Submitted:

25 April 2024

Posted:

25 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methodology

Data Collection

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Data Extraction

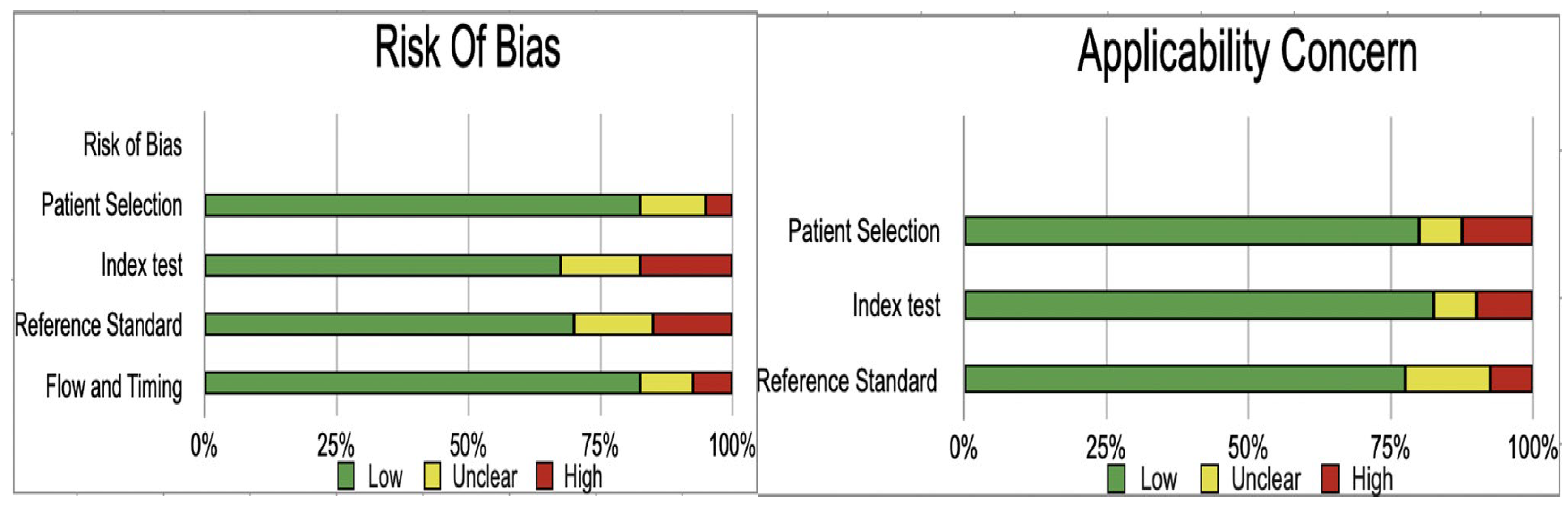

Assessment of Study Quality

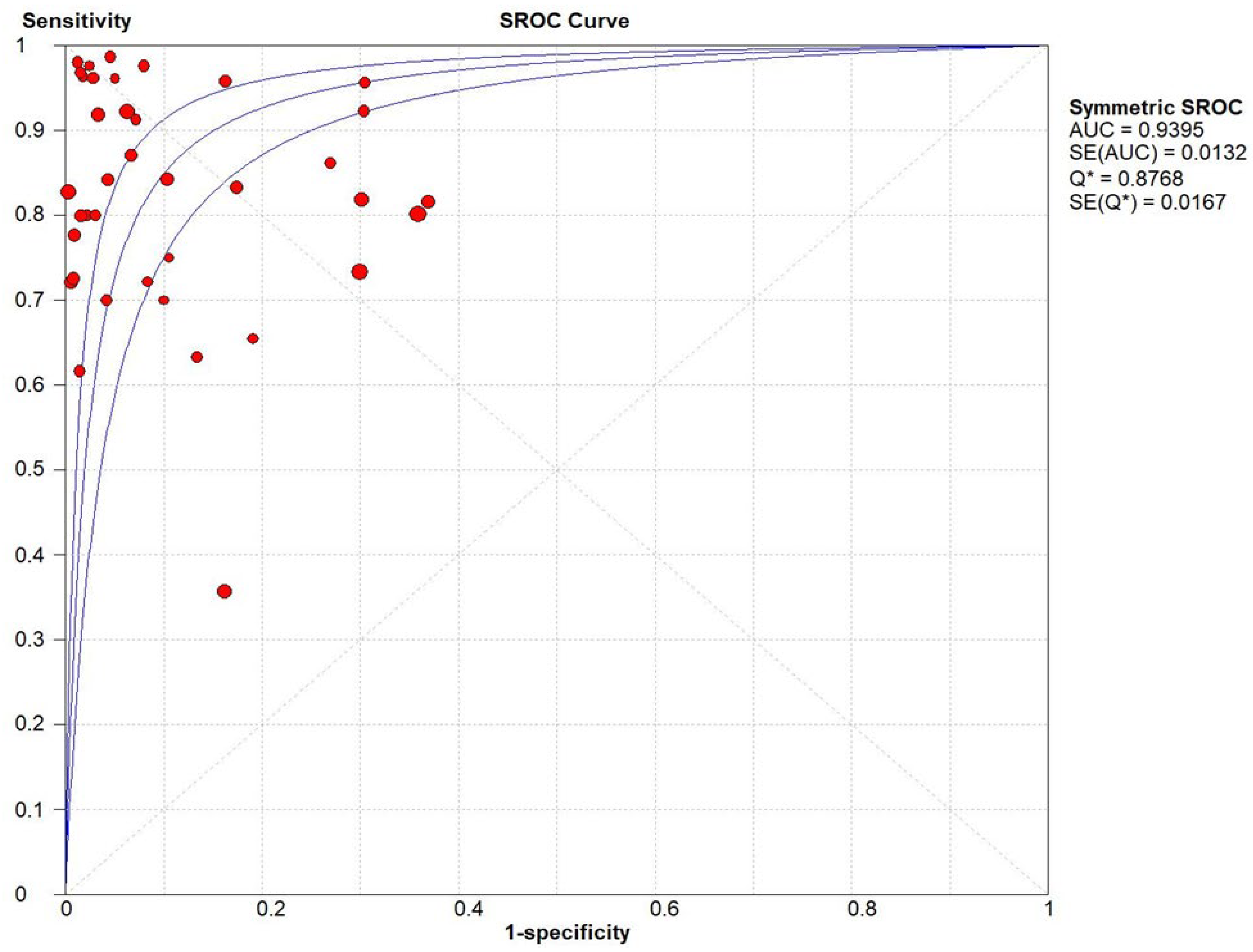

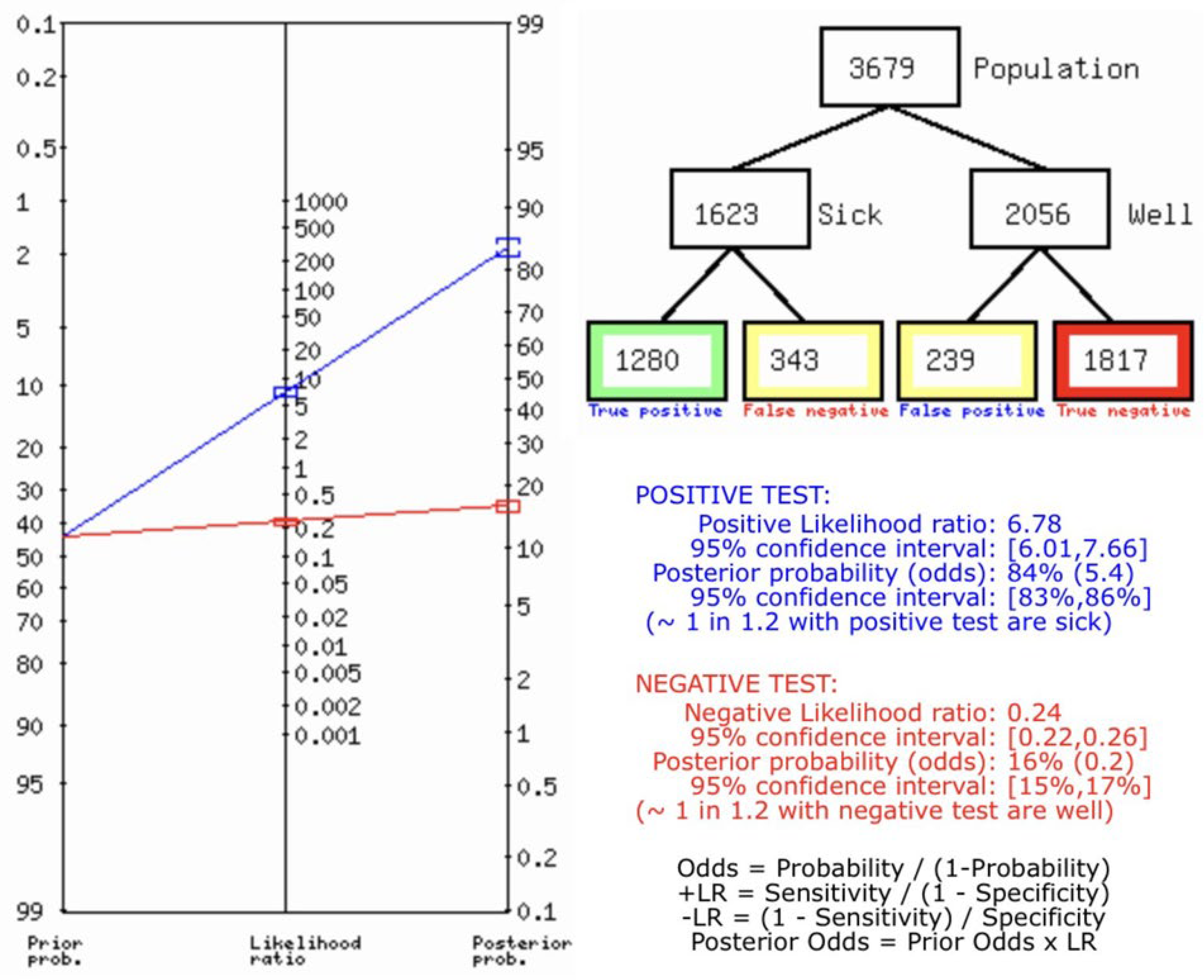

Statistical Analysis

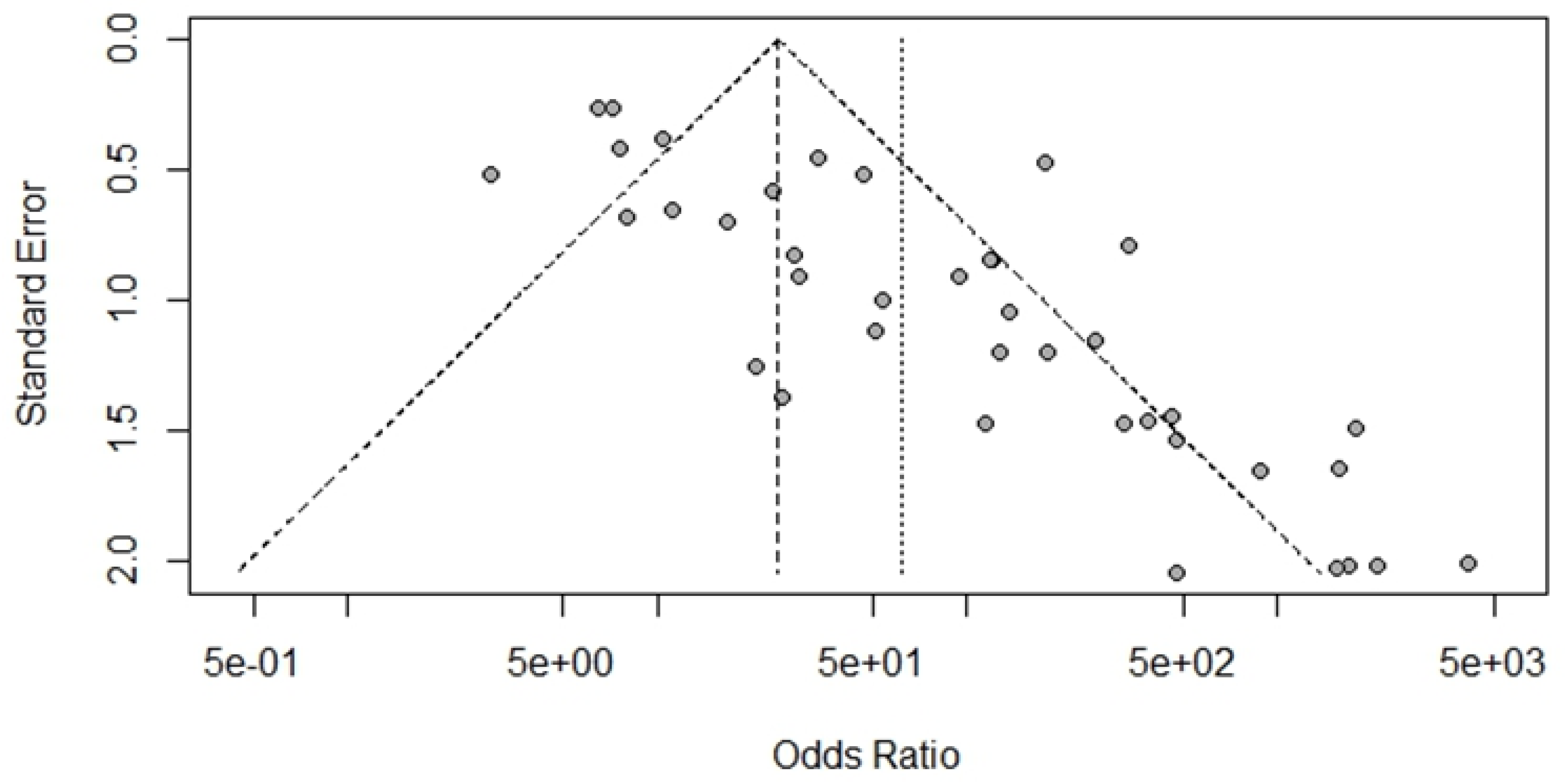

Bias Study

Result

