Submitted:

24 April 2024

Posted:

26 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Diagnosis

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion

- −

- Studies that relate parenting style to the well-being, satisfaction and/or quality of life of families with children with ASD.

- −

- Published in the last 10 years including the diagnostic change from DSM IV to DSM 5 (2013) [22].

- −

- Written in Spanish or English.

- −

- Empirical articles (qualitative and/or quantitative).

2.3.2. Exclusion

- −

- Articles that referred to disability but did not specify ASD.

- −

- Those that did not include all three variables (family well-being, parenting style, and ASD).

- −

- Those that considered child satisfaction or marital satisfaction; and those that included only satisfaction with social or medical services were eliminated.

2.4. Identification and Selection of Studies

2.5. Bias Assessment

3. Results

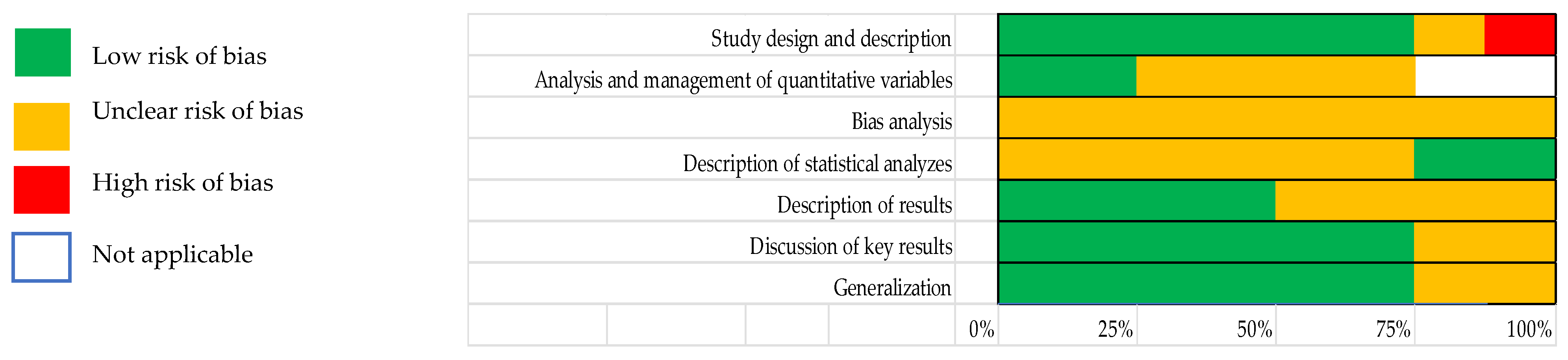

3.1. Elegibility

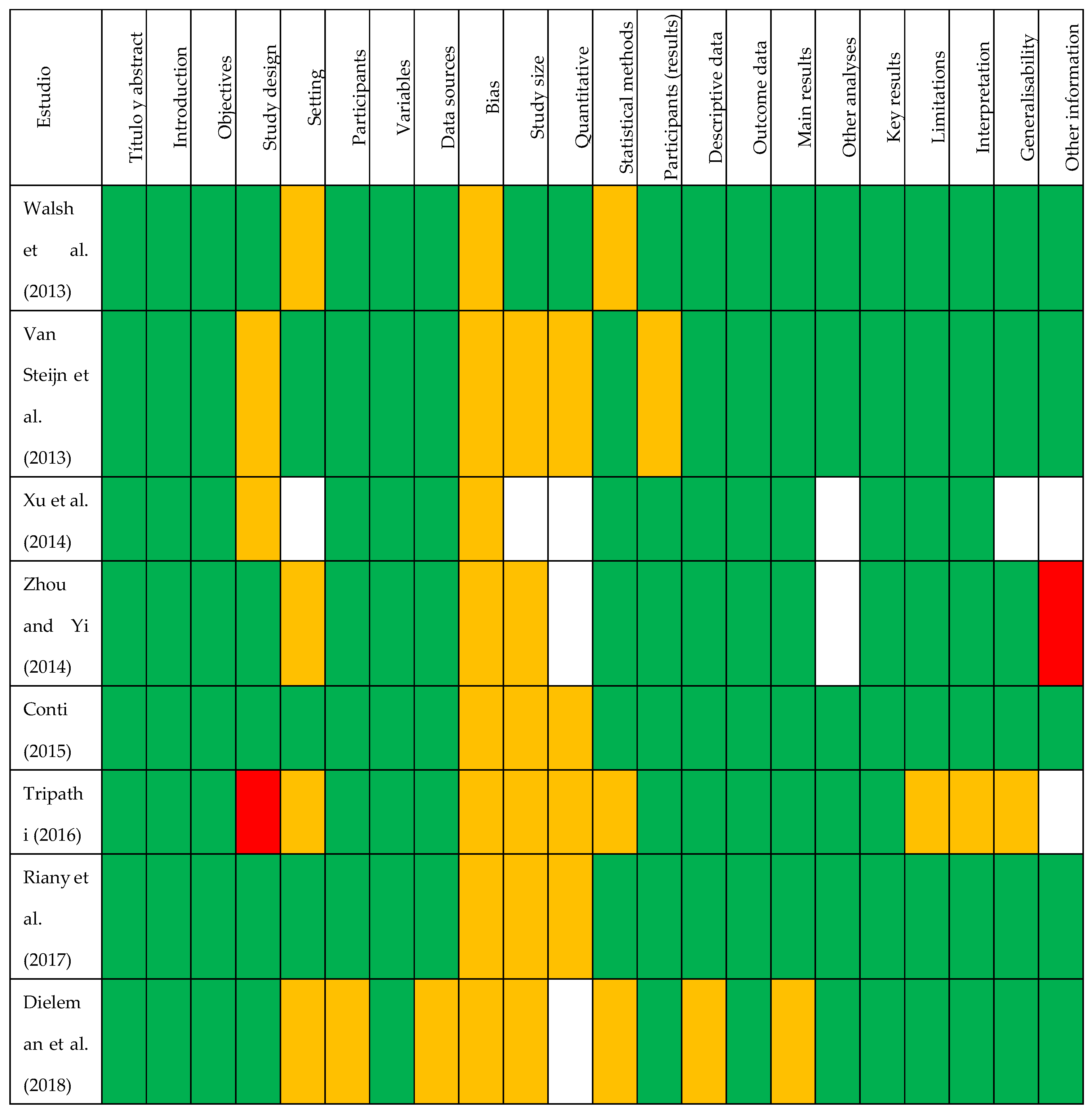

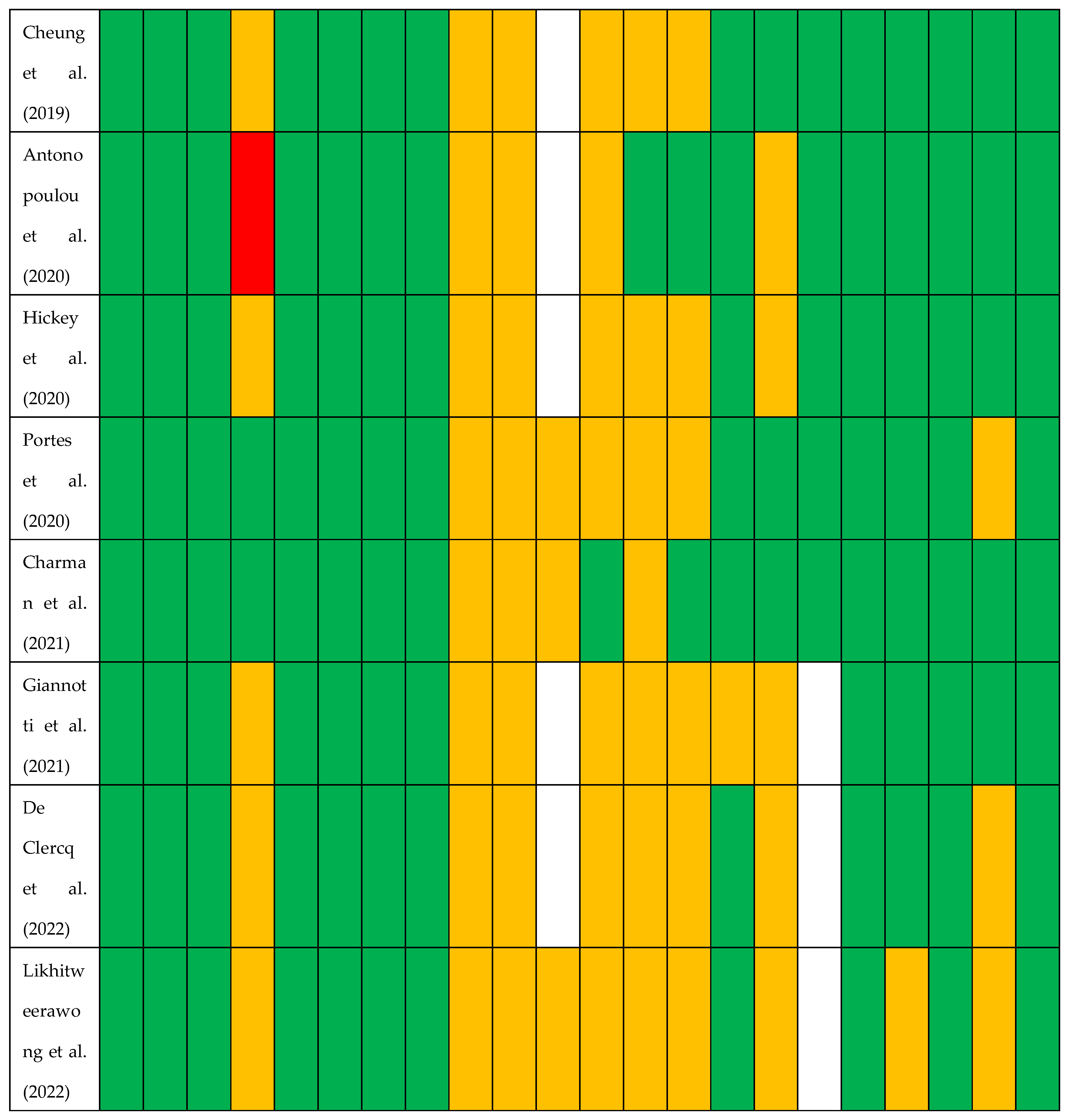

3.2. Methodological Strengths and Weaknesses

3.3. Summary of Extracted Data

3.4. Relationships between Study Variables

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix 2

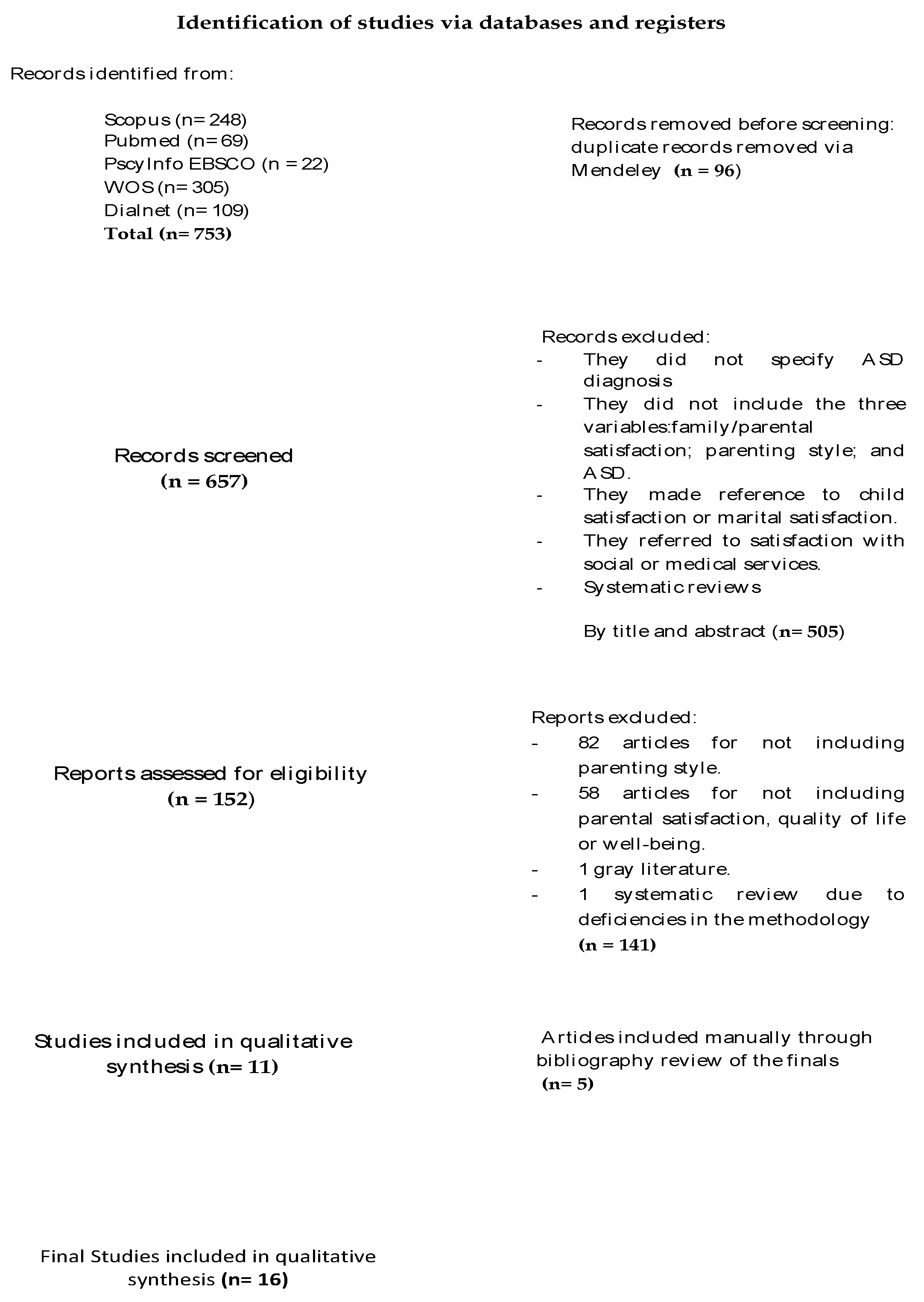

| Author | Participants | Purpose | Results |

| Walsh et al. (2013) | 148 mothers of autistic children (2-18 years old) | To evaluate pain and problematic behavior of autistic children as a predictor of parenting behavior, and parenting style and stress interaction with pain and behavior. | Greater pain in children increases problematic behavior and It implies more stress in parents and a more overprotective style. If pain is combined with overprotective style, parental stress is higher. |

