Submitted:

24 April 2024

Posted:

26 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Issues and a New Framework

2.1. The Traditional Objective Framework

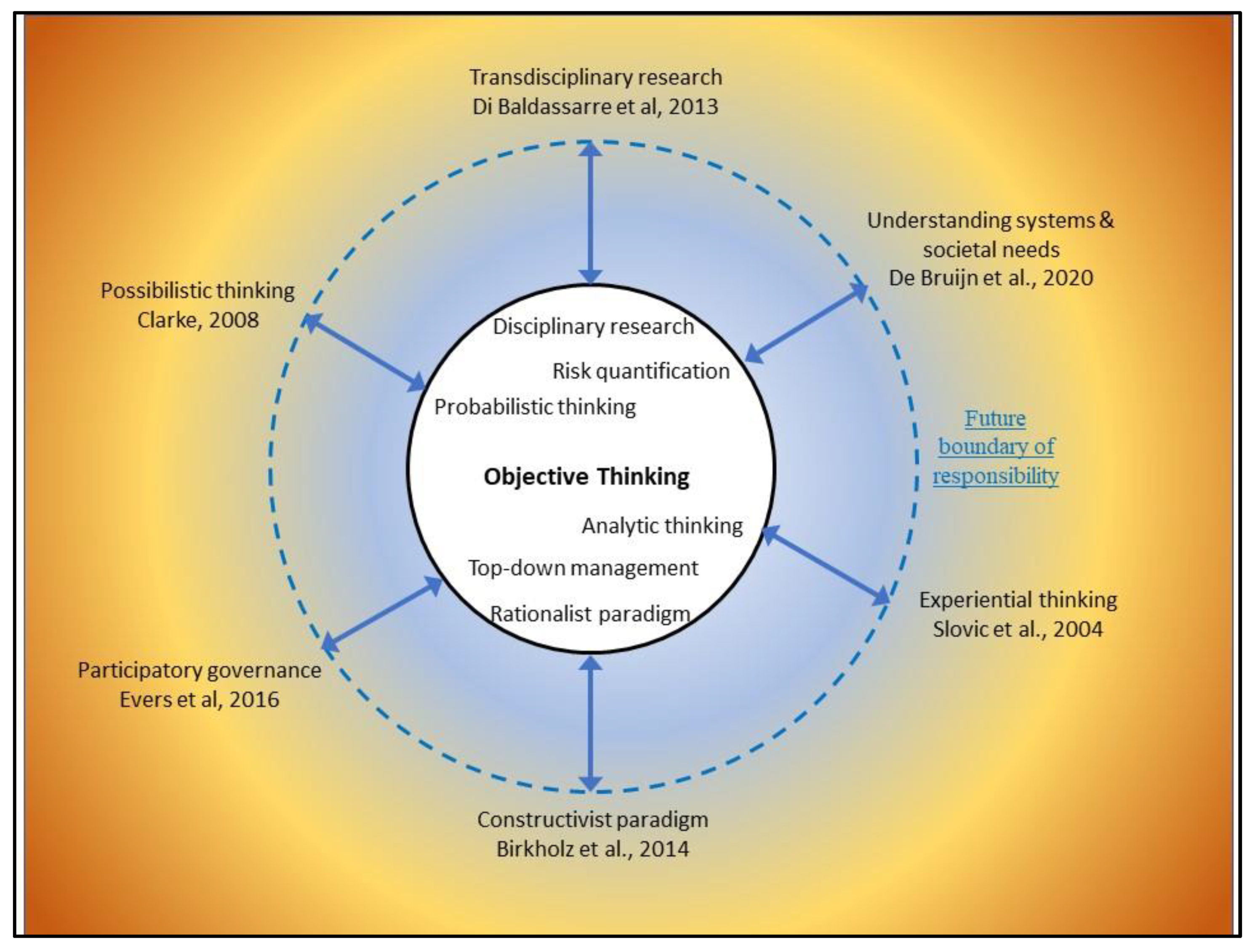

2.2. A Framework for Critical Complexity

- Applying transdisciplinary thinking [41,42,43] to guide flood scholarship. Conventional disciplines become barriers to investigating multi-level interactions and the study of sustainability in a multi-level world [44]. Transdisciplinarity opens up possibilities for societal understanding of hazards and options for mitigation that are currently obscured by disciplinary perspectives [35].