Ultrasonography for Biliary Atresia vs Gold Standard

Discussion

Conclusion

Funding and Sponsorship

Ethical Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kotb MA, Kotb A, Sheba MF, El Koofy NM, El-Karaksy HM, Abdel-Kahlik MK, Abdalla A, El-Regal ME, Warda R, Mostafa H, Karjoo M, A-Kader HH. Evaluation of the triangular cord sign in the diagnosis of biliary atresia. Pediatrics. 2001 Aug;108(2):416-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg JK, Sun Y, Ju Z, Liu S, Jiang J, Koci M, Rosenberg J, Rubesova E, Barth RA. Ultrasound shear wave elastography: does it add value to gray-scale ultrasound imaging in differentiating biliary atresia from other causes of neonatal jaundice? Pediatr Radiol. 2021 Aug;51(9):1654-1666. Epub 2021 Mar 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou LY, Jiang H, Shan QY, Chen D, Lin XN, Liu BX, Xie XY. Liver stiffness measurements with supersonic shear wave elastography in the diagnosis of biliary atresia: a comparative study with grey-scale US. Eur Radiol. 2017 Aug;27(8):3474-3484. Epub 2017 Jan 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongsawasdi L, Ukarapol N, Visrutaratna P, Singhavejsakul J, Kattipattanapong V. Diagnostic evaluation of infantile cholestasis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008 Mar;91(3):345-9. [PubMed]