| Van Steijn et al. (2013) | 6 fathers and 96 mothers with possible ASD and/or ADHD. 96 children with ASD + ADHD (2-20 years), siblings not diagnosed with a disability. |

To measure the effect of the diagnosis of ASD or ASD+ADHD on undiagnosed children in parenting styles. | More permissive parents with children with ASD. ADHD in fathers and ASD in mothers leads to more permissiveness with non-autistic children. |

| Xu et al. (2014) | 33 parents. 24 boys and 9 girls ASD (2.5-5 years old). | To examine the correlation between parental depression and child behavior problems and parenting style mediation in families with children with ASD. | Authoritative style correlated with more behavioral problems and depression than authoritarian and permissive style. Authoritarian and permissive styles alternate, but they do not correlate with behavioral problems in children or depression in parents. |

| Zhou and Yi (2014) | 32 fathers and mothers. 27 boys and 1 girl ASD (6.75 mean years) | Understand parenting styles of parents with ASD children and discuss parenting experiences on how to manage symptoms. |

Relationship-based style are warmer, less stressed, more emotionally regulated, and more tolerant of the symptoms of children with ASD, as opposed to training-based style, alternation, or self-isolation. |

| Conti (2015) | 74 mothers of autistic children and 46 mothers of non-autistic children (5-18 years) | Role of compassionate parenting goals and self-image in the experience of mothers of children with ASD. |

Compassionate parenting is more beneficial than self-image-based parenting. Mothers of autistic children showed greater compassionate parenting but lower life satisfaction than mothers of non-autistic children. |

| Tripathi (2016) | 320 parents and 320 children with ASD (5-22 years old). | Analyze parenting style of parents with different levels of stress and children with ASD |

