Submitted:

26 April 2024

Posted:

28 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Part 1—Quantitative Design

Participants

Questionnaire

Procedure

Part 2—Qualitative Design

Participants

Procedure

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

3. Results

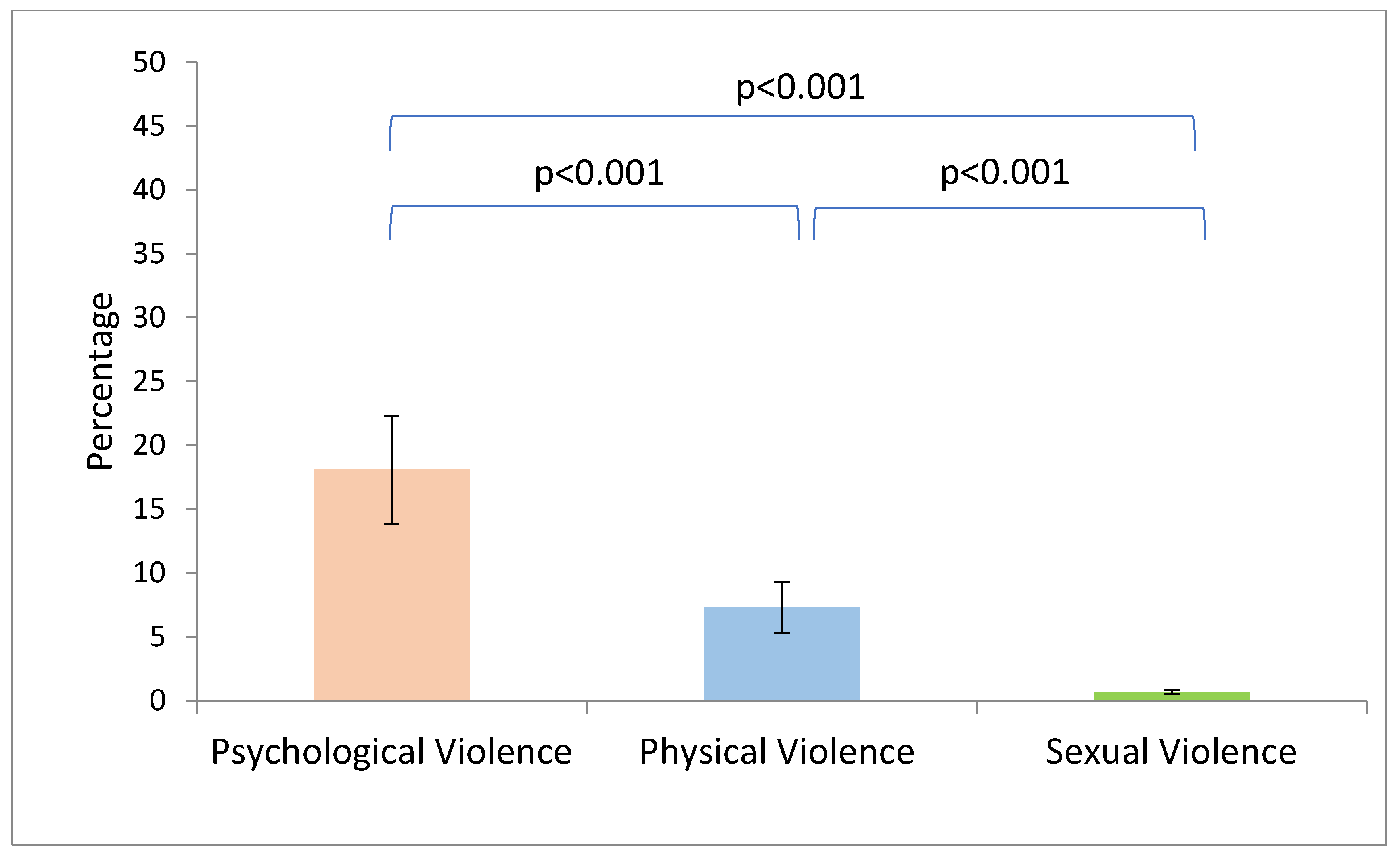

Part 1—Quantitative Design

Part 2—Qualitative Design

Theme 1. Psychological Violence

Theme 2. Verbal Violence

Theme 3. Starvation and Food Fattening

Theme 4. Non-Proportional Punishing

Theme 5. Physical Violence

Theme 6. Sexual Violence

4. Discussion

Part 1—Quantitative Design

Part 2—Qualitative Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

References

- Anney, V. N. (2014). Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: Looking at trustworthiness criteria. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 5(2), 272-281.

- Atkinson, M. (2016). Masculinity on the menu: Body Slimming and self-starvation as physical culture. Challenging myths of masculinity (pp. 81-102). Routledge.