- Dong B, Weng Z, Lyu G, Yang X, Wang H. The diagnostic performance of ultrasound elastography for biliary atresia: A meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022 Oct 26;10:973125. PMCID: PMC9643747. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz S, Wild Y, Rosenthal P, Goldstein RB. Pseudo gallbladder sign in biliary atresia--an imaging pitfall. Pediatr Radiol. 2011 May;41(5):620-6; quiz 681-2. Epub 2011 Mar 16. PMCID: PMC3076559. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boo YA, Chang MH, Jeng YM, Peng SF, Hsu WM, Lin WH, Chen HL, Ni YH, Hsu HY, Wu JF. Diagnostic Performance of Transient Elastography in Biliary Atresia Among Infants With Cholestasis. Hepatol Commun. 2021 Feb 26;5(5):882-890. PMCID: PMC8122382. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillman JR, DiPaola FW, Smith SJ, Barth RA, Asai A, Lam S, Campbell KM, Bezerra JA, Tiao GM, Trout AT. Prospective Assessment of Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography for Discriminating Biliary Atresia from Other Causes of Neonatal Cholestasis. J Pediatr. 2019 Sep;212:60-65.e3. Epub 2019 Jun 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donia AE, Ibrahim SM, Kader MS, Saleh AM, El-Hakim MS, El-Shorbagy MS, Mansour MM, Gibriel MA. Predictive value of assessment of different modalities in the diagnosis of infantile cholestasis. J Int Med Res. 2010;38(6):2100-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan X, Peng Y, Liu W, Yang L, Zhang J. Does Supersonic Shear Wave Elastography Help Differentiate Biliary Atresia from Other Causes of Cholestatic Hepatitis in Infants Less than 90 Days Old? Compared with Grey-Scale US. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Jun 2;2019:9036362. PMCID: PMC6582890. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan X, Peng Y, Liu W, Yang L, Zhang J. Does Supersonic Shear Wave Elastography Help Differentiate Biliary Atresia from Other Causes of Cholestatic Hepatitis in Infants Less than 90 Days Old? Compared with Grey-Scale US. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Jun 2;2019:9036362. PMCID: PMC6582890. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Guindi MA, Sira MM, Sira AM, Salem TA, El-Abd OL, Konsowa HA, El-Azab DS, Allam AA. Design and validation of a diagnostic score for biliary atresia. J Hepatol. 2014 Jul;61(1):116-23. Epub 2014 Mar 18. Erratum in: J Hepatol. 2015 Jul;63(1):289. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrant P, Meire HB, Mieli-Vergani G. Improved diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary atresia by high-frequency ultrasound of the gall bladder. Br J Radiol. 2001 Oct;74(886):952-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanquinet S, Rougemont AL, Courvoisier D, Rubbia-Brandt L, McLin V, Tempia M, Anooshiravani M. Acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) elastography for the noninvasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2013 Mar;43(5):545-51. Epub 2012 Dec 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey TM, Stringer MD. Biliary atresia: US diagnosis. Radiology. 2007 Sep;244(3):845-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanieh MH, Dehghani SM, Bagheri MH, Emad V, Haghighat M, Zahmatkeshan M, Forutan HR, Rasekhi AR, Gheisari F. Triangular cord sign in detection of biliary atresia: is it a valuable sign? Dig Dis Sci. 2010 Jan;55(1):172-5. Epub 2009 Feb 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang LP, Chen YC, Ding L, Liu XL, Li KY, Huang DZ, Zhou AY, Zhang QP. The diagnostic value of high-frequency ultrasonography in biliary atresia. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013 Aug;12(4):415-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanegawa K, Akasaka Y, Kitamura E, Nishiyama S, Muraji T, Nishijima E, Satoh S, Tsugawa C. Sonographic diagnosis of biliary atresia in pediatric patients using the “triangular cord” sign versus gallbladder length and contraction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003 Nov;181(5):1387-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim WS, Cheon JE, Youn BJ, Yoo SY, Kim WY, Kim IO, Yeon KM, Seo JK, Park KW. The hepatic arterial diameter was measured with the US: adjunct for US diagnosis of biliary atresia. Radiology. 2007 Nov;245(2):549-55. Epub 2007 Sep 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim MJ, Park YN, Han SJ, Yoon CS, Yoo HS, Hwang EH, Chung KS. Biliary atresia in neonates and infants: triangular area of high signal intensity in the porta hepatis at T2-weighted MR cholangiography with US and histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 2000 May;215(2):395-401. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee CH, Wang PW, Lee TT, Tiao MM, Huang FC, Chuang JH, Shieh CS, Cheng YF. The significance of functioning gallbladder visualization on hepatobiliary scintigraphy in infants with persistent jaundice. J Nucl Med. 2000 Jul;41(7):1209-13. [PubMed]

