Submitted:

26 April 2024

Posted:

28 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Experimental Design

Aims and Hypotheses

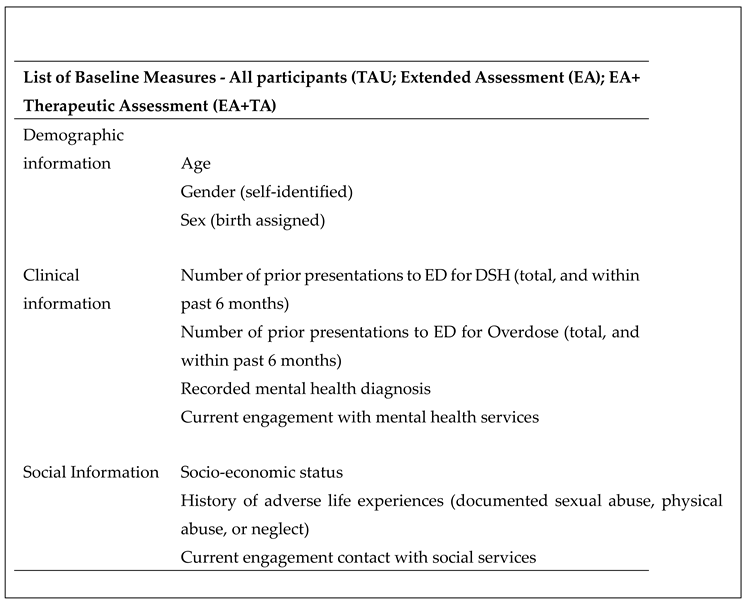

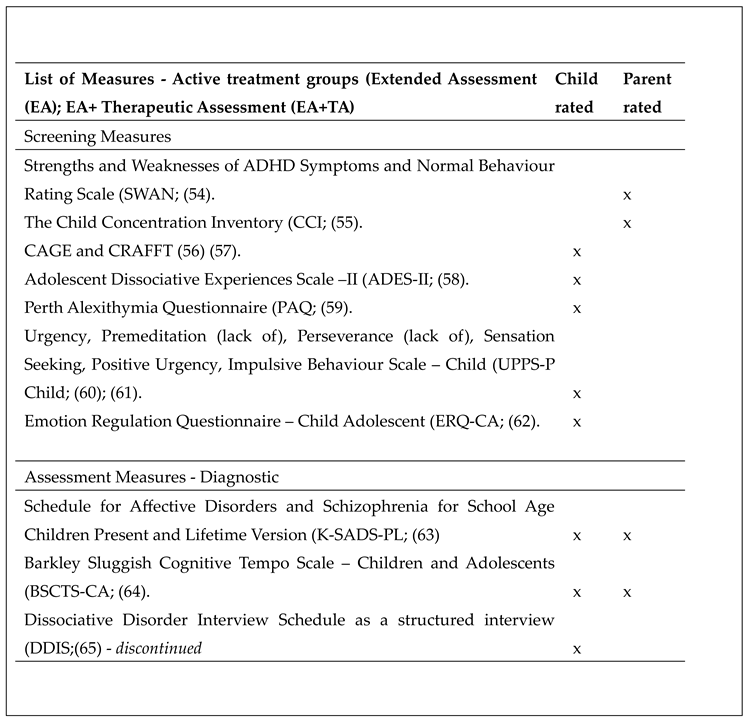

Materials and Methods

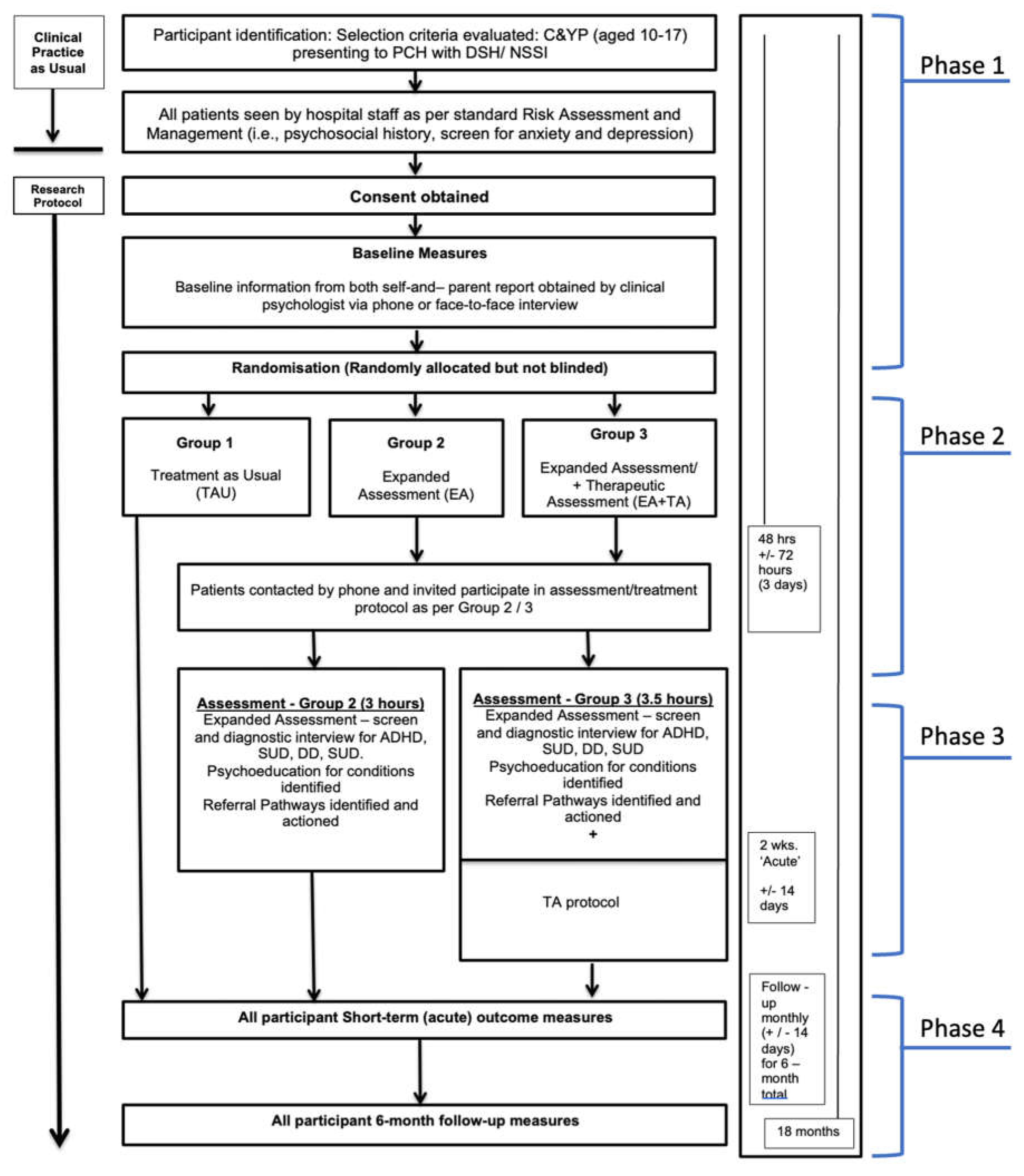

Trial Design and Conceptual Framework

Study Setting

Eligibility Criteria

Sample Size

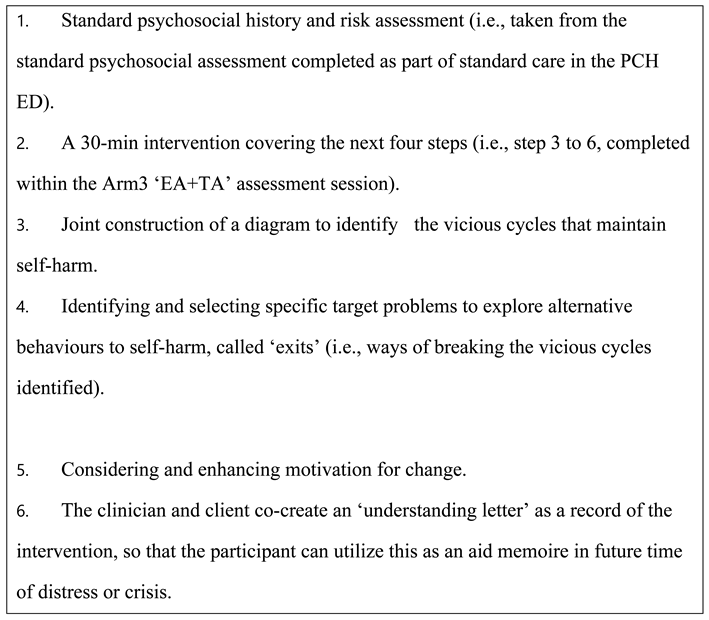

Detailed Procedure

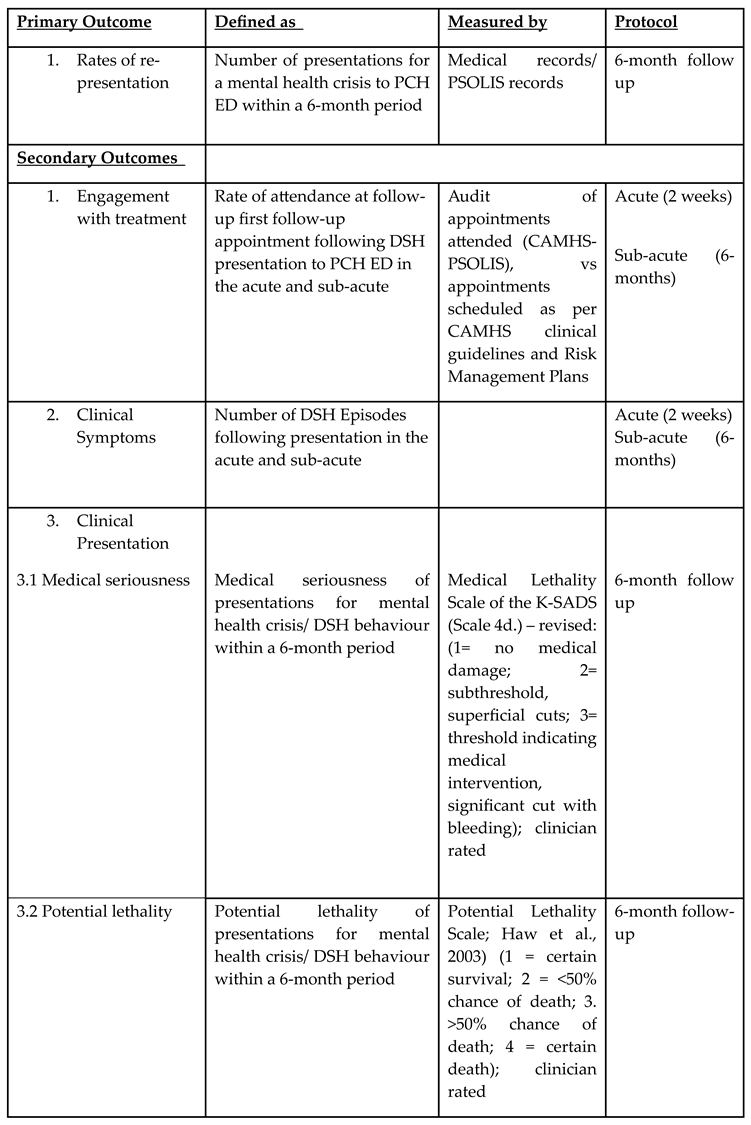

Data Analysis

Addressing and Mitigating Information Bias

Ethics and Dissemination

Expected Results

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

| 1 | *(ADHD med) is bracketed, as it is not given to all participants in Arm 2 and 3, but given only to those with pre-existing ADHD diagnosis, or those who are diagnosed with ADHD de novo during EXPAAND Phase 2 and consent to taking ADHD medications. |