- Utilizing constructivist approaches that see “risk as socially constructed and shaped and constrained by social environments” [23] to help people move beyond the rationalist paradigm that hazard protection has to be based entirely on decisions made by experts.

3. Bringing the Conceptual Frameworks to Practice

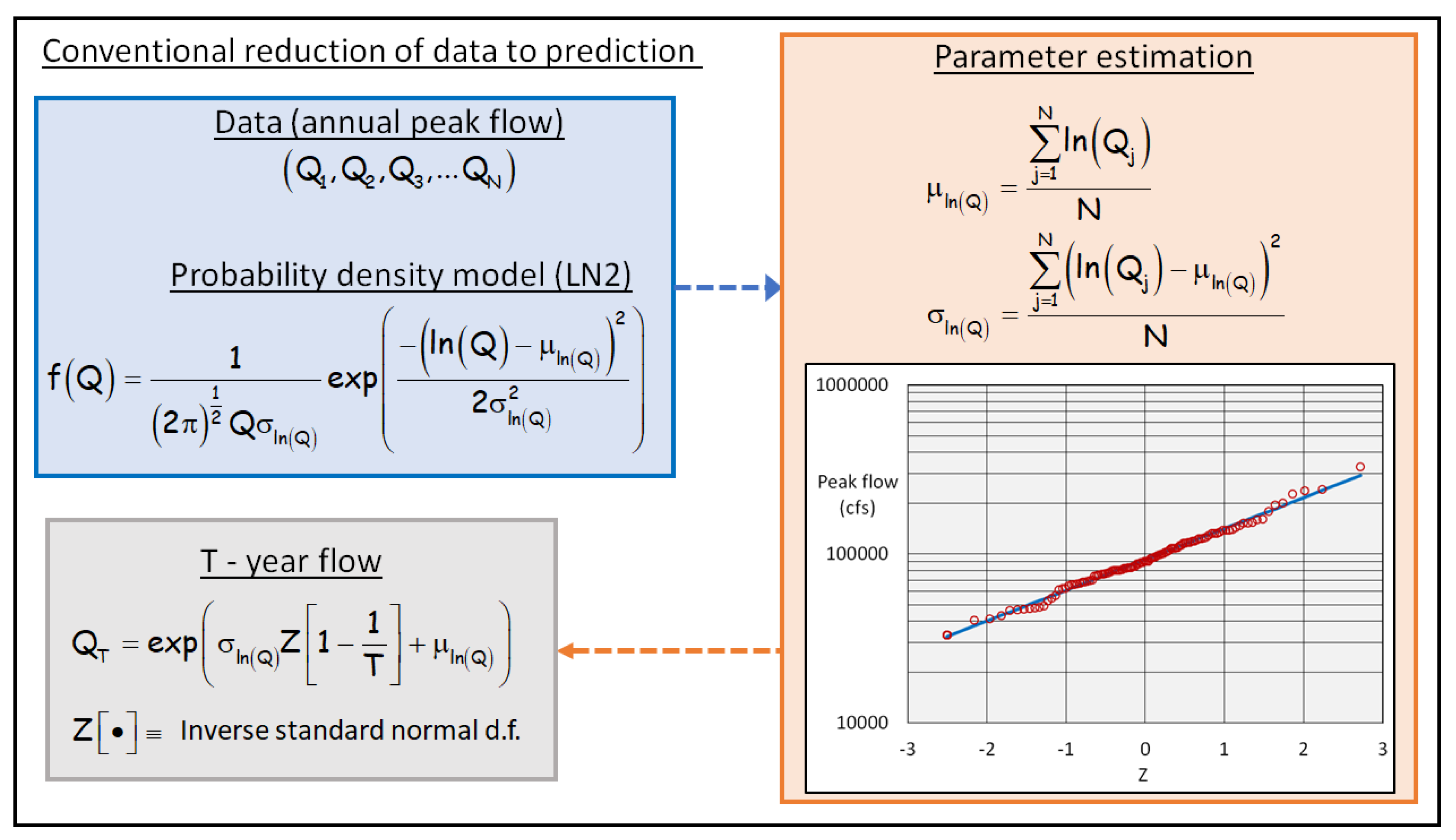

3.1. Traditional Analytic and Probabilistic Framework in Practice

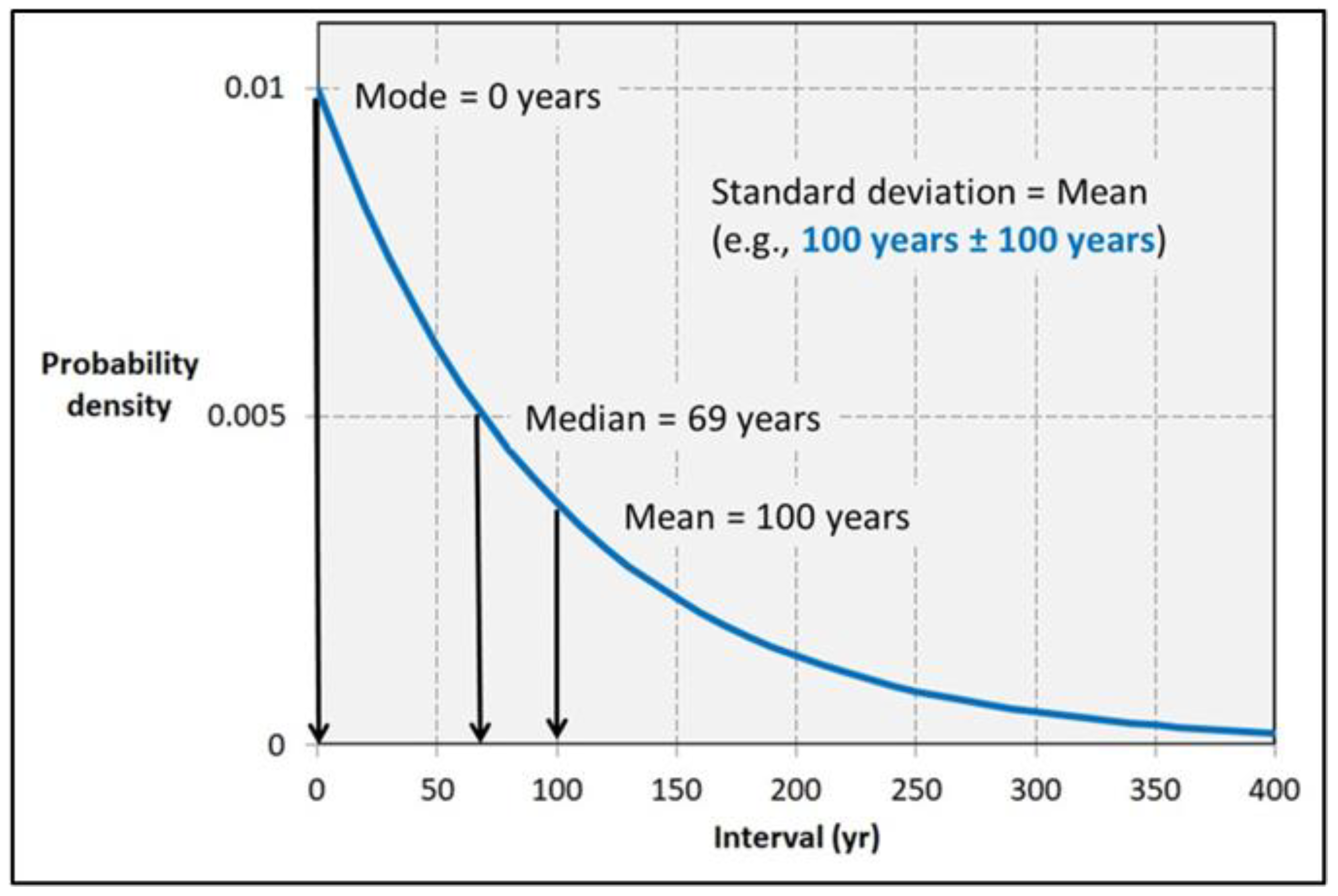

- Recurrent events experienced in everyday life often occur at nearly fixed intervals, such as weekly, monthly, or annual meetings. We are conditioned to expect a small degree of irregularity (e.g., a monthly meeting might not recur on exactly the same day of the month). But experts model recurring hazards, such as floods, as random events. The public’s preconception does not match the probability distribution of recurrence intervals. For example, the distribution of intervals between “100-year floods” is broad, strongly skewed, and reaches its mode at zero (Figure 3). The standard deviation of recurrence intervals is equal to their average, so that Q100 could be stated as the “flow that is exceeded every 100 years ± 100 years, on average” (Figure 3). Because most people do not understand the technical nuances there is a strong tendency for them to revert to an incorrect understanding of Q100 as “a flood that happens every 100 years.”

