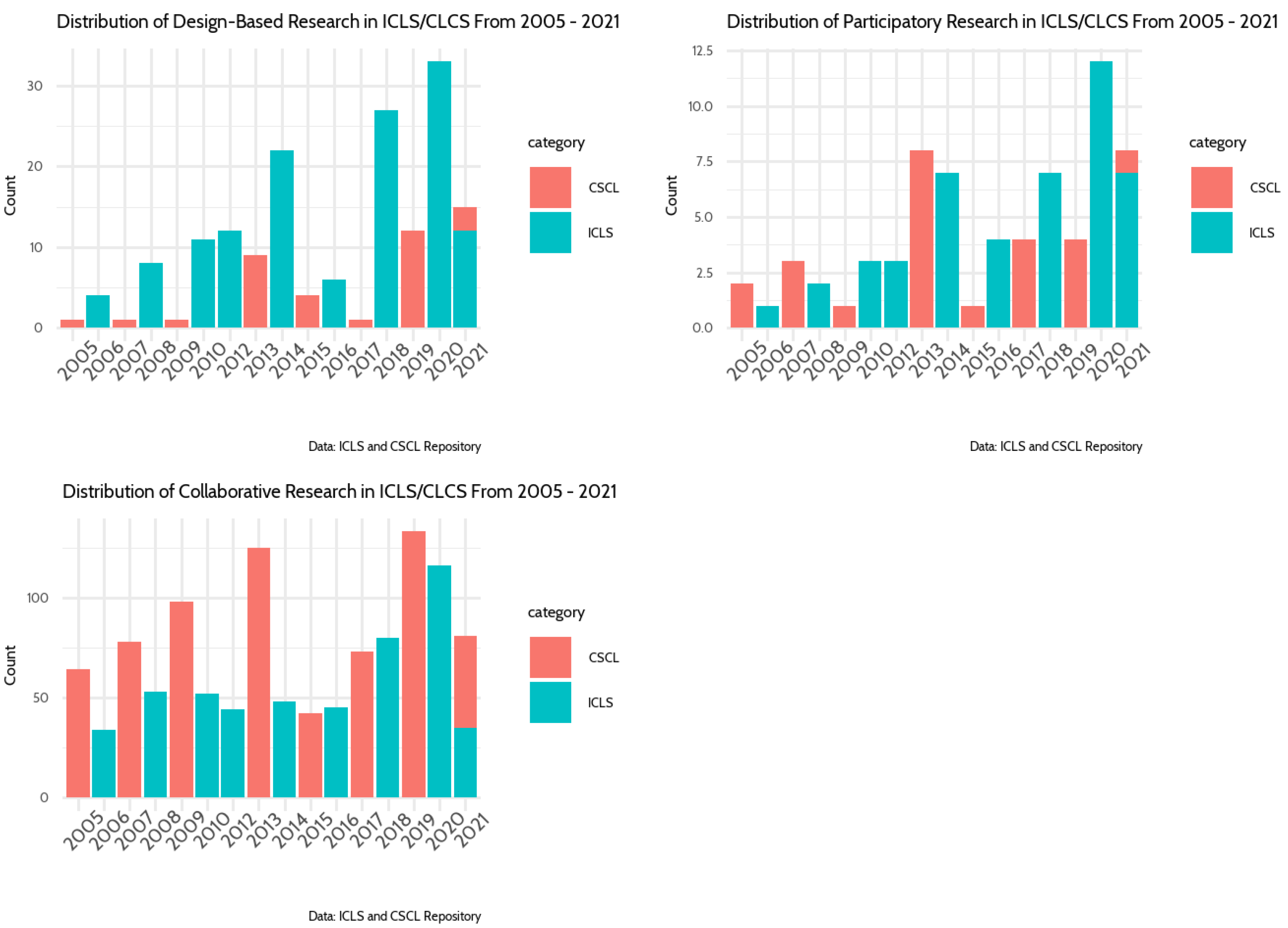

Figure 3 reveals that ICLS studies use Design-based research (DBR) and Participatory methods more than CSCL studies. From year 2005 to 2020 there was a large increase in the adoption of DBR studies in the LS community. However, there was a sharp decline from 2020 to 2021. Conversely, collaborative research method were unsurprisingly popular among CSCL research from 2005 to 2006. However, from 2007 ICLS research appears to begin adopting this method and by 2021 there seems to be no observable difference in the number of CSCL and ICLS studies using collaborative research methods.