References

- Hawton K: Saunders KE, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet. 2012 Jun 1;379(9834):2373–82. [CrossRef]

- Torok M, Burnett AC, McGillivray L, et al. Self-harm in 5-to-24 year olds: Retrospective Examination of Hospital Presentations to emergency departments in New South Wales, Australia, 2012 to 2020. PLOS ONE. 2023 Aug 10;18(8). [CrossRef]

- Neufeld SAS. The burden of young people’s mental health conditions in Europe: No cause for complacency. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2022 May;16:100364. [CrossRef]

- Quinlivan L, Cooper J, Meehan D, et al. Predictive accuracy of risk scales following self-harm: multicentre, prospective cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(6):429-436. [CrossRef]

- National Mental Health Commission. Monitoring mental health and suicide prevention reform: National Report 2019. Sydney: NMHC; 2019.

- Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, Esposito J. US Pediatric Emergency Department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2021 Apr 30;4(4). [CrossRef]

- Holland KM, Jones C, Vivolo-Kantor AM, et al. Trends in US Emergency Department Visits for Mental Health, Overdose, and Violence Outcomes Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(4):372-379. [CrossRef]

- Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, et al. Emergency Department Visits for Suspected Suicide Attempts Among Persons Aged 12-25 Years Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, January 2019-May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(24):888-894. Published 2021 Jun 18. [CrossRef]

- Ombudsmun WA. Volume 1: Ombudsman’s Foreword and Executive Summary. Western Australia; 2020.