- The public typically associates probability with the chance of a single outcome. For example, the probability of a coin landing heads (p = 0.5), of rolling a particular point on a die (p = 0.167), or of winning top prize in a high-profile lottery game (p < 0.000001). In contrast, flood risk accumulates over time: Q100 has a probability of 0.01 each year: the longer the exposure to risk, the greater the chance of experiencing a 100-year flood. Most of the public lacks meaningful experience with this type of accumulative risk and incorrectly simplifies the risk of a 100-year flood to “p = 0.01” (not 0.01/year).

- The public perceives flooding as a singular event associated with a particular flow, elevation of water, or inundation of land. Past floods are remembered by particular flood marks recorded on buildings or other structures. This view is reinforced by the “thin grey lines” on flood insurance rate maps (FIRM) that demarcate flood plains [51]. In contrast, a 100-year flood is not a single flow but any flow that exceeds Q100, with no upper limit. Without ways to understand the possibilities of flows that might greatly exceed Q100, people tend to think of the 100-year flood as exactly the flow of Q100, which is the smallest 100-year flood.

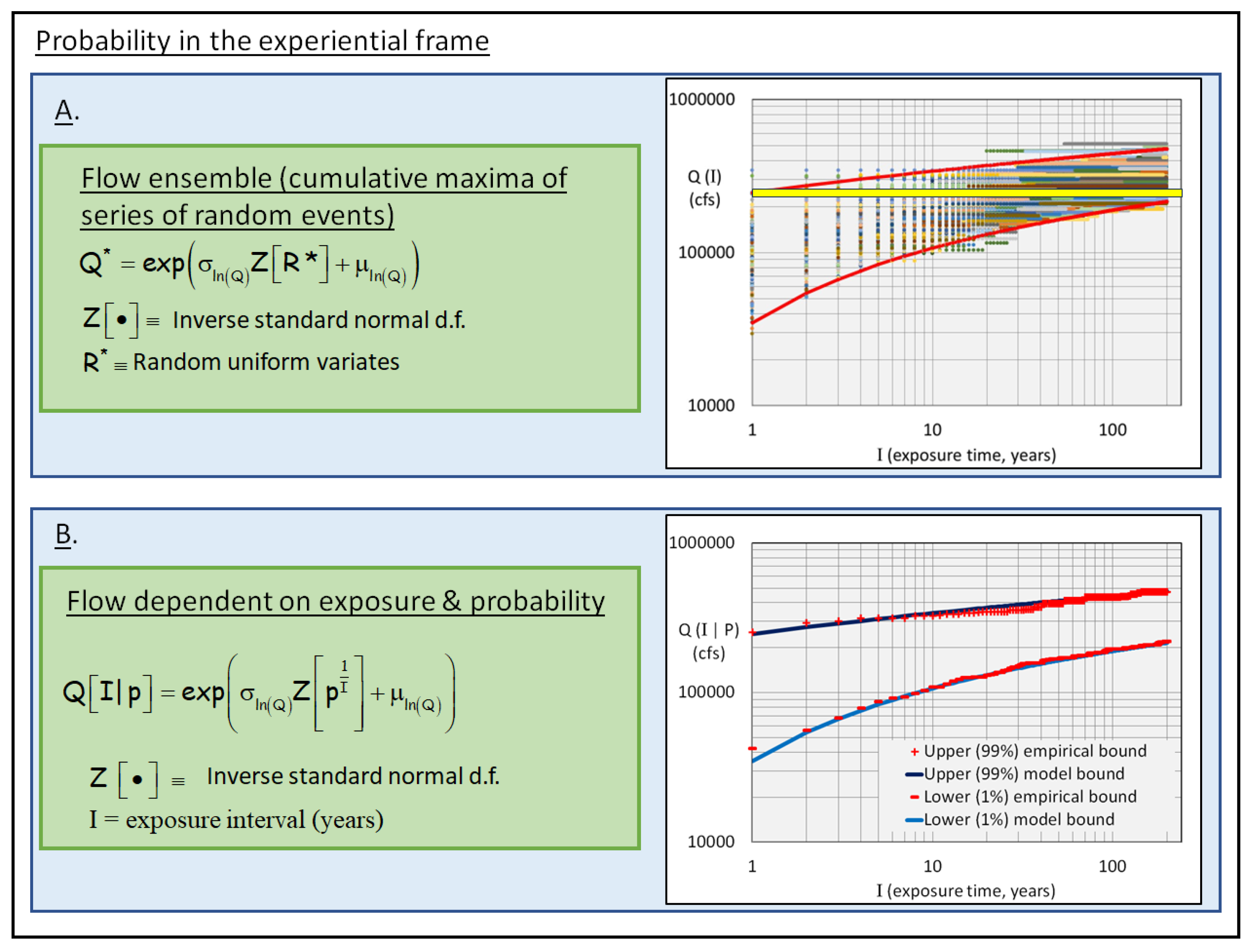

3.2. Connecting Subjective Understanding with Objective Measures of Flood Risk

- Q(I) ensembles intrinsically incorporate the passage of time through successive simulations of annual peak flows. Like a game, Q(I) simulates the experience of exposure to a flood hazard. In contrast, an average recurrence interval (e.g., “100-year” flood) is a statistical parameter, not a time that can be related to experience [30].

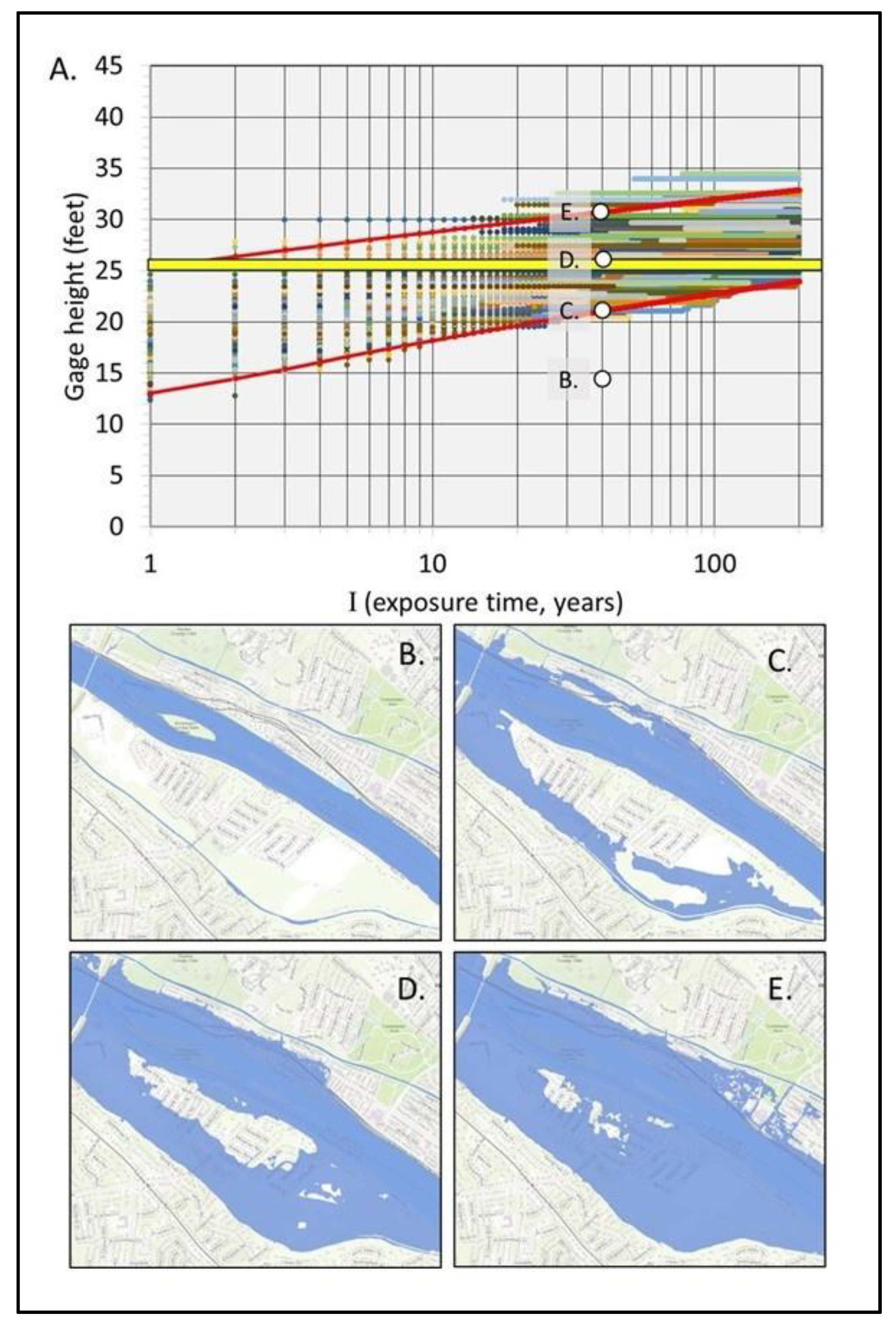

- The spread in the Q(I) ensembles indicates the range of the most severe outcomes likely to be experienced after I years; it is a visual representation of a range of outcomes that are possible. In contrast, an exceedance flow, QT, such as Q100 (Figure 4A) is a lower limit based on annual probability and has no upper limit.