With regards to LS practices, Findings showed that project-based learning, embodied interaction, and game-based learning are the most frequently used techniques among ISLS researchers. The usage of embodied and game-based learning strategies increased steadily between 2005 and 2012 (see Appendix 2). However, it appears from 2013 to 2021, adoption rates significantly increased. Project-based learning was used in more research during this time period. Problem-based learning has been used consistently over time, but it has yet to gain widespread adoption like the other three strategies have.

Participants and Domain focus among LS Studies

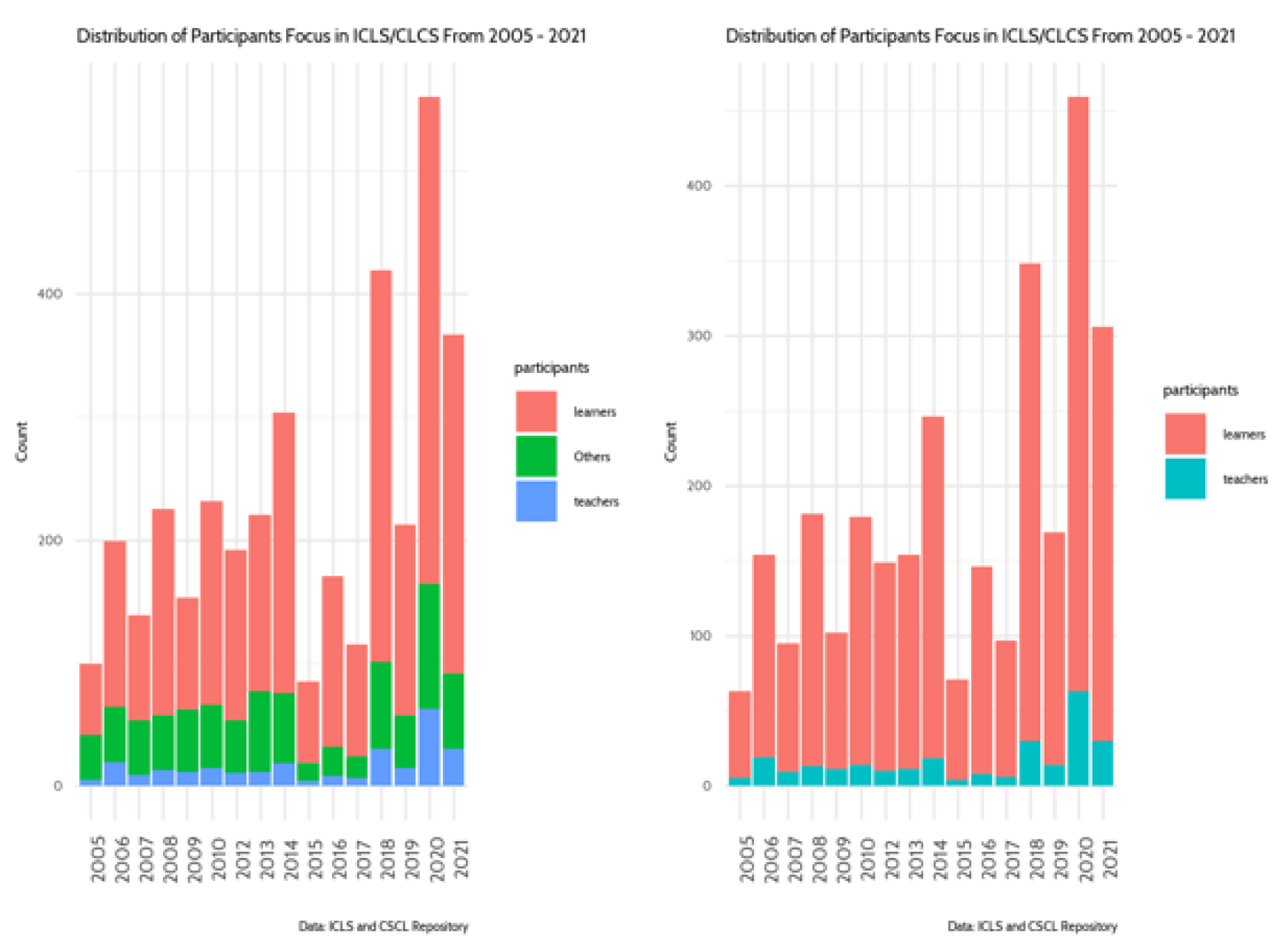

To examine the population focus of ICLS and ISLS studies over the years our population of interest include: learners, teachers, and others (including researchers, community members, etc.). We filtered for studies that focused on young learners using regular expressions like “student|learner,” “children|youth,” and “girl|undergrad|boy”, for teachers, we looked out for “teacher|educator”, and other studies who did not fit this category are grouped as others.