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385-405.

- Audi, R. (1971). Intentionalistic explanations of action. Metaphilosophy, 2(3), 241-250.

- Bazeley, P. (2009). Analysing qualitative data: More than ‘identifying themes’. Malaysian Journal of Qualitative Research, 2(2), 6-22.

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Harvard University Press.

- Brackenridge, C., Fasting, K., Kirby, S., & Leahy, T. (2010). Protecting children from violence in sport; A review from industrialized countries. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

- Brackenridge, C. H., & Rhind, D. (2014). Child protection in sport: reflections on thirty years of science and activism. Social Sciences, 3(3), 326-340. [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 1(3), 185-216.

- Buecker, S., Simacek, T., Ingwersen, B., Terwiel, S., & Simonsmeier, B. A. (2021). Physical activity and subjective well-being in healthy individuals: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology Review, 15(4), 574-592.

- Charmaz, K. (2004). Premises, principles, and practices in qualitative research: Revisiting the foundations. Qualitative health research, 14(7), 976-993.

- Cho, J., & Trent, A. (2006). Validity in qualitative research revisited. Qualitative Research, 6(3), 319-340.

- Chu, T. L., & Zhang, T. (2019). The roles of coaches, peers, and parents in athletes’ basic psychological needs: A mixed-studies review. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(4), 569-588.

- Dunning, E. (2008). Violence and violence-control in long-term perspective: ‘Testing’ Elias in relation to war, genocide, crime, punishment and sport. Violence in Europe (pp. 227-249). Springer.

- Elliott, S., & Drummond, M. (2015). The (limited) impact of sport policy on parental behaviour in youth sport: a qualitative inquiry in junior Australian football. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7(4), 519-530.

- Ericsson, K. A., Prietula, M. J., & Cokely, E. T. (2007). The making of an expert. Harvard Business Review, 85(7/8), 114.

- Fejgin, N., & Hanegby, R. (2001). Gender and cultural bias in perceptions of sexual harassment in sport. International Review for the sociology of sport, 36(4), 459-478.

- Gaedicke, S., Schäfer, A., Hoffmann, B., Ohlert, J., Allroggen, M., Hartmann-Tews, I., & Rulofs, B. (2021). Sexual violence and the coach–athlete relationship: A scoping review from sport sociological and sport psychological perspectives. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 643-707.

- Gervis, M., Rhind, D., & Luzar, A. (2016). Perceptions of emotional abuse in the coach–athlete relationship in youth sport: The influence of competitive level and outcome. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 11(6), 772-779.

- Giles, S., Fletcher, D., Arnold, R., Ashfield, A., & Harrison, J. (2020). Measuring well-being in sport performers: Where are we now and how do we progress?. Sports Medicine, 50(7), 1255-1270.

- Guy & Zach, 2022.

- Hassmén, P., Kenttä, G., Hjälm, S., Lundkvist, E., & Gustafsson, H. (2019). Burnout symptoms and recovery processes in eight elite soccer coaches over 10 years. International journal of sports science & coaching, 14(4), 431-443.

- Human Rights Watch. “I was hit so many times, I can’t count.”, 2020. Available:. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/07/20/i-was-hitso-many-times-i-cant-count/abuse-child-athletes-japan [Accessed 18 Aug 2022].

- Imbusch, P. (2003). The concept of violence. International handbook of violence research (pp. 13-39). Springer.

- Jacobs, F., Smits, F., & Knoppers, A. (2017). ‘You don’t realize what you see!’: The institutional context of emotional abuse in elite youth sport. Sport in Society, 20(1), 126-143.

- Jeckell, A. S., Copenhaver, E. A., & Diamond, A. B. (2020). Hazing and bullying in athletic culture. Mental Health in the Athlete (pp. 165-179). Springer.

- Karagün, E. (2014). Self-confidence level in professional athletes; an examination of exposure to violence, branch and socio-demographic aspects. Journal of Human Sciences, 11(2), 744-753.

- Kavanagh, E., Brown, L., & Jones, I. (2017). Elite athletes’ experience of coping with emotional abuse in the coach–athlete relationship. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 29(4), 402-417.

- Kerr, G., Kidd, B., & Donnelly, P. (2020a). One step forward, two steps back: The struggle for child protection in canadian sport. Social Sciences, 9(5), 68.

- Kerr, G., Willson, E., & Stirling, A. (2020b). “It Was the Worst Time in My Life”: The effects of emotionally abusive coaching on female Canadian national team athletes. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 28(1), 81-89.

- Klotz, A. C., Swider, B. W., & Kwon, S. H. (2022). Back-translation practices in organizational research: Avoiding loss in translation. Journal of Applied Psychology.