- The upward sloping Q(I) ensemble reveals an often unrecognized and uncommunicated aspect of flood risk: the longer one is exposed to risk, the more likely one is to experience severe consequences. Ensembles convey a sense that time matters in mitigating flood risk. In contrast, QT is predicated on a constant annual probability, often misinterpreted to mean that risk is constant, not accumulative.

- The Q(I) ensemble (Figure 4A) shows that Q100 begins to be exceeded by a substantial proportion of simulations after as little as 10-20 years, and after 100 years of exposure most simulations exceed Q100. The perspective given by the simulations dispels the misconception that Q100 occurs once every 100 years.

- The ensemble diagram encourages possibilistic thinking. Clarke [39] gives the example of airline travel: the probability of a crash is extremely low but experience provides many examples of airline disasters and how they can occur: mid-air collision, airplane system failure, terrorism, and so forth. Similarly, Q(I) gives insight into what might be experienced in terms of future flood magnitude.

- How far in the future do I wish to consider the risk? How do age and socio-economic circumstances come into play? Young people or those committed to living or working near a flood zone might want to prepare for outcomes expected over longer exposure intervals than the elderly or those who have the economic potential to escape the flood plain.

- How much of a risk-taker am I? The bottom of the risk envelope (e.g., point C in Figure 5A) is almost always exceeded, whereas the top (e.g., point E) is rarely reached. The risk averse will want mitigation measures that keep them safe at E; the risk tolerant might take a “bet” that less costly mitigation built for C will be sufficient.

- How do different locations within a zone of possible inundation affect my understanding of risk? For example, flooding more extreme than 21 feet (Figure 5C) isolates all the properties on the island; but even at 30 feet (Figure 5E), properties on the highest ground do not flood. How does a property’s susceptibility to isolation and inundation play into an individual’s conception of risk?

4. Discussion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FloodList. 2023 [cited 2023 ]; Available from: floodlist.com. 22 June.

- Ludy, J.; Kondolf, G.M. Flood risk perception in lands “protected” by 100-year levees. Nat. Hazards 2012, 61, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, H.; Tobin, G. Efficient and effective? The 100-year flood in the communication and perception of flood risk. Environ. Hazards 2007, 7, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, P. , What can we learn from a theory of complexity? Emergence: a journal of complexity issues in organizations and management, 2000. 2(1): p. 23-33.

- Kagan, S. , Art and sustainability: Connecting patterns for a culture of complexity. 2nd emended edition ed. 2013: transcript Verlag.

- Lutz, T. ; West Chester University Adventuring into Complexity by Exploring Data: From Complicity to Sustainability. Northeast. J. Complex Syst. 2021, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, F. and P.L. Luisi, The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision. 2014: Cambridge University Press. 498.

- Dekker, S.; Cilliers, P.; Hofmeyr, J.-H. The complexity of failure: Implications of complexity theory for safety investigations. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkey, O.H. and L. Pilkey-Jarvis, Useless arithmetic: Why environmental scientists can't predict the future. 2007: Columbia University Press.

- Pilkey, O.H., R. Young, and A. Cooper, Quantitative modeling of coastal processes: A boom or a bust for society, in Rethinking the Fabric of Geology, V.R. Baker, Editor. 2013, Geological Society of America. p. 135-144.

- Baker, V. Modeling global change: Why geologists should not let "system" come between earth and science. GSA Today, 1996(May 1996): p. 8-11. 19 May.

- Baker, V. , Hydrological Understanding and Societal Action. Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 1998. 34(4): p. 819-825.

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, E. , On Complexity. Advances in Systems Theory, Complexity, and the Human Sciences, ed. A. Montuori. 2008: Hampton Press.

- Morin, E. , Restricted complexity, general complexity, in Worldviews, Science and Us: Philosophy and Complexity, C. Gershenson, Aerts, D., Edmonds, B., Editor. 2007, World Scientific Publishing. p. 5-29.