- Lee HJ, Lee SM, Park WH, Choi SO. Objective criteria of triangular cord sign in biliary atresia on US scans. Radiology. 2003 Nov;229(2):395-400. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee MS, Kim MJ, Lee MJ, Yoon CS, Han SJ, Oh JT, Park YN. Biliary atresia: color Doppler US findings in neonates and infants. Radiology. 2009 Jul;252(1):282-9. Erratum in: Radiology. 2011 Dec;261(3):1003. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee SM, Cheon JE, Choi YH, Kim WS, Cho HH, Kim IO, You SK. Ultrasonographic Diagnosis of Biliary Atresia Based on a Decision-Making Tree Model. Korean J Radiol. 2015 Nov-Dec;16(6):1364-72. Epub 2015 Oct 26. Erratum in: Korean J Radiol. 2016 Jan-Feb;17(1):173. PMCID: PMC4644760. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu YF, Ni XW, Pan Y, Luo HX. Comparison of the diagnostic value of virtual touch tissue quantification and virtual touch tissue imaging quantification in infants with biliary atresia. Int J Clin Pract. 2021 Apr;75(4):e13860. Epub 2020 Dec 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong B, Weng Z, Lyu G, Yang X, Wang H. The diagnostic performance of ultrasound elastography for biliary atresia: A meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022 Oct 26;10:973125. PMCID: PMC9643747. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal V, Saxena AK, Sodhi KS, Thapa BR, Rao KL, Das A, Khandelwal N. Role of abdominal sonography in the preoperative diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary atresia in infants younger than 90 days. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Apr;196(4):W438-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park WH, Choi SO, Lee HJ, Kim SP, Zeon SK, Lee SL. A new diagnostic approach to biliary atresia with emphasis on the ultrasonographic triangular cord sign: comparison of ultrasonography, hepatobiliary scintigraphy, and liver needle biopsy in the evaluation of infantile cholestasis. J Pediatr Surg. 1997 Nov;32(11):1555-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzrokh, Mohsen & Sobhiyeh, Mohammad & Heibatollahi, Motahare. (2009). The Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive and Negative Predictive Values of Stool Color test, Triangular Cord Sign, and Hepatobiliary Scintigraphy in Diagnosis of Infantile Biliary Atresia. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 11.