Figure 4 shows how extensively learner-focused ICLS and CSCL research has been. The number of research primarily supporting instructors remains very low compared to those focused on student learning. Moreover, the sparse teacher-focused research did not change significantly between 2005 and 2017. Whereas, the number of research focusing on students increased dramatically throughout this time. From 2018 to 2021 there appears to be an increase in the number of studies focusing on teachers, although learners were still the primary focus during this period.

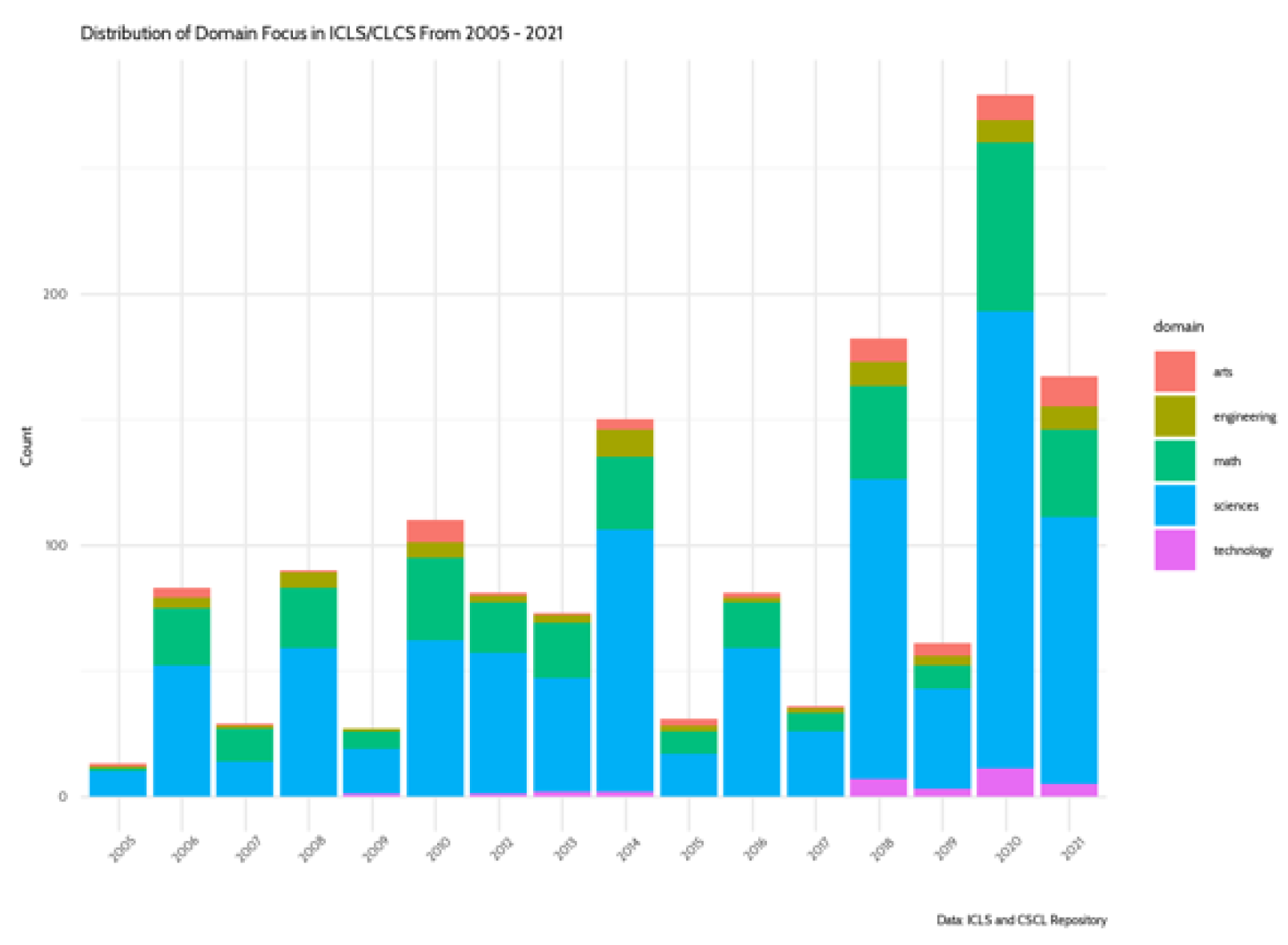

We also examined the subject discipline focus of ICLS and ISLS studies over the years. Our groupings include: science, art, math, engineering, technology and others. After filtering for relevant keywords, we decided to exclude the “others” category, to allow for more focus in our interpretations. From