- Cilliers, P. , Critical Complexity: Collected Essays. Categories, ed. P. Roberto. 2016, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. 283.

- Woermann, M.; Cilliers, P. The ethics of complexity and the complexity of ethics. South Afr. J. Philos. 2012, 31, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B. and D. Sumara, Complexity and education: Inquiries into learning, teaching, and research. 2006: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Stewart, I. , Complicity and simplexity. Complicity: An international journal of complexity and education, 2007. 4(1): p. 105-106.

- Berman, M. , The reenchantment of the world. 1981: Cornell University Press.

- NRC, Risk Analysis and Uncertainty in Flood Damage Reduction Studies. 2000, National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences. 2000.

- Schelfaut, K.; Pannemans, B.; van der Craats, I.; Krywkow, J.; Mysiak, J.; Cools, J. Bringing flood resilience into practice: the FREEMAN project. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkholz, S.; Muro, M.; Jeffrey, P.; Smith, H. Rethinking the relationship between flood risk perception and flood management. Sci. Total. Environ. 2014, 478, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, L.J.; Krause, F.; Jones, O.; Hansen, J.G. Sustainable flood memories, informal knowledge and the development of community resilience to future flood risk. WIT Transactions on Ecology and The Environment, 2012. 159: p. 253-264.

- Henstra, D.; Minano, A.; Thistlethwaite, J. Communicating disaster risk? An evaluation of the availability and quality of flood maps. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, T. Toward a New Conceptual Framework for Teaching About Flood Risk in Introductory Geoscience Courses. J. Geosci. Educ. 2011, 59, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufty, N. , A new approach to community flood education. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 2008. 23(2): p. 4-8.

- Baker, V.R. Flood hazard science, policy, and values: A pragmatist stance. Technol. Soc. 2007, 29, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, V.R. Debates—Hypothesis testing in hydrology: Pursuing certainty versus pursuing uberty. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 1770–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, V. , Interdisciplinarity and the earth sciences: transcending limitations of the knowledge paradigm, in The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, R. Frodeman, J. Klein, and R. Pacheco, Editors. 2017, Oxford University Press. p. 88-100.

- Cilliers, P. , Boundaries, hierarchies and networks in complex systems. International Journal of Innovation Management, 2001. 5(2): p. 135-147.

- Cilliers, P. , Difference, identity and complexity. Philosophy Today, 2010. 54(1): p. 55-65.

- Bradford, R.A.; O'Sullivan, J.J.; van der Craats, I.M.; Krywkow, J.; Rotko, P.; Aaltonen, J.; Bonaiuto, M.; De Dominicis, S.; Waylen, K.; Schelfaut, K. Risk perception – issues for flood management in Europe. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 2299–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.M.; Solan, M.; Biggs, R.; McPhearson, T.; Norström, A.V.; Olsson, P.; Pereira, L.; Peterson, G.D.; Raudsepp-Hearne, C.; Biermann, F.; et al. Bright spots: seeds of a good Anthropocene. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Baldassarre, G.; Kooy, M.; Kemerink, J.S.; Brandimarte, L. Towards understanding the dynamic behaviour of floodplains as human-water systems. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 3235–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruijn, K. Resilience. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.L.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. Risk as Analysis and Risk as Feelings: Some Thoughts about Affect, Reason, Risk, and Rationality. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, M.; Jonoski, A.; Almoradie, A.; Lange, L. Collaborative decision making in sustainable flood risk management: A socio-technical approach and tools for participatory governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 55, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L. Possibilistic Thinking: A New Conceptual Tool for Thinking about Extreme Events. Soc. Res. Int. Q. 2008, 75, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piangiamore, G.L. and G. Musacchio, Participatory approach to natural hazard education for hydrological risk reduction, in Advancing culture of living with landslides, K. Sassa, M. Mikos, and Y. Yin, Editors. 2017, Springer International Publishing AG. p. 555-561.

- Nicolescu, B. , Transdisciplinarity - past, present and future, in Moving Worldviews - Reshaping Sciences, Policies, and Practices for Endogenous Sustainable Development, B. Haverkort and C. Reijntjes, Editors. 2006. p. 142-166.

- Montuori, A. , Creating Social Creativity: Integrative Transdisciplinarity and the Epistemology of Complexity, in The Palgrave Handbook of Social Creativity Research, I. Lebuda and V.P. Glaveanu, Editors. 2019. p. 407-430.