Mothers are more permissive than fathers. Mothers and fathers are more authoritarian the greater the severity of symptoms. More permissive style in pre-adolescence and higher stress in adolescence. |

| Riany et al. (2017) |

388 mothers, 71 fathers and 247 sons and 212 daughters non-autistic children.86 mothers, 14 fathers and 71 mother of autistic sons and 30 autistic daughters (3-10 years). |

To compare parenting styles, parent-child relationships, and social support in parents of autistic and non-autistic children. |

Parents of autistic children are more authoritarian, less warm, less relational parenting, and more assertive power in front of a group of non-autistic children. Parents of autistic children have less social support than the group non-autistic children. |

| Dieleman et al. (2018) | 15 mothers, 5 fathers, 11 boys and 7 girls with ASD (6-17 years). | Interaction between parenting styles and experiences of parents and how ASD affects the child. | Mutual influence: parenting style (based on autonomy, structure and support in relationships) and feedback from children. The style depends on the needs of the parents. |

| Cheung et al. (2019) | 111 mothers, 25 fathers and 111 sons and 25 daughters with ASD (mean 9.39 years). | Role of stress in parental characteristics (disposition to conscious parenting, stigma and mental well-being) and behavioral adjustment of children with ASD. |

Less stress promotes mindful parenting, higher quality relationships, greater well-being, fewer behavioral difficulties, and more prosocial behaviors in children with ASD. |

| Antonopoulou et al. (2020) | 34 mothers and 16 fathers with ASD; 40 mothers and 10 fathers without ASD (4-12 years). | Correlation between anxiety, expression of emotions, coping strategies, and parenting styles of parents of children with and without ASD. | Parents with ASD had greater negative emotional expression, higher levels of anxiety, permissive style and less authoritative than parents of children without ASD Positive emotional expression predicts coping strategies and supportive parenting styles in both groups of parents. |

| Hickey et al. (2020) | 166 stable couples with children with ASD (5-12 years). | To assess whether parental stress and depressive symptoms in parents predict the emotional quality of the relationship between parents and children with ASD |

Mothers had more stress and depression than fathers, who predicted more criticism.Greater stress in mothers influences the father's self-perception of warmth. Increased stress in parents is related to criticism. |

| Portes et al. (2020) | 45 fathers and 45 mothers, 39 sons and 44 daughters with ASD (3-7 years). | Correlation between behavior of children with ASD, parenting styles and co-parenting, as a function of the behavior of children with ASD. |

Parents of children with behavioral problems present more authoritarian/permissive parenting and negative impacts on co-parenting. Parents of more prosocial children have more authoritative parenting and better quality of co-parenting. Couples who do not recognize good practices in their partners, more relationship and behavior problems in children. |

| Charman et al. (2021) |

57 mothers, 3 fathers and 2 grandmothers with children with ASD (4 -8.11 years). |

Feasibility and efficacy of parental behavioral intervention for emotional and behavioral problems in children with ASD. |

Lax and hyperreactive practices are associated with increased stress and lower parental well-being. |

| Giannotti et al. (2021) | Group Italy: 47 mothers, 45 fathers, 40 boys and 7 girls ASD.Japan Group: 47 mothers, 42 fathers, 38 boys and 9 girls with ASD (mean 8.9 years). | Differences in parental stress and parenting style between Italian and Japanese mothers and fathers of children with ASD; and the predictive role of culture, sociodemographics, and child characteristics on parental stress and predictors of parenting style. | Japanese fathers (not mothers) have more stress and less commitment in parenting style than Italians. In both cultures: mothers have more social interaction with their children than fathers, and more severe ASD and more stress in parents.Japanese culture, male gender, and stress are related to dysfunctional interaction and predict parenting style. |

| De Clercq et al. (2022) | 447 parents: 67 children with Cerebral Palsy (CP) (mean 12.4 years), 54 children with Down syndrome (DS) (mean 13.12 years), 159 children with ASD (mean 10.8 years) and 167 children without disabilities (mean 13.3 years). | To examine the family's emotional climate and relationship with stress and parental behaviors in ASD, CP, SD and without disabilities. | Parents without disabilities, less Emotion Expressed. Parents of children with disabilities, more responsive parenting. Parents with ASD have more Expressed Emotion, more stress, and hyper-reactive parenting than DS and CP (more critical and less warmth). With and without disabilities, parental warmth is related to children's well-being. |

| Likhitweerawong et al. (2022) | 61 caregivers of children with ASD and 63 without ASD. 49 boys and 12 girls with ASD, 43 boys and 20 girls without ASD (6-12 years). |