- Lang, M., & Hartill, M. (2014). Safeguarding, child protection and abuse in sport: International perspectives in research, policy and practice. Routledge.

- LoGuercio, M. (2022). Exploring Lived Experience of Abusive Behavior among Youth Hockey Coaches. Journal of Sports and Physical Education Studies, 2(2), 01-12.

- Matthews, C. R., & Channon, A. (2017). Understanding sports violence: Revisiting foundational explorations. Sport in Society, 20(7), 751-767.

- Miles-Chan, J. L., & Isacco, L. (2021). Weight cycling practices in sport: A risk factor for later obesity?. Obesity Reviews, 22, e13188.

- Mountjoy, M., Brackenridge, C., Arrington, M., Blauwet, C., Carska-Sheppard, A., Fasting, K., Kirby, S., Leahy, T., Marks, S., Martin, K., Starr, K., Tiivas, A., & Budgett, R. (2016). International Olympic Committee consensus statement: harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1019-1029.

- Mutz, 2012.

- Nite, C., & Nauright, J. (2020). Examining institutional work that perpetuates abuse in sport organizations. Sport Management Review, 23(1), 117-129.

- Ostrowsky, M. K. (2018). Sports fans, alcohol use, and violent behavior: A sociological review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(4), 406–419. [CrossRef]

- Parent, S., & Fortier, K. (2017). Prevalence of interpersonal violence against athletes in the sport context. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16, 165-169.

- Parent, S., & Vaillancourt-Morel, M. P. (2021). Magnitude and risk factors for interpersonal violence experienced by Canadian teenagers in the sport context. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 45(6), 528-544.

- Pélissier, L., Ennequin, G., Bagot, S., Pereira, B., Lachèze, T., Duclos, M., Thivel, D., Miles-Chan, J., & Isacco, L. (2022). Lightest weight-class athletes are at higher risk of weight regain: Results from the French-Rapid Weight Loss Questionnaire. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 1-9.

- Raakman, E., Dorsch, K., & Rhind, D. (2010). The development of a typology of abusive coaching behaviours within youth sport. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 5(4), 503-515.

- Salmi, J. (1993). Violence and democratic society. Zed Books.

- Simpson, R. J., Campbell, J. P., Gleeson, M., Krüger, K., Nieman, D. C., Pyne, D. B., Turner, J. E., & Walsh, N. P. (2020). Can exercise affect immune function to increase susceptibility to infection? Exercise Immunology Review, 26, 8-22.

- Spaaij, R., & Schaillée, H. (2019). Unsanctioned aggression and violence in amateur sport: A multidisciplinary synthesis. Aggression and violent behavior, 44, 36-46.

- Spector-Mersel, G. (2010). Narrative research: Time for a paradigm. Narrative inquiry, 20(1), 204-224.

- State Comptroller Report. (2018-2019). Applying the law. Retrieved on January 9th, 2023. Available online: https://www.mevaker.gov.il/sites/DigitalLibrary/Pages/Reports/3285-2.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1.

- Stirling, A. E., Bridges, E. J., Cruz, E. L., & Mountjoy, M. L. (2011). Canadian Academy of Sport and Exercise Medicine position paper: Abuse, harassment, and bullying in sport. Clinical journal of sport medicine, 21(5), 385-391.

- Stirling, A. E., & Kerr, G. (2013). The perceived effects of elite athletes’ experiences of emotional abuse in the coach-athlete relationship. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 87-100.

- Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Alink L. R. A., Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review, 24(1), 37-50.

- The Law for preventing sexual harassment. (1998). Retrieved on January 9th, 2023. Available online: https://www.nevo.co.il/law_html/law00/72507.htm.

- Vazou, S., Ntoumanis, N., & Duda, J. L. (2006). Predicting young athletes’ motivational indices as a function of their perceptions of the coach-and peer-created climate. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7(2), 215-233.

- Vertommen, T., Kampen, J., Schipper-van Veldhoven, N., Uzieblo, K., & Van Den Eede, F. (2018). Severe interpersonal violence against children in sport: Associated mental health problems and quality of life in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 459-468.

- WHO. (1999). Report of the consultation on child abuse prevention (No. WHO/HSC/PVI/99.1).