Figure 5 we observe that Sciences, followed by Mathematics have been the primary disciplines of LS research over the years. From 2005 to 2017, the studies were primarily focused on science and mathematics disciplines, and some bit of engineering studies. Arts disciplines also appeared during this period but not that prevalent.

However, since 2018, there appears to be an increase in the number of studies focusing on the arts and technology. Finally,

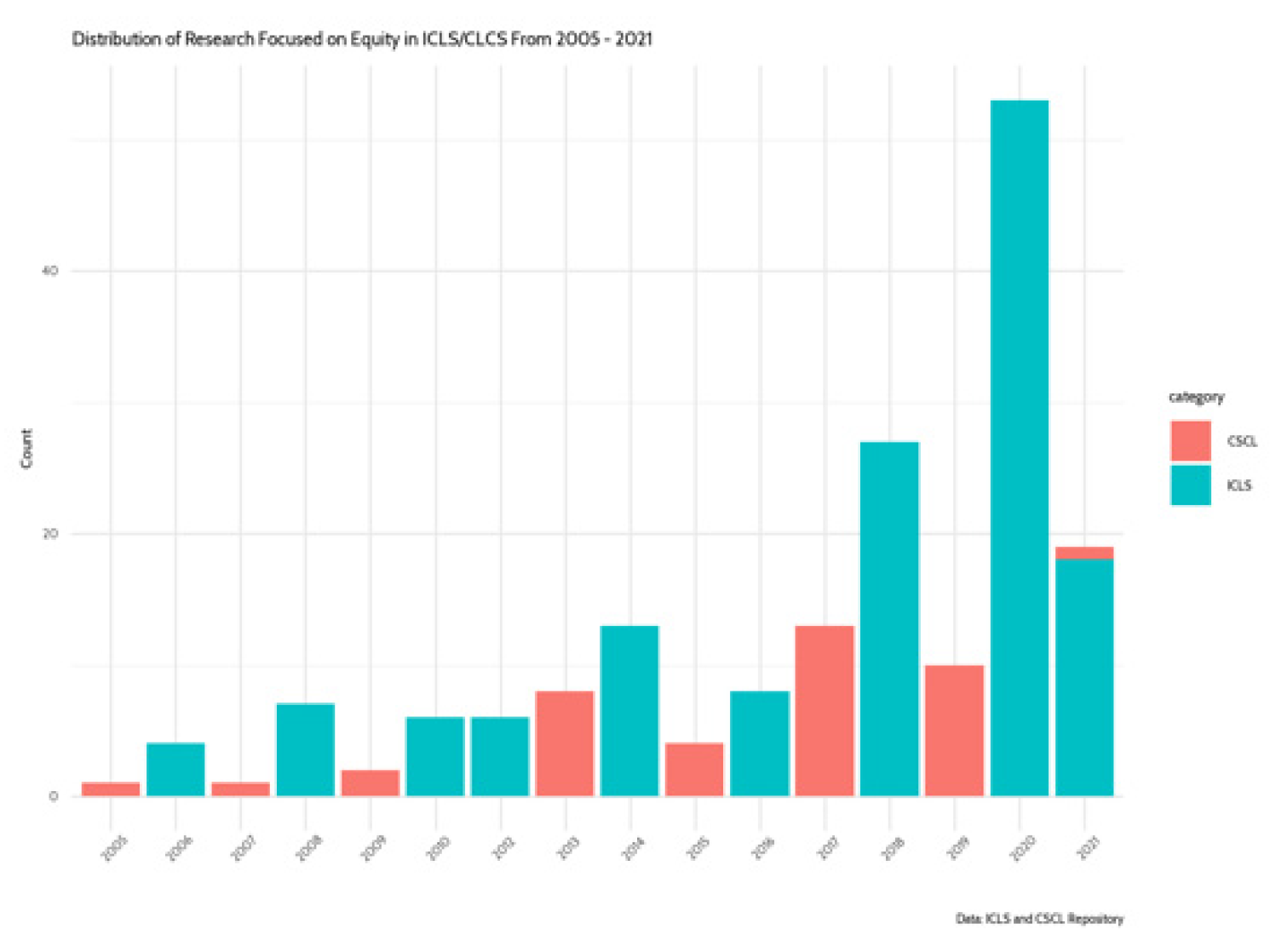

Figure 6 showed that studies focused on promoting equity have witnessed a significant increase from 2005 to 2021, with the peak during 2020. From the graph, ICLS studies tended to focus more on equity compared to CSCL studies. From 2005 to 2020 there was a steady increase in equity research, however, there was a sharp decline in 2021.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study we examined how the Learning Sciences have evolved in terms of methods, disciplines, practices, population of interest, and the promotion of equity. Generally, the distribution of submissions showed that the field of LS has grown significantly over the years, with the peak year being 2020 for ICLS research/paper and 2013 being the peak for CSCL papers. The sharp decline in 2021 submissions might be due to the COVID-19 pandemic as many people were addressing different physical, mental and family issues that limited the amount of submission during the pandemic. CSCL submissions were generally lower than ICLS submissions, suggesting that studies focused on developing computational tools and computer supported environments have not witnessed similar attention like those focused on theories and approaches in the LS. With regards to methods, design-based research (DBR) and Participatory research remain the most popular among LS researchers across the years under study. This aligns with current literature that identify DBR as a primary method in the LS community (Sommerhoff et al., 2014). Similarly, the sharp decline in the use of both methods in 2021 might be due to the effects of the pandemic which limited researchers’ ability to conduct field studies in real settings. Finally, although LS research continues to be heavily learner-centred and more focused on math and science field, there seems to be an increasing attention to teacher-related studies and art and engineering-based disciplines.

Conclusion and Future Work