- Sara G, Wu J, Uesi J, et al. Growth in emergency department self-harm or suicidal ideation presentations in young people: Comparing trends before and since the COVID-19 first wave in New South Wales, Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2023;57(1):58-68. [CrossRef]

- Shankar LG, Habich M, Rosenman M, et al. Mental Health Emergency Department Visits by Children Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(7):1127-1132. [CrossRef]

- Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, et al.Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142-1150. [CrossRef]

- Ougrin D, Wong BH, Vaezinejad M, et al. Pandemic-related emergency psychiatric presentations for self-harm of children and adolescents in 10 countries (PREP-kids): a retrospective international cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31(7):1-13. [CrossRef]

- Woo HG, Park S, Yon H, et al. National Trends in Sadness, Suicidality, and COVID-19 Pandemic-Related Risk Factors Among South Korean Adolescents From 2005 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2314838. Published 2023 May 1. [CrossRef]

- Joiner TE Jr, Brown JS, Wingate LR. The psychology and neurobiology of suicidal behavior. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:287-314. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson P, Goodyer I. Non-suicidal self-injury. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(2):103-108. [CrossRef]

- Hawton K, Bale L, Brand F, et al. Mortality in children and adolescents following presentation to hospital after non-fatal self-harm in the Multicentre Study of Self-harm: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(2):111-120. [CrossRef]

- Bennardi M, McMahon E, Corcoran P, et al. Risk of repeated self-harm and associated factors in children, adolescents and young adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):421. Published 2016 Nov 24. [CrossRef]

- Summers P, O'Loughlin R, O'Donnell S, et al. Repeated presentation of children and adolescents to the emergency department following self-harm: A retrospective audit of hospital data. Emerg Med Australas. 2020;32(2):320-326. [CrossRef]

- Hawton K, Bergen H, Kapur N, et al. Repetition of self-harm and suicide following self-harm in children and adolescents: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(12):1212-1219. [CrossRef]

- Geulayov G, Casey D, Bale L, et al. Self-harm in children 12 years and younger: characteristics and outcomes based on the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(1):139-148. [CrossRef]

- Plener PL, Schumacher TS, Munz LM, Groschwitz RC. The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: a systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2015;2:2. Published 2015 Jan 30. [CrossRef]

- Taylor PJ, Jomar K, Dhingra K, et al. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury [published correction appears in J Affect Disord. 2019 Dec 1;259:440]. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:759-769. [CrossRef]

- Eskander N, Vadukapuram R, Zahid S, et al. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Suicidal Behaviors in American Adolescents: Analysis of 159,500 Psychiatric Hospitalizations. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e8017. Published 2020 May 7. [CrossRef]

- Parker, G. & Ricciardi, T. (2019). The Risk of Suicide and Self-Harm in Adolescents Is Influenced by the “Type” of Mood Disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 207 (1), 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Gili M, Castellví P, Vives M, et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for suicidal behavior in young people: A meta-analysis and systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:152-162. [CrossRef]

- Krug I, Arroyo MD, Giles S, et al. A new integrative model for the co-occurrence of non-suicidal self-injury behaviours and eating disorder symptoms. J Eat Disord. 2021;9(1):153. Published 2021 Nov 22. [CrossRef]

- Preece DA, Mehta A, Becerra R, et al. Why is alexithymia a risk factor for affective disorder symptoms? The role of emotion regulation. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:337-341. [CrossRef]

- Norman H, Oskis A, Marzano L, Coulson M. The relationship between self-harm and alexithymia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Psychol. 2020;61(6):855-876. [CrossRef]

- Hoyos C, Mancini V, Furlong Y, et al. The role of dissociation and abuse among adolescents who self-harm. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019;53(10):989-999. [CrossRef]

- Becker SP, Leopold DR, Burns GL, et al. The Internal, External, and Diagnostic Validity of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo: A Meta-Analysis and Critical Review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(3):163-178. [CrossRef]

- Preece, D. A., & Gross, J. J. (2023). Conceptualizing alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences, 215, [112375]. [CrossRef]

- Preece DA, Mehta A, Petrova K, et al. Alexithymia and emotion regulation. J Affect Disord. 2023;324:232-238. [CrossRef]

- Allely CS. The association of ADHD symptoms to self-harm behaviours: a systematic PRISMA review. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:133. Published 2014 May 7. [CrossRef]

- Septier M, Stordeur C, Zhang J, et al. Association between suicidal spectrum behaviors and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;103:109-118. [CrossRef]

- Liu WJ, Mao HJ, Hu LL, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication and risk of suicide attempt: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2020 Nov;29(11):1364-72.