- Ryeom HK, Choe BH, Kim JY, Kwon S, Ko CW, Kim HM, Lee SB, Kang DS. Biliary atresia: feasibility of mangafodipir trisodium-enhanced MR cholangiography for evaluation. Radiology. 2005 Apr;235(1):250-8. Epub 2005 Mar 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen Q, Tan SS, Wang Z, Cai S, Pang W, Peng C, Chen Y. Combination of gamma-glutamyl transferase and liver stiffness measurement for biliary atresia screening at different ages: a retrospective analysis of 282 infants. BMC Pediatr. 2020 Jun 4;20(1):276. PMCID: PMC7271542. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shima H, Igarashi G, Wakisaka M, Hamano S, Nagae H, Koyama M, Kitagawa H. Noninvasive acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) elastography for assessing the severity of fibrosis in the post-operative patients with biliary atresia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012 Sep;28(9):869-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun Y, Zheng S, Qian Q. Ultrasonographic evaluation in the differential diagnosis of biliary atresia and infantile hepatitis syndrome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011 Jul;27(7):675-9. Epub 2011 Jan 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takamizawa S, Zaima A, Muraji T, Kanegawa K, Akasaka Y, Satoh S, Nishijima E. Can biliary atresia be diagnosed by ultrasonography alone? J Pediatr Surg. 2007 Dec;42(12):2093-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan Kendrick AP, Phua KB, Ooi BC, Tan CE. Biliary atresia: making the diagnosis by the gallbladder ghost triad. Pediatr Radiol. 2003 May;33(5):311-5. Epub 2003 Mar 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visrutaratna P, Wongsawasdi L, Lerttumnongtum P, Singhavejsakul J, Kattipattanapong V, Ukarapol N. Triangular cord sign and ultrasound features of the gall bladder in infants with biliary atresia. Australas Radiol. 2003 Sep;47(3):252-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Qian L, Jia L, Bellah R, Wang N, Xin Y, Liu Q. Utility of Shear Wave Elastography for Differentiating Biliary Atresia From Infantile Hepatitis Syndrome. J Ultrasound Med. 2016 Jul;35(7):1475-9. Epub 2016 May 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu JF, Lee CS, Lin WH, Jeng YM, Chen HL, Ni YH, Hsu HY, Chang MH. Transient elastography is useful in diagnosing biliary atresia and predicting prognosis after hepatoportoenterostomy. Hepatology. 2018 Aug;68(2):616-624. Epub 2018 May 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou LY, Wang W, Shan QY, Liu BX, Zheng YL, Xu ZF, Xu M, Pan FS, Lu MD, Xie XY. Optimizing the US Diagnosis of Biliary Atresia with a Modified Triangular Cord Thickness and Gallbladder Classification. Radiology. 2015 Oct;277(1):181-91. Epub 2015 May 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Methodology | True Positive (Tp) | False positive (FP) | False Negative (FN) | True Negative (TN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aziz 2011 [6] | USG | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Boo et al. 20 21 [7] | USG | 12 | 1 | 3 | 45 |

| Dillman 2019 [8] | USG | 13 | 0 | 0 | 28 |

| donia 2010 [9] | USG | 19 | 4 | 10 | 17 |

| Duan 2019 [10] | USG | 37 | 0 | 14 | 87 |

| Duan et al. 2019 [11] | USG | 43 | 9 | 8 | 78 |

| El-Guindi et al. 2014 [12] | USG | 19 | 4 | 11 | 26 |

| farrant 2001 [13] | USG | 34 | 4 | 3 | 117 |

| Hanquinet 2015 [14] | USG | 7 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Humphrey and Stringer 2007 [15] | USG | 22 | 0 | 8 | 60 |

| Imanieh et al. 2010 [16] | USG | 7 | 2 | 3 | 46 |

| Jiang et al. 2013 [17] | USG | 21 | 2 | 2 | 26 |

| kanegawa 2003 [18] | USG | 25 | 7 | 4 | 19 |

| Kim et al. 2007 [19] | USG | 32 | 2 | 6 | 45 |

| Kim et al. 2000 [20] | USG | 12 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Kotb et al. 2001 [1] | USG | 25 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| Lee et al. 2000 [21] | USG | 40 | 38 | 9 | 65 |

| Lee et al. 2003 [22] | USG | 16 | 1 | 4 | 65 |

| Lee et al. 2009 [23] | USG | 18 | 0 | 11 | 35 |

| Lee et al. 2015 [24] | USG | 36 | 0 | 10 | 54 |

| Liu et al. 20 21 [25] | USG | 24 | 10 | 2 | 23 |

| Liu et al. 20 2 2 [26] | USG | 68 | 22 | 15 | 51 |

| mittal 2011 [27] | USG | 25 | 12 | 5 | 57 |

| Park et al.1997 [28] | USG | 20 | 3 | 0 | 40 |

| Rouzrokh et al. 2009 [29] | USG | 13 | 2 | 5 | 22 |

| Ryeom et al. 2005 [30] | USG | 3 | 2 | 1 | 17 |

| Sandberg 2021 [2] | USG | 170 | 38 | 42 | 68 |

| Shen et al. 2020 [31] | USG | 99 | 44 | 36 | 103 |

| Shima 2012 [32] | USG | 7 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| sun 2011 [33] | USG | 54 | 5 | 97 | 26 |