This work in progress examined the trends (methods, practices, disciplines, population, and equity) in LS research and community. The findings are preliminary and limited by (a) our reliance on only the abstract and titles of ISLS proceedings across the years under study, and (b) the unvalidated regular expressions that determined what counts as evidence of a concept or idea in the study. In future works, we intend to validate the filtering criteria to make them more representative, explore a network analysis of LS authors over the period under review, and examine additional methods and practices that might have been omitted during our analysis.

References

- Booker, A., Vossoughi, S., & Hooper, P. (2014). Tensions and possibilities for political work in the learning sciences. In J. Polman, E. Kyza, D. K. O’Neill, I. Tabak, W. R. Penuel, A. S. Jurow, T. Lee, & L. D’Amico (Eds.), International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS) 2014, Volume 2. Boulder, CO: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

- Hoadley, C. (2018). A short history of the learning sciences. In In F. Fischer, C. E. Hmelo-Silver, S. Goldman, & P. Reimann (Eds.), International handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 11-23). Routledge.

- Hoadley, C., & Van Haneghan, J. (2011). The learning sciences: Where they came from and what it means for instructional designers. In R. A. Reiser, & J. V. Dempsey (Eds.), Trends and issues in instructional design and technology (Vol. 3, pp. 53–63). New York, NY: Pearson.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Nathan, M. J., Rummel, N., & Hay, K. E. (2016). Growing the learning sciences: Brand or big tent? Implications for graduate education. In M. A. Evans, M. J. Packer, & R. K. Sawyer (Eds.), Reflections on the learning sciences (pp. 191–209). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Packer, M. J., & Maddox, C. (2016). Mapping the territory of the learning sciences. In M. A. Evans, M. J. Packer, & R. K. Sawyer (Eds.), Reflections on the learning sciences (pp. 126–154). Cambridge University Press.

- Sawyer, R. K. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. Cambridge University Press.

- Sommerhoff, D., Szameitat, A., Vogel, F., Chernikova, O., Loderer, K., & Fischer, F. (2018). What do we teach when we teach the learning sciences? A document analysis of 75 graduate programs. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 27(2), 319-351. [CrossRef]

- Tabak, I., & Radinsky, J. (2015). Paving new pathways to supporting disciplinary learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 24(4), 501–503. [CrossRef]

- Uttamchandani, S. (2018). Equity in the learning sciences: Recent themes and pathways. Proceedings of the International Society of the Learning Sciences [ISLS]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).