To assess parenting style, stress, and quality of life of caregivers of children with and without ASD. | ASD caregivers: more stress, depression, anxiety, and lower quality of life; parenting style that is more permissive and authoritarian, and less authoritative than without ASD. Negative correlation between quality of life of children with ASD and authoritarian and permissive parenting styles. More stress with school-age ASD children. |

References

- Alcantud Marín, F., Alonso Esteban, Y., & Mata Iturralde, S. Prevalencia de los trastornos del espectro autista: revisión de datos. Siglo Cero 2016, 47(4), 7–26. [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R. R. Parenting Stress Index, 3ª ed.; Professional Manual: Odesa, Psychological Assessment Resources, FL, USA, 1995.

- Dabrowska, A., & Pisula, E. Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2010, 54(3), 266–280. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S., & Watson, S. The impact of parenting stress: a meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2013, 43(3), 629-642. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., Yen, H., Tseng, M., Tung, L., & Chen, Y. Impacts of autistic behaviors, emotional and behavioral problems on parenting stress in caregivers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2014, (44), 1383-1390. [CrossRef]

- Hickey, E., Hartley, S., & Papp, L. Psychological well-being and parent-child relationship quality in relation to child autism: An actor-partner modeling approach. Family Process 2020, 59(2), 636-650. [CrossRef]

- Gavín-Chocano Ó, García-Martínez I, Torres-Luque V, Checa-Domene L. Resilient Moderating Effect between Stress and Life Satisfaction of Mothers and Fathers with Children with Developmental Disorders Who Present Temporary or Permanent Needs. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2024, 14(3):474-487. [CrossRef]

- Karst, J.S.; Van Hecke, A. Parent and family impact of autism spectrum disorders: a review and proposed model for intervention evaluation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. [CrossRef]

- Hock, R. M., Timm, T., & Ramisch, J. Parenting children with autism spectrum disorders: a crucible for couple relationships. Child & Family Social Work 2012, 17(4), 406-415. [CrossRef]

- Gau, S.S., Chou, M., Chiang, H., Lee, J., Wong, C., Chou, W., & Wu, Y. Parental adjustment, marital relationship, and family function in families of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 2012, 6(1), 263-270. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Marí I, Tárraga-Mínguez R, Pastor-Cerezuela G. Analysis of Spanish Parents’ Knowledge about ASD and Their Attitudes towards Inclusive Education. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2022, 12(7):870-881. [CrossRef]

- Arellano, A., Denne, L., Hastings, R., & Hug, J. Parenting sense of competence in mothers of children with autism: Associations with parental expectations and levels of family support needs. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 2019, 44(2), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- May, C., Fletcher, R., Dempsey, I., & Newman, L. Modeling relations among coparenting quality, autism-specific parenting self-efficacy, and parenting stress in mothers and fathers of children with ASD. Parenting 2015, 15(2), 119-133. [CrossRef]

- Ventola, P., Lei, J., Paisley, C., Lebowitz, E., & Silverman, W. Parenting a child with ASD: comparison of parenting style between ASD, anxiety, and typical development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2017, (47), 2873-2884. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T., & Yi, C. Parenting styles and parents’ perspectives on how their own emotions affect the functioning of children with autism spectrum disorders. Family Process 2014, 53(1), 67-79. [CrossRef]

- Shirley, M. The first two years. Personality manifestations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, USA, 1993.

- Sameroff, A. The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Verny, T., & Kelly, J. La vida secreta del niño antes de nacer. Barcelona: Urano, 1988.