| Takamizawa et al. 2007 [34] | USG | 46 | 6 | 2 | 31 |

| Tan Kendrick et al. 2003 [35] | USG | 26 | 0 | 5 | 186 |

| visrutaratna 2003 [36] | USG | 22 | 7 | 1 | 16 |

| Wang et al. 2016 [37] | USG | 37 | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| Wang 2016 [37] | USG | 37 | 1 | 0 | 31 |

| Wongsawasdi et al. 2008 [4] | USG | 27 | 2 | 4 | 28 |

| Wu et al. 2018 [5] | USG | 12 | 1 | 3 | 32 |

| Wu 2018 [38] | USG | 15 | 0 | 0 | 33 |

| Zhou et al. 2015 [39] | USG | 119 | 9 | 10 | 135 |

| Zhou 2017 [3] | USG | 109 | 12 | 11 | 40 |

| Author and Year | Patient Selection | Index Test | Reference Standard | Flow and Timing | Patient Selection | Index Test | Reference Standard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aziz 2011 | low | low | unclear | low | low | low | low | |

| Boo et al. 20 21 | unclear | high | low | low | low | low | low | |

| Dillman 2019 | low | low | high | low | high | low | low | |

| donia 2010 | low | low | low | low | unclear | low | unclear | |

| Duan 2019 | low | high | high | unclear | low | unclear | low | |

| Duan et al. 2019 | low | unclear | low | low | low | low | low | |

| El-Guindi et al. 2014 | unclear | low | unclear | low | high | low | low | |

| farrant 2001 | low | low | high | low | low | low | low | |

| Hanquinet 2015 | low | low | unclear | low | low | unclear | low | |

| Humphrey and Stringer 2007 | low | unclear | low | unclear | low | low | low | |

| Imanieh et al. 2010 | low | low | high | low | low | low | low | |

| Jiang et al. 2013 | low | low | low | low | low | low | high | |

| kanegawa 2003 | low | high | low | low | low | high | low | |

| Kim et al. 2007 | low | high | low | unclear | low | low | low | |

| Kim et al. 2000 | unclear | low | low | low | high | low | high | |

| Kotb et al. 2001 | low | unclear | low | low | low | low | low | |

| Lee et al. 2000 | high | low | low | low | high | low | low | |

| Lee et al. 2003 | low | unclear | low | high | low | high | low | |

| Lee et al. 2009 | low | low | low | low | unclear | low | unclear | |

| Lee et al. 2015 | low | high | low | low | low | low | low | |

| Liu et al. 20 21 | low | low | unclear | low | low | high | low | |

| Liu et al. 20 2 2 | high | low | low | low | low | low | low | |

| mittal 2011 | low | unclear | low | high | low | low | unclear | |

| Park et al.1997 | low | low | unclear | low | high | low | low | |

| Rouzrokh et al. 2009 | low | low | high | low | low | low | low | |

| Ryeom et al. 2005 | low | low | low | low | low | low | low | |

| Sandberg 20 21 | unclear | high | low | low | low | unclear | low | |

| Shen et al. 20 20 | low | unclear | low | low | low | low | low | |

| Shima 201 2 | low | low | low | low | low | low | low | |

| sun 2011 | low | low | low | unclear | low | low | low | |

| Takamizawa et al. 2007 | low | low | unclear | low | low | high | low | |

| Tan Kendrick et al. 2003 | unclear | low | low | low | low | low | low | |

| visrutaratna 2003 | low | low | low | low | low | low | unclear | |

| Wang et al. 2016 | low | low | low | low | low | low | low | |

| Wang 2016 | low | high | low | high | low | low | unclear | |

| Wongsawasdi et al. 2008 | low | low | low | low | low | low | low | |

| Wu et al. 2018 | low | low | low | low | low | low | low | |

| Wu 2018 | low | low | high | low | low | low | low | |

| Zhou et al. 2015 | low | low | low | low | low | low | high | |

| Zhou 2017 | low | low | low | low | unclear | low | unclear |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).