- Montuori, A. Integrative Transdisciplinarity:. Transdiscipl. J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Ross, H. Panarchy and community resilience: Sustainability science and policy implications. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 61, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J. Trust and consequences: Role of community science, perceptions, values, and environmental justice in risk communication. Risk Anal. 2022, 42, 2362–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M. A visual history of human knowledge. 2015; https://www.ted.com/talks/manuel_lima_a_visual_history_of_human_knowledge]. Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/manuel_lima_a_visual_history_of_human_knowledge.

- FEMA. History of Levees. 2020 ]; 3 page pdf document]. Available from: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/fema_history-of-levees_fact-sheet_0512.pdf. 28 August.

- Cockerill, K. , When "Solutions" Are the Problem. Water Resources IMPACT, 2022. 24(1): p. 17-18.

- Poli, R. , A note on the difference between complicated and complex social systems. Cadmus, 2013. 2(1): p. 6.

- Tobin, G.A. THE LEVEE LOVE AFFAIR: A STORMY RELATIONSHIP?1. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1995, 31, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, A.; Sanders, B.F.; Goodrich, K.A.; Feldman, D.L.; Boudreau, D.; Eguiarte, A.; Serrano, K.; Reyes, A.; Schubert, J.E.; AghaKouchak, A.; et al. Going beyond the flood insurance rate map: insights from flood hazard map co-production. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 1097–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, B.; Vorogushyn, S.; Lall, U.; Viglione, A.; Blöschl, G. Charting unknown waters—On the role of surprise in flood risk assessment and management. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 6399–6416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.R. and K.H. Hamed, Flood Frequency Analysis. New Directions in Civil Engineering, ed. W.F. Chen. 2000: CRC Press.

- Lutz, T.M. Enhancing Students' Understanding of Risk and Geologic Hazards Using a Dartboard Model. J. Geosci. Educ. 2001, 49, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeier-Klose, M.; Wagner, K. Evaluation of flood hazard maps in print and web mapping services as information tools in flood risk communication. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2009, 9, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, V. , Learning from the past. Nature, 1993. 361: p. 402-403.

- Wilhelm, B.; Cánovas, J.A.B.; Macdonald, N.; Toonen, W.H.; Baker, V.; Barriendos, M.; Benito, G.; Brauer, A.; Corella, J.P.; Denniston, R.; et al. Interpreting historical, botanical, and geological evidence to aid preparations for future floods. WIREs Water 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SERC. Search SERC. 2024 [cited 2024 3/5/2024]; Search results for "flooding"]. Available from: https://serc.carleton.edu/serc/search.html?search_text=Flooding.

- CRED, The psychology of climate change communication: a guide for scientists, journalists, educators, political aides, and the interested public, C.f.R.o.E. Decisions, Editor. N: 2009, 2009.

- Volpi, E. On return period and probability of failure in hydrology. WIREs Water 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Gutscher, H. Flooding Risks: A Comparison of Lay People's Perceptions and Expert's Assessments in Switzerland. Risk Anal. 2006, 26, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde-Hansen, J.; McEwen, L.; Holmes, A.; Jones, O. Sustainable flood memory: Remembering as resilience. Mem. Stud. 2016, 10, 384–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, N.A.J. and J.B. Peacock, Statistical Distributions: A handbook for students and practitioners. 1974, New York: Halsted Press. 130.

- USGS. Flood Inundation Mapper. [cited 2023; Version 2.5.2:[Available from: https://fim.wim.usgs.gov/fim/.

- GSA, U.S. flood risk management, GSA, Editor. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity; Dutton: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M. , Uncertain: the wisdom and wonder of being unsure. 2023: Prometheus Books. 344.

- Mujere, N. , An Innovative Water Risk Assessment Framework. Water Resources IMPACT, 2021. 23(6): p. 23-25.

- Pereira, L.M.; Karpouzoglou, T.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Olsson, P. Designing transformative spaces for sustainability in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, S.; Hauerwaas, A.; Helldorff, S.; Weisenfeld, U. Jamming sustainable futures: Assessing the potential of design thinking with the case study of a sustainability jam. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.M.; Hichert, T.; Hamann, M.; Preiser, R.; Biggs, R. Using futures methods to create transformative spaces: visions of a good Anthropocene in southern Africa. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, G. Automobility: Global Warming as Symptomatology. Sustainability 2009, 1, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woermann, M., O. Human, and R. Preiser, General complexity: A philosophical and critical perspective. Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 2018. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).