- Chen W, Taylor E. Resilience and self-control impairment. Handbook of resilience in children: Springer; 2023. p. 175-211.

- Lieslehto J, Tiihonen J, Lähteenvuo M, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Pharmacotherapies for the Risk of Attempted or Completed Suicide Among Persons With Borderline Personality Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(6):e2317130. Published 2023 Jun 1. [CrossRef]

- Gillies D, Christou MA, Dixon AC, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Self-Harm in Adolescents: Meta-Analyses of Community-Based Studies 1990-2015. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(10):733-741. [CrossRef]

- Borschmann R, Kinner SA. Responding to the rising prevalence of self-harm. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):548-549. [CrossRef]

- Zetterqvist M, Jonsson LS, Landberg Å, Svedin CG. A potential increase in adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury during covid-19: A comparison of data from three different time points during 2011 - 2021. Psychiatry Res. 2021;305:114208. [CrossRef]

- Ougrin D, Zundel T, Ng AV. Self-harm in young people: A therapeutic assessment manual: CRC Press; 2009.

- Finn SE, Tonsager ME. How therapeutic assessment became humanistic. The Humanistic Psychologist. 2002;30(1-2):10-22. [CrossRef]

- Finn SE, Fischer CT, Handler L. Collaborative/therapeutic assessment: Basic concepts, history, and research. Collaborative/therapeutic assessment: A casebook and guide. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2012. p. 1-24.

- Finn B. Exploring interactions between motivation and cognition to better shape self-regulated learning. Journal of Applied research in Memory and Cognition. 2020;9(4):461-7. [CrossRef]

- Hawton K, Witt KG, Taylor Salisbury TL, et al. Interventions for self-harm in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(12):CD012013. Published 2015 Dec 21. [CrossRef]

- Ougrin D, Zundel T, Ng A, et al. Trial of Therapeutic Assessment in London: randomised controlled trial of Therapeutic Assessment versus standard psychosocial assessment in adolescents presenting with self-harm. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(2):148-153. [CrossRef]

- Ougrin D, Boege I, Stahl D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of therapeutic assessment versus usual assessment in adolescents with self-harm: 2-year follow-up. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(10):772-776. [CrossRef]

- Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 Statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015;38(6):506-514.

- Gerhand S, Saville CWN. ADHD prevalence in the psychiatric population. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2022;26(2):165-177. [CrossRef]

- Adamis D, Flynn C, Wrigley M, et al. ADHD in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence Studies in Outpatient Psychiatric Clinics. J Atten Disord. 2022;26(12):1523-1534. [CrossRef]

- Manor I, Gutnik I, Ben-Dor DH, et al. Possible association between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and attempted suicide in adolescents - a pilot study. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(3):146-150. [CrossRef]

- Saghaei M, Saghaei S. Implementation of an open-source customizable minimization program for allocation of patients to parallel groups in clinical trials. J Biomed Sci Eng. 2011;4(11):734-9. [CrossRef]

- Swanson J, Deutsch C, Cantwell D, et al. Genes and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2001;1(3):207-16. [CrossRef]

- Becker SP, Luebbe AM, Joyce AM. Child Concentration Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, et al. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: a comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(1):67-73. [CrossRef]

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(6):607-614. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong JG, Putnam FW, Carlson EB, et al. Development and validation of a measure of adolescent dissociation: the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185(8):491-497. [CrossRef]

- Preece D, Becerra R, Robinson K, et al. The psychometric assessment of alexithymia: Development and validation of the Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences. 2018;132:32-44. [CrossRef]

- Zapolski TC, Stairs AM, Settles RF, et al. The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment. 2010;17(1):116-125. [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, S.P. and Lynam, D.R. (2001) The Five Factor Model and Impulsivity: Using a Structural Model of Personality to Understand Impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 669-689. [CrossRef]

- Gullone E, Taffe J. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (ERQ-CA): a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(2):409-417. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980-988. [CrossRef]

- Barkley RA. Barkley sluggish cognitive tempo scale--children and adolescents (BSCTS-CA): Guilford Publications; 2018.

- Ross CA, Duffy CMM, Ellason JW, et al. Prevalence, Reliability and Validity of Dissociative Disorders in an Inpatient Setting, Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 3:1, 7-17. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).