- Silver, W., & Rapin, I. Neurobiological basis of autism. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012, 59(1), 45-61. [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. The discipline controversy revisited. Family Relations 1996, 45(4), 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyches, T., Smith, T., Korth, B., Roper, S., & Mandleco, B. Positive parenting of children with developmental disabilities: A meta-analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2012, 33(6), 2213-2220. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th. Arlington, EEUU: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Page, M., Moher, D., Bossuyt , P., Boutron , I., Hoffmann , T., & Mulrow , C. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. Submitted, BMJ 2021;372:n160. [CrossRef]

- Likhitweerawong , N., Boonchooduang , N., & Louthrenoo, O. Parenting Styles, Parental Stress, and Quality of Life Among Caregivers of Thai Children with Autism. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dieleman , L., Moyson , T., De Pauw , S., Prinzie , P., & Soenens , B. Parents' Need-related Experiences and Behaviors When Raising a Child With Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Pediatr Nurs 2018, (42), e26-e37. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C., Mulder, E., & Tudor, M. Predictors of parent stress in a sample of children with ASD: Pain, problem behavior, and parental coping. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 2013, 7(2), 256-264. [CrossRef]

- Charman, T., Palmer, M., Stringer, D., Hallett, V., Mueller, J., Romeo, R., & Simonoff, E. A novel group parenting intervention for emotional and behavioral difficulties in young autistic children: Autism spectrum treatment and resilience (ASTAR): A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2021, 60(11), 1404-1418. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N. Parenting Style and Parents’ Level of Stress having Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (CWASD): A Study based on Northern India. Neuropsychiatry 2016, 5(1), 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González de Dios , J., Buñuel Álvarez , J., & González Rodríguez , P. Listas guía de comprobación de estudios observacionales: declaración STROBE . Evidencias en pediatría 2012, 8(3), 65.

- Antonopoulou, K., Manta, N., Maridaki-Kassotaki, K., Kouvava, S., & Stampoltzis, A. Parenting and coping strategies among parents of children with and without autism: the role of anxiety and emotional expressiveness in the family. Austin Journal of Autism & Related Disabilities 2020, 6(1), 1054.

- Cheung, R., Leung, S., & Mak, W. (2019). Role of Mindful Parenting, Affiliate Stigma, and Parents’ Well-being in the Behavioral Adjustment of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Testing Parenting Stress as a Mediator. Mindfulness 2019, (10), 2352–2362. [CrossRef]

- Riany , Y., Cuskelly , M., & Meredith, P. Parenting Style and Parent–Child Relationship: A Comparative Study of Indonesian Parents of Children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). J Child Fam Stud 2017, (26), 3559–3571. [CrossRef]

- Van Steijn, D., Oerlemans, A., Ruiter, S., van Aken, M., Buitelaar, J., & Rommelse, N. Are parental autism spectrum disorder and/or attention-deficit/Hyperactivity disorder symptoms related to parenting styles in families with ASD (+ADHD) affected children? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2013, 22(11), 671–681. [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, L., Prinzie, P., Warreyn, P., Soenen, B., Dieleman, L., & De Pauw, S. Expressed emotion in families of children with and without autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy and down syndrome: relations with parenting stress and parenting behaviors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2022, 52(4), 1789-1806. [CrossRef]

- Giannotti, M., Bonatti, S., Tanaka, S., Kojima, H., & De Falco, S. Parenting Stress and Social Style in Mothers and Fathers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Cross- Cultural Investigation in Italy and Japan. Brain Sciences 2021, (11), 1419. [CrossRef]

- Portes, J.M.R., Vieira, M.L., Souza, C.D., & Kaszubowski, E. Parental styles and coparenting in families with children with autism: cluster analysis of children’s behavior. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas) 2020, 37. [CrossRef]

- Conti, R. Compassionate Parenting as a Key to Satisfaction, Efficacy and Meaning Among Mothers of Children with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Cameron , L., & Parker, N. Parental Depression and Child Behavior Problems: A Pilot Study Examining Pathways of Influence. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2014, 7(2), 126–142. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Prentice Hall: Englewood cliffs, NJ, 1977.

- Ilias, K., Cornish, K., Kummar, A. S., Park, M. S. A., & Golden, K. J. Parenting stress and resilience in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in Southeast Asia: A systematic review. Frontiers in psychology 2018, 9, 288865. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo López, M., Máiquez Chaves, M., MartÍn Quintana, J., & RodrÍguez Ruiz, B. Manual práctico de parentalidad positiva. Madrid: Síntesis, 2015.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).