| Items | 1 Never |

2 Rarely (1-2 times) |

3 Some-times (3-10 times) |

4 Very often (>10 times) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shook, pushed, grabbed, or threw you | 84.5 | 11.2 | 2.3 | 2 |

| 2 | Threw an object directly at you | 88.2 | 8.1 | 3.0 | 0.7 |

| 3 | Hit you with the hand (for example, slaps) | 92.0 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 0.9 |

| 4 | Punched or kicked you | 97.0 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 5 | Hit you with an object (for example, sports equipment) | 91.1 | 6.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| 6 | Tried to strangle you | 98.0 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.2 |

| 7 | Hit or threw objects that were not aimed directly at you (e.g., water bottles, pens) | 78.0 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 2.0 |

| 8 | Forced you/instructed you to injure an opposing player | 90.5 | 6.4 | 2.0 | 1.1 |

| 9 | Forced you/instructed you to humiliate or mock an opponent | 92.0 | 6.1 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| 10 | Forced you/instructed you to threaten or hurt an opponent | 92.0 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| 11 | Allowed you to injure an opposing player (with a punch, sports equipment, etc.) in a competition, without intervening | 93.6 | 5.2 | 1.2 | / |

| 12 | Allowed you to humiliate or mock an opponent in a competition, without interfering | 90.7 | 6.1 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

| 13 | Allowed you to threaten or hurt an opponent in a competition without intervening | 91.8 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 0.7 |

| 14 | Threatened to leave/ abandon you | 88.9 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 1.3 |

| 15 | Threatened to harm you | 91.4 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 0.7 |

| 16 | Threatened to harm someone or something you love | 95.2 | 3.4 | 1.4 | / |

| 17 | Yelled at you and insulted you, humiliated you, and mocked you | 59.5 |

23.0 | 11.4 | 6.1 |

| 18 | Criticized you excessively (e.g., about your performance or your attitude) | 50.2 | 23.6 | 18.9 | 7.3 |

| 19 | Expelled or suspended you | 72.5 | 20.9 | 4.6 | 2.0 |

| 20 | Locked you in a closed room or tried to limit your freedom of movement (e.g., locking you in the locker room, tying you up) | 97.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | / |

| 21 | Asked you to limit or reduce your social connections (with friends, romantic partners, or family member) to enable you to invest more of yourself in your sports | 77.0 | 15.9 | 5.9 | 1.1 |

| 22 | Ignored you or treated you with indifference (e.g., refused to talk to you, ignored your existence) | 66.6 | 20.5 | 9.1 | 3.9 |

| 23 | Forced you/instructed you to do extra high-intensity and excessive training until you were exhausted | 72.5 | 15.2 | 8.9 | 3.4 |

| 24 | Forced you/instructed you to exercise while injured despite having a medical opinion to the contrary | 77.0 | 13.0 | 6.6 | 3.4 |

| 25 | Forced you/instructed you to perform movements or technical actions that are more difficult than you are capable of (physically or psychologically) that had or could have had negative consequences on your health and safety | 78.2 | 16.4 | 3.4 | 2.0 |

| 26 | Asked you to use prohibited substances to reach the desired weight for the sport (fasting, vomiting, pills) | 96.8 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| 27 | Asked you to use prohibited substances to improve performance (steroids, hormones) | 97.1 | 1.1 | 0.2 | |

| 28 | Knew that you had used prohibited substances to reach the desired weight for the industry | 98.2 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| 29 | Knew that you had used prohibited substances to improve performance | 98.6 | 0.5 | 0.9 | |

| 30 | Asked you to stop going to school or suspend your studies in order to devote yourself to sports | 88.2 | 7.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 31 | Made rude, insulting comments that made you uncomfortable about your sex life, your private life, or your physical appearance (for example, comments about you or your partner’s intimate body parts) | 87.3 | 8.6 | 2.7 | 1.4 |

| 32 | Behaved sexually in a way that made you feel uncomfortable (for example, rubbing you, staring at you, undressing you with their eyes, whistling at you, and massaging you) | 88.2 | 8.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 33 | Watched you or force you to perform a sexual act (touching yourself, themselves, or others) | 94.3 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| 34 | Photographed you while you were having sexual activity (touching yourself, themselves, or others) | 97.7 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Variable | Standardized β (CI) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - 0.05 (-0.15-0.04) | -1.08 | 0.27 |

| Gender | 0.08 (-0.25-3.22) | 1.67 | 0.94 |

| Sport type | - 0.13 (-0.75-0.56) | -0.27 | 0.78 |

| Individual/team | 0.23 (-1.30-2.16) | 0.48 | 0.62 |

| Age of retirement | 0.12 (0.01-0.257) | 2.15 | 0.032* |

| Retirement: yes/no | -0.06 (-2.97-0.59) | -1.30 | 0.19 |

| Achievements | -0.01 (-1.16-0.92) | -0.22 | 0.81 |

| Years of practice | 0.09 (-0.003-0.29) | 1.926 | 0.055 |

| Number of coaches | 0.14 (0.108-0.496) | 3.056 | 0.002* |

| Occupation | 0.031 (-0.787-1.575) | 0.655 | 0.513 |

| Residence | -0.012( -1.717-1.342) | -0.241 | 0.810 |

| Zone | 0.029 (-0.386-0.716) | 0.0589 | 0.